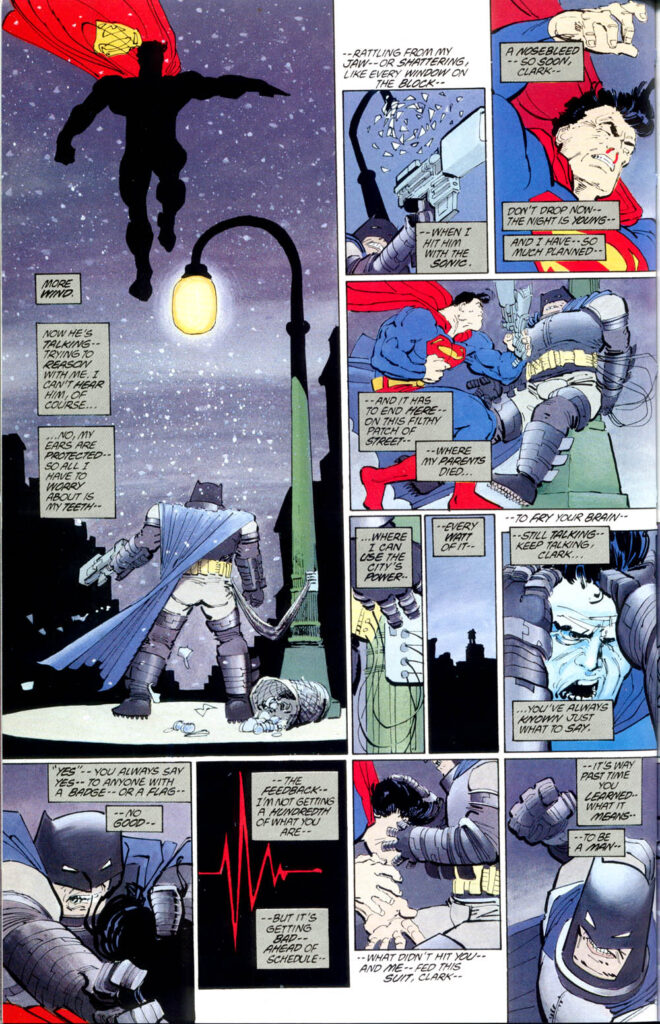

We’ve arrived at the end of Gotham Calling’s long-running Cold War cinema retrospective… And if you think depictions of the conflict were winding down in the final years, you’re in for a surprise. This is probably the bloodiest – and certainly the most testosterone-heavy – installment on our list!

In contrast to the kind of mature, experimental cinema of the 1960s and ‘70s, Reagan-era productions largely reduced the Cold War to teen-geared, over-the-top (if narratively conventional) popcorn blockbusters full of sound and fury, perhaps to compensate for the anti-climactic real-world denouement. What happened outside of fiction was in many ways mind-boggling, world-changing, and certainly fascinating (see, for example, Lea Ypi’s highly amusing and thought-provoking memoir Free, about seeing the transition in Albania through a young person’s eyes), but most popular films I know weren’t quite ready to imagine a new reality… and so, while the Cold War did not end in a bang after all, there were still plenty of explosions on the screen.

111. The Blob (USA, 1988)

This fun horror comedy about – you guessed it – a killer blob engages with the Cold War in a pretty direct way about two thirds of the way through, when we finally learn a bit more about the titular mysterious organism. Yet there is also a meta level: like much of eighties’ American culture, The Blob is a throwback to the fifties (it’s a remake of a 1958 B-movie), but by adding a satirical element – as well as a few echoes of The Crazies – the film ends up underlining the gap between the alleged consensus of the early Cold War (which Reagan sought to recapture) and the more cynical attitude of subsequent generations.

112. Miracle Mile (USA, 1988)

Because nuclear fears were a part of the zeitgeist practically until the very end, in the final years of the Cold War you could still find an urgent sense of existential anxiety in films like Miracle Mile, a quirky (yet very dark) indie one-crazy-night romcom/apocalyptic thriller about a shy trombone player trying to track down the girl of his dreams even as the world seems about to get blown away.

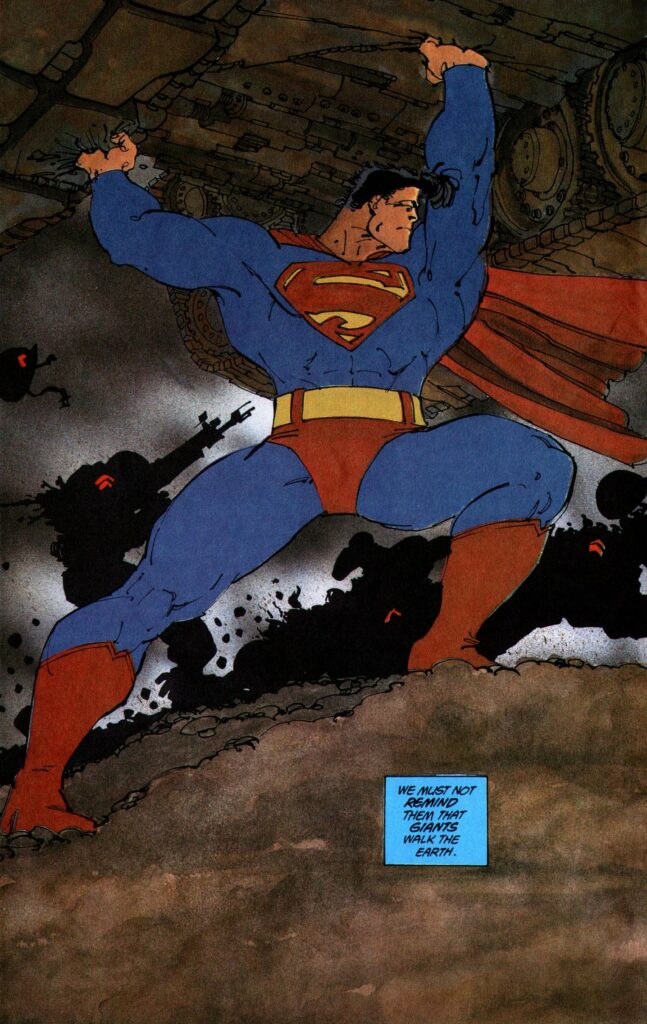

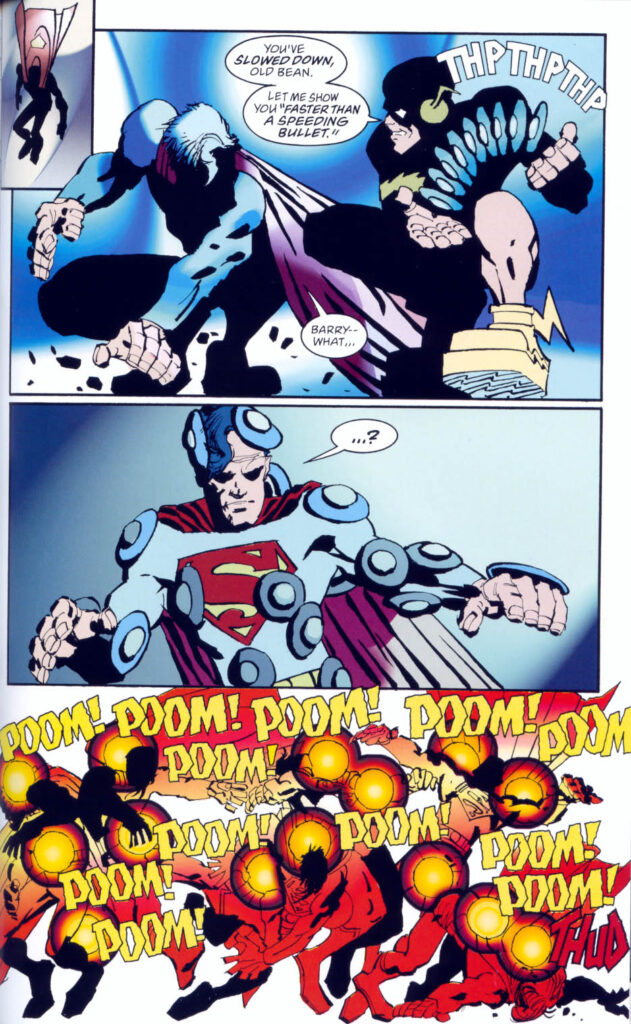

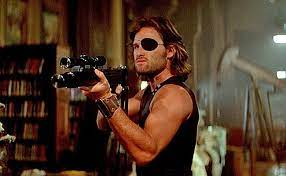

113. Rambo III (USA, 1988)

The one where one-man-army John Rambo fights alongside the Mujahedeen in Afghanistan! I had to include at least one of Sylvester Stallone’s iconic anti-Soviet trilogy – along with Rambo II and Rocky IV, this film is the epitome of the Reaganite macho action cinema mocked by the Dead Kennedys, although I still find it comparatively less campy than its immediate predecessor, perhaps because of all the gritty neo-western imagery, complete with a proto-cavalry climax in the desert… Fans may appreciate the subtle nods to the previous Rambo movies, even if an earlier monologue further subverts the spirit of First Blood (‘We didn’t make you this fighting machine. We just shifted away the rough edges.’). At least as many are bound to laugh, not just at the sheer over-the-topness of the whole thing (the laconic hero speaks almost exclusively in badass quips), but at how poorly its propaganda has aged (including the scene were a dead-eyed Stallone learns about the brave Afghans’ ‘holy war’). Plus, there is one more layer of irony: Rambo III was shot in Israel and it’s full of Israeli actors pretending to be Arabs fighting against invaders of their land.

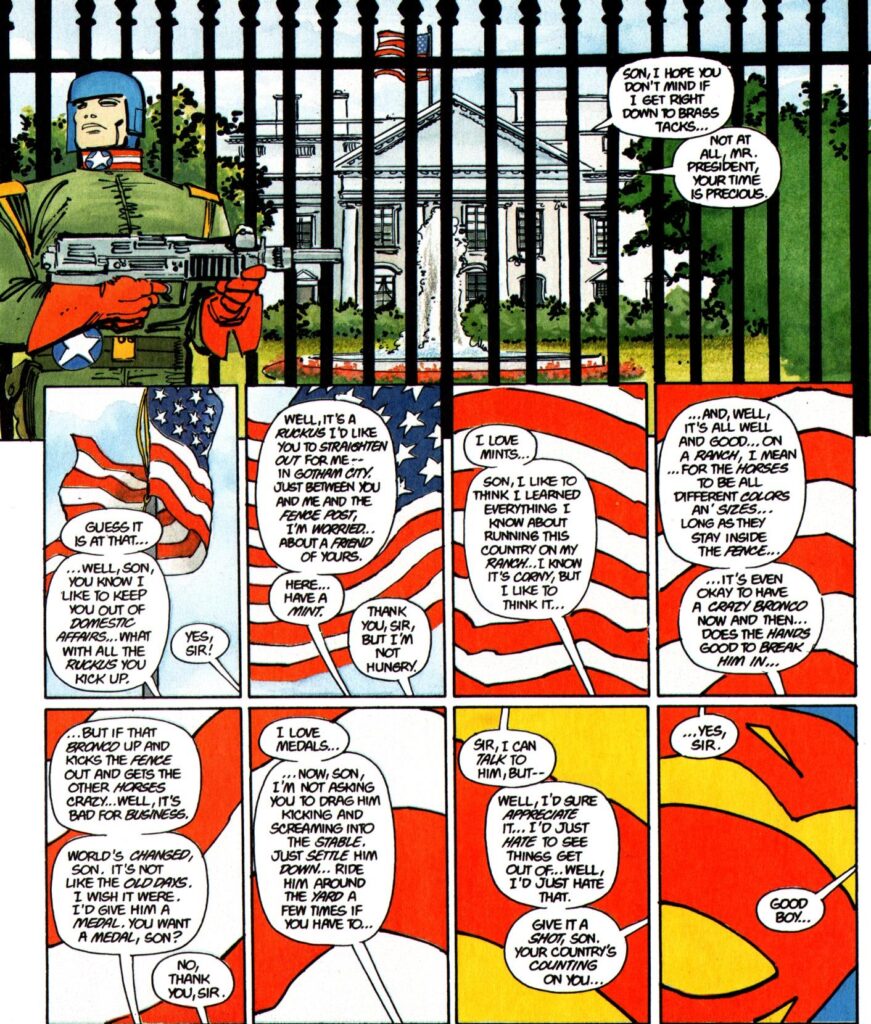

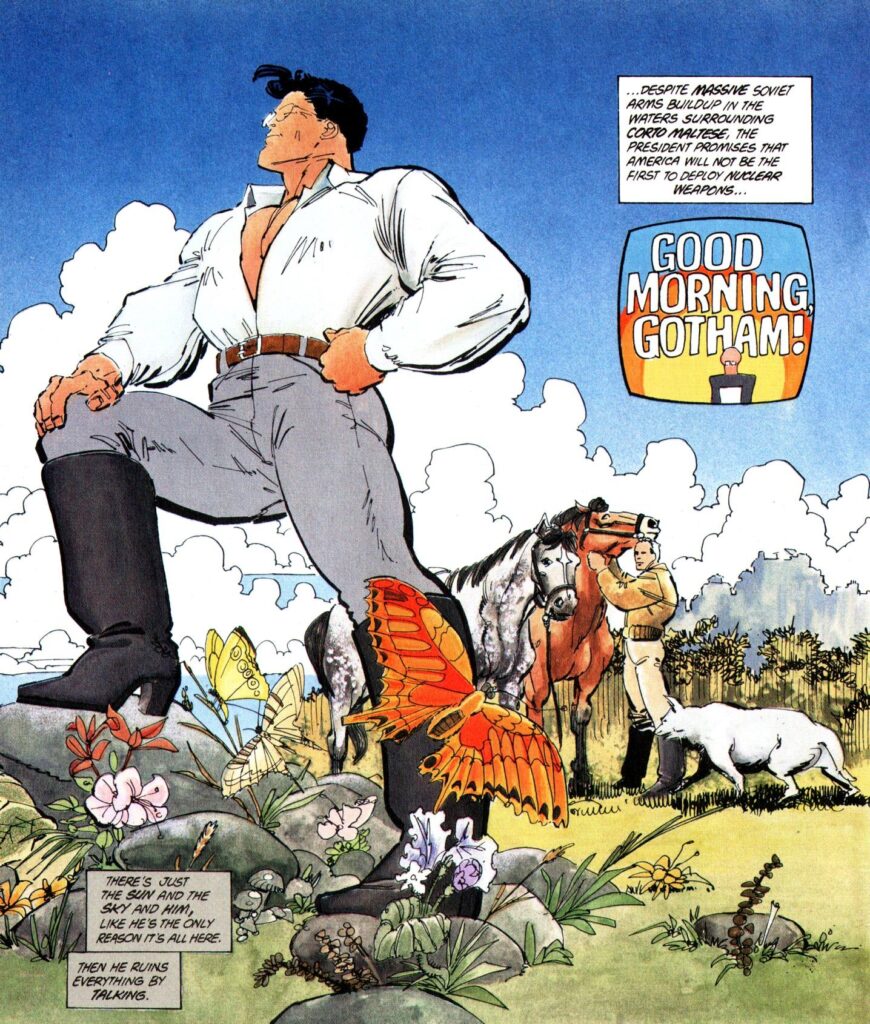

114. Red Heat (USA, 1988)

It’s perestroika as a buddy cop action comedy, with stoic Soviet officer Ivan Danko teaming up with a sleazy jerk from Chicago PD and the two learning to sort of begrudgingly respect each other despite their differences, much like the superpowers were doing during Mikhail Gorbachev’s leadership. That very specific moment of rapprochement is signaled not only by the fact that the film was partially shot on location in Moscow itself, but also by the decision to depict Schwarzenegger as a heroic embodiment of Soviet strength and honest conviction (as imagined by Americans) rather than as a defector (like in the next movie on this list). Indeed, while Red Heat is all about thick national stereotypes, the result practically feels like an inversion of Hollywood’s traditional propaganda: the United States are a dirty hellhole where cops envy the Soviets’ authoritarian methods (‘Do you know Miranda?’), openness to the West has mostly served to flood the USSR with cocaine, and Danko doesn’t fall in love with consumerism, Ninotchka-style, although he does get a lesson on Marxism from an African-American gang leader in a scene that has to be seen to be believed.

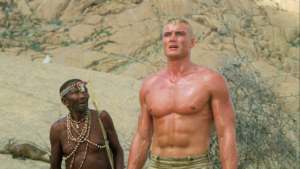

115. Red Scorpion (USA, 1988)

From the Congo Crisis to the Ogaden War, postcolonial Africa was certainly a key geopolitical battlefield, yet there aren’t many movies about it… One brazen exception is yet another exponent of the golden age of absurd macho bullshit: giving Rambo III a run for its money when it comes to warnography, this revisionist version of the Angolan Civil War pits pure-hearted African freedom fighters against sadistic Cuban occupiers. Ingeniously, Red Scorpion focuses on a Spetsnaz operative (the gigantic Dolph Lundgren, still in Rocky IV mode) who first pretends to desert and then truly deserts, so that he spends both the initial and the last stretch of the film massacring commies *and* we still get a classic ‘anti-authority conversion’ story out of it. Sure, above all this is an utterly tasteless piece of exhilarating exploitation (one of the characters, played by M. Emmet Walsh, even risks his life during an explosive chase scene to ensure there’s kickass music playing in the soundtrack, Baby Driver-style), but it’s hard to deny the film’s agenda, as it shamelessly reduces the MPLA to mere puppets, thus implicitly endorsing the support to UNITA provided by the Reagan administration and by South African troops… Indeed, the politics here are so comically grotesque – and so in-your-face – that it hardly comes as a shock that the production itself, shot in Namibia, broke the international boycott against apartheid South Africa.

116. Bullet in the Head (Hong Kong, 1990)

Maoist protesters, the Vietnam War, and the specter of the CIA have all shown up on this list before, but Bullett in the Head provides an original perspective, looking at them through the eyes of three friends from Hong Kong fighting their way through southeast Asia in the late 1960s. Don’t be fooled by the cheesy opening: this is a deliriously violent epic and, for my money, John Woo’s greatest masterpiece. (As far as I can tell, though, there is no connection to Rage Against the Machine’s awesome song that came out just a couple of years later.)

117. The Hunt for Red October (USA, 1990)

Set in 1984 (i.e. pre-Gorbachev), this submarine spy thriller shows Hollywood trying to hold on to old narratives in a rapidly changing world. Still, as far as spectacle goes, The Hunt for Red October does the job: John McTiernan, who feels at home directing spatially-defined narratives where he methodically moves the pieces around, confidently interweaves sub battles and diplomatic maneuvers, piling twists on top of twists.

118. Robot Jox (USA, 1990)

A delightfully cheesy update of The 10th Victim-style strand of futuristic narratives where nuclear confrontation is superseded by other forms of competition: in this case, international disputes are resolved by one-on-one combat between mecha fighting machines (rendered in adorable stop-motion animation). Suitably for this closing era, Robot Jox feels like you’re watching children of the Cold War playing with their toys and inherited stereotypes (from the cruel, Russian-sounding antagonist to the simplistic espionage subplot), reproducing the conflict’s cycle of one-upmanship while also making it seem childish and ridiculous. I wonder if the final shot is a ‘fuck you’ to the opening of Rocky IV…

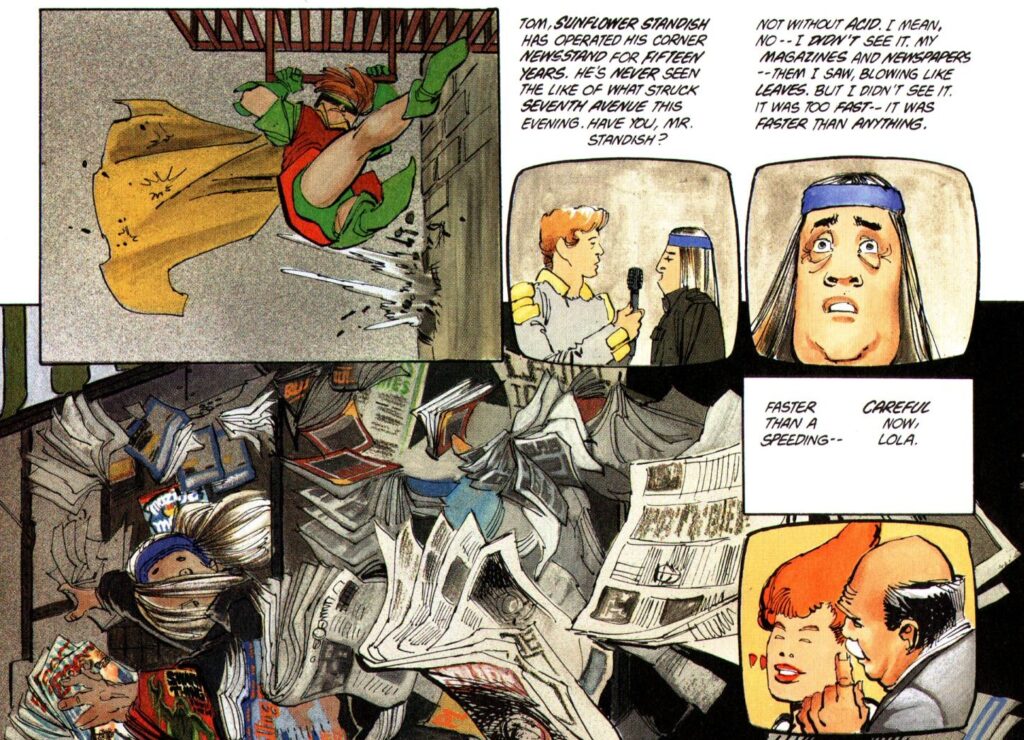

119. Terminator 2: Judgment Day (USA, 1991)

In isolation, 1984’s awesome sci-fi/horror/action classic The Terminator did not add much to existing Cold War narratives (its spin on familiar fears about AI-based defense programs was that this time the result was not only atomic war, but the rise of human-enslaving machines). When taken in conjunction with its first sequel, though, we get one of the great meta-texts about the Cold War’s endgame: while the original has a foreboding sense of imminent doom (personified as a badass time-travelling cyborg killer) that seems quite appropriate to the rising tension in the early Reagan years, Terminator 2 is ultimately about moving on from nuclear nightmares towards an open-ended future. So, yes, James Cameron addressed the Cold War more directly in The Abyss (especially in the extended version), but T2 is the perfect coda to this cinematic journey.

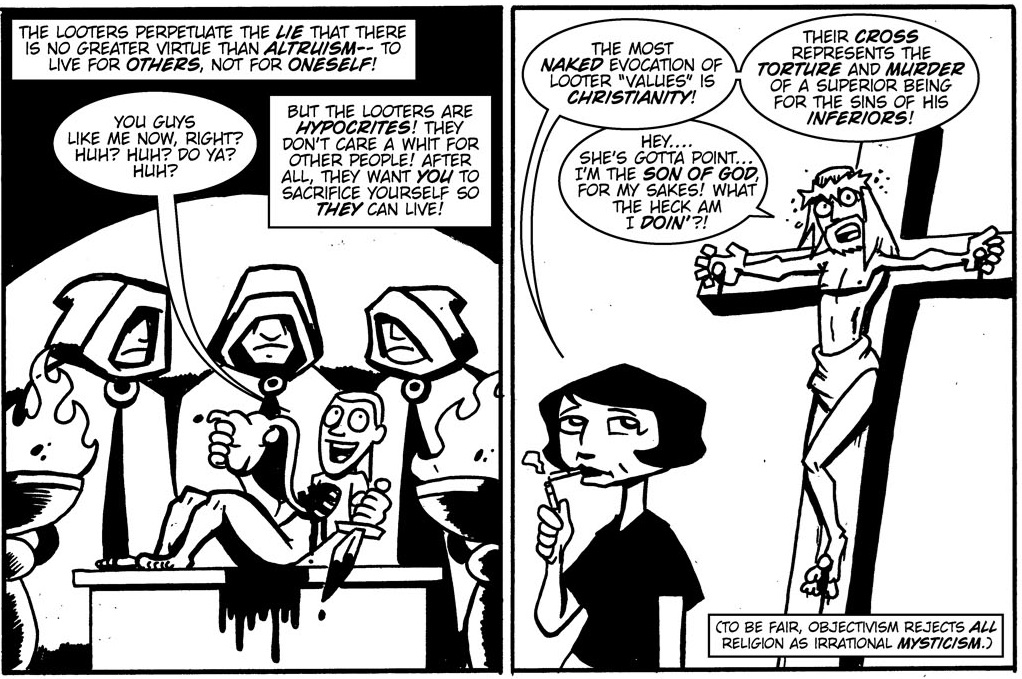

120. Tribulations 99: Alien Anomalies Under America (USA, 1991)

Tribulations 99 is surely the weirdest damn film on this entire list, but I can’t think of a more suited endpoint than a trippy collage of footage from old movies documenting an alternative history of the Cold War in Latin America that stitches real-world events (from the coup in Guatemala prompted by the United Fruit Company all the way to the invasion of Panama) with all sorts of conspiracy theories, thus recognizably framing the Red Menace in a continuum with tales of flying saucers and lizard people. I think of it as a prelude to The Department of Truth.