One of the things I enjoy doing at Gotham Calling is to quickly zoom in on specific skills and quirks of the many awesome artists of Batman comics, from Don Newton and Tim Levins to Graham Nolan and Frank Robbins. Today, I want to spotlight one of my favorite traits of Enrique ‘Quique’ Alcatena, namely his flair for adorning panel borders with flourishes that bring out each story’s core motifs…

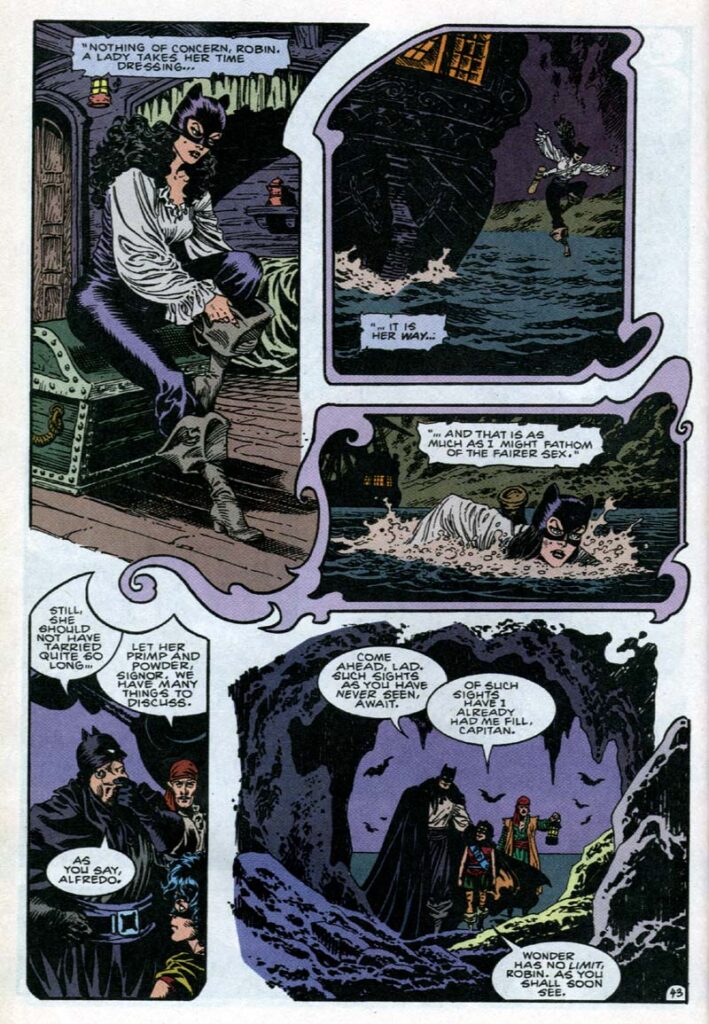

Detective Comics Annual #7

A self-taught Argentinian artist, Quique Alcatena entered British comics in the late 1970s and eventually made his way to DC, where his first Batman work was this 1994 swashbuckling period piece set in an alternate reality where the Dark Knight is an English pirate called Leatherwing who targets Iberian galleons in the Caribbean.

Ah, pirates… It’s not too much of a stretch to see a family tree growing from these violent outlaw figures operating by their own code (at least as depicted in popular culture) to Zorro and, by extension, to the Caped Crusader strand of virile, if campy, vigilantes. Now, as far as pirate comics go, this one isn’t as nastily funny as Isle of 100,000 Graves or Portrait of a Drunk, but Chuck Dixon’s script is nevertheless highly amusing, what with its quaint turns of phrase, rhymed narration, and the way it reimagines the Batman mythos (including a cathartic reversal of A Death in the Family). Alcatena’s deadpan – yet baroque – artwork helps sell the humor, redesigning the cast’s extravagant garments with a straight face while placing them in a lavishly illustrated adventure.

The ornate panel borders, beside serving a practical function in the pages’ layout (for instance, clearly separating the scene with an ersatz-Catwoman fleeing the ship from the one about Leatherwing, Robin, and Alfredo in this version of the Batcave – the Bat Cay), contribute to the whimsical faux-historical spirit. The arabesques above may resemble the jewelry one might find in Leatherwing’s treasure, but they’re clearly also meant to evoke the illuminated manuscripts of old… Or, better yet – and perhaps deliberately – they rather evoke the pastiche of such illuminations you could find in the sort of pulp magazines Dixon probably read for inspiration, so that the access to the 18th century is openly mediated by the fiction of a much more recent past, thus adding yet another layer of history – and intertextuality – to this Elseworlds tale.

(Dixon and Alcatena later reunited for a fun sequel entirely made of verses and splash pages, ‘The Bride of Leatherwing,’ published in Batman Chronicles #11.)

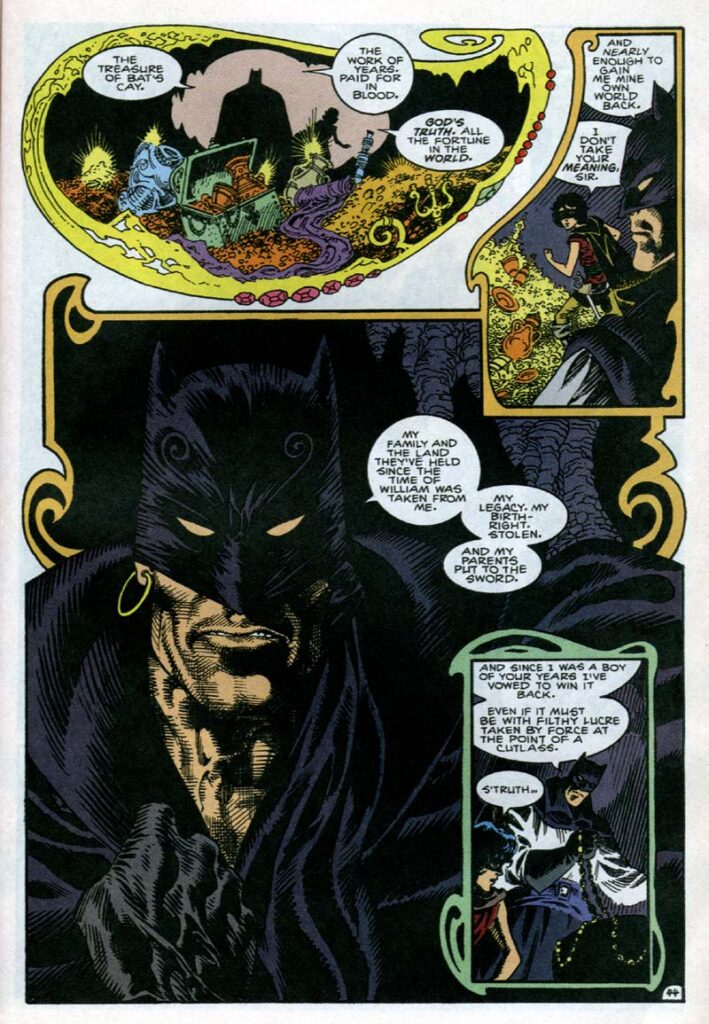

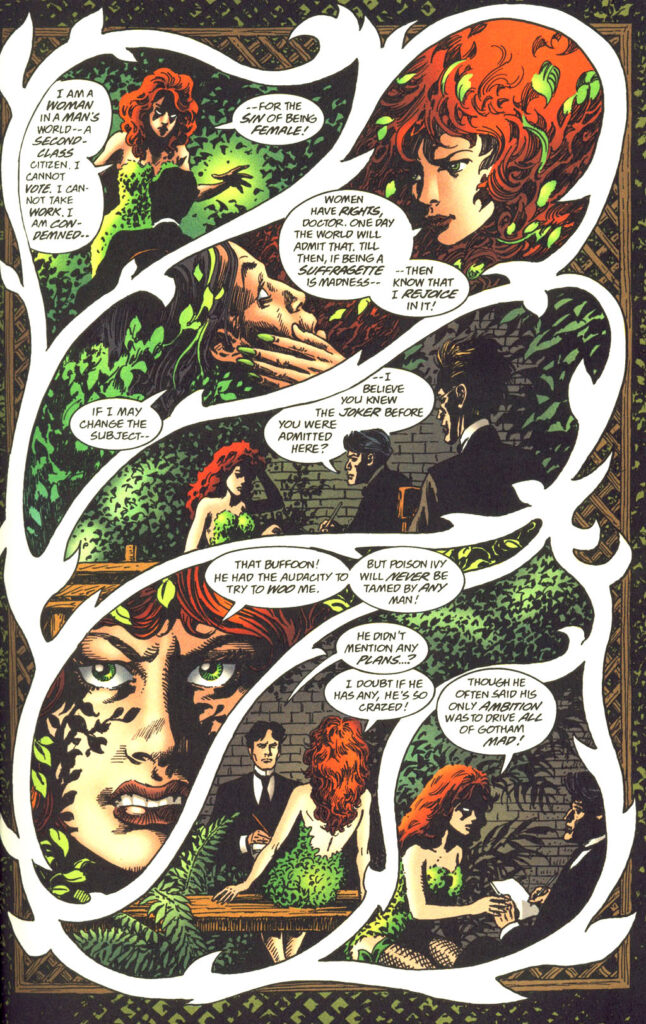

The Batman of Arkham

2000’s The Batman of Arkham one-shot is another Elseworlds tale, and another period piece, but instead of a pulpy romantic adventure, we now get a gothic horror psychodrama set in 1900 where a version of Bruce Wayne is a Freudian doctor in a post-Bedlam Arkham Asylum.

Tonally, it’s a very different comic. It was penned by Alan Grant, one of the most interesting and prolific Batman writers, who had an instinct for injecting even the most lowbrow material with his passionate political and philosophical concerns, often resulting in provocative and/or weird projects. Grant occasionally used the freedom and storytelling potential of Elseworld narratives not just to rearrange the Dark Knight’s tropes and aesthetics, but also to problematize the franchise’s values through recontextualization. In The Batman of Arkham, he challenges the series’ standard problematic depiction of mental illness as evil, unimprovable, and contained only through violence and incarceration… Here, such a worldview is linked to outdated, century-old ideas attributed to a villain (Jonathan Crane) and actively fought against by a hero who argues that ‘Men are made evil.’ (Plus, as you can see in the scan above, when it comes to women, the very notion of ‘evil’ is externally imposed in order to preserve reactionary social norms.)

Quique Alcatena pushed his quirky panel borders to a new degree. Besides enhancing specific atmospheres (dizzying in the first page above, which suits Poison Ivy’s hypnotic seduction moves; generally stiff and oppressive in the scene at the bottom of the second page, just like Crane’s conversation with Wayne), they appear to project characters’ states of mind, which makes thematic sense in such a psychological story.

Thus, the borders around Poison Ivy look like climbing vines, not least because they are superimposed over some kind of wooden garden fence that frames the whole page. This ties both into the fact that the character typically identifies with nature (reinforced by the leaves coming out of her hair, although that may have been an additional choice by colorist Noelle Giddings) and into how twisty and entangled Ivy is feeling at the moment, restrained as she is for the crime of seeking liberation. Likewise, the borders of the very final panels, around Bruce Wayne and Jonathan Crane, shift from a rational angularity to a sinister melted shape, a distortion that suggests the characters are heading in a darker direction (in the case of Crane, this is complemented by the unnaturalistic Scarecrow-ish shadow).

Grant and Alcatena formed quite a team. In fact, they had already partnered up a few years before, in Legends of the Dark Knight #89-90, where they had reimagined the origin of Clayface…

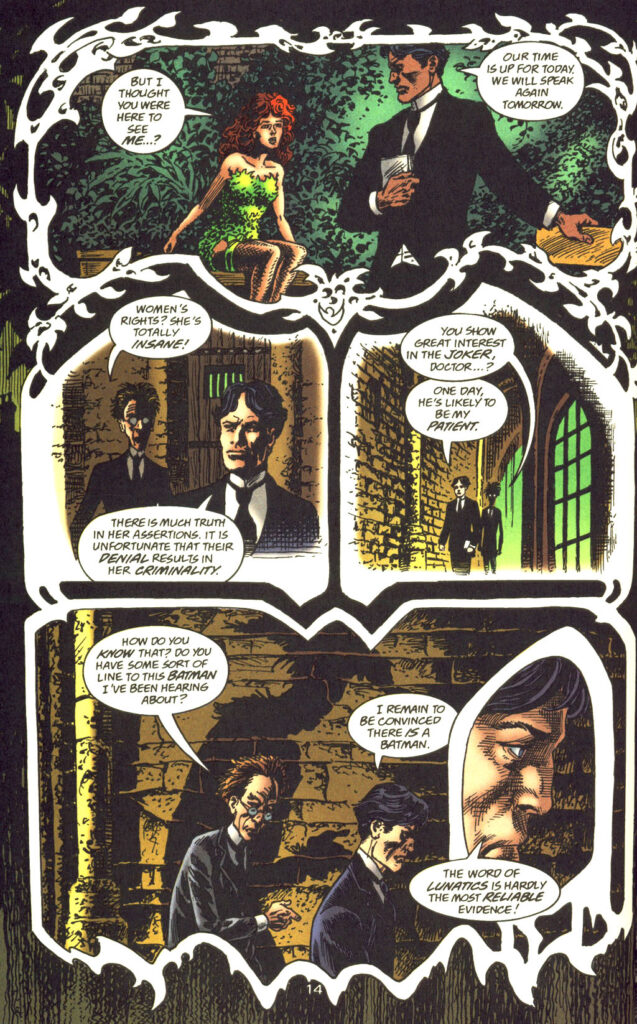

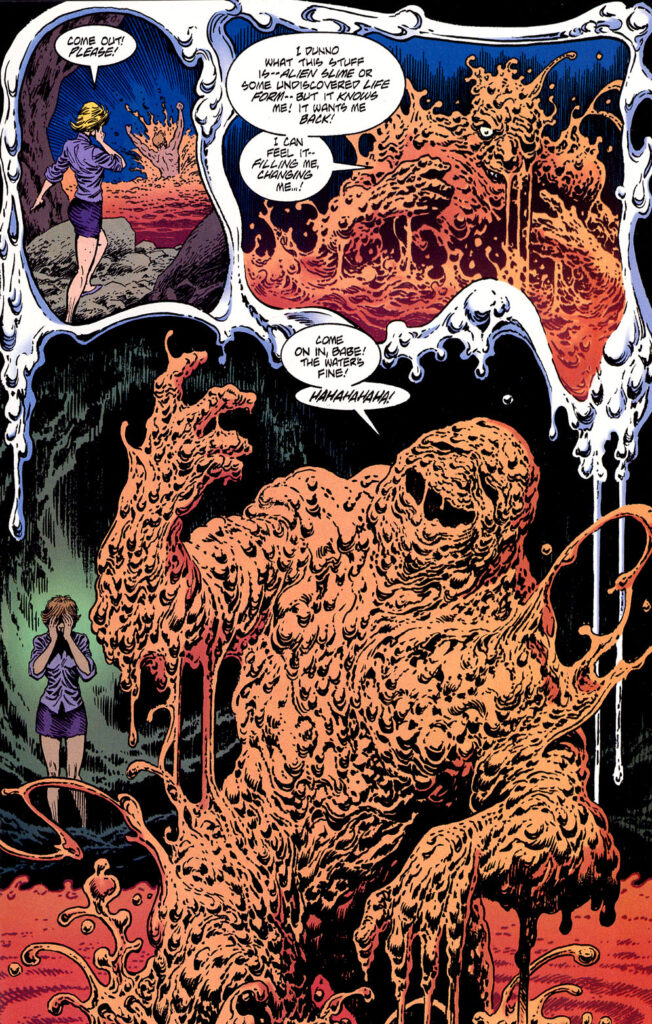

Legends of the Dark Knight #90

This image really stuck with me over the years. ‘Clay’ is both a horror story and a story about horror, as early-career Batman is still learning to cope with fear and supernatural threats… and here Quique Alcatena – ever a master of the medium – nails it perfectly, not just through Clayface’s horrifyingly grotesque design, but also through the eerie way the magical shape-shifting matter appears to contaminate the page’s whole layout. It is the stuff of nightmares: the squiggly panel borders stretching and dripping towards the bottom of the page somehow seem alive, fluid, unstable, and even gory.

While storywise ‘Clay’ is a loose remake of 1961’s Detective Comics #298, the artwork alone makes this a whole other beast. Alcatena’s skill in rendering both a monster *and* a monstrous mood sell the key impression that this is a scary – and deeply fantastical – world… one in desperate need of a certain masked hero.