This is Gotham Calling’s 500th post!

I like to mark these round numbers with humorous tours of Batman’s quirkiest villains but, since I’ve already done one of those earlier this year, this time around I’ll go for something more original and nail down the top 50 movies of a genre that doesn’t always get enough love in this blog: westerns.

It’s surprising how little westerns show up in Gotham Calling, given that they’re one of my default sources of entertainment whenever I need undemanding comfort food for the brain… Between films and comics, I must’ve digested hundreds of tales of this – admittedly limited and repetitive – branch of storytelling. And I’m still not tired of it!

What is a western? For the purposes of the list below, it can be any movie set in the Old West (i.e. in 19th-century North America) as long as it includes some of the main tropes associated with the genre: horses, gunfights, outlaws, comradery, frontier life, and the violent construction of ‘modern civilization’ (from genocide to resistance against emerging values and institutions). It’s a tautological definition, I know, but I’m not going to pretend I invented this genre – I came to it after it had been fully-formed for almost a century, so I’m more interested in recognizing patterns than in enforcing a strict conceptualization.

There are recurrent themes, such as toxic masculinity (usually embodied by John Wayne or Lee Marvin) and competing understandings of justice. On a surface level, though, these are stories about the United States of America as a colonial nation built by firearms, alcohol, and fucked up racial politics. Plus, since circulation across borders has been a key part of American history as well, the list includes a bunch of films set in Mexico, including some that take place in the 1910s and 1920s (which, besides sharing landscapes and other motifs, tend to feature gringos representative of US society and politics, establishing a clear continuity between these realms).

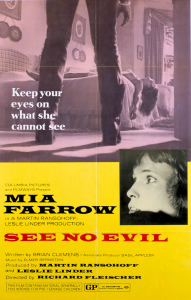

So, yes, unlike film noir, when it comes to westerns, my definition rests on the movies’ setting (time and place) rather than on the specific context in which they were produced (in the case of noir, the post-WWII years). In fact, part of the appeal for me is seeing how different eras recreated the past, from Hollywood classics nostalgically romanticizing national origins to the Italian entries of the 1960s – the so-called ‘spaghetti westerns’ – dirtying up American mythology while reframing the genre’s cinematic style to the sound of Ennio Morricone’s offbeat soundtracks.

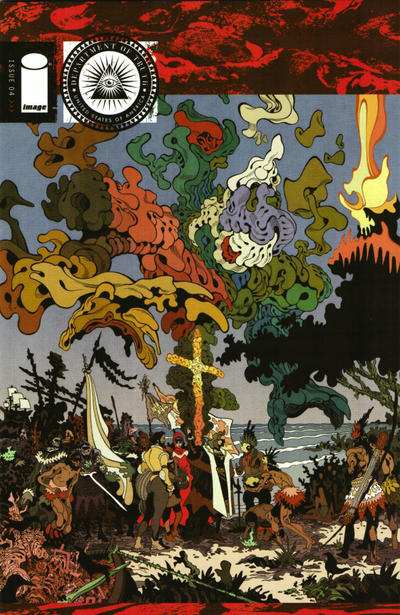

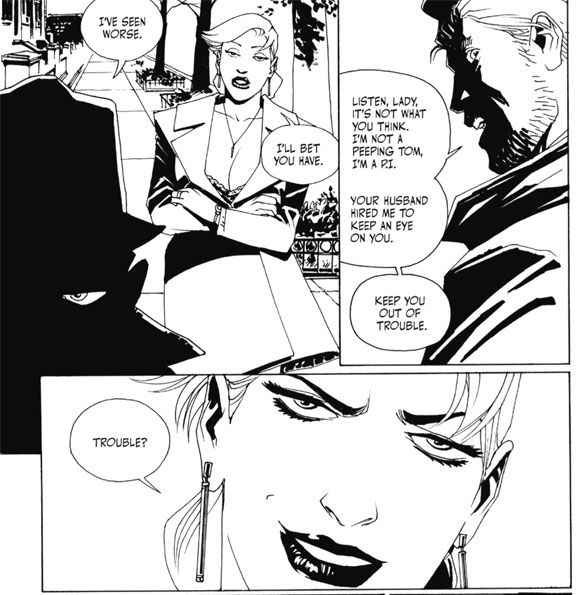

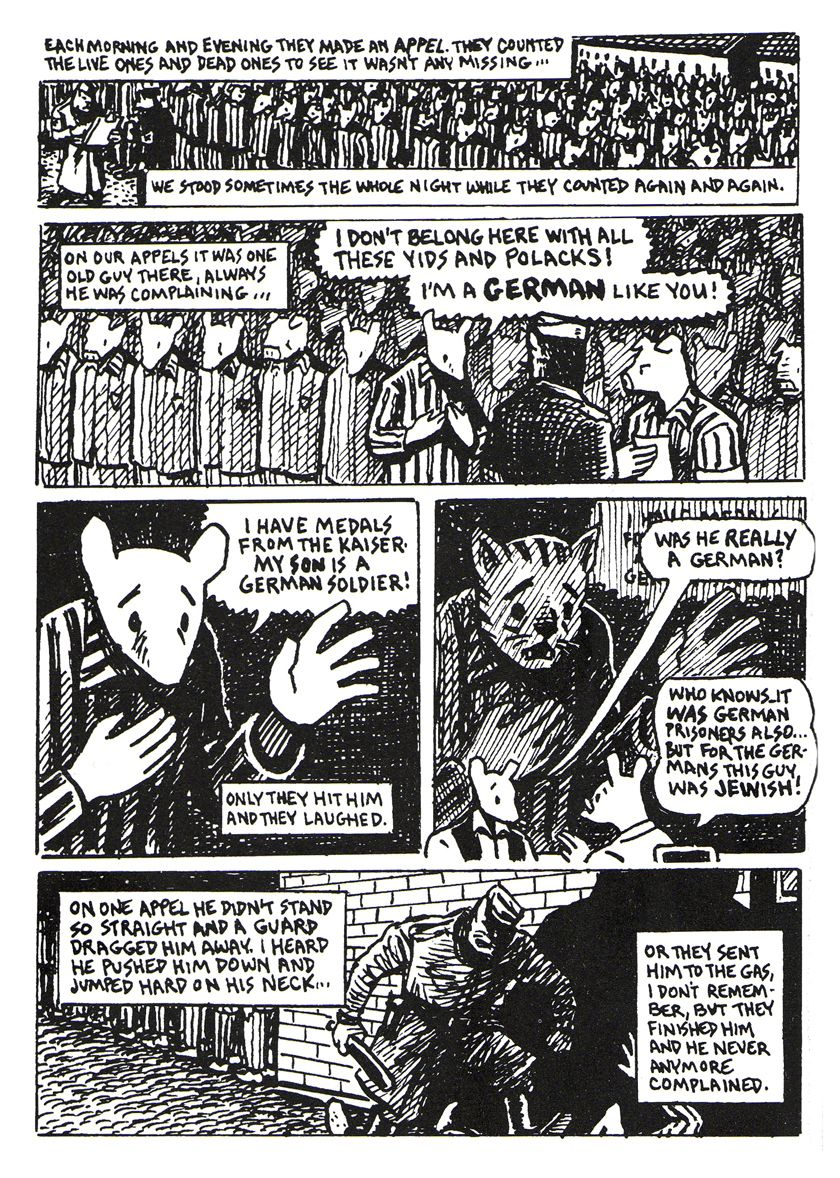

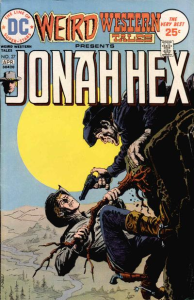

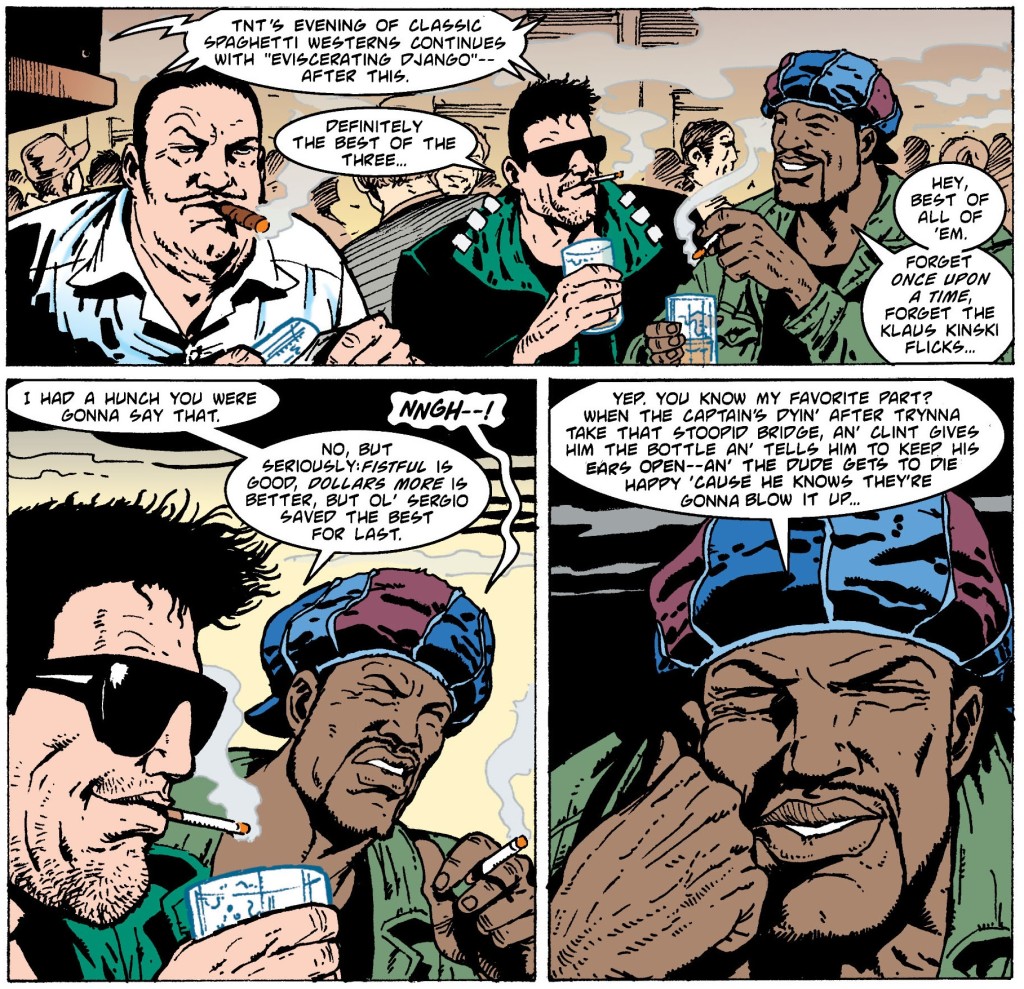

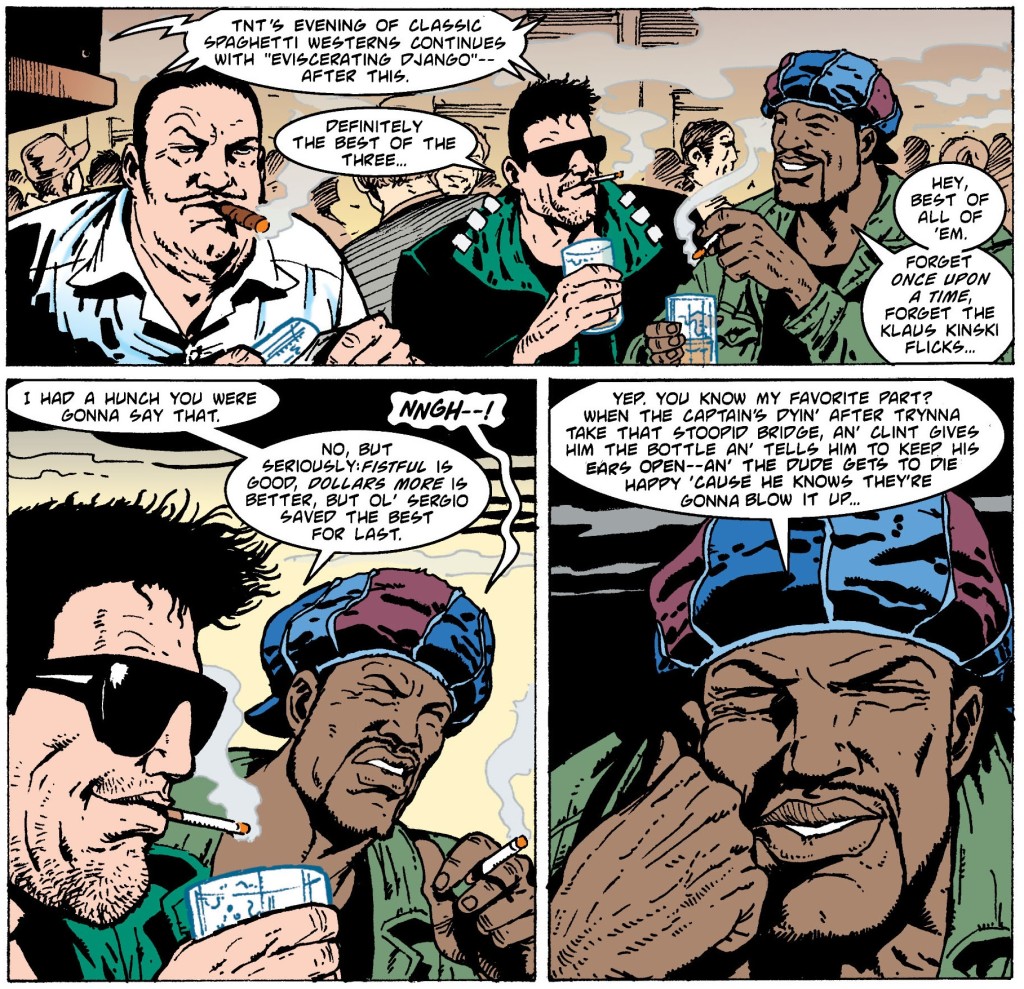

The latter films ended up having a huge influence all over the world, from Japanese chambara pictures (Zatoichi’s Pilgrimage) to Australian post-apocalyptic fiction (Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior). They even had a lasting impact in the USA itself, both on the big and small screens (I’m looking at you, The Mandalorian), as well as in comics (especially those starring Jonah Hex). Hell, there is an entire issue of Hitman devoted to the awesomeness of Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly:

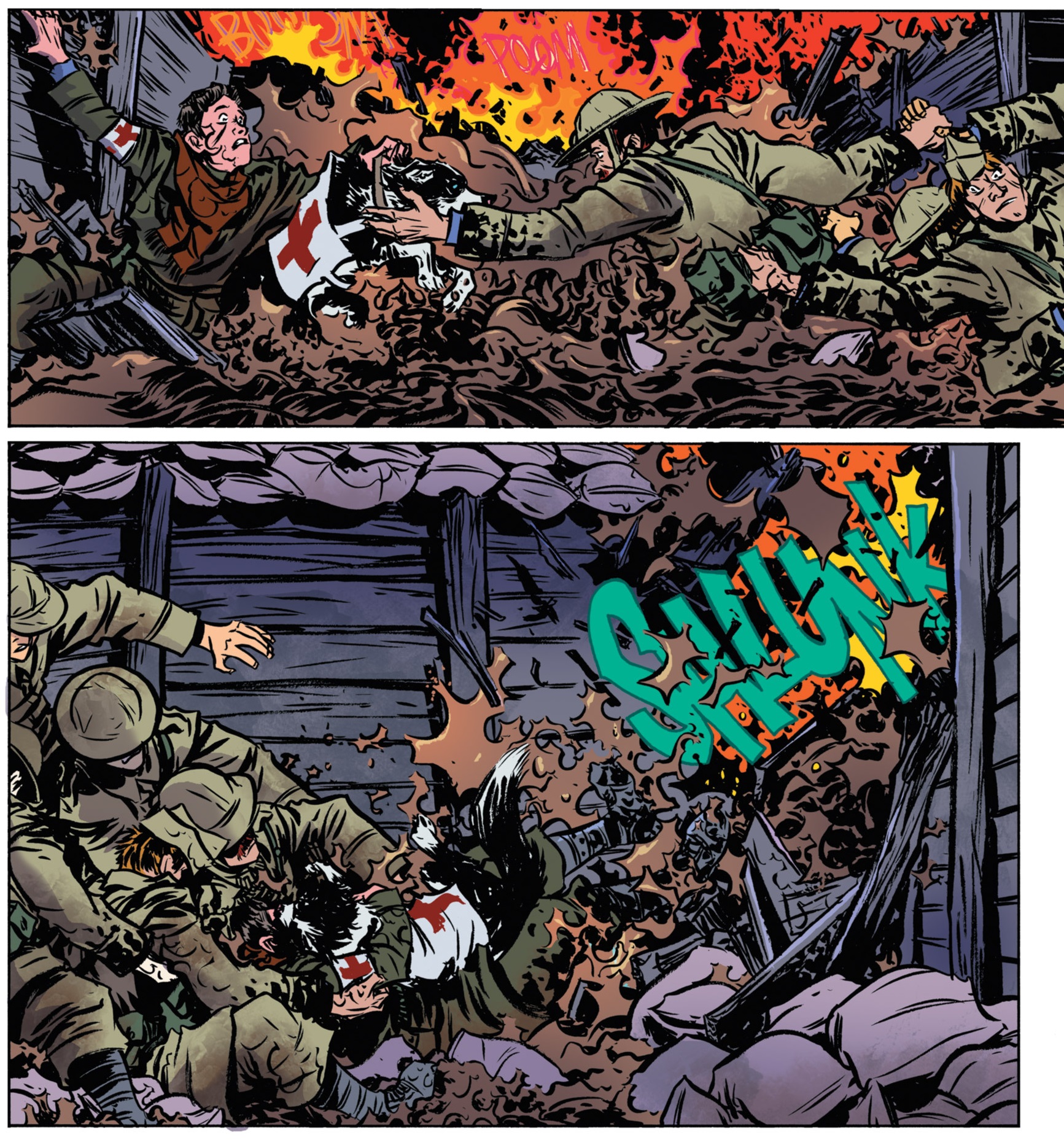

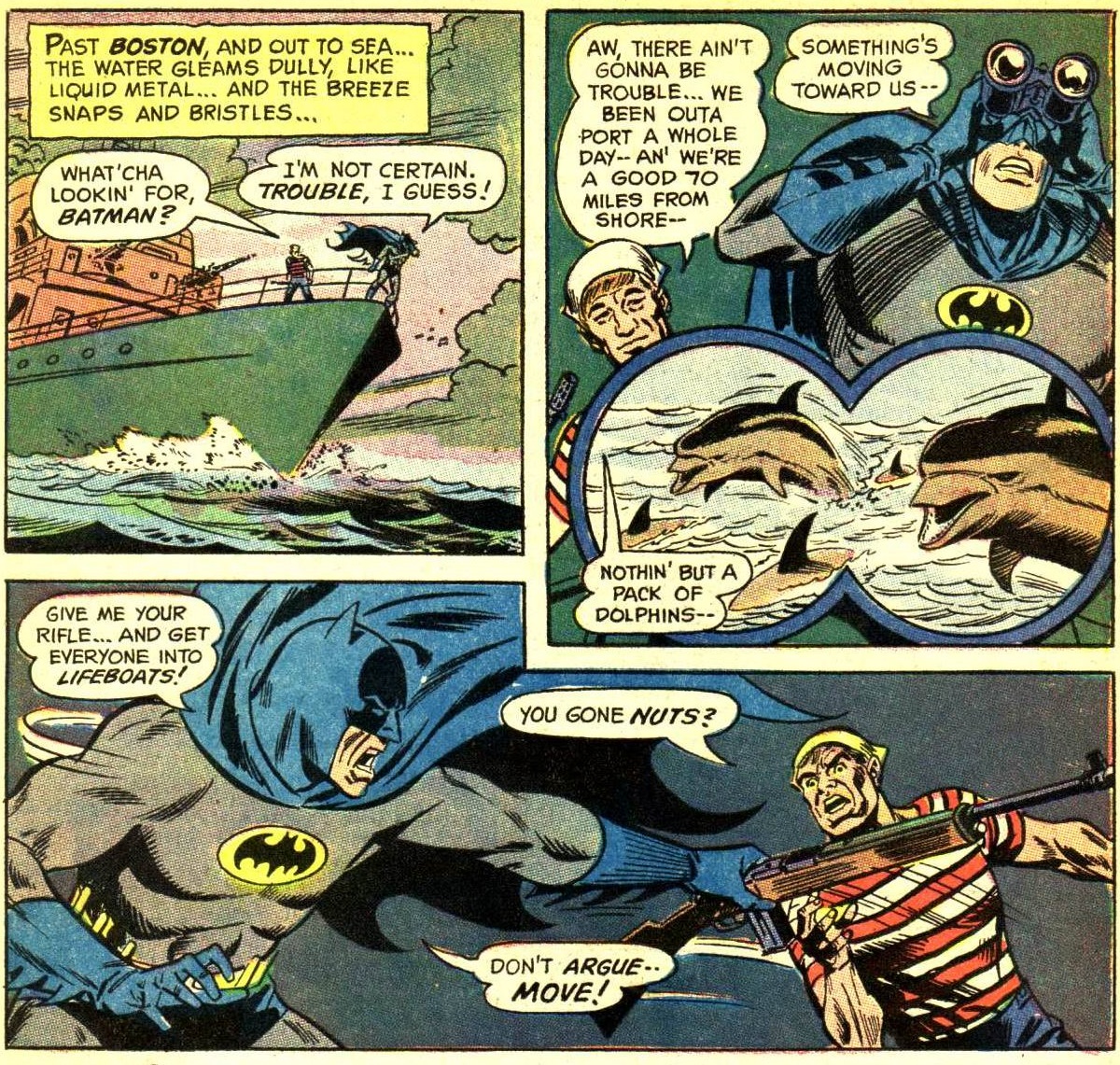

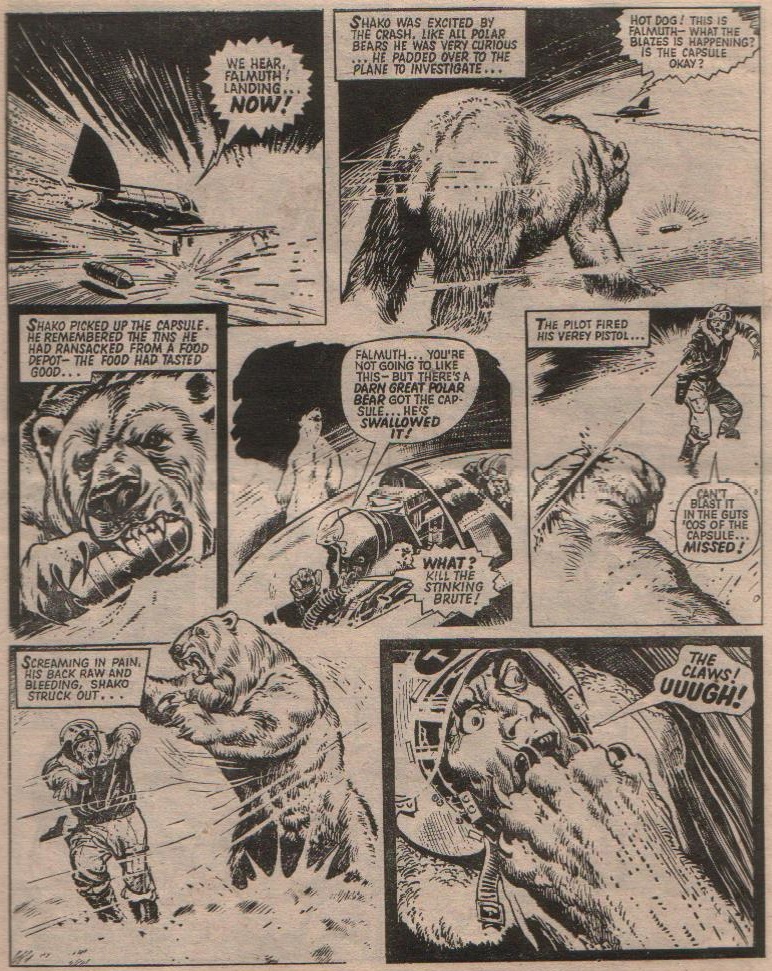

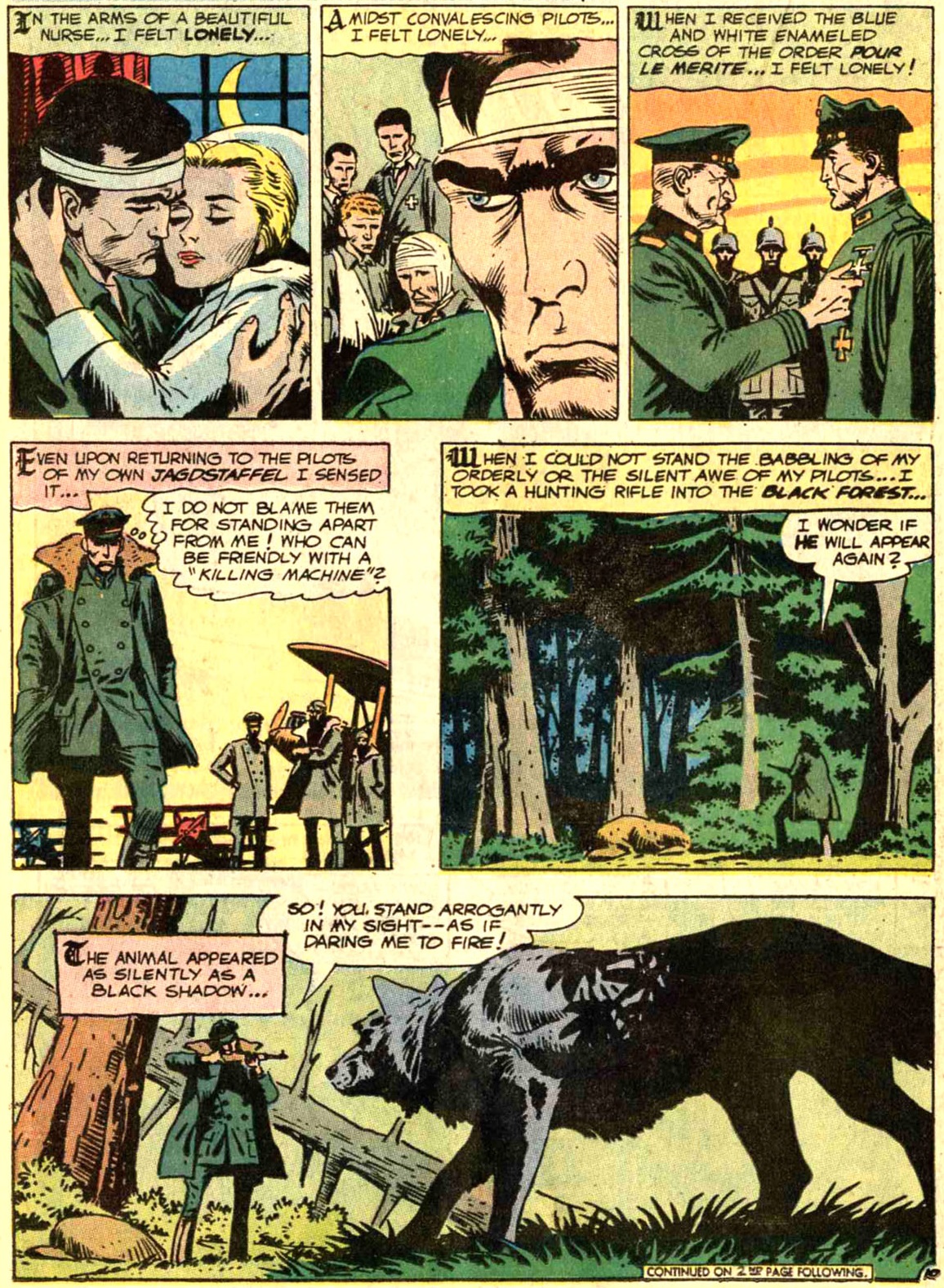

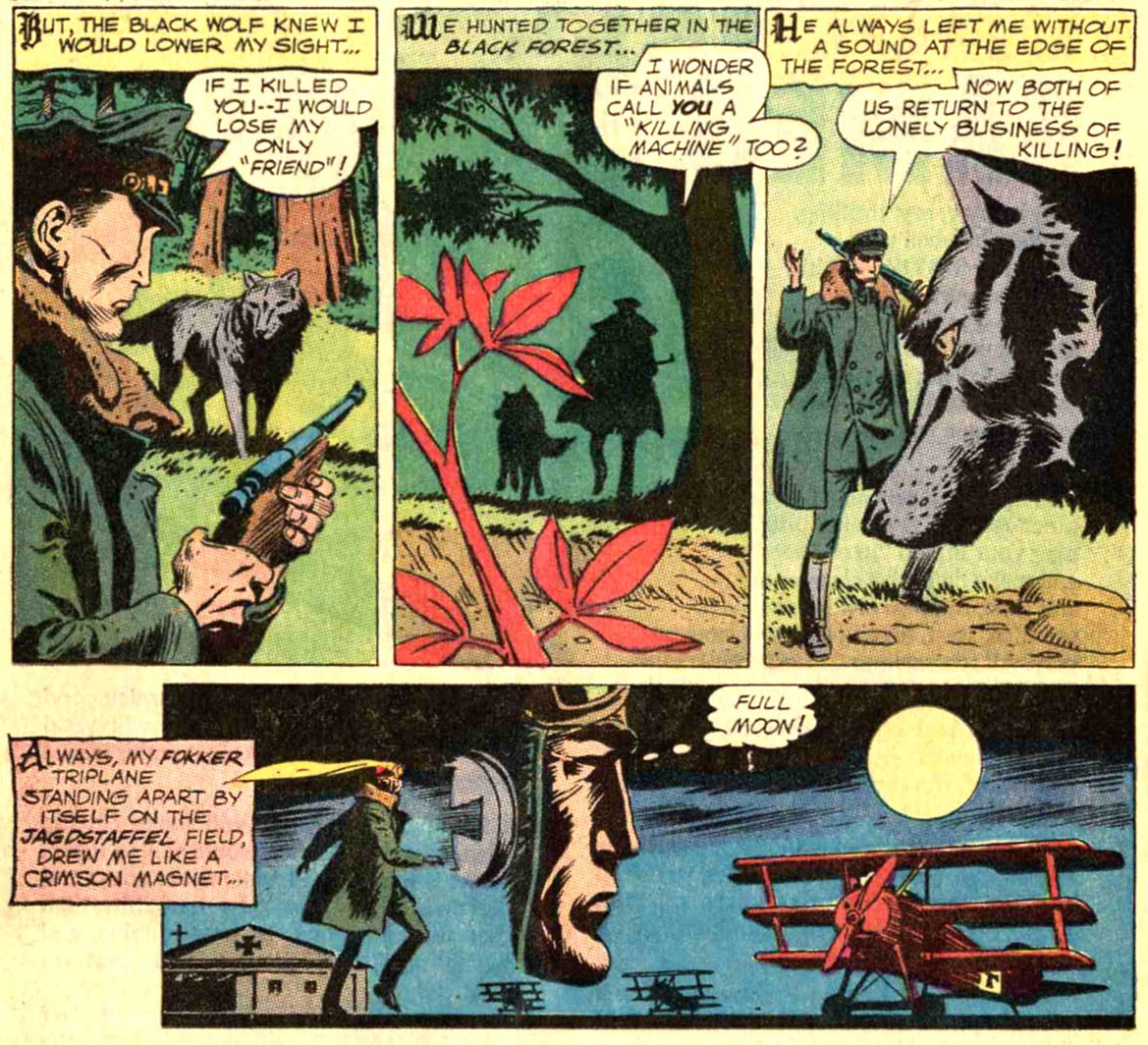

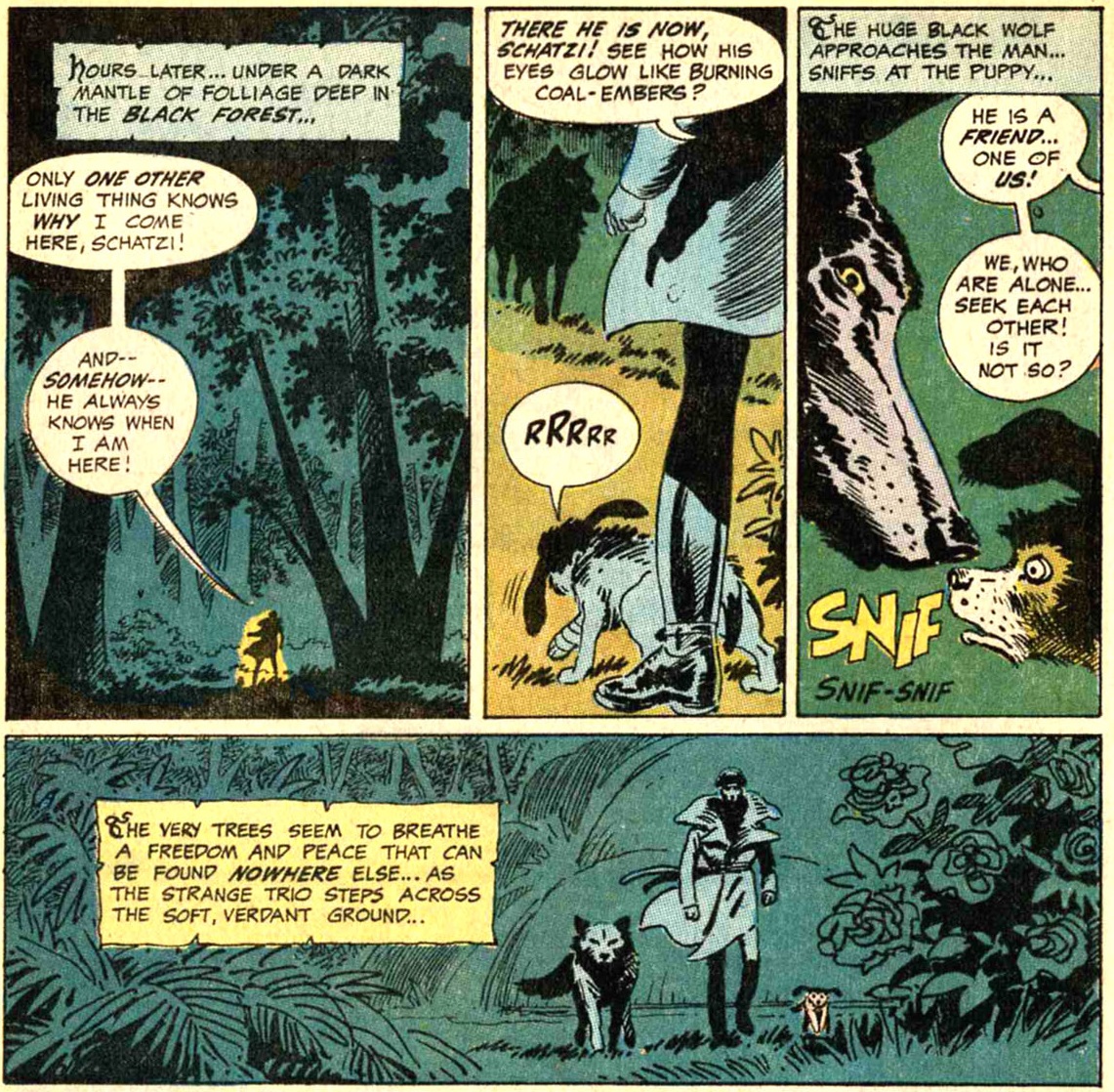

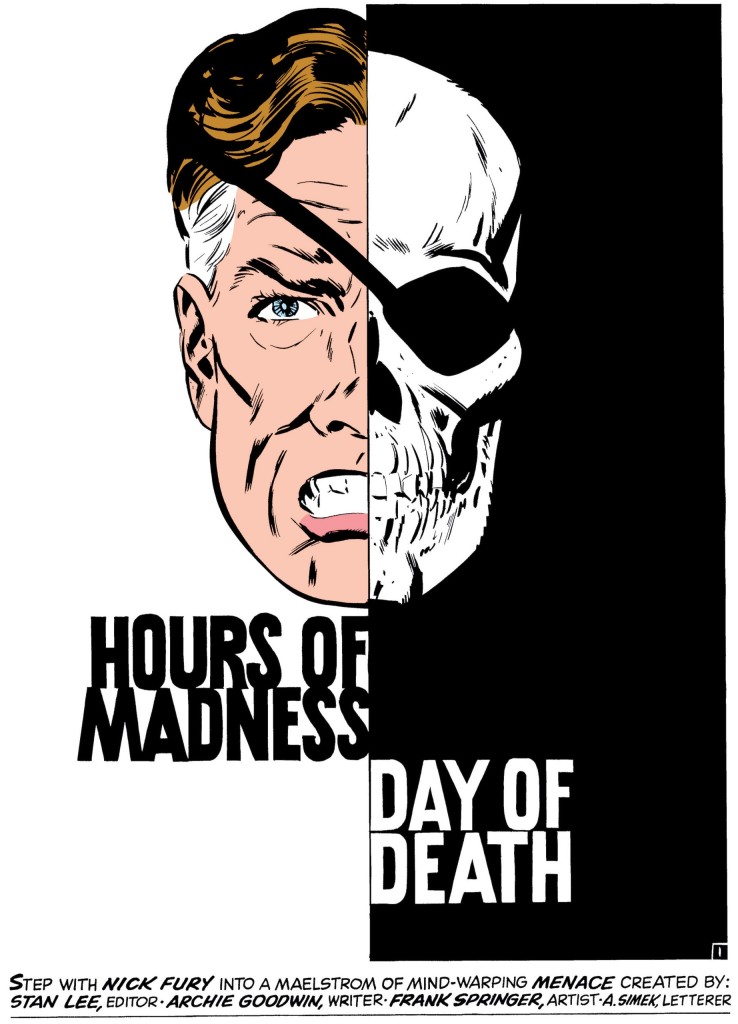

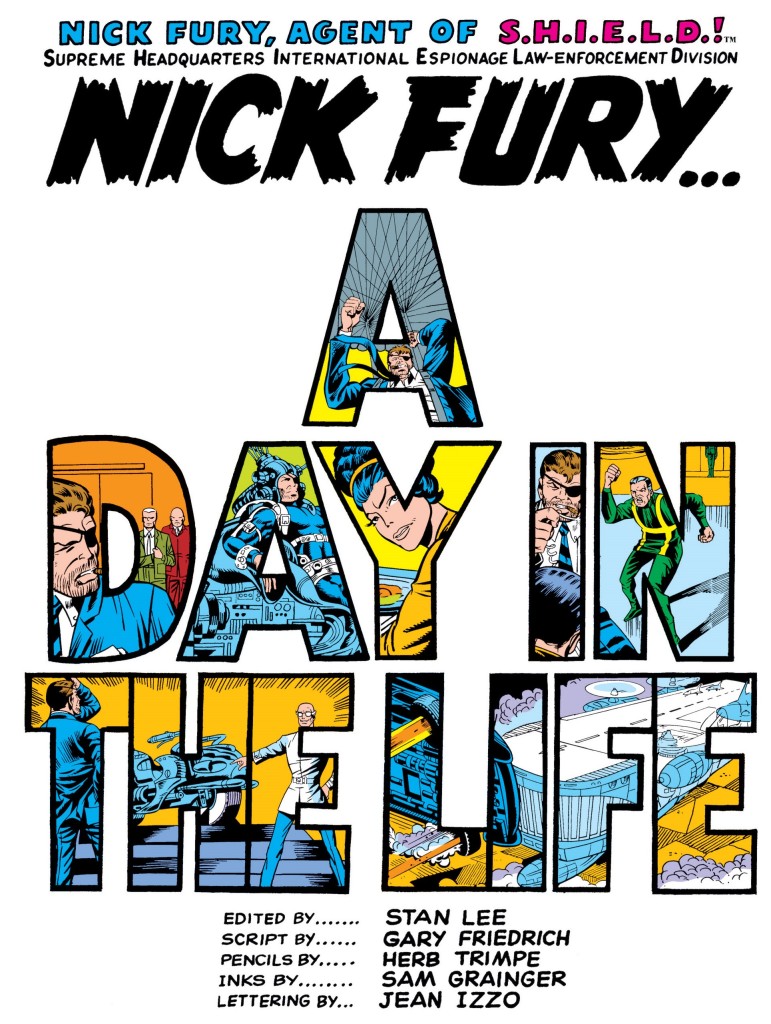

Hitman Annual #1

Hitman Annual #1

In contrast to what I did with the film noir lists, here I’m not very concerned with tone. Most movies below are bound to be two-fisted crime yarns in one form or another, but this list also accommodates spoofs and melodramas. The point is precisely to celebrate all the different ways one can imagine such a narrow slice of history, repeatedly revisiting the same character types (and even the same characters, in the case Wyatt Earp or Pancho Villa…) and the same situations with new lenses.

1. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

1. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (1966)

Tommy Monagham is right. The pioneer of spaghetti westerns, Sergio Leone, had a special knack for balancing iconoclasm with elegiac moments. There are westerns with richer characterization and less histrionic acting, but The Good, the Bad and the Ugly – with its tale of ruthless desperadoes searching for gold against the backdrop of the US Civil War – heightens the intensity of what this kind of movie can be to a level unmatched by anything else I’ve seen. As a bonus, you also get a dark comedy, a war epic, a treasure-hunting adventure, and a parable about capitalism!

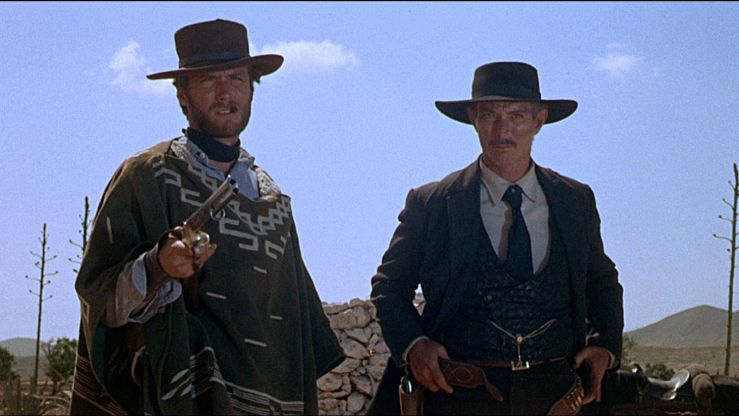

2. For a Few Dollars More (1965)

2. For a Few Dollars More (1965)

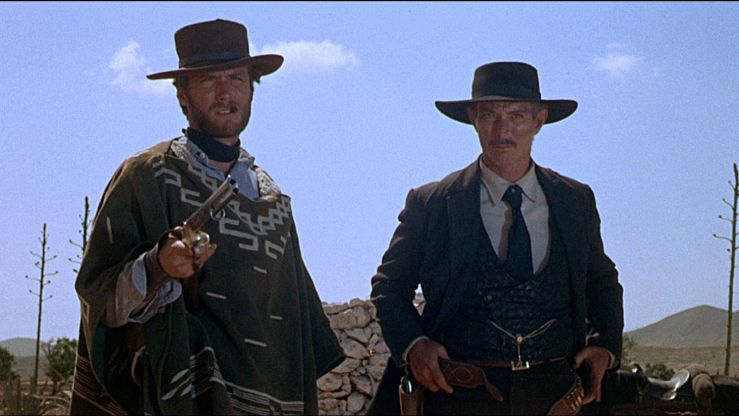

Just before The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Leone had already teamed up with Morricone and tough-guy actors Clint Eastwood and Lee Van Cleef for a horse opera that was just as brilliant (or almost). Like its successor, For a Few Dollars More also concerns a trio of badass killers strategically forging precarious alliances in a maze-like plot, but here the stakes are less grandiose and more intimate, as gradually revealed by a series of brutal flashbacks. There are more memorable set pieces in this movie than in your average dozen westerns combined, from the amusing one-upmanship duel involving Cleef’s hat up to the tense countdown to shoot determined by a pocket watch’s hypnotic music…

3. Stagecoach (1939)

3. Stagecoach (1939)

A marshal, an alcoholic doctor, a prostitute (driven out of town by an intolerant women’s league), a whiskey salesman, a gambler, a corrupt banker, a vengeful outlaw, and the pregnant wife of a cavalry officer (in other words, a selective microcosm of US society) find themselves on a perilous stagecoach trip through territory where the Apaches are on the warpath. Exciting, funny, compassionate (except for the Native Americans), John Ford’s and John Wayne’s first collaboration turned out to be their finest – in fact, it’s the apogee of the Hollywood oater, pulling off the most satisfying version of all the classic tropes. (To be fair, these top titles are all so strong in different ways that, on a day when I’d be more inclined to privilege humanistic characterization over sensorial intensity, Stagecoach could’ve easily made it to the first place instead.)

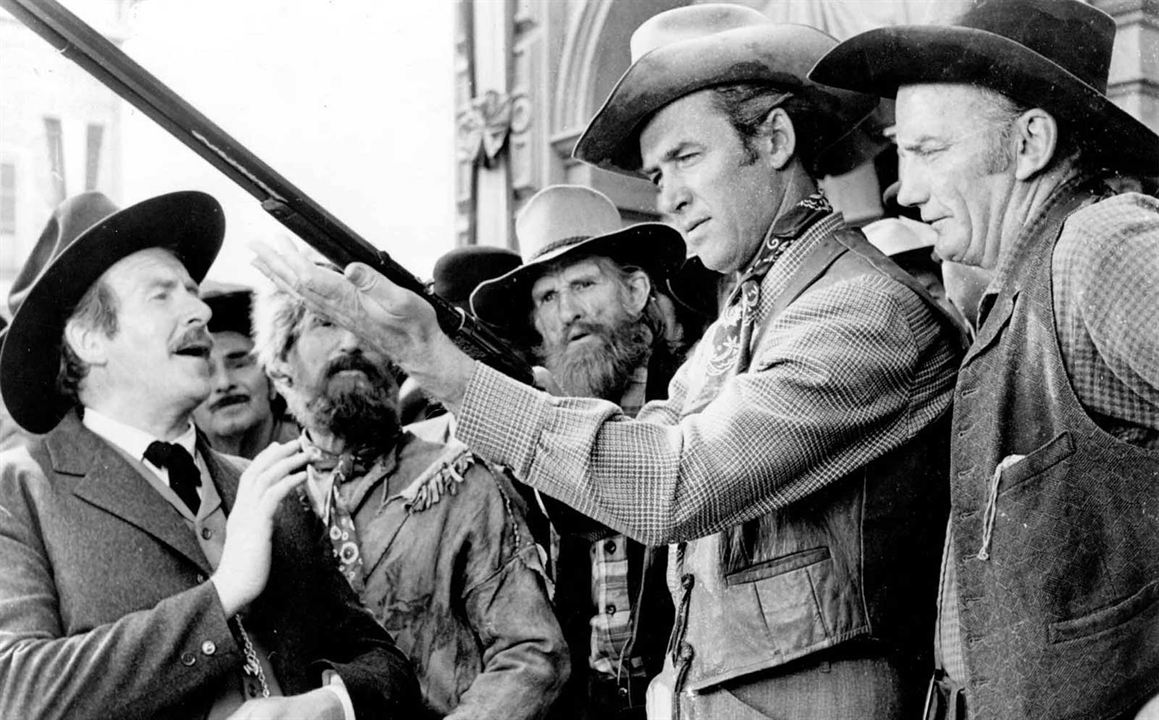

4. The Professionals (1966)

4. The Professionals (1966)

A rich rancher hires four experts (who happen to be played by four of my favorite actors) to rescue his wife (the awesome Claudia Cardinale) after she’s kidnapped by a revolutionary Mexican bandit (Jack Palance with a moustache) – and the mission makes them confront their own lost idealism. Director Richard Brooks may not be as flashy as Leone or Ford, but he is one hell of a screenwriter, pungently nailing each dramatic beat and the knowing banter of seasoned pros. Despite its leftist bent, the witty result must’ve inspired plenty of Chuck Dixon’s men-on-a-mission yarns!

5. Cemetery Without Crosses, aka The Rope and the Colt (1969)

5. Cemetery Without Crosses, aka The Rope and the Colt (1969)

This French entry, about a widow who hires a gunslinger to carry out a cruel revenge against the men who hanged her husband, is a ghostly distillation of genre motifs, executed with minimalistic precision. It’s not all about the form, though: by framing violence (including sexual violence) as an unsentimental ritual, Cemetery without Crosses powerfully conveys the sense that vengeance is a dirty spiral, creating an endless cycle that, rather than give characters – and viewers – closure, continuously plunges them into new forms of tragedy.

6. Winchester ’73 (1950)

6. Winchester ’73 (1950)

More than James Stewart’s avenging rider, the true protagonist of Winchester ’73 is the titular rifle, which gets passed around from owner to owner, serving different purposes in the name of lawlessness and social order, handled by Native Americans as well as the calvary, its trajectory representing both a moral logic of destiny and the historical logic of contingency. Between the hardboiled dialogue and the black & white cinematography, this movie often comes off like a western/film noir hybrid, so of course it is right up my alley.

7. Rio Bravo (1959)

7. Rio Bravo (1959)

A sheriff has to choose between keeping a prisoner in jail or handing him over to a local land baron who wants him free. It’s a Howard Hawks picture, so there isn’t much doubt the sheriff will choose duty, even if his only backup against the baron’s small army is a drunkard, an old cripple, and a kid with a chip on his shoulder. The moody use of music and a clever script (by Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett) further contribute to making Rio Bravo one of the all-time greats.

8. A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

8. A Fistful of Dollars (1964)

In Sergio Leone’s groundbreaking first foray into the genre, Clint Eastwood rides into a Mexican town and sets out to exploit local rivalries, pitting criminals against each other while famously channeling Hammett’s Red Harvest by way of Kurosawa’s Yojimbo. You can sure spot the seeds for the future works not just of Leone, but also of the likes of Quentin Tarantino and Garth Ennis (both of which made careers out of trying to recreate the coolness of that monologue about the mule).

9. High Noon (1952)

9. High Noon (1952)

Taking place in real time, High Noon follows the countdown to the arrival of the noon train, which will bring into town a released criminal set on revenge against the local marshal, who desperately tries to recruit people to stand alongside him (while also fighting with his pacifist Quaker wife). Although some have read in this a Cold War parable about the USA’s need to mobilize against the foreign threat posed by incoming communism, legend has it the whole thing was actually dramatizing the breakdown of solidarity in Hollywood surrounding the HUAC hearings and the subsequent blacklist (i.e. a reading on the complete opposite end of the political spectrum). Regardless, the movie works on a more direct level as well, conjuring up a quintessential melodramatic mix of tension, isolation, and despair.

10. Ride Lonesome (1959)

10. Ride Lonesome (1959)

Superficially, Ride Lonesome is just another tale about a group of distrustful people coming together to face a succession of dangers while traveling through a desolate landscape. It all comes down to the execution: the director-writer-star team of Budd Boetticher, Burt Kennedy, and Randolph Scott perfected the art of simple, taut storytelling in which the characters’ psychology and an engrossing narrative beautifully emerge without much of a fuss. Here, they are helped by a particularly sturdy supporting cast.

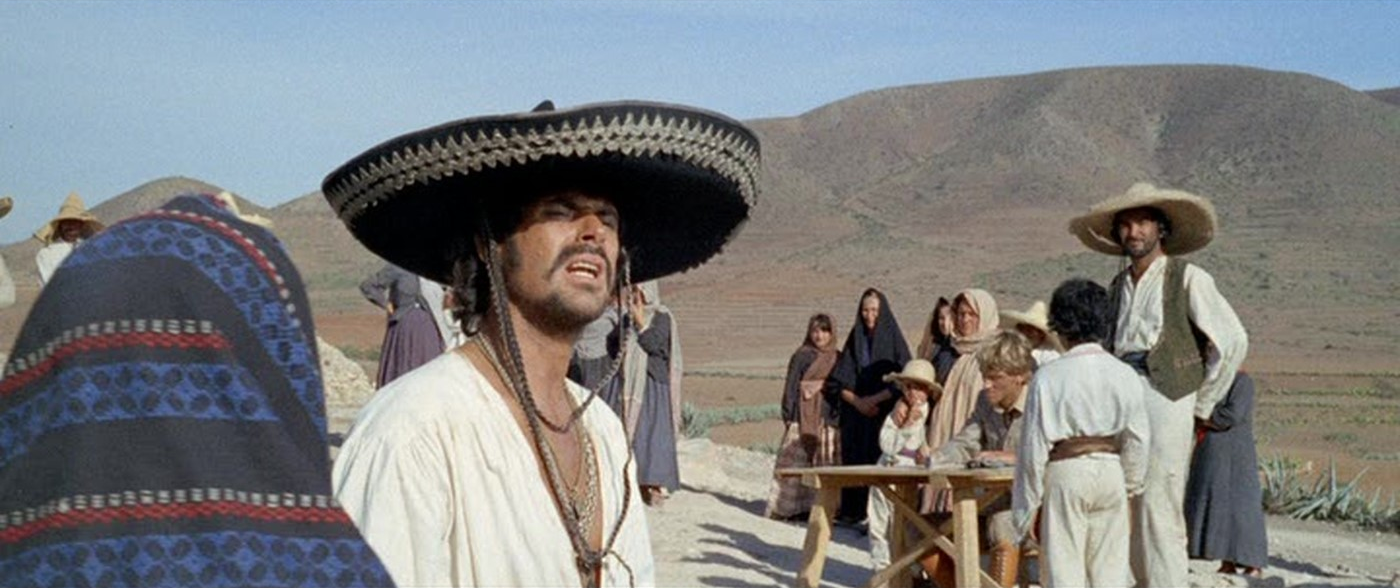

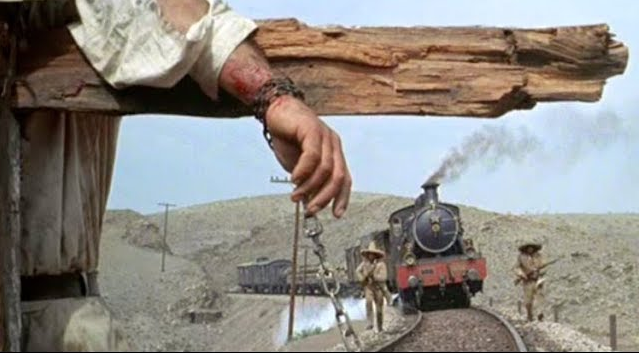

11. A Bullet for the General (1966)

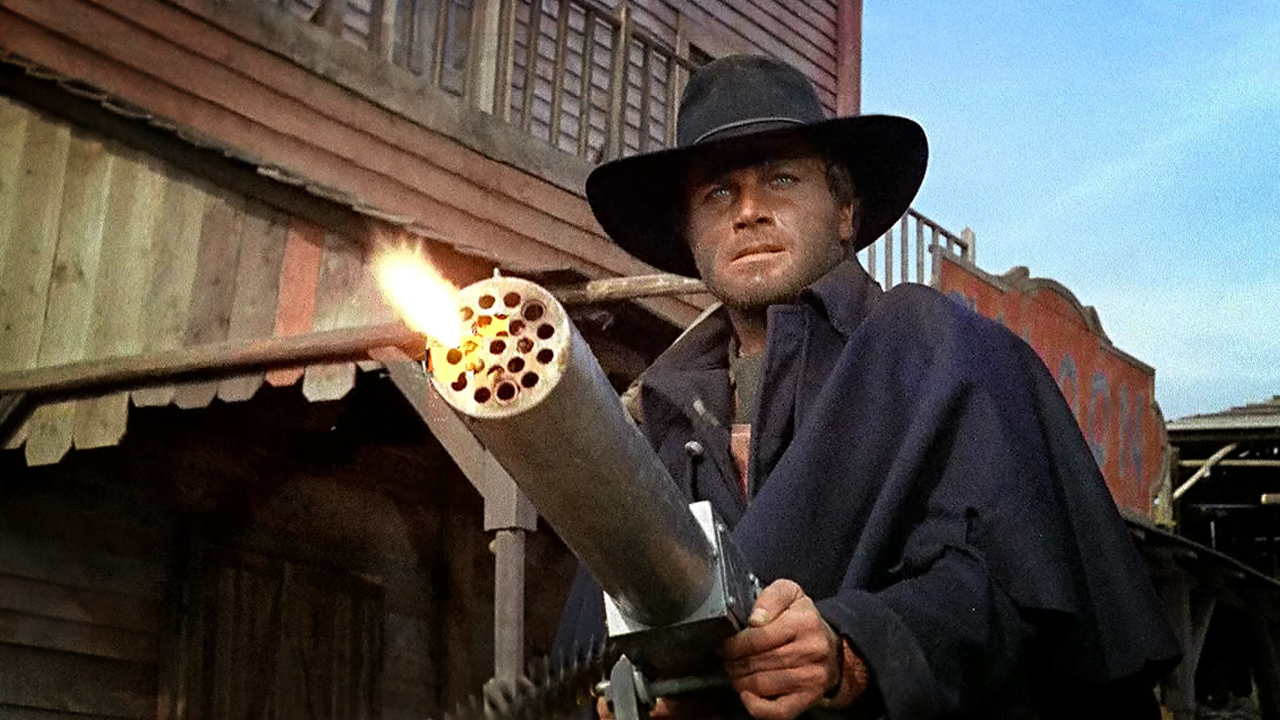

11. A Bullet for the General (1966)

Unless you count the American The Professionals (which premiered a month before), this was the pioneer of the ‘Zapata Western’ subgenre, a string of politically charged European productions about adventures set in the Mexican Revolution, presented as incredibly messy even by Marxist filmmakers who sympathized with the peasants’ cause (these vicious bandits are a world away from any benign image of pure-hearted poor). Vibrant yet episodic, A Bullet for the General is an anti-imperialist epic shot against impressive vistas full of authentic-looking extras and chaos… Plus, Klaus Kinski plays a revolutionary priest who both kills (a lot) and prays for the dead.

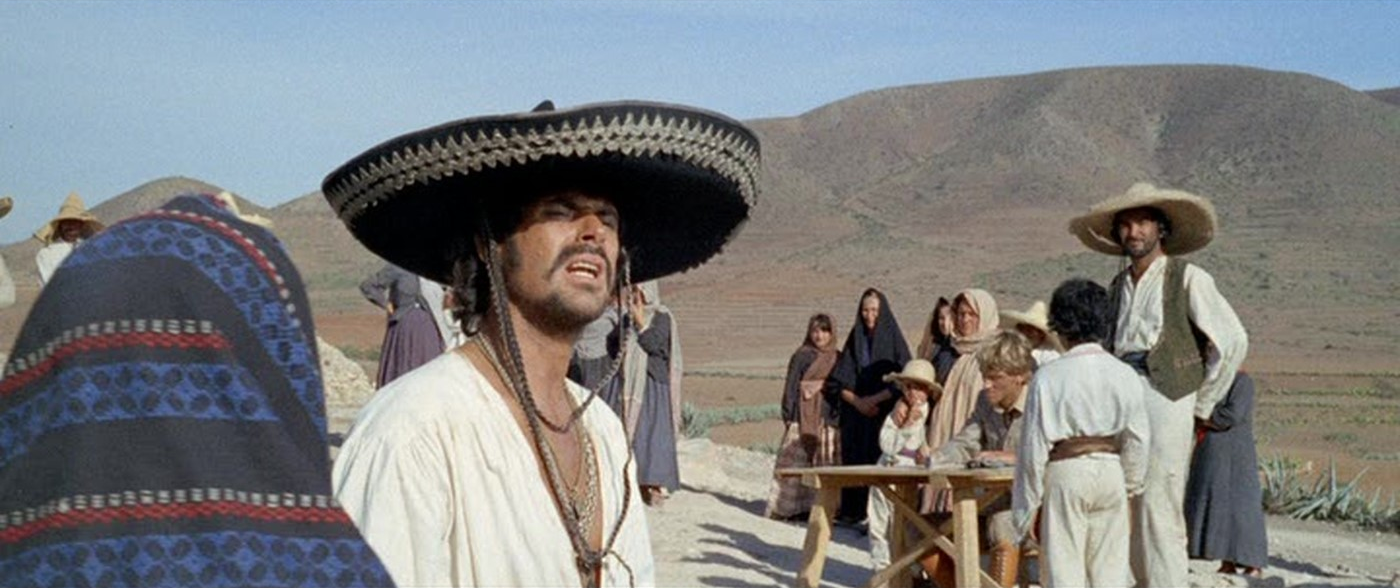

12. Tepepa, aka Blood and Guns (1969)

12. Tepepa, aka Blood and Guns (1969)

The main rival for the position of best Zapata Western, Tepepa provocatively inverts the narrative thrust of For a Few Dollars More (placing the villain in the role of hero) in order to question whether or not revolutionary ideals should be above everything else. Communist screenwriter Franco Solinas borrows from his own script for A Bullet for the General (‘Señor, do you like Mexico?’ ‘No.’), but by now the disillusioned fallout from the May ’68 protests must’ve been ringing in the filmmakers’ minds, so the politics are even more ethically discomfiting, leading to a twisted finale that can be seen as either harshly ironic or perversely sincere… The movie also delivers on the technical front, often coming off like a haunting audiovisual poem. Plus, Orson Welles.

13. Blazing Saddles (1974)

13. Blazing Saddles (1974)

In this live-action Looney Tunes cartoon, a conniving attorney general tries to force the residents of Rock Ridge out of town (in order to reroute a railroad) by appointing a black sheriff and relying on the locals’ racism to generate chaos. Granted, when I first watched this as a kid and thought it was the most hilarious movie ever, I was less sensitive about the many un-PC jokes and stereotypes (as is often the case with comedy, there is a thin line between mocking prejudice and enacting its harmful force, flirting with both pleasure and displeasure). That said, everyone seems to be having a blast – starting with Cleavon Little in the leading role – and their mischievous enthusiasm is quite infectious. On top of the broad gags and social satire, Mel Brooks employs (and cheerfully destroys) Hollywood’s stock sets and character actors to wreck anarchy upon the classic western, giving it a suitably disrespectful send-off (nobody was able to unconsciously film it in the same way again, just like with Watchmen and superheroes). In a genre that preys on intertextuality, such a merciless metafictional deconstruction earns Blazing Saddles a high position on this list.

14. The Hateful Eight (2015)

14. The Hateful Eight (2015)

Quentin Tarantino’s own foul-mouthed treaty on racial hatred in the US is morally muddier and more provocatively cynical than Blazing Saddles, building on that old George Carlin line: ‘Bullshit is the glue that binds us as a nation.’ There are no heroes here, only loathsome, grotesque characters acting out various traditions of American grudges and prejudices while stuck together during a blizzard (in the end, it’s hatred of women that brings the surviving men together). I place it above a handful of foundational classics, once again reflecting personal taste: I just get such a kick out the kind of pitch-black humor that’s all over The Hateful Eight’s dialogue, violence, and performances (especially those by Samuel L. Jackson, Kurt Russel, and Jennifer Jason Leigh).

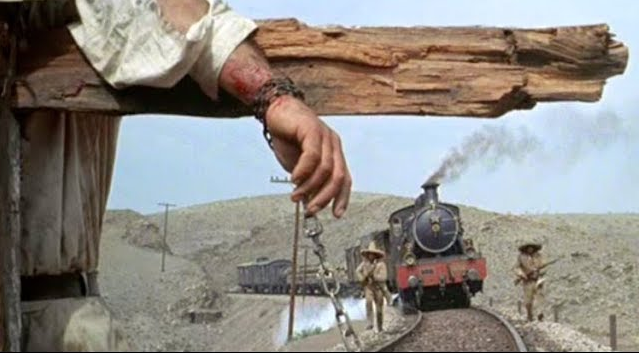

15. Duck, You Sucker!, aka A Fistful of Dynamite, aka Once Upon a Time… the Revolution (1971)

15. Duck, You Sucker!, aka A Fistful of Dynamite, aka Once Upon a Time… the Revolution (1971)

Sergio Leone’s own contribution to – or perhaps satire of – the Zapata Western cycle is a visual tour-de-force bursting with energy and irreverence (from the very first shot)… and steeped in bitter cynicism. Duck, You Sucker! depicts revolutionary class struggle as ferocious and unpleasant, but also riveting, often stirring up uncomfortable contradictory emotions. Despite a derivative flashback structure and some objectionable content (again, the peasants do some ugly shit in retaliation for their oppression), I find it a more rewarding watch than Leone’s acclaimed Once Upon a Time in the West.

16. Law and Order (1932)

16. Law and Order (1932)

I had to include at least one movie inspired by the battle at the O.K. Corral, given that there are so many great ones out there. My preference goes for the very first film to tackle this historical episode, a fast-paced pre-Code gem starring Walter Huston and scripted by his son (the first of their two collaborations on this list), whose smart writing is full of punchy and ironic character moments, vividly brought to the screen. Besides all the authentic-looking details (the story is set fifty years before the movie was made, so there was still a living memory of, for example, the physical routines one did when entering a grimy hotel room…), Law and Order is also interesting for the way it engages with early 1930s’ concerns about guns and gangsters: it opens with a montage about how the country was forged through violence and sticks with a bitterly disenchanted look at both illegal and state-sanctioned acts of killing right up until the pessimistic ending. Since there had already been hundreds of (mostly silent) westerns before, there is a case to be made that this is an early – and stark – example of genre revisionism.

17. The Wild Bunch (1969)

17. The Wild Bunch (1969)

An aging gang of macho outlaws take refuge in 1913 Mexico, where they end up working for a corrupt general. This American answer to the Zapata Western subgenre is just as packed with masterfully edited raucous carnage as its European counterparts, but with greater emphasis on writer-director Sam Peckinpah’s pet themes of honor, loyalty, and growing old in a world where you no longer fit in.

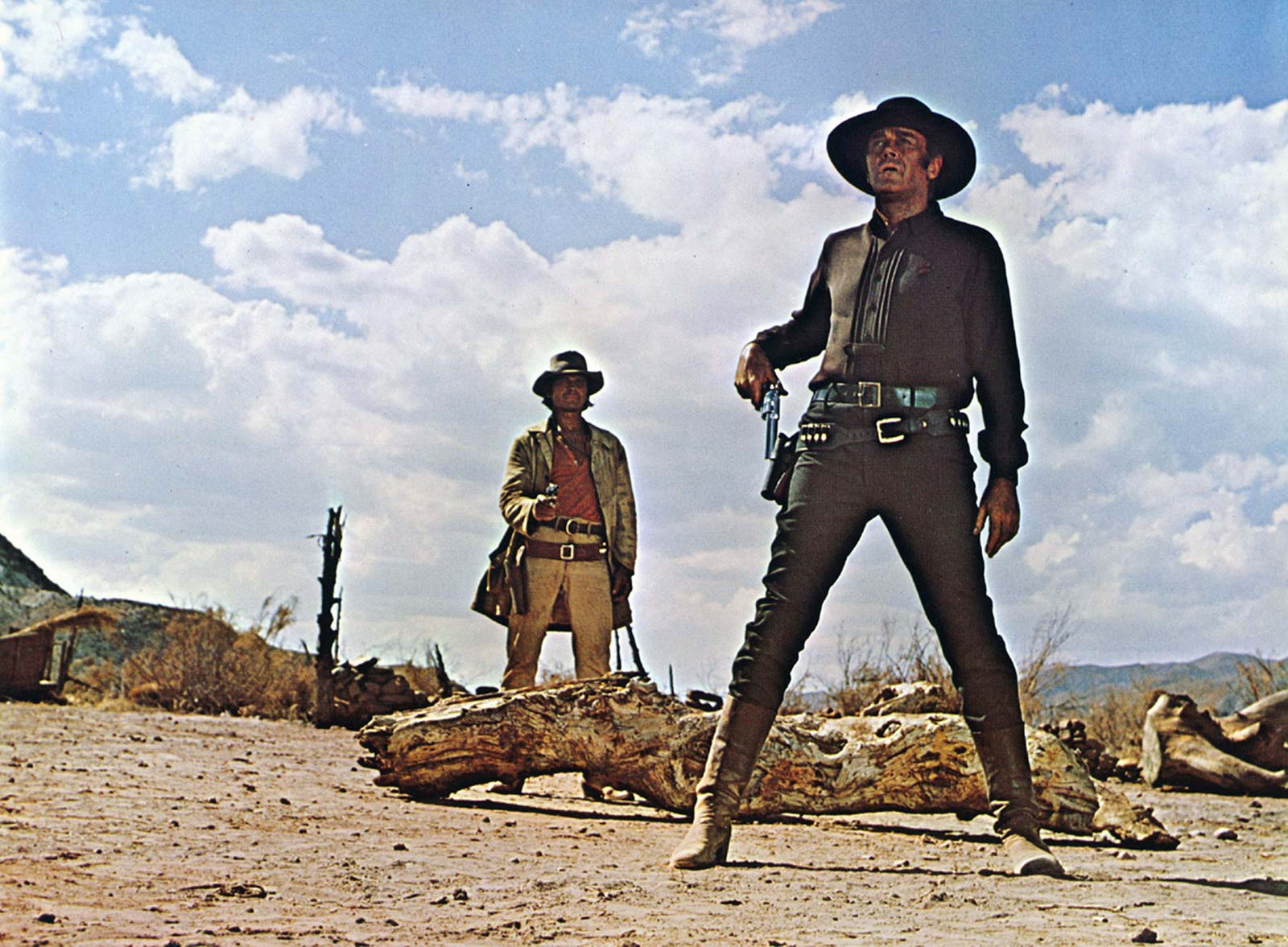

18. Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

18. Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

The western to end all westerns, this luscious epic tells an unhurried and operatic saga about a web of interlinked conflicts surroundind a land battle over the construction of a railroad, exaggerating traditional elements almost to the point of caricature. It’s also a meta-western, opening with brilliant riffs on High Noon and Shane and knowingly drawing on the genre’s dense history, most famously by casting Henry Fonda against type.

19. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

19. The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962)

A respected senator comes to the town of Shinbone to mourn an old acquaintance, leading to a lengthy flashback that reveals the hidden historical significance of – you guessed it – the man who shot Liberty Valance (whose gang used to terrorize Shinbone). Ford’s forceful, ultimate statement about the transition from the Wild West into a more civilized era links this process to evolving approaches to manliness as well as to the notion that coexistence is built on useful lies (for an R-rated riff on the same topic, see The Hateful Eight).

20. Meek’s Cutoff (2010)

20. Meek’s Cutoff (2010)

Following a small group of settlers on the Oregon Trail as they go about their tedious labors, get lost, despair, and argue about what to do with a native they meet in the desert, Kelly Reichardt has a crafted a truly original and gorgeous – yet devastatingly unromanticized – take on the sort of material we’ve seen countless times before. Patiently contemplative and paired down in terms of plot and dialogue, Meek’s Cutoff takes its time to get going, but it eerily enwraps you in an atmosphere that feels often menacing, occasionally amusing, and somehow both grounded and dreamy.

21. Unforgiven (1992)

21. Unforgiven (1992)

Although not as radical as Meek’s Cutoff, this is also a committedly revisionist western, one where Clint Eastwood (who directed it) plays with his persona in the form of an over-the-hill gunfighter compelled to come out of retirement. Grim and gritty, subverting genre conventions with proto-realistic touches, I’ve always looked at Unforgiven as westerns’ version of The Dark Knight Returns, albeit without that comic’s parodic vibe. (Eastwood has spent the subsequent thirty years revisiting variations of this subject, so it’s interesting to consider Unforgiven not just as a closing chapter in his western career, but also as the opening salvo of his ongoing meditation about the place of old-school alpha males in the modern world.)

22. The Great Silence (1968)

22. The Great Silence (1968)

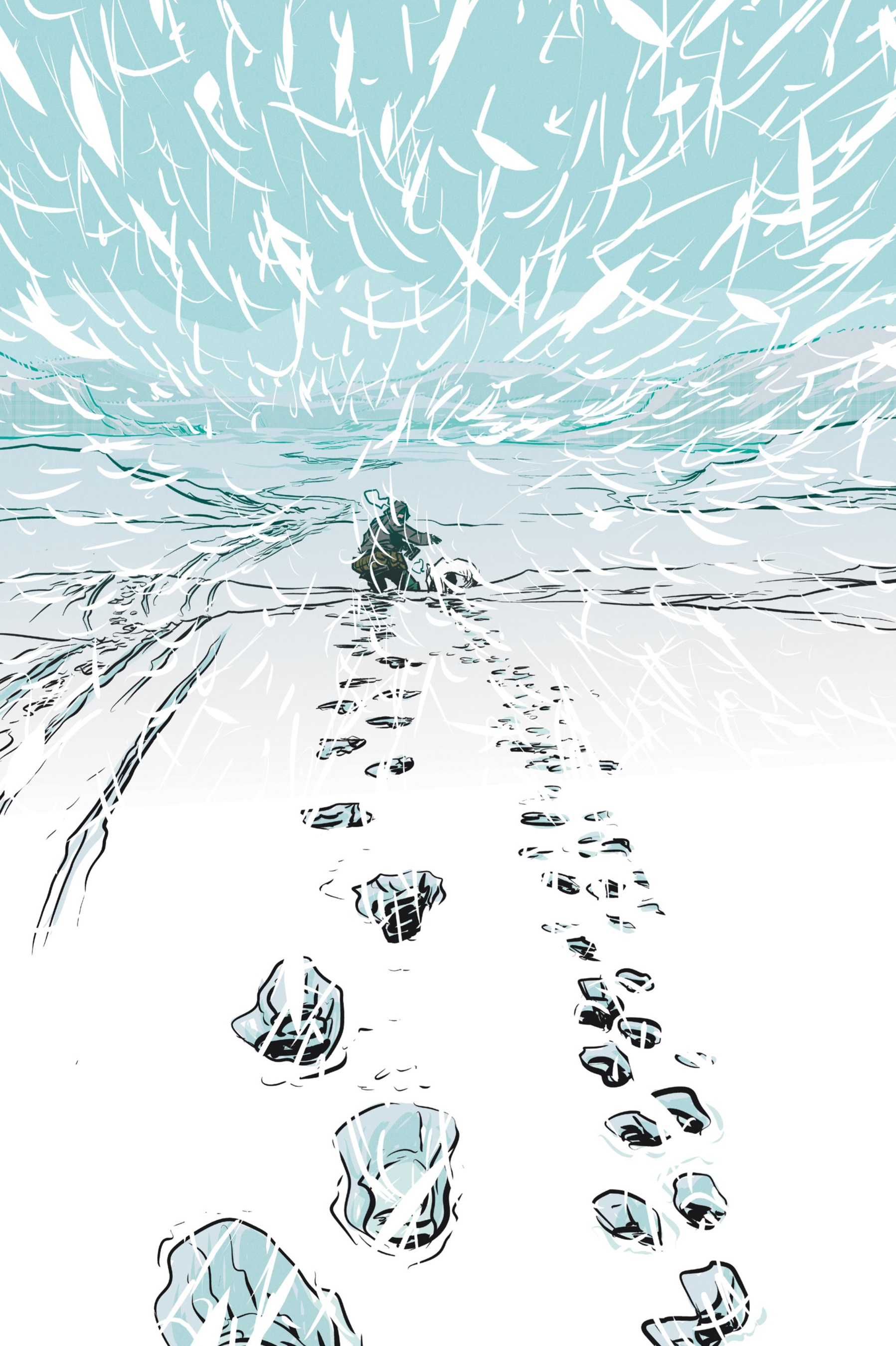

A mute gunslinger (hence the title) faces off against a gang of bounty hunters (led by Klaus Kinski at his most sinister) who have been slaughtering local thieves waiting for an amnesty. You’ve seen many of the story beats before, but you’ve probably never seen them quite like this – set in Utah during a severe blizzard, much of the action is covered in snow and you can feel the damn cold taking over the characters (literally and metaphorically). The result is breathtaking, despite also being one of the nastiest and most downbeat entries in the genre’s entire canon, macabrely depicting the nitty-gritty of the business of killing people for pay. And what an ending!

23. Red River (1948)

23. Red River (1948)

Besides being a dramatically engaging reconstruction of the impressive hardships of earlier cattle drives – and of the establishment of the Chisholm Trail (linking Texas to Kansas) in particular – Red River builds into a poignant examination of leadership, pitting John Wayne’s authoritarianism against Montgomery Clift’s more liberal approach.

24. 3:10 to Yuma (1957)

24. 3:10 to Yuma (1957)

A nail-biting duel of wills between an honored cowboy and a charismatic robber, as the former tries to bring the latter to justice against shrinking odds. In theory, the linear narrative and the poetic ending could’ve made 3:10 to Yuma feel simplistic and even corny, but the movie displays such command of the form, compellingly suggesting hidden levels of ambiguity and psychological depth, that the result is like an oddly touching morality play.

25. Django Unchained (2012)

25. Django Unchained (2012)

Although more clear-cut than The Hateful Eight, Tarantino’s first venture into the genre was also a riot, casting Jamie Foxx as a slave-turned-bounty-hunter working his way back to his loved one, one massacre at a time. I’ve written about it before: ‘this incendiary mix of spaghetti western and blaxploitation took the revenge fantasy format of Kill Bill, Death Proof, and Inglourious Basterds to a new extreme by applying it to America’s history of slavery. Like its predecessors, the film went for subversive entertainment in the shape of a rollicking ballet of gory catharses and shocking anti-climaxes, but it struck a deeper nerve in the Obama-era zeitgeist of racial identity politics. […] This left critics to puzzle over what’s more politically incorrect – the notion that the movie is a tasteless genre exercise or the disturbing implications of taking it seriously? Me, I think the moral confusion is part of the appeal.’

26. Day of the Outlaw (1959)

26. Day of the Outlaw (1959)

Another entry into the rare subgenre of the ‘winter western,’ Day of the Outlaw looks even more striking than The Hateful Eight and The Great Silence thanks to its stark black & white, which makes everything look dark against the snow. Along with the visual – and inescapably symbolic – contrast between darkness and clarity, we get a genuinely harrowing slice of psychological horror, pitting cattlemen against farmers, militarized outlaws against powerless civilians, and lustful men against desperate women… The natural landscape may look slushy and freezing cold, but it’s the urban settlement that comes across as truly inhospitable and unforgiving.

27. Union Pacific (1939)

27. Union Pacific (1939)

The construction of the Union Pacific Railroad is turned into a rousing spectacle, as a businessman bets in the stock market against the enterprise (yep, already at the time) and, just to make sure, hires an intermediary to keep sabotaging the proceedings, namely by supplying vices to the workers along the track. This is only one of many subplots in a picture that blends charming romance, rambunctious comedy, action-adventure, and political polemics. Granted, even by the genre’s generous standards of nationalist fabulation, this Cecil B. DeMille epic must take some kind of prize (for one thing, its account of the construction work manages to miss the thousands of Chinese immigrants…), but that only makes Union Pacific an even more curious object, lending itself to multiple layers of historical analysis on top of the enjoyable surface.

28. Navajo Joe (1966)

28. Navajo Joe (1966)

An exhilarating barrage of violent action, accompanied by an unforgettable soundtrack, as a Navajo anti-hero (Burt Reynolds, believe it or not) takes bloody revenge on a gang of scalp-hunters. Along with The Great Silence and Django, this gloriously bizarre picture offers further proof that Sergio Corbucci must’ve been one of the core directors shaping Tarantino’s DNA.

29. The Gunfighter (1950)

29. The Gunfighter (1950)

A day in the life of Jimmy Ringo, a faster-than-light gunfighter who just wants to be left alone but has to keep facing young punks trying to prove themselves against him… Besides capturing the melancholia of a character who can’t seem to move on from his past and to escape his fate, The Gunfighter – as pointed out by David Eldridge in Hollywood’s History Films – is yet another movie about the difficult passing of the Old West into modern society, with Ringo as a haunted victim of his own legend, ‘unable to make the transition to a safe, domestic life.’

30. The Naked Spur (1953)

30. The Naked Spur (1953)

Like Winchester ’73, this is one of a handful of hard-hitting collaborations between James Stewart and director Anthony Mann, this time in splendid Technicolor. Stewart is now a bounty hunter who joins forces with a couple of strangers in order to bring a wanted outlaw across the hazardous wilderness, but the latter keeps playing mind games on them (and on his girlfriend, who comes along), sowing distrust among the group. Mann’s signature moves of placing characters constantly at the mercy of natural elements and replacing the genre’s typical horizontal confrontations (gunslingers starring at each other across a town’s main street) with vertical ones (guy at the top of a mountain shooting at the ones below) illustrates the point that men’s fates are shaped by their surroundings and determined by their vantage points, even if wits and determination can go a long way…

31. Vera Cruz (1954)

31. Vera Cruz (1954)

An unabashedly fun romp about the misadventures of a couple of North Americans – one a self-serious ex-confederate colonel, the other one a jolly scoundrel – in the Franco-Mexican War, where they are hired to escort a countess and soon get embroiled in a series of cunning ploys, as everybody double-crosses each other to get their hands on a gold shipment. Vera Cruz is set in the 1860s, so technically it’s not a Zapata Western – if anything, it’s a Juárez Western – but it does feel like a natural precursor to The Professionals (where Burt Lancaster plays a much less cynical character than here…).

32. Two Mules for Sister Sara (1970)

32. Two Mules for Sister Sara (1970)

With a similar setting and comedic spirit, Two Mules for Sister Sara is in many ways the perfect companion piece to Vera Cruz. Rather than a rascally bandit, though, this time around the chivalrous ex-soldier (here played by Clint Eastwood in lieu of Gary Cooper) acts as the straight man in a bickering partnership with a revolutionary nun (played by the reliably funny Shirley MacLaine).

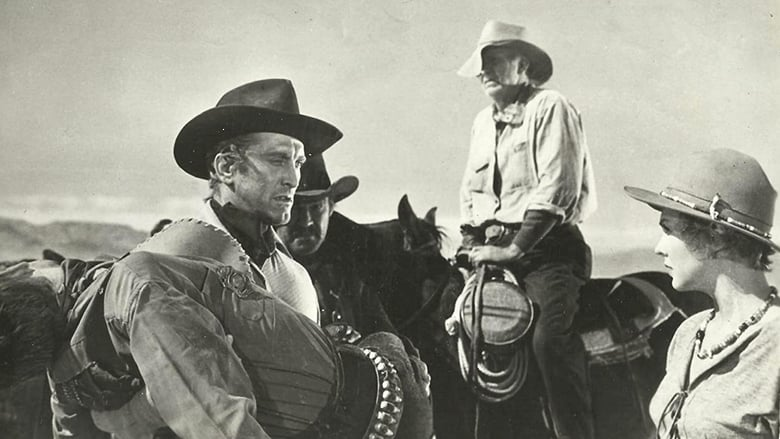

33. Along the Great Divide (1951)

33. Along the Great Divide (1951)

Kirk Douglas as a federal marshal who saves a man (the always entertaining Walter Brennan) from lynching and tries to take him to trial while getting chased across the desert by vengeful ranchers. Come for the amazing cinematography and a nice supporting part by Virginia Mayo (as Brennan’s feisty daughter), stay for the provocative sense of frustration with different forms of justice.

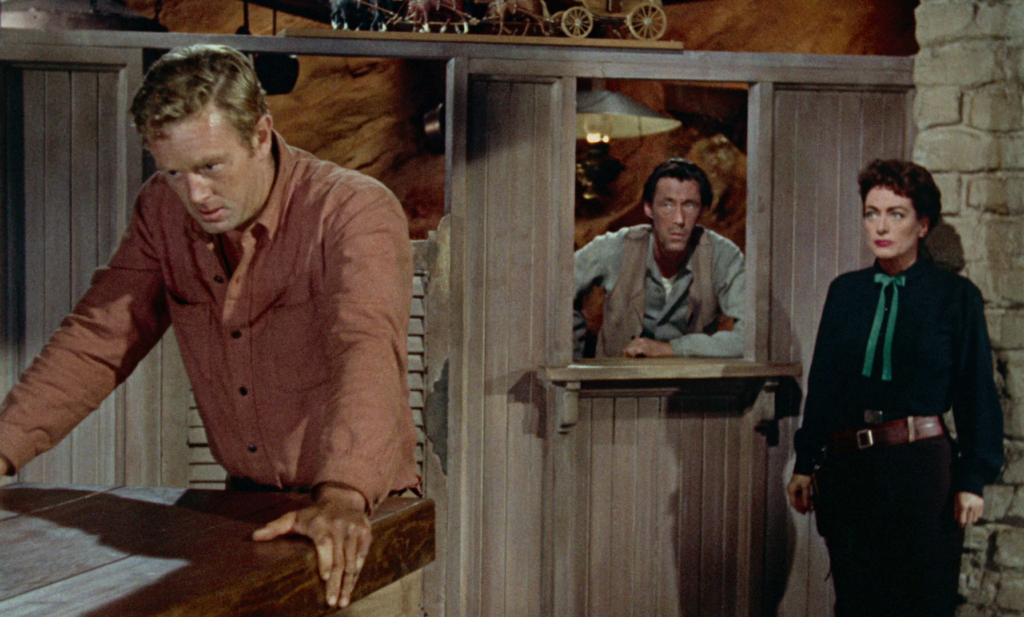

34. Johnny Guitar (1954)

34. Johnny Guitar (1954)

A mysterious muscular rider who carries a guitar but no visible guns, Johnny may lend his name to the title, but the main star of this unapologetically artificial and theatrical opus is Joan Crawford’s Vienna, the kickass owner of a saloon/casino in the outskirts of a New Mexico town waiting to profit from the upcoming railroad while facing off the town’s reactionary mob (yep, it’s another HUAC allegory). Working with a script chockful of nifty lines and pushing each scene’s pathos to the brink, director Nicholas Ray seems less interested in the actual story than in blowing up genre aesthetics through flamboyant color and sexual undertones (he later did the same for gangster pics in Party Girl).

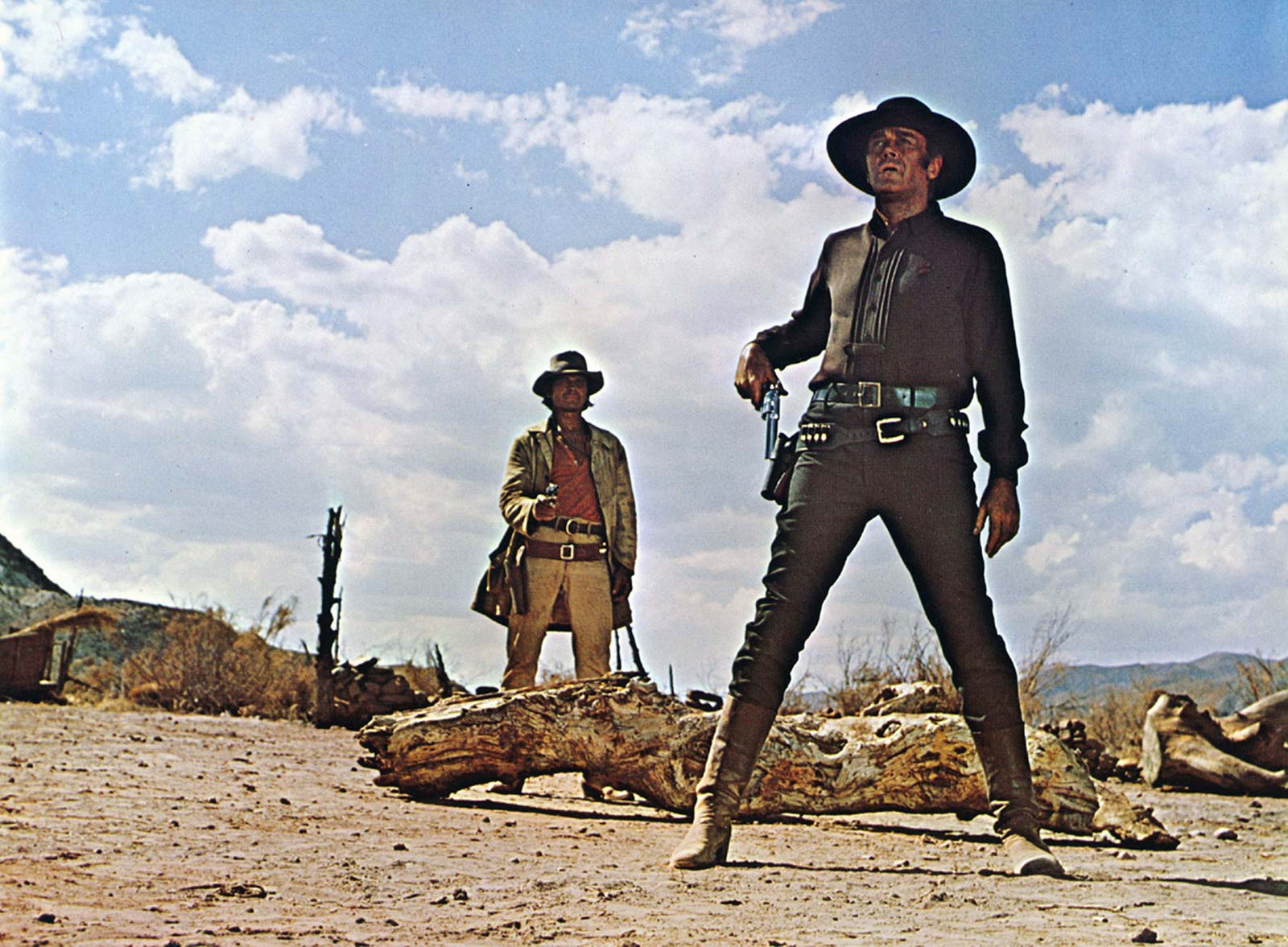

35. The Mercenary, aka A Professional Gun (1968)

35. The Mercenary, aka A Professional Gun (1968)

A Mexican rebel and a couple of foreign guns-for-hire – a taciturn Pole and a campy American – enter into a game of temporary alliances and deadly betrayals in yet another stylized clash between romantic ideals and callous capitalism. If A Bullet for the General inaugurated the Zapata Western and Duck, You Sucker! mocked its idealism, The Mercenary exploited this subgenre’s leftist politics as a vehicle to heighten the impact of Corbucci’s trademark brand of garish, visceral mayhem…

36. Last Train from Gun Hill (1959)

36. Last Train from Gun Hill (1959)

Once again, Kirk Douglas finds himself trying to bring someone to justice against the will of everyone around him, with lethal results… For once, the final showdown feels much less cathartic than outright tragic (the tragedy is set up from early on – after the despicable act in the beginning of the film, there is no turning back).

37. Yellow Sky (1948)

37. Yellow Sky (1948)

After a mean trek through the sun-soaked Death Valley desert, a gang of bank robbers stumbles its way into a ghost town inhabited only by a fierce young woman and her grandfather… and soon things get even grimmer. The style is particularly noirish in this one (not least because of cinematographer Joe MacDonald and a sneering role by Richard Widmark), although the story apparently takes its inspiration from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, all of which makes Yellow Sky stand out as quite an original western experience. (It helps if you disregard the annoyingly silly coda.)

38. Death Rides a Horse (1967)

38. Death Rides a Horse (1967)

Practically all of the movies on this list deal with (at the very least the threat of) murder and rape, but Giulio Petroni still manages to deliver the most disturbing opening of the lot, deploying horror film techniques to depict the slaughter that the hero witnesses as a child and which determines the rest of his life. And yet, what follows is quite a playful, pulpy ride, with John Phillip Law’s marksman tracking down his family’s killers based on visual clues from his memories, under the reluctant tutorship of Lee Van Cleef’s roguish ex-con. Scholars have pointed out spaghetti westerns’ apparent preference for fetishized objects and expressive external actions over thematic depth and complex internal emotions (compared to old Hollywood oaters, that is), possibly reflecting the burgeoning consumerism in 1960s’ Italian society. Death Rides a Horse, however, clearly shows how objects can be imbued with both cinematic coolness and a deeper significance as channels of revenge, redemption, and trauma.

39. Seven Men from Now (1956)

39. Seven Men from Now (1956)

The first movie in Boetticher’s, Kennedy’s and Scott’s Ranown Cycle is already a terrific display of what this trio can accomplish with their economical approach to narrative, crafting a lean, brisk tale about a lone rider who gets slightly sidetracked from his mission of vengeance when he takes it upon himself to secure the safety of a young married couple on their way west to California. Like in many movies from the ‘50s, the core subtext concerns the tension between different versions of masculinity (yes, contrary to what many critics suggest, this was not a new subject introduced in the 21st century by Brokeback Mountain and The Power of the Dog).

40. The Treasure of Sierra Madre (1948)

40. The Treasure of Sierra Madre (1948)

A deadbeat, seduced by an old miner’s talk of prospecting, goes on an expedition in the mountains that steadily corrupts his mind and soul. Although this angry parable about gold’s morally corrosive power has a few rough spots, it’s more than saved by John Huston’s expressionistic direction, not to mention the magnetic performances of a deranged Humphrey Bogart and a grizzled Walter Huston (no wonder the film has had such a lasting cultural impact, still echoing as recently as Spike Lee’s Da 5 Bloods and David Lapham’s Stray Bullets: Sunshine and Roses #11). I hesitated about including it because, even though The Treasure of Sierra Madre is nominally set in 1925 Mexico, at first it looks closer to the present (of the 1940s), but once the wilderness takes over, there are enough continuities with the familiar motifs of horse-riding bandits and greedy, gun-wielding bastards…

41. Sabata (1969)

41. Sabata (1969)

With a catchy score and a relentless pace, this is yet another Italian gem starring Lee Van Cleef as a drifter in an ultra-twisty plot. Remarkably, the gimmicky weapons, the colorful supporting cast, and the endless profusion of double- and triple-crosses give Sabata an outstanding comedic flair, but it never fully strays into all-out goofiness.

42. And God Said to Cain (1970)

42. And God Said to Cain (1970)

What if you shot an entire western like a gothic horror movie? There isn’t anything necessarily supernatural going on in And God Said to Cain (unless you consider Klaus Kinki’s protagonist to be a ghost, in which case the opening labor camp would be hell), but there are enough pipe organs in the soundtrack and curtains flapping in the nightly wind to make this one a spooky genre hybrid.

43. McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971)

43. McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971)

And what if Robert Altman did a western? Predictably, the result is revisionist and naturalistic, but it’s also achingly melancholic (not least because of Leonard Cohen’s spellbinding songs). The film revolves around the titular entrepreneur and whorehouse madam, but their relationship feels like a mere piece in a grander story about the development of a mining town under harsh conditions. Many movies are on this list because they gratifyingly nail – or even elevate – the genre’s formulas, but others actually approach the material with a distinct sensibility that’s unlike anything else out there. McCabe & Mrs. Miller definitely belongs to the latter group.

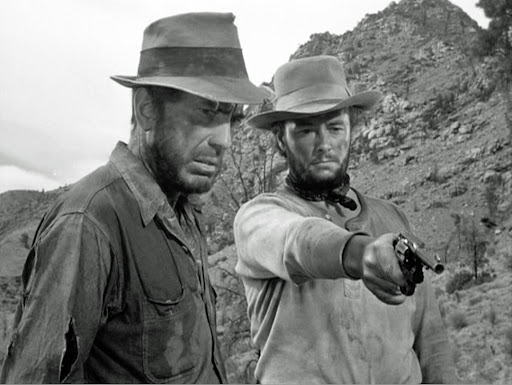

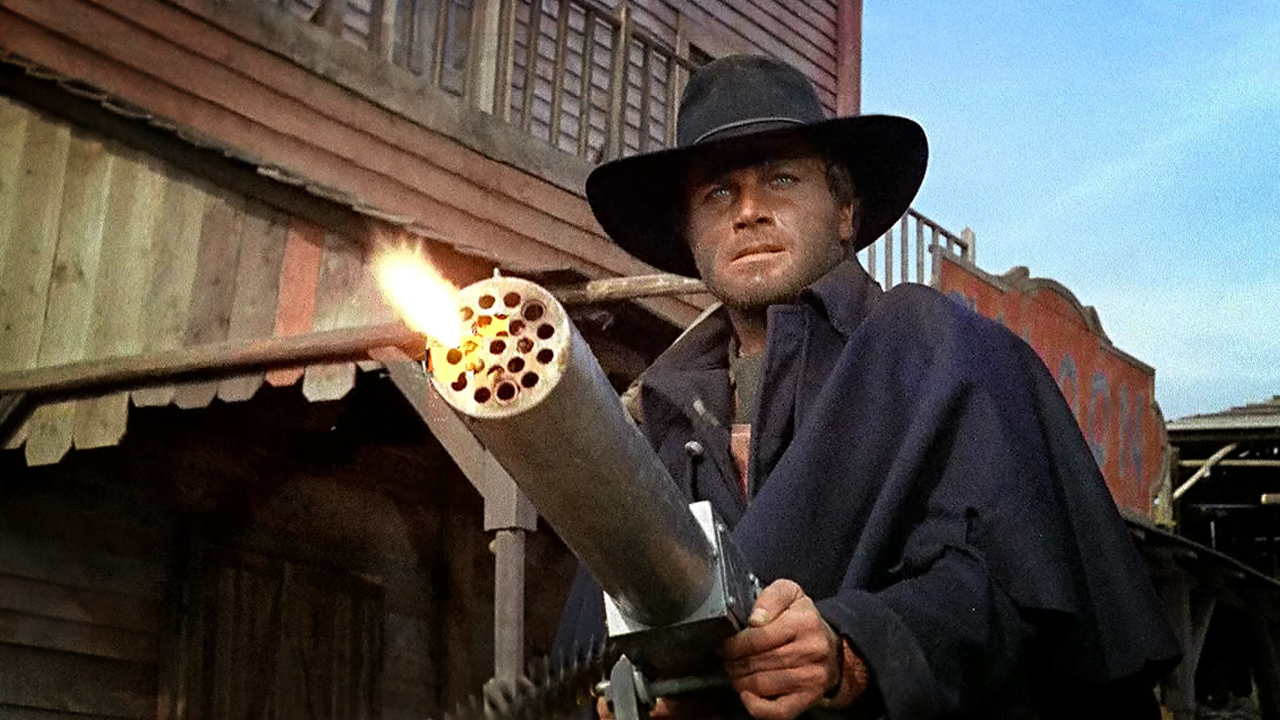

44. A Stranger in Town, aka For a Dollar in the Teeth (1967)

44. A Stranger in Town, aka For a Dollar in the Teeth (1967)

Many spaghetti westerns were basically unofficial remakes/rip-offs of For a Fistful of Dollars, usually building on its generic set-up while exaggerating its stylistic flourishes. For my money, A Stranger in Town is the finest example of a B-movie remixing the same ingredients to craft something that feels like an eerie nightmare you’d have after watching Leone’s film. As derivative as it looks, I’d say Stranger manages to find its own voice, but maybe ‘voice’ isn’t the best metaphor here: even for Italian standards, this has got to be one of the most laconic westerns ever, with only a fistful of scenes with dialogue (which further intensifies the overall mesmerizing allure). Plus, it finishes with, not one, but two fun punchlines.

45. Django (1966)

45. Django (1966)

The most renowned of the post-Fistful of Dollars knock-offs, by far, is Django, which itself inspired over 30 titles (although the overwhelming majority bear little connection to the original movie). Yes, it’s another variation of the Yojimbo formula, but this one managed to stand out not only by tripling the level of sadism, but also by filling the screen with all sorts of baroque touches, most memorably the protagonist in a muddy Union uniform dragging a coffin behind him before facing a racist gang wearing bright-red Ku Klux Klan hoods…

46. Bone Tomahawk (2015)

46. Bone Tomahawk (2015)

Just one more western/horror hybrid – this one with a fair amount of black comedy thrown in for good measure… With a strong cast spearheaded by a gruffy Kurt Russell, Bone Tomahawk succeeds on all levels. As a western, it looks fantastic (with a sepia-ish filter that evokes our mediated memory of the period) and the cackling dialogue is rich with quaint turns-of-phrase. As a gory horror flick, it dives deep into the scary pit of cannibalistic savagery, with a small posse searching for people abducted by a tribe of animalistic, cave-dwelling troglodytes. The movie awkwardly tries to sidestep the obvious racist implications of this premise (including through a hilariously ham-fisted scene where a Native-American expert explains that troglodytes have nothing to do with so-called Indians, even though the prejudiced white folks wouldn’t be able to distinguish them), but I actually think it works better if you just throw away any pretention of historical accuracy altogether: given the literary affectation of the whole thing, I see this story not as a supposedly realistic depiction of the past, but as a haunting take on the sort of monstrous fantasies imagined by the settlers at the time.

47. Have a Good Funeral, My Friend… Sartana Will Pay (1970)

47. Have a Good Funeral, My Friend… Sartana Will Pay (1970)

My favorite instalment in the very droll Sartana series – about the eponymous gunfighter/gambler/illusionist – strikes a balance between a neat mystery plot and bursts of gonzo comedy, with an anything-goes attitude close to many of the comics I usually discuss in this blog. For instance, the title refers to the fact that the hero keeps paying for the funerals of the (many) people he kills throughout the film.

48. My Name Is Nobody (1973)

48. My Name Is Nobody (1973)

A particularly meta western, in which the fan of an old gunslinger (who just wants to retire) tries to get his idol to fight one last glorious battle, for legend’s sake. Besides the self-reflexive premise, there is the fact that the latter is played by Henry Fonda (whose genre credits stretch as far back as the 1930s) and the former by Terence Hill (the main face of the then-latest trend of slapstick westerns). Suitably, Tonino Valerii’s direction (with second unit work by Sergio Leone) keeps oscillating between tense, deliberately paced classic set pieces and spirited detours into lowbrow comedy. The result is uneven, but often delightful.

49. Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973)

49. Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973)

Sam Peckinpah’s magnificent ode to the erosive passage of time follows an ageing Pat Garrett, who gets hired to bring down his old pal Billy the Kid. Like in McCabe and Mrs. Miller, the leisured narrative is carried by mournful music, now courtesy of Bob Dylan (who also plays a peripheral role in the film).

50. The Gold Rush (1925)

50. The Gold Rush (1925)

Although it’s not an obvious western, The Gold Rush is set in late 19th-century America (in the Klondike Gold Rush) and it involves deadly fights, shooting, a wanted outlaw in the wilderness, and a sense of rudimentary civilization in the making, so it totally counts! Indeed, like many of the entries earlier in the list, this one is full of violence and cruelty and men backstabbing each other for gold… Yes, it’s also a hilarious slapstick comedy, but so many of the laughs derive from extreme deprivation (sickness, hunger, cold, madness, even cannibalism) that you can almost make a case for this Charlie Chaplin masterpiece as a forerunner for Corbucci’s and Tarantino’s later brands of bleak humor.