When I wrote about Quentin Tarantino films last month, I promised to follow up with comic suggestions for fans of The Hateful Eight. I’ll include a couple of recommendations in my next post, but before that let me share a few thoughts on why I just can’t get enough of westerns!

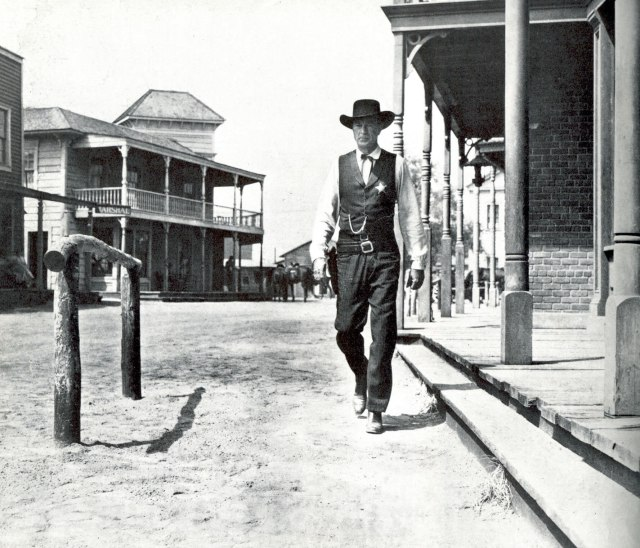

High Noon (1952)

High Noon (1952)

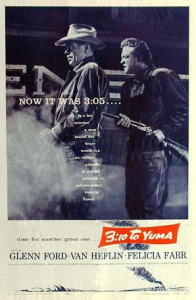

First of all, there is something about the time distance and the ‘simplicity’ of the surroundings. The natural landscapes, the small villages, the whole quasi-lawlessness thing… all this allows for basic themes (honor, revenge, justice, redemption, law and order) to be explored at their core in an almost allegorical way, uncontaminated by the caveats of a more recognizable setting or a more complex context. Some of the greatest westerns, like Henry King’s The Gunfighter or Delmer Dave’s 3:10 to Yuma, are essentially super-suspenseful morality plays.

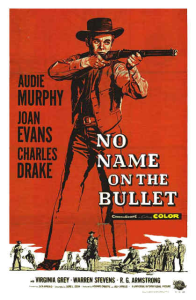

This is not to say that there is no room for moral complexity. It pisses me off how every time critics are trying to sell you on a western they try to contrast it with the supposedly clear-cut morality of the old ‘good guys vs bad guys’ formula (it’s the same thing with superheroes, really). In fact, filmmakers have been telling murky stories in this genre for more than half a century… If you go back to the ‘50s, you can find loads of thoughtful oaters, from classics like Bend of the River to more obscure flicks like No Name on the Bullet.

Comic writers, used to exuberant spectacle, often get bored with the limitations of western conventions (this is why every few years Jonah Hex finds himself in a post-apocalyptic future, or batting zombies, or flying around in the steampunk airship of Ra’s al Ghul!). Yet in cinema the relatively limited number of occupations and settings often leads to a kind of economical storytelling that appeals to me… Settled with mostly uneducated characters and unable to hide behind modern pop culture references, screenwriters go for terse dialogue and minimalistic symbols in order to convey plot and characterization. This means you have to concentrate to make sure you pick up everything that’s going on, which can make for quite an engaging viewing experience.

Director Budd Boetticher, screenwriter Burt Kennedy, and actor Randolph Scott did a series of unpretentious chamber westerns that got the most out of this sense of simple clarity (the best of the lot is 1959’s Ride Lonesome). Yet the guy who really elevated this type of craftsmanship to a whole other level was Sergio Leone, especially starting with For a Few Dollars More.

Clint Eastwood as the Man with (supposedly) No Name

Clint Eastwood as the Man with (supposedly) No Name

Many ‘spaghetti westerns’ followed Leone’s handbook, keeping the words sparse, the mood serene, and the action visually driven. My favorite in this mold is actually the French Cemetery without Crosses (also known as The Rope and the Colt). Another worthy French entry is the recent Far from Men, which is not exactly a western (it’s set in the Algerian war) but it sure feels like one!

(That said, this tendency can be taken to an infuriating extreme, like with Monte Hellman’s The Shooting or Alejandro Iñarritu’s The Revenant… both look quite pretty, though.)

Most of all, there is something purely *cinematic* about westerns. The atmosphere of constant tension because of the ease with which people can kill, the cathartic power of a shot, the feel of chivalrous adventure from all the horse-riding, the gravitas of these archetypes, the scenic backgrounds… There is a reason why the most defining examples of the genre (Ford’s Stagecoach, Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch) are not merely great westerns – they are some of the most freaking iconic cinema masterpieces of all time!

Stagecoach (1939)

Stagecoach (1939)

Sure, there are shitloads of duds, but the ingredients are there to make it work fairly easily. At least two beloved westerns simply relocated Akira Kurosawa’s samurai epics to the American Wild West (A Fistful of Dollars is a rip-off of the awesome Yojimbo and John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven is a remake of Seven Samurai), yet they both turned out to be highly entertaining pictures in their own right. Johnny Guitar may end on kind of a weird note, but that opening half an hour is worth its weight in gold. Hell, throw in enough double-crosses and competently crafted set pieces, and even a middle-of-the-road dustraiser like Buchanan Rides Alone can be a darn enjoyable way to spend 78 minutes.

Basically, if you add an operatic Ennio Morricone score to the image of a gunfighter on a horse, then you’re halfway there to producing a satisfying movie. To be fair, it doesn’t even have to be Morricone – many westerns rely on atmosphere stitched together by a cool soundtrack, whether it’s Bob Dylan songs in Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid or Leonard Cohen tracks in McCabe & Mrs. Miller. (Then again, Rancho Notorious is as vicious as any other Fritz Lang movie, but it only works if you disregard the fact that it’s punctuated by a hilariously mismatched ballad that serves as a bizarre, baritone Greek chorus.)

And if the sheer number of instantly recognizable tropes makes it easy to use shorthand and achieve intertextual resonance, it also lends itself to obvious parody. Besides genre spoofs (the funniest is still, by far, Blazing Saddles), there are plenty of hybrids that work simultaneously as westerns and as comedies. I’m not a big fan of the lowbrow slapstick of the Trinity movies starring Terence Hill – also known as ‘fagioli westerns’ – but I do get a kick out of the tongue-in-cheek zaniness of Sam Raimi’s The Quick and the Dead (not to mention the third Back to the Future). And while Destry Rides Again doesn’t make me laugh out loud, I do find it incredibly charming.

Destry Rides Again (1939)

Destry Rides Again (1939)

Indeed, even if you regard the western as a proper genre (and not merely as a shared historical setting), it is loose enough to easily allow for crossbreeding. In the 1940s, some directors approached it with a cool film noir sensibility, for example in the stylish Winchester ’73 and Yellow Sky (not to mention John Huston’s angry neo-western The Treasure of Sierra Madre). In the 1950s, the supernatural anthology TV show The Twilight Zone had a bunch of episodes set in the Old West, including ‘Mr. Denton on Doomsday,’ ‘The Grave,’ and ‘Dust’ (the show’s creator, Rod Serling, also wrote the lesser-known, straight-up western drama Saddle the Wind). Among the most accomplished attempts to fuse westerns with a horror vibe, you can find 1970’s And God Said to Cain as well as last year’s Bone Tomahawk.

The latter are also violent as hell, because no-holds-barred sound and fury is another thing westerns can deliver like nobody’s business.

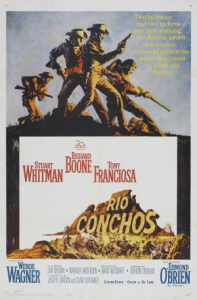

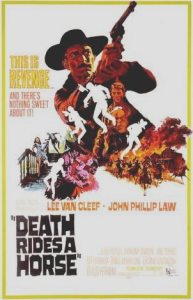

Americans have come up with their fair share of gritty westerns (particularly Gordon Douglas, the man behind Rio Conchos and Barquero). If you are into raw, visceral insanity, though, few movies can match the power of Italian horse operas like Death Rides a Horse.

And in terms of pure brutality, there is of course Django – you know, the one with the dude dragging his coffin around and inspiring countless imitations, homages, and kick-ass songs.

Django (1966)

Django (1966)

NEXT: More on westerns.