When I use the word ‘comics,’ it can mean different things. I can be talking about the medium itself, that is to say sequences of visibly still images that tell a story or develop an idea, including such remarkable literary works as Will Volley’s The Opportunity, Nate Powell’s Any Empire, or Gabriel Bá’s and Fábio Moon’s Daytripper, not to mention non-fiction books like Liv Strömquist’s Fruit of Knowledge. Or I can be referring to a specific kind of reading experience centered on gonzo weirdness and bodacious drawings in the service of a narrative committed to excite and entertain.

The latter can range from unimaginative dreck to transcendental masterpieces, but on a good day they’re at least enjoyable genre pieces that unrepentantly embrace schlocky elements in clever and/or amusing ways. Here are a few scattered thoughts on five comic books that feel just like, well, COMICS.

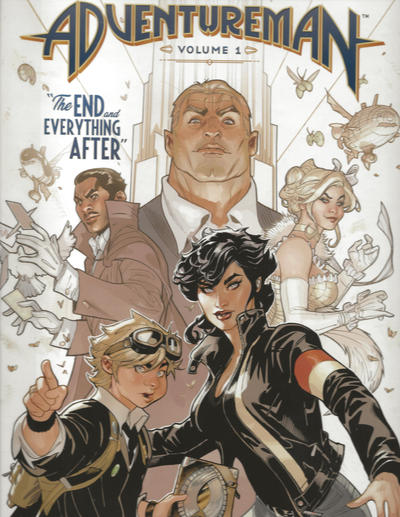

ADVENTUREMAN

Adventureman introduces an over-the-top version of Doc Savage and his team, then an even more over-the-top assortment of supervillains (led by Baron Bizarre), and then, after a bombastic fight between the two groups, we start to follow Claire Connell, a bored hearing-impaired single mother who works at a bookstore and believes she’s the least interesting member of her family… That is, until she starts investigating the fate of the supposedly fictitious Adventureman and gets wrapped up in an out-of-this-world romp full of art deco boobytraps and mind-bending spells! The result is both an ode to pulp heroes and an ode to New York (or, better yet, not to the actual pulps or to the city itself, but to their striking resonance over time).

Much of this has been done before, but Adventureman ultimately won me over due to Matt Fraction’s ability to come up with countless whimsical concepts (the Apocalypsydra? the Automaterror? the Oblivionists?), charming characters, and engrossingly elliptical storytelling, as well as – and above all – due to Terry and Rachel Dodson’s luscious artwork (he draws and colors, she inks). The depth of their layouts and all the slick, retro designs are nicely complemented by Clayton Cowles’ typically chameleonic lettering, ramping up the whole bouncy feel of the series. In particular, the way the protagonist increasingly irradiates wonder and enthusiasm is really something to behold…

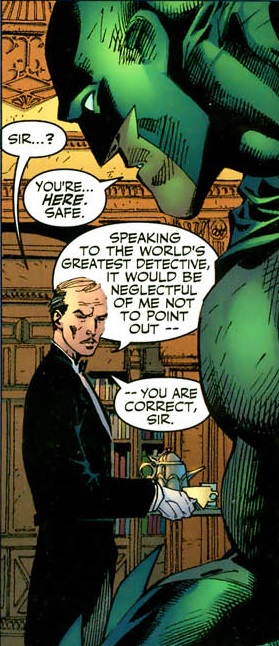

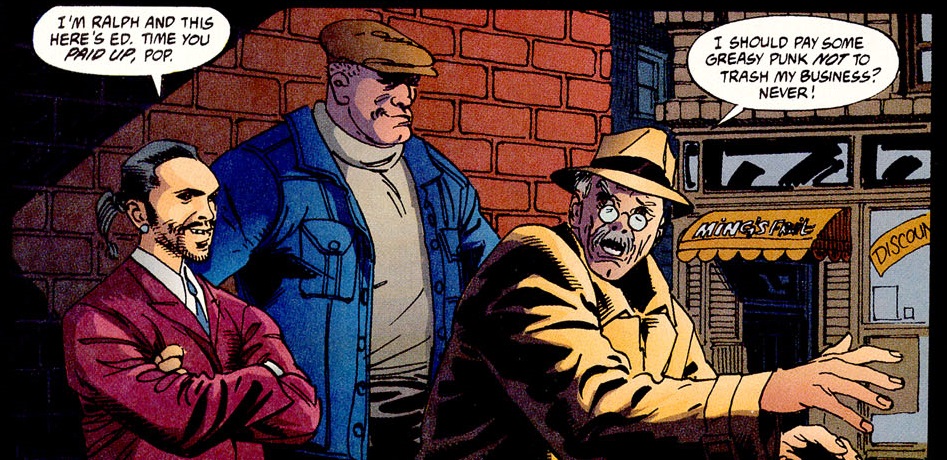

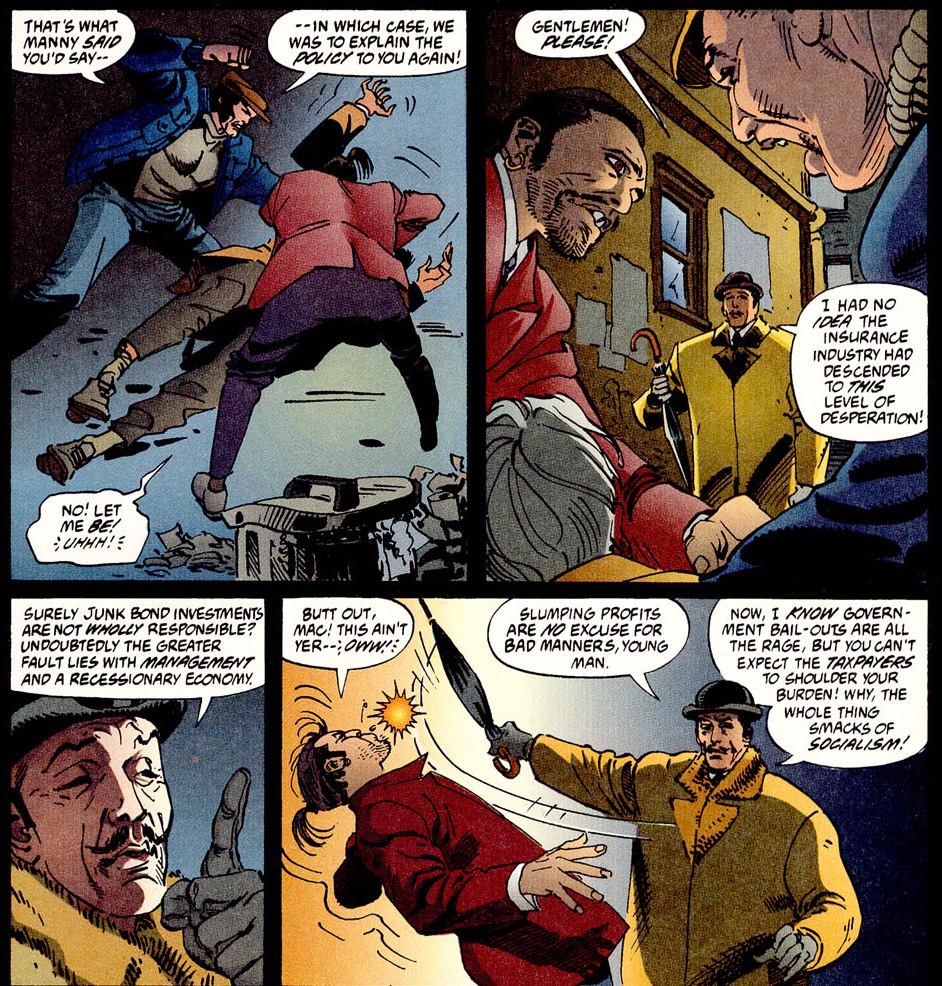

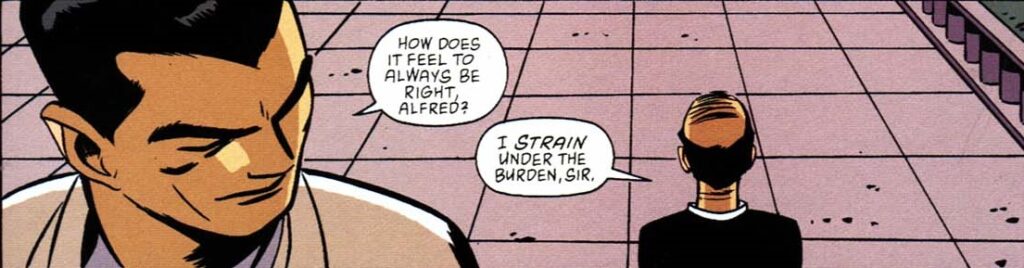

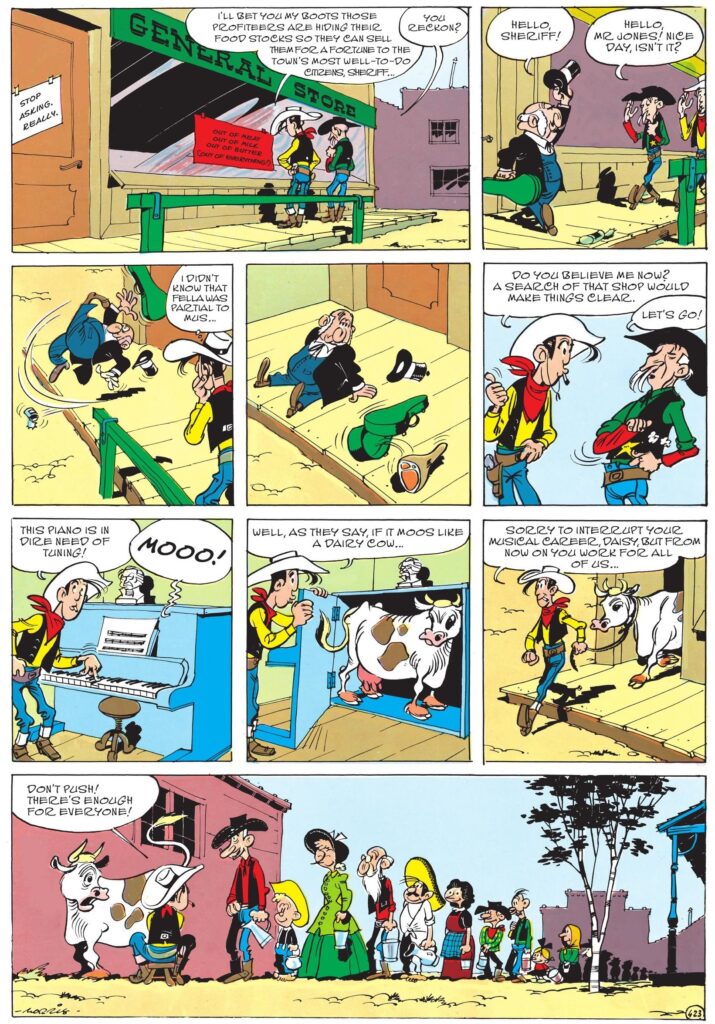

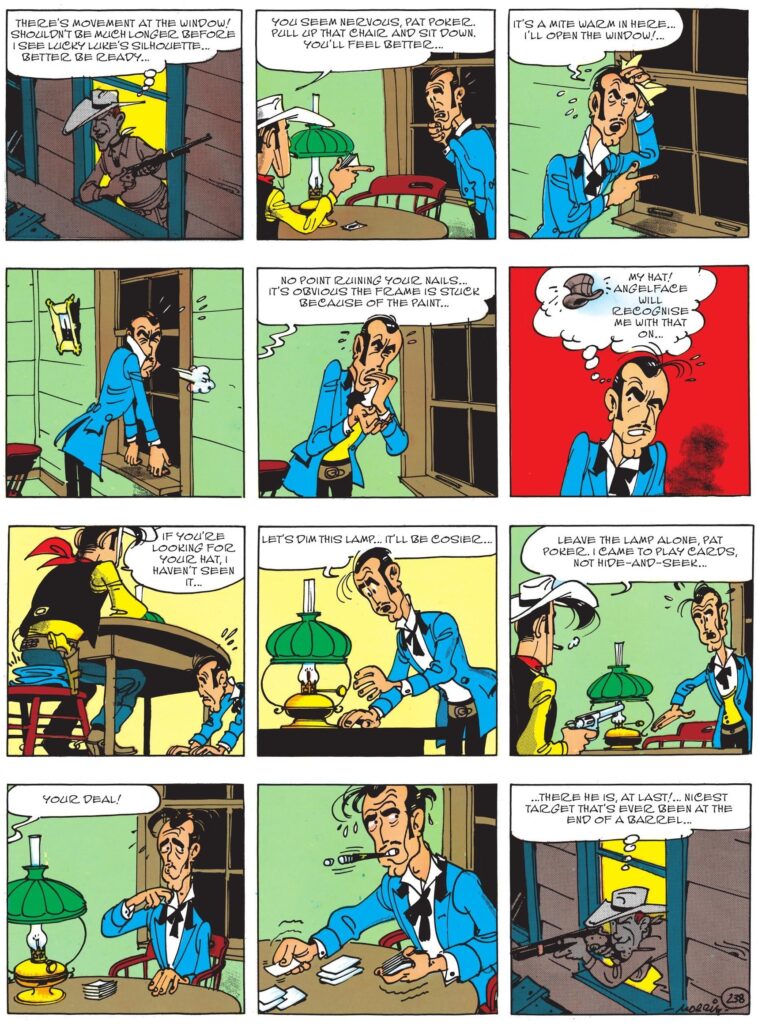

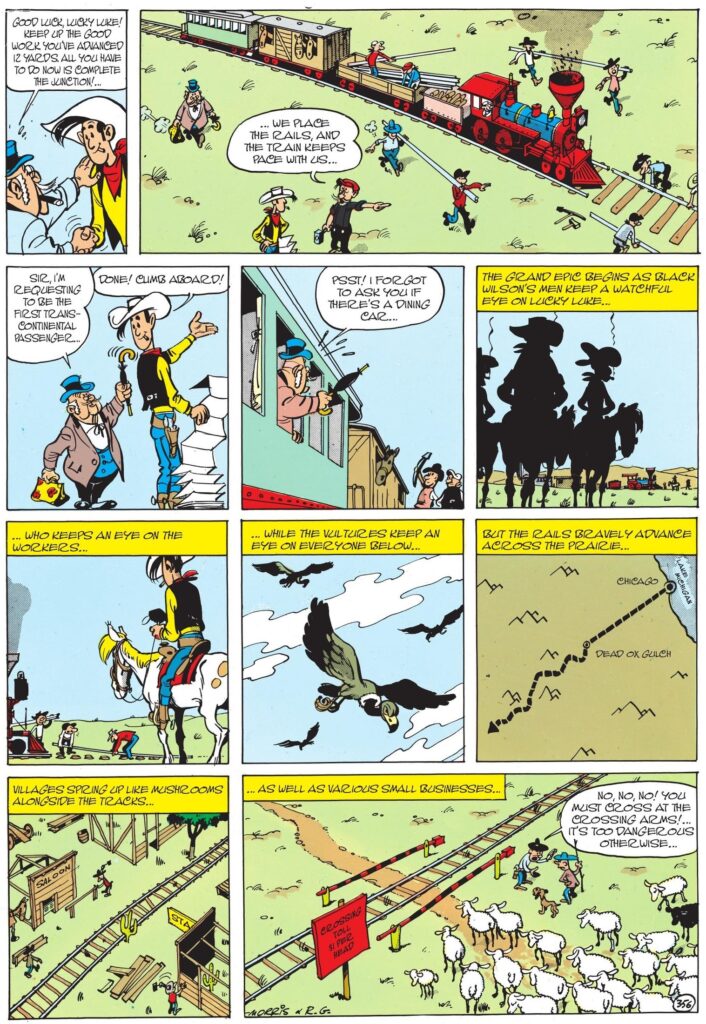

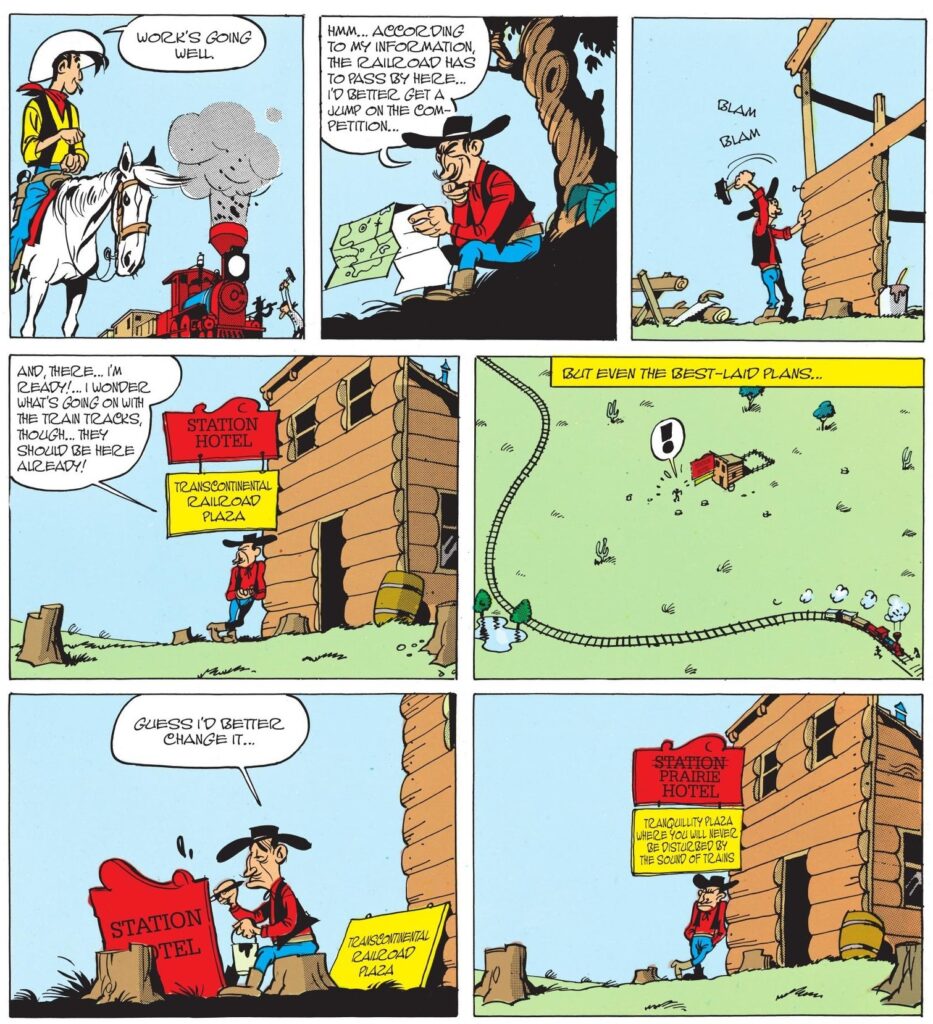

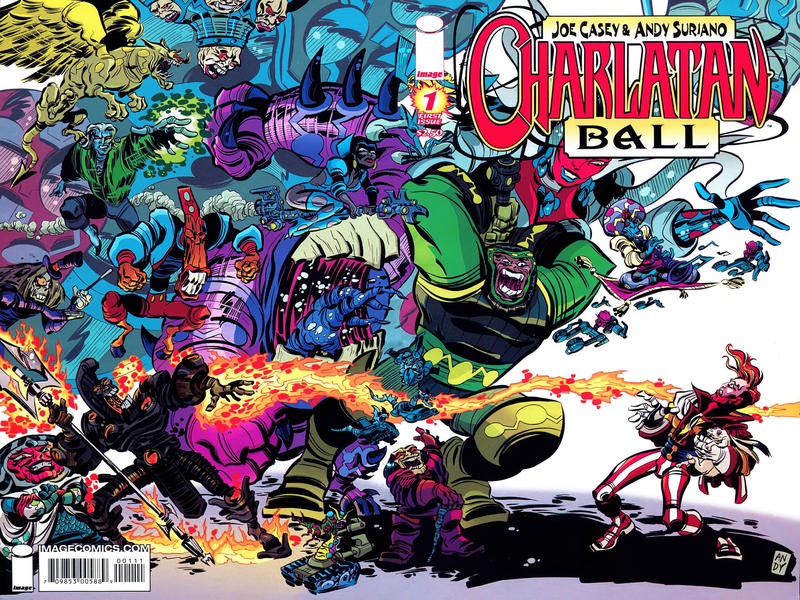

CHARLATAN BALL

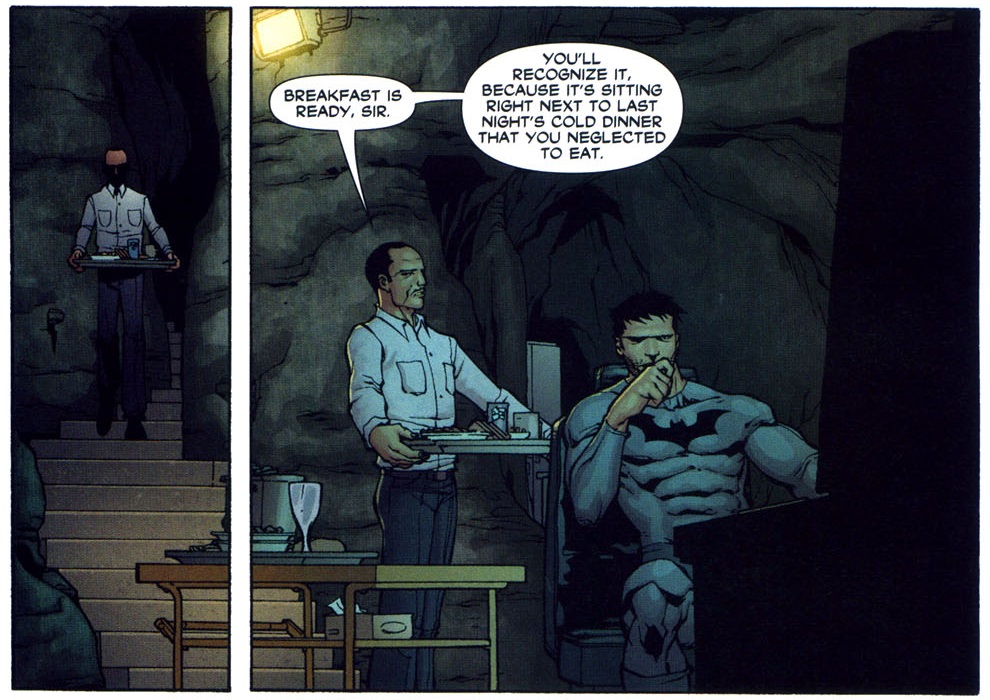

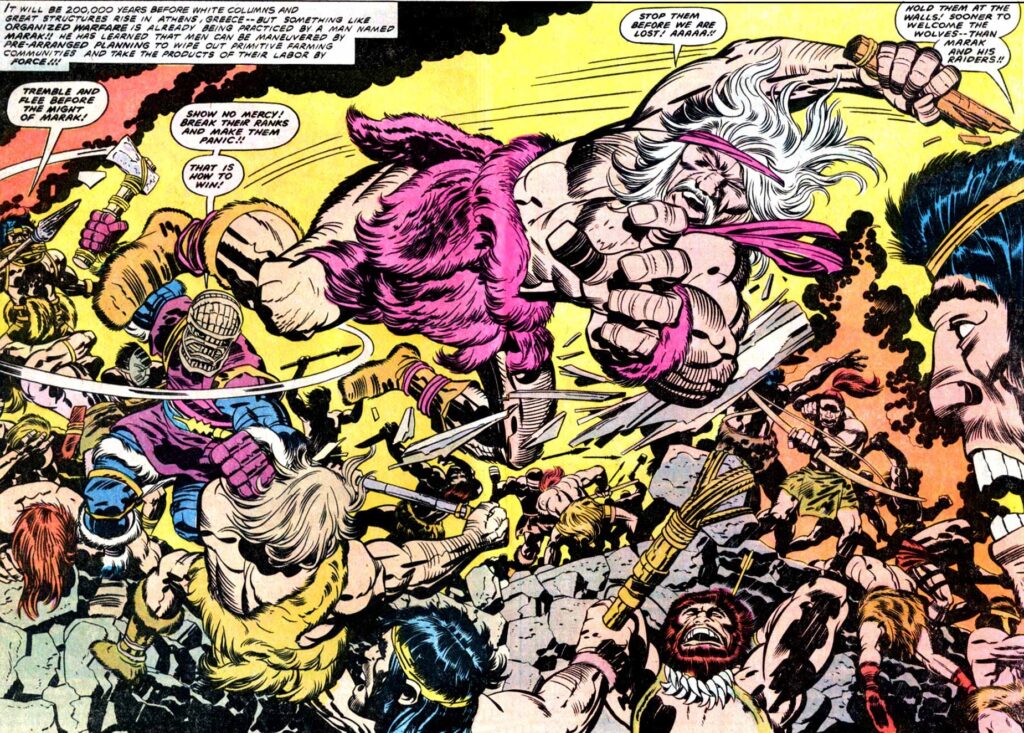

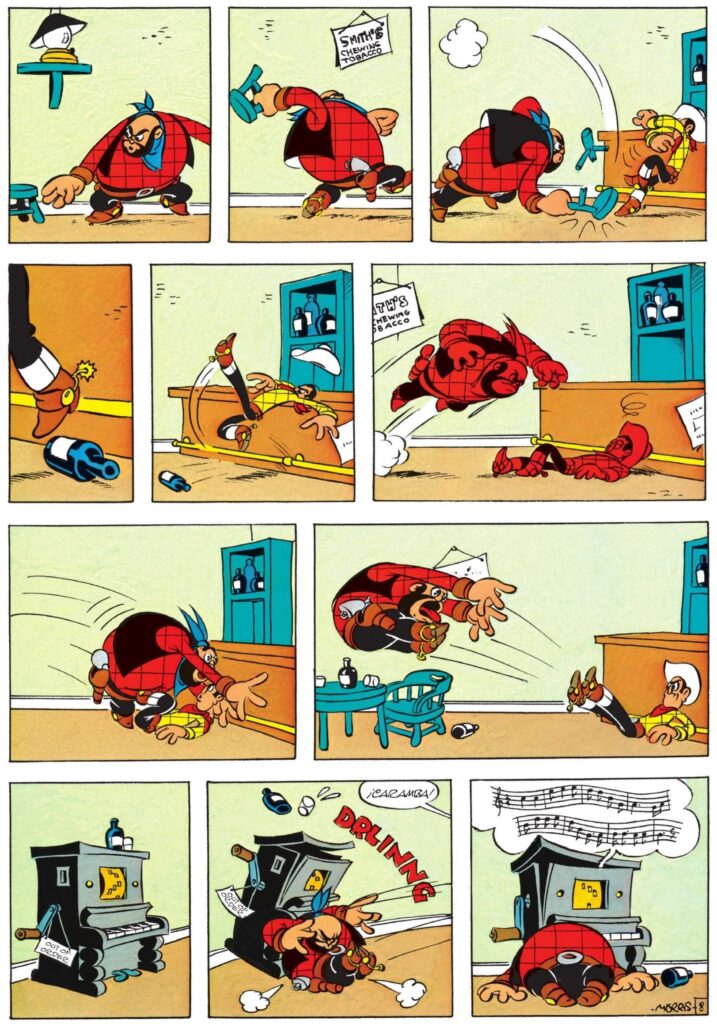

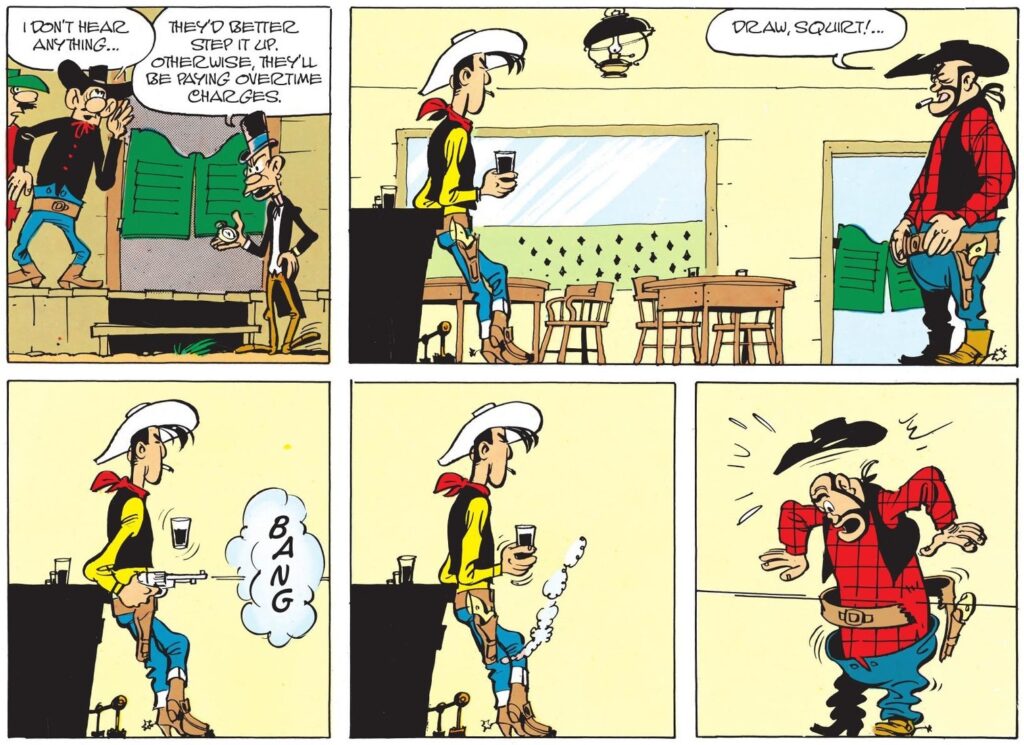

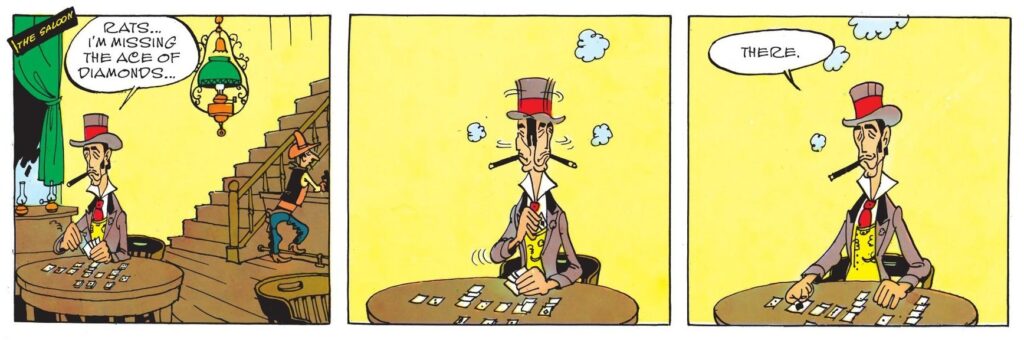

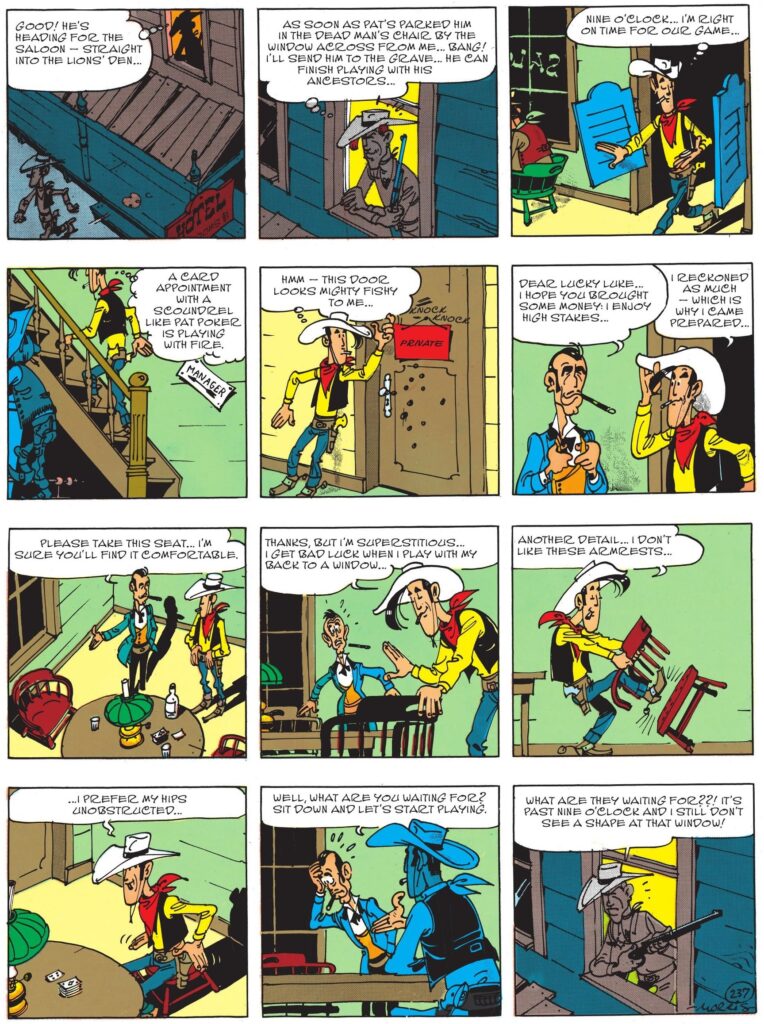

Joe Casey made much of his career trying to recapture the peculiar flavor of Jack Kirby’s manic surrealism, albeit with more of a hip, postmodern slant. One of the projects that took this approach particularly far was the 2008 mini-series Charlatan Ball, about a low-rent illusionist who gets transported into an outlandish fantasy world where he’s expected to enter – along with his mutated rabbit – a deadly competition against mega-powerful sorcerers.

Because the story was meant to continue in later installments that haven’t materialized (yet?), the book ends on a somewhat unresolved note, but it doesn’t really matter, as ultimately the purpose of the paper-thin plot is merely to secure a loose structure among the chaotic slugfests. In other words, while Casey comes up with a quirky cast (including a monster called Hellion Keller, the Blind Destructor – get it?), amusing narrative captions, and more than a dash of metafiction (even name-dropping Rogan Gosh), the true star of the comic is the artwork of co-creator Andy Suriano, who nails Kirbyesque designs and action scenes while somehow making them even cartoonier. Suriano’s inking, which is so expressive that it seems almost calligraphic, works particularly well with Marc Letzmann’s explosive colors and Rus Wooton’s spirited lettering.

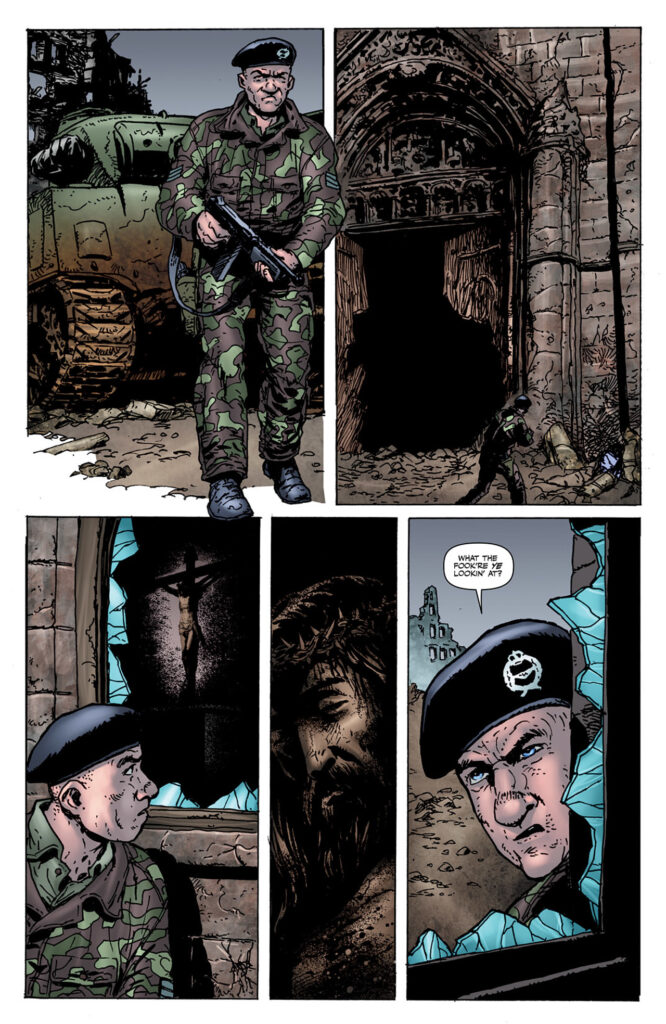

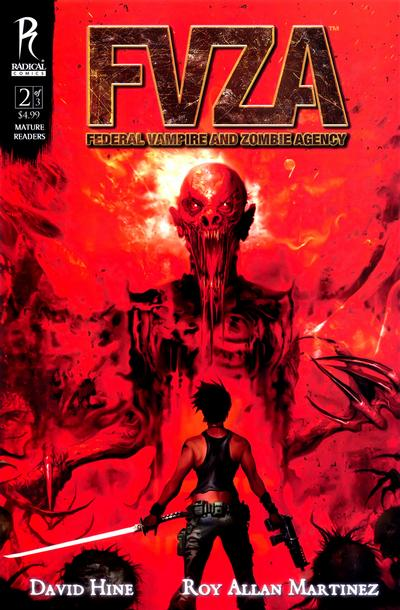

FVZA: FEDERAL VAMPIRE AND ZOMBIE AGENCY

So, not only are zombies and vampires real, but they were treated as viral diseases until the mid-1970s, when a specialized federal agency apparently managed to eradicate them in the United States… until now! The detailed alternate history that makes up the bulk of FVZA’s backstory was actually developed in a site created by Richard S. Dargan, so this 2009 mini-series is technically an adaptation (or a spin-off?) of a website, which is a rare path. What the reliable David Hine brings to the table is both solid characterization and some suitably gnarly imagery, not to mention a then-topical concern with bio-terrorism (which now reads as a topical concern with epidemiological threats).

Kinsun Loh and Jerry Choo paint the comic in Radical’s house style, i.e. an ultrarealistic digital coloring process that’s not for all tastes (it usually isn’t for mine), but which doesn’t clash with the naturalistic figures drawn by Roy Allan Martinez and Wayne Nichols. Honestly, I would’ve preferred more fluid-looking artwork rather than something that could pass for a photonovel… Still, even if the images feel too static, at least the book lives up to its promise by delivering quite a fair share of creepy and gory horror set pieces.

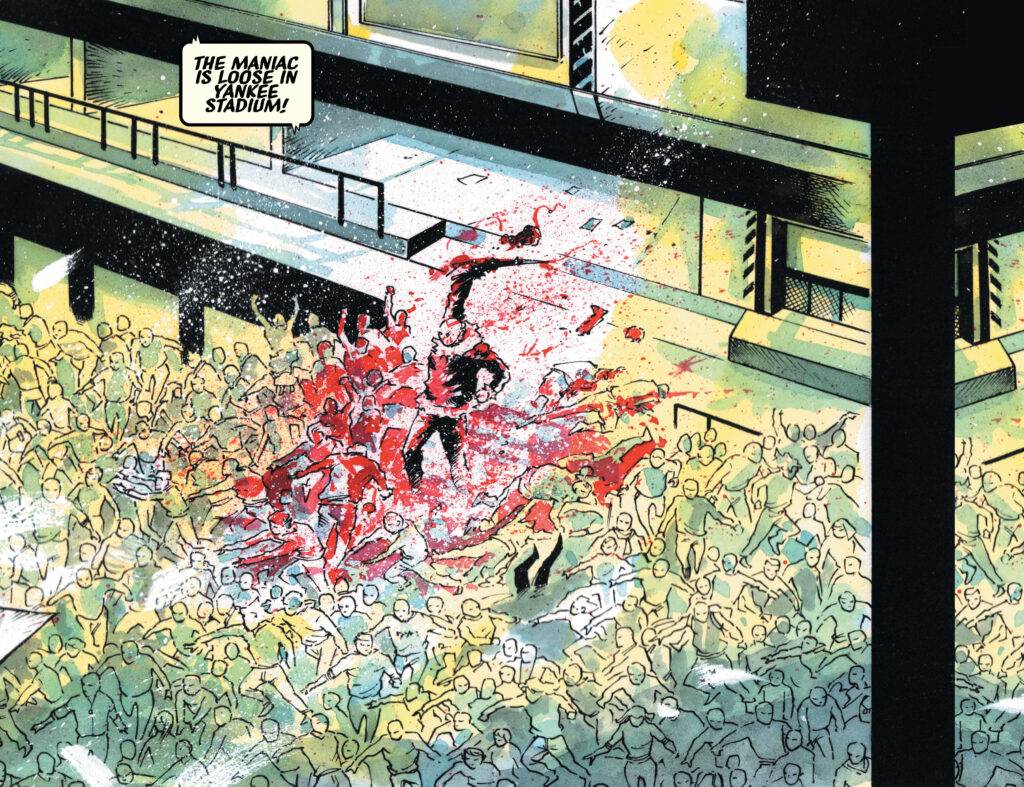

THE NINJETTES

The latest reboot of The Ninjettes completely overhauled the original premise (which was little more than ‘team of killers dressed in kogal schoolgirl uniforms’ to begin with) by having a secret government program take away teenagers predicted to be on the verge of committing school massacres and then pit them against each other in the middle of nowhere. A spin on the likes of Battle Royale and The Hunger Games (not to mention Lord of the Flies), this is as tasteless and immoral a black comedy as it sounds, with a dozen girls bickering – ironically resorting to ‘woke’ lingo – and bloodily slaughtering each other while wearing fetishistic uniforms (even if Joseph Cooper’s and Dearbhla Kelly’s art and colors help restrain the sexualization of teens inherent to The Ninjettes’ committedly trashy vibe). If this were a movie, there’d a dozen indignant op ed pieces about it, but comics get away with this sort of stuff all the time… And Fred Van Lente is one of those writers who can actually pull off a fine balance between, on the one hand, the exuberance of brazen exploitation and, on the other, smart character work and a knowing approach to these tropes, somehow mocking and indulging in them at the same time.

The Ninjettes started off as a throwaway gag in Garth Ennis’ original Jennifer Blood series and, like everything else in that godawful run, was eventually elevated to undeserved brilliance during Al Ewing’s subsequent stint on the property. After years adrift, the franchise only recently recovered from Ewing’s departure, as Van Lente has given it a sudden injection of off-the-charts energy. That said, to appreciate his new take on the Ninjettes you don’t have to know anything about their predecessors or about any of the comics starring Jennifer Blood. You just have to set aside any sense of shame and embrace all the hyper-violent, outrageous grindhouse vibe.

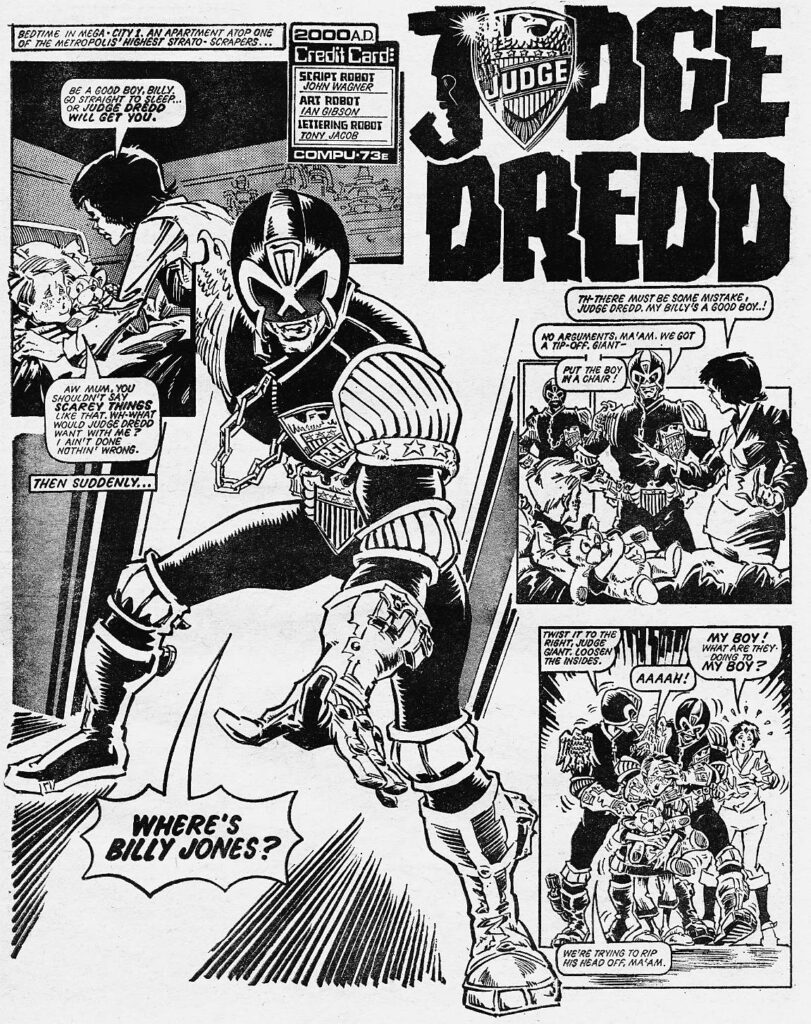

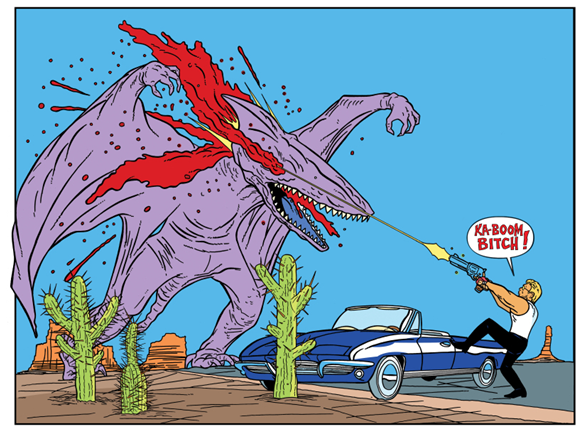

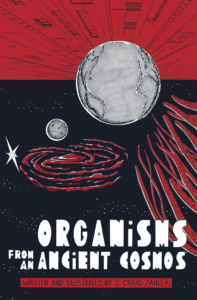

ORGANISMS FROM AN ANCIENT COSMOS

Having masterfully reworked pulpy genres in films like the horror western Bone Tomahawk and the bad cop/heist thriller Dragged Across Concrete, in his second graphic novel S. Craig Zahler applies his signature brand of vicious storytelling to an alien invasion saga. You may think you know how these stories go, but don’t be so sure… While the tone is more tongue-in-cheek than usual, Zahler’s plotting feels much more ambitious, as he keeps broadening the book’s scope and stakes, letting the narrative organically expand into new and surprising directions (including a lengthy detour into prison drama).

Not only does the naïve-looking black & white artwork intensify the deadpan humor, but the ensuing visual style is also somewhat reminiscent of 1950s’ B-movies and Al Feldstein comics. If that era’s science fiction channeled Cold War fears of invasion, radiation, and nuclear apocalypse, however, 2022’s Organisms from an Ancient Cosmos updates the tropes’ allegorical potential to reflect current anxieties around terrorism, the covid pandemic, and the tense, suspicious, competitive relationship between the US and China. Nasty fun.