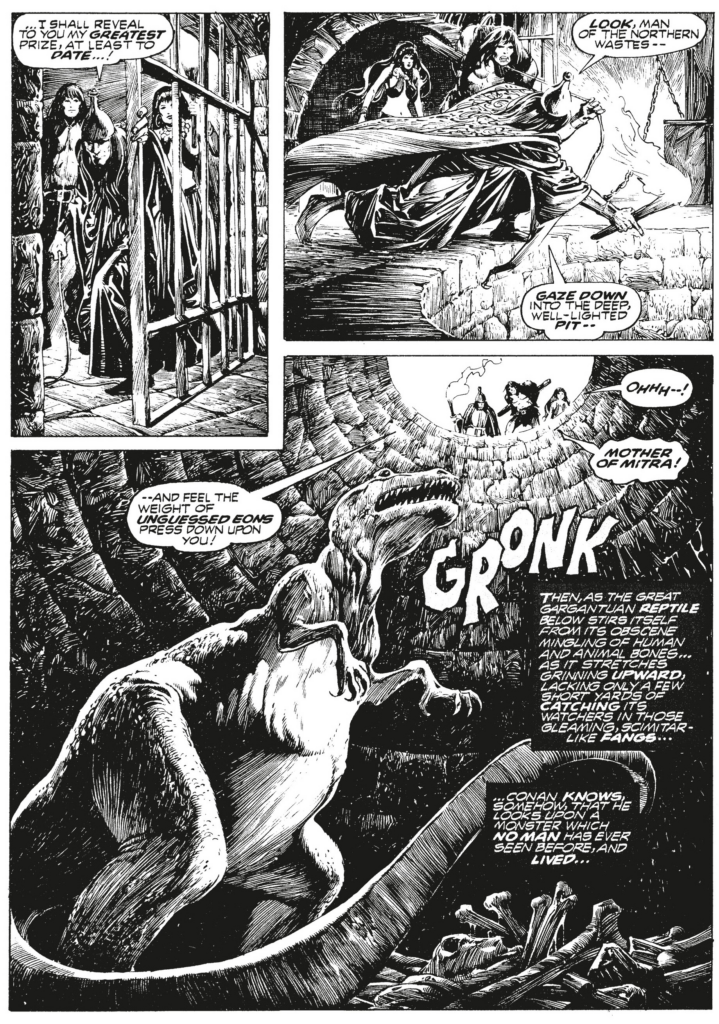

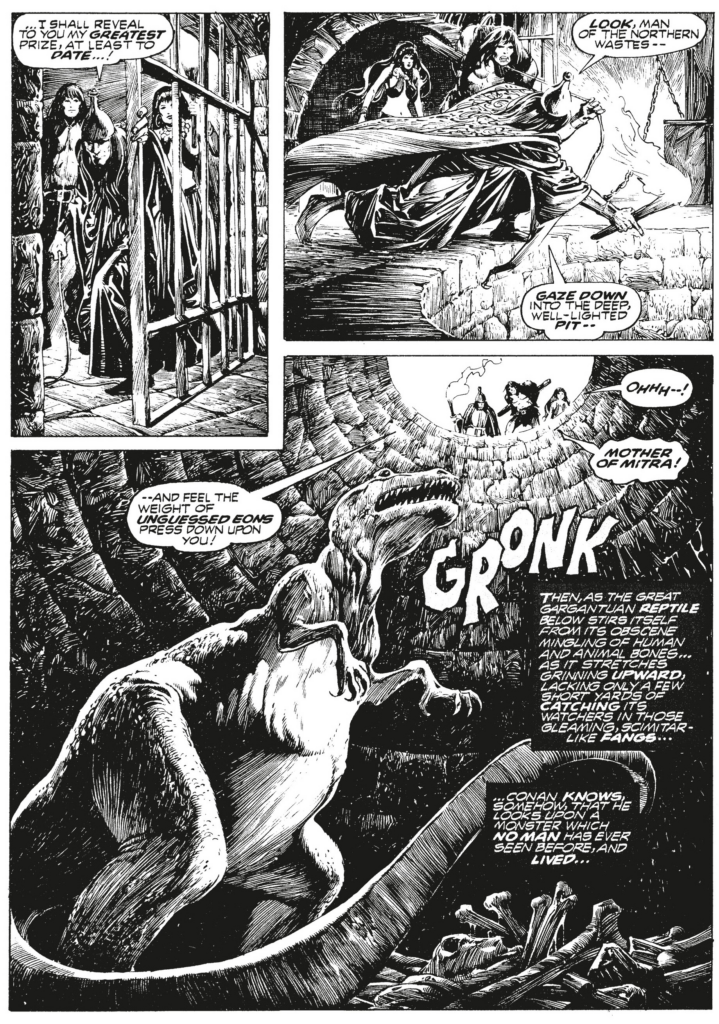

The type of sequence that made me fall hopelessly in love with Marvel’s black-and-white magazines from the 1970s:

The Savage Sword of Conan the Barbarian #7

The type of sequence that made me fall hopelessly in love with Marvel’s black-and-white magazines from the 1970s:

The Savage Sword of Conan the Barbarian #7

I’m setting aside splash pages, for a bit. Instead, in February, these weekly reminders that comics can be awesome will be excerpts of sequences that have stuck in my mind.

Over the past years one of my ‘guilty’ pleasures has been W0rldtr33, a hysterically trashy horror series that, at one point, actually contained the line: ‘she’s been possessed by a malevolent force from the evil internet that lives beneath the internet.’ The comic has a logic-be-damned, quasi-punk satirical approach to horror, with a near-apocalyptic pitch and an in-yer-face attitude that feel well-suited to our near-apocalyptic and in-yer-face times – indeed, it’s not entirely unlike Coralie Fargeat’s The Substance. And yet, in the midst of all the gore, of the very silly sci-fi (where a world without internet seems unimaginably dystopic, even though it wasn’t all that long ago…), and of what I assume is some kind of allegory for the far-right radicalization of youth via social media, we got this sweet sequence of pre-arson bonding:

W0rldtr33 #2

I haven’t written about films in 2025, although I’m putting together a couple of ambitious lists that should come out later in the year… In the meantime, if, like me, you feel the current offer of crime movies, no matter how slick, has been generally bland and predictable, why not have some fun with this potpourri of slightly odd – if not downright idiosyncratic – and captivatingly unbalanced thrillers from the past?

COPLAN SAVES HIS SKIN (1968)

I’m a sucker for films that take you on a ride where, even if you can sort of guess where you’re heading, you keep getting surprised by what you find along the way. It’s the case with this strange revenge yarn about a French spy in Turkey, which somehow moves from international intrigue into a gothic horror piece with a brutal showdown, yet it pulls this off through a quasi-oneiric atmosphere that shamelessly trumps logic (in part achieved through fluid camera movements, rich location shooting, and a protagonist with a constant no-nonsense expression). Among France’s various attempts to emulate James Bond, the eclectic movies about the ruthless agent Francis Coplan came increasingly close to 007’s fantastic adventure vibe, but this last installment pushed things so far that it transcended the series’ inspiration (perhaps because it wasn’t originally intended as a Coplan picture at all!), culminating in a truly eerie – and even lyrical – place.

EXPECT THE UNEXPECTED (1998)

What if you took a violent Hong Kong crime thriller about a police unit hunting down some fugitives and fused it not only with pitch-black humor, but also with a romcom subplot? Expect the Unexpected damn well lives up to its title: one moment your heart is pounding with adrenaline, then you find yourself laughing at the kookiest characters, then all of sudden it cuts to the most horrific thing you’ve ever seen onscreen, and before you know it you get a nihilistic ending that comes straight out of left field. Needless to say, the genre hybridity and uneven tone are part of what makes this film so great, as it restlessly refuses to let itself be pinned down.

FORTY EIGHT HOURS TO ACAPULCO (1967)

A businessman sends a young guy to Rome to buy some secret documents regarding an industrial deal with Romania, but as soon as he hits the road the guy – steered by his sexy lover – starts reconsidering the plan. This was the first film by German indie director Klaus Lemke, who basically put together a couple of bucks and managed to shoot something that works both as a stylish neo-noir *and* as a New Wave tribute to American cinema, music, and comics (there is even a millionaire called Wayne!). A youthful, moody, and spellbinding treat.

KISS KISS BANG BANG (2005)

Robert Downey Jr. plays a smartass, fast-talking petty thief who unexpectedly lands an acting gig playing a detective and, even more unexpectedly, finds himself embroiled in an actual (violent and labyrinthic) detective story in LA while getting lessons from an actual (gay and sarcastic) private investigator. After years of scripting buddy action comedies such as Lethal Weapon, The Last Boy Scout, and Last Action Hero, Shane Black finally got to direct his own movie and thus bring to the screen a more unfiltered version of his madcap sensibility, with the result rivaling Expect the Unexpected when it comes to frantic tonal shifts. On top of the pulpy mystery intrigue and of the quippy screwball black comedy laden with sex and gay jokes, we get layers of metafiction, not only within the story (Hollywood satire, a pulpy mystery series inspiring the actual crimes…), but also in its very presentation (Chandleresque chapter titles, a self-reflexive voice-over mocking clichés and pointing out plot devices…). Val Kilmer’s deadpan performance as the PI goes a long way in terms of counterbalancing the protagonist’s homophobia, although Michelle Monaghan ultimately steals the show by committedly embracing all of the shifting tones: funny, sexy, tragic, clever, romantic, and even somewhat of an action hero, when the film calls for it.

THE NARCO MEN (1968)

In The Narco Men, a drug lord hires ex-con Harry Bell to investigate the hijacking of a heroin shipment, which takes him around the Mediterranean while lurid colors fill the screen and kickass beats pound in the soundtrack. Despite being made in Francoist Spain, this cool, gritty, action-packed crime yarn is surprisingly countercultural: not only is Bell a nasty anti-hero working outside the law, but his love interest is a hippie whose youthful flower power exuberance stands in stark contrast to all the surrounding violence and downbeat cynicism.

VIRTUE (1932)

A mouthy, take-no-shit New York streetwalker (played by the awesome Carole Lombard) tries to move on from sex work and to build a new life despite her lover’s prejudices, but damn fate keeps conspiring against her. Made during those wild years before the rise of Hollywood’s censors, the picture is set in a seedy underworld of pimping, prostitution, and small-time cons, shown with a relatively frank and non-judgmental attitude even as it reflects the era’s values in various ways. On the surface, Virtue is a brisky romantic melodrama with dynamic camerawork and snappy dialogue, yet there are so many twists, crimes, and hardboiled lines along the way (especially in the final stretch) that it should also appeal to anyone interested in the precursors of film noir.

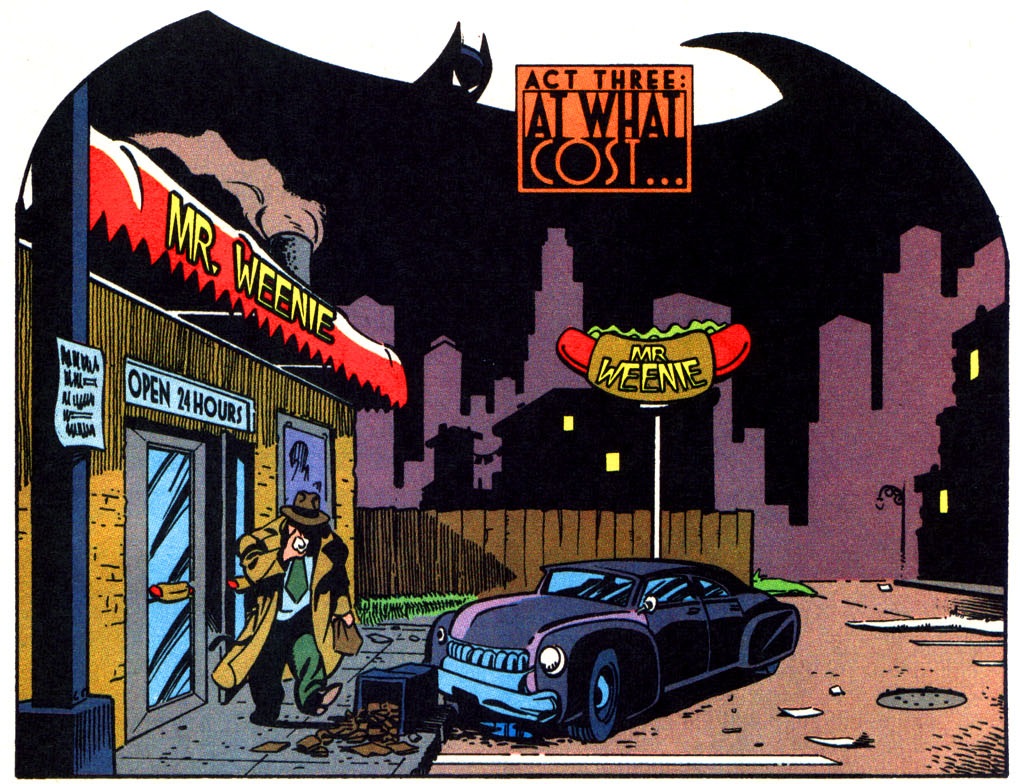

With 2025 already well on the way to becoming a terrifying year, even by recent standards, here is January’s final reminder that comic book splash pages can be awesome:

Casanova: Acedia #4

Assassin Nation #4

Dead Drop #3

The Batman Adventures #33

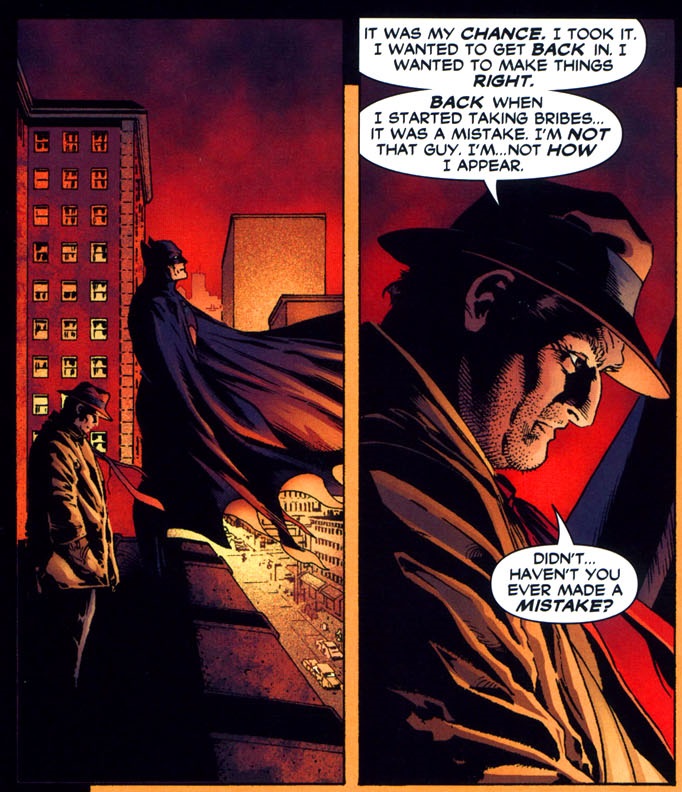

Picking up from where I left off last month, let’s have a further look at the evolution of Gotham City’s gruffiest, scruffiest police detective, Harvey Bullock.

In the 1990s, Bullock gained prominence as a memorable supporting player in the very cool Batman: The Animated Series. Developed by Bruce Timm, Paul Dini, and Mitch Brian, that show streamlined the best elements accumulated over decades of Batman stories into their neatest form – and Harvey Bullock was no exception. The show’s bible nailed him in a nutshell: ‘Believing his badge is a legal license to break the rules, he resents Batman as an unauthorized meddler who is muscling in on his territory. Down deep, he’s probably irked that nobody screams “police brutality” at Batman, like they do to him.’

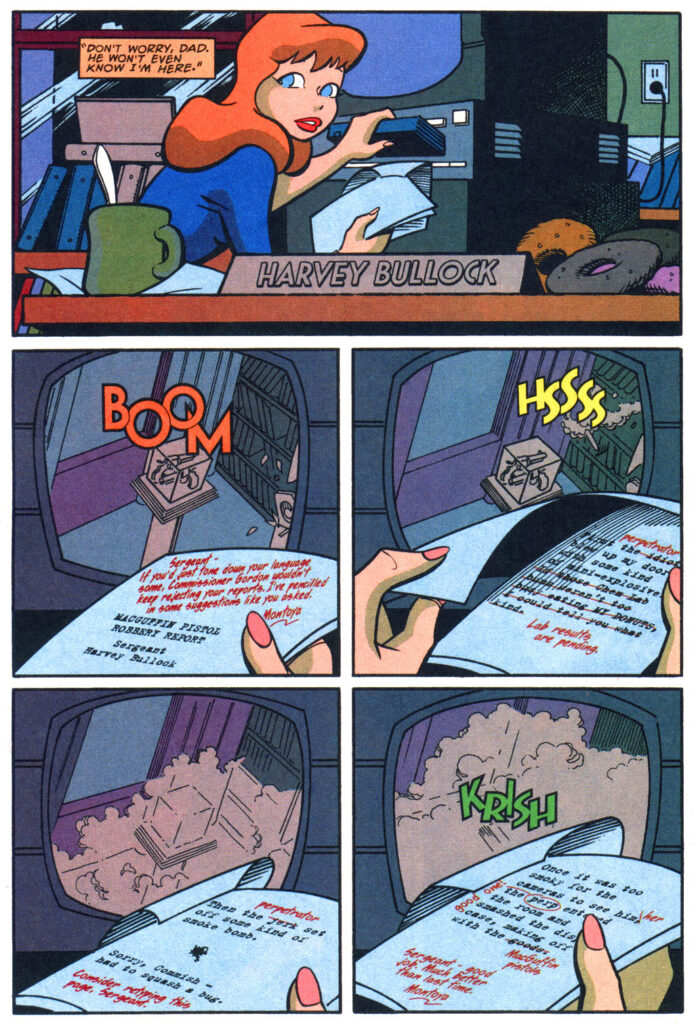

Niftily redesigned through Bruce Timm’s smooth style and voiced by the great character actor Robert Costanzo, the animated Harvey Bullock was damn funny. In fact, he made such a strong impression that the spin-off comic series The Batman Adventures could afford to get away with jokes based on readers’ mere awareness of Bullock’s abrasive personality:

The Batman Adventures #26

Initially, this take on the character was not too far from the one Chuck Dixon began developing in Detective Comics at the same time (in what was perhaps an editorially coordinated move). Basically, Harvey Bullock came from a grown-up film noir world and sounded hilariously resentful over the fact that he had to put up with all the childish, goofy elements of the Caped Crusader’s universe (not least the colorful themed villains). Another way to look at it is that his demeanor was everything that’s unappealing about cops in real life and so perversely appealing in fiction.

You could still see traces of it by the end of the decade, during the ‘No Man’s Land’ crossover, when Bullock was one of the citizens who stayed behind in Gotham even after the city was abandoned by the US government and became a lawless danger zone:

Batman: No Man’s Land #1

In 2001, however, the official DCU version of Harvey Bullock finally went one step too far beyond the law, courtesy of writer Greg Rucka. After Commissioner James Gordon was shot by Jordan Rich, a disgruntled former officer hiding under a new identity via the witness protection programme, a loyal Bullock retaliated by tipping the Mob about Rich’s location, thus facilitating the shooter’s murder by vengeful criminals. When confronted about this, a few months later, Bullock resigned in disgrace.

The easy political reading here is that the liberal Rucka provided actual consequences to the sort of bad cop attitude the conservative Dixon cynically accepted (or at least played for laughs). Yet I think this development was not only consistent with Bullock’s characterization, but it even made him more interesting at various levels.

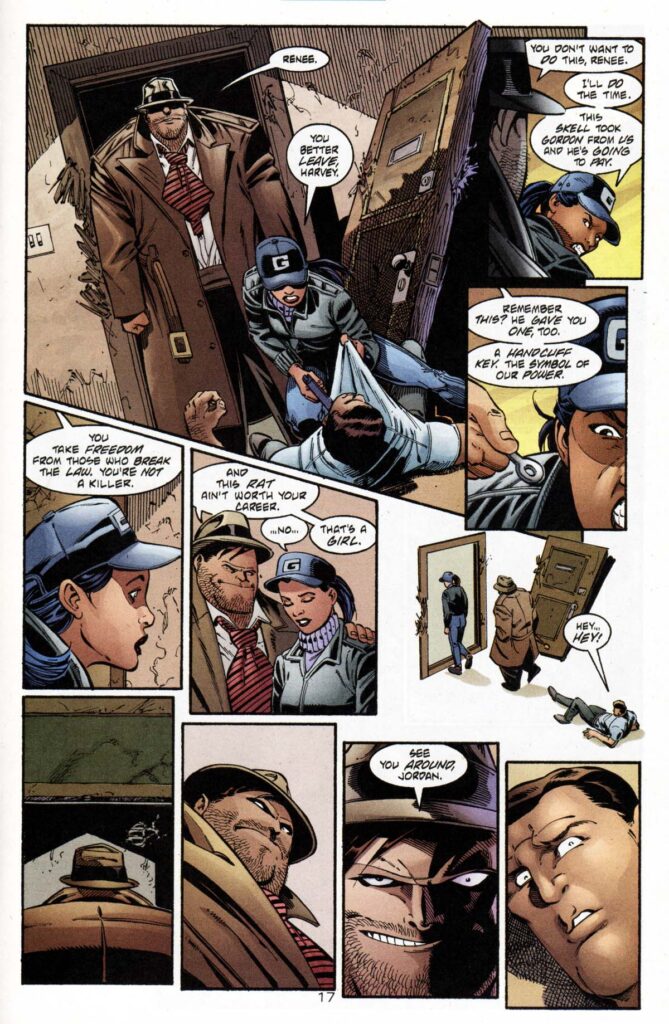

For one thing, Rucka wrote it in a way that gave Bullock a peculiar kind of dignity, namely by leaning into his respect and affection both for Gordon and for his partner, Renee Montoya. Before learning what he was up to, we saw Bullock prevent Montoya from pursing her own deadly revenge quest against Jordan Rich, thus protecting her without admitting as much:

Gotham Knights #13

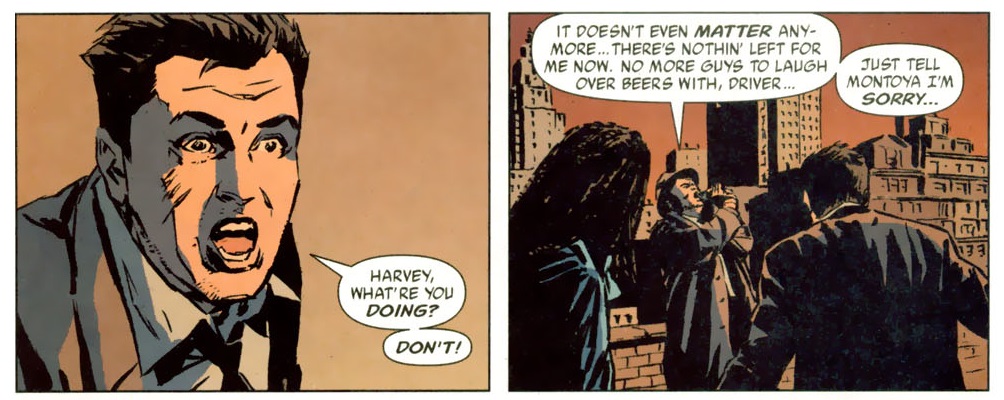

Issues later, when the payoff finally came, Greg Rucka let Harvey Bullock walk out, of his own volition, rather than send him to prison. What’s more, Bullock’s goodbye gesture to Renee Montoya was not only a nice callback to the scene above, but also a begrudging admission that he realized he had crossed the ultimate line and was unworthy of the trust Commissioner Gordon had placed in him…

Detective Comics #762

Although we now saw much, much less of Harvey Bullock on the page, which was a shame, I love the fact that his legacy continued to loom over Batman comics. Even in his absence, Bullock continued to be a cast member in spirit.

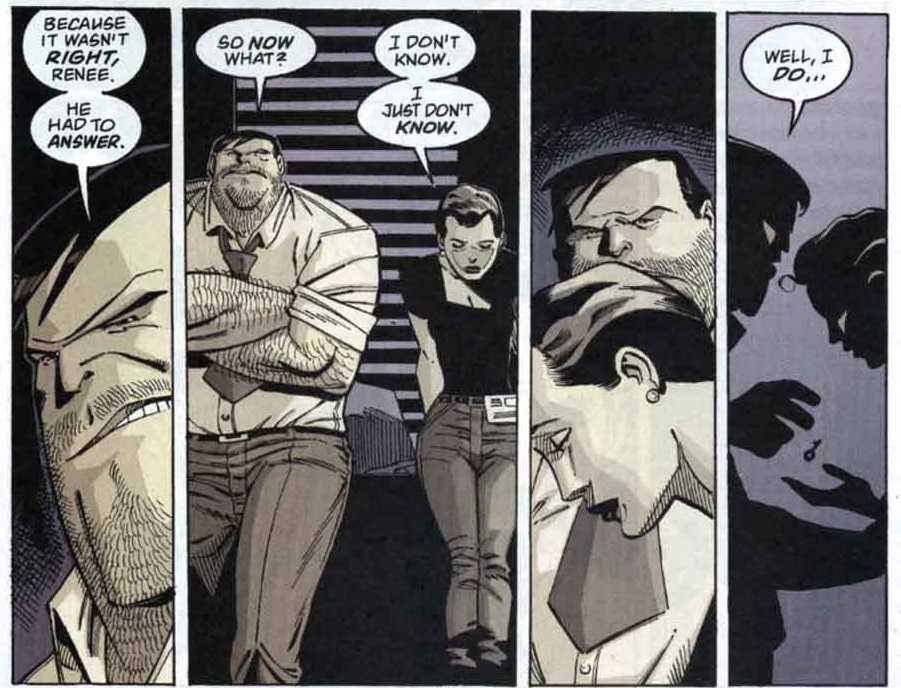

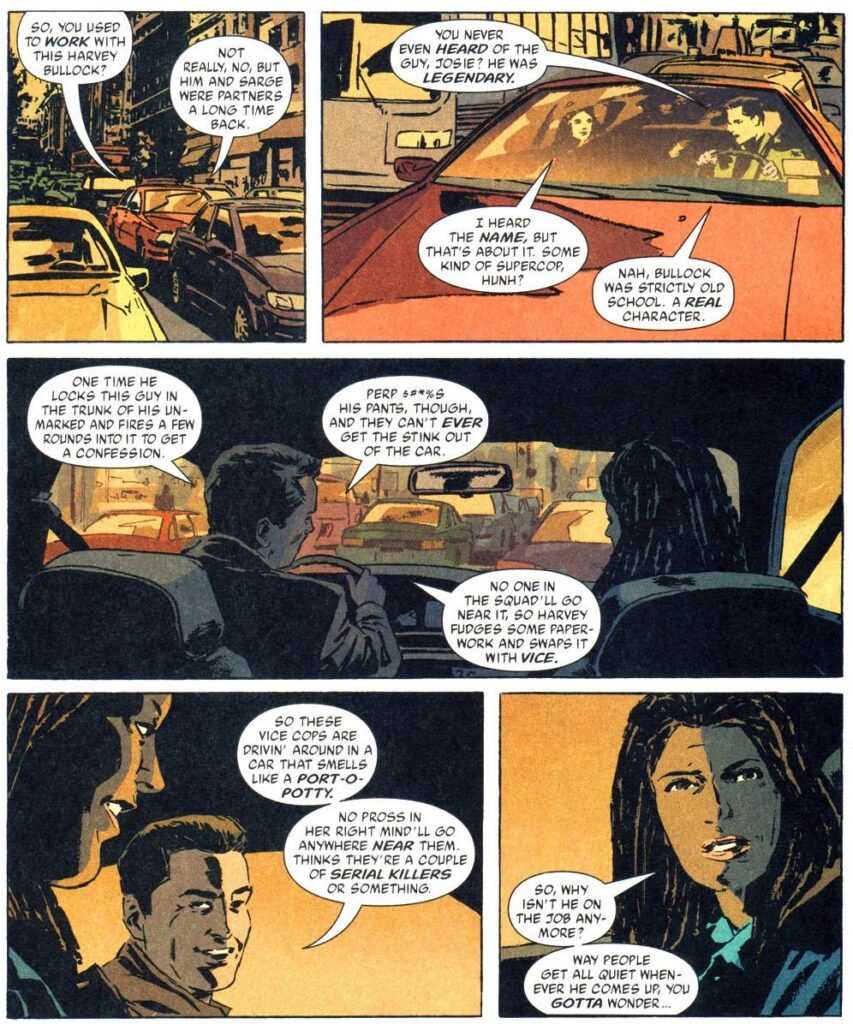

When Greg Rucka and Ed Brubaker launched the awesome police procedural Gotham Central, in 2003, they reminded readers that the rest of the Major Crimes Unit was still marked by the memory of what had happened to Bullock.

Gotham Central #4

The last ‘silent’ panel speaks volumes, right?

This issue was actually written by Ed Brubaker, who did the best callbacks to Harvey Bullock in his scripts for the series. Perhaps Greg Rucka felt he had already completed Bullock’s arc and didn’t have much to add. Or maybe it was just Brubaker’s own passion for fucked up characters fallen from grace, coupled with his knack for casual banter among pros…

Gotham Central #20

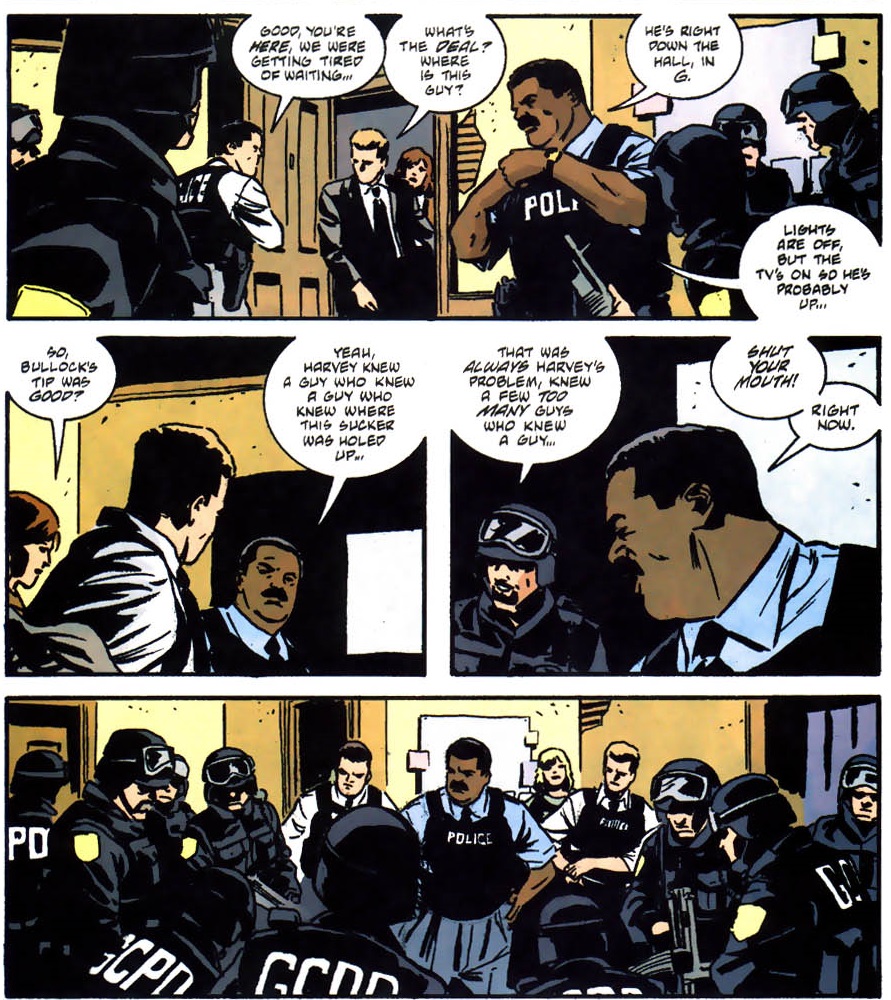

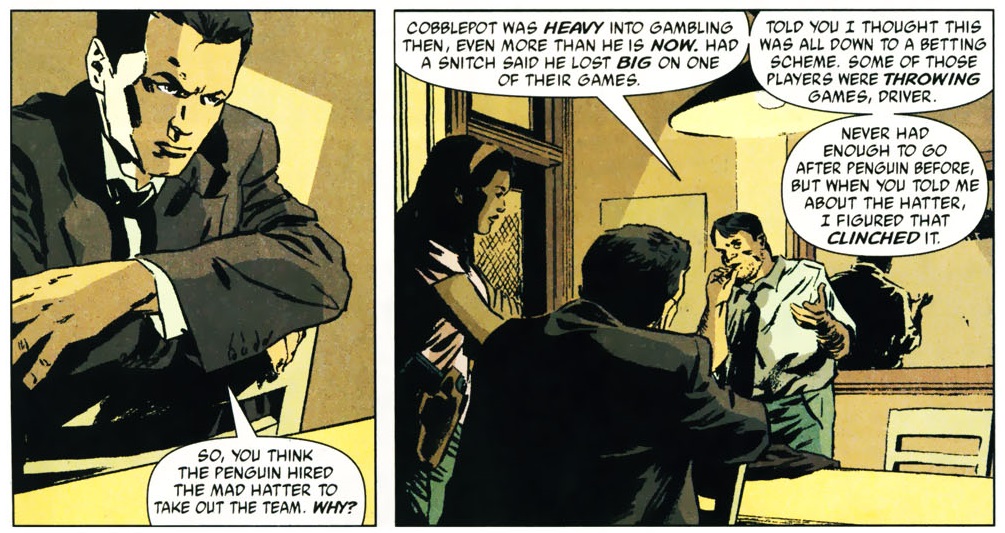

In any case, in 2004, Ed Brubaker finally brought Harvey Bullock back, in body as well as in spirit, for ‘Unresolved,’ an amazing Gotham Central arc in which a couple of cops pick up an old Bullock case and go to him for help.

I’m on the record as considering Brubaker’s work on Batman comics (hell, his comics work in general) as hit-and-miss, but this story is definitely a hit. Everything about ‘Unresolved’ is prime Brubaker doing what he does best, with smart, affecting plot, dialogue, and characterization all around. And when Bullock showed up again after all the buildup, it certainly made the wait worthwhile.

Gotham Central #21

Honestly, I would’ve been fine with the odd Harvey Bullock cameo like this, helping out in an investigation every once in a while, popping up as a cop in flashbacks and as an ex-cop in the present, perhaps even teaming up with private eyes like Slam Bradley or Joe Potato.

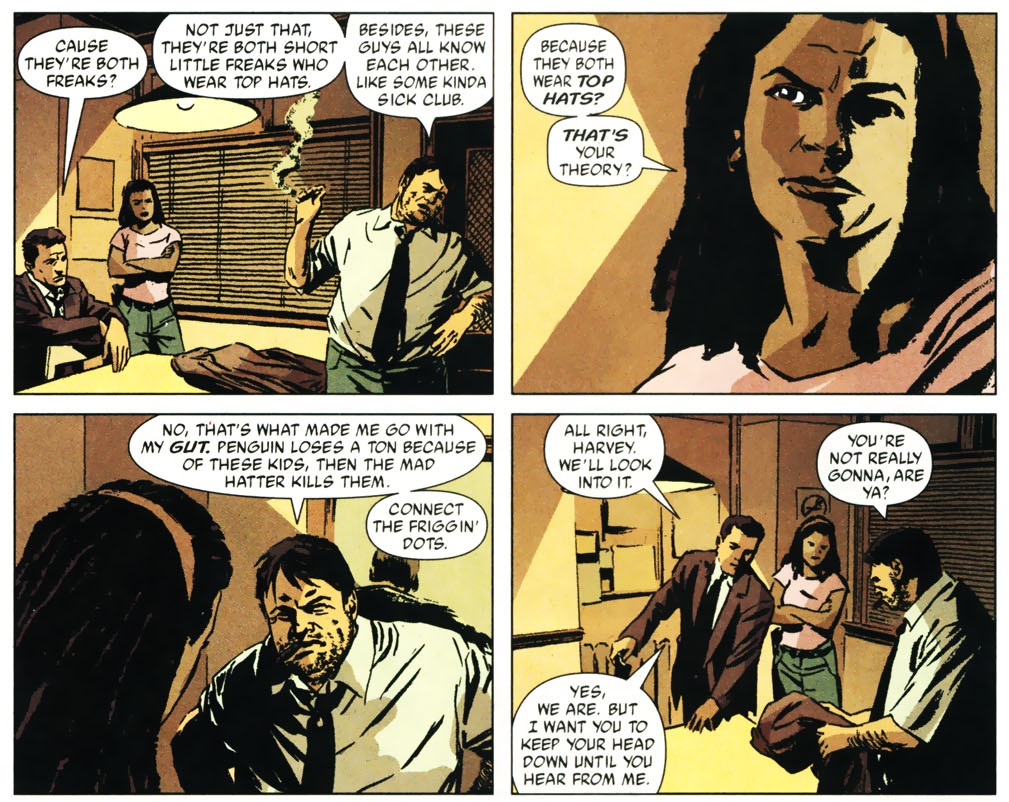

Yet Ed Brubaker provided something even better: a perfectly devastating ending to Bullock’s character arc. Decades of fiction have programmed us to trust a cop’s gut instinct, but – true to Gotham Central’s gritty revisionist tone – ‘Unresolved’ proves Bullock wrong… It turns out he really is just a flawed, decrepit, old-school crooked cop whose judgment isn’t always on the money.

Rather than glorifying the trope of the tough policeman who places personal prejudices above the rule of law, the comic has Bullock pull off vigilante justice against the wrong guy (the Penguin) and in the end things get pretty dark:

Gotham Central #22

‘Unresolved’ should’ve been one hell of a send-off for Harvey Bullock. But, you know, comics…

Sure enough, it took only a couple of years for the franchise to revert into a mostly familiar status quo. In 2006’s ‘One Year Later’ soft reboot, we find out that – unsatisfyingly off-page – sometime in the previous months ‘Gordon sensed corruption in Gotham at the highest level’ and sent Bullock to investigate, uncovering and exposing so much dirt that, as a repayment, he was allowed back in the force, on the condition that he wouldn’t make a single mistake. I suppose that could be a cool story to tell, but DC never got around to it, so all we were left with was a sense of regression.

The new Bullock wasn’t uninteresting: he was a weary, tragic figure making up for his mistakes and trying to keep straight, despite his cynicism. Nevertheless, his characterization was fairly inconsistent because the thing that had defined Bullock for so long and gotten him thrown out of the police force was that he cut corners because he wanted justice (he was the dark version of Batman and envied him), whereas now he was treated as simply having been bent himself:

Batman #652

The whole thing felt off for me, so in my headcanon Harvey Bullock became a different version of the character, perhaps having migrated from some alternate timeline (like the Batman: Earth One series) in one of the DCU’s many multiversal events. For me, post-Crisis Bullock was last seen in Gotham Central #22, pissed that he never got as much respect as that guy in a costume with pointy ears.

2025’s second weekly reminder that comic book page layouts can be awesome:

Dogs of War

Ian Fleming’s James Bond #6

Que presente impresentable

The fact that the second volume of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters finally came out should’ve made the pick for Gotham Calling’s 2024 Book of the Year a clincher. Emil Ferris’ long-and-eagerly-awaited continuation of her dense, brilliant debut opus keeps up the impressive standard of dazzling visuals, sprawling narrative, and thematic breadth set by the first installment.

Once again, Emil Ferris resorts to the device of stream-of-consciousness ballpen drawings on a notebook paper of a grade-school fan of old horror movies and comics to compellingly engage – in quirky, brutal, and haunting ways – with topics ranging from classic art to gender norms, from the Nazi Holocaust to life among the underclasses of 1968 Chicago. There is an oddly timeless feel to the book, although I suppose it also taps into the current cultural moment, as some the most enthralling works of last year likewise used nostalgia-tinted horror imagery to translate existential anxieties with touching creativity (from David Small’s Eisneresque anthology The Werewolf at Dusk and other stories to Jane Schoenbrun’s beautifully eerie film I Saw the TV Glow). And while the shock of the previous volume’s inventiveness and originality isn’t there anymore, Ferris’ assured experimental storytelling and commitment to turn *every* *single* *page* into a mini-masterpiece make this a highly rewarding and affective read, as we get to delve deeper into the protagonist’s fucked up family life and into the investigation of her neighbor’s mysterious death. The two books of My Favorite Thing Is Monsters are instantly recognizable as fundamental contributions to the medium that I will no doubt revisit over time.

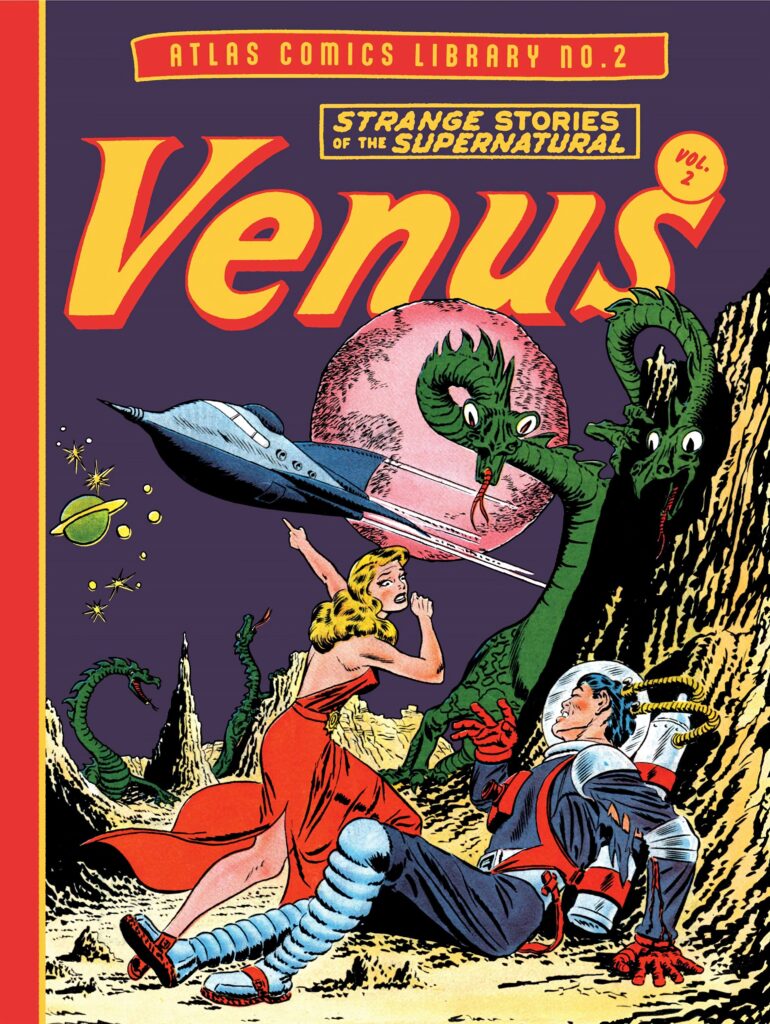

Still, if I’m to be honest, the most fascinating read of 2024 was actually a reprint…

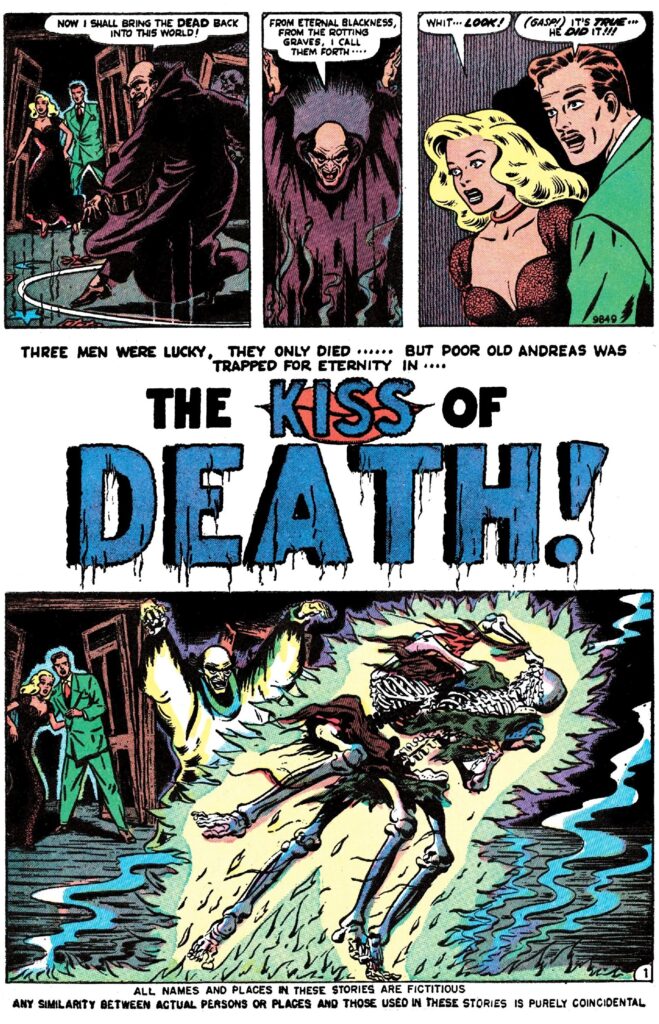

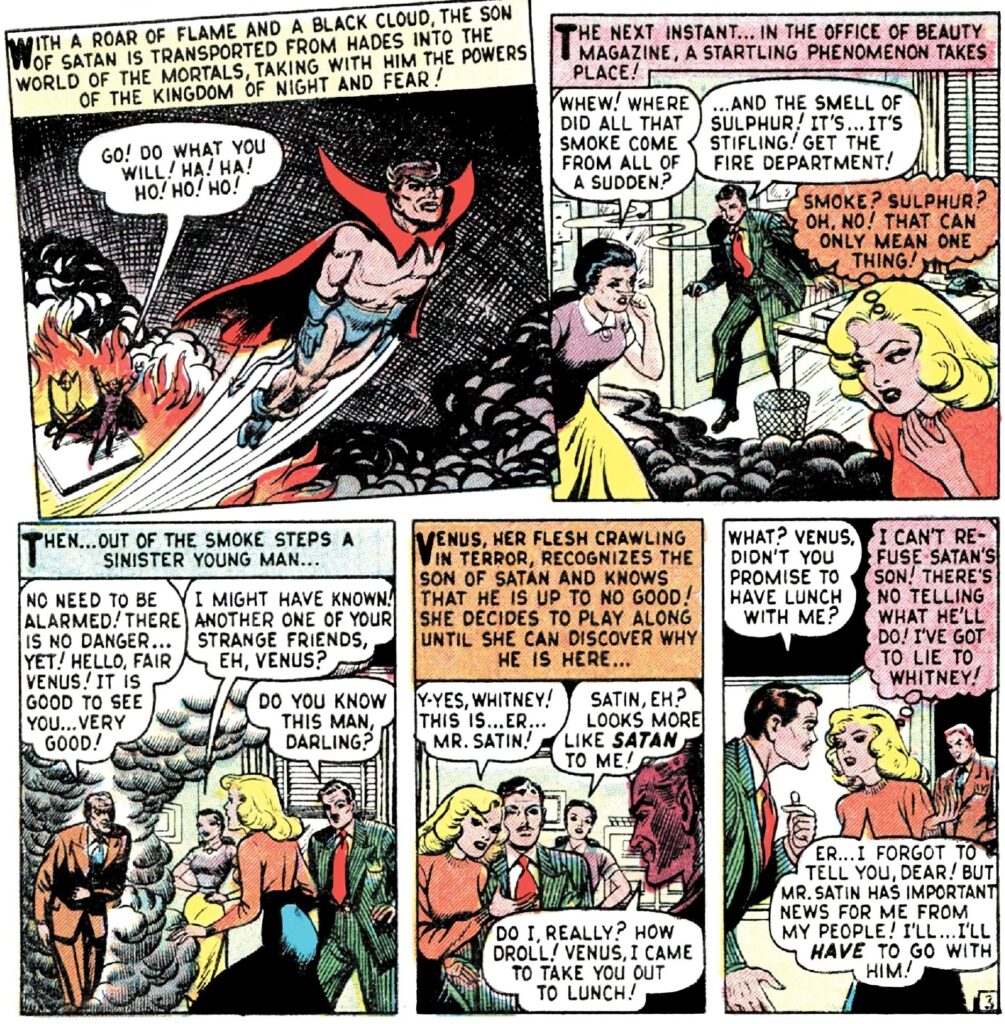

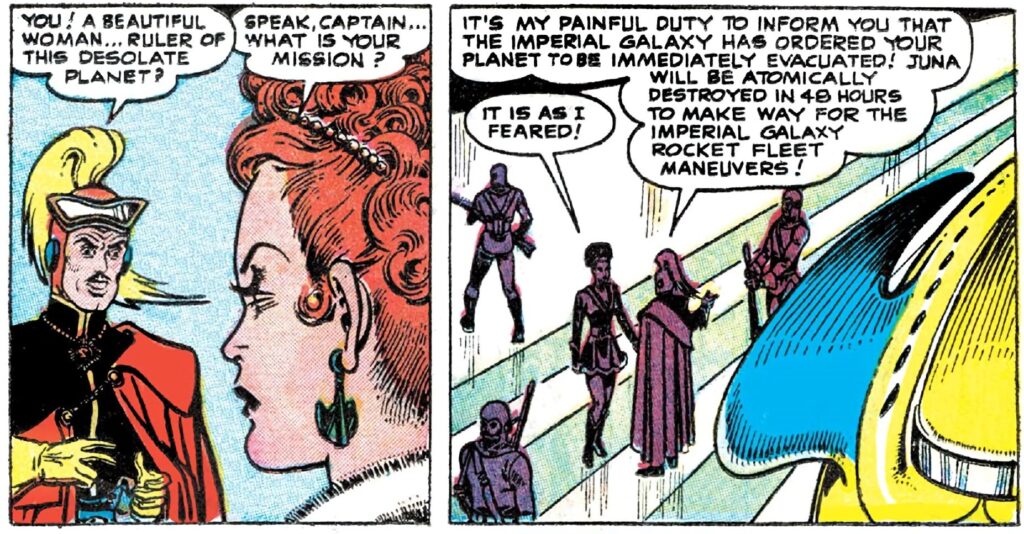

Back in 1948, (pre-Marvel) Timely Comics were throwing all kinds of shit at the wall to see what stuck, so somebody came up with the idea of doing a romcom series about Venus, the Goddess of Love, coming to Earth (initially from the planet Venus?!) and working for a beauty magazine, where she fell in love with her boss, Whitney Hammond. Things only got more bonkers from there, as, for the next few years, a host of writers and artists shifted the comic from genre to genre, turning it into an incredible time capsule of evolving trends during that wild postwar interlude when superheroes’ popularity had lost the initial momentum and publishers were eagerly searching for the medium’s next big thing.

The series’ first nine issues had been collected in a volume over a decade ago, as part of Marvel’s Timely and Atlas Masterworks line, but for some reason those folks never got around to republishing the rest of the run, which was a shame because that’s where things got really strange and experimental. Fortunately, in the meantime, Fantagraphics has struck some kind of deal with Marvel, so I finally got to feast my eyes on this Golden Age gem in the form of a stunning-looking hardcover, edited by Michael J. Vassallo.

I never knew quite what to expect next while going through this book. Every time I thought I got it pegged, to some degree, it threw me off with an oddball story decision or a shockingly vicious line… If one tale is about a jealous secretary trying to trick Venus in order to try to get her job and marry Hammond, in the next one Venus is interviewing a scientist and so she gets on a rocket and flies to the moon (in 1950), where there is a volcano eruption and she has to bargain with Jupiter for help.

The stakes keep varying wildly, occasionally reaching the levels of a Superman comic, even if Venus’ solutions don’t usually rely on superhuman strength, but rather on her ability to manipulate people into falling in love. There isn’t exactly a formula, although the early stories do feature recurrent elements: Della the secretary scheming to discredit Venus in Hammond’s eyes, men doing stupid things (including destroying the world) because they get horny for our drop-dead gorgeous heroine, and Venus using her connections to the Roman pantheon (and sometimes the Norse pantheon, because why not) to get out of trouble.

And as if this wasn’t enough to make for a fun reading experience, the volume features lovely art by Werner Roth and, among others, a young Gene Colan. In fact, there’s an amazing roster of talented artists whose craft and professionalism elevate the material above mere campy shenanigans and into something that feels like an engagingly unique combination of enmeshed creative and commercial forces.

(Sounds like a kooky sitcom, right? Well, there’s mass murder in the next few pages…)

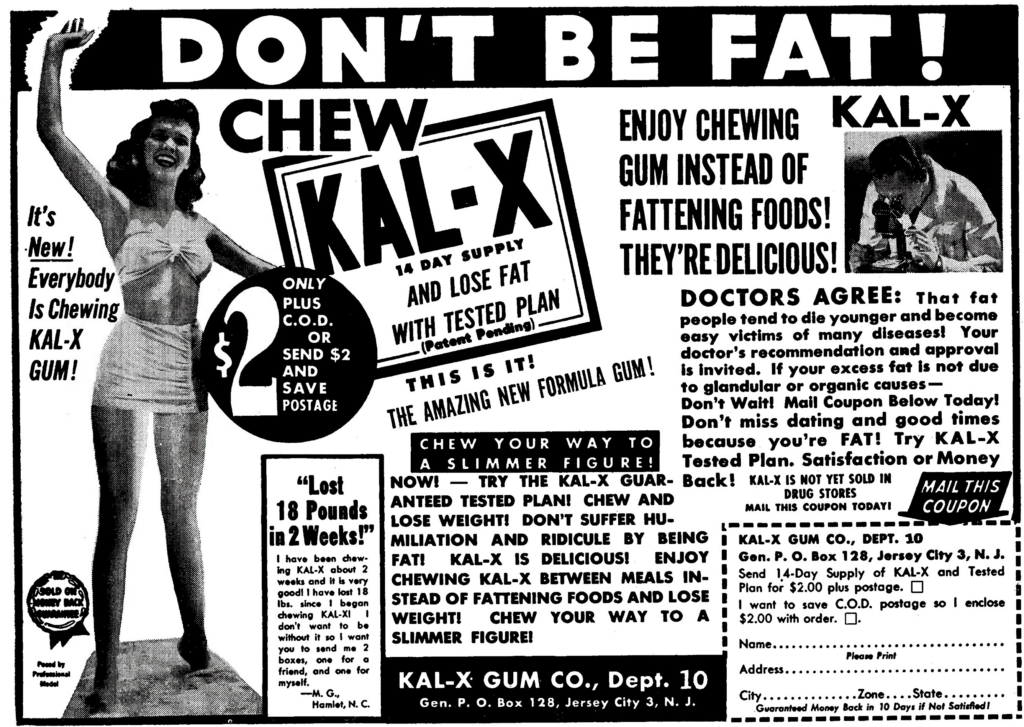

Atlas Comics Library no.2: Strange Stories of the Supernatural – Venus, vol.2 is clearly a labor of love and a treat for comic book fans, with thick paper, carefully restored colors, and wide enough margins for each page to be easily and fully visible in all its glory (as opposed to the annoying tendency in comics collections to fill the whole surface, thus obscuring some of the art or dialogue near the binding, where pages converge). If you’re reading this blog, you probably know I love old-timey covers, so it will come as no surprise how much of a kick I got from staring at these massive pages, with their neat mise-en-scène and taglines like ‘There was only one way to learn the horrible secret of the TOWER OF DEATH! You had to die, first!’

Plus, not only do we get a typically informative introduction by Vassallo, but also a reproduction of the original issues in their entirety, complete with the adverts. I’m sucker for this sort of stuff – the ads seem even more time-bound, telegraphing the era’s understanding of what was considered appealing for teenage girls, although not always in a linear way… Some of their values and assumptions aren’t so different from the ones in today’s publicity, but the thing is that they’re way more shameless and irony-free.

(And just wait until you see the ad for bras, a few issues later…)

Venus also contained unrelated filler material in the middle of each issue. Some of this were prose pieces of various genres, ranging from down-to-earth love stories (in ‘A Chance For Happiness,’ what I assume is a male writer has written a tale from the perspective of a woman in love with a male writer) all the way to supernatural thrillers (‘The Isle of No Return’ has got to be a Lovecraftian tribute/pastiche, hence its closing line), including a couple of paranoid tales typical of the zeitgeist (‘The Madmen of Mogan’ and the H.G. Wells’ rip-off ‘Death to the Hairy Monsters!’).

Other short stories are comics that share nothing with the Venus strip other than some superficial aesthetics, contributing to the general sense that editors were willing to keep trying out different stuff all the time. For instance, ‘The Madman’s Music’ is a chilling, quasi-poetic gothic yarn by Pete Morisi and ‘The Last Rocket!’ is a space opera that crams a mix of Star Wars and The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy into just three pages… The latter is as frantic as it sounds, although Joe Maneely hilariously draws it in the most deadpan style:

To be fair, at least ‘The Last Rocket!’ has a weirdness-meets-romance-with-a-straight-face vibe that doesn’t feel entirely out of place. In fact, the series did take a hard turn to science fiction in the next issue. Tapping right into my passion for 1950s’ sci-fi, we get a tight little spy yarn within a robot rebellion, followed by a trippy adventure in which Venus is reduced to the size of an atom and becomes a prisoner in a scientist’ brain.

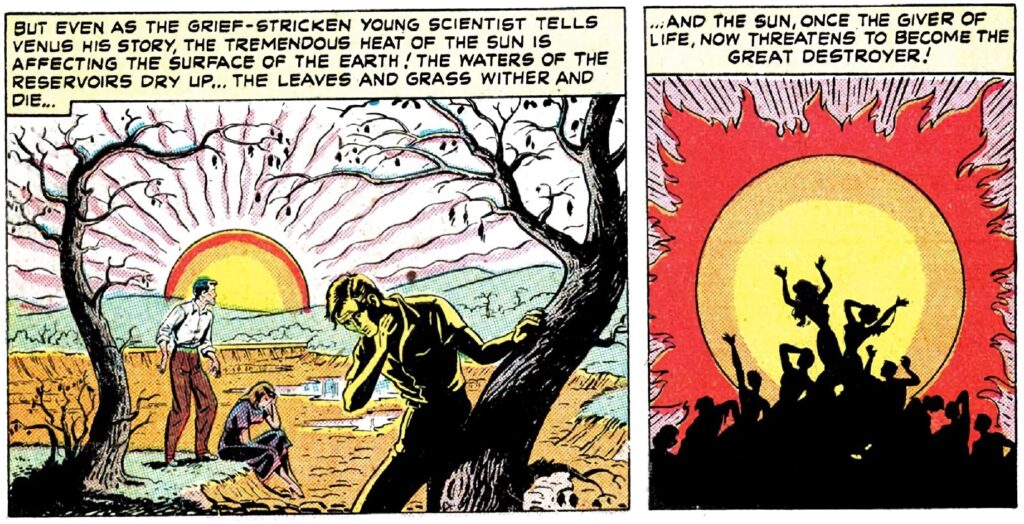

Hell, even before that, the issue opens with the end of the freaking world, showing us that the Earth has veered off its axis and is heading towards the sun, thus anticipating both The Twilight Zone’s ‘The Midnight Sun’ and The Day the Earth Caught Fire, including this terrifying atomic echo:

Now, the artwork notwithstanding, I’m not saying these comics hold up to being judged by conventional standards. Their plots are nonsensical (with incoherent behaviors, unclear motivations, baffling developments, loose ends) and, obviously, there is often an undercurrent of sexism at play in the way women are treated and depicted (as well as occasional racism, like in the ecumenical orientalist fantasy ‘Trapped in the Land of Terror’). However, if you’re willing to appreciate the comics as pop art surrealism, with a freewheeling, dreamlike flow of wacky ideas and memorable imagery, then Venus is an absolute hoot.

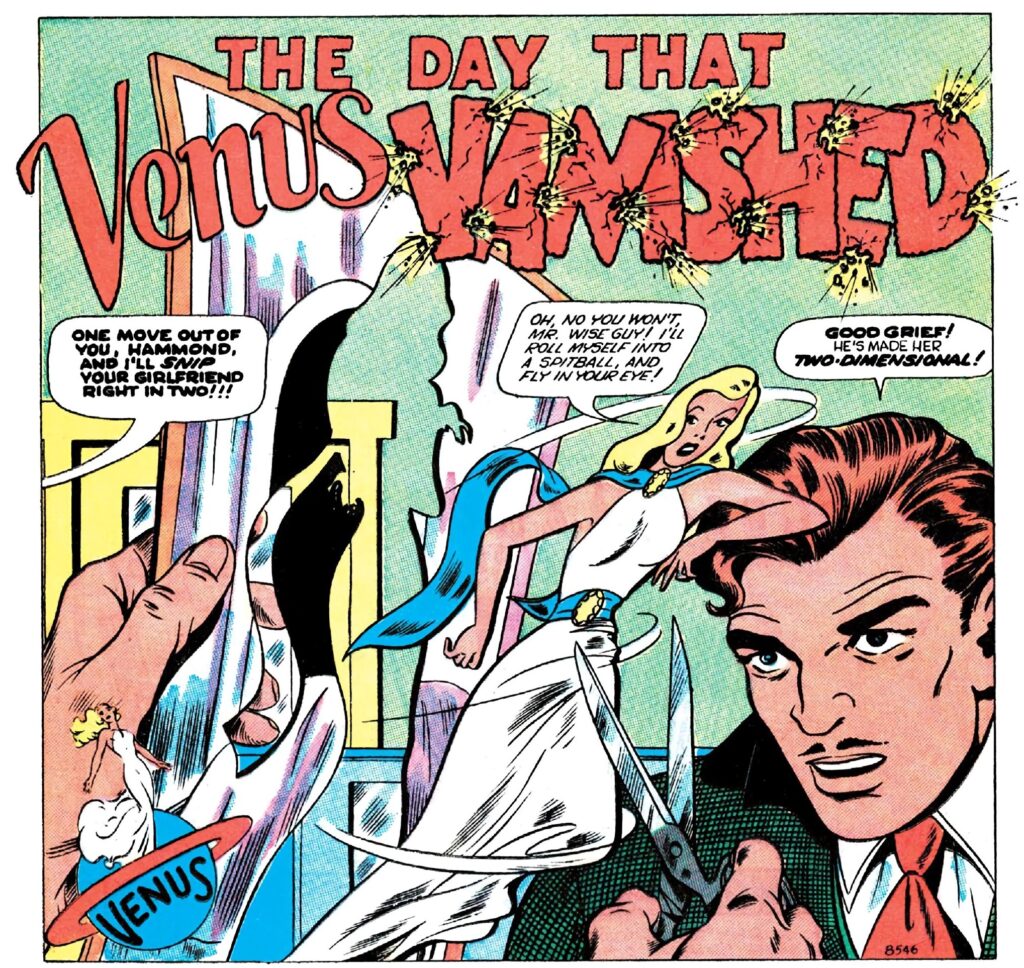

That said, it’s with issue #15 that the book takes a leap from cool to awesome. Bill Everett, who by then had assumed the writing, drawing, and lettering of all the Venus main features, turned the series into a pre-Lynchian horror book. If, at the time, EC was putting out tautly constructed short horror stories (which Fantagraphics has also been collecting in great books like Fall Guy for Murder and The High Cost of Dying), Everett delved into the sheer disturbing eeriness of unexplained setups, uncertain payoffs, and open-ended mysteries… The average tale would finish with Venus as befuddled and as creeped out as the readers, still unsure why dolls were bleeding in the previous panel and honestly concluding that ‘we’ll never know.’

Also, the lettering was much more creative:

Marvel fans will probably know Bill Everett as the creator of Namor the Sub-Mariner (to which he returned decades later, even penning a crossover that brought back Venus from obscurity, in 1973) or, more likely, as the co-creator of Daredevil. His stint on Venus, though, is the kind of run you get in comics every so often when someone comes along and memorably redefines a property through their bold personal vision.

Everett was not afraid to mess with whatever loose formula had been in place. In fact, through his inconsistent characterization, I’d argue he made the series much more progressive in terms of gender politics. Della stopped being defined as a jealous secretary and Venus herself, instead of asking gods for help all the time, became more active and even got some zingers (‘Death is cold, sir… but I assure you I’m very warm now!’).

Rather than fawning over Whitney Hammond, Venus assumed the primary role of paranormal investigator, halfway between John Constantine and Hildy Johnson, from His Girl Friday. She was now a committed reporter who defiantly chased after each hard-hitting story (for a beauty magazine) and no longer took shit from the condescending men around her.

Horror and romance can actually work quite well together. In comics alone, there are plenty of magnificent examples, whether it’s obscure short stories like The Vault of Horror’s ‘Reunion’ or avowed classics like Swamp Thing’s ‘Rite of Spring.’

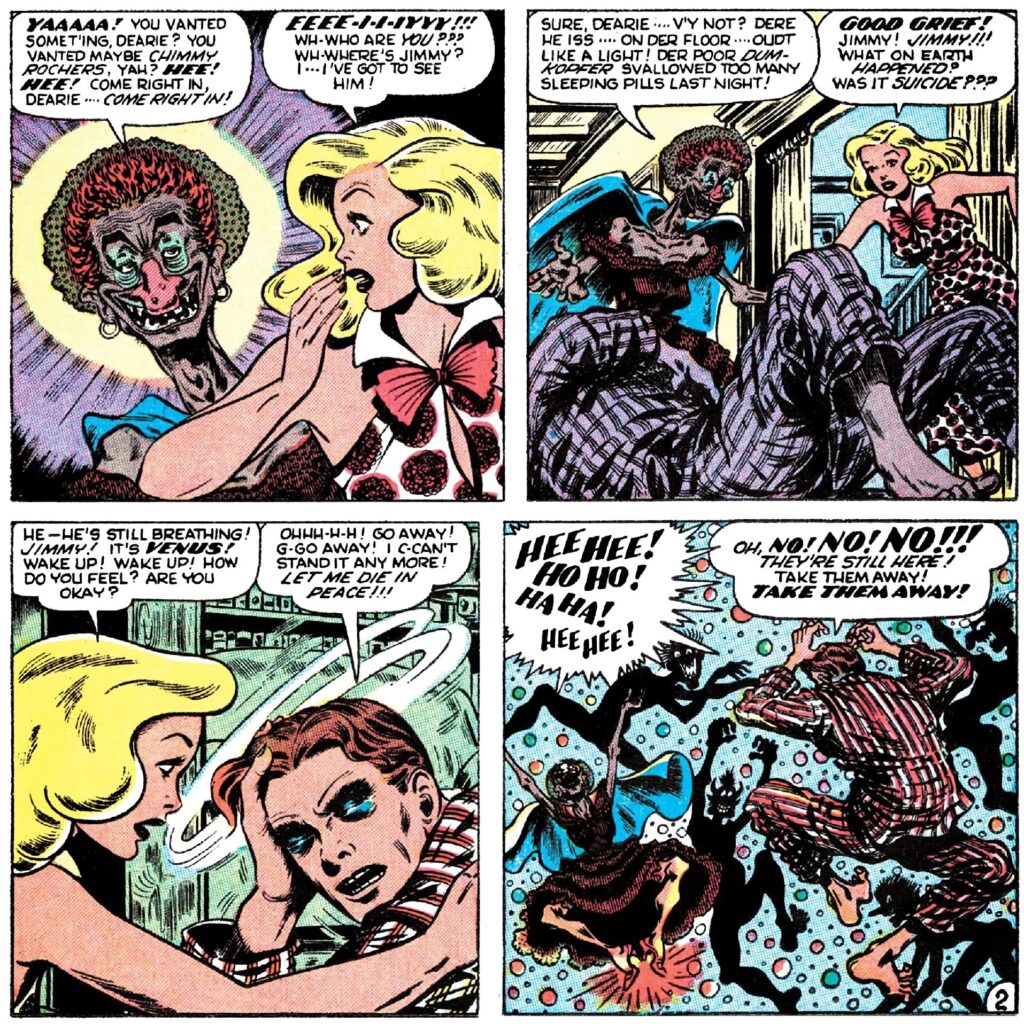

However, Bill Everett soon straight-up dropped Venus’ romance angle, except for a jarring bit in the Cold War monster epic ‘The Stone Man!’ (and, I suppose, the unforgettable final panels of the mind-boggling ‘The Kiss of Death!’). For the most part, Everett just dived into full-fledged horror, filling the issues with atmospheric artwork, macabre grotesqueries, and an increasingly dark tone. Perhaps he needed to get it out of his system, as expressed in the metafictional – and possibly autobiographical – tale ‘Cartoonist’s Calamity!,’ about a comic book author who is literally haunted by the freaky creatures he draws:

(I would be amiss if I didn’t point out Venus is wearing a pretty sweet outfit.)

Venus would go on to be retconned into the main Marvel Universe, most notably through Jeff Parker’s and Leonard Kirk’s enjoyable Agents of Atlas, in 2006, but these pages suggest a whole different type of alternate history. If pre-Code Hollywood was batshit insane, the same can be said for many of the books made right before the comics industry accepted the CCA’s censorship, in 1954. For a few years, publishers were no longer targeting just kids, yet they weren’t sure what exactly they were doing instead, so they let creators experiment with all kinds of crazy shit. And this volume is a wonderfully entertaining reminder of how comics could’ve soon evolved in offbeat and much more imaginative ways if only they had been let loose for longer…

Hell, these read like just the sort of comics that would appeal to Karen Reyes, the protagonist of My Favorite Thing is Monsters!