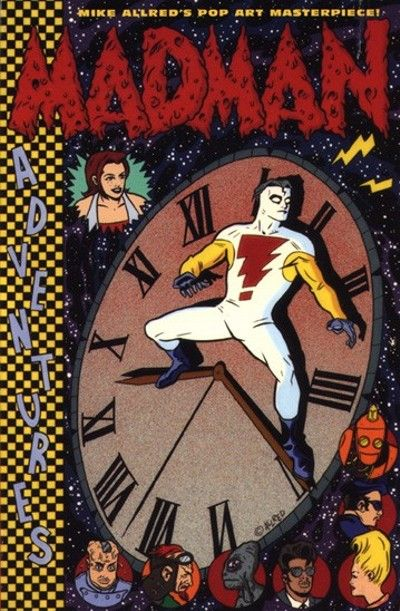

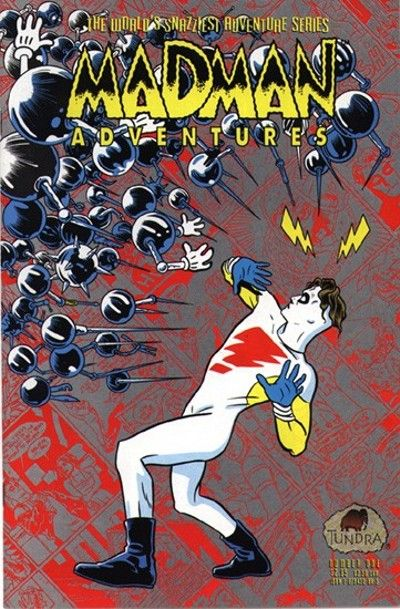

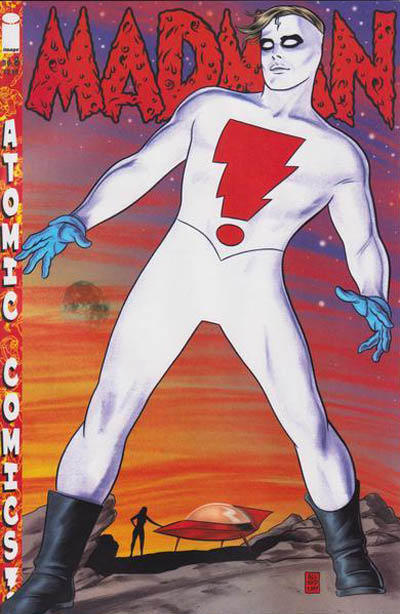

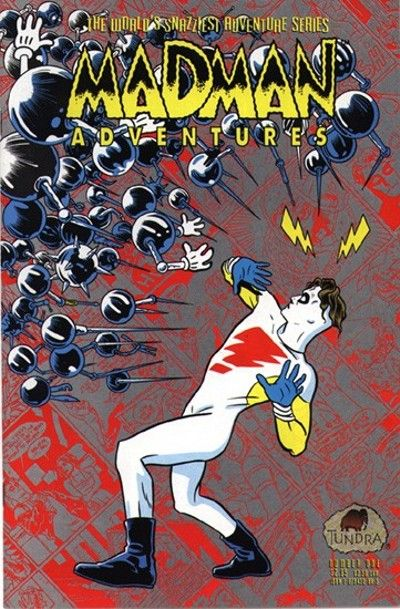

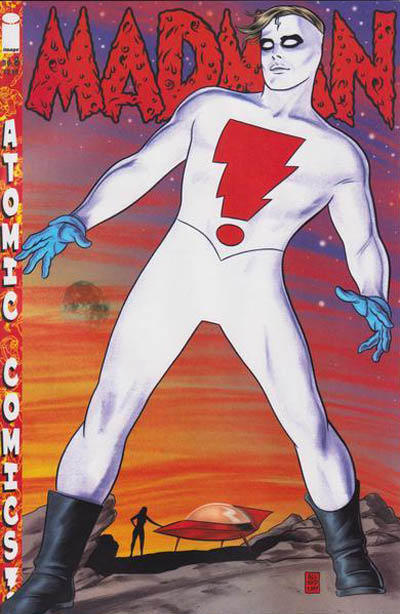

Today’s reminder that comic books can be awesome is a tribute to Mike and Laura Allred, who have perfected a mix of pop art and superheroes in their Madman comics:

Today’s reminder that comic books can be awesome is a tribute to Mike and Laura Allred, who have perfected a mix of pop art and superheroes in their Madman comics:

Welcome back to Gotham Calling’s ongoing list of notable films that gave an audiovisual expression to the Cold War (previous installments here and here). This time around, many of my choices are less explicit, as by the mid-1950s sci-fi horror became one of the key genres to tap into growing nuclear panic (especially following the testing of the powerful H-bomb).

That said, as the Cold War expanded geographically, you also get increasingly different settings – and different national cinemas filming the conflict’s impact from a more personal, close-to-the-ground perspective. The movies I selected this time, apart from being interesting on their own, are also meant to illustrate this wider contrast.

21. Godzilla (Japan, 1954)

Last time, we finished with Animal Farm – and this time we’ll start with a couple of very different animal-based allegories (‘animallegories’). The most influential monster picture of all time posits a blatant indictment of nuclear weapons. The original Godzilla is so moody (not least because of the music), downbeat (despite the cathartic appeal of destruction), and disturbing (if you look at it from the perspective of then-recent Japanese traumas) that you wouldn’t have expected this somber horrorfest to spur a franchise with such kid-friendly connotations.

22. Them! (USA, 1954)

In this Hollywood contribution to the ‘creature feature’ subgenre the symbolism is less straightforward, reflecting the double fear of homegrown radiation and of attacks on domestic soil by an enemy that cannot be reasoned with… and which can only be fought if all national institutions play their part. I’ve previously expressed my fondness for Them! here.

23. I Live in Fear (Japan, 1955)

A Tokyo businessman is so fearful of the hydrogen bomb that he tries to move all of his family (including a couple of mistresses and illegitimate children) to Brazil. I Live in Fear offers an intriguing snapshot of 1950s’ Japan (rather different from Godzilla!), courtesy of Akira Kurosawa’s restless camera and mise-en-scène…

24. Kiss Me Deadly (USA, 1955)

Another recurring recommendation in this blog… Loosely adapting a hardboiled detective novel by Mickey Spillane, Kiss Me Deadly both subverts the source material and injects a whole new conspiracy angle that firmly ties the story into the nuclear era.

25. Piagol (South Korea, 1955)

Refusing to accept the 1953 armistice, a North Korean unit engages in a mountain-based guerrilla and gradually self-destructs in this very gritty war movie, whose terse style and ingenious cinematography make the most out of the rugged landscape. Piagol would be interesting enough as a twisted South Korean depiction of the recent (and, technically, ongoing) enemy… What makes it an even more stimulating historical object is the fact that the film was initially banned because the Seoul authorities considered that it overly humanized the communists, so the director had to add a patriotic flag to the final shot to get it approved.

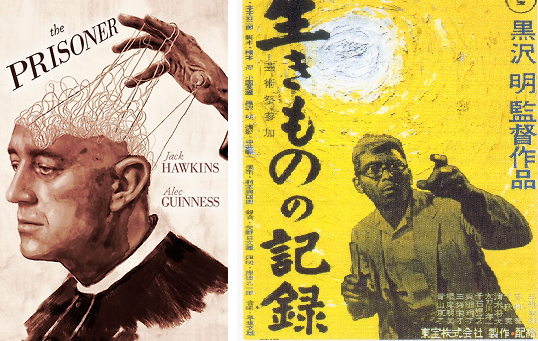

26. The Prisoner (UK, 1955)

The Prisoner delivers a cerebral, Kafkaesque nightmare in the form an unnamed dictatorship where a cardinal accused of treason has an enthralling battle of wills against his interrogator. While touching on key points of Western indictments of the Eastern European regimes (political persecution, psychological torture, anti-clericalism), the film actually turns into a smart character study, not least because of Alec Guinness’ nuanced performance.

27. Sky Without Stars (West Germany, 1955)

Sky Without Stars pulls at your heartstrings through a love story in divided Germany, as seen from the West. It works powerfully on both literal and allegorical levels: more than the communist system itself, the main source of (individual and national) tragedy are all the different borders keeping people apart. Manipulative, yet affecting.

28. A Berlin Romance (East Germany, 1956)

A Berlin Romance pulls at your heartstrings through a love story in divided Germany, as seen from the East. With its young protagonists searching for their place in the world, whether in West or in East Berlin, this is arguably the most sensitive of a brief surge of productions – made in the context of de-Stalinization – observing and even criticizing the GDR’s shortcomings (albeit still expressing faith in socialism). Manipulative, yet affecting.

29. China Gate (USA, 1957)

Linking up Asia’s conflicts, this bonkers adventure has veterans from the Korean War join the French Foreign Legion in 1954 Indochina in order to keep up the good fight – with the help of a sultry smuggler called Lucky Legs. China Gate is so brazenly anti-communist, colonialist, and committed to domino theory that it has to be seen to be believed (the opening narration alone is an entire treaty!), its melancholic ending coming across as even more tragic once you consider what lays ahead. That said, this utterly glorious mess is yet another gem written and directed by Sam Fuller, whose visceral style means that every shot is bombastic and, every time you think you have the film figured out, it’s bound to surprise you in some way (like when Nat King Cole starts singing the movie’s theme song among a village’s ruins, or when Lee Van Cleef shows up as a loquacious schoolteacher-turned-warlord praising Ho Chi Minh and dreaming of working in Moscow…). Seriously, this could be a companion piece to the first arc of Fury MAX: My War Gone By! Plus, like many of Fuller’s pictures, it revolves around an idiosyncratic examination of racism.

30. Enemy from Space, aka Quatermass 2 (UK, 1957)

Like giant monsters, 1950s’ extraterrestrial threats (especially depersonalization narratives) are often read as a quintessential manifestation of Cold War anxieties on screen, so I had to include at least one entry into this emblematic cycle. My pick is this sequel to the – also pretty awesome – cult classic The Creeping Unknown (aka The Quatermass Xperiment). Enemy from Space revisits – and expands – the original’s premise about an alien menace, now with an added conspiracy threat that puts a very British spin on Invasion of the Body Snatchers: as argued by Matthew Jones, if US sci-fi produced metaphors about communism infiltrating small communities, here the villains seem to represent the mole-ridden UK establishment, which in the climax is pitted against a mobilized working class.

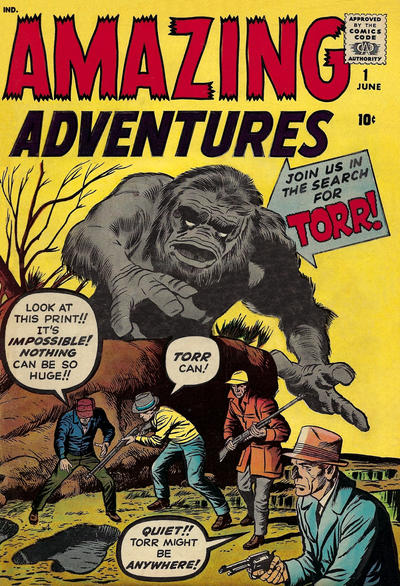

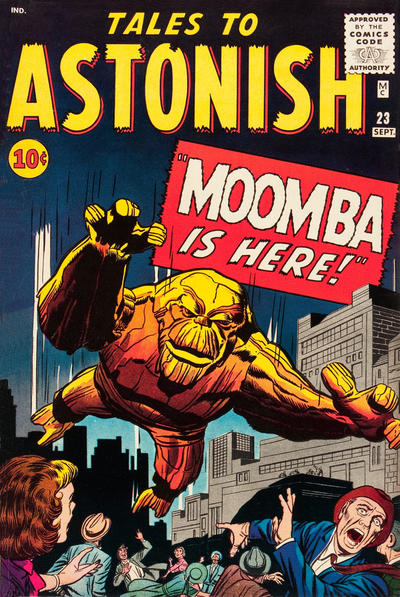

As the world spirals further into a hellhole of wars, refugees, and climate disasters, I take small pleasures where I can find them… This week’s reminder that comics can be awesome is yet another tribute to Jack Kirby, who spent much of his career drawing huge monsters with silly names:

Batman comics have borrowed and blended different storytelling traditions from the get-go, but never was this more apparent than in the Silver Age, when writers constantly pillaged all sorts of books, films, and trends for inspiration (as opposed to more recent comics, which mostly pillage other comics).

With that in mind, today I want to zoom in on ‘Zero Hour for Earth!’ (Batman #167, cover-dated November 1964), penned by Bill Finger (one of the original co-creators of the Dark Knight), drawn by Sheldon Moldoff (and not by Batman’s other co-creator, Bob Kane, even though he signed the work), and inked by Joe Giella (the defining inker of the New Look era).

Back then, Batman issues used to feature at least a couple of tales, but this yarn takes up the full issue and boy does Finger pull out all the stops… Anticipating the blockbuster-like approach Bob Haney would later develop in The Brave and the Bold, this is a relentless read where, after watching the death of an Interpol agent, the Dynamic Duo chase both an international crime syndicate called Hydra *and* an unrelated megalomaniac villain trying to start World War III.

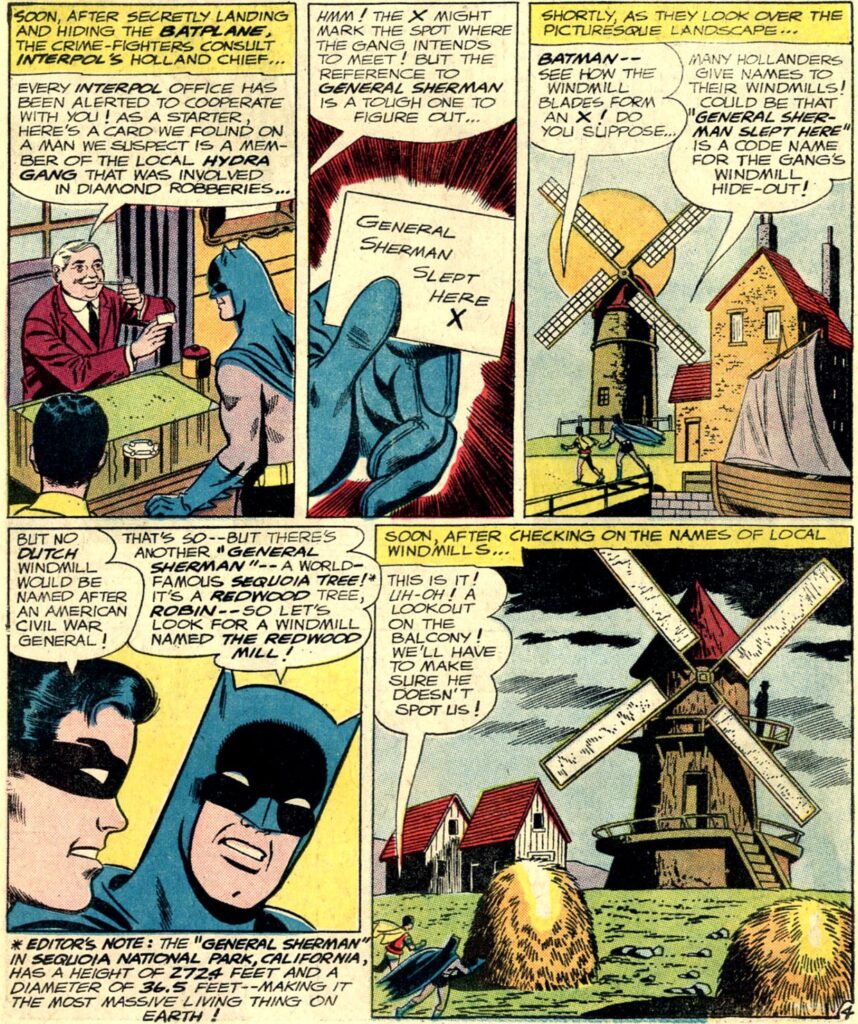

Part of Finger’s strategy to keep the story moving is to constantly adjust what kind of story it is. At first, we get the classic Batman & Robin formula in which the characters have to decipher puzzle-like clues that lead them on a breadcrumb trail from one place to another. You even get one of those ‘editor’s notes’ giving readers further interesting information, unrelated to the plot…

Who said comics aren’t educational?

So, early on, despite the foreign setting, ‘Zero Hour for Earth!’ still reads like a fairly conventional superhero comic. The fact that the villainous organization is called Hydra – a name that sounds evil and goes back to ancient mythology as filtered by pop culture – is a typical comic-book move (Marvel introduced its own villainous organization called Hydra a year later). It also allows Batman to utter this great line: ‘I intend to become a modern-day Hercules – and put an end to the hydra of crime!’

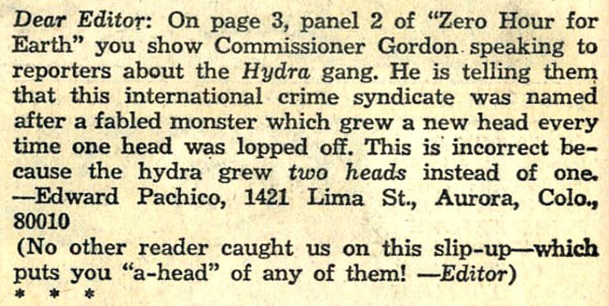

Then again, as pointed out by reader Edward Pachico on the letters’ page a few issues later, nobody appears to have given the reference more than a superficial thought… But that’s ok, because this provides editor Julie Schwarz with the chance to pun about it:

Batman #170

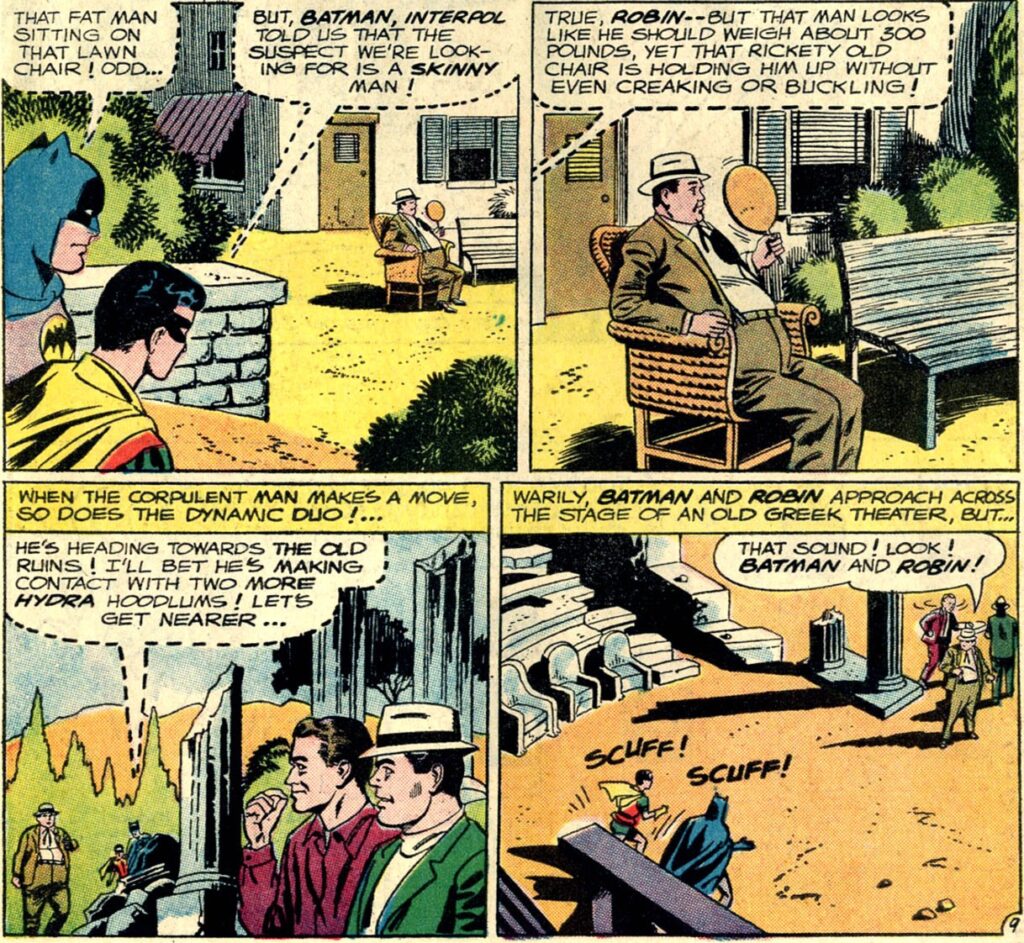

To be sure, when you’re dealing with the classic Dynamic Duo formula, you can often draw a straight line back to old-school detective fiction. While solving pre-set clues (usually requiring knowledge of random encyclopedic factoids and word-association skills) makes Batman cases feel like children’s games, our hero also gets to stake his claim as World’s Greatest Detective by applying observational and deductive reasoning throughout the story.

Passages like the one below aren’t particularly sophisticated (Bill Finger is no Conan Doyle or Ellery Queen), but the sheer recurrence of such tiny bits helps sell the cool idea that the Caped Crusader is always switched on and efficiently interpreting the world around him with detail and insight…

The fact that the two sequences I’ve shown you so far are set in the Netherlands and in Greece, respectively, should give you a hint about the other type of story woven into the narrative. In addition to everything else, ‘Zero Hour for Earth!’ is a tale of international intrigue reminiscent, to some degree, of those old Hitchcock thrillers where local landmarks were prominently integrated into set pieces (including Dutch windmills in Foreign Correspondent, which is probably the film closest in spirit to this comic).

The genre hybrid doesn’t feel awkward at all. Elements of cloak & dagger – such as secret codes and disguises – seem right at home in the playful reality of the Caped Crusader, where hiding a message by punching it in braille into the rim of a hat isn’t more preposterous than any of Batman’s usual gimmicks.

I swear the scene above is ripped straight from an old movie I’ve seen, but I can’t quite place it at the moment… Although the exotic dancer/secret agent figure is surely a nod to Mata Hari on some degree.

And yet, of course, by 1964 espionage had gained a new major connotation. It’s hard not to think of James Bond, not only because the Dynamic Duo’s globetrotting escapades keep taking them back and forth throughout Europe and Asia, but also because the central plot is as Bond as it gets – basically, the villain is trying to pit international powers against each other in order to take over the world!

I’m not the biggest fan of Sheldon Moldoff, but I admit that his work here – no doubt helped by Joe Giella’s inks – occasionally captures that luscious exoticism of the 007 pictures. I particularly appreciate the slick use of silhouettes in this sequence, first to highlight Batman & Robin and then to camouflage the Batplane:

It’s not just me. The intertextual link was fairly obvious – and, already at the time, reader Leonard J. Tirado picked up on it as well:

Batman #170

The comparison to Eric Ambler and Graham Greene is, needless to say, pretty out there. Those authors excelled at atmospheric authenticity and complex psychology, whereas Bill Finger is all about crisp, fat-free narrative and momentum, moving the plot at such a lightning pace that you hardly have time to settle into any particular situation (much less consider its logic or lack thereof).

Still, it’s true that Ian Fleming isn’t the only discernable influence here. I also see in ‘Zero Hour for Earth!’ the likes of Tintin and the sort of pulpy adventures and serials that later inspired Indiana Jones, especially when the Dynamic Duo find themselves in the jungle among some boobytrapped ancient ruins…

No holds are barred in this comic. Yes, the barrage of undeveloped ideas can make our enjoyment feel rushed – but it also generates an enjoyable rush. It’s A.D.D. fun!

In fairness, Fleming himself owed a debt to this strand of wild adventure fiction. Hell, in Dr. No the villain’s lair is also disguised by nature and superstition.

And, again, the scene where the Dark Knight and the Boy Wonder have to save the world by stopping the launch of a nuclear missile from an underground bunker (with eccentric decoration) would not look out of place on your average James Bond mission…

The thing is that saving the world isn’t the final climax of the story!

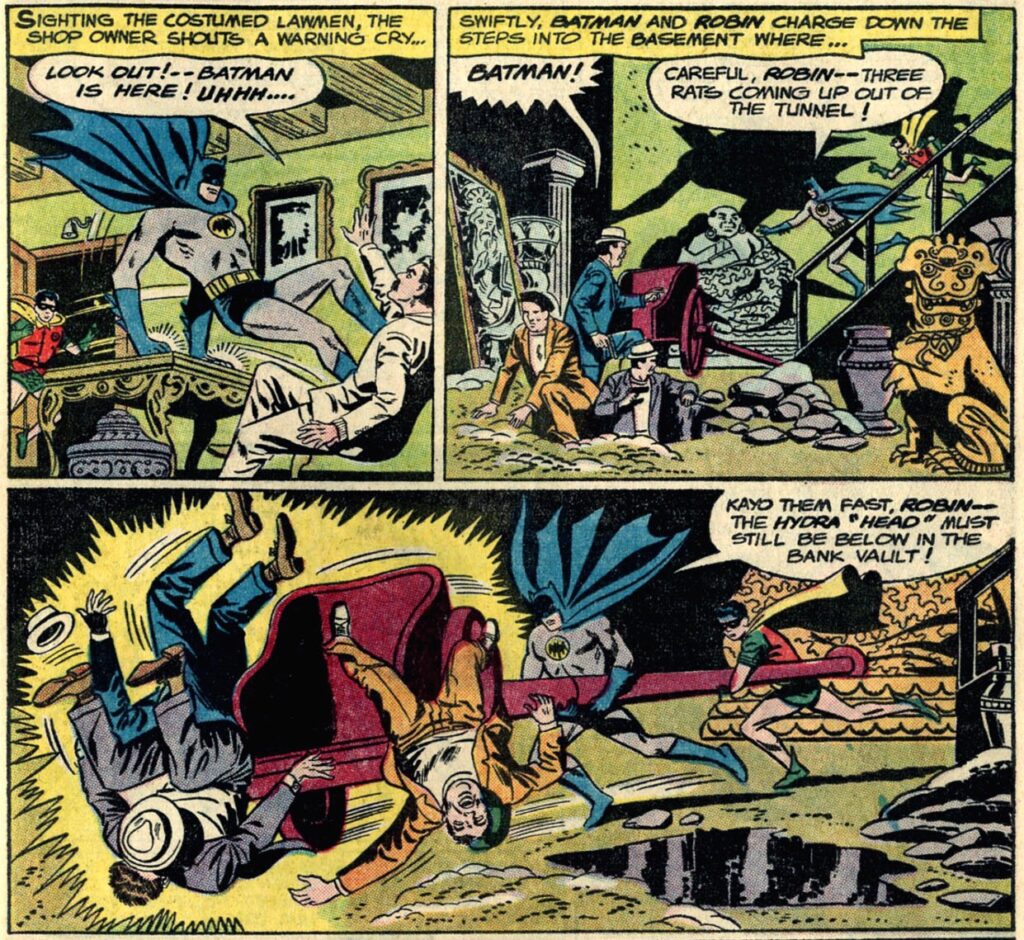

‘Zero Hour for Earth!’ is not a Bond venture after all. It is a Batman comic, goddamn it, which means that the worst villainy of all is urban crime, including larceny. So, after the Dynamic Duo have prevented nuclear war, the story shifts to traditional crime fiction as they move on to the more important business of preventing a bank heist:

This action-packed scene is STILL not the end of it!

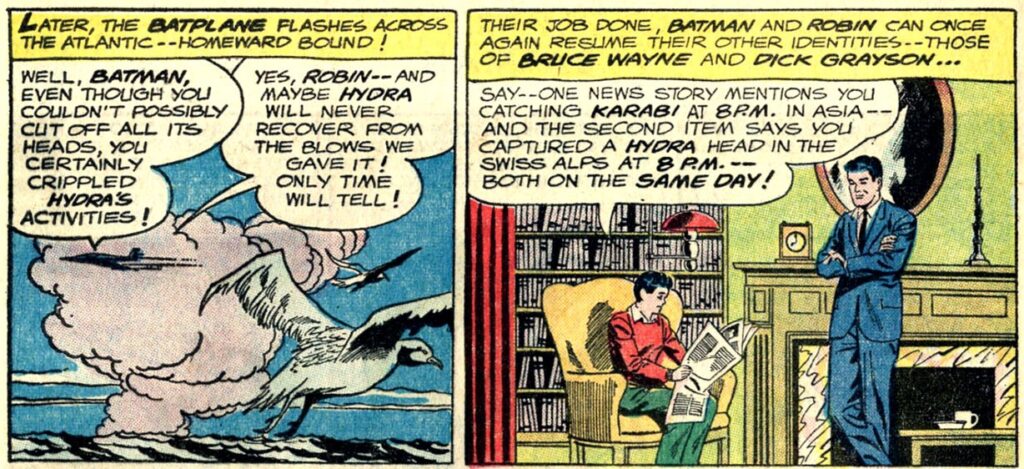

Returning to Bond-like thrills, we then get a heart-racing chase scene that anticipates the one in the movie On Her Majesty’s Secret Service by a few years *and* a nod to real-world Cold War geopolitics:

Bill Finger packs so much into these 24 pages… Today, the same basic plot would take at least six issues (twelve if written by Brian Michael Bendis) – and perhaps we might gain in terms of atmosphere and characterization, but we would surely miss in terms of breathless energy and a sense of excitement that doesn’t take itself too seriously.

That said, the most dated aspect of ‘Zero Hour for Earth!’ are the visuals. With minor tweaks, I can see Finger’s tale getting repurposed even today, as some creators continue to defy writing-for-the-trade decompression. Put a kickass artist on it and you could still get one hell a comic out of this script!

And yet, I don’t want to undersell the artwork too much. Ghosting for Bob Kane and aping his iconic style, Sheldon Moldoff can be a bit stiff, but his craftsman-like clarity and simplicity have their own appeal. For every crude panel, you often get another one that actually contains quite enjoyable and inventive imagery (like some of the ones I chose for this post). Thus, even after the ski-chase climax, Moldoff and Giella still give us a few lovely panels rendered in impressive detail… because this comic is all about surprising readers until the very last page!

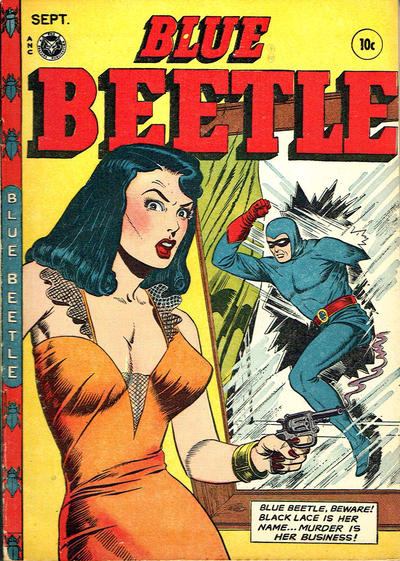

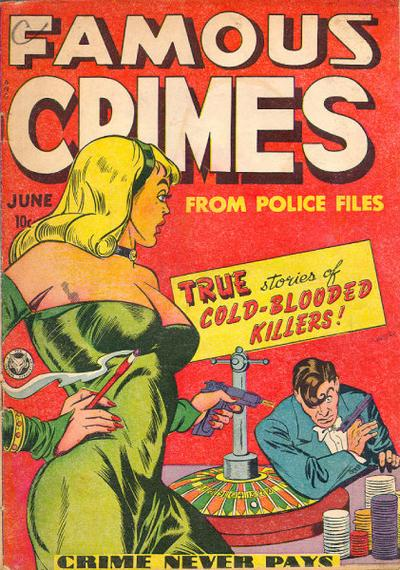

October’s first reminder that comic books can be awesome is a tribute to the voluptuous femmes fatales who were all over the covers of Golden Age comics:

The second post in this 12-part series about Cold War cinema focuses on the early 1950s, when the conflict reached its first peak, in Europe as well as in Asia. The films below are all profoundly shaped by the booming ideological rivalry and/or high-pitched security-driven mentality, but it’s fun to see how they approach these through a wide variety of stories and tones while focusing on such disparate fronts as the arms race, espionage, border division, hot wars, consumer diplomacy, financial aid, and full-on propaganda.

11. Seven Days to Noon (UK, 1950)

There’s an absorbingly gritty, semi-documentary feel to Seven Days to Noon, a taut thriller about the Scotland Yard running against the clock to stop a nuclear scientist from blowing up London. The fear that atomic power could be turned against the West is becoming increasingly palpable.

12. Peking Express (USA, 1951)

Take the train-bound intrigue of Berlin Express, have Joseph Cotton play the idealist American abroad like he did in The Third Man (here he’s a well-meaning doctor of the recently created World Health Organization), and set the whole thing in communist China… As an old-school adventure piece, Peking Express is serviceable enough, but its presence on this list is as a masterful lesson in Hollywood’s ability to recycle material into new geopolitical contexts, in this case updating proven formulas (this is the second remake of 1932’s Shanghai Express) to sensationalize the establishment of the PRC regime, back when it was still excluded from the United Nations (and therefore at odds with the WHO, which gives the film an extra layer of resonance when seen now). This one even has characters discussing Marxism and democracy in-between love scenes and gunfights, making it yet another representative of the HUAC era, which isn’t to say that things don’t get muddier along the way (the commies may not be the main villains after all!), culminating in a blaze of bullets where practically everyone is firing at each other.

13. The Steel Helmet (USA, 1951)

There aren’t all that many great Korean War movies. Less than a year into the conflict, though, Sam Fuller knocked out this incredible ragtag ‘lost patrol’ type of yarn. Shot in ten days, on a shoestring budget, with UCLA students as extras, The Steel Helmet wears a passionate sense of urgency on its sleeve and it packs one hell of a punch thanks to Fuller’s unmistakable instinct for tabloid filmmaking.

14. Europe ’51 (Italy, 1952)

Back to Italy! In the forceful melodrama Europe ‘51, we follow the postwar ideological turmoil through the eyes of a grieving mother searching for meaning among the capitalist bourgeoisie, communist ideas, and religion. By this stage, the Cold War has become such a hegemonic status quo than trying to find a place beyond it is perceived as a sort of insanity…

15. The Magnetic Monster (USA, 1953)

Despite the ‘monster’ in the title, don’t expect anyone in a rubber suit. The threat is actually an expanding radioactive isotope releasing an intense magnetic energy, with ever more devastating effects. What elevates this B-movie is its idiosyncratic approach to the genre: the first of a trilogy featuring the Office of Scientific Investigation (OSI), a fictional science-based version of the FBI (instead of G-Men, their agents are A-Men, because of the link to atomic energy), The Magnetic Monster is shot like an episode of Dragnet, presenting their investigation in a hardboiled, no-nonsense tone even as the premise becomes more fantastical and the stakes more world-shattering. In other words, not only do we get a story about nuclear research and danger, but we also get a dramatization of the protective role of the federal and military authorities.

16. The Man Between (UK, 1953)

Carol Reed’s thematic follow-up to The Third Man has a less sophisticated script, but the elegant cinematography and location shooting generate a truly immersive atmosphere, engrossingly portraying divided (if pre-Wall) Berlin and culminating in an impressive couple-on-the-run sequence (which is more reminiscent of Reed’s bleak IRA drama Odd Man Out). More than the films’ quality, though, the most interesting comparison to The Third Man concerns the ideological shift in emphasis, as pointed out by Tony Shaw in his book British Cinema and the Cold War: if, in the former movie, the Soviets ‘constituted only one threatening element that was far outweighed by the post-war racketeering of a distinctly non-political nature’ (as the criminal Harry Lime manipulated the system for his own purposes), in The Man Between ‘the communists are undoubtedly the main cause of Berlin’s instability’ (now they’re the ones blackmailing a smuggler).

17. Pickup on South Street (USA, 1953)

New York’s criminal underworld joins the Cold War. Like I mentioned last time I brought up Pickup on South Street, Sam Fuller’s walloping film noir features three of my favorite lowlifes in cinema, who find themselves way in over their heads when one of them inadvertently picks a wallet with top-secret government information…

18. Roman Holiday (USA, 1953)

Without much external context, the Cold War’s link to this endearing romantic comedy may appear mostly allegorical, as an American journalist shows a European princess a good time in Rome, symbolizing the US role in fostering the Old Continent’s freedom, happiness, and integration (while indirectly promoting tourism and, thus, consumer diplomacy). If you bear in mind that Roman Holiday was anonymously scripted by the blacklisted Donald Trumbo, however, its themes of trust and loyalty gain a whole other resonance against the unspoken backdrop of McCarthyism… And yet, ironically, the end-result was such a utopic advertisement for capitalism (anticipating the ‘economic miracle,’ this Italy is a world away from the Rome of Bicycle Thieves) that the US Intelligence Agency selected it as a priority export to the Eastern Bloc – and it did make it to Soviet screens due to the subsequent ‘thaw’ of the Khrushchev era.

19. Welcome Mr Marshall! (Spain, 1953)

A genuinely hilarious satire, made in the Franco dictatorship, Welcome Mr Marshall! chronicles a poor village’s attempt to impress the Americans when it turns out Spain might be included in the Marshall Plan after all.

20. Animal Farm (UK/USA, 1954)

What better way to wrap up this second post than with animated anti-Soviet propaganda commissioned by the CIA with the aim of showing viewers of all ages the degeneration of the USSR. Besides the object’s overall bizarreness, this screen adaptation of Animal Farm is especially fascinating when you consider the precise changes from George Orwell’s book.

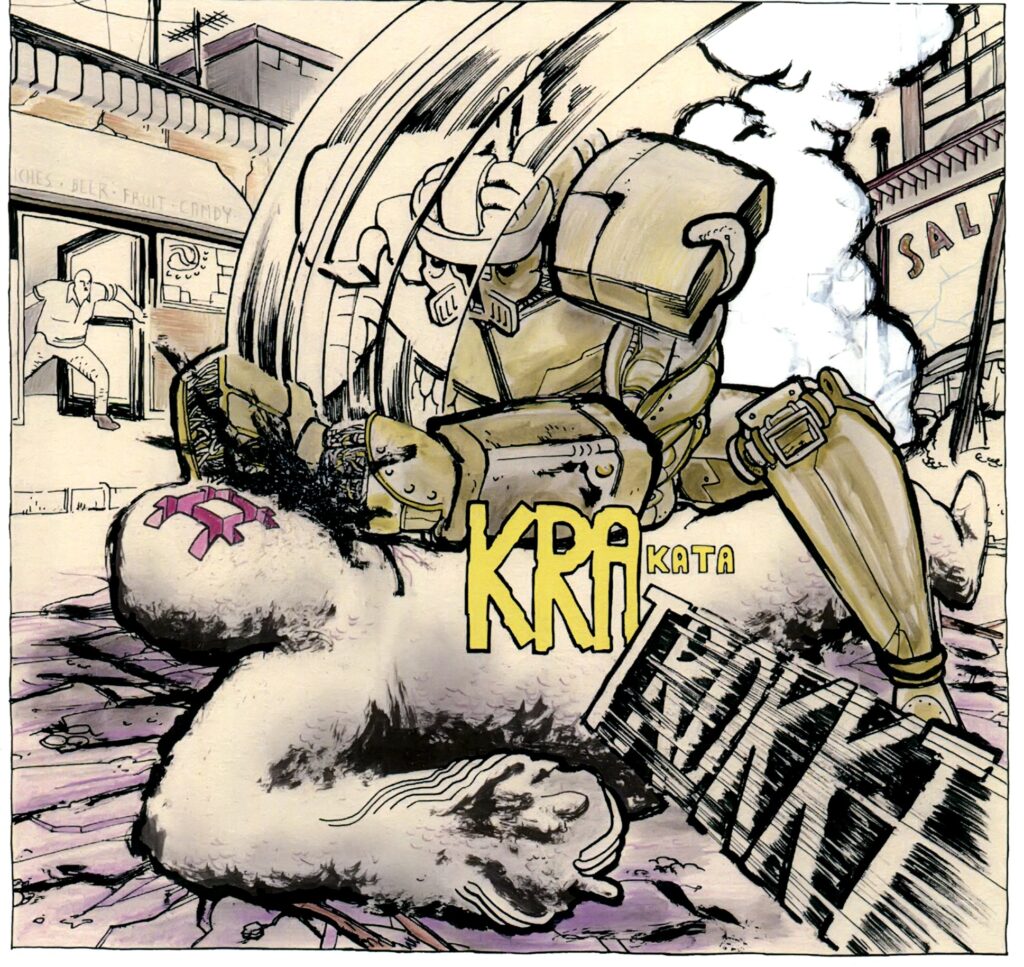

Just a reminder that comic books’ sound effects can be awesome:

Copra #3

This week we’re back to spotlighting comic book covers in Gotham Calling.

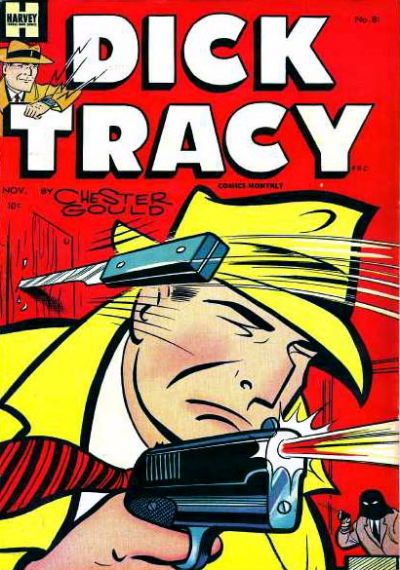

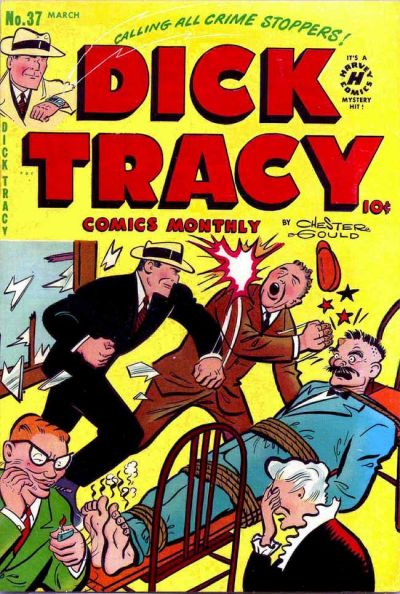

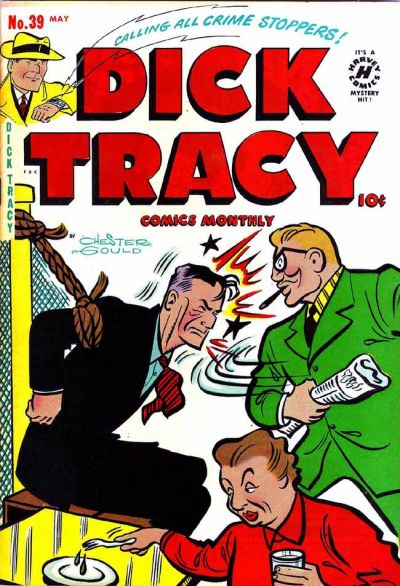

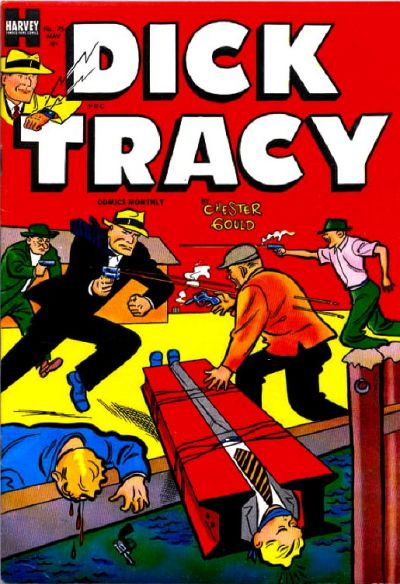

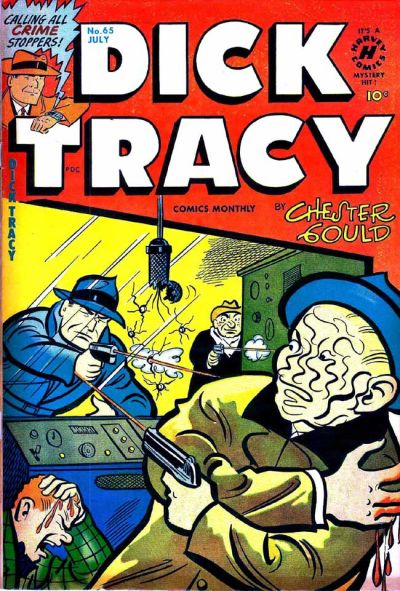

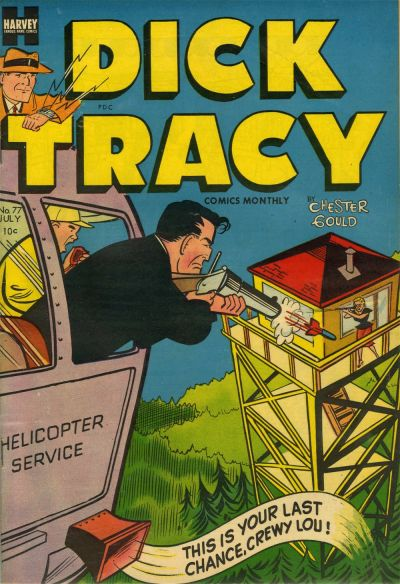

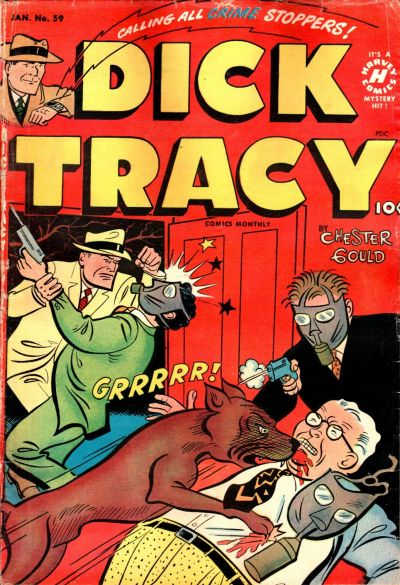

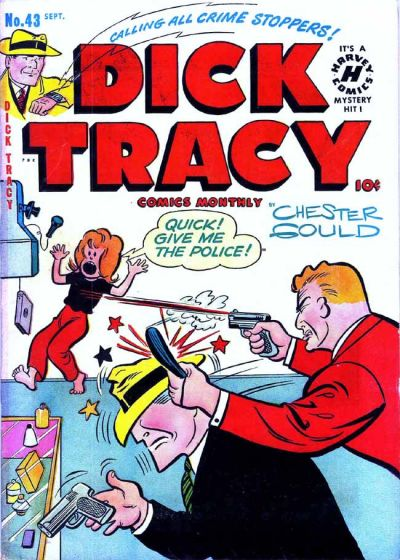

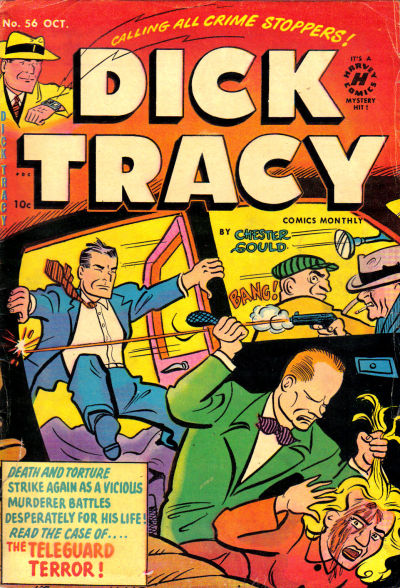

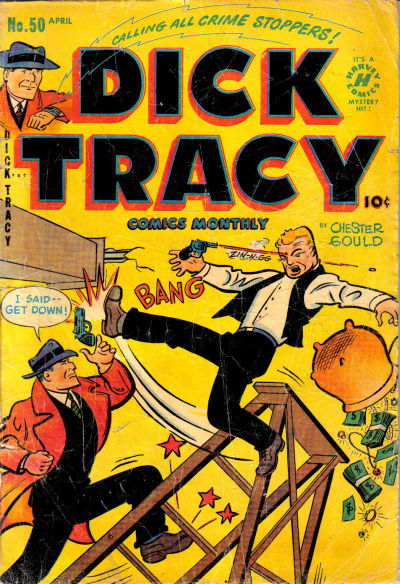

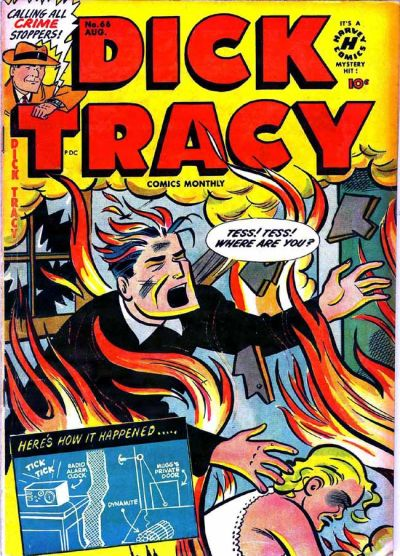

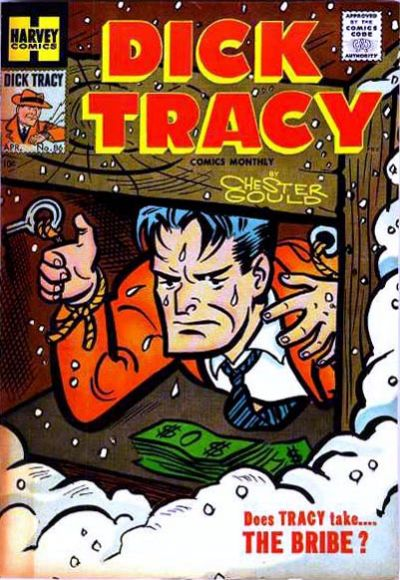

I’m quite fascinated by the work of Joe Simon on the covers of Dick Tracy back in the early 1950s, when monthly issues collected Chester Gould’s iconic daily newspaper strips about a tough, square-jawed police inspector’s crusade against organized crime.

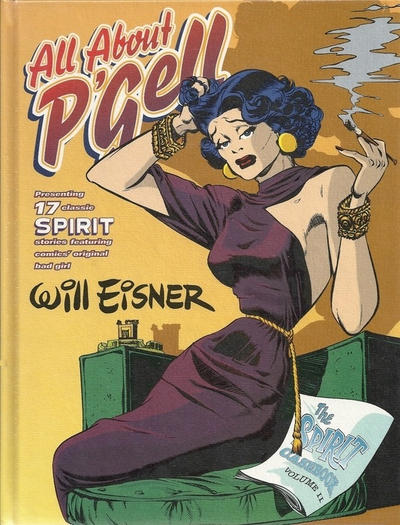

Because I first encountered Dick Tracy as a kid-friendly cartoon show and, later, as a surreal comedy film (where Al Pacino played his funniest gangster outside of Donnie Brasco, if not Scarface), for a long time I associated it with a relatively light, whimsical take on the crime genre, somewhere between Will Eisner’s The Spirit and Golden Age Batman comics. This means that, when I finally came across the original Dick Tracy stories, I was shocked and amused by how unabashedly sadistic they turned out to be.

I now realize that cruelty was as much a trademark of the series as the gadgets, the silly names, and the goofy-looking villains (Pearshape, Flaptop, Pruneface…). This spirit was certainly kept in 2018, when Dick Tracy was rebooted in the IDW mini-series Dead or Alive. Although superficially set in the present, that series emulated the original’s idiosyncratic brand of pulp, courtesy of a team of wonderful creators whose work had always seemed heavily inspired by Chester Gould’s comics in the first place (Rich Tommaso along with Lee, Michael, and Laura Allred).

In turn, while Michael Avon Oeming’s Dick Tracy: Forever began by returning the characters to their initial historical setting, for the most part that series substantially toned down the nastiness. Oeming’s artwork – colored by Taki Soma – looked absolutely lovely and the storytelling was pretty ambitious (gradually moving from a pastiche of Sunday strips into cyberpunk metafiction), but the result nevertheless felt somewhat sanitized and defanged in comparison to pre-Code comics…

As you can see above and below, the old comics pushed the contrast between colorful, naïve aesthetics and a committedly hardboiled tone to outrageous extremes. They’re full of blood, death, and torture, but there is also a cartoony edge to them, both in the caricatural character designs and in the overblown situations they depict.

Moreover, if there is one thing Joe Simon knew how to do was how to put together a striking layout (after all, he co-designed, with Jack Kirby, the mythical cover of Captain America Comics #1!). His covers for Dick Tracy are incredible pieces of storytelling, framing dynamic compositions with interlocked actions at multiple levels (usually playing with the foreground and background) so as to conjure up an elaborate scene – hell, almost an entire story – from a single image.

Whether showing the titular protagonist getting viciously attacked or featuring him mercilessly inflicting pain on outlaws, the covers drawn by Joe Simon (ghosting for Gould) aren’t mocking film noir or distorting old Dick Tracy comics – they ARE old Dick Tracy comics (even if the strip had been around for over twenty years by the time these specific collections came out). They’re also not spoofing police brutality or the panic over racketeering, since the series seems very clearly on the side of authority. In fact, Simon’s covers do perfect justice to the stories inside. And yet, retroactively, they came off as misleadingly iconoclastic in my eyes – their violence not only perversely thrilling, but comically grotesque.

Here are a few more bombastic examples that made me feel this way:

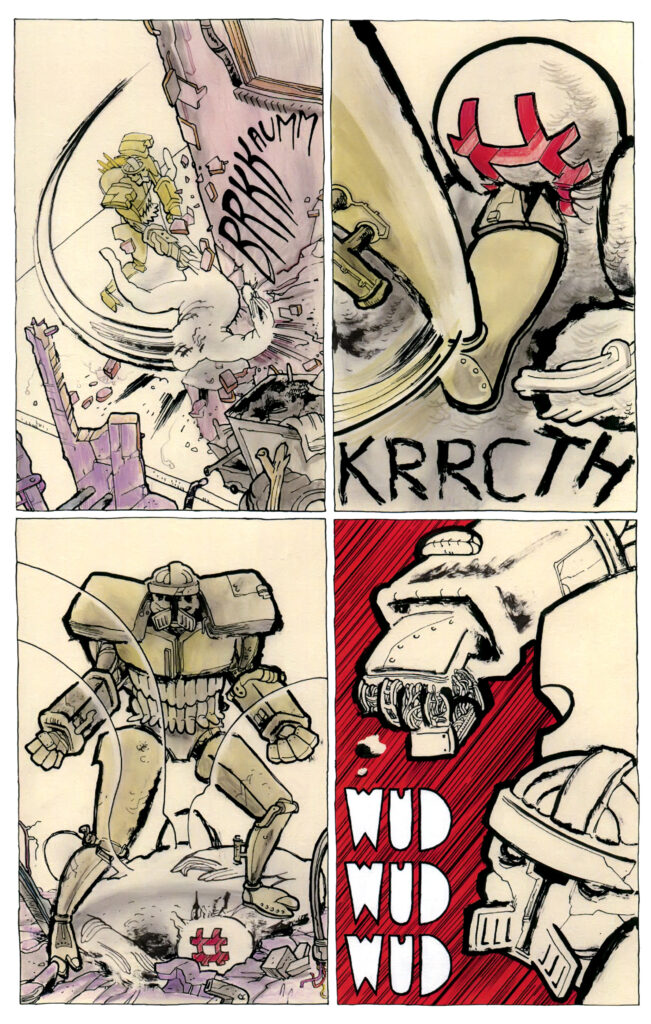

A freaky reminder that comics can be awesome…

Decorum #3

It’s Gotham Calling’s ninth anniversary!

This past year was especially irregular in terms of posting because I had more classes than usual, but I’ve finally found a way to turn this in the blog’s favor. One of my courses looked at how popular culture imagined the Cold War as it unfolded, so I spent much of the year watching, rewatching, discussing, and thinking about films from that era… And so, since I like to celebrate Gotham Calling’s landmarks with longer listicles or compilations, this time I’m providing a selection of 120 movies made both during and about the Cold War.

I’m working on a longer project about this but, for now, I’ll just share a preliminary list (spread over twelve biweekly posts). It is hardly exhaustive or balanced: there is way more West than East and most productions are from the United States and Europe despite the fact that the Cold War affected culture all over the globe…

In other words, many key episodes and features of the Cold War are missing, as are plenty of ‘iconic’ movies that I don’t find as appealing as the ones below. Still, if you binge-watch all of the ones I selected, especially in chronological order, you’re bound to get quite an immersive – and, I hope, occasionally surprising – experience and come out of it with a wider understanding of how the Cold War was visualized at the time.

As for the selection criteria, the main thing was whether I found a film both genuinely entertaining and interesting in terms of what it suggests about the Cold War (i.e. propaganda is a feature, not a bug). My definition of the Cold War is quite broad, ranging from the arms race and proxy conflicts to the sheer competition between capitalist and socialist models of modernity.

That said, I had to limit the list somehow – so, while there are some allegories in there, I privileged films where the references to the conflict were relatively textual (and not just in the subtext). By themselves, archetypical metaphors and themes such as space exploration, alien invasions, secret government programmes, and brainwashing weren’t enough to automatically merit inclusion… although you will certainly find at least one instance of each of these elements on the list.

The end result is pretty eclectic, which suits the spirit of Gotham Calling. Some entries are stirring pieces of filmmaking and storytelling by themselves, others are fascinating specifically because of their production context. And while they’re all fiction, contrary to this blog’s primary focus not all of them fall into what is conventionally designated as ‘genre fiction.’ That category can sometimes be useful to quickly identify stories that are shamelessly formulaic and unpretentious (like Batman comics), but it can also prove limited and misleading… After all, let’s face it, classical dramas and comedies are themselves genres with their own formulas, traditions, subgenres (e.g., family drama, slapstick comedy…), and popular appeal.

In this case, I’m approaching Cold War cinema as a genre in itself, i.e. as a set of recurrent themes, tropes, and imagery that may draw common interest in all of these – otherwise quite varied – films.

1. Berlin Express (USA, 1948)

Berlin Express is a very fun Hitchcock-like thriller, despite being depressingly set in bombed-out Germany, where a group of men – and a woman – from the USA, UK, France, and USSR come together… and the Cold War doesn’t yet seem inevitable. Like some of the movies below, it was filmed against the backdrop of actual German rubble, thus capturing the materiality of the place at that moment in history, even while absorbing it into an unabashedly artificial narrative.

2. Bicycle Thieves (Italy, 1948)

If you want to get a sense of the reasoning for the Marshall Plan and for the United States’ interference in Italy’s 1948 elections (i.e. why Washington thought communism had a chance in Western Europe), there are worse places to look for it than in the neorealist classic Bicycle Thieves, whose depiction of Rome’s poverty-stricken lives stands in stark contrast to the escapist glamour of American cultural imperialism (as reflected in the street posters, which play a key role in the plot).

3. A Foreign Affair (USA, 1948)

An absolutely scathing satire of the Allied occupation of Germany. Hopping from political screwball comedy to romance to musical to social drama to noirish spy thriller and back again, A Foreign Affair embodies the abrasive energy with which, along with the military, Hollywood also traveled to war-torn Europe to rebuild its imaginary. (Although Italian neorealism powerfully filmed the same locations and similar situations in Germany Year Zero, its sombre approach to the literal and moral ruins of post-fascist Berlin strikes me as more contemplative of the past than of the future… and therefore less indicative of the looming Cold War compared to the ‘anything goes’ attitude of A Foreign Affair.)

4. Krakatit (Czechoslovakia, 1948)

A nightmare on screen. Blending gothic horror with science fiction, Krakatit inaugurates the apocalyptic angst of the atomic arms race (even though it was made back when the United States still had a nuclear monopoly) through the bewildering saga of a man who discovers a powerful explosive and desperately tries to prevent its weaponization. The expressionistic lighting and unsettling camerawork, along with surrealist, steam-of-consciousness storytelling, deliberately emulate a feverish hallucination.

5. Passport to Pimlico (UK, 1949)

In Passport to Pimlico, a London area suddenly declares independence from the United Kingdom, leading to an original – and quite funny – take on postwar rationing, the Berlin airlift, and decolonization.

6. The Third Man (UK/USA, 1949)

The greatest film noir ever (as repeatedly stated at Gotham Calling), The Third Man is a mystery set – and shot – in occupied Austria, where, once again, the main tension is not so much between East and West as between the United States and Europe.

7. Tokyo Joe (USA, 1949)

In turn, Tokyo Joe tends to be remembered – when it’s remembered at all – as little more than a competent noiry crime drama (with a touch of Caniff-esque aerial adventure), albeit elevated by Humphrey Bogart’s world-weary charisma. From a Cold War perspective, though, this depiction of occupied Japan provides a remarkably neat counterpart to all those movies about postwar Europe, begging for a comparison of their plain similarities and sharp contrasts.

8. The Woman on Pier 13, aka I Married a Communist (USA, 1949)

If Tokyo Joe has been ignored, this home front noir has been utterly reviled. The tragic tale of a San Francisco shipping executive getting blackmailed by the US Communist Party (practically indistinguishable from an organized crime racket), The Woman on Pier 13 is often maligned – and mocked – as an epitome of hysterical Red Scare propaganda. While that’s not entirely unfair when it comes to the production’s spirit, interestingly the result is more ideologically jumbled (as compellingly argued by Robert Miklitsch). It’s also a pretty stylish affair, with plenty of hardboiled dialogue, white-knuckle action, and stunning chiaroscuro cinematography. (The corruption of dockworkers’ unions was soon to be the object of a much more – deservedly – acclaimed picture, On the Waterfront, but the anti-communism in that one is largely subtext, implicitly justifying director Elia Kazan’s decision to denounce fellow leftists to the House Un-American Activities Committee.)

9. The Big Lift (USA, 1950)

The flip side of A Foreign Affair is this slickly crafted semi-documentary dramatizing the conflicted re-establishment of relations with (some) Germans: written during the Berlin Blockade and shot on location immediately afterwards, with the collaboration and supervision of the United States’ military, The Big Lift ostensibly presents a more benign view of the American forces (between this and 1948’s The Search, Montgomery Cliff started his film career as the friendly face of uniformed compassion for Europe…). Yet the final product is itself engagingly multi-layered, resorting to various clever and amusing strategies to convey – and even, to some extent, problematize – western discourse about this inaugural event of the Cold War.

10. Destination Moon (USA, 1950)

Despite a few precedents, Destination Moon is the epic that truly kicked off the cinematic space race, anticipating future technology through hard science fiction while channelling the politics of its day in the form of jingoistic warnings against a foreign enemy, not to mention a staunch commitment to the superiority of corporate capitalism. What a time capsule!