Crisis on Infinite Earths #2

I was hoping to be back to longer posts this month, but it has been one hell of a year, so I’ll just stick to the regular COMICS CAN BE AWESOME section for a while longer. It’s not as if I haven’t been able to read at all – for instance, I’ve been making my way through the gorgeous collected editions of The Rise and Fall of the Trigan Empire and I finally caught up with Mark Waid’s and Dan Mora’s DCU geekfest World’s Finest. The latter is a colorful throwback to the Silver Age (or, better yet, a colorful throwback to the JLA‘s colorful throwback to the Silver Age in the late 1990s), with Robin’s and Supergirl’s date in issue #12 being an instant classic. Plus, in terms of prose, I just got through a fun little spy adventure by a crime writer (Agatha Christie’s Destination Unknown), a very nifty crime yarn by a master of spy fiction (Mick Herron’s Nobody Walks), a white-knuckle thriller that ventures into political intrigue (Desmond Bagley’s The Freedom Trap, which turned out to be a stealth sequel to his Running Blind), and a politically charged novel that, for the most part, reads like a damn thriller (Vassilis Vassilikos’ Z). It’s just that I don’t have the time to write much about them… Although I’m confident I’ll manage to properly revive the blog in September.

In the meantime, I’m leaving you with one of these irregular tone-association posts listing ten movies that feel like Batman yarns… except, you know, without Batman. I’ve grown less and less interested in straight-up adaptations of comics and superhero films, but I’m continuously fascinated by these looser connections across media.

The Creeping Unknown, aka The Quatermass Xperiment (1955)

When a rocket crash lands on the English countryside, it turns out astronauts may have brought a mutating alien organism back with them… We find this step by step as The Creeping Unknown absorbingly follows the authorities’ investigation (including a classic Cold War clash between science and security forces), effectively shot in a tense, noirish, and sometimes quasi-documentary style. Fans of Batman’s dark sci-fi strand (your Gotham by Midnight or the type of stuff collected in the Batman: Monsters paperback) should definitely track down this first installment in Hammer’s series of horror mysteries starring the two-fisted rocket scientist Bernard Quatermass, which – with their giddy gore, cool technobabble, and dark wit – are like having direct access to Warren Ellis’ subconscious.

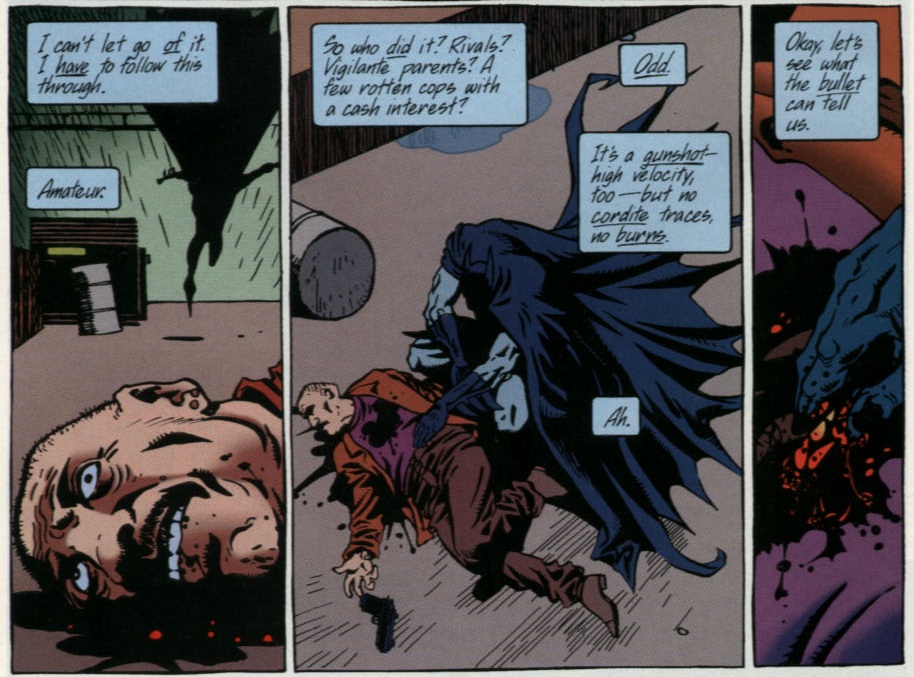

Legends of the Dark Knight #83

****************************************************************************************

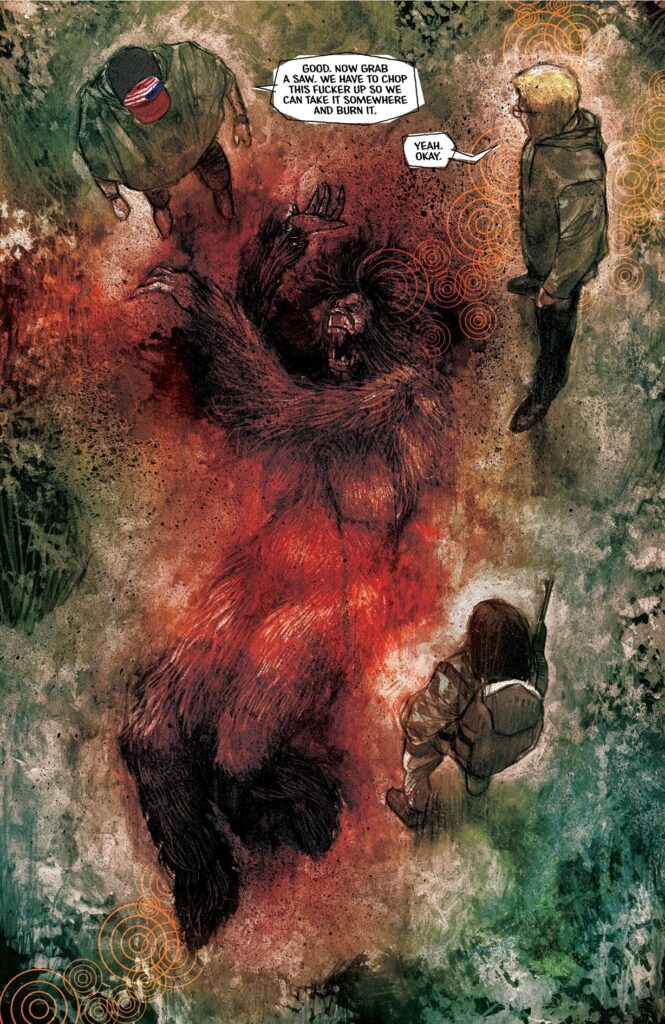

Barbarian (2022)

Another type of horror in Batman stories tends to be more psychological, with twisted villains doing fucked up things, so I think it also makes sense to recommend this shocker from last year. Barbarian has so many twists and turns that any attempt to summarize it is bound to spoil some of your enjoyment, so I will just highlight the initial sequence, in which a young woman arrives at an Airbnb (in a derelict Detroit neighborhood) and finds a man inside who claims the house has been double-booked. The film then expertly stretches the tension by letting our own prejudices and expectations do the heavy lifting as each friendly gesture can be read as threatening, each coincidence carries ambiguity, and each little hint feeds off our suspicious nature (plus the fact that we know we are watching a horror movie and that, therefore, something horrific is bound to happen sooner or later). Writer-director Zach Cregger skillfully exploits the fears du jour, topically drawing on identity politics and sexual scandals but, for the most part, he does it implicitly and trusts us to fill in the gaps. In fact, it takes a while before we get to something that feels like it would belong in a Batman comic, although we do end up in a place that could make Scott Snyder jealous… (You can find an interesting spoiler-heavy analysis here.)

Detective Comics #874

****************************************************************************************

Desperado (1995)

Antonio Banderas is a mariachi who roams around Mexico with guns in his guitar case looking for the boss of the man who killed his lover… and, sure enough, he slaughters plenty of other bastards along the way. Drawing on spaghetti westerns as well as on Hong Kong’s gun fu cinema, Robert Rodriguez’s second feature has enough gonzo action, offbeat humor, and quirky criminals to look like a Garth Ennis comic come to life (yet without reaching the cartoony levels of Machete), so I’m throwing in this one for all the fans of the largely Gotham-set Hitman series.

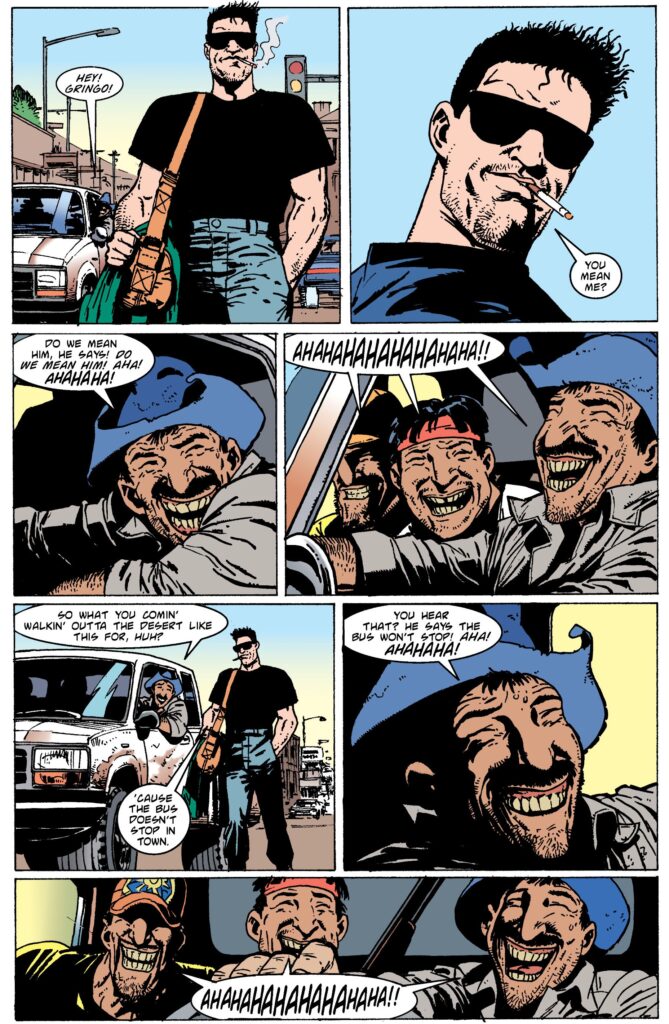

Hitman Annual #1

****************************************************************************************

Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922)

As far as I can tell, Dr. Mabuse the Gambler is the movie that truly popularized the kind of mad archcriminal mastermind that the Caped Crusader would regularly face throughout his career. I can easily imagine the likes of the Penguin, Black Mask, or Hugo Strange (who is also a hypnotist, a manipulative psychoanalyst, and a master of disguise) behind the string of idiosyncratic capers that fill over four hours of this absolutely brilliant, engagingly paced silent classic, not least because the deeply eerie atmosphere and expressionist rendition of Weimar Berlin’s shadowy streets and lavish nightclubs continue to inspire my platonic vision of Gotham City to this day. The thing is that the World’s Greatest Detective is not around to destroy Dr. Mabuse (hell, Batman hadn’t even been created by the time the film’s first sequel came out, ten years later!), so the only hope is for Mabuse to somehow destroy himself…

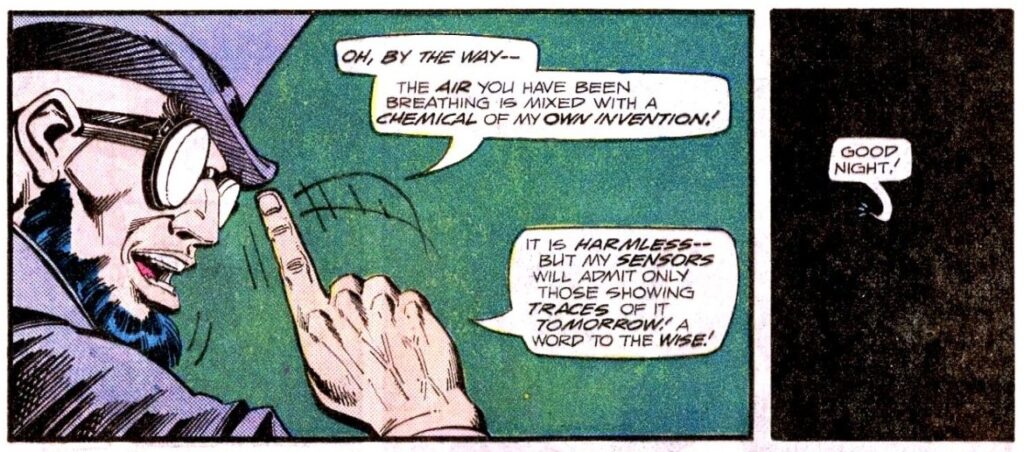

Detective Comics #472

****************************************************************************************

The Fly (1986)

Be afraid. Be very afraid. With its science-gone-wrong horror and tragic villain whose downfall derives from his human emotions (even if they get distorted along the way), David Cronenberg’s cult remake of The Fly is exactly the kind of tale you’ve read in Batman comics hundreds of times, but, again, the difference here is that you can’t count on the Dark Knight to jump in and save the day. When it comes to the rogues’ gallery, although the most obvious visual connection is to Charaxes, storywise the closest parallel is to Kirk Langstrom, a scientist whose efforts at improving humanity also lead him into a monstrous path… Indeed, the designs on the film’s final stretch could’ve plausibly come from a young Flint Henry working his way into drawing Man-Bat.

Man-Bat (v2) #1

****************************************************************************************

In the Mouth of Madness (1994)

After an extended prelude in a hyper-stylized mental hospital that could be Arkham Asylum, we are treated to the story of a misanthropic insurance investigator (played by Sam Neill, who fully commits to the weird material much like he would do with the not-too-dissimilar Event Horizon a few years later) looking for a missing bestselling author (shamelessly modeled after Stephen King) whose fictional Lovecraftian horrors appear to be coming to life. This gothic thriller might as well be one of those metafictional shenanigans in which Batman finds himself every once in a while, especially if written by Peter Milligan. As he’s prone to do, however, director John Carpenter pushes things to the limit, creating the sense of a world already descending into chaos anyway, so the hysterical tone actually feels closer to an Alan Grant comic!

Arkham: Devil’s Asylum

****************************************************************************************

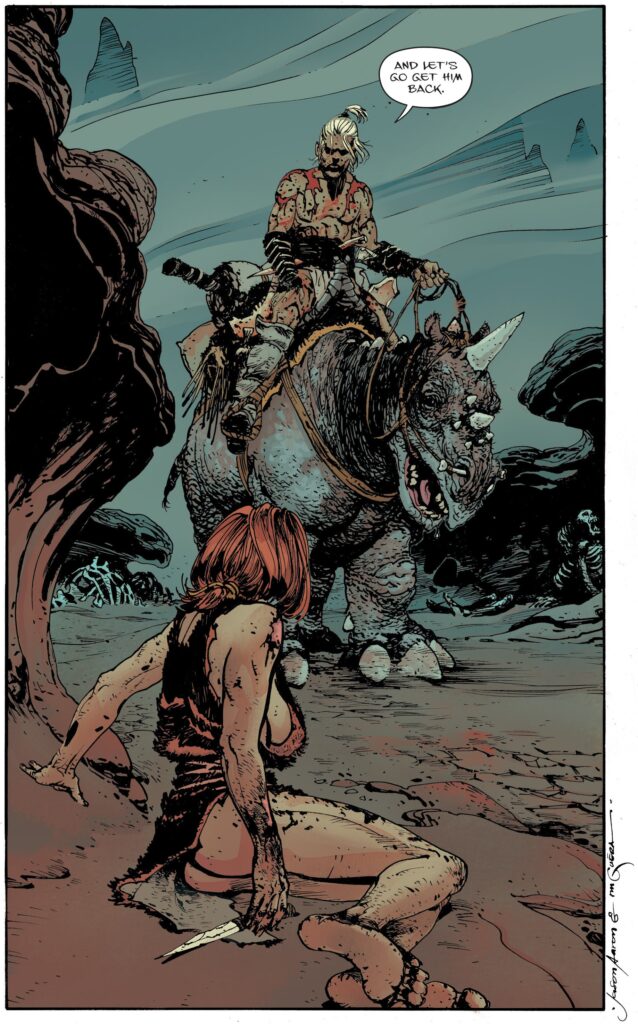

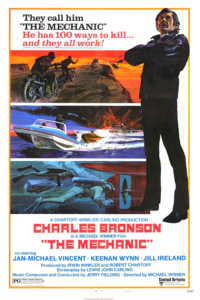

The Mechanic (1972)

If Bruce Wayne had devoted his life to murder rather than to preventing it, he might’ve turned out like Charles Bronson’s character in this movie: a rich, methodical, resourceful assassin who decides to take a protégé under his wing. That said, from the lengthy portions of dialogue-free planning and execution to the occasional semi-philosophical conversations, The Mechanic is clearly emulating the works of Jean-Pierre Melville… and while director Michael Winner – like the pupil in the film – can’t really match his master, it’s a lot of fun to watch him try.

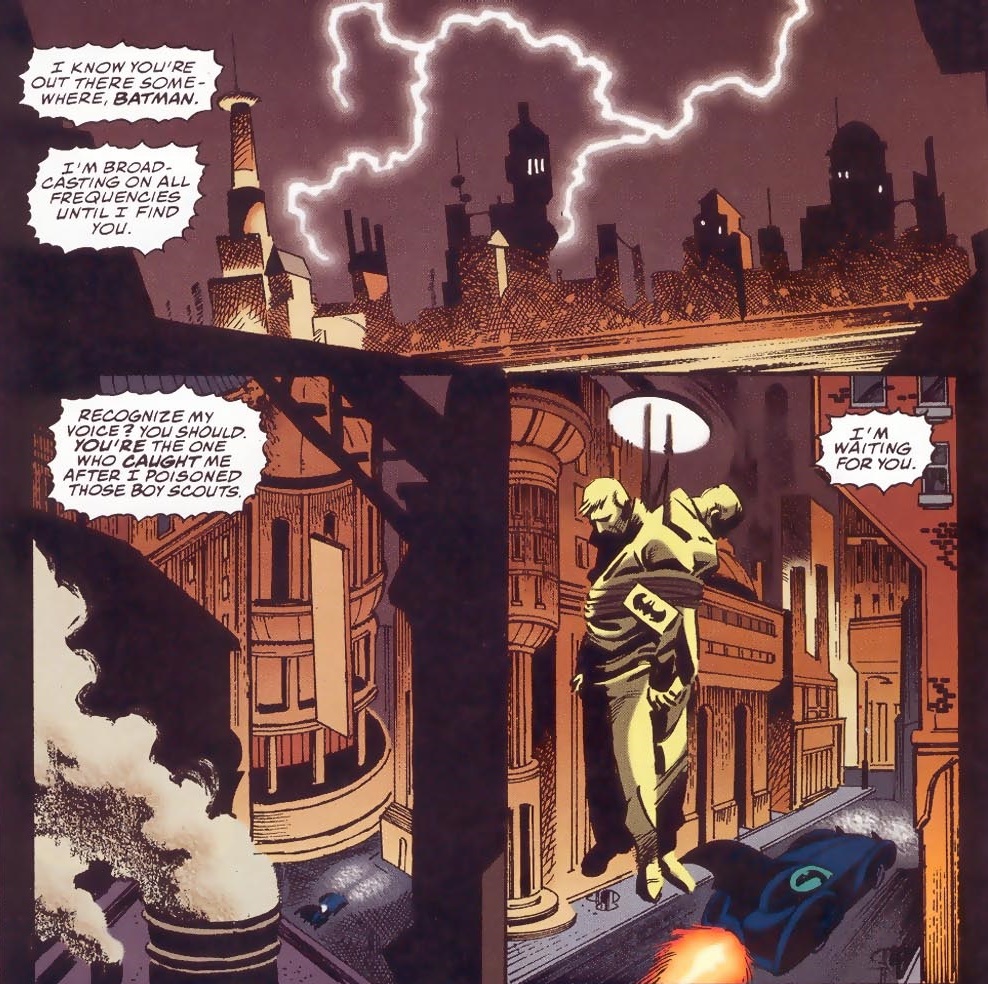

Detective Comics #795

****************************************************************************************

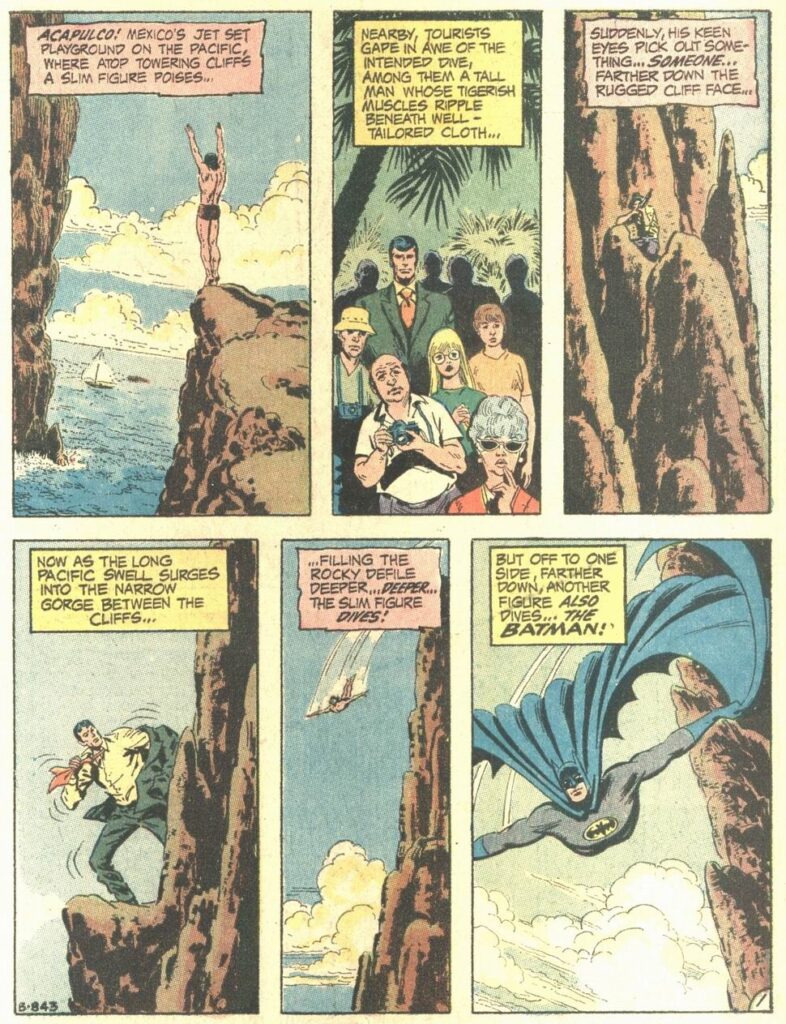

Mexican Slayride (1967)

It’s about time I included a Eurospy in one of these lists. After all, these 1960s’ James Bond knockoffs (with a much lower budget) were lurid, violent, and somewhat campy adventure films whose groovy tone and set pieces wouldn’t look out of place on an issue written by the likes of Bob Haney or Denny O’Neil. This is certainly the case with Mexican Slayride, where globetrotting French agent Francis Coplan chases a bunch of paintings stolen by the Nazis during World War II and finds himself among a ludicrous barrage of deathtraps, secret passages, and slugfests galore, shot and edited with a keen eye for neat transitions – not to mention adorable special effects – that also bring to mind comic-book storytelling. That said, although the stylish Coplan sometimes manages to pull off a Bruce Wayne vibe, he is no Caped Crusader, as he keeps viciously killing and/or screwing his way through the entertainingly disjointed narrative… until the bonkers finale!

The Brave and the Bold #97

****************************************************************************************

Mr. Arkadin (1955)

With a knife on his back, on a Naples port, a dying man gives a smuggler just enough hints about a dark secret of the Russian oligarch Mr. Arkadin to launch him on a quest spanning much of postwar Europe as well as a few sites in North Africa and Southern America, meeting all sorts of eccentric underworld figures along the way. The pace is so frantic, the characters so grotesque, and the cinematography so baroque that you may watch Mr. Arkadin either as a fun example of the kind of pulpy, go-with-the-flow adventure mystery that you can also find in old-school Batman comics or as a diabolically overblown parody of the whole damn genre of international intrigue (it’s like a coked-up take on The Mask of Dimitrios). Scripted, directed, and produced by Orson Welles, who also stars as the sinister Arkadin (who one could see joining the Black Glove organization, hence the film’s inclusion on this list), this is also a fascinating American view of Europe as a chaotic, crime-ridden continent in constant ebullition, marked by both jet set debauchery and archaic rituals, with everyone shuffled around by a confusing mess of wars and revolutions.

Batman #676

****************************************************************************************

Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988)

This surrealist black comedy set in a version of 1947 Los Angeles where cartoons are living creatures is shaped like a pastiche of noir mysteries, complete with an alcoholic private eye at the center (played by Bob Hoskins) and an unforgettable night club act. Who Framed Roger Rabbit? finds a neat equilibrium – the whole thing works because Hoskins and the rest of the live-action cast play it relatively straight, even when being harassed by a hysterical cartoon rabbit. Although less outright comedic, Batman yarns often go for a similar type of equilibrium, counterintuitively merging tropes of detective fiction (that most rationalist of genres) with unbridled fantasy (where a key appeal is watching the impossible unfold), as in the superhero extravaganza that is the latest iteration of World’s Finest…

Also, the Dark Knight has actually fought against Elmer Fudd:

Batman / Elmer Fudd