Gotham Calling’s 400th post!

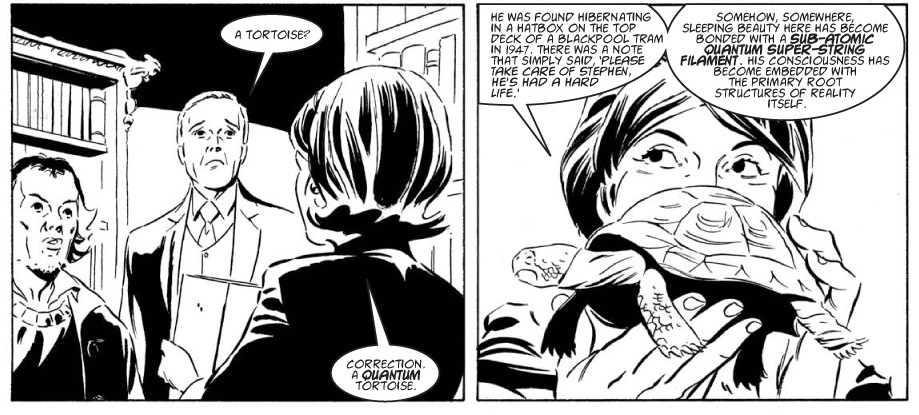

This is the kind of benchmark I usually celebrate by spotlighting oddball members of Batman’s rogues gallery who don’t get enough love. While the Dark Knight has some of the most popular rogues out there, Gotham’s very tendency to keep spitting out new demented criminals is a big part of the franchise’s mystique – and one of its main sources of humor. It means that you can even pull off homages to this world without riffing on specific characters, since readers can recognize the *type* of villains that could show up in Batman tales (for example, Big Bang Comics (v2) #11 does a wonderful job of evoking this feel). Moreover, those throwaway foes, with their damaged psychology underneath silly, referential identities, tend to come off as particularly pathetic underdogs, so a part of me cannot help but root for them as they punch way above their weight by going up against the Caped Crusader.

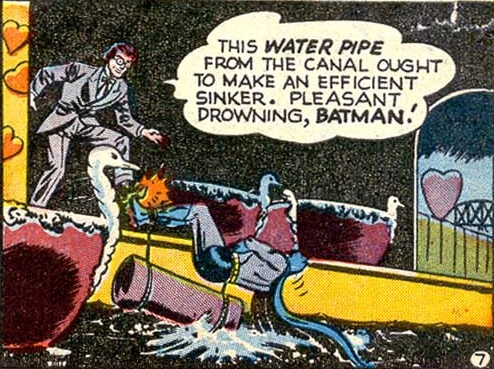

For instance, take the Pied Piper of Peril, who uses pipes to commit crimes:

Detective Comics #143

Detective Comics #143

The Pied Piper made his first – and, I believe, only – appearance in Detective Comics #143 (cover-dated January 1949), by the fruitful creative team of writer Bill Finger, penciller Jim Mooney (ghosting for Bob Kane), and inker Charles Paris. What raises the character above a mere thief with a visually interesting technique is the committed embrace of his gimmick’s semantic potential. In other words, what makes him truly eccentric isn’t that he robs a bank with weaponized corncob pipes, as shown above, but that he uses all sorts of pipes – from exhaust pipes to bagpipes – to commit different crimes related to the victims’ names…

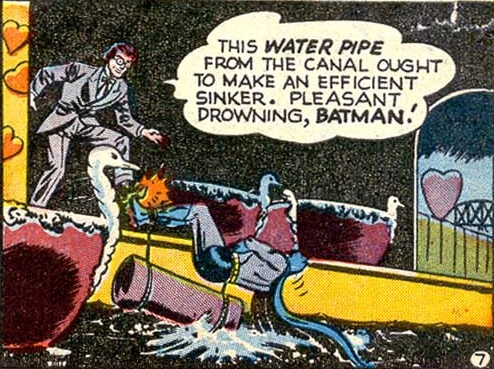

It’s the kind of comic where, if you take a step back, you can just picture Finger jolting down every idea he could come up with related to one specific object (or one word with multiple uses) and then building the whole script around it. Every standard Batman trope (from Gotham City’s gaudy architecture to the puns in the Dynamic Duo’s dialogue) is then adjusted according to a single motif – in this instance, pipes. So, for example, here is the obligatory deathtrap:

Detective Comics #143

Detective Comics #143

This storytelling strategy can produce pretty entertaining comics, which often come out as either quite cohesive or hilariously forced. The ensuing villains tend to run out of steam pretty quickly, though, since they amount to little more than a superficial word-association exercise that has already been fully explored.

That said, from an in-story perspective, because they only show up once, characters like the Pied Piper of Peril come across like criminal hobbyists having fun rather than like full-blown psychopaths, which is a nice change of pace in the daily exploits of the Dark Knight. Hell, they end up seeming relatively harmless, to the point where you can almost see Batman actually letting them get away, just out of respect for the fact that they clearly put a lot of effort into the whole thing… Regardless, the fact that these kooky crooks don’t reappear can serve as a helpful counterpoint to the troubling implications in the genre’s intrinsic discourse about recidivism (admirably spoofed in Wonder Twins #2).

A similar case of working an entire story out of a single concept could also be found in the previous year, in ‘The Human Key!’ (Detective Comics #132, February 1948), by the same creative team:

Detective Comics #132

Detective Comics #132

(I absolutely love the impractical costume!)

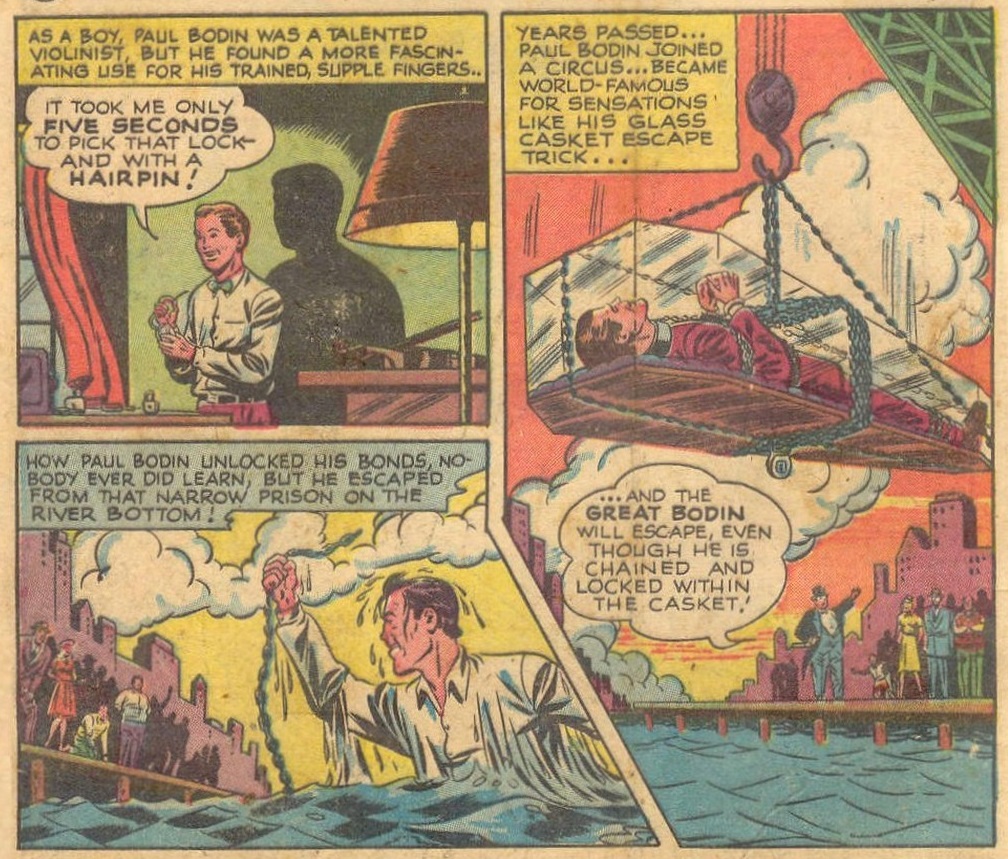

In this quintessential Batman tale, the Dynamic Duo faces a criminal version of Harry Houdini in the form of a master locksmith who can break into any safe (and, presumably, out of every prison, although, given the story’s resolution, it makes sense that we never saw further crime sprees by the Human Key).

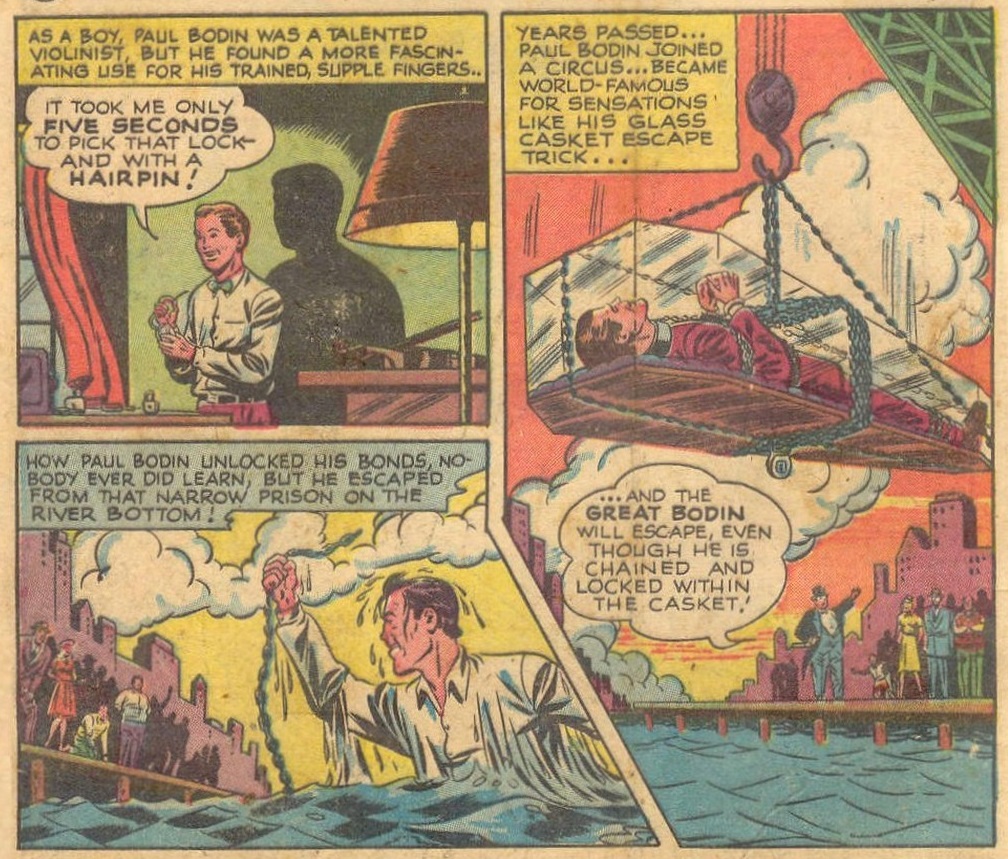

In a typical approach to characterization, the villain’s obsession harkens back to his childhood, giving a sense of inescapable destiny to his personality, even if – for once – the Human Key’s origin does not involve any serious trauma, but merely the passionate use of a personal skill…

Detective Comics #132

Detective Comics #132

Once again, Bill Finger stretches the meaning of the villain’s theme through whimsical games of polysemy. While the Human Key’s name and major M.O. clearly refer to his expertise in unlocking physical locks, that doesn’t prevent this brilliant safecracker from providing outrageously convoluted clues that draw on other uses of the term ‘key’ – in particular, he tips off the Dynamic Duo about his next job by whistling in a specific musical key!

Likewise, we get another deathtrap linked to the foe’s chosen motif. The result is an epitome of one of my favorite type of scenes, with the Caped Crusader using his intelligence, imagination, and scientific knowledge to figure out an escape:

Detective Comics #132

Detective Comics #132

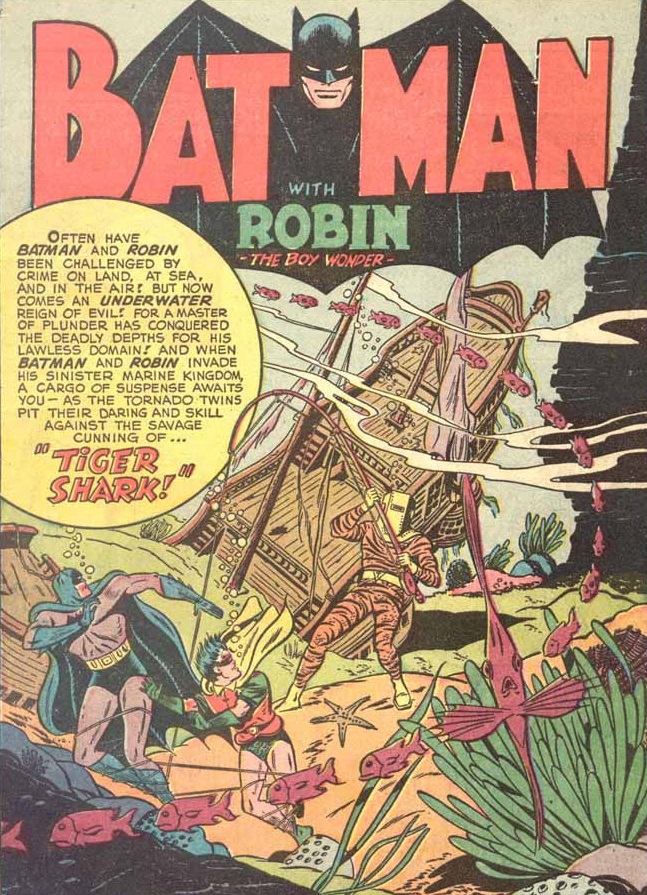

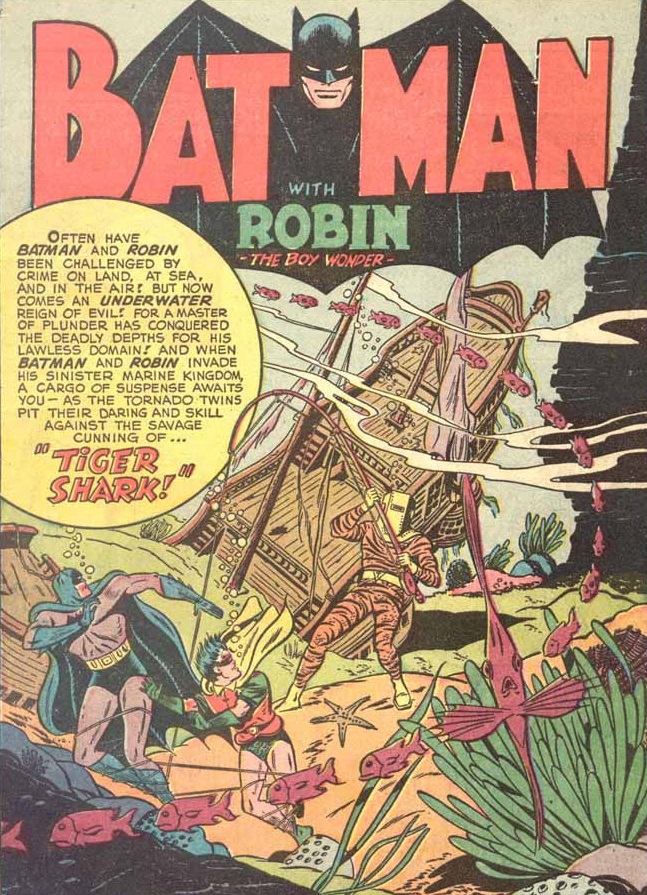

Just one more example from the Golden Age: ‘Tiger Shark!’ (Detective Comics #147, May 1949), where the titular villain is a subaquatic thief equipped with marine gadgets and knowledge. This tale (by an unknown writer) doesn’t seem to have sprung up from wordplay, but rather from the alluring notion of pitting the Dark Knight against a modern-day pirate with a fancy submarine and scuba-diving henchmen.

Gotham being Gotham, the crook has to have a preposterous costume… This time around the design is by Dick Sprang (also inked by Charles Paris). In a delightfully odd choice, either Sprang or whoever colored the original comic chose to base the villain’s look, not on an actual tiger shark, but on a literal extrapolation from part of his name: the costume has black stripes over an orange pattern, like the fur of a (non-shark) tiger:

Detective Comics #147

Detective Comics #147

(It’s also a neatly designed splash page… I particularly enjoy the fish in the bottom right corner, who seems to be staring at the readers, mirroring their surprised look.)

The outfit may feel especially weird if you consider that, unlike tigers, killer sharks have become a huge part of pop culture, although, in its defense, this comic came out almost thirty years before Jaws. Plus, the truth is that such a cool design can take you a long way… ‘Tiger Shark!’ is fine, but as a story it’s less amusing than either ‘The Human Key!’ or ‘The Pied Piper of Peril!’ Nevertheless, Tiger Shark became comparatively more iconic than those other villains, earning a few memorable cameos in the 2008 cartoon show Batman: The Brave and the Bold.

Speaking of the 21st century trend of bringing back goofy creations from the Caped Crusader’s earlier decades: the criminal illusionist Zelda the Great moved in the opposite direction from Tiger Shark, starting off on the small screen and eventually finding her way to the printed page. She made her debut in the 1966 Batman TV series, on the episodes ‘Zelda the Great’ and ‘A Death Worse Than Fate’ (a two-parter saga, as per the show’s formula). Despite the usual mix of spectacular art direction and offbeat comedy (which you can also find in the series’ awesome trading cards), those episodes weren’t necessarily among the first season’s highest points, even if they later earned their place in history by featuring the opening line of White Zombie’s ‘Cosmic Monsters Inc.’

Zelda’s initial gimmick was pretty specific: she robbed one hundred thousand dollars from a bank every year, on April 1st. It turned out that even though she was a world-famous escape artist, Zelda secretly bought her act’s traps and escape solutions from the self-proclaimed Albanian genius Eivol Ekdol, for $100,000 apiece. When Batman planted a fake news item in the Gotham City Times claiming the money from her latest robbery was counterfeit, though, she happily switched tactics, kidnapping Dick Grayson’s aunt Harriet and suspending her in a straitjacket over a pool of flaming oil while waiting for the $100,000 ransom…

‘Zelda the Great’

‘Zelda the Great’

In ‘A Death Worse Than Fate,’ we found out that not even Eivol Ekdol knew how to escape from his latest trap, so he and Zelda lured the Caped Crusader into it in the hopes that Batman’s inevitable escape would show them how the trap could be used on the stage… As motivations for crime go, this one was pretty bonkers, but also perfectly in tune with the show’s campy attitude. That attitude, by the way, reached a new height during a priceless sequence in which Commissioner Gordon, speaking to Zelda on a live television broadcast, explained to her the money from the original robbery wasn’t counterfeit after all while holding a one-sentence statement from the editor of the Gotham City Times – ‘Look, it’s signed and notarized!’ (By the way, did I mention that in this reality Bruce Wayne was the director of the First National Bank of Gotham City?)

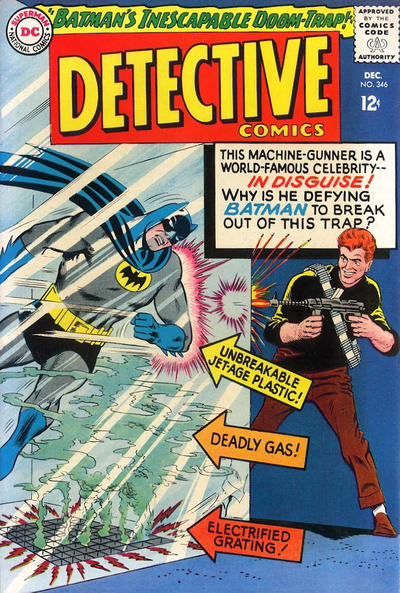

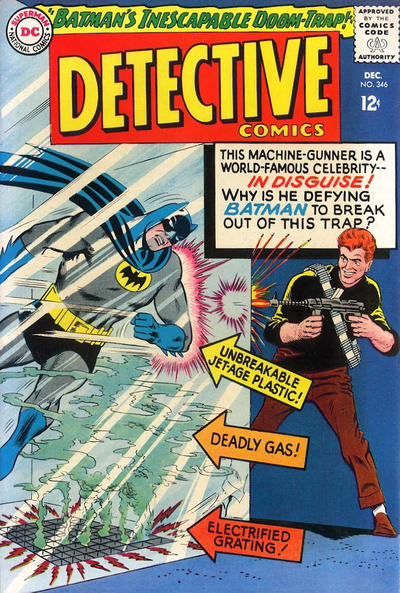

Apart from the kidnapping subplot, the episodes’ overall story was actually based on ‘Batman’s Inescapable Doom-Trap!’ (Detective Comics #346, December 1965), by John Broome, Sheldon Moldoff, and Joe Giella.

Zelda the Great, then, was a gender-swapped version of that comic’s escape-artist-turned-thief, Carnado, but she came off as much cleverer, seeing through the Dynamic Duo’s early ruse (she even broke the fourth wall to brag about it to the audience) and nonchalantly outsmarting them in the first part of the story. Moreover, you get the feeling that it wasn’t just a moral compass that led her to spare Batman’s life in the climactic ambush, especially as the previous episode had already established the Dark Knight’s powerful sex appeal (in the comic, Batman didn’t need any aid: he figured out where the shooters were by paying attention to the way Carnado’s eyes moved). It helped that guest star Anne Baxter imbued her performance with so much charisma and ill-disguised titillation – in my head-canon, she’s playing the same character as in All About Eve, whose career has taken a zany turn since we last saw her because entertainment is such a ruthless business (the point of that movie, after all).

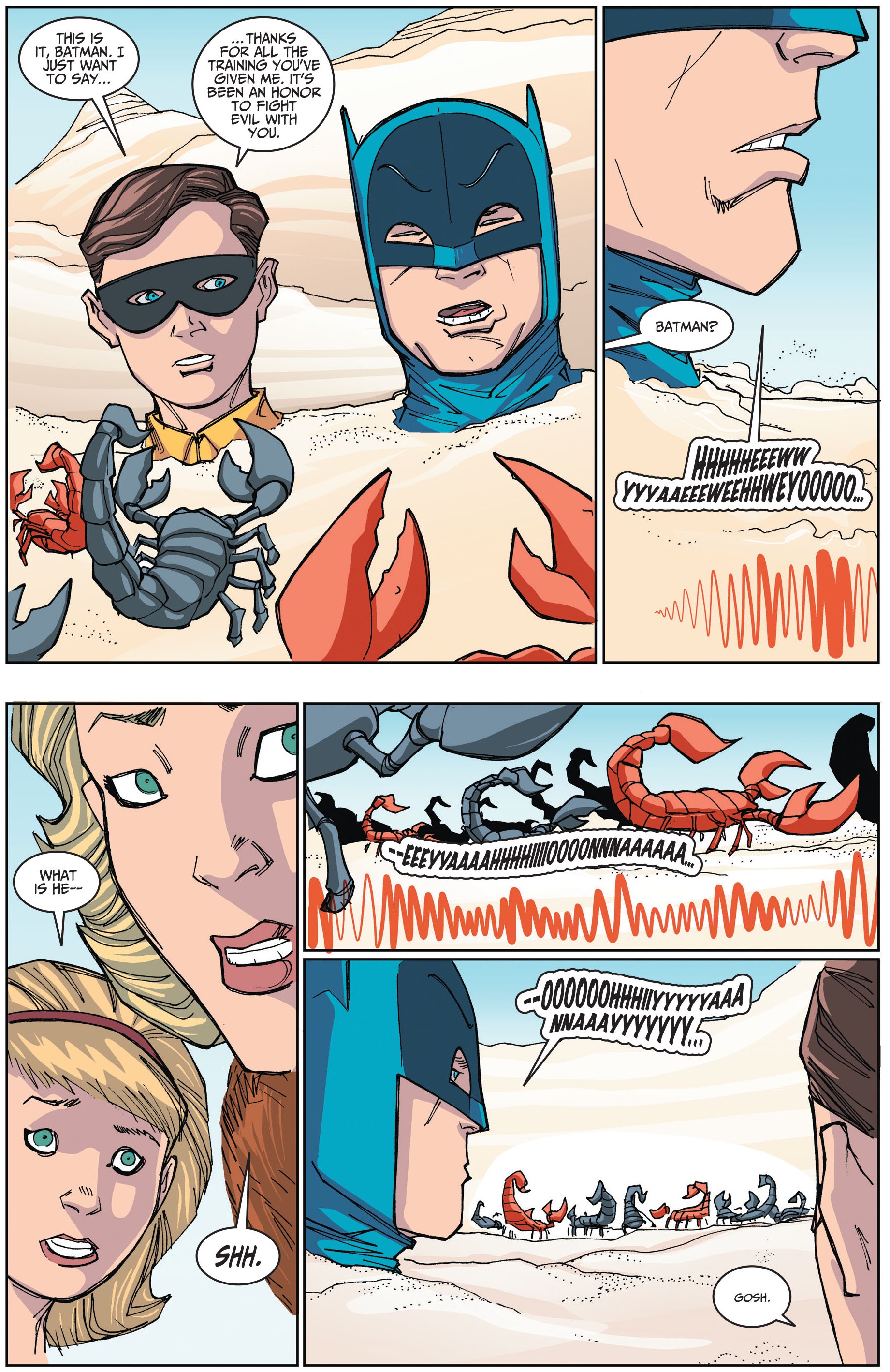

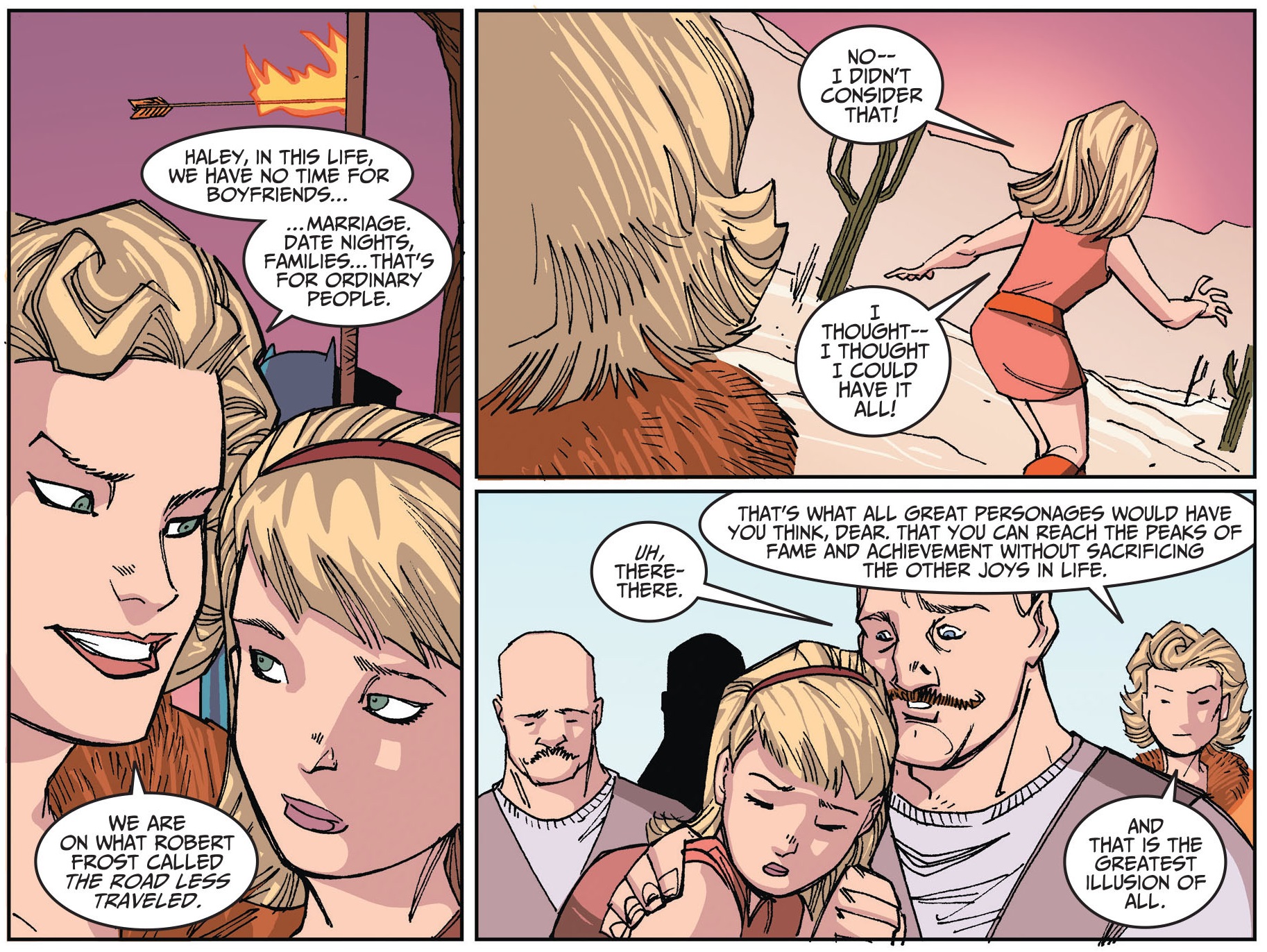

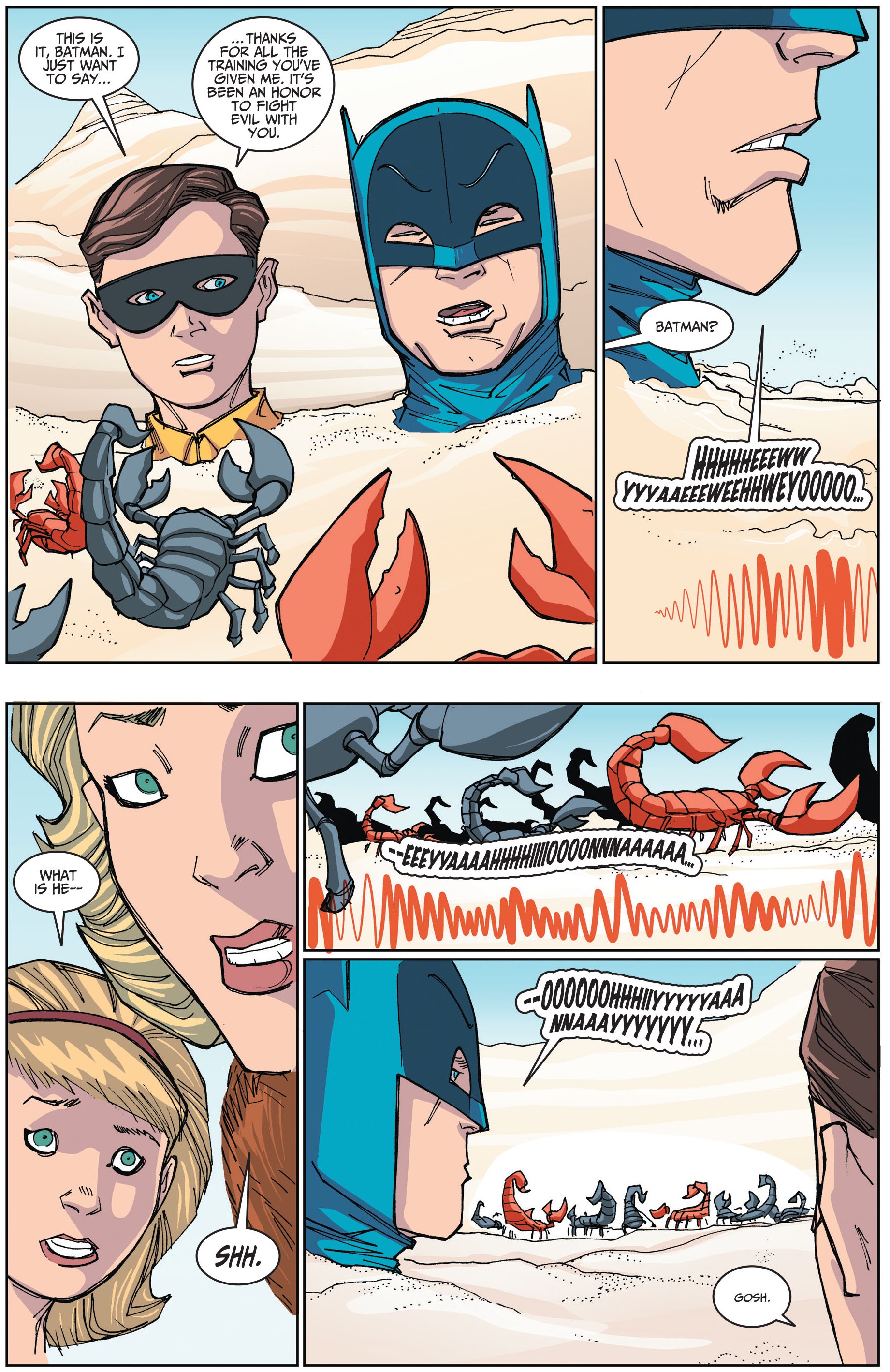

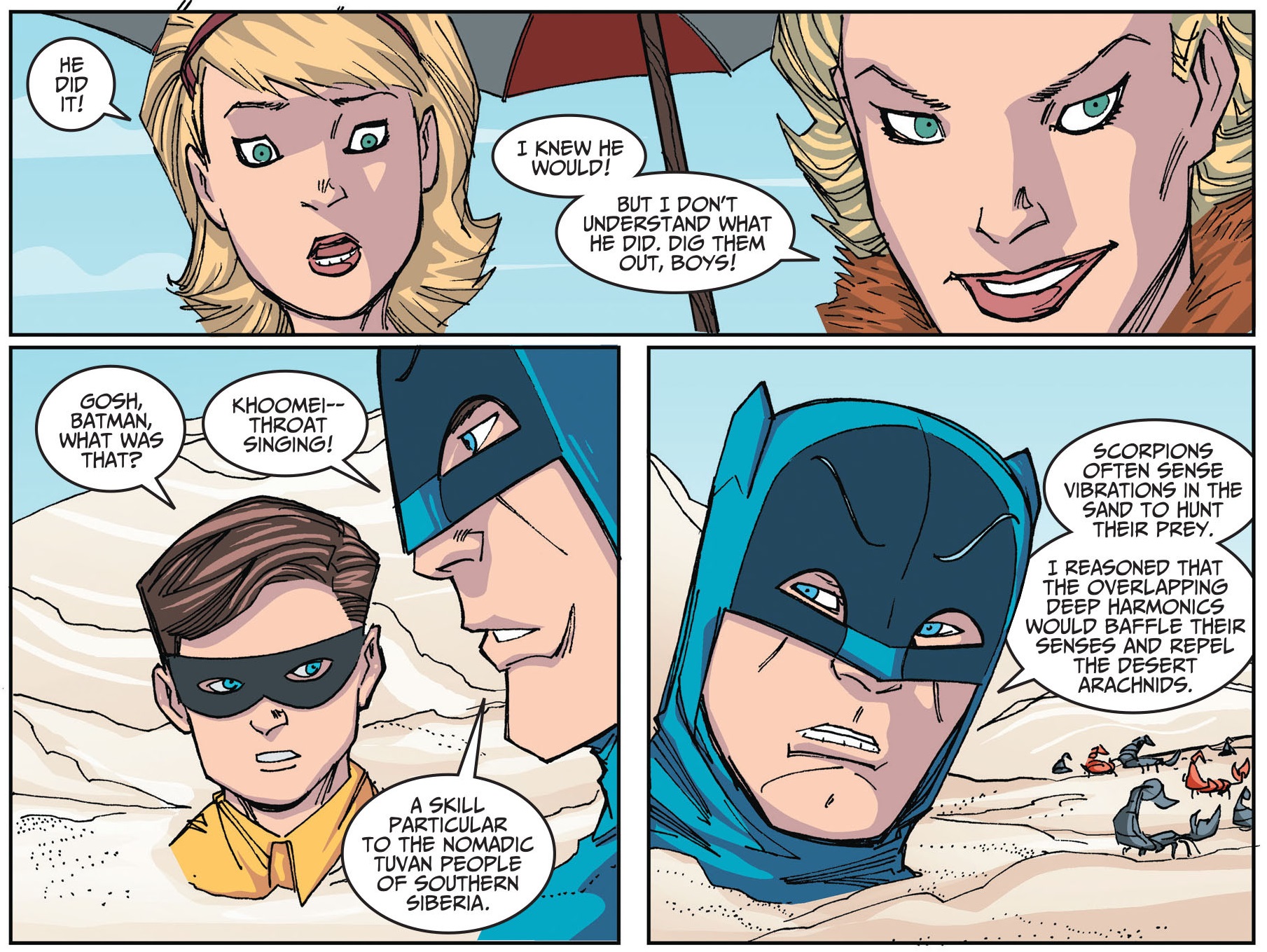

While the ridiculously named Carnado was never heard of again, Zelda the Great reappeared in 2014, on the pages of Batman ’66, a comic book spin-off of the sixties’ show (created almost fifty years later, because that’s nostalgia for you). In ‘Zelda’s Great Escape’ – written by Jeff Parker, illustrated by Craig Rousseau, and colored by Tony Aviña – we see this villain has turned the previous story’s premise into a whole modus operandi, repeatedly trapping the Dynamic Duo in order to copy their escapes in her stage act…

Batman ’66 #9

Batman ’66 #9

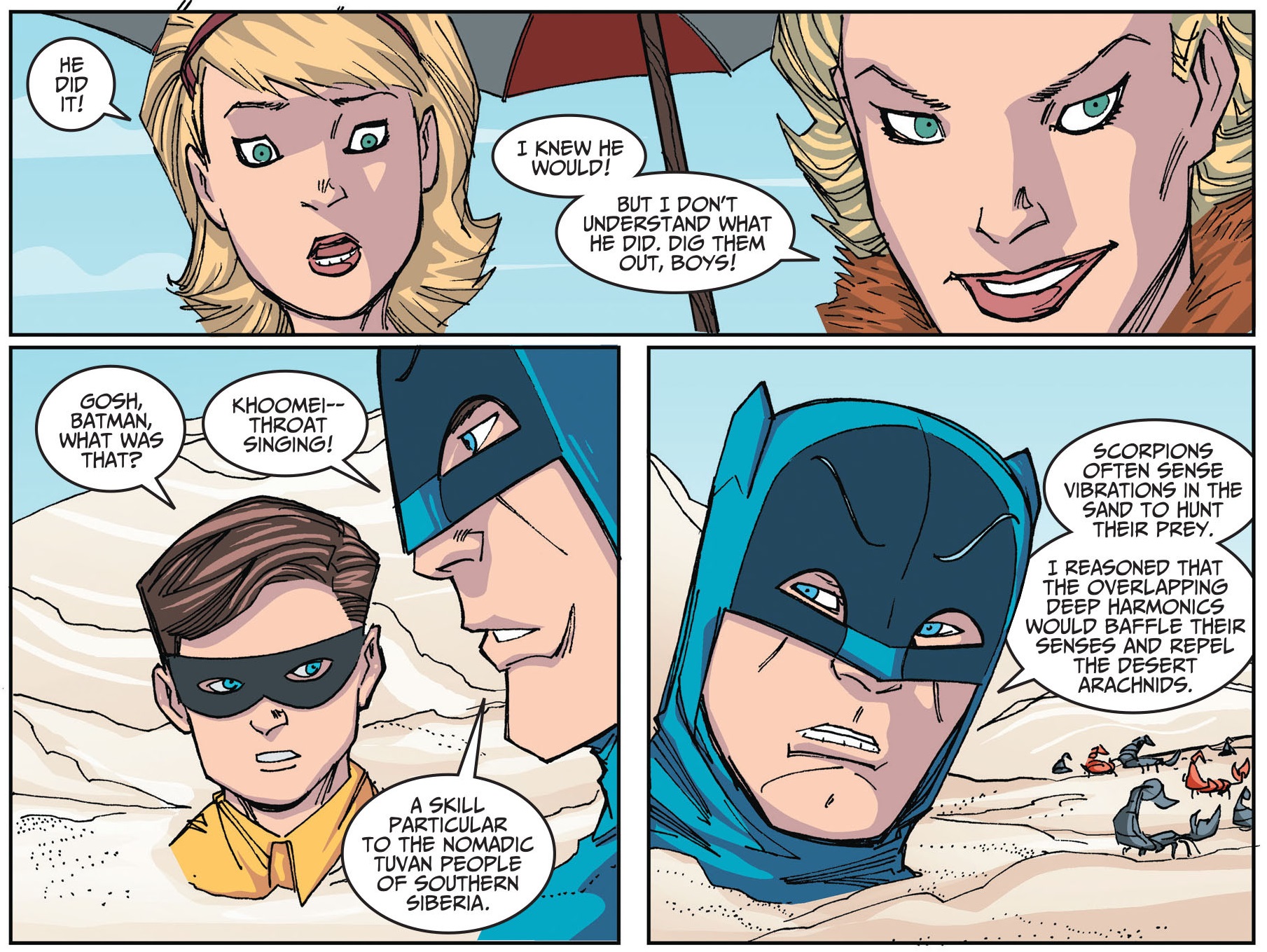

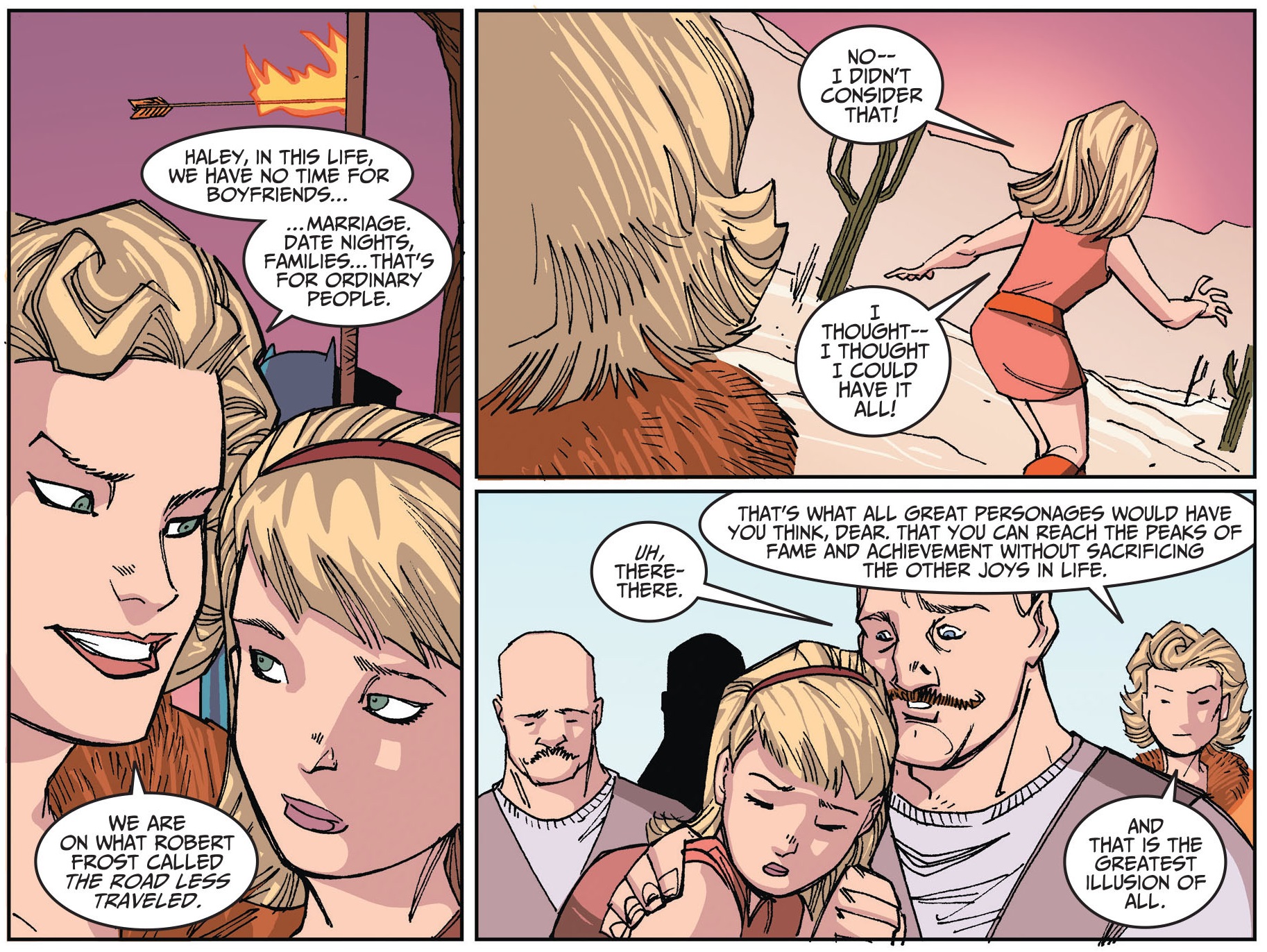

While the main joke is Zelda’s explicit obsession with showmanship (as opposed to its implicit status in the performative crimes and showy deathtraps of Batman’s usual rogues), what elevates this tale is Jeff Parker’s decision to actually give Zelda the Great a philosophical justification for her willingness to go to such extremes in the quest for fame and glory… And because Dick Grayson’s date, Haley, seems persuaded by Zelda’s warped worldview, the villain actually ends up striking quite a blow against the Teen Wonder, without even realizing it!

Batman ’66 #9

Batman ’66 #9

Don’t get me wrong: I love scary villains. In fact, I think Batman has generally gained a lot from drawing on horror imagery, whether it’s David Lapham riffing on Invasion of the Body Snatchers in his ‘City of Crime’ saga, Kelley Jones filling every single one of his pages with a parade of grotesqueries, or Christopher Nolan shooting the docks’ scene in Batman Begins from the crooks’ terrified point of view, as if it was a slasher movie. However, there’s more than enough room in my Gotham for the sort of colorful, flamboyant escapades that you get with characters like Zelda the Great.

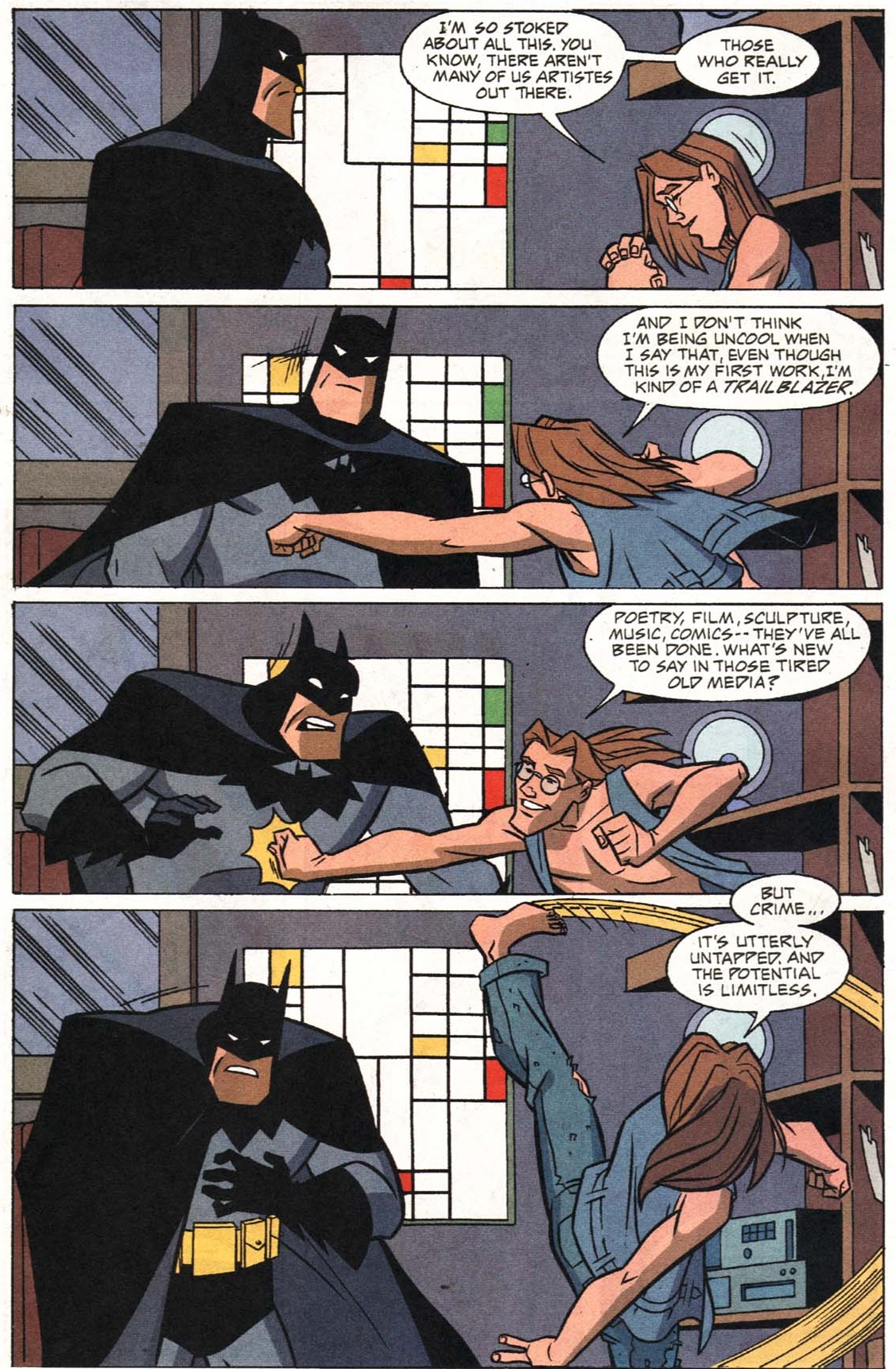

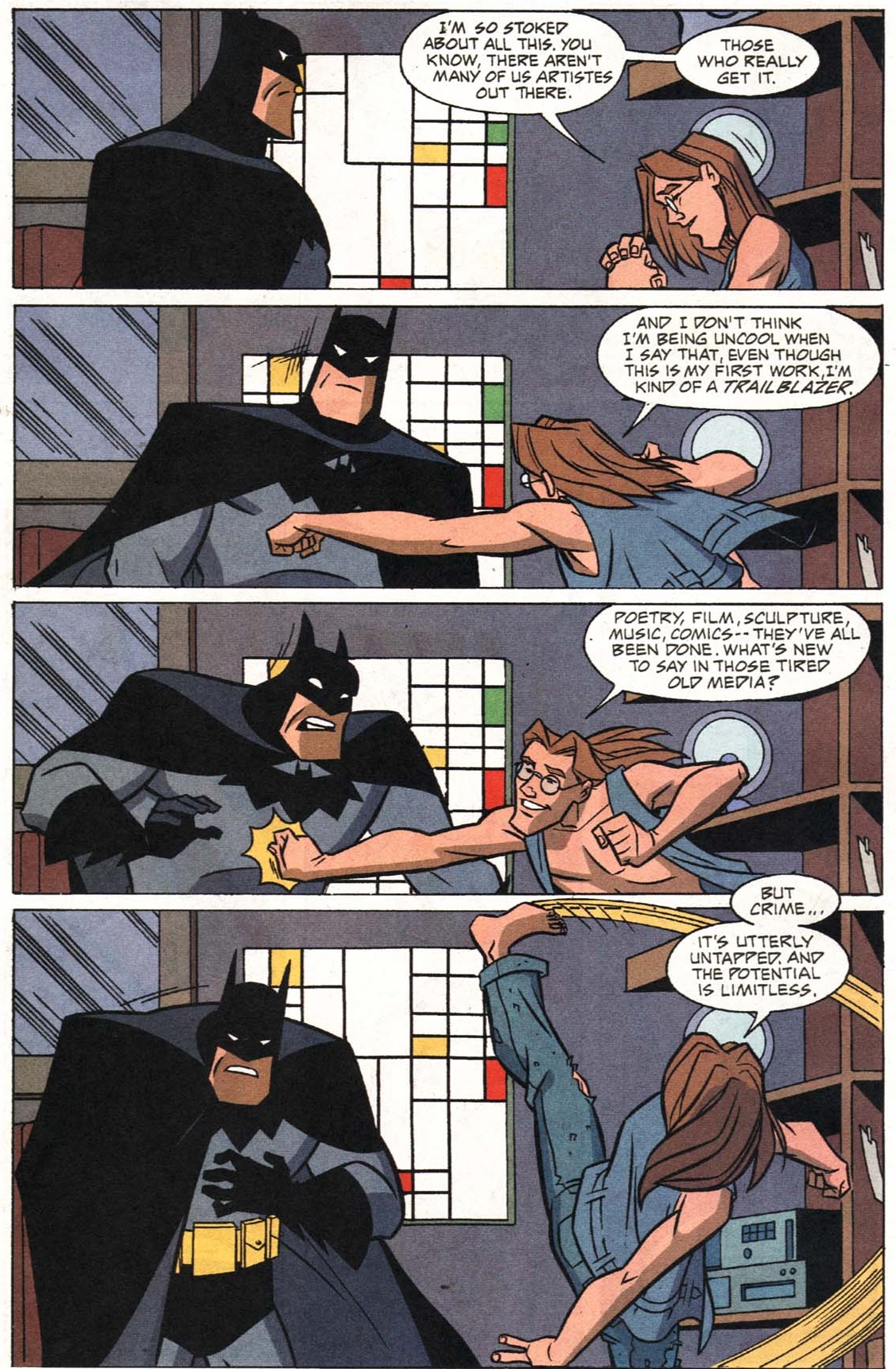

For instance, another rarely seen villain I really like – and who also straddled the line between spectacle and delinquency – was a guy called Kim, who made his debut in ‘The Art of the Steal’ (Gotham Adventures #49, June 2002). That issue was part of the underrated – because bafflingly uncollected – run by Scott Peterson, Tim Levins, Terry Beatty, and Lee Loughridge, who in the early 2000s put out a phenomenal string of one-and-done stories featuring fun mysteries, boisterous action scenes, slick visual storytelling, and some of best takes on the Caped Crusader and his world. Although Gotham Adventures was mostly focused on standard gangsters or on familiar rogues, this creative team came up with a new villain, one who approached crime, not as a means, but as an end in itself – more specifically, Kim understood crime as a possible art form!

Gotham Adventures #49

Gotham Adventures #49

It was a particularly conceptual understanding of art, which owed more to cerebral criticism and academia than to the notion of the passionate creator expressing his emotions through his works. The fact that Kim essentially approached crime as an intellectual exercise can be seen in his refusal to don an extravagant name or outfit, like most Batman foes – instead, suitably, Kim just looks (and sounds) like a smug, pretentious art student who trades on postmodern referentiality and ironic distance.

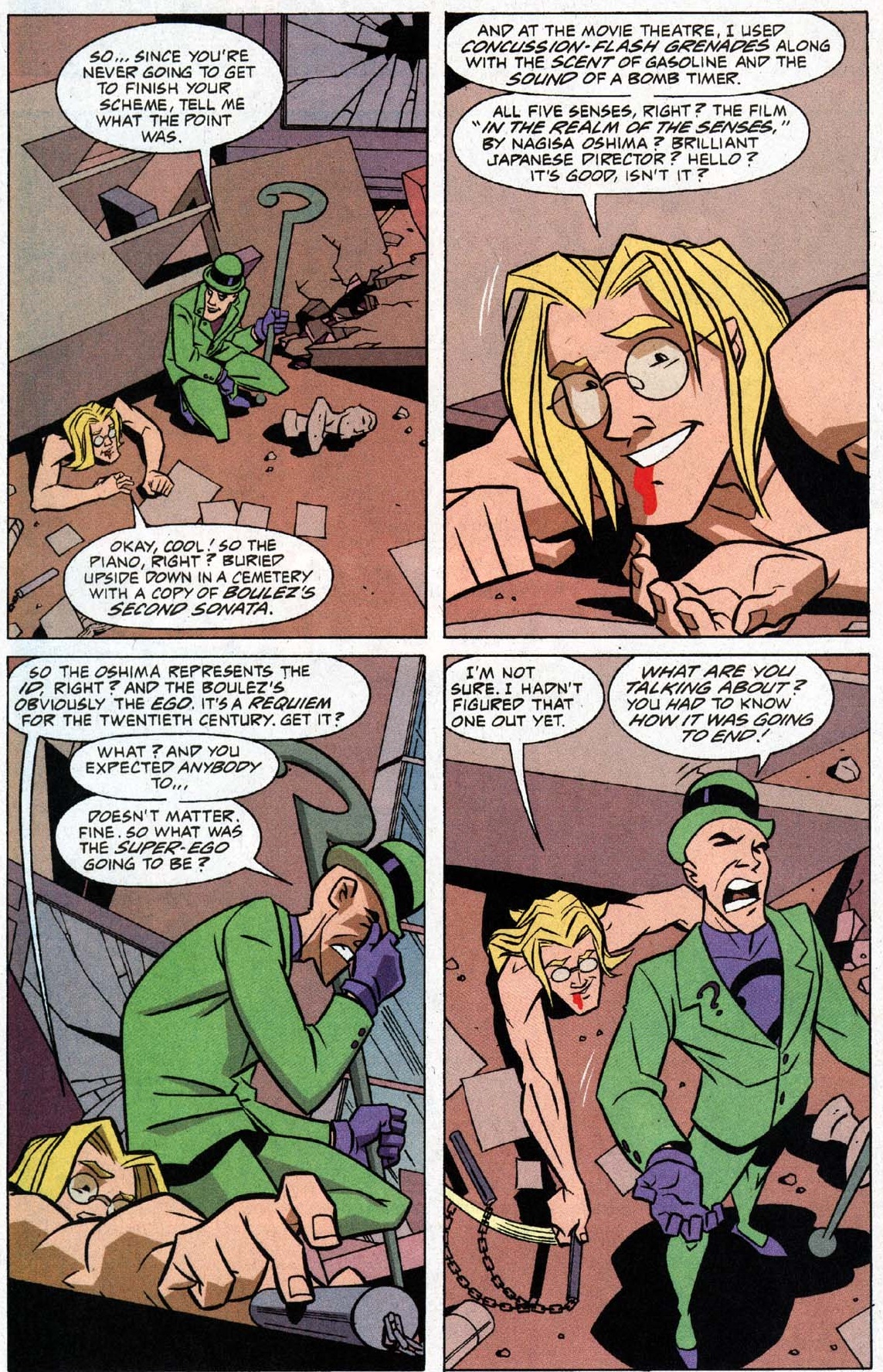

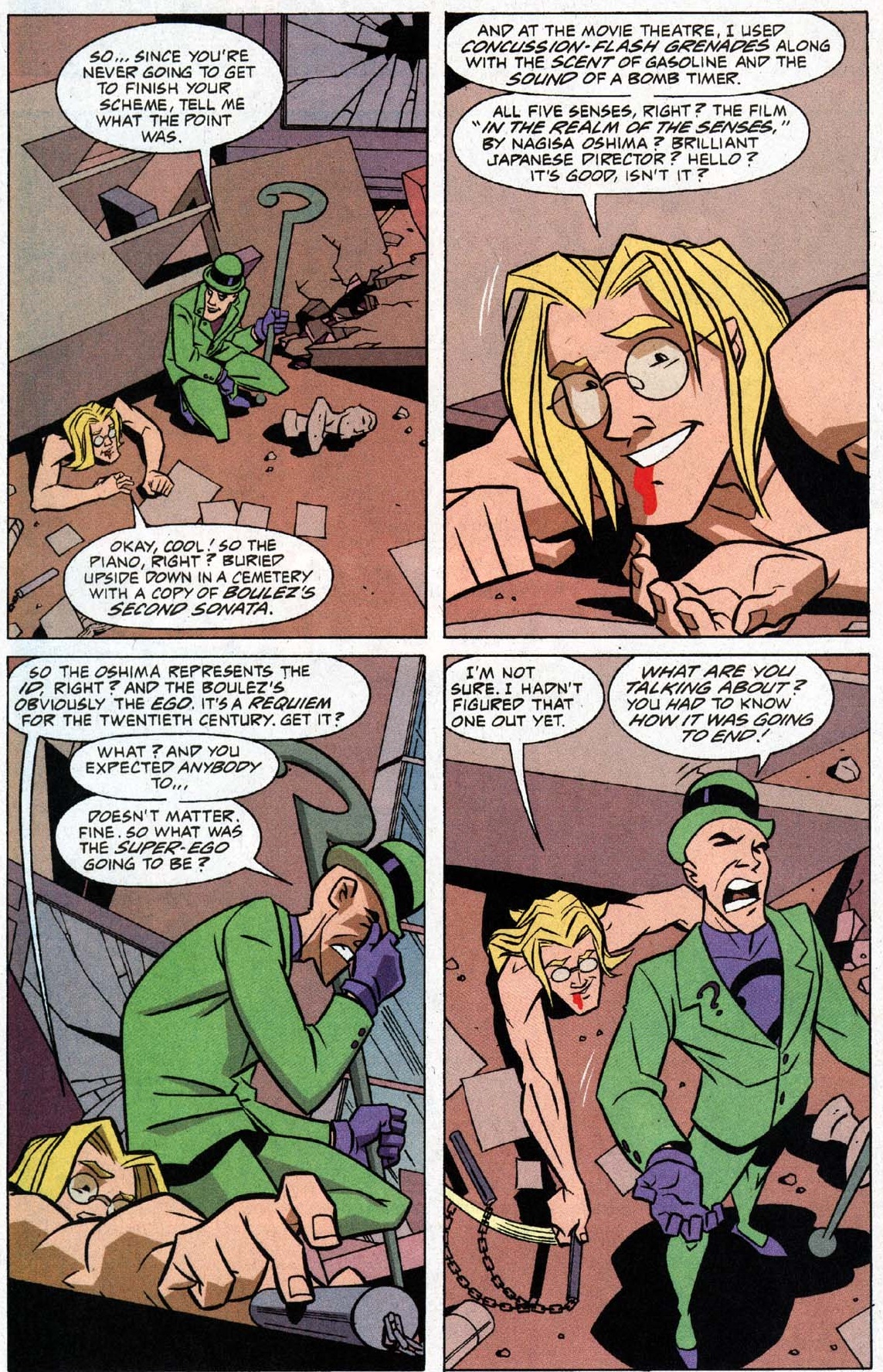

The absence of a memorable visual signifier may explain why the character was never picked up by other writers, even if he did return in a couple of very nifty issues of Gotham Adventures: ‘Identity Theft’ (#56) and ‘The Real Deal’ (#57). Sure, Kim was ultimately just a more exaggerated version of other criminals with an obvious artistic inclination (from the Joker to Calendar Man…), but I think there is gold to be mined in the premise of a highbrow villain who – like some artists – is so committed to his schtick that his schemes become virtually indecipherable to anyone other than himself.

Gotham Adventures #56

Gotham Adventures #56

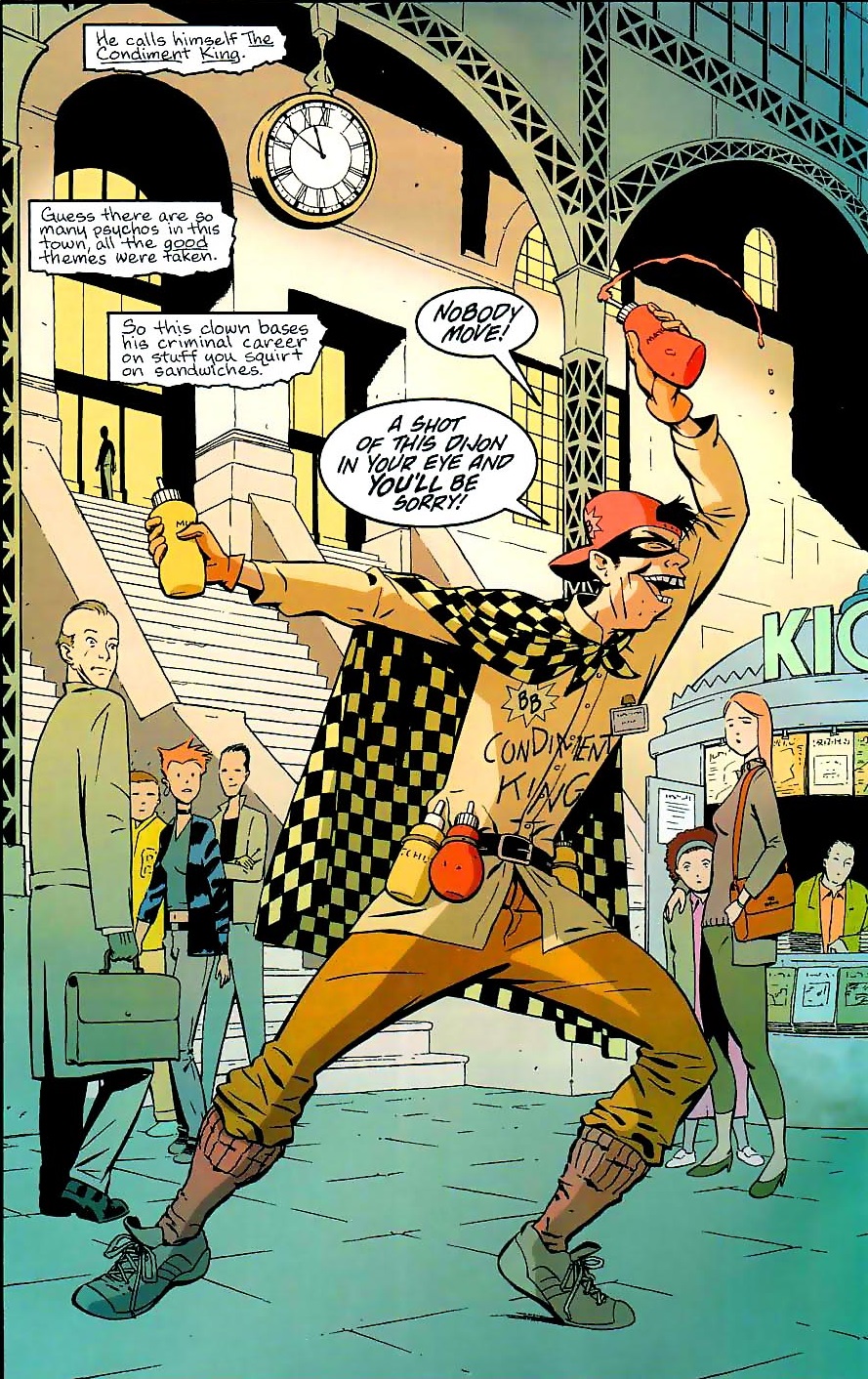

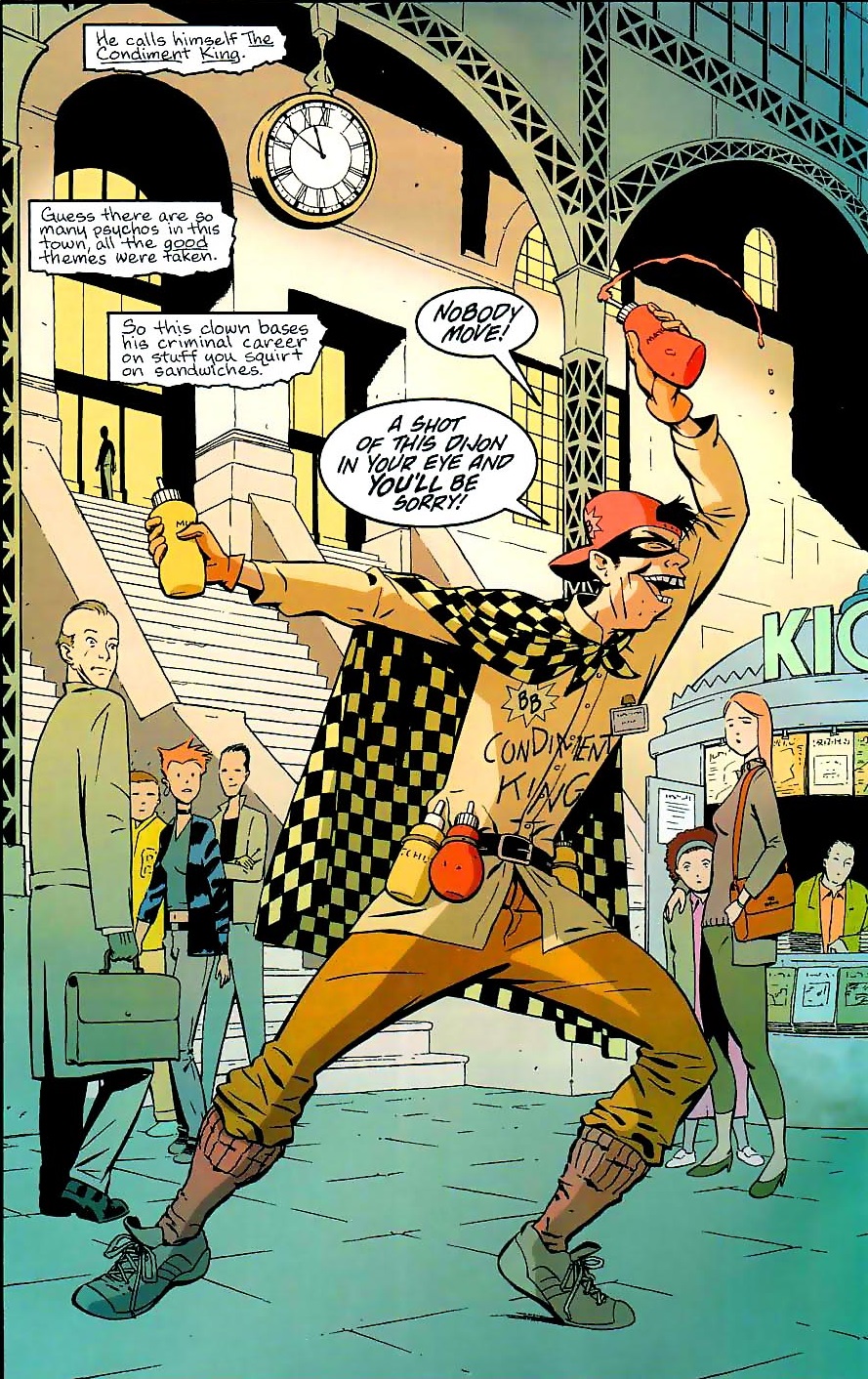

Ironically, the lamer a villain comes to be regarded, the less likely it becomes for s/he to fade into obscurity… After all, infamous creations like Crazy Quilt and Polka-Dot Man ended up evolving into the recurrent butt of jokes about Batman’s rogues’ gallery. This tendency reached a particularly meta dimension in the case of the Condiment King, a condiment-themed thief that was created as a deliberate parody of those sorts of villains and eventually became one of their most notable representatives.

Like Zelda the Great, Condiment King made his debut on television, but his origin was even more tongue-in-cheek. In the Batman: The Animated Series episode ‘Make ‘Em Laugh’ – written by Paul Dini and Randy Rogel (and first aired in 1994) – the Joker used mind control to turn the judges of a comedy competition into absurd costumed criminals, including the Condiment King (other victims became the Pack Rat, who only stole trash, and Mighty Mop, an evil sitcom housewife). Thus, even within the story, CK was supposed to be a joke, or at least the twisted product of a comedian’s delusional mind and the Joker’s slapstick sense of humor, awful condiment puns and all (‘I knew you’d ketchup to me sooner or later. How I relished this meeting.’).

Hell, just look at the guy:

‘Make ‘Em Laugh’

‘Make ‘Em Laugh’

Chuck Dixon later introduced the character into the comics’ continuity, without the brainwashing backstory, as just another Gotham madman, complete with an appropriate civilian name (Mitchell Mayo) and a hilariously offhand explanation for his disorder (‘I guess he took one too many special orders.’). Curiously, in Birds of Prey #37 (January 2002), Barbara Gordon reminisces about something special that happened between her and Dick Grayson the first time they – as the original Batgirl and Robin – fought Mitchell Mayo. The following year, in Batgirl: Year One, Dixon revealed this to have been the first kiss between Babs and Dick, thus retroactively inscribing the Condiment King at the heart of the history of this major romance! (Yep, reading Dixon’s comics back-to-back can be as rewarding as binging the Marvel movies in order…)

Even better than Dixon’s worldbuilding, though, was the chance to see the amazing art team of penciller Marcos Martin and inker Alvaro Lopez amusingly redesign the Condiment King’s look… Here is their take (colored by Javier Rodriguez) on what a more amateurish version of this villain might have looked like when he first got started, including a clear mustard and ketchup motif:

Batgirl: Year One #8

Batgirl: Year One #8

And here is a more stylish, upgraded, Jokerized version, who showed up in the aftermath of the crossover Joker: Last Laugh:

Birds of Prey #37

Birds of Prey #37

(Yep, it’s a condiment-based variation of Batman’s suit!)

Although the Condiment King wasn’t taken seriously from the start, leave it to Chuck Dixon to come up with a way of having your spicy cake and eating it too – i.e. of preserving the character’s inherent ludicrousness yet simultaneously turning him into a dangerous threat. In the comic book version, while the Condiment King was locked up in Arkham Asylum, Poision Ivy taught him all about natural spices and how to weaponize them. Once he broke out, he totally built a mustard gas bomb!

Dixon brought him back one last time, in Robin #171, but it was little more than a cameo… In turn, Lilah Sturges (then writing as Matthew Sturges) gave the Condiment King a more prominent – and ultimately fatal – role in her violent comedy about Z-list villains, Final Crisis Aftermath: Run. Sturges ran with the notion that this was basically a Batman ’66 villain displaced in time, so she filled his dialogue with non-stop gloriously cheesy puns:

Final Crisis Aftermath: Run #2

Final Crisis Aftermath: Run #2

Between reboots, parallel continuities, and the Caped Crusader’s constant multimedia expansion, the Condiment King has continued to pop up as a reliable running gag. He looked quite at home in The LEGO Batman Movie, a metafictional satire that threw a caricature of the Christian Bale/Ben Affleck Dark Knight into a heightened version of Adam West’s world (the film deliberately mimicked the joyful energy of a child playing with toys from disparate branches of the franchise… and, ultimately, with disparate franchises). Back in comics, the Condiment King appeared in Lil Gotham and Harley Quinn, but his presence goes beyond humor titles: notably, Tom King has featured a bunch of cameos by Mayo in his Batman run.

This character’s longevity speaks to the fact that, regardless of the grim façade, one of the core genres operating in Batman narratives has always been an outlandish kind of darkly funny surrealism (typically diluted in crime, horror, and superhero elements). This isn’t just something that comes to the surface when you have comedy writers work on the property, like when Kevin Smith went for it by including in his Cacophony mini-series a genital mutilation joke about Victor Zsasz that built on the logical extension of this serial killer’s bizarre gimmick (if he honors each murder by scarring himself, then sooner or later he has to run out of unscarred skin…). The best creators have embraced this side of the material, whether it’s Grant Morrison opening his epic run with the Joker engaged in a farcically over-the-top slice of mayhem (‘I finally killed Batman! In front of a bunch of vulnerable, disabled KIDS!!!!’) or Paul Dini having Harley Quinn investigate a case about missing dogs, only to then realize her own hyenas had been eating them in the first place (back in Gotham City Sirens #11).

The magic of a solid Batman tale is to pull off this madcap comedy angle while also delivering a thrilling adventure. It may sound like a strange balancing act, but you can find similar blends in a number of other pop cultural phenomena – it’s not such a big leap from the gonzo comics of 1970s’ The Brave and the Bold to the best James Bond films coming out at the time (Diamonds Are Forever, Live and Let Die, The Spy Who Loved Me) or even some of the following decade’s Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicles.

On a more direct level, like I said in the beginning, I have a certain fondness for Gotham City’s small-time criminal losers and I’d like to see them thrive, somewhere. Who knows, perhaps they can find a place in The League of Annoyance…

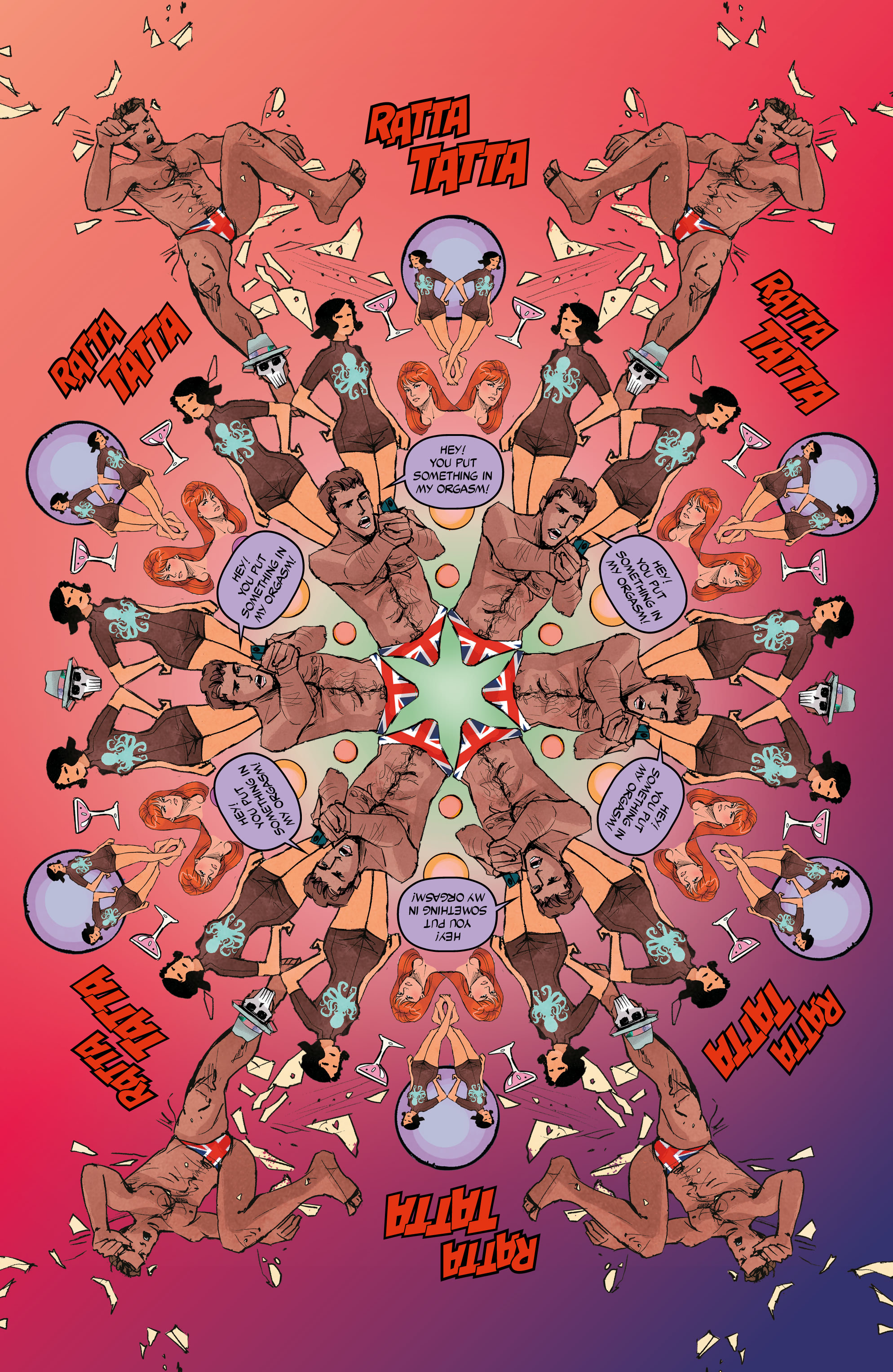

Wonder Twins #2

Wonder Twins #2