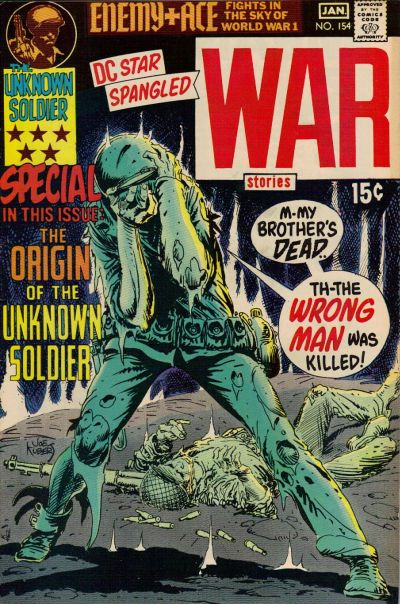

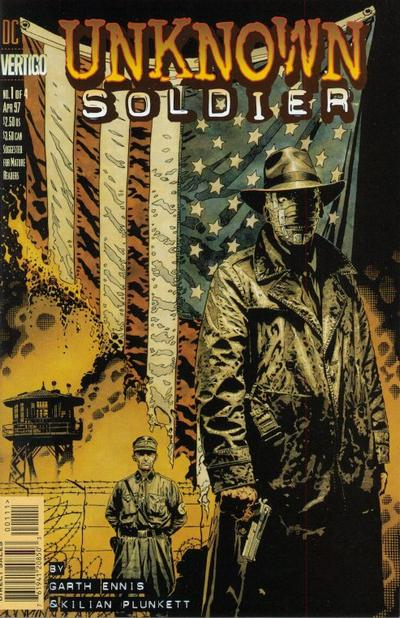

After being absent from the stands for about eight years, in 1997 the spy/war comic Unknown Soldier got the Vertigo treatment. By then, the Vertigo imprint had come to specialize in getting edgy (usually British) creators to reimagine third-tier DC properties through a much darker, mature, and modern sensibility. While editors Karen Berger and Shelley Bond had initially forged the imprint’s identity around literate horror, however, Axel Alonso seemed eager to open a parallel line devoted to violent crime and intrigue (he soon went on to edit Human Target and 100 Bullets) and this politically charged four-issue mini-series was just the sort of project that fit like a glove.

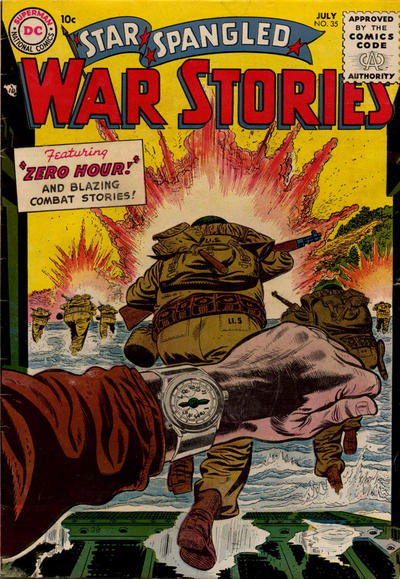

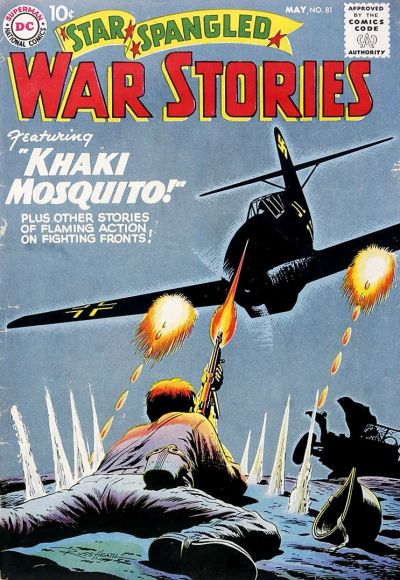

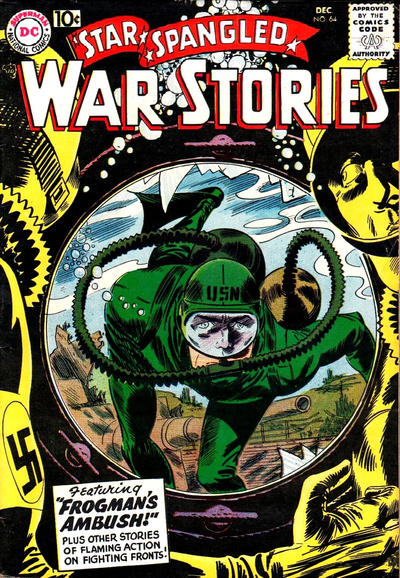

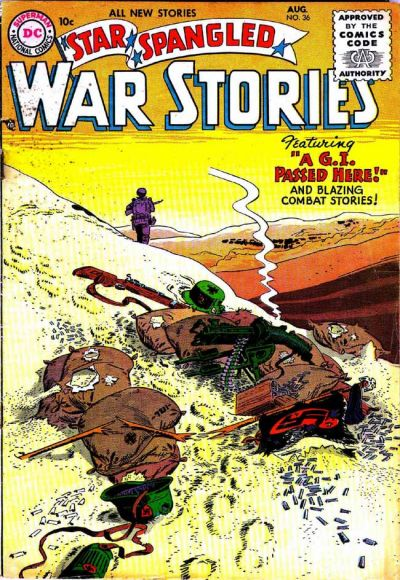

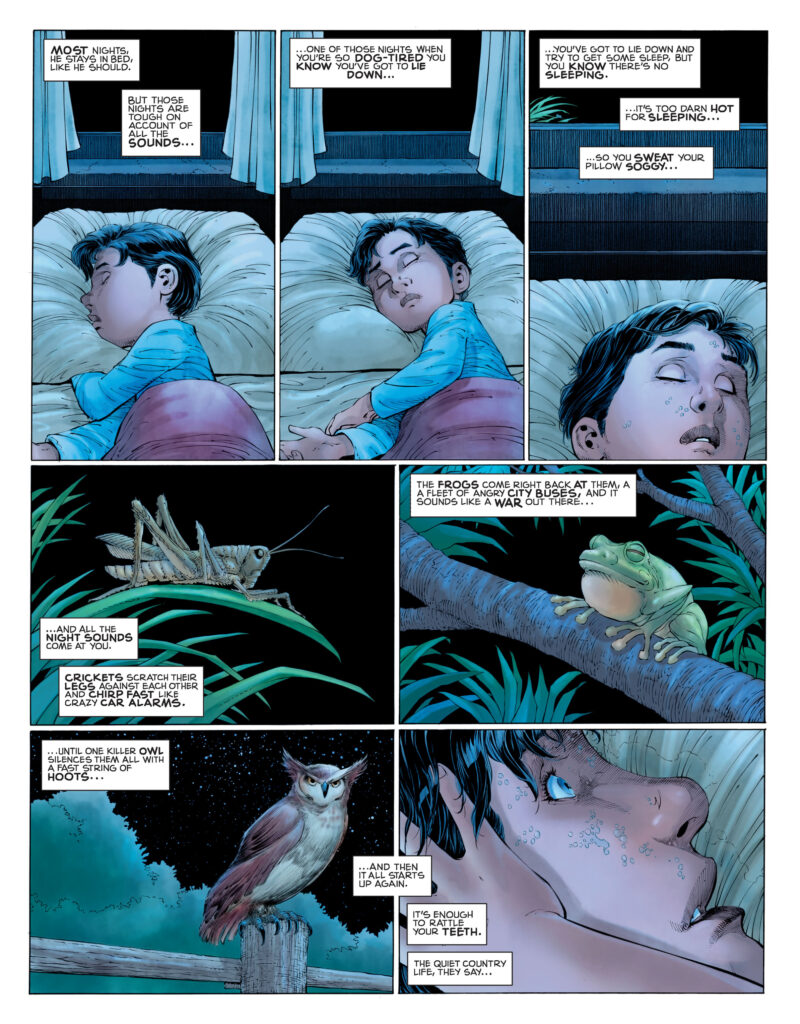

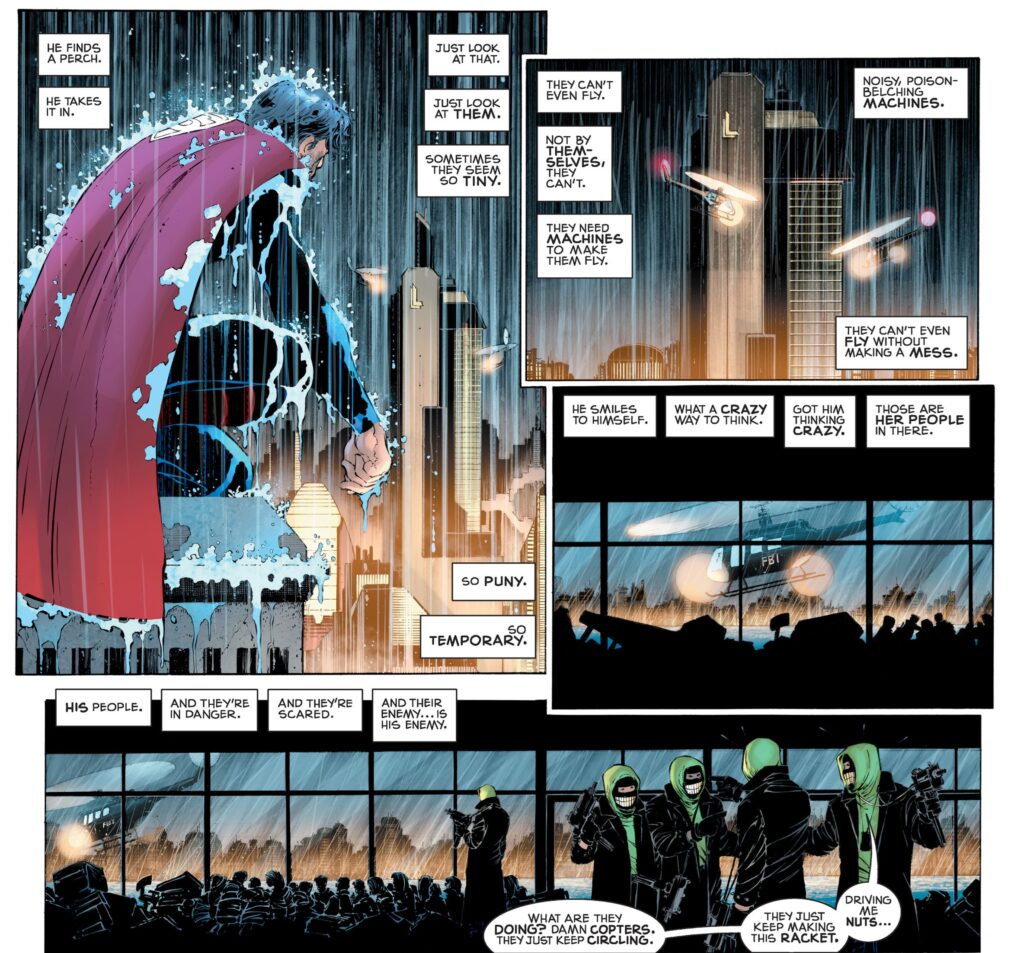

Asking Garth Ennis to update an old war comic may seem like a no-brainer today but, to Alonso’s credit, this was years before Ennis proved himself a master of the war genre and back when he was mostly known for writing humorous fantasy (most notably Preacher, edited by Alonso). Likewise, while Tim Bradstreet’s portentous, photorealistic compositions (see above) now look like classic Vertigo covers, as far as I can tell they were some of Bradstreet’s earliest cover work, so they forcefully conveyed the notion that this was not your daddy’s Unknown Soldier… The comic looked ‘serious’ and ‘relevant’ – check out that burning flag!

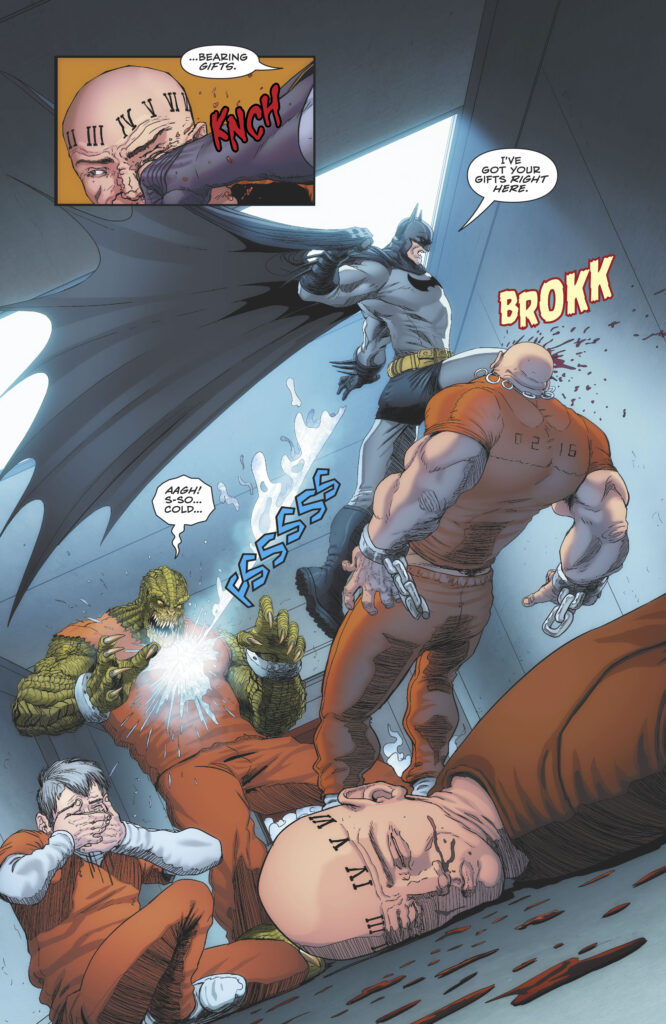

Plus, because it was Vertigo, you knew you’d get your share of gore and swearing…

Unknown Soldier (v3) #1

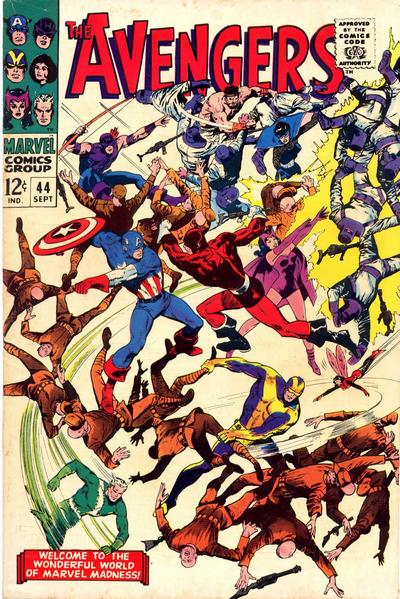

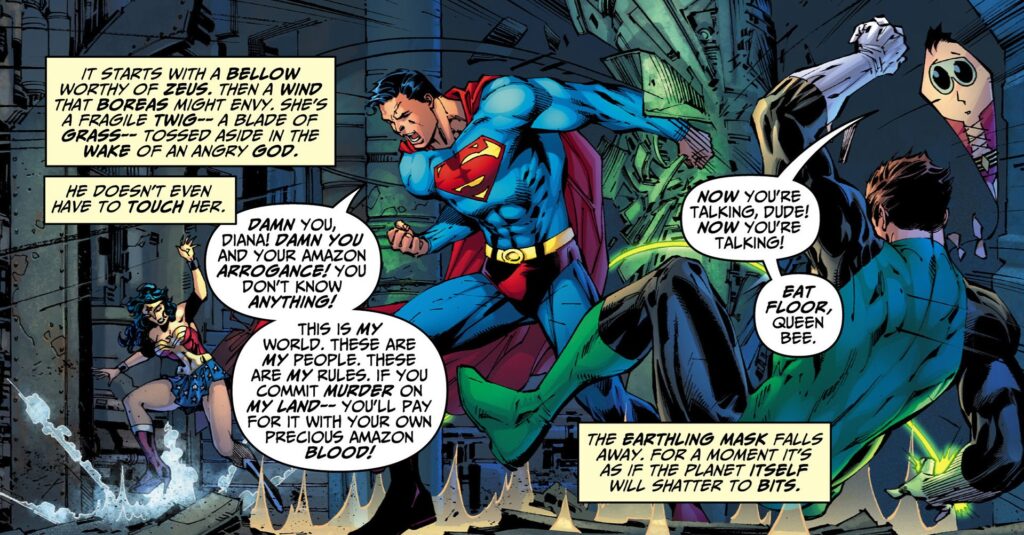

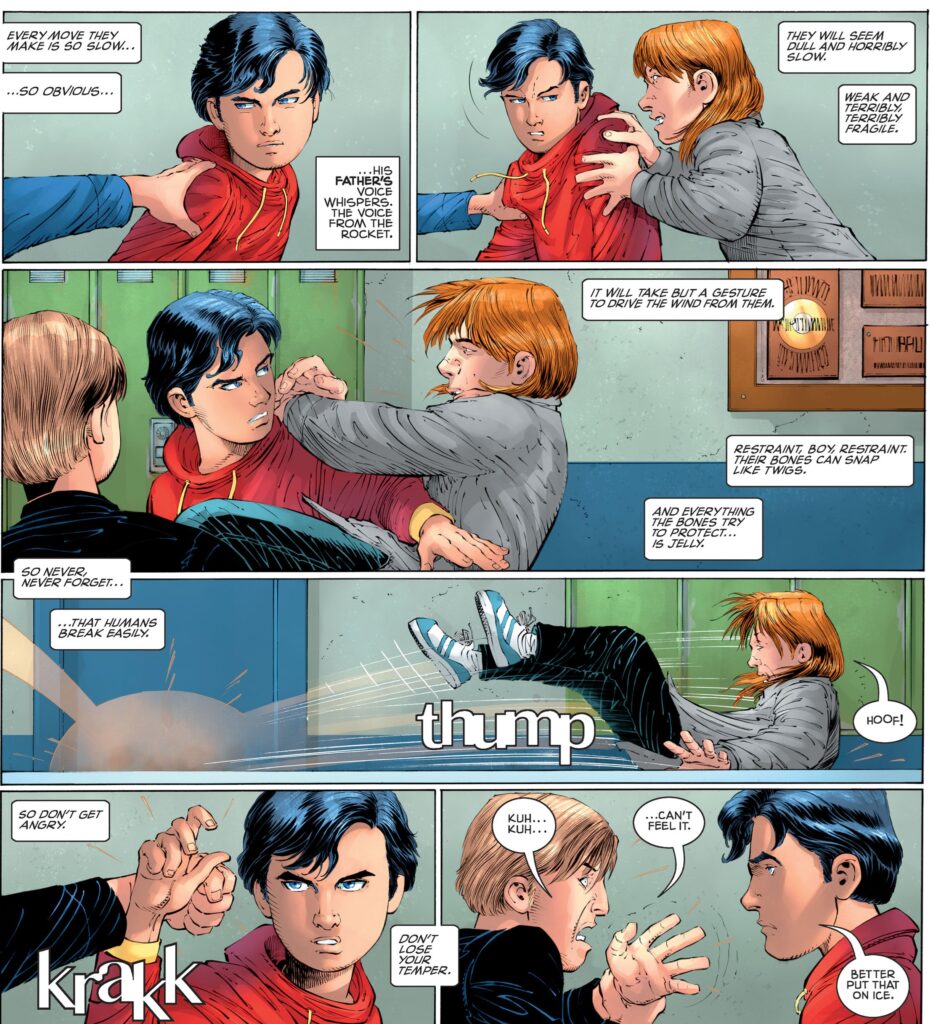

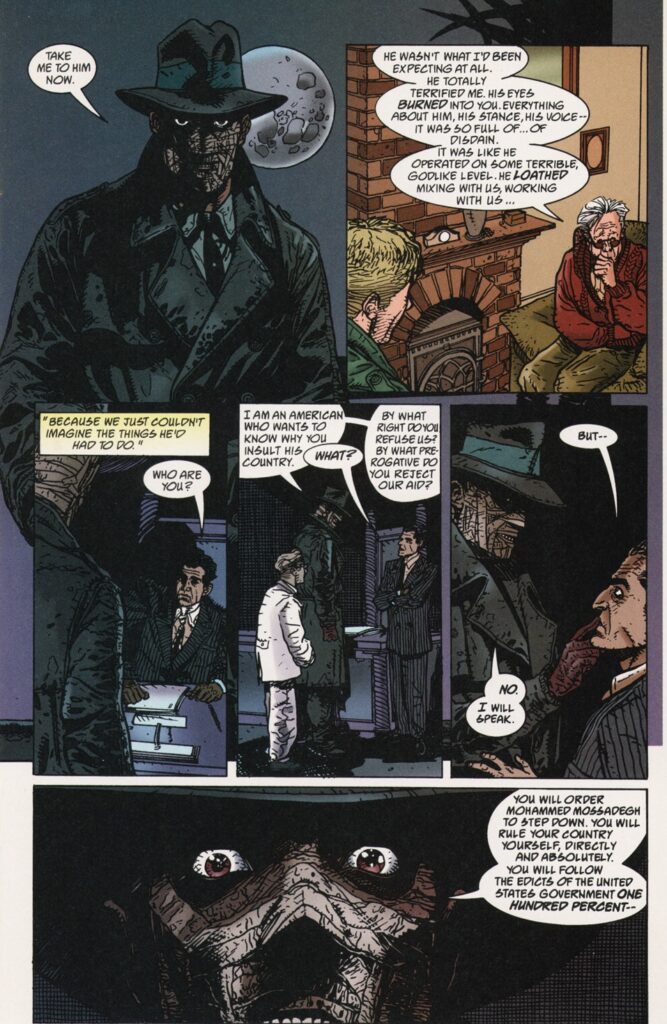

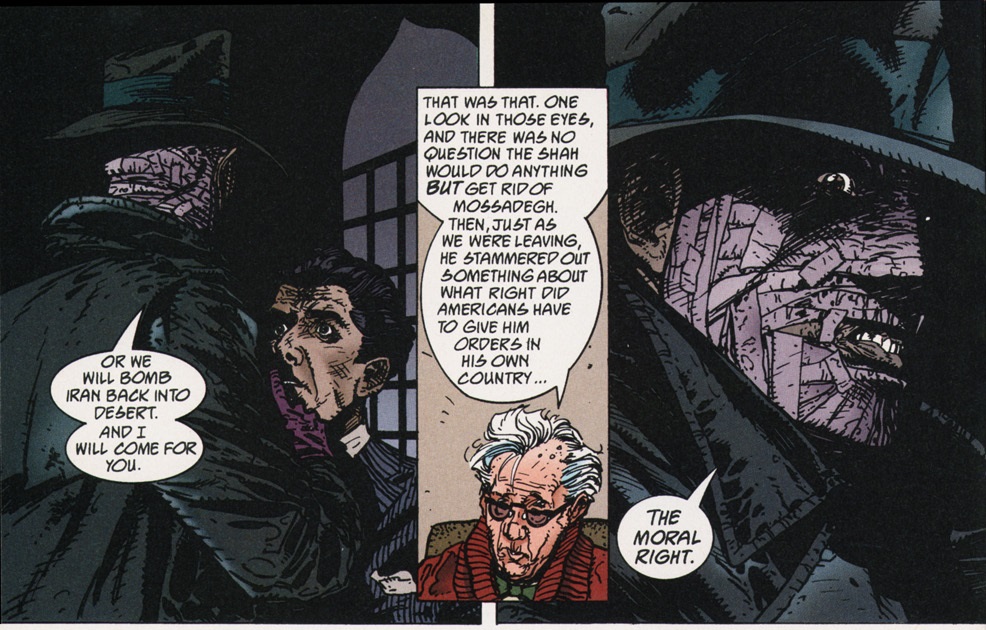

That said, the previous stab at the franchise, by Christopher Priest and Phil Gascoine (back in the late 1980s), had already been committedly revisionist, so this one felt more like a variation on that earlier reboot than like the next logical step. The premise is basically the same: what if you take the Unknown Soldier out of the supposedly ‘clean’ war of WWII and throw him into the morally ‘dirty’ Cold War? The big difference is that, instead of seeing things through the soldier’s eyes, we now get an outside perspective. The mini-series is pretty much a Pakula-like conspiracy thriller following the principled CIA agent William Clyde in an investigation about the mysterious Unknown Soldier which takes him on a tour of the agency’s history of atrocities across the decades in places like Iran, Cambodia, and Nicaragua.

Technically, the series can share the continuity of previous stories, as the Unknown Soldier certainly fought in World War II and stuck around since then. Yet his characterization is a far cry from the one in the Priest/Gascoine comics… There, he constantly doubted and resented the Cold War doctrine; here, he becomes its sinister embodiment.

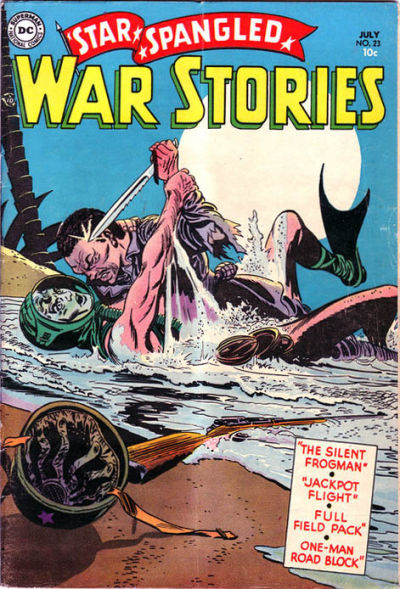

Unknown Soldier (v3) #2

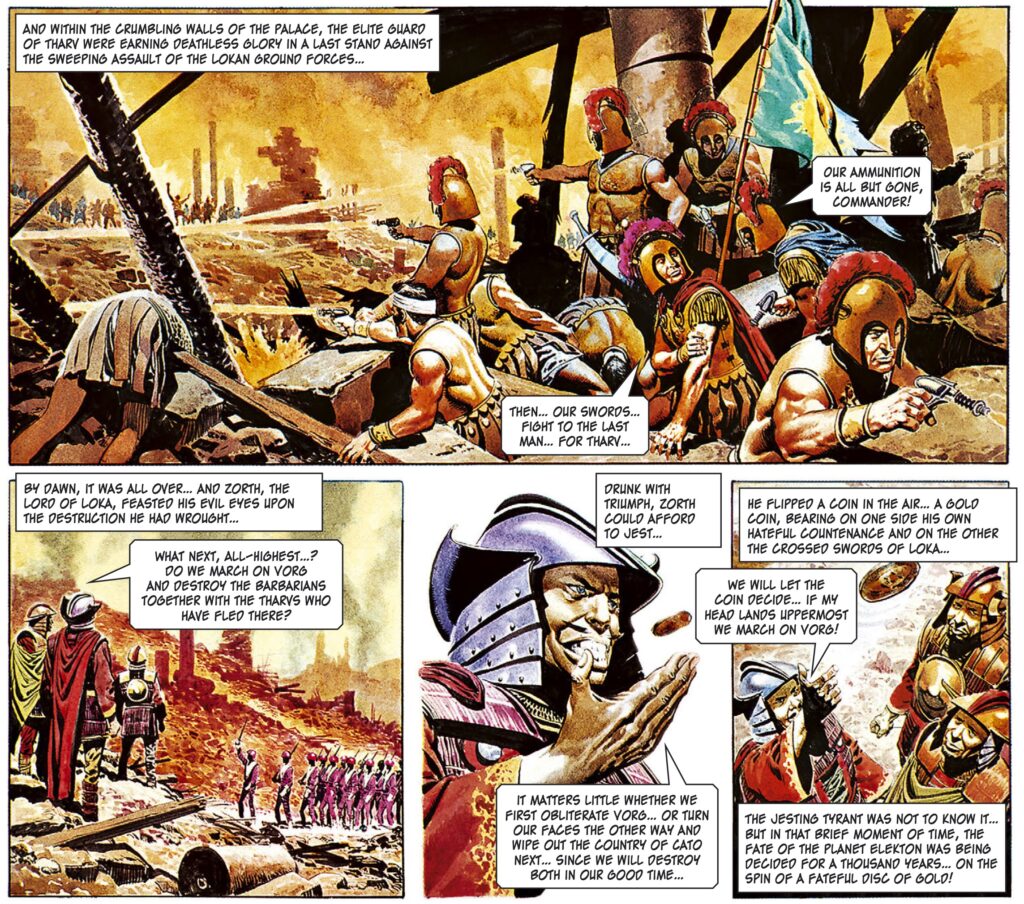

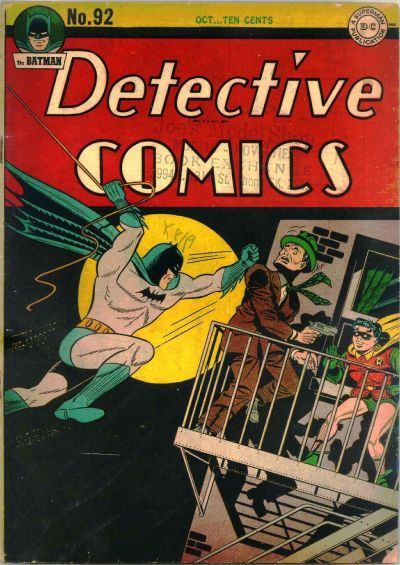

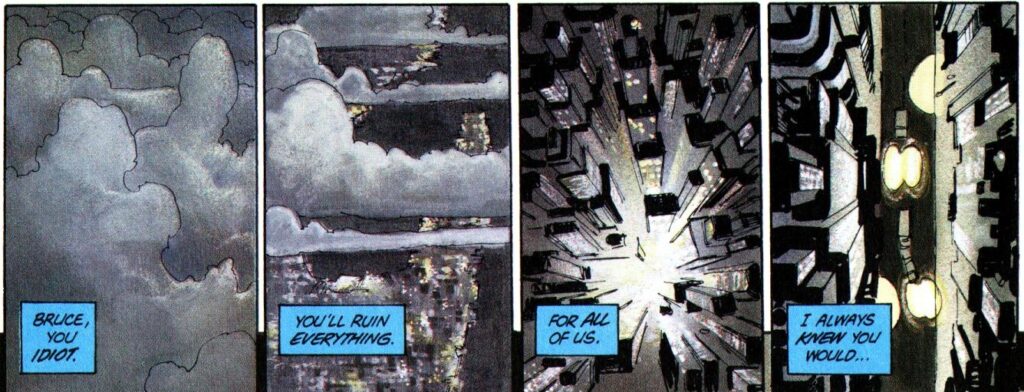

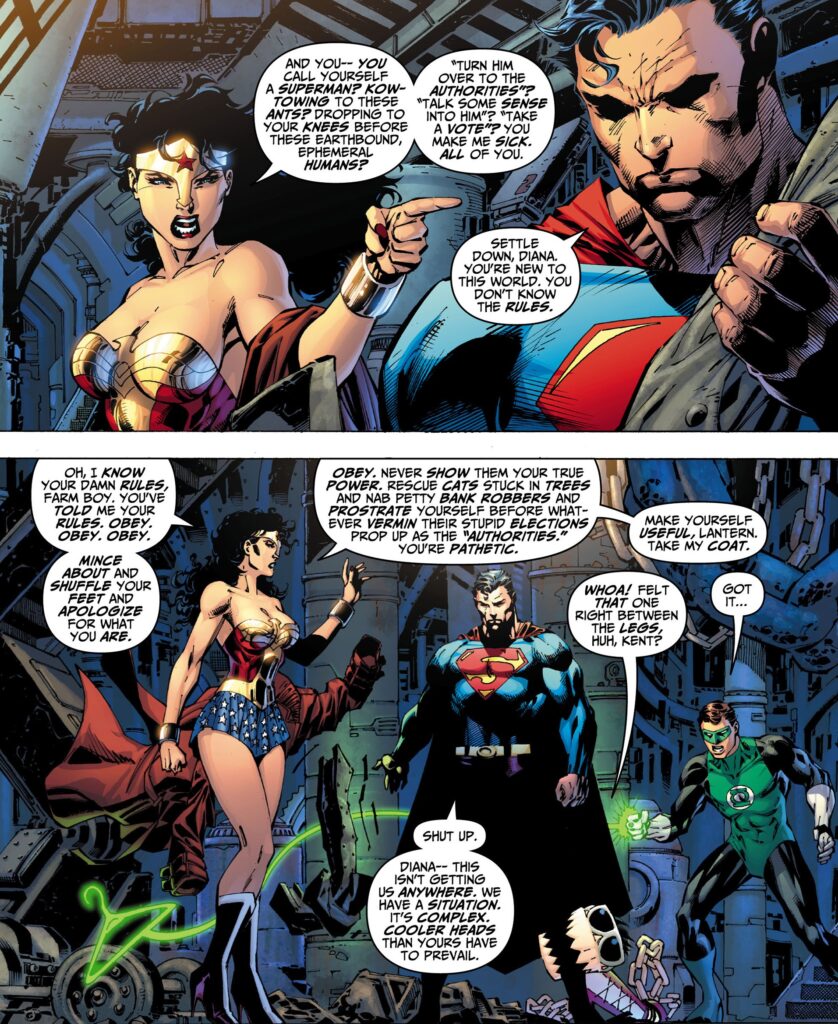

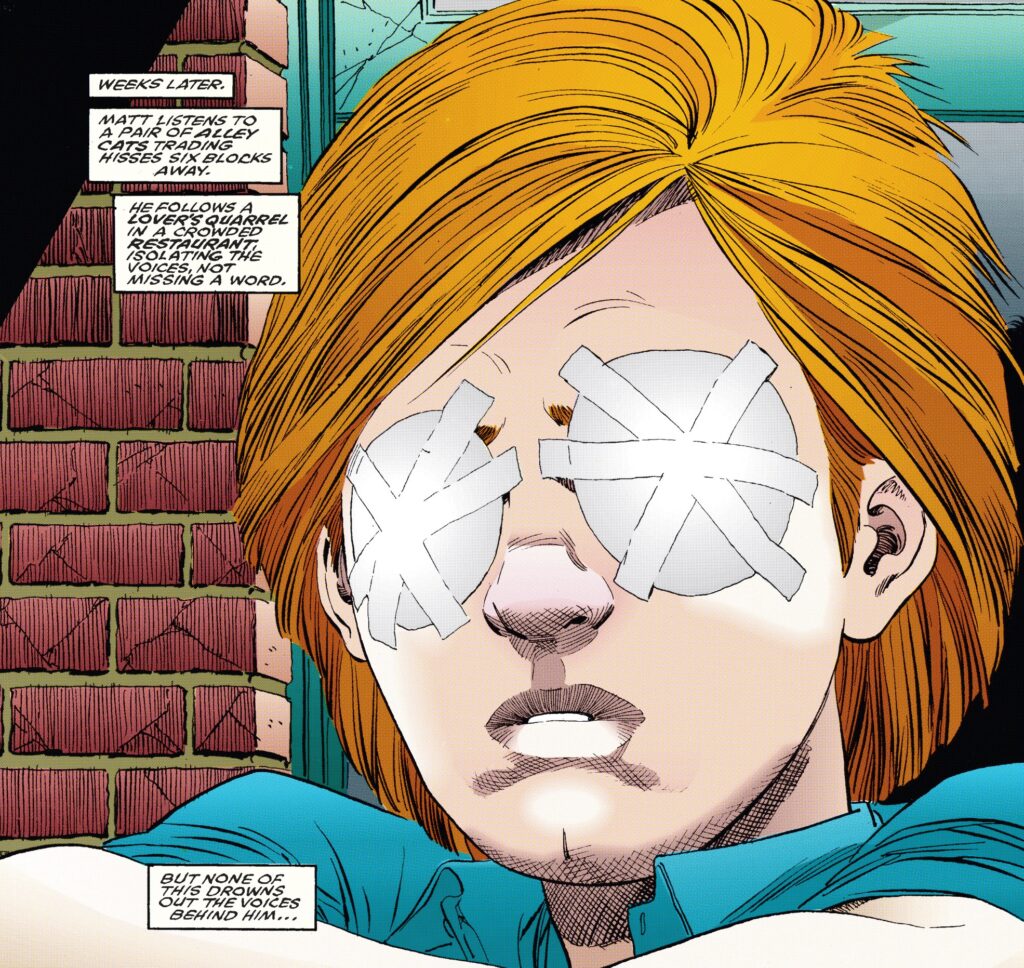

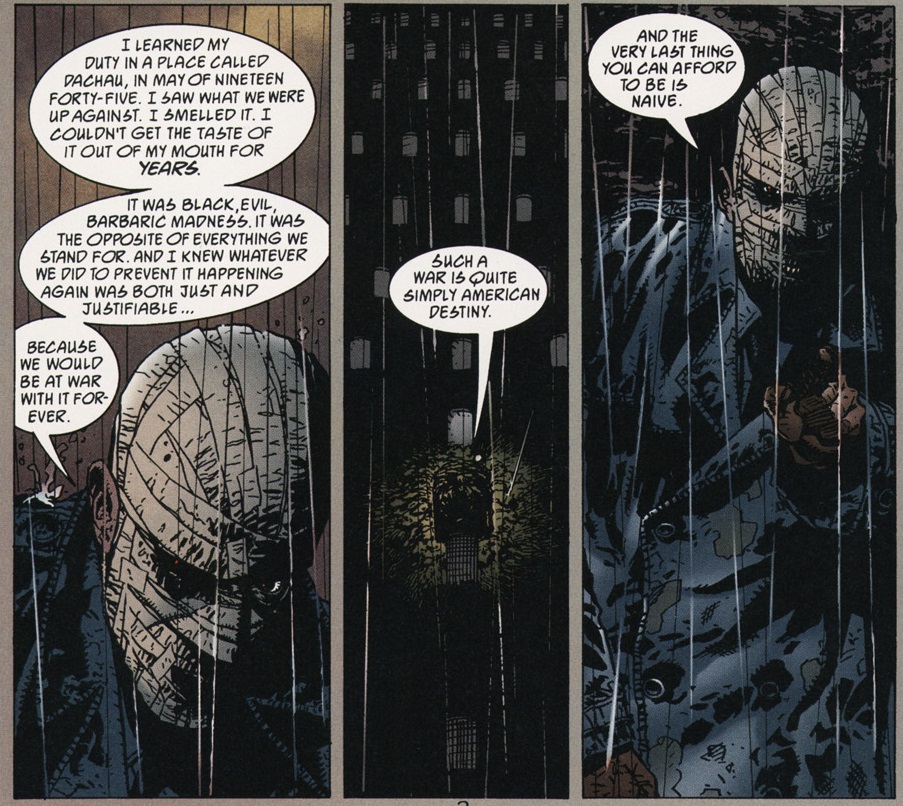

As you may have gathered from the scans so far, the comic posits that the Unknown Soldier’s/United States’ sense of righteousness derives directly from World War II and the Holocaust, as he henceforth felt morally superior and entitled – even obliged – to do everything in his power to prevent anything similar from ever happening again. Putting a spin on one of the franchise’s long-running catchphrases (‘One man, in the right place, at the right time, can make a difference. And win a war.’), the series considers how a sense of purpose, idealism, and humanitarian concerns can be warped and taken to a fanatical extreme, with terrifying results.

If you believe you are in a messianic crusade against Evil (capital letter and all), then all sacrifices are deemed acceptable. This is what happened to the US: the mythologization of WWII (including in the earliest tales of the original Unknown Soldier) ultimately justified – in the minds of Washington’s policymakers and of the public in general – American exceptionalism, foreign interventions, and an endless state of war.

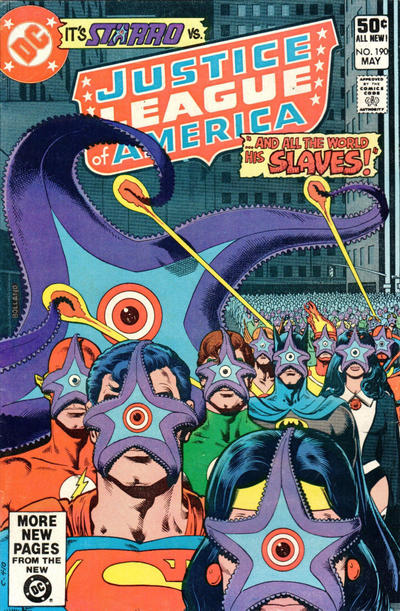

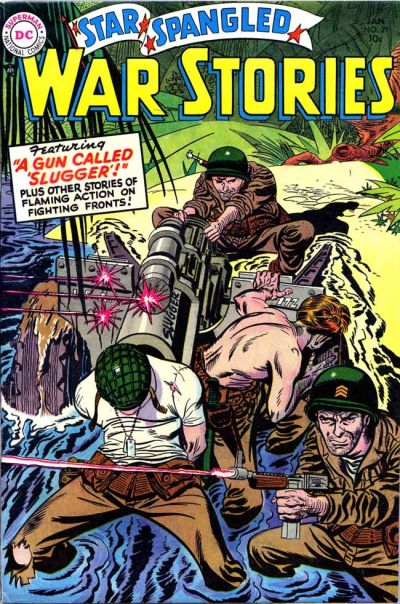

I’m not exactly reading between the lines here. The comic is not subtle:

Unknown Soldier (v3) #4

(It’s not every day I get to compare a Garth Ennis comic to a short story by Jorge Luis Borges, but this seems to come from the same place as ‘Deutsches Requiem,’ which suggests that Nazism ultimately won, even if the Third Reich was destroyed in Germany, since WWII impelled other nations towards ‘violence and faith in the sword.’)

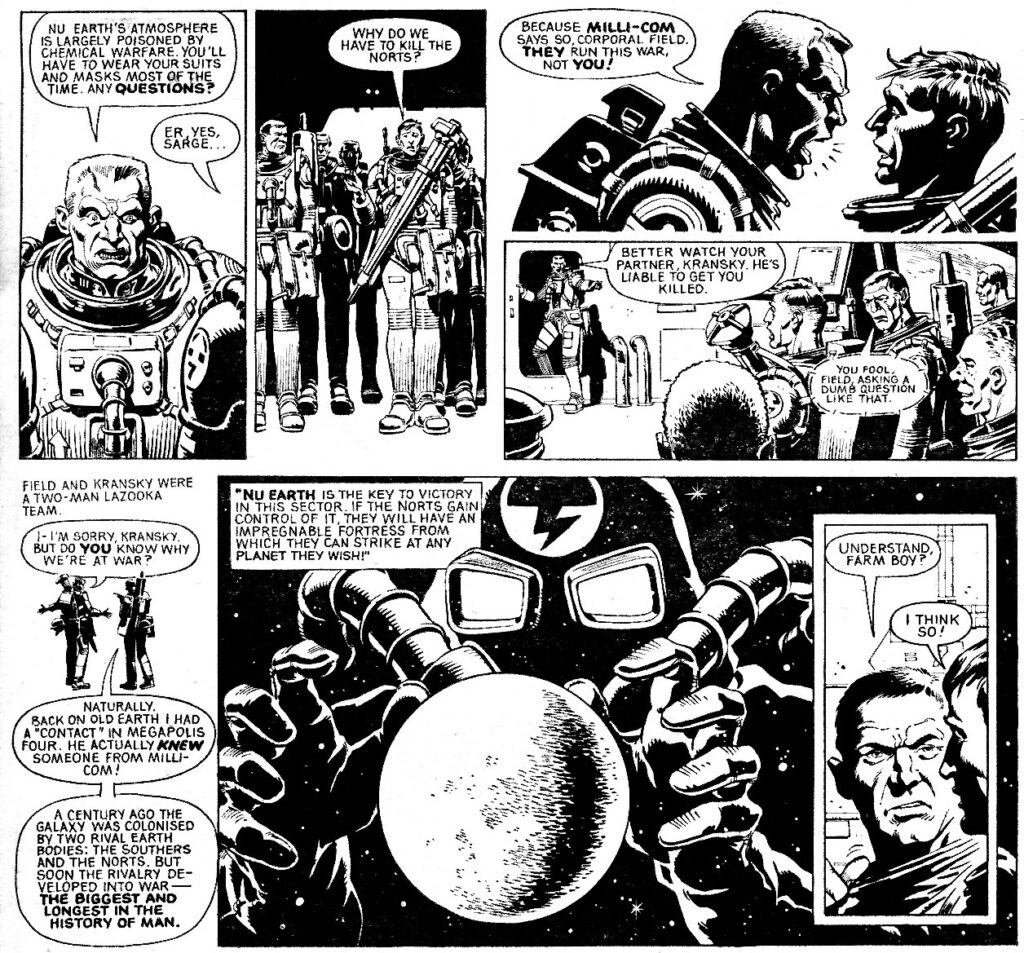

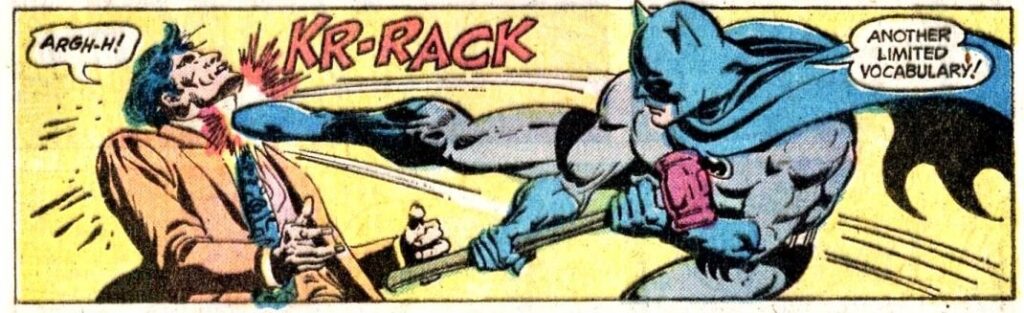

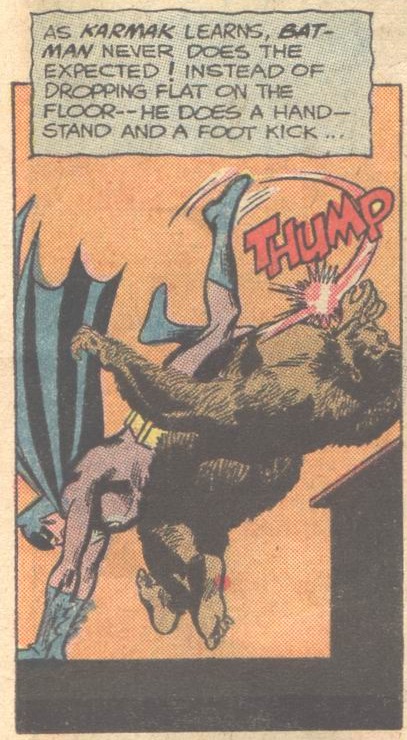

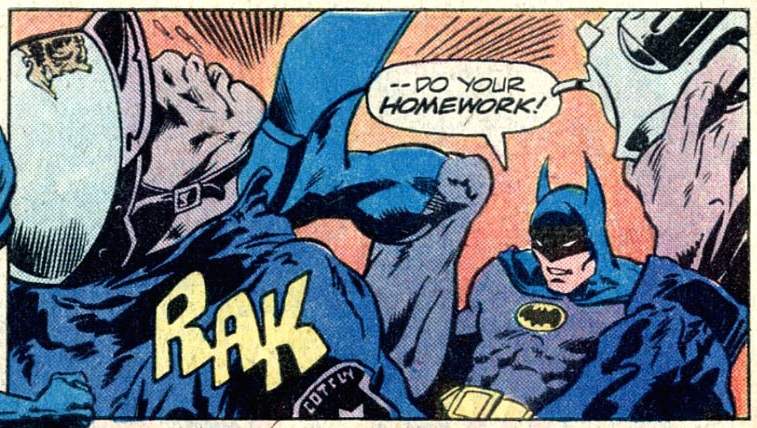

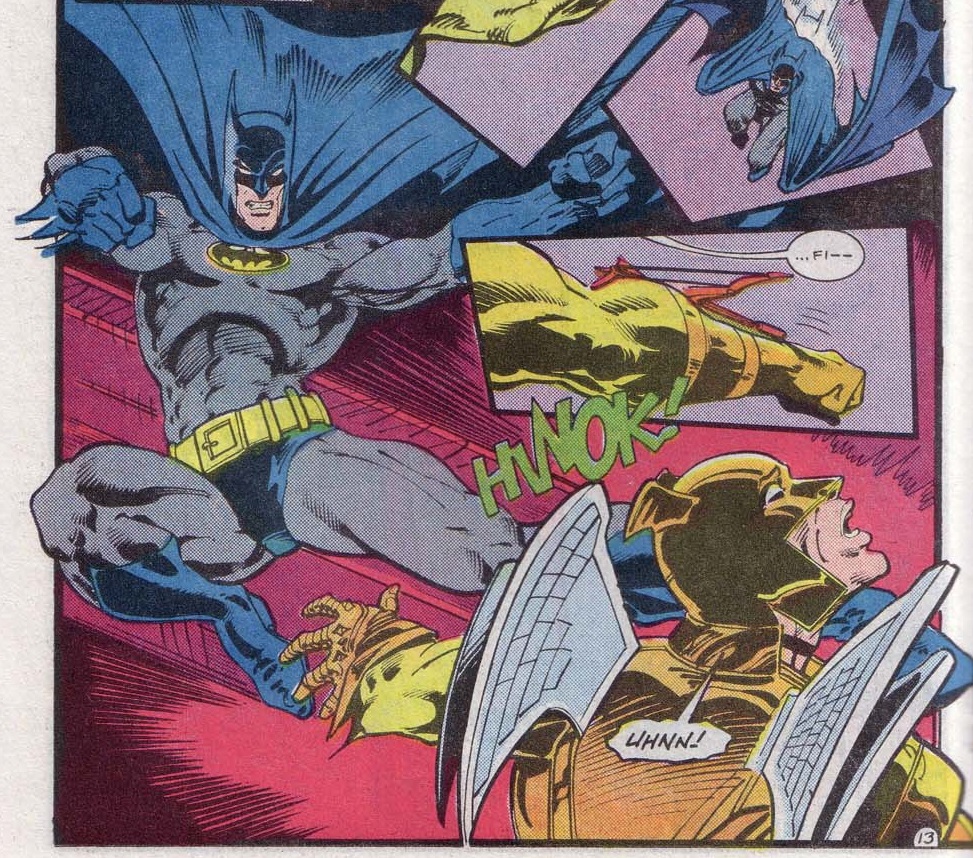

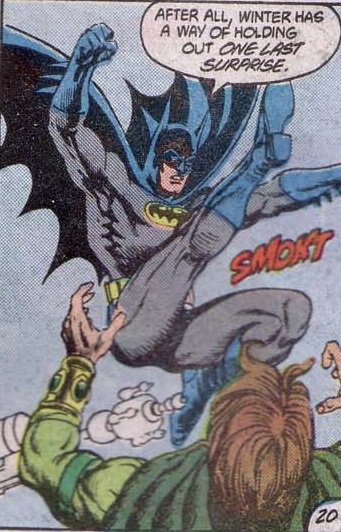

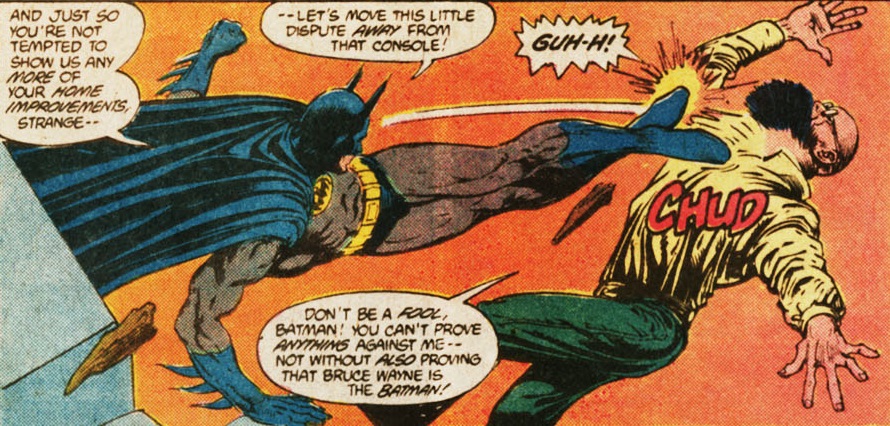

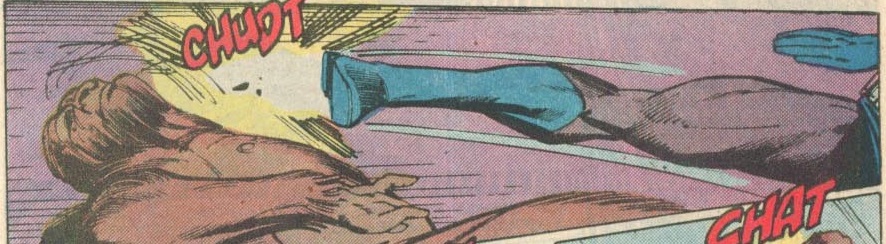

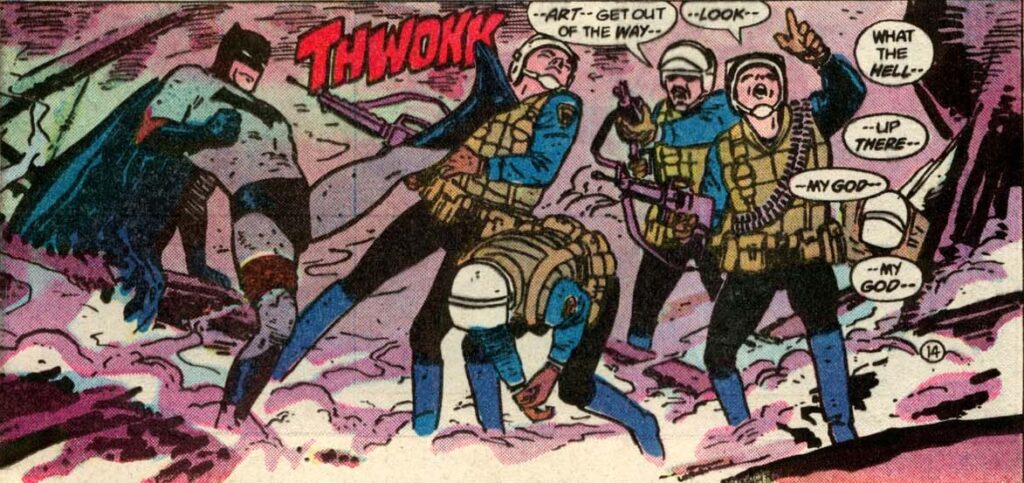

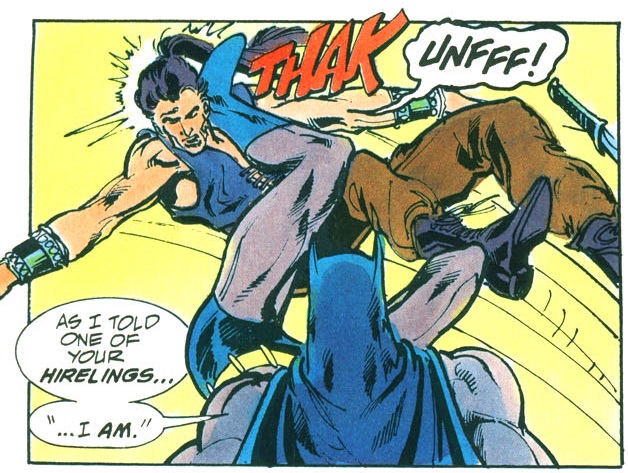

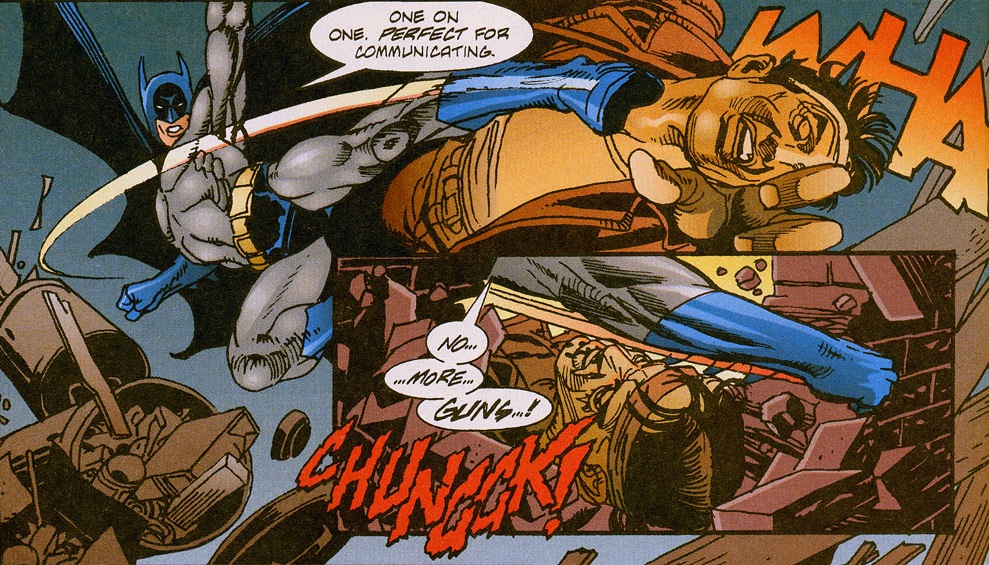

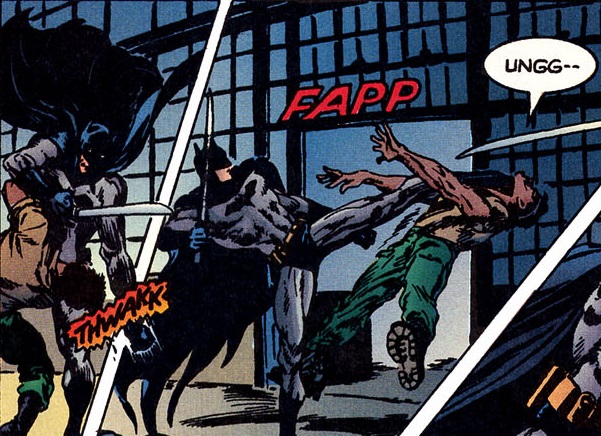

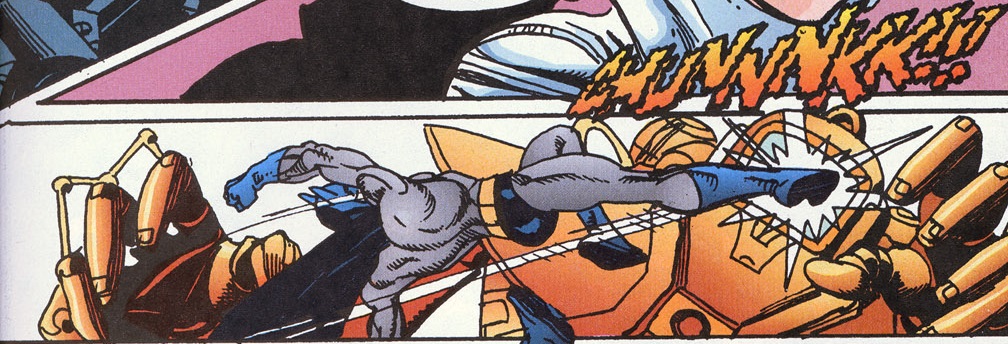

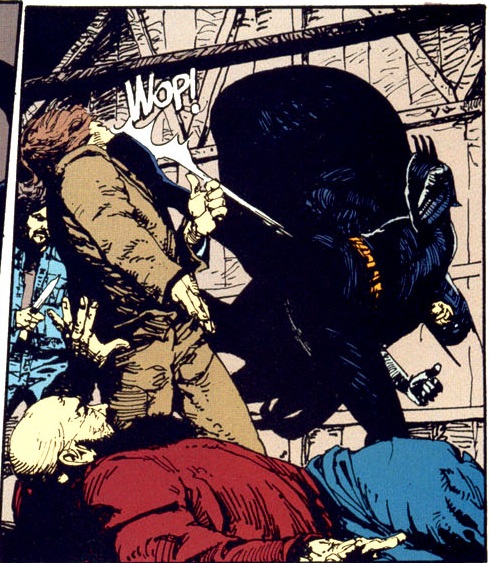

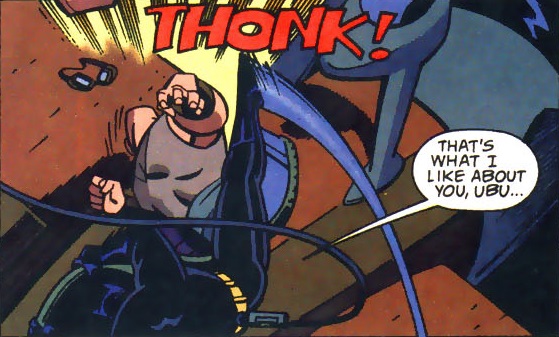

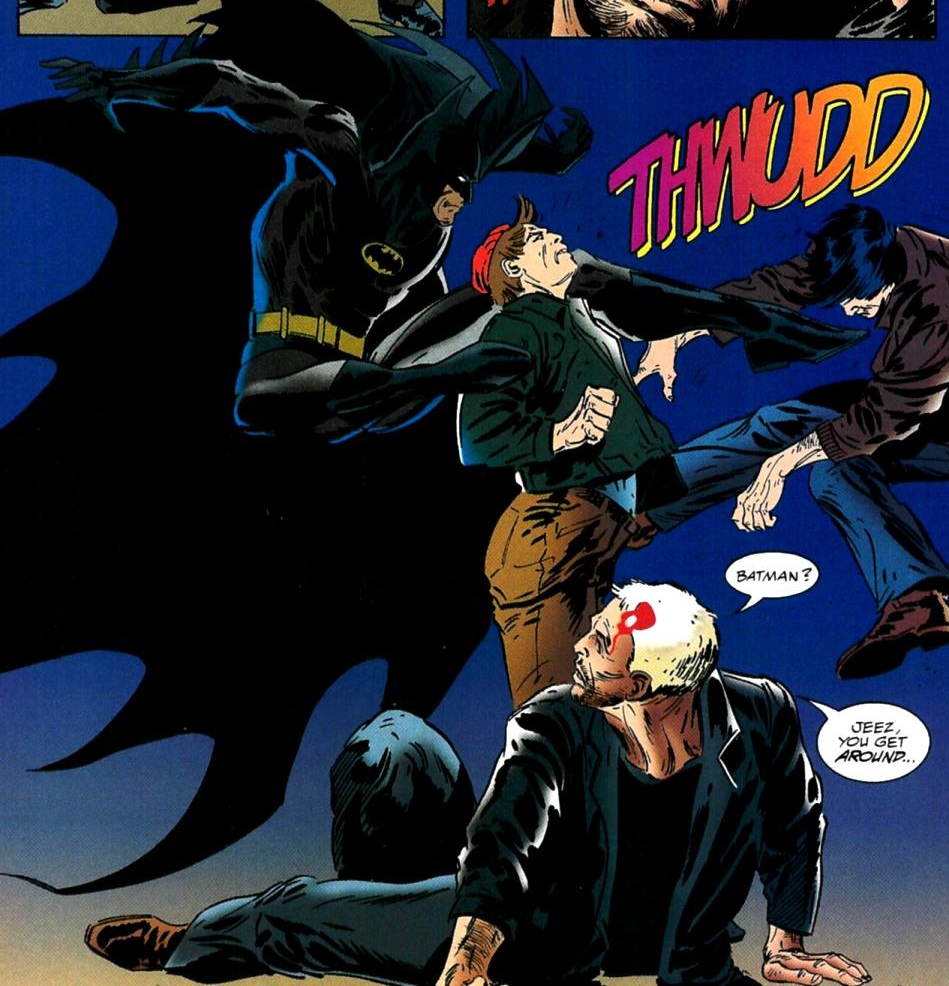

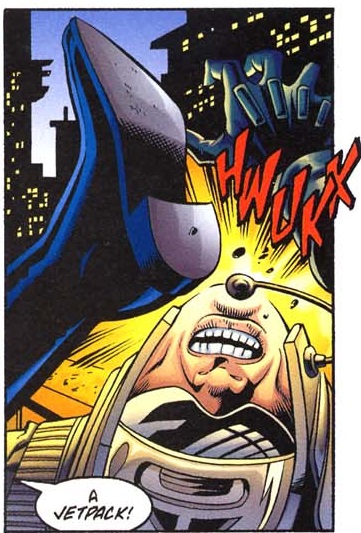

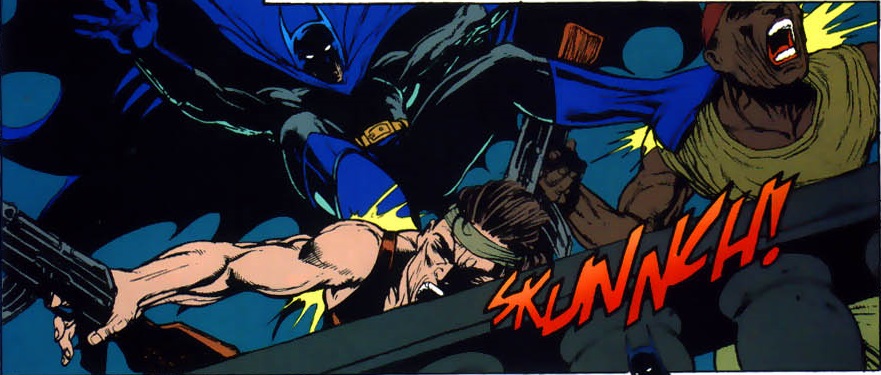

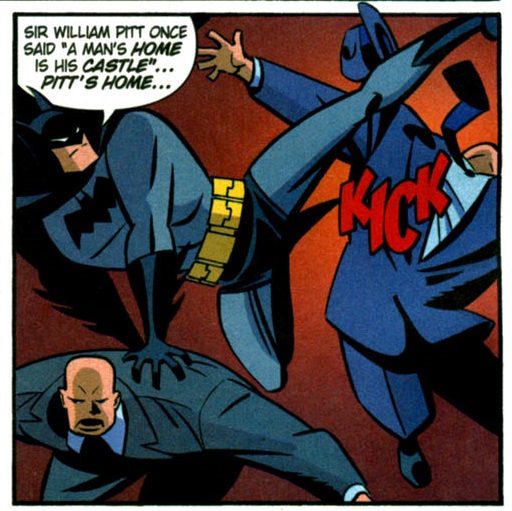

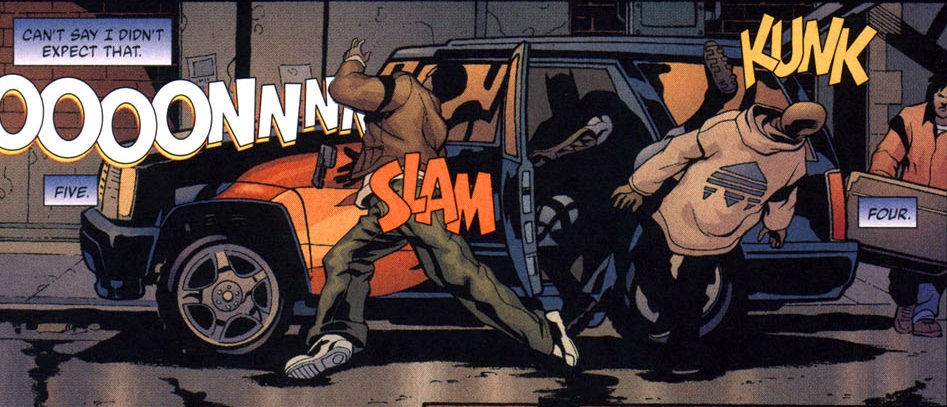

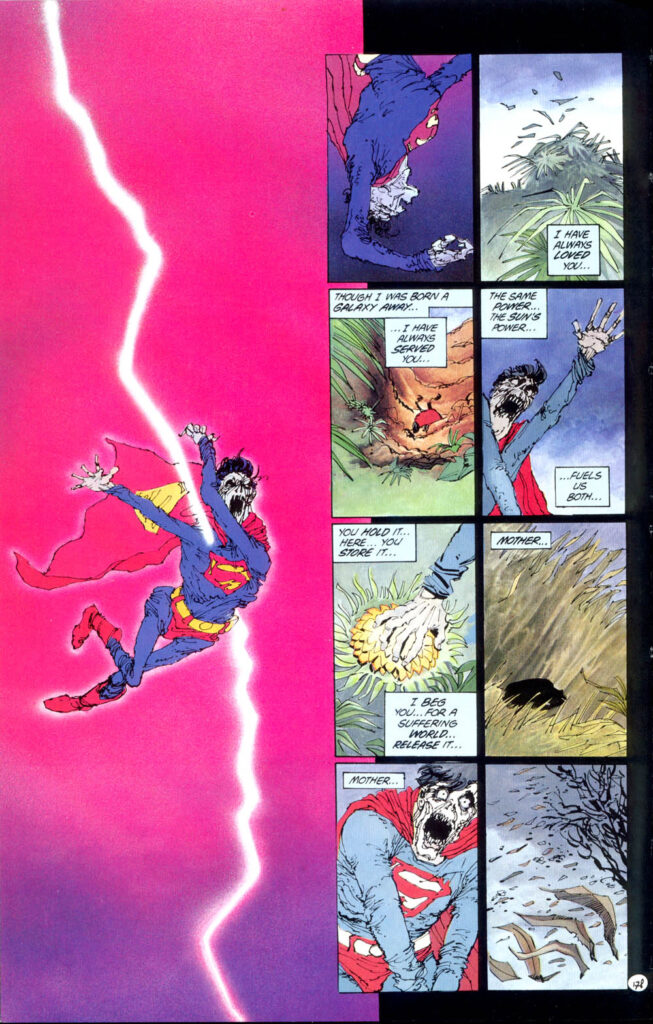

Visually, it’s hardly the most impressive Unknown Soldier comic. Killian Plunkett’s scratchy artwork and James Sinclair’s murky colors give the series a typical Vertigo look… I assume that’s part of the revisionist gesture, creating a deliberate contrast to earlier comics by making everything feel more somber and supposedly restrained (only the work of letterer Ellie DeVille occasionally evokes the potency of her predecessors).

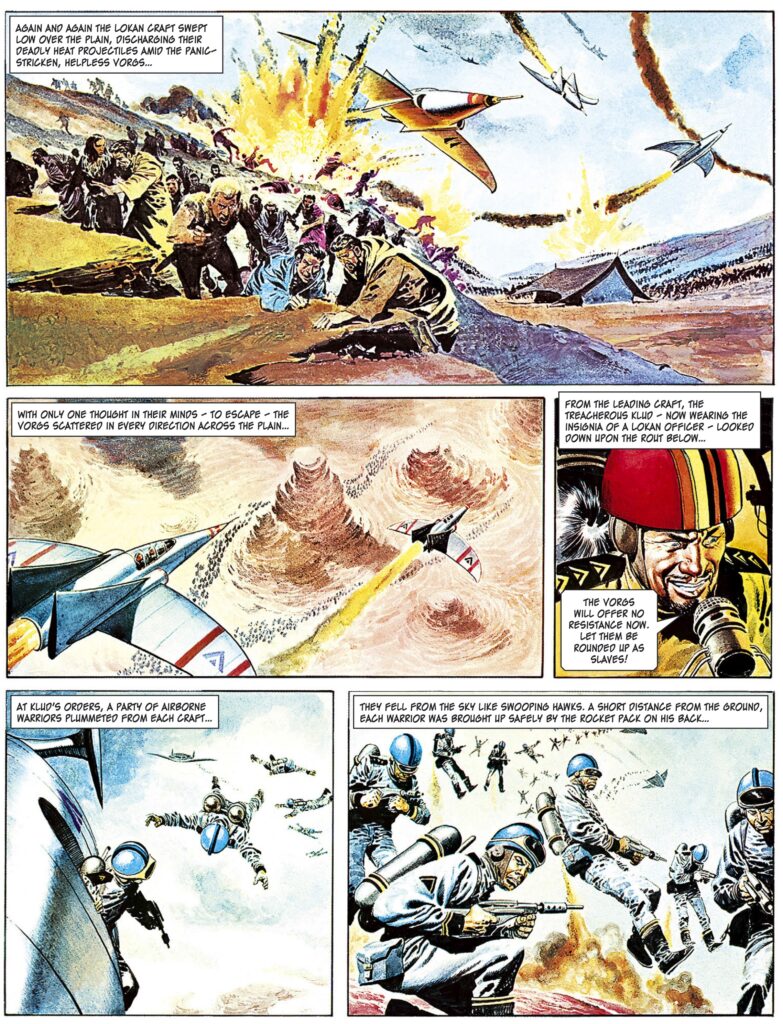

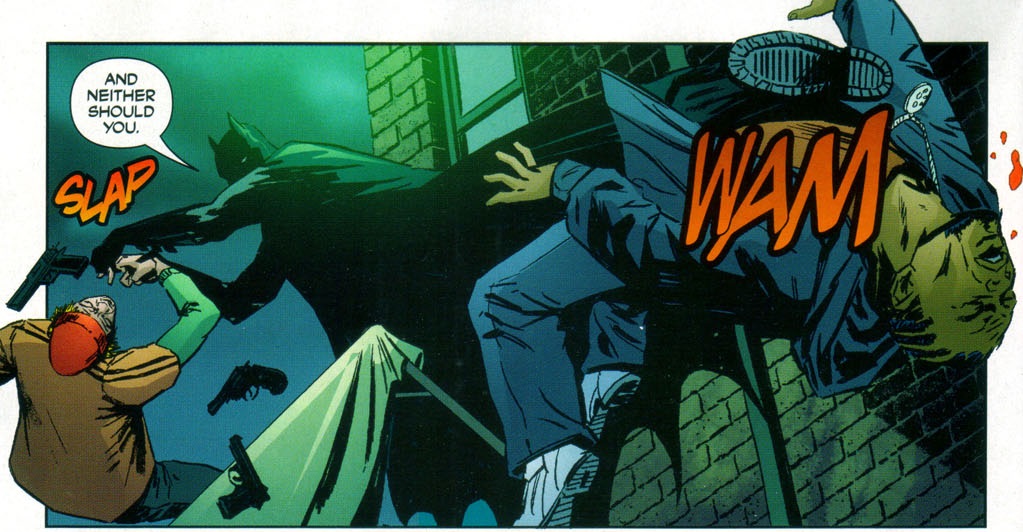

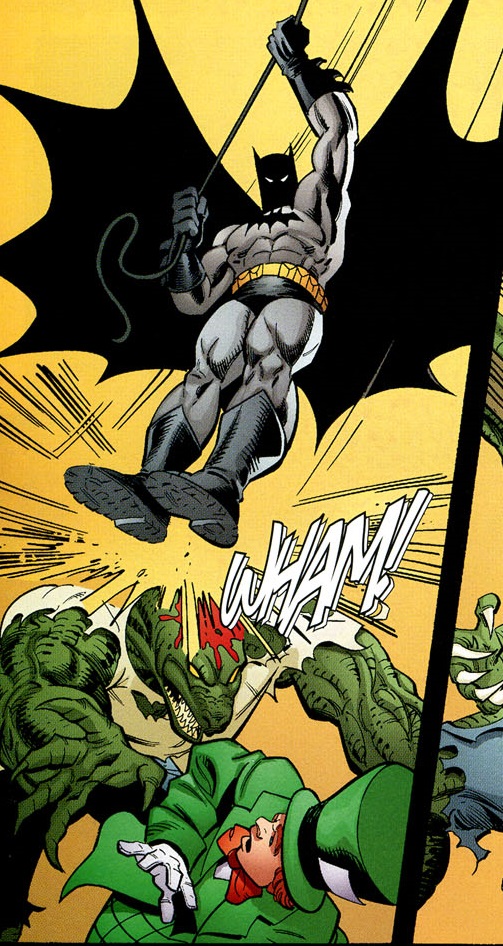

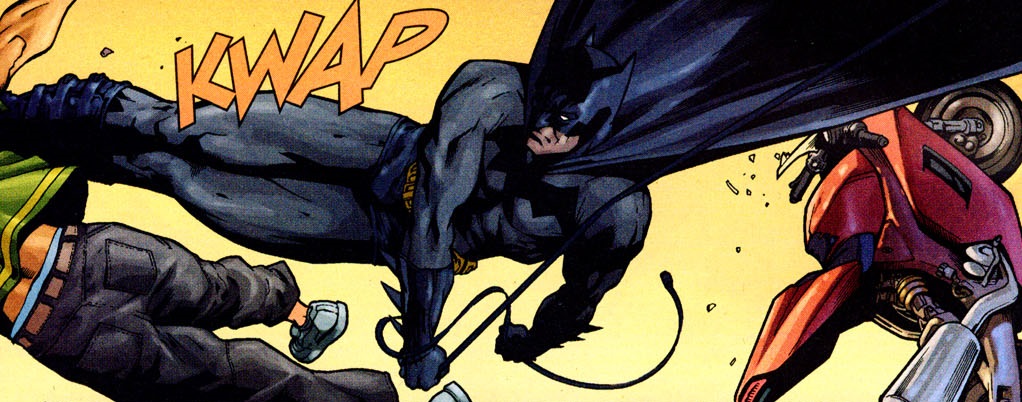

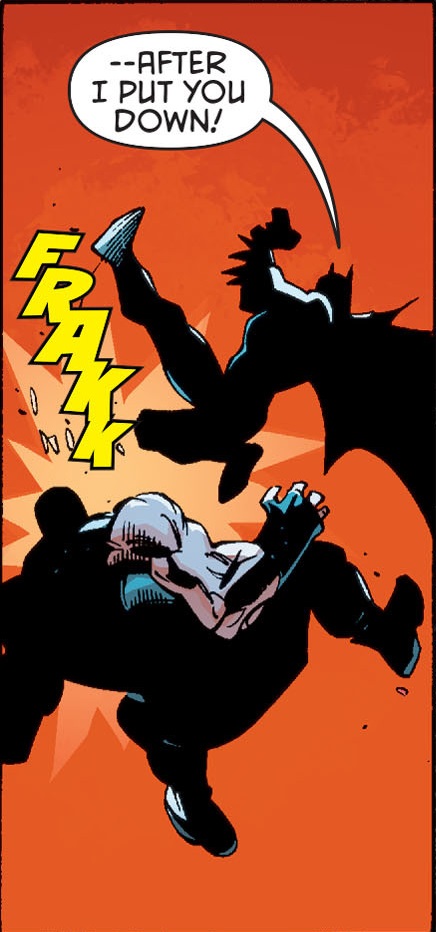

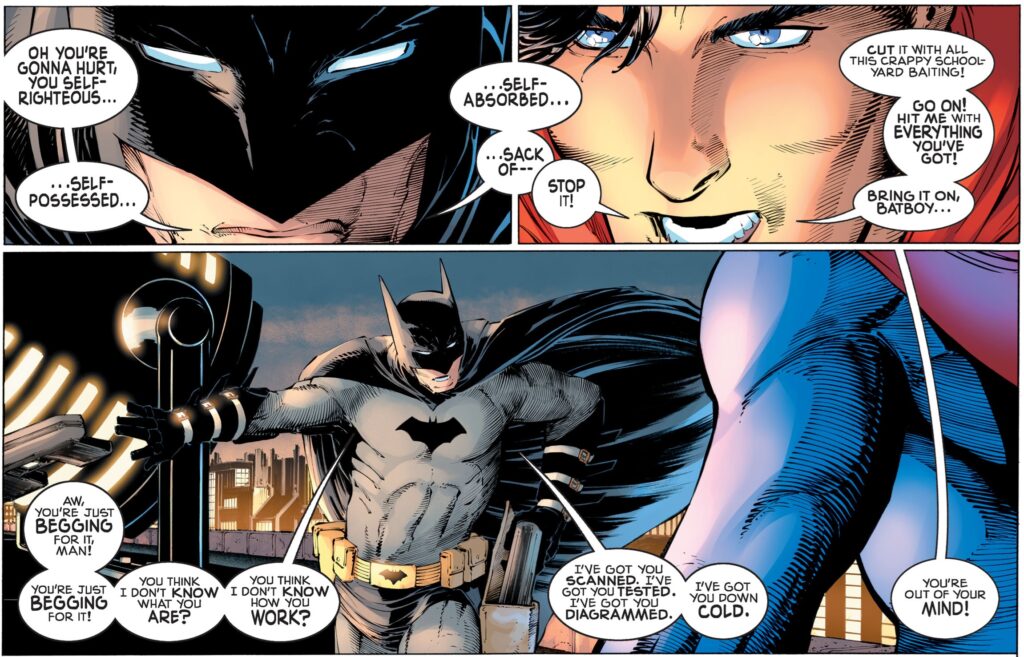

For an Ennis-written comic, the action is largely forgettable, although at least Plunkett makes the most out of the one chance he gets to show off his John Woo-esque skills:

Unknown Soldier (v3) #3

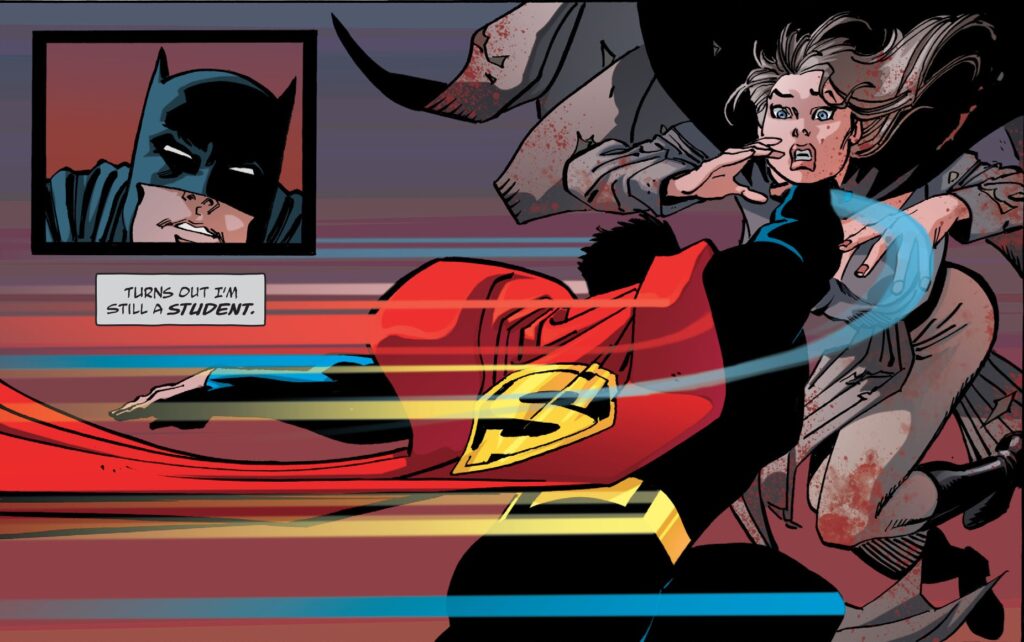

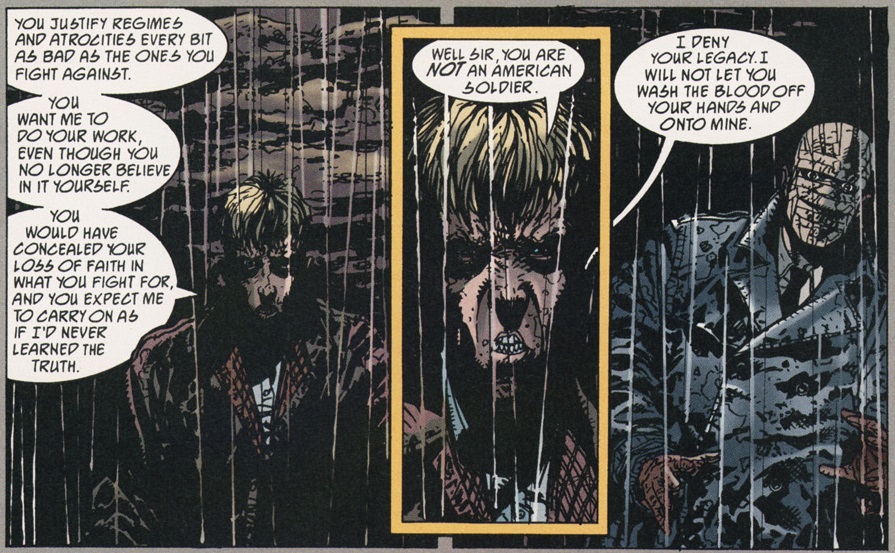

I guess it *is* a Garth Ennis book at the end of the day, and not an uninteresting one at that. It surely displays Ennis’ technical knack for dialogue and pacing, not to mention several of his work’s recurrent thematic motifs, including the perennial clash between idealists and hard-nosed pragmatists. Hell, this reinvention of the Unknown Soldier may even retroactively be seen as a (less comedic) trial run for Ennis’ subsequent reinvention of Nick Fury at Marvel, where he also took an established gung-ho WWII character and used him to explore the United States’ global military engagement during and after the Cold War.

That said, this was still a younger Ennis (in his mid-twenties at the time) writing during the Clinton era (when foreign policy was increasingly presented as ‘humanitarian intervention,’ as opposed to the more self-defensive/preemptive doctrine following 9/11), so his script seems particularly unambivalent about denouncing and condemning what the Unknown Soldier stands for. By taking such criticism farther than in any previous iteration of the series, ultimately we do get quite an original contribution to the character’s evolving saga…

Unknown Soldier (v3) #4