Prison stories are basically their own genre, what with the dangerous, claustrophobic environment, the parallel rules of life in a world of outlaws, full of both comradery and suspicion, and the occasional trope of elaborate escape plots (which are kind of reverse-heist tales). For many, I suspect, there is a thrill that comes from accessing a place that’s designed to be invisible to most of society, but these stories can also be a way to reflect and comment on the most unfair and dehumanizing features of the whole justice system.

Detective Comics #644

Detective Comics #644

This genre is able to accommodate much crosspollination. In cinema, masterpieces include overlaps with film noir (Jules Dassin’s Brute Force, Joseph Losey’s The Criminal), social realism (Héctor Babenco’s Carandiru, Steve McQueen’s Hunger, Jacques Audiard’s A Prophet), and WWII-themed black comedies (Billy Wilder’s Stalag 17, Peter Lord’s and Nick Park’s Chicken Run).

In comics, prison yarns range from the gritty Tyler Cross: Angola to the hilarious Kaijumax series (which, as the title suggests, is about a maximum-security prison for kaiju monsters!), not to mention the countless times we got to follow the Punisher behind bars. Brian Azzarello wrote strong prison arcs in both Hellblazer and 100 Bullets. Steve Gerber turned incarceration into a brilliant metaphor for high school life in Hard Time. Kelly Sue DeConnick did an awesome sci-fi riff on women-in-prison exploitation, with Bitch Planet. John Ostrander came up with a typically surreal take in Grimjack #73-74, where inmates served multiple life sentences as they reincarnated and were incarcerated for crimes committed in past lives.

Gotham City has its own prison, the Alcatraz-inspired Blackgate Penitentiary, which is predictably violent and overcrowded. Even before it was properly identified as Blackgate, there were a couple of remarkable tales set there. One of them was ‘When the Inmates Run the Madhouse!’ (Detective Comics #489, cover-dated April 1980), in which Commissioner Gordon single-handedly squashed a riot. The other, ‘Blind Justice… Blind Fear!’ (Detective Comics #421, March 1972), is somehow even more hardboiled… Written and illustrated by the underrated Frank Robbins, it deals with a failed prison break that results in a hostage situation involving five guards and two inmates. Batman breaks into prison to rescue one of the hostages, Carlton Quayle, a former assistant D.A. who can help expose the city’s corruption at the highest level. Inside, however, the Dark Knight finds himself wrapped in racial tension:

Detective Comics #421

Detective Comics #421

It was only in the 1990s that Blackgate became more than just a generic prison. ‘The Hungry Grass!’ (Detective Comics #629) gave it a name and a backstory: built in the late nineteen hundreds, condemned by Amnesty International, ‘its history reads like an Edgar Allan Poe novel.’ The Ventriloquist often ended up there, despite receiving instructions from a wooden puppet, which you’d think would make him more fit for Arkham Asylum (don’t get me wrong, I love this choice: it conveys the notion that *everyone* in Gotham is at least a bit off anyway, so apparently having a killer dummy as an alter ego isn’t enough for the courts to consider you criminally insane). The hardass warden, Victor Zerhard, became a recurring character.

This is a corner of Gotham City I’m quite fond of. It gives us a continuation of previous stories, after Batman and/or Robin caught the crooks, thus creating a more fully fleshed-out world where the villains exist beyond their encounters with the Dynamic Duo – and where minor foes (and henchmen) even get to interact with each other, thus further interlinking different stories. Moreover, there is something comically sadistic about taking colorful criminals and shoving them in a drab prison environment, where their idiosyncrasies suddenly look especially pathetic.

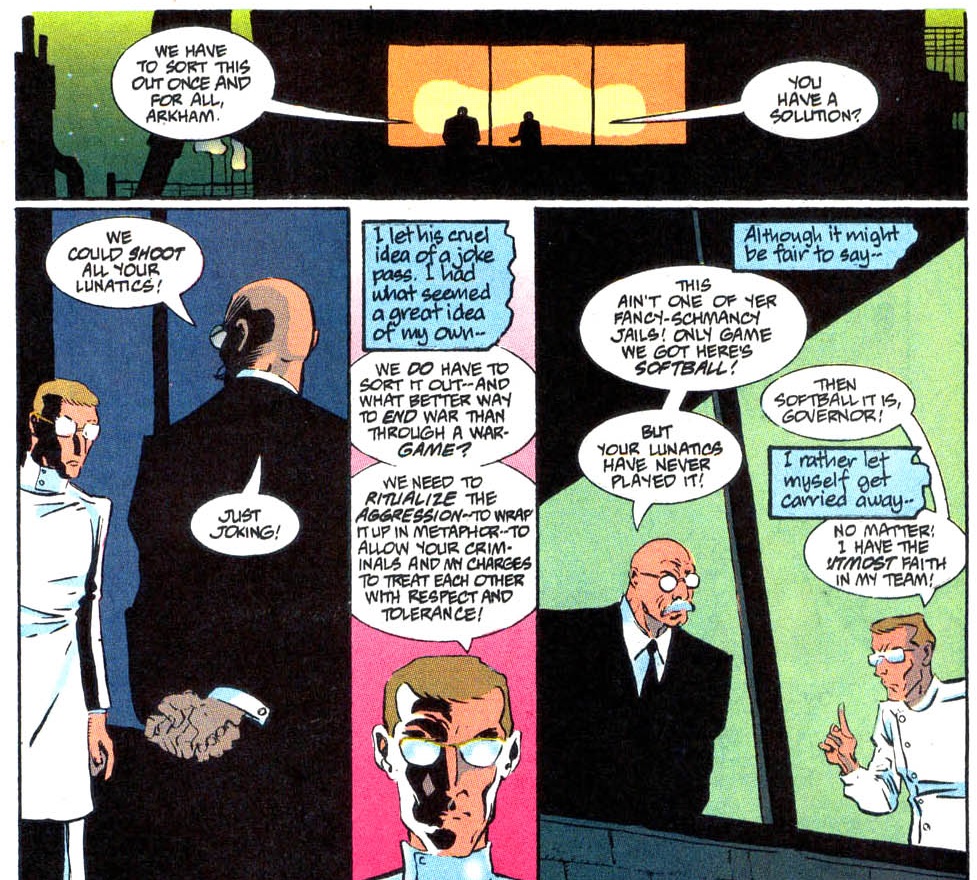

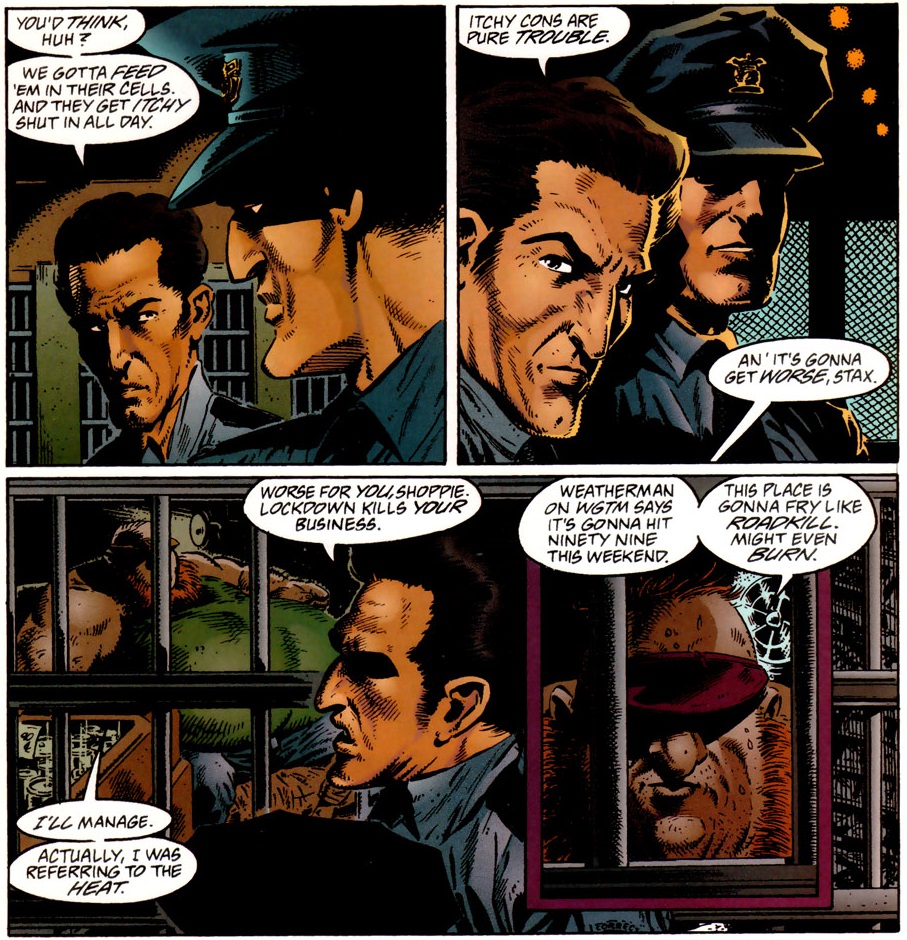

The first story to make full use of this setting’s black comedy potential was ‘Madmen Across the Water’ (which first came out in the anthology series Showcase ’94 #3-4 and it has been collected in the book Tales of the Batman: Tim Sale). In this sidestory to the Knightfall saga going on in the main titles, a handful of rogues from Arkham are temporarily transferred to Blackgate island after the asylum’s destruction, including Poison Ivy, Two-Face, the Scarecrow, the Riddler, Amygdala, and the serial killer Cornelius Stirk, as well as a couple of kooky new additions: the suicidal Jim Paul Sarter and the delusional Doctor Faustus (‘He claims to be immortal, though our records show him to be 43’). Needless to say, the rogues’ caustic behavior doesn’t sit well with Warden Zerhardt, nor do they get along with the regular Blackgate inmates.

Showcase ’94 #3

Showcase ’94 #3

‘Madmen across the Water’ is such a nice example of how amusingly twisted things can get in the world of Batman comics. The wonderful team of writer Alan Grant and artist Tim Sale keep the gags coming, culminating in a bizarre game of softball. At one point, someone compliments Cornelius Stirk on his pitching skills, to which he replies: ‘They’re well-exercised, those muscles. That’s my stabbing arm, you know!’ (Soon afterwards, Grant wrote a more straightforward action thriller set in Blackgate, in Shadow of the Bat #33.)

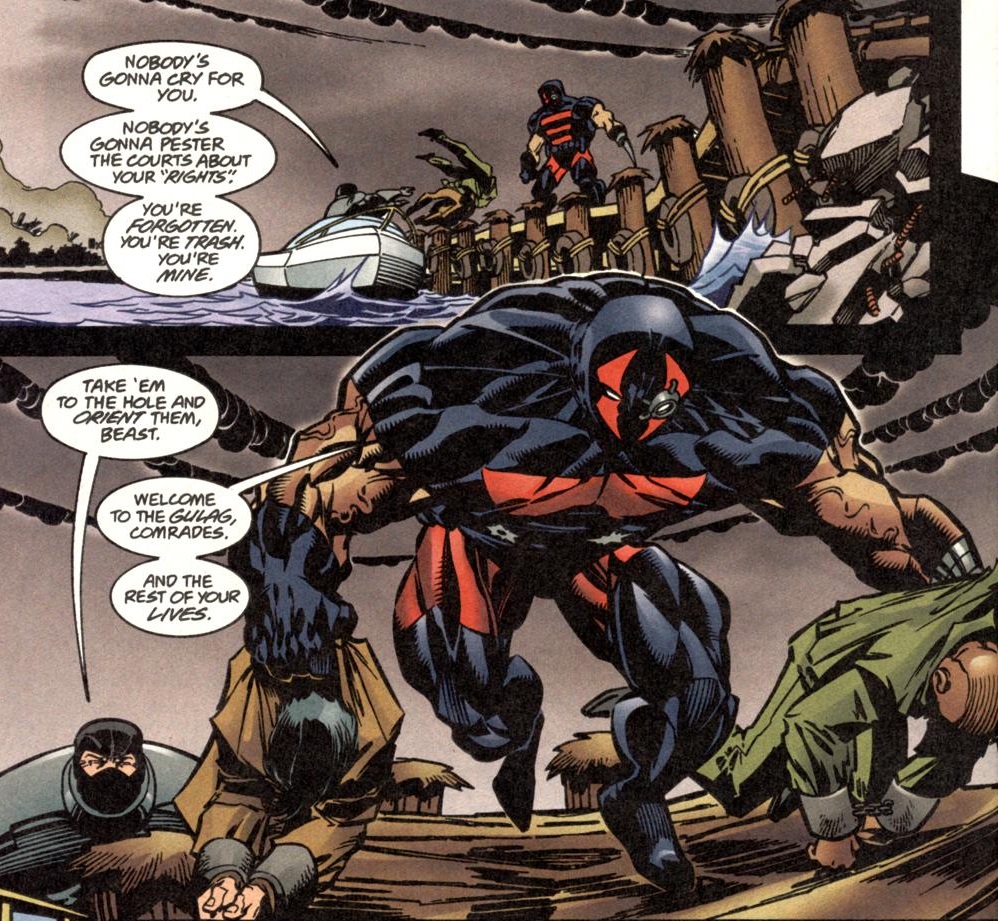

One character whose history is intrinsically tied with prison fiction is Bane. Indeed, after having crafted one hell of a prison yarn in the original Vengeance of Bane one-shot – about Bane’s childhood in Santa Prisca’s prison of Peña Duro – Chuck Dixon and Graham Nolan did a cool sequel about the character’s life in Blackgate (following his defeat at the hands of Batman in the Knightfall story arc).

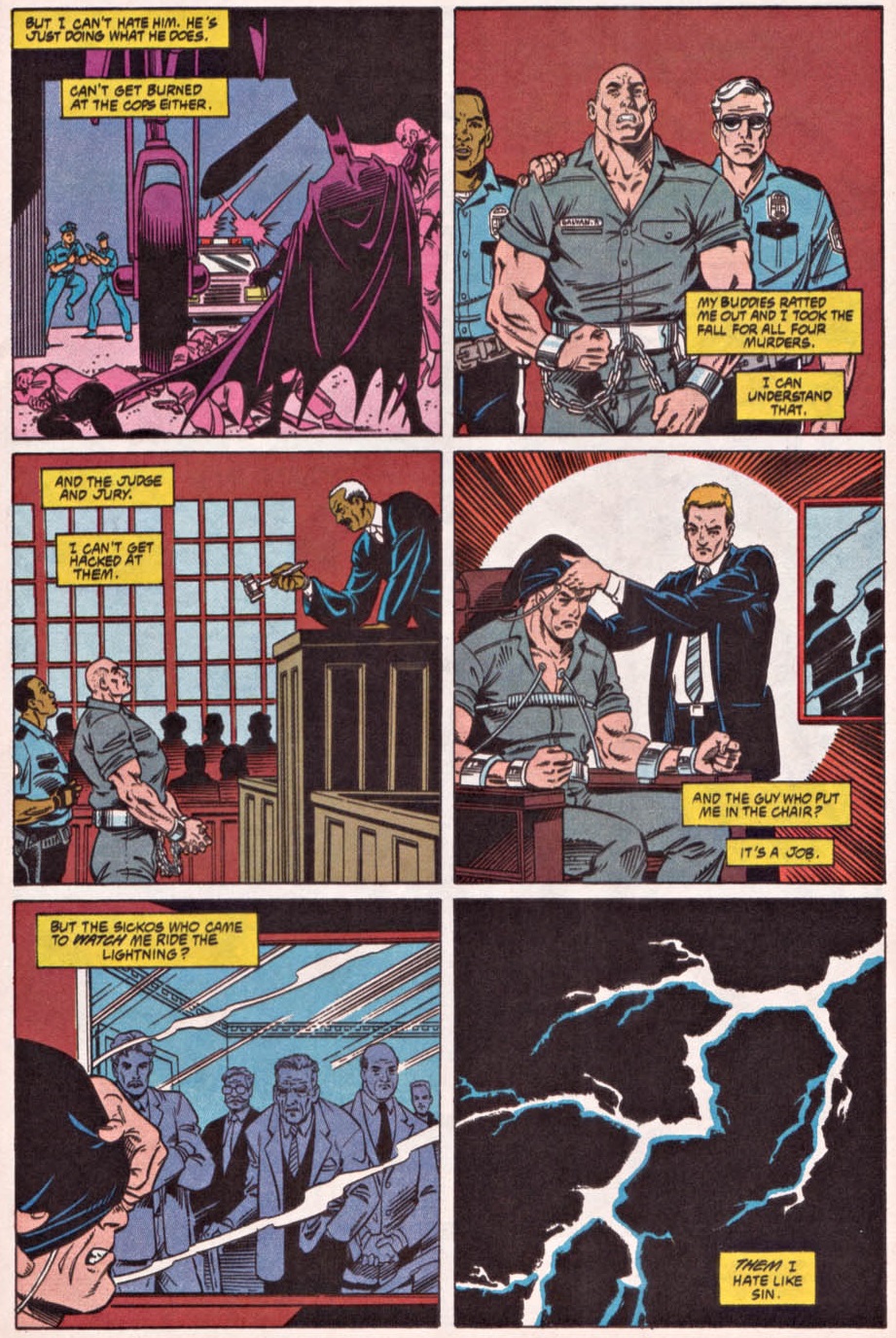

Vengeance of Bane II: The Redemption

Vengeance of Bane II: The Redemption

In 1995’s Vengeance of Bane II: The Redemption, this villain – who is much more interesting in Dixon’s books than in the movies (he’s a polyglot chess master genius with eidetic memory as well as a physical powerhouse) – has to negotiate his place among inmates such as the Ratcatcher and the KGBeast while still struggling with a cold turkey detox from his addiction to the drug known as ‘venom.’

In a neat bit of fan-pleasing continuity, Dixon brings in some of the eccentric characters he had previously introduced in Batman comics, including the inept psychiatrist Simpson Flanders and the electricity-powered criminal Elmo Galvan (whose origin you can see in the first scan of this post). Yet the script – and Nolan’s art, inked by Eduardo Barreto and colored by Adrienne Roy – treats the story like a straight-up crime drama, even if discretely winking at the audience, thus living up to that longstanding comics tradition of turning harsh sociopolitical issues into tasteless entertainment (which is, after all, the whole formula behind the Caped Crusader’s war on crime). The result at times feels like a quirkier version of Don Siegel’s Escape from Alcatraz – there is even a similar instance of mouse-based communication!

Dixon then took the genre mash-up even further in the one-shot Blackgate: Hatred’s Home.

Blackgate: Hatred’s Home

Blackgate: Hatred’s Home

This one is hands-down my favorite Blackgate tale. Batman sets the grisly tone early on by claiming that in a lot of ways the inmates on Blackgate Island are as dangerous as the ones in Arkham Asylum: ‘There’re more of them and they’re not crippled by dementia.’ The high concept here is that Arthur ‘Cluemaster’ Brown and Garfield ‘Firefly’ Lynns are preparing a major breakout, so the Caped Crusader infiltrates the prison in order to foil their plans. The thing is that we don’t know who Batman is posing as, so the story is essentially structured like a mystery full of red herrings.

That said, most of the fun comes from watching a bunch of Z-list villains dealing with prison life and backstabbing each other at every turn. The issue is populated not only by the usual inmates (Ratcatcher and the KGBeast show up again), but also by every lame villain who ever showed up in a Dixon comic, from Liam ‘Gunhawk’ Hawkleigh (of Detective Comics #674-675) to Phillip ‘Dragoncat’ Parsons (of Robin #21-22), from Actuary (of Detective Comics #683-684) to Steeljacket (of Robin #13), from the Trigger Twins (of Detective Comics #667-669) to Cap’n Fear (of Detective Comics #687-688). The great penciller Joe Staton, inked by James A. Hodgkins, is then tasked with helping readers identify these rogues while out of their distinctive costumes – a task made even more challenging by the fact that colorist John Kalisz drenches the pages in oppressive shadows.

Indeed, although Blackgate: Hatred’s Home is technically a standalone story (with a few references to Vengeance of Bane II), you’ll get more out of it the more familiar you are with Batman comics from the early-to-mid-nineties. Dixon sure liked his cross-continuity – and, to be fair, he was damn good at it! In fact, he continued to use Blackgate in several of his other projects…

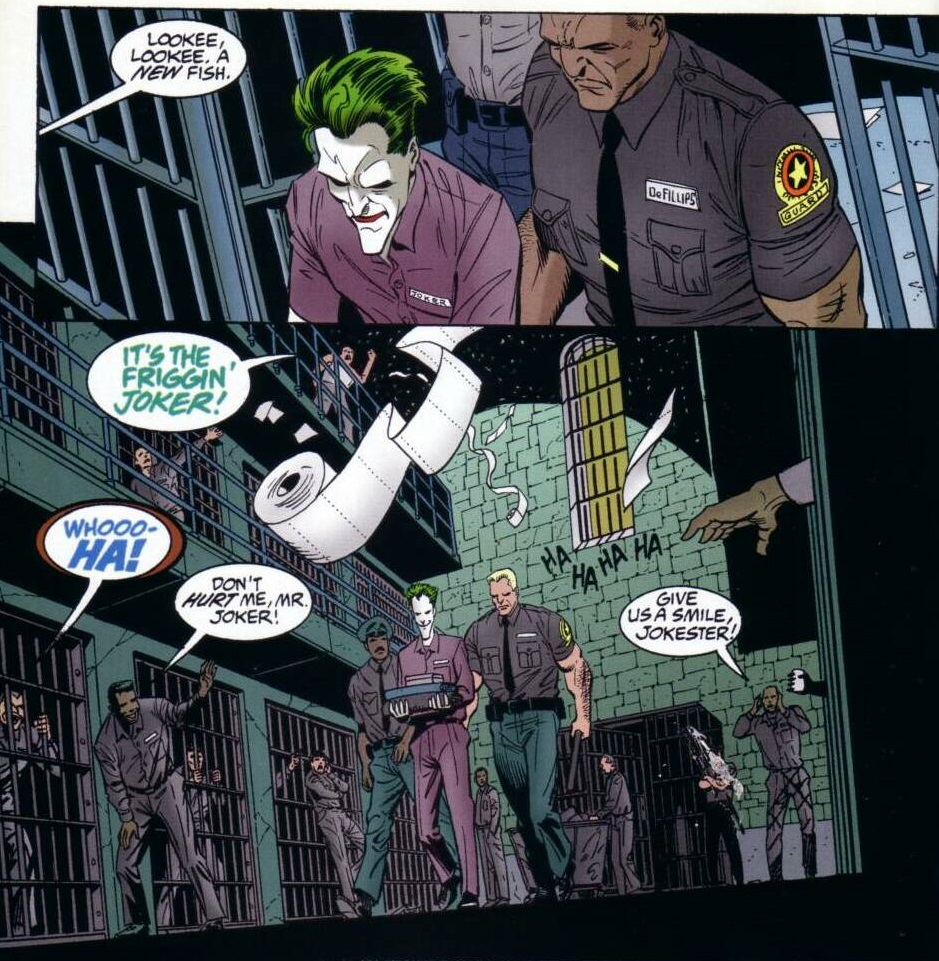

Joker: The Devil’s Advocate

Joker: The Devil’s Advocate

When it came to the Cataclysm crossover, however, it was Doug Moench who got to pen the Blackgate tie-in, for some reason. In this downbeat event, Gotham City was devastated by an earthquake and the special Blackgate: Isle of Men showed the impact on the prison. The result is as chaotic as you’d expect – besides the quake, the staff end up facing a tsunami, a mutiny, and a prison break! (The prisoners who manage to escape go on to feature in the action-packed one-shot Huntress/Spoiler: Blunt Trauma.)

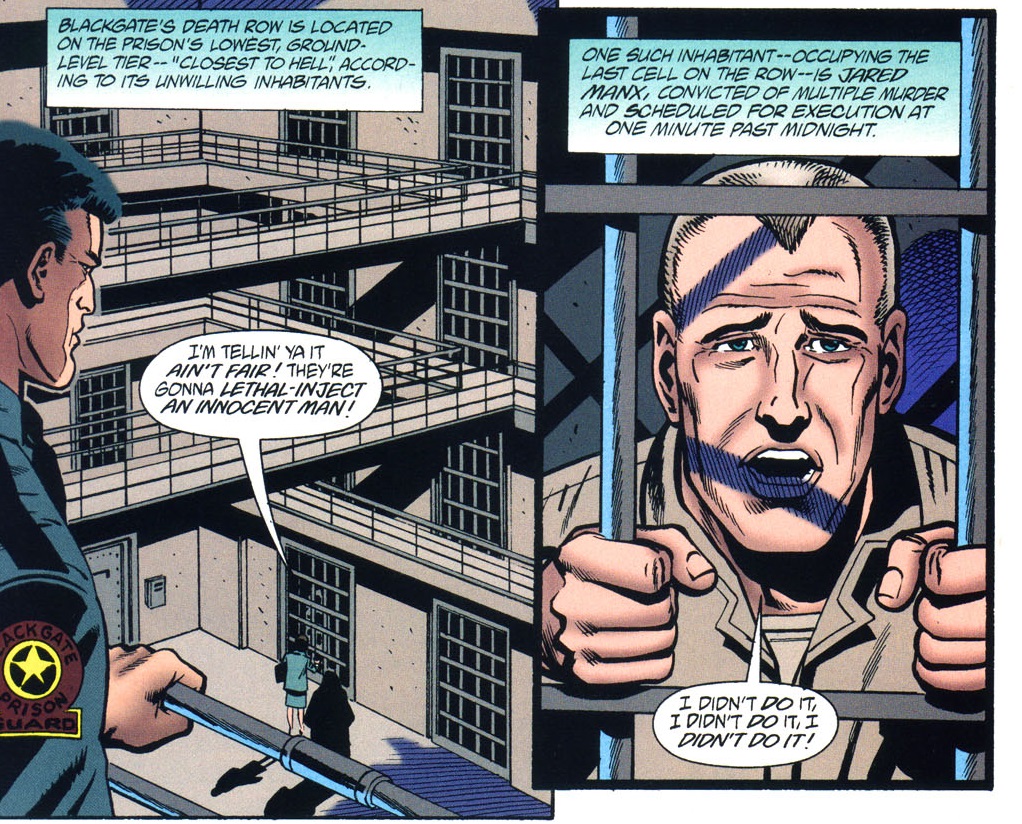

Written by Moench and drawn by Jim Aparo – with tight inks by David Roach and colors by Pat Garrahy – Isle of Men may not be the greatest exploration of the Blackgate corner of Batman comics, but it is worth a read due to a nice hook: at the heart of the story is Jared Manx, a prisoner who was waiting to be executed when the earthquake struck and who now takes the opportunity to try to prove once and for all that he is an upstanding citizen.

Blackgate: Isle of Men

Blackgate: Isle of Men

Chuck Dixon didn’t stay away for long. Cataclysm was followed by another major crossover: the extended No Man’s Land storyline, in which post-quake Gotham City is cut off from the rest of the country. A desperate Dark Knight then lets the authoritarian vigilante Lock-Up temporarily run the prison with an iron fist…

Nightwing #35

Nightwing #35

Of course, it’s only a matter of time until all this power rises to Lock-Up’s head and he goes too far, so in the kickass Nightwing three-parter ‘The Belly of the Beast/Nothing But Time/Escape from Blackgate’ (#35-37) it’s up to Batman’s former sidekick to take the power back.

The result is wall-to-wall action – via the ultra-dynamic pencils of Scott McDaniel, with thick inks by Karl Story – as Nightwing has to fight all the usual cast of oddball inmates, plus a handful of interchangeable Z-listers Dixon had introduced in the meantime, with names like Monsoon, Tumult, and Dynamiteer. There is even a classic Dixon sequence in which a bunch of characters find themselves in a rigidly confined space (the prison’s cellar) desperately struggling against time to get out.

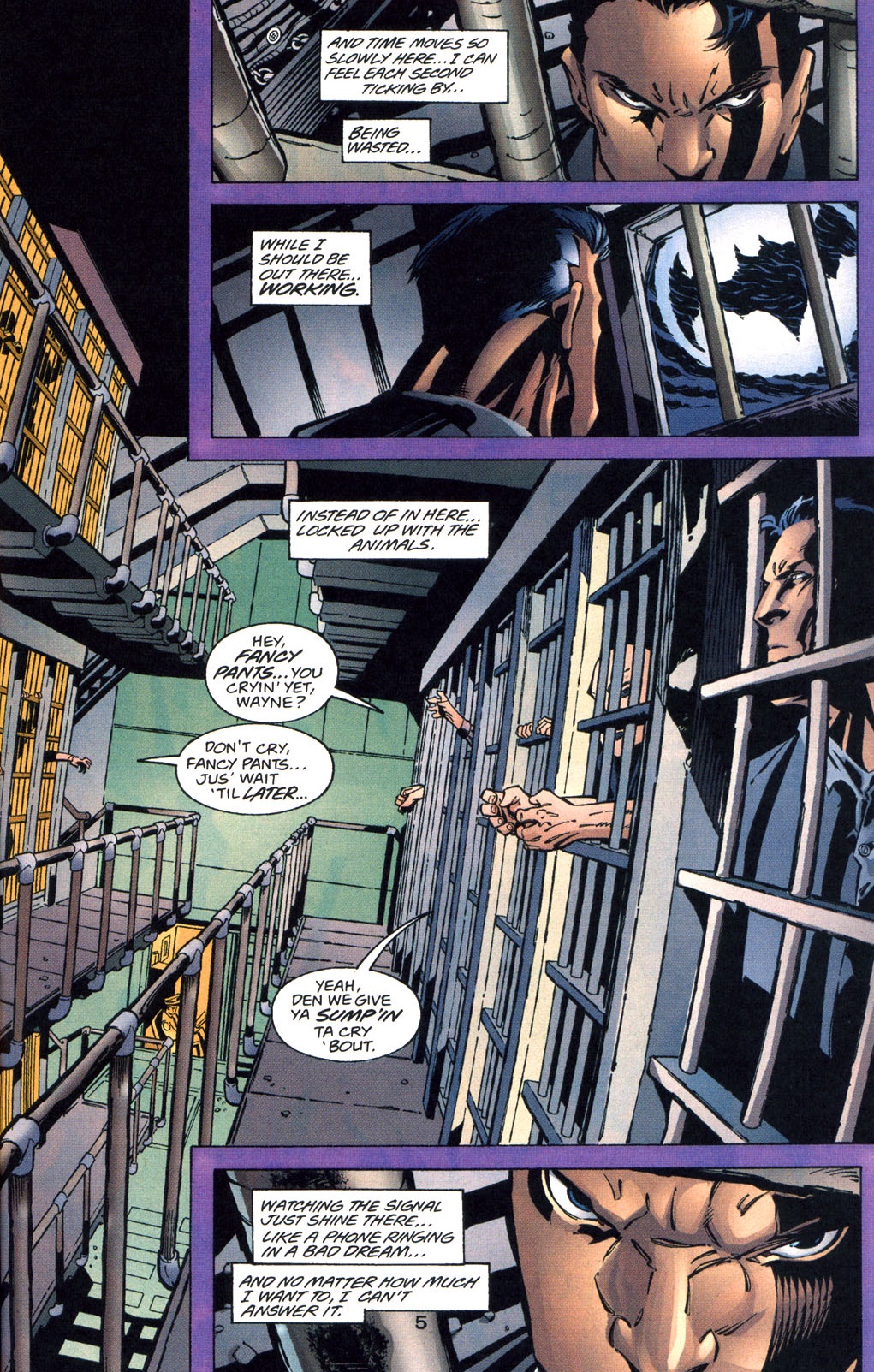

In turn, the next big crossover, Bruce Wayne: Murderer?, was a wasted opportunity. In this 2002 event – Batman comics’ answer to the O.J. Simpson trial – Bruce is accused of murdering his ex-girlfriend and is sent to Blackgate Penitentiary to await trial.

Batman #599

Batman #599

(You know it’s an Ed Brubaker comic because the protagonist explicitly tells you what he is feeling.)

Sure, the issue mines the drama you can get from having Bruce Wayne in prison without wanting to reveal himself as Batman… But the story never goes beyond the obvious hooks. Instead of having Bruce tip his hand by beating up other prisoners, it would’ve been nicer to see him take control, somehow, cleverly manipulating his surroundings while drawing on the knowledge he already has about the prison and its inmates. Hell, there isn’t even anything to distinguish Blackgate from any other prison, since the inmates are just a collection of stereotypes (skinheads, street gangs…) instead of stripped-down versions of Gotham’s eccentric criminal underworld, like in Dixon’s comics. The result is one of those Batman tales that takes itself so seriously that it forgets to be fun.

Linked to this crossover, Greg Rucka did write a couple of strong issues (Detective Comics #767 and #772) about Bruce’s bodyguard – Sasha Bordeaux – in Blackgate, but, likewise, there was nothing special about this version of the setting. It was just another generic prison. The problem, of course, is that prisons are horrible, depressing places, so approaching Blackgate realistically – rather than like an offshoot of Gotham’s distorted reality – creates a much more downbeat experience, one that inevitably casts Batman (who spends his life sending people to prison) in a much more negative, unheroic light.

Then again, you can go too far in the opposite direction. Blackgate was a key setting in 2013’s Arkham War, where Bane made the penitentiary his headquarters and its inmates his army in an attempt to conquer Gotham, which had recently been taken over by Arkham’s rogues. Despite introducing a promising new warden, Agatha Zorbato, this comic is utter dreck. Among its many flaws is the approach to Blackgate, which doesn’t come across as a prison at all, but more like an island where a bunch of assorted villains happen to hang out (in full costume!) and whose main contribution to the story is that it harbors a secret basement with cryogenically frozen assassins.

Thus, after a prelude drawn by Graham Nolan (shamelessly evoking much better Bane comics), writer Peter Tomasi and artist Scot Eaton manage to both miss the point of prison’s levelling effect (these criminals basically look and act the same as they did outside) and impose a whole new dehumanizing layer through their own storytelling (by treating all these different people as a single evil mindless horde).

Forever Evil: Arkham War #1

Forever Evil: Arkham War #1

I still think Blackgate Penitentiary has great potential, both as an interesting setting in its own right and as a provocative vehicle to occasionally recontextualize the Dark Knight’s mission. It makes sense to treat it as a prison bursting through the seams with weird criminals, since the fact that Gotham City is full of weird crime lies at the basis of Batman comics in the first place (just like the fact that Mega-City One is full of dumb assholes lies at the basis of Judge Dredd comics), presenting its heroes as an extreme/goofy response to an extreme/goofy problem.

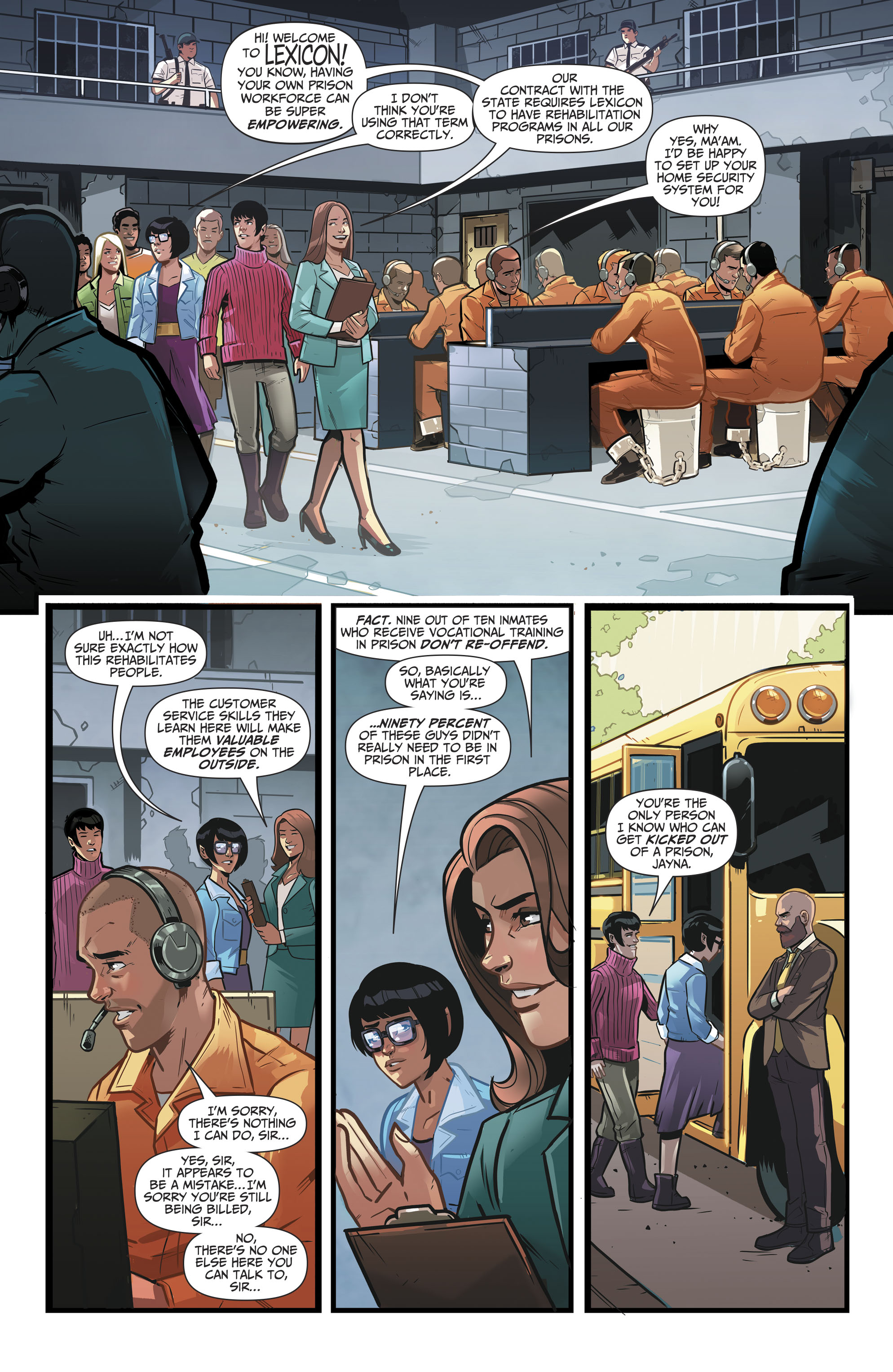

I wish creators would continue to use Blackgate in clever, amusing ways, like they did in the 1990s. Hey, since it is set in the DCU anyway, why not have it become part of Lex Luthor’s prison-industrial complex, bringing in Batman’s rogues gallery to further develop the satirical premise recently introduced in Wonder Twins?

Fantastic piece. Today, Blackgate is used more like Arkham part 2 than a unique place in Batman mythos. Sometimes I wish that Batman editorial team could be more like Dennis O’Neil in the 90s. Somehow, Gotham felt more vivid.

You and me both.

You should check out the VR game “Batman: Arkham Shadow”. Batman goes undercover in Blackgate like in “Hatred’s Home” to suss out the leader of an anarchist cult based on the Ratcatcher. It does a great job distinguishing Blackgate from Arkham (it’s a mega prison run by a private military company) and has some pointed commentary about corruption in Gotham, how crime is a structural issue, and vigilante justice as punishment vs rehabilitation.