Just in case you needed another reminder that Batman comics can be awesome…

Batman: Earth One

Gotham After Midnight #2

Joker: Last Laugh #2

Just in case you needed another reminder that Batman comics can be awesome…

Batman: Earth One

Gotham After Midnight #2

Joker: Last Laugh #2

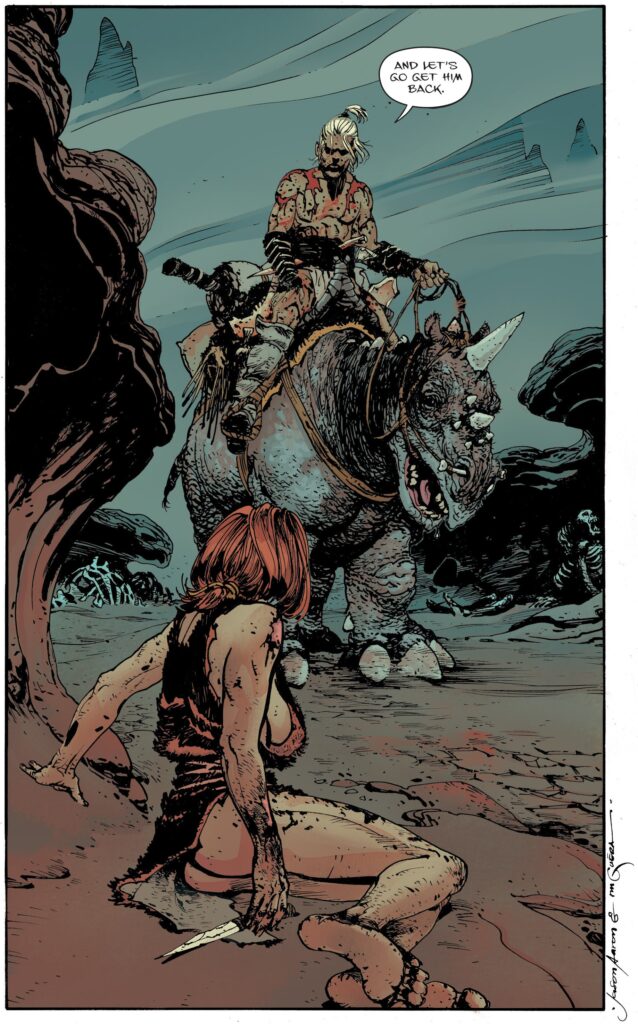

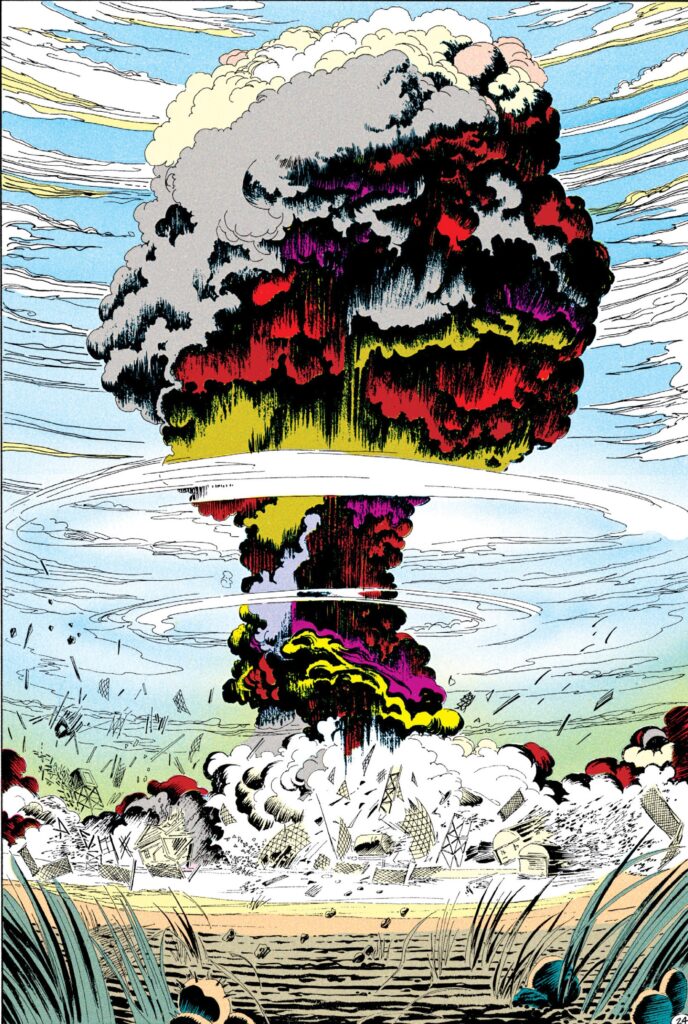

In this month’s reminders that comics can be awesome, let us revisit the adrenaline-charging impact of well-crafted double-page spreads:

Jonna and the Unpossible Monsters #1

Ultramega #1

Kane and Able

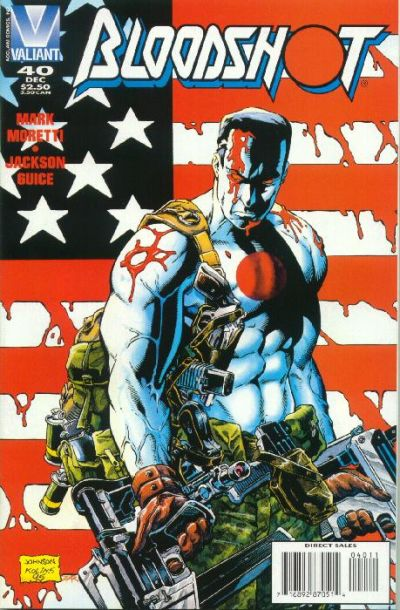

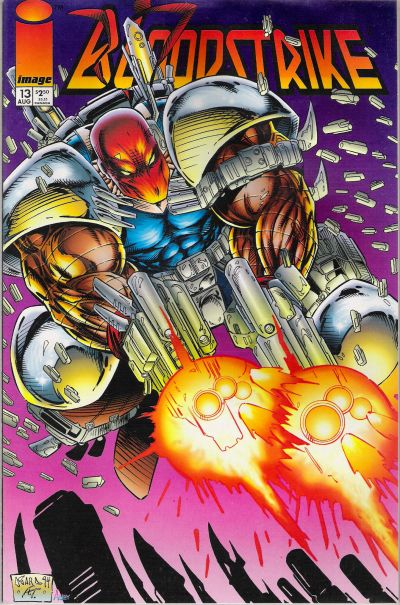

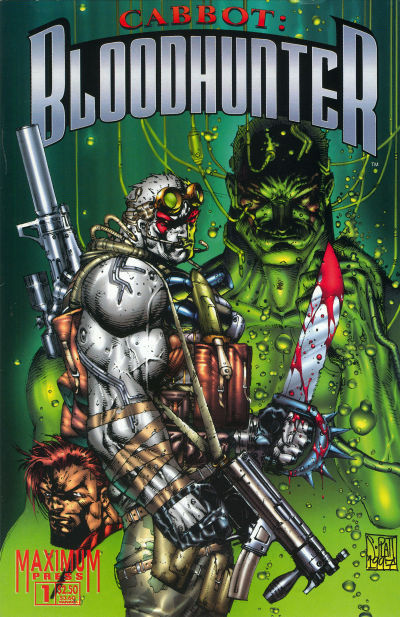

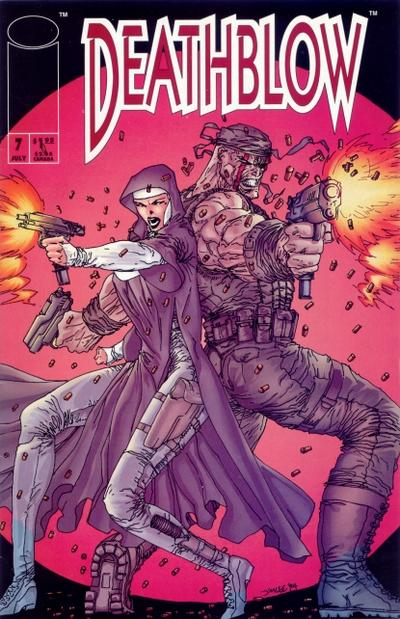

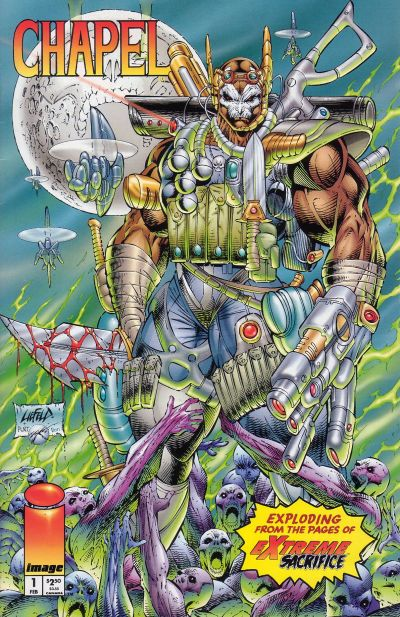

Let’s finish this month’s reminders that comics can be awesome by going back to the ‘90s, when covers raised absurd macho bullshit to hilarious extremes, displaying the kind of shamelessly dumb and eagerly badass attitude still echoed in recent films like Sisu and John Wick: Chapter 4.

If the former is basically John Wick in WWII Finland, the latter actually turned out to be a sad case of diminishing returns: the first John Wick worked as a minimalistic revenge thriller with a somewhat quirky take on a familar genre, the second film pushed the visuals to an almost art-house level while entertainingly escalating the stakes to unexpected degrees, and the third one provided a relentless barrage of effective and inventive action set pieces, but this final chapter feels like just more of the same without any of the original freshness. Still, at its best (the Osaka Continental free-for-all, the instant classic fight at the Rue Foyatier staircase, Wick weaponizing traffic around the Arc de Triomphe), Chapter 4 has the flavor of those trashy comics from an era when everyone seemed to think ‘blood’ was the coolest thing you could name a series…

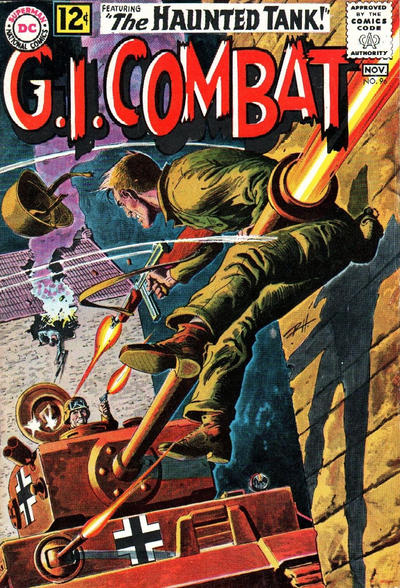

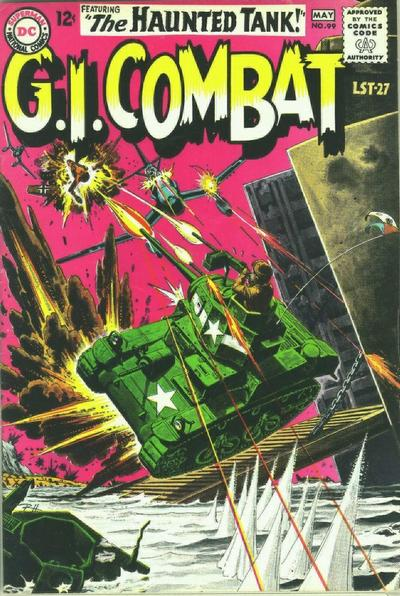

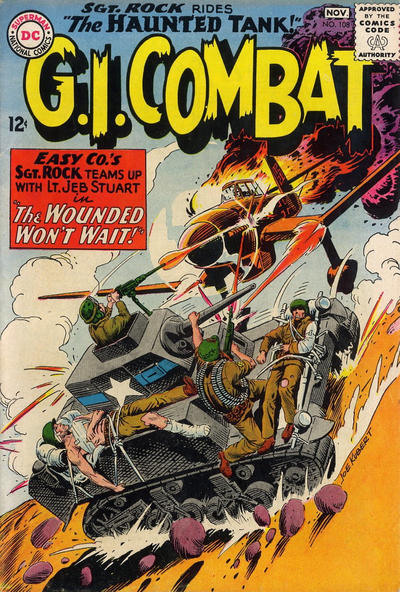

This weeks’ reminder that comics can be awesome is a tribute to the long history of tank covers at DC:

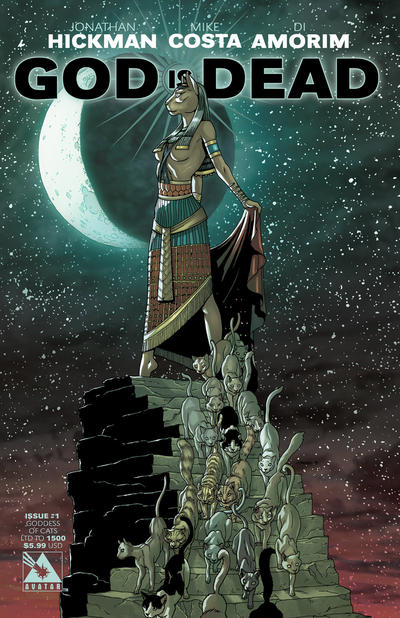

Your reminder that comic book covers can be awesome, God Is Dead edition:

Your reminder that old-school romance comic-book covers can look awesome.

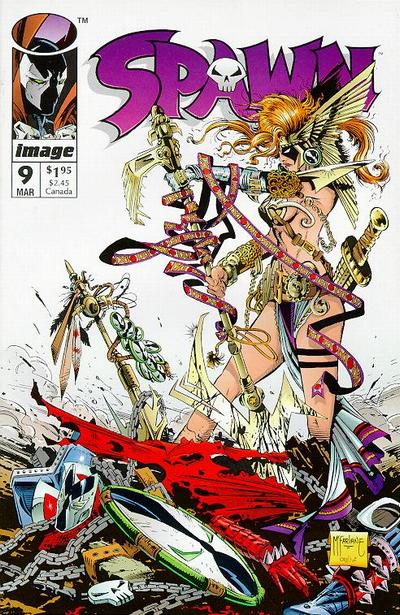

In this month’s reminders that comics can be awesome, we’re going back to spotlighting covers. Let’s start with a trio of representative covers from the 1990s which live up to that era’s reputation for violent, ultra-muscled men, highly sexualized women, and just a general unabashed embrace of excess…

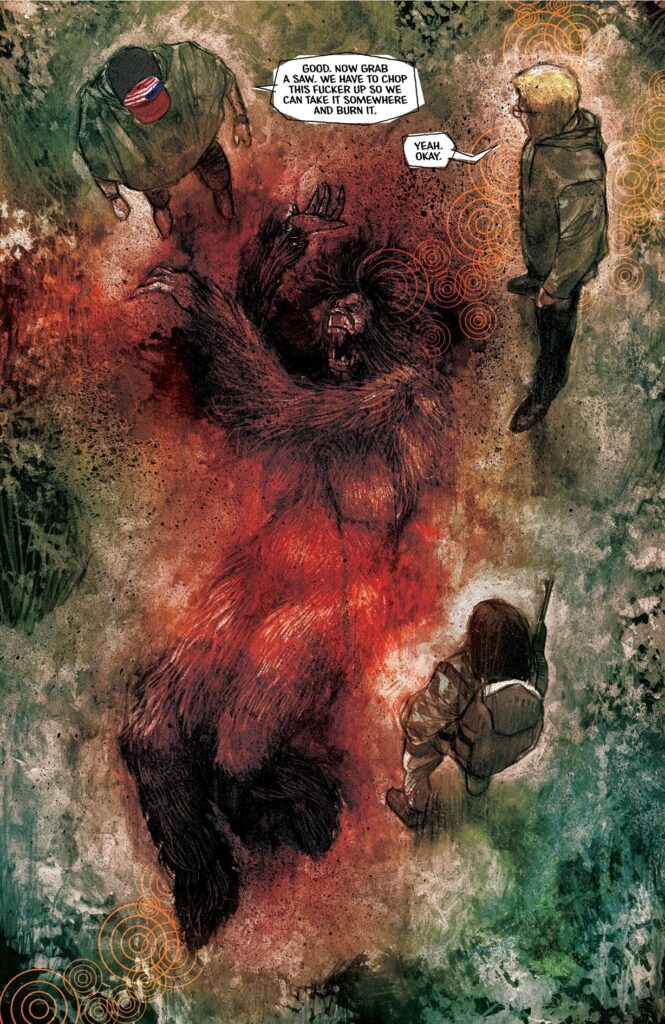

A moody reminder that comics can be awesome…

Step by Bloody Step #1

The Department of Truth #11

The Goddamned #2

Yes, it’s time for another hiatus. As usual, the Monday reminders of comic-book awesomeness will continue, but the longer Thursday posts will probably only be back in the summer.

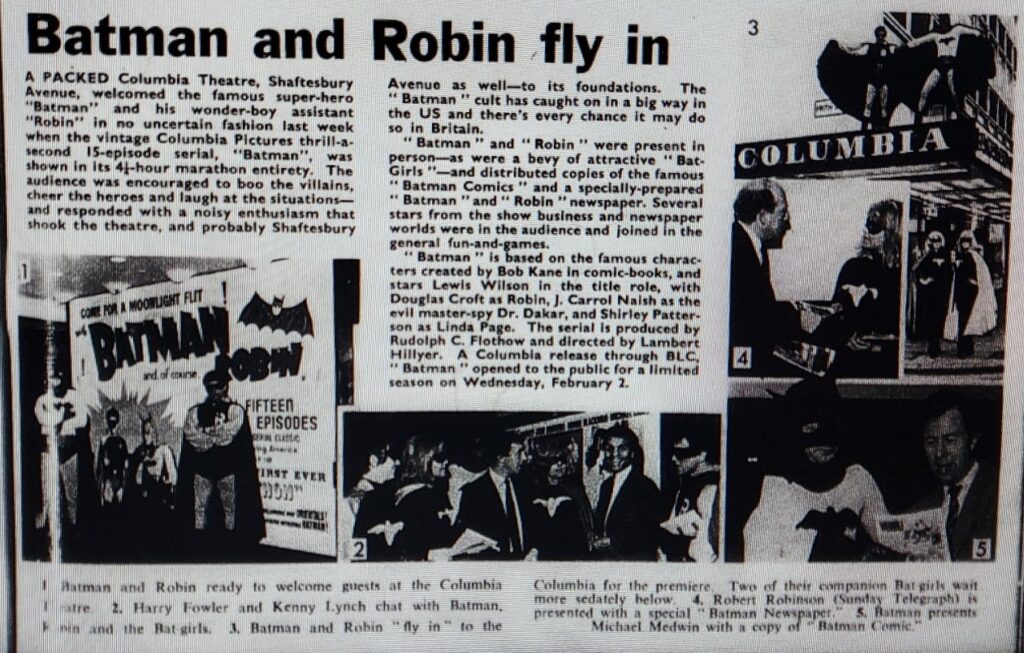

In the meantime, I leave you with a little time capsule of another era when Batman was super popular… In fact, he was so popular that people even went to the cinema to see his godawful 1943 serial (the one that was basically lampooned in Adam West’s TV show). I love all the scare quotes, suggesting the reporter’s embarassment and/or campy glee, especially when writing about the “Bat-Girls.”

Kinematograph Weekly, February 10, 1966

A deadly reminder that comics can be awesome!

Predator: Big Game

Miles to Go #1

God Is Dead #8