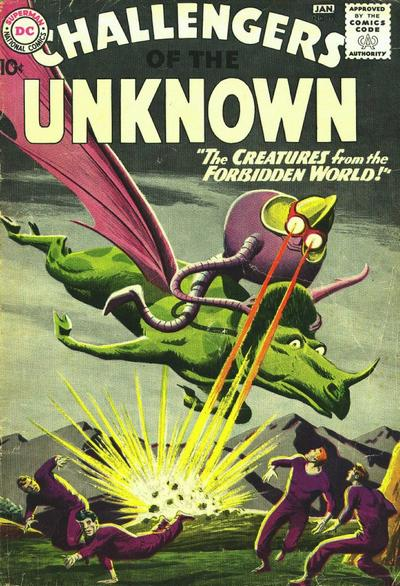

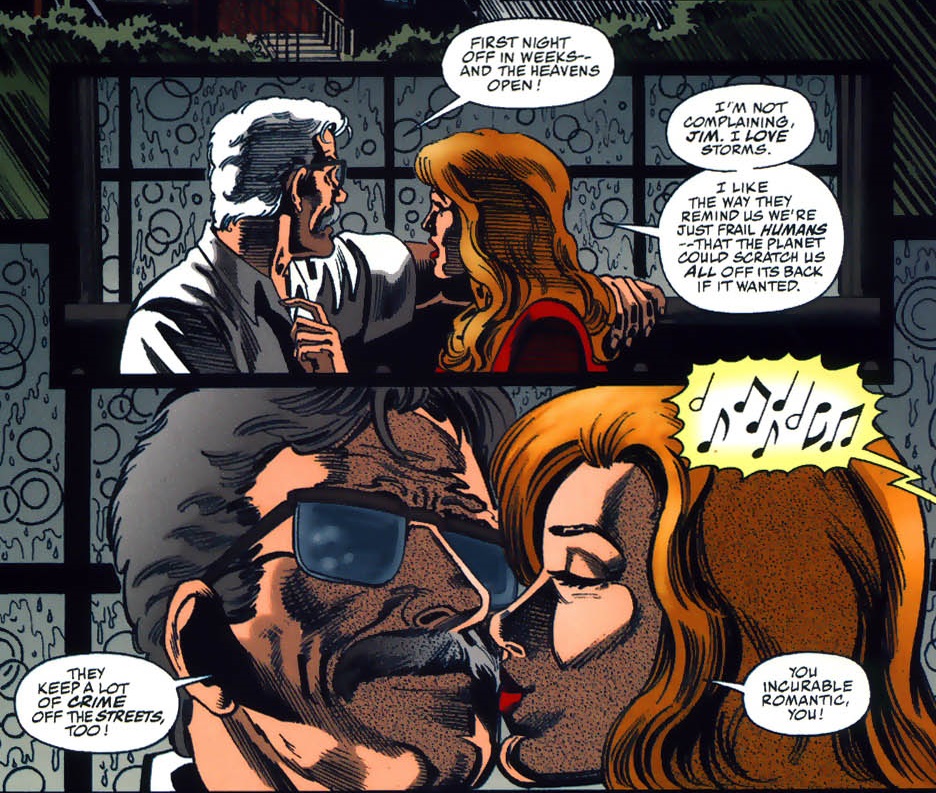

When it comes to superhero comics – and Batman stories in particular – there tends to be a division among fans between those who privilege more lighthearted fantasy and those who favor grim-and-gritty aesthetics or narratives with literary affectations. I keep ping-ponging between the two camps depending on my mood… It’s not just that I can get a major kick out of both Scott McCloud’s upbeat Superman Adventures and Mike Grell’s revisionist Green Arrow; it’s that I can find self-important proto-realism just as annoying and uninspired as all the silly, derivative dreck that has been a part of the genre from the start.

Then, of course, there are those books that manage to work on both levels. Some of the most deconstructive, sophisticated peaks of this art form double as kickass thrillers packed with fist-pumping ‘fuck yeah’ moments (most famously Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns, but also their descendants, like Alias and Jupiter’s Legacy). At the other end of the scale, among the most escapist, unabashed pulp you can occasionally find all sorts of stimulating subtext and imagery.

For an example of the latter, let us take a close look at ‘Execution on Krypton!’ (World’s Finest Comics #191, cover-dated February 1970).

The script, written by Cary Bates and edited by Mort Weisinger – one of the main architects of Silver Age DC – operates on that era’s core principle of constantly prickling readers’ curiosity. While the cover (rendered by Curt Swan in his classic, elegant style) suggests that the Caped Crusader and the Man of Steel will travel back in time to the planet Krypton before it exploded, where Superman’s father will condemn them to death, the opening splash offers an alternative teaser, as a flashforward shows Supes’ parents – Jor-El and Lara – running a crime school (i.e. teaching students to commit crimes) in front of our baffled heroes. Thus, readers are presented with a couple of counterintuitive premises before being launched into the proper story…

Not that the story itself wastes any time before setting up new intriguing elements. All you have to do is turn the page and you’ll see Lara and Jor-El (who died on Krypton years ago) briefly materialize in present-day Earth, coincidentally near Batman and Superman, who overhear them plotting a crime. The Kryptonians’ apparent criminal activity, mind you, shocks the heroes – and, according to the omniscient narration, should presumably shock readers – way more than the fact that these two dead aliens from Superman’s past suddenly pop up out of nowhere, because in the first decades of the Comics Code Authority characters – and consumers – were more used to dealing with magic than with moral ambiguity!

These aren’t the most interesting mysteries though, as we will get pretty direct explanations for them later on. In turn, my curiosity is much more engaged by all the questions the comic raises (often implicitly) but doesn’t bother to answer, letting our imagination run wild instead. Just take the first panel in the page above, where Superman – along with his Bat-buddy – nonchalantly flies to another galaxy while simultaneously travelling to the past by using his super-speed to break ‘the time-barrier.’ This was such a common occurrence in the life of pre-Crisis Earth-1 Superman that none of them treats this as remarkable in itself, much less reflect upon all the science fiction paradoxes that come with such carefree trips back and forth across the 4th dimension… Hell, there isn’t even the smallest qualm about the possible effects of changing history, as immediately after arriving the World’s Finest duo set out to squash a student demonstration (or perhaps they’re just so damn pro-establishment they’re willing to risk disrupting the whole space-time continuum in the name of order… decades ago… in a distant planet!).

Indeed, I hardly had time to wrap my head around the whole spacetime trip when my mind was thrown into a whole new tangent by the student protest thing. On the one hand, the old version of Krypton had traditionally been depicted as a surrealist technological utopia full of strange sci-fi concepts (check out all the futuristic architecture!), so it isn’t too startling that they have robot teachers. On the other hand, the veteran art team of penciller Ross Andru and inker Mike Esposito draw human figures that look not only relatively naturalistic, but also modelled on the clothing fashions and haircuts of the youth in late sixties’ USA, creating an obvious parallel with the then-current student movement. So, besides puzzling over how robotized higher education works and what the protesters are specifically rebelling against (is it the dehumanization of teacher-student relations? robots’ strict pedagogical methods? or perhaps the way mechanization is destroying the prospect of future uni jobs?), a part of me also wonders what compelled 21-year-old Cary Bates to write a comic that seems more sympathetic toward the robot teachers than toward the human students…

The angle of the panel above (a reverse-shot from the last panel in the previous scan) could suggest a cold, creepy distance in the way the staff literally looks down on the students (arguably validating the latter’s resentment) and Jor-El’s thought balloon is ambiguous (is he worried about the teachers or the protesters?), but the rest of the sequence leaves no doubt about the overall moral economy. Rather than talking to the demonstrators about their concerns or even trying to mediate a solution, Superman and Batman immediately identify them as a threatening mob and proceed to physically undermine the protest – in a move later ripped off by Judge Dredd comics, they weaponize a weather control tower, using a shower of silver rain as the equivalent of a police water cannon (yes, silver rain… Bates doesn’t miss the opportunity for further whimsical touches, identifying other artificial weathers as glow snow, sleet pellets, and scented wind). Ideologically, this feels reactionary as hell, but it is completely in-character with the personality of the two heroes, who at the time were aggressive defenders of law-and-order and proud protectors of the status quo.

The politics aren’t the only thought-provoking bit of characterization going on here. Because of Krypton’s red sun, Superman loses his powers and has to act more like a strategic-minded athlete. Meanwhile, because of the the heavier gravity, Batman brought anti-gravity boots and manages to float in the air (in order to distract the students, who sound like a bunch of stoners), so it’s as if the two superheroes have switched roles. What I most like about this is how smoothly they adapt to the change, quickly coming up with a plan based on their new abilities, thus displaying the resilience and resourcefulness of characters who have gotten used to transforming or swapping bodies on a monthly basis – and, crucially, who are used to working together in odd circumstances (this was before the mainstream decided these two longstanding friends worked better as natural enemies).

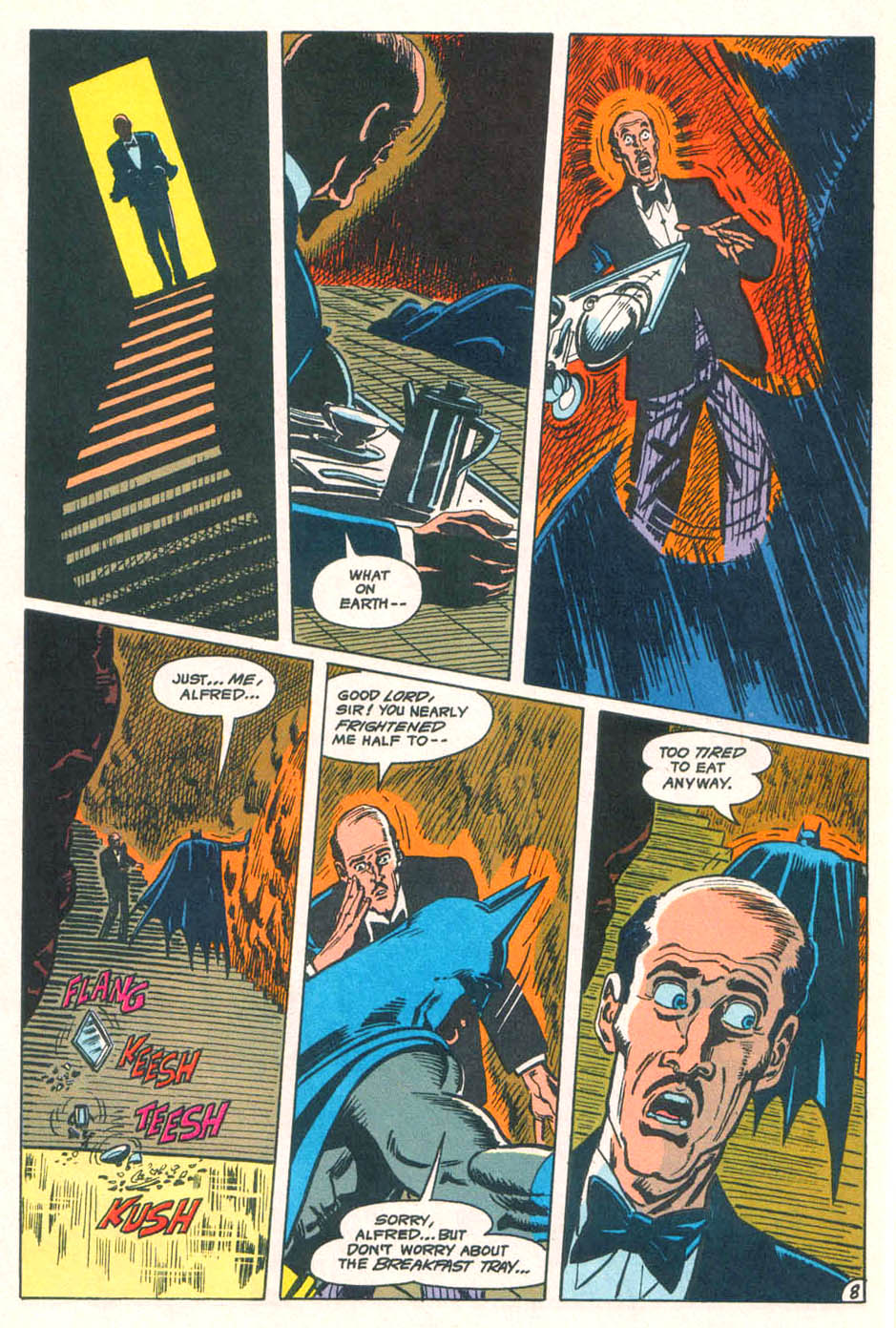

More than any individual idea, however, it’s the sheer barrage of throwaway ideas that makes World’s Finest Comics #191 such an enjoyable read. For instance, in the page below every single panel contains at least one concept that would fill most of an issue in today’s age of writing-for-the-trade and decompression, starting with Superman’s hilariously convoluted explanation for their attire (come to think of it, why is Batman wearing his suit anyway? I guess it gives him confidence no matter where he is…).

I love everything about this sequence, from Batman’s utterly unphased acceptance of Jor-El’s invisibility ray down to Superman’s inner monologues finally acknowledging that there is something a bit weird about meeting your dead parents before you were born! Out of all these dreamlike moments, only the one about the cinema actually pays off down the line – the rest just seem to be there for our instant delight and wonder.

Such a relentless pace of blink-and-you-missed-it ideas that aren’t there to be developed or explored but rather to create a sense of overwhelming otherness is the kind of stuff Grant Morrison and Warren Ellis would later build their careers on. And, of course, Andru and Esposito – plus whoever did the groovy colors – help nail each beat with their fantastic designs…

Following a slice of social commentary (surprisingly liberal, at least compared to the previous scene’s hippie-bashing), the sequence culminates in a meal at Jor-El’s and Lara’s place, where the transparent chairs and the triangular table hover in the air:

(A couple of panels later, we get to see the floating chairs from below as they all relax in the garden, foreshadowing the tale’s final image. It’s one of many beautiful panels that combine mundane postures with out-of-this-world visuals without making much of a fuss about it.)

After this very short breather, the adventure plot leaps with forward momentum on a panel-by-panel basis. Batman and Superman secretly follow the Kryptonian couple through the planet’s fire jungle, only to be caught in an underground school – because the cave’s walls are equipped with ‘echo-magnifiers’ that give them away – where Jor-El sentences them to an execution via a ‘death-cube,’ as seen on the issue’s cover. We thus get a fun deathtrap escape scene (a staple of Batman and Superman comics) but the whole thing turns out to be a test (a typical Silver Age fake-out) leading to the World’s Finest team enrolling in the crime school, where they soon manage to get the highest scores… After all, not only are they are seasoned crimefighters (Batman even has a degree in criminology), but they’re both geniuses who had studied Kryptonian tech in their spare time. (A montage serves to give us more glimpses of this incredible world, including offbeat versions of safecracking and counterfeiting. The students’ final scores are tabulated on ‘electronic data-blocs.’)

This is where the story takes a pretty unexpected turn, as the reason Superman’s parents had been teaching crime is finally revealed. The petrified body of a godlike alien explorer named Calox has been found in the Kryptonian island of Bokos, but the locals chose to merely keep it in a museum, so Jor-El is planning to steal it in the name of science (he’s convinced he can bring Calox back to life and thus obtain from him the ultimate secrets of the universe!). So, you may ask, was the crime school specifically set up in order to train people to commit this daring heist? The answer is yes, but it’s also much more elaborate than that, because Krypton is still full of surprises:

Once again, faced with this ludicrous island where dishonesty is not only legal but *mandatory*, I cannot prevent my thoughts from flying all over the place, imagining how such a society came to exist and how it can possibly operate.

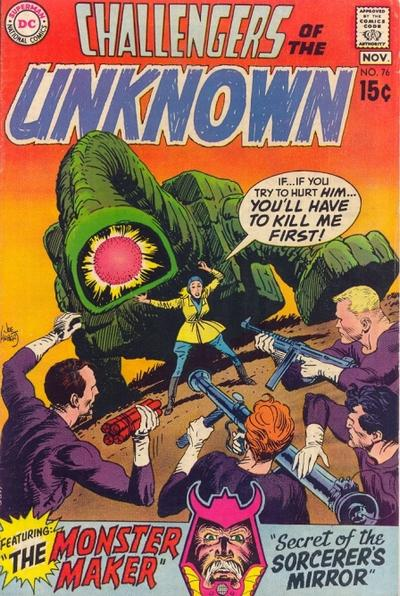

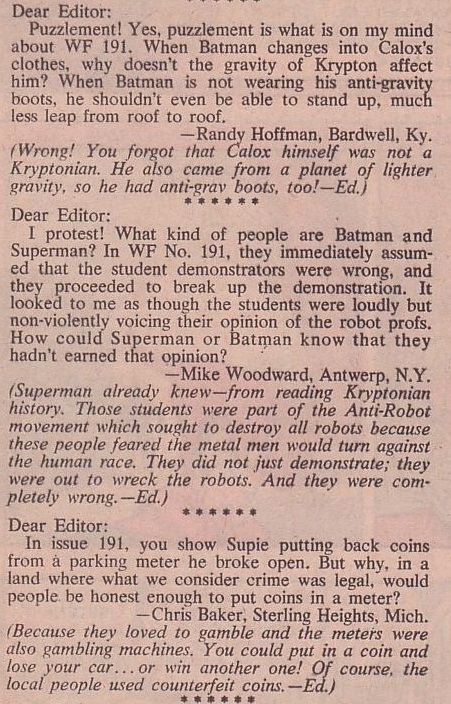

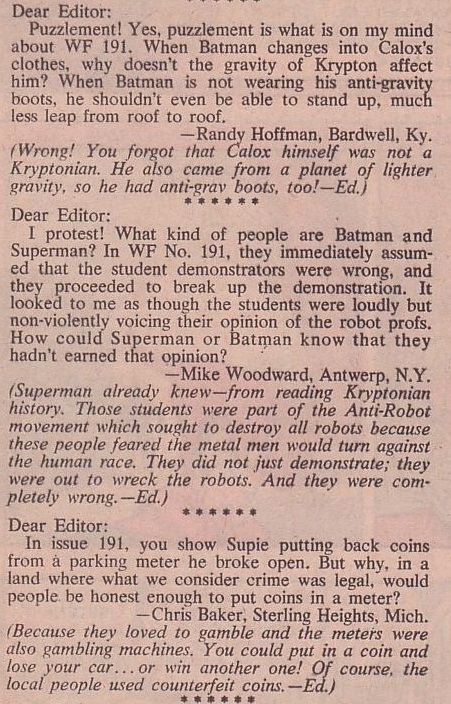

Having established the rules in the three panels above, however, ‘Execution on Krypton!’ proceeds without blinking. The story has fun with the notion of its wholesome heroes being forced to commit thefts in order to blend in and then has them pull off a wacky caper involving the type of switcheroo that was par for the course in World’s Finest Comics. And if you have any lingering questions, you can settle them with the editor, in the letter pages of future issues:

World’s Finest Comics #194

World’s Finest Comics #194

There are plenty of snarky websites out there making fun of old – and new – comics and movies, pointing out plot holes and implausibilities, but fans know the real fun is trying to find a hidden logic and to speculate about the ramifications of what is there on the page. Rather than challenging the work or acting superior to it, such thought experiments are part of a game between readers, creators, and editors that continues after the story is over, as you can see from Weisinger’s answers in this letter column.

But the story isn’t over yet! Just when you think Batman and Superman have achieved their goal, Cary Bates introduces further drama and complications in the penultimate page:

(There is clearly a lot going on in Superman’s head, as his thoughts on the left panel confirm that he decided to travel across time and outer space on little more than a whim, without fully thinking through the implications…)

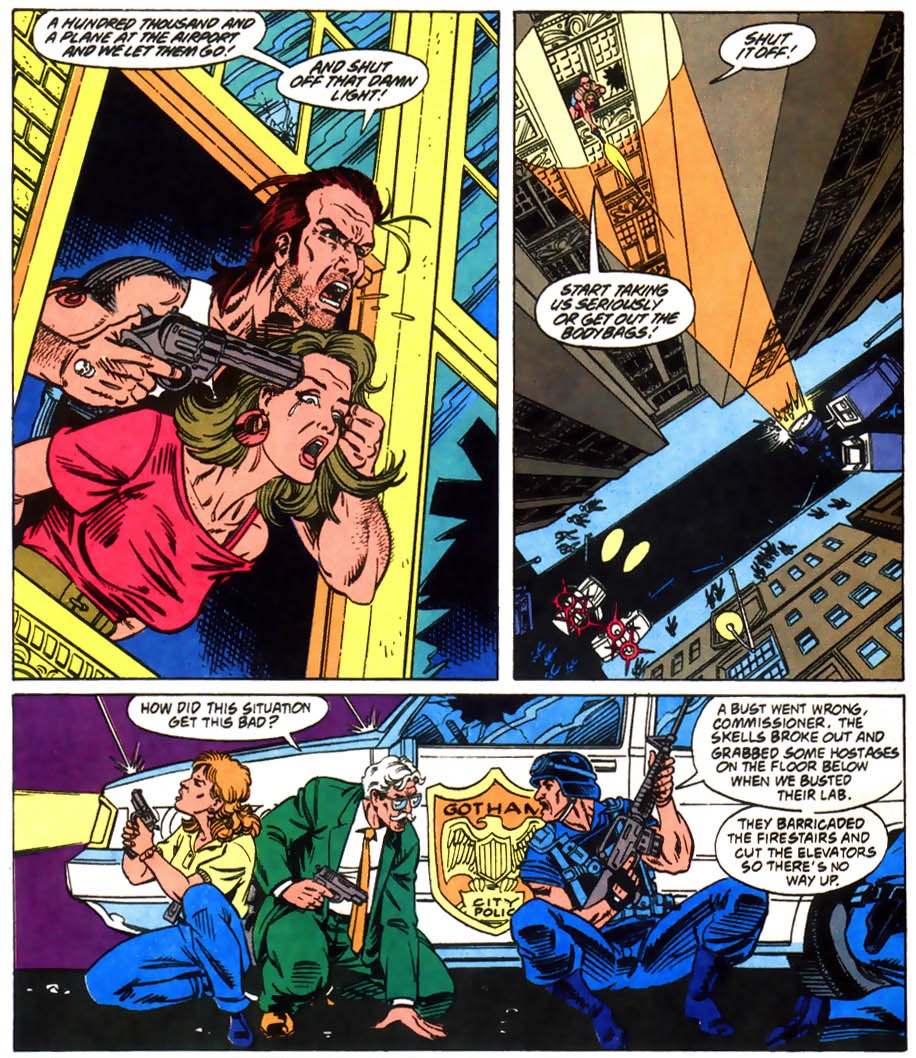

A deus ex machina sort of saves the day, as the Caped Crusader and the Man of Steel are conveniently teletransported to back to Earth, in 1970, through an experimental time-vortex that the army just happened to be developing. The odds behind such a turn of events are, of course, preposterous, but in Bates’ defense he doesn’t let his protagonists off that easily… The vortex will automatically transport them back to Krypton – or, rather, it would have done, if not for the timely intervention of General Hill, who quickly realizes Earth can’t afford to lose these two heroes and, therefore, takes drastic measures in his own hands:

This final twist is the perfect capstone to an epic yarn that kept surprising me at every turn. General Hill, a character that had never showed up in the comics before (even in this comic, we had only seen him in a coma), turns out to be the main hero, sacrificing years of research – and, as one hysterical scientist points out, a 22-million-dollar investment – to save Supes and Bats!

If you try really hard, you can squeeze two thematic readings out of this dénouement. According to the most generous one, while the World’s Finest duo’s top motivations throughout the tale are spying on Superman’s dead parents and stealing a god, in a roundabout way they do end up achieving something positive by causing a serious blow to the US military-industrial complex at the height of the Vietnam War. Alternatively, you can read ‘Execution on Krypton!’ as a frank acknowledgement of the military’s own priorities: sure, R&D is important, but the main thing is securing a force that can effectively contain student protesters.