Earlier this year, I discussed John le Carré’s Circus novels as the perfect counterpoint to the James Bond branch of spy fiction. Yet there is much more to le Carré’s writing, which has taken this genre into all sorts of interesting directions.

It’s certainly not enough to say John le Carré has a strikingly divergent approach to spy fiction than the one in the 007 franchise. After all, there are many cool alternative paths in terms of writing about espionage, from the intimate metafiction of Ian McEwan’s Sweet Tooth to the quasi-satirical hijinks of Len Deighton’s The Ipcress File. The thing about le Carré is that he has managed to reinvent himself time and time again. As a huge fan of the genre, I don’t find it demeaning per se that he is treated as essentially a ‘spy fiction writer’ – my problem is that this description tends to betray quite a reductive view of what this genre can do and of what le Carré has been able to do with it for a total of 25 books (so far) written across six decades.

Yes, virtually all of John le Carré’s novels involve spies, but should the mere inclusion of spies overshadow everything else? Although there are plenty of recurring situations and character types in his books, they are handled in various different ways and, in any case, as le Carré put it in an interview, the figure of the spy seems ‘almost infinitely capable of exploitation for purposes of articulating all sorts of submerged things in our society.’ Thus, while some of his novels are plot-driven thrillers fueled by espionage and others are personal tales about the psychological toll of being a spy, there are also those in which the spying actually feels mostly allegorical.

Many of them fit easily into classic literary formulas like social drama, political satire, romance, mystery, and character pieces (usually revolving around male midlife crisis), even if the protagonists happen to cross paths, to a smaller or greater degree, with the underworld of foreign intrigue. For example, one of my favorites, 1968’s A Small Town in Germany, reads like a detective tale, as it follows an investigation at the British Embassy in Bonn (and, along the way, captures West Germany’s 1960s identity crisis, with the country’s unmastered Nazi past and emasculated national pride). 1986’s A Perfect Spy is practically a modernist masterpiece and certainly way more psychological than political when compared to his other stuff at the time. Then, of course, you have 1999’s Single & Single, which feels like a proper hardboiled crime yarn, opening with an intense stream-of-consciousness tour-de-force from the perspective of a man who realizes he is about to be killed.

I admit that if you read many of the books in a row it can get somewhat repetitive… Lengthy interrogation scenes come and go, each line and gesture riddled with innuendo. Informants and deserters abound, from Soviet apparatchiks to Russian oligarchs, with several British agents in-between, most of them trying to negotiate a deal that safeguards their family… The endings become a bit predictable once you realize that, more often than not, they’re going to be cynical, downbeat, and deliberately anti-climactic. But even all this adds up to overarching themes developed throughout le Carré’s body of work, which point towards a more general philosophy. For instance, while loose ends are common, they tend to feel less like plot holes than like ingenious ambiguities – the blind spots reflect a world of uncertainties, frustrations, and unconfirmed suspicions.

A key distinction concerns John le Carré’s Cold War and post-Cold War works. I’ve already written about the series of loosely connected (some more than others) novels about the counter-intelligence Circus department. Many of those earlier books were about the moral ambiguity of the Cold War, where both sides did horrible things to each other (and to themselves), their ideals lost somewhere among the political machinations. In a way, the same goes for 1983’s The Little Drummer Girl, which applied a similarly murky approach to the Arab-Israeli conflict.

The post-1991 stuff (which consists mostly of standalone books without recurring characters) is relatively less ambiguous, shedding a stark light on the victims of Western imperialism – for example, 1996’s The Tailor of Panama deals with the US invasion of Panama, 2001’s The Constant Gardener with the pharmaceutical industry’s exploitation of Africa, and 2013’s A Delicate Truth with the ruthlessness of the War on Terror. You may prefer one phase or the other (I tend to fall for the Cold War material), but taken as whole this move from cynicism to idealism is a fascinating shift, especially as one of the leitmotifs in le Carré’s fictions is precisely the tension between pragmatic and romantic politics.

The formal style has also changed. Compared to his mammoths from the seventies and eighties, the post-Cold War books feel somewhat lighter – not that they aren’t dark or dense, but they tend to be tighter page-turners… For instance, 1995’s Our Game is an intelligent, focused thriller about a man who is both on the run and on the hunt – a man who loses everything he holds dear and believes in, like many of le Carré’s protagonists, and who hopes to reinvent himself. (The notion of personal reinvention is a recurring theme, since espionage often involves forging an alternate identity.) Likewise, although Single & Single engages with the final stages and follow-up to the Soviet Union, its main appeal is the way the story is told – it’s a masterfully plotted contraption in which le Carré keeps jumping around, making you work in each new chapter to figure out what the hell is going on by registering clues about each character and situation or anticipating possible connections with other subplots (in short, he makes you feel like an operative yourself as you try to find meaning among the apparent chaos). In turn, his latest, and probably last, novel, Agent Running in the Field, about the Brexit/Trump-era resurrection of Russia as an intelligence threat, seems designed to have a broader mainstream appeal – it’s a nice, breezy read with a couple of great twists near the end, but a far cry from his earlier literary challenges.

Moving beyond the realism of his initial novels, John le Carré’s way with words has allowed him to pull off some more experimental narratives – his immersive, captivating prose can buy a fair amount of suspension of disbelief from readers. Much of The Little Drummer Girl seems like an exercise in adding depth and believability to a Mission: Impossible-style plot (minus the face masks) and testing how far he can get away with it. We’ve seen in countless episodes of that show people coached into to posing as someone else in order to infiltrate the enemy camp, but we never got anything as touching as this passage, about a recently recruited agent, Charlie, and her runner, set just before such an operation:

“One arm went round her shoulder and she shivered violently against it. Leaning her body along his, she turned in to him and reached her arms round him, and hugged him to her, and to her joy she felt him soften, and return her clasp. Her mind was working everywhere at once, like an eye turned upon a vast and unexpected panorama. But clearest of all, beyond the immediate danger of the drive, she began to see at last the larger journey that was stretching ahead of her and, along the route, the faceless comrades of the other army she was about to join. Is he sending me or holding me back? she wondered. He doesn’t know. He’s waking up and putting himself to sleep at the same time.”

John le Carré’s entrancing voice (or voices, since a handful of his stories are told in the first person) and loose pace (with lengthy diversions sacrificing speed in the name of atmosphere) are a big part of the allure, which is why screen versions tend to miss out on much of what makes the books so special. From what I’ve seen, most adaptations are pretty drab and shallow in comparison, even Park Chan-wook’s Little Drummer Girl, despite filling the screen with a series of live pop art paintings.

(I’m usually quite the fan of Park Chan-wook’s visual style – not just in his cult psychological horror thriller Oldboy, but also, notably, in the labyrinthic sexual drama The Handmaiden and in the touching war mystery JSA (which is about the Joint Security Area between North and South Korea, not about the Justice Society of America). Yet I had a hard time accepting the choice to drain le Carré’s novel of all that hard-fought authenticity and turn it into a weird homage to avant-garde theatre (including some godawful acting). The sequences at the terrorist training camp verge so close to caricature that they bring to mind (much funnier) bits from Chris Morris’ Four Lions and Uli Edel’s Baader Meinhof Complex.)

Besides the larger narrative detours, I love it when le Carré gets carried away with small moments, turning the mundane into bizarre (like in his detailed description of a clown act, in Single & Single). There are also the witty turns of phrase, the extended shifts in perspective, the careful fleshing out of the world where each story takes place, the nonchalant way he works in jargon, codenames, and recurring metaphors into the text, letting you gradually pick them up as you go along. The dialogue can be gripping and eloquent, oozing with subtext and snobbish passive-aggressive jabs.

The one trope of spy fiction that le Carré definitely respects is the close relationship with travel literature. His prose often makes you feel like you are visiting foreign lands, like when Charlie arrives in Beirut:

“The street was part battlefield, part building site; the passing street lamps, those that worked, revealed it in hasty patches. Stubs of charred tree recalled a gracious avenue; new bougainvillea had begun to cover the ruins. Burnt-out cars, peppered with bullet-holes, lay around the pavements. They passed lighted shanties, with garish shops inside, and high silhouettes of bombed buildings broken into morning crags. They passed a house so pierced with shellholes that it resembled a gigantic cheese-grater balanced against the pale sky. A bit of moon, slipping from one hole to the next, kept pace with them. Occasionally, a brand-new building would appear, half built, half lit, half lived in, a speculator’s gamble of red girders and black glass.”

Along with the thematic, ideological, and stylistic evolution of John le Carré’s writing, you can also find changes with regard to his depictions of female characters. Sure, with the notable exception of Charlie in The Little Drummer Girl, women do still inevitably end up in supporting roles, mostly providing motivation for the male leads, but there’s no denying that characters like Gail Perkins in 2010’s Our Kind of Traitor or Florence in 2019’s Agent Running in the Field have come to play a much more nuanced and central part.

Speaking of diversity: of course the quality varies as well. For instance, I didn’t particularly care for 2008’s A Most Wanted Man – it has its moments, for sure, but for once the whole thing felt too contrived for my taste. Similarly, 2006’s The Mission Song never fulfilled its initial promise, even though the topic (the plotting of a coup in East Congo) is fascinating and, arguably, there are enough charming passages to compensate.

(Yes, Matt Taylor’s covers for the Penguin editions are pretty awesome…)

On the other end of the scale, if you want proof of John le Carré’s literary genius, perhaps the best place to look for it is in A Perfect Spy, his most ambitious and personal work. This super-dense tale about an operative torn between loyalties is the ultimate rendition of the author’s core themes. It also brings to mind other personal favorites of mine, echoing A Small Town in Germany’s similar investigation into a possible desertion and anticipating 2003’s Absolute Friends, with its saga about a friendship between agents from opposite sides.

As for the post-Cold War stuff, Our Game is perhaps the perfect transitional novel in his oeuvre, providing a powerful glimpse into the generational changing of the guard within the UK secret services and into the boiling ethnic conflicts in the Russian Caucasus (it came out around the time of the First Chechen War). If you want to check out le Carré’s more anti-imperialist works, you could do worse than The Constant Gardener (a murder mystery that spirals into a conspiracy thriller about Big Pharma) or the abovementioned Absolute Friends (which weaves the old revolutionary ideals of 1970s’ Germany into the War on Terror atmosphere).

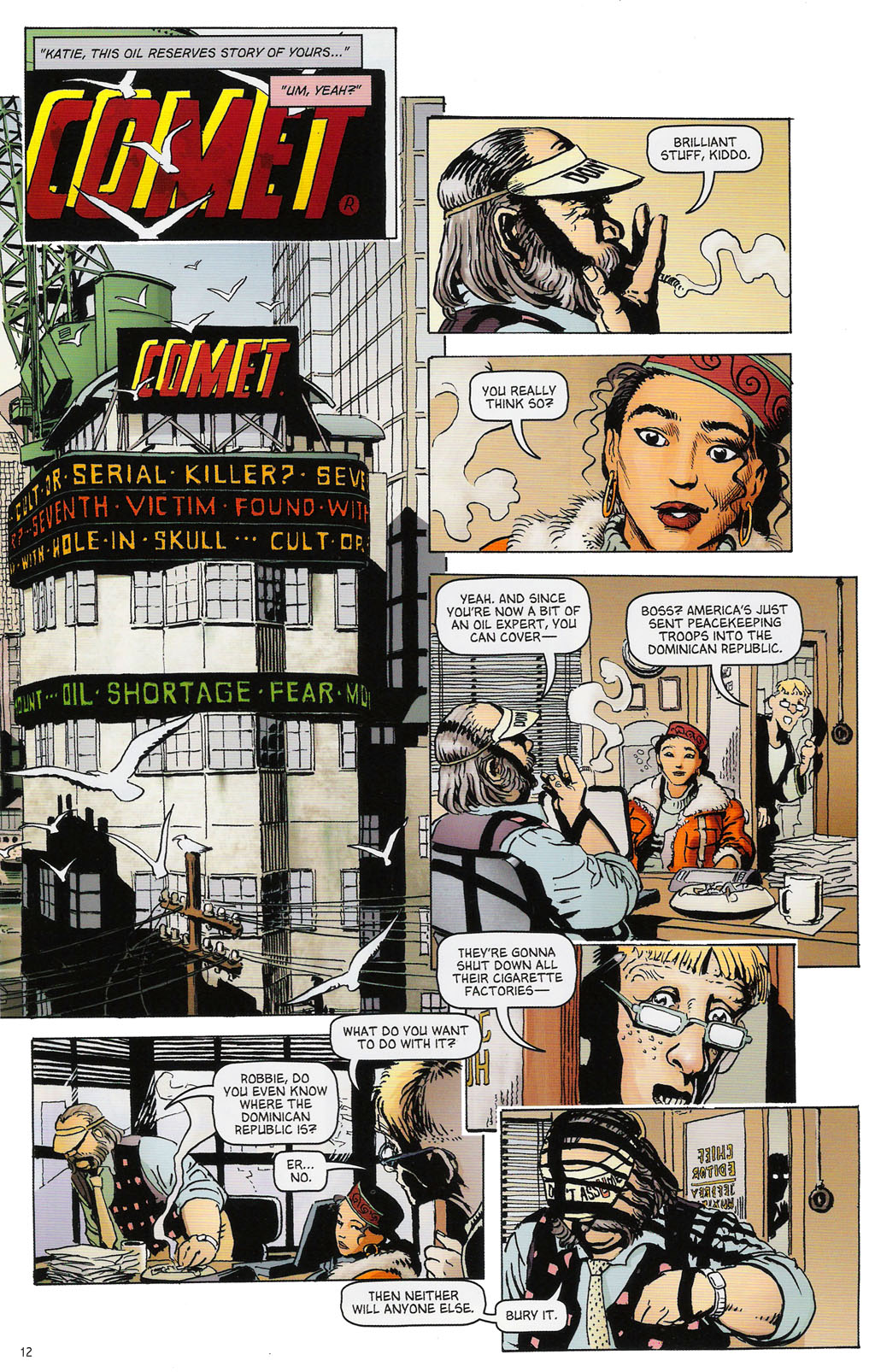

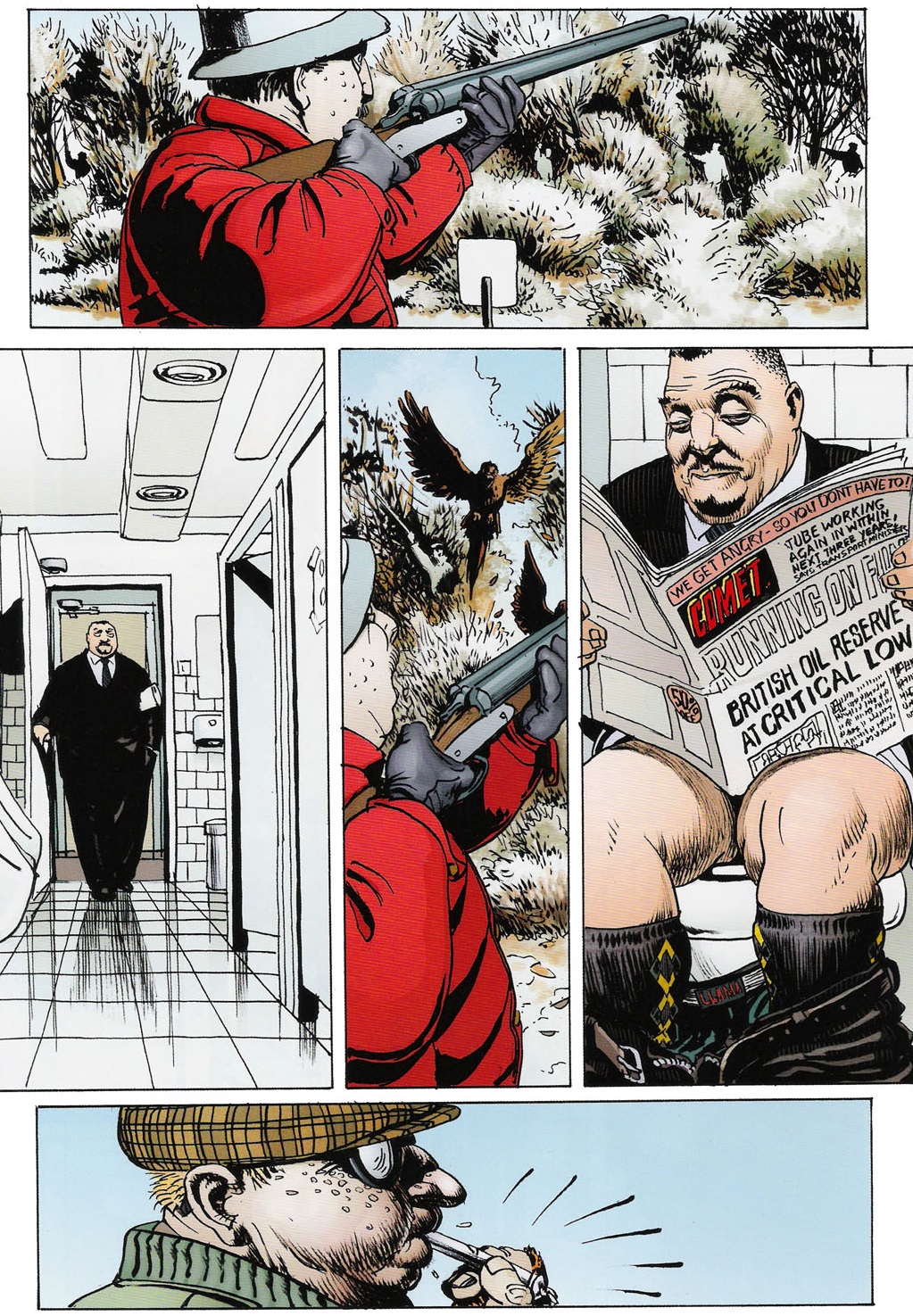

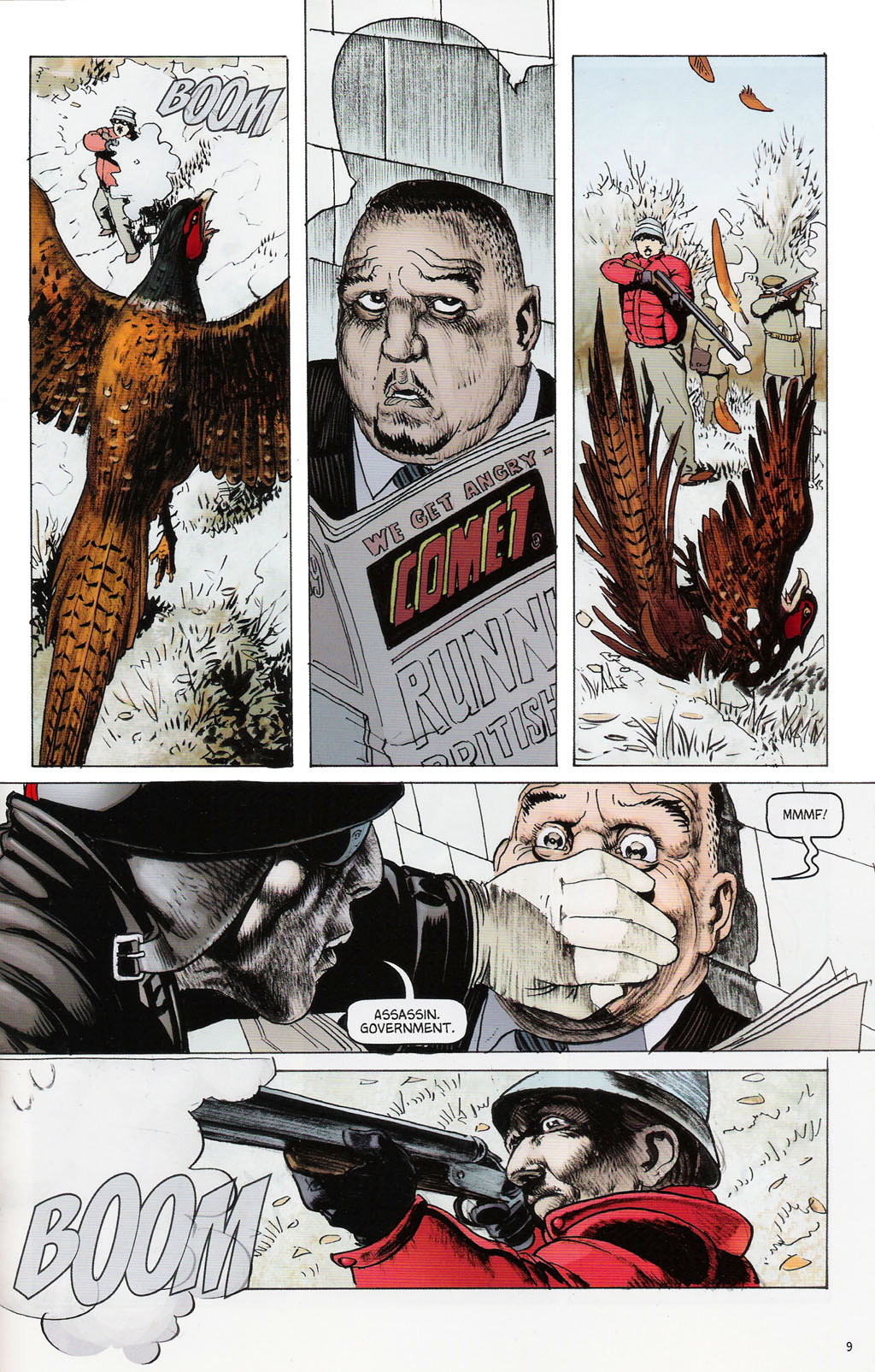

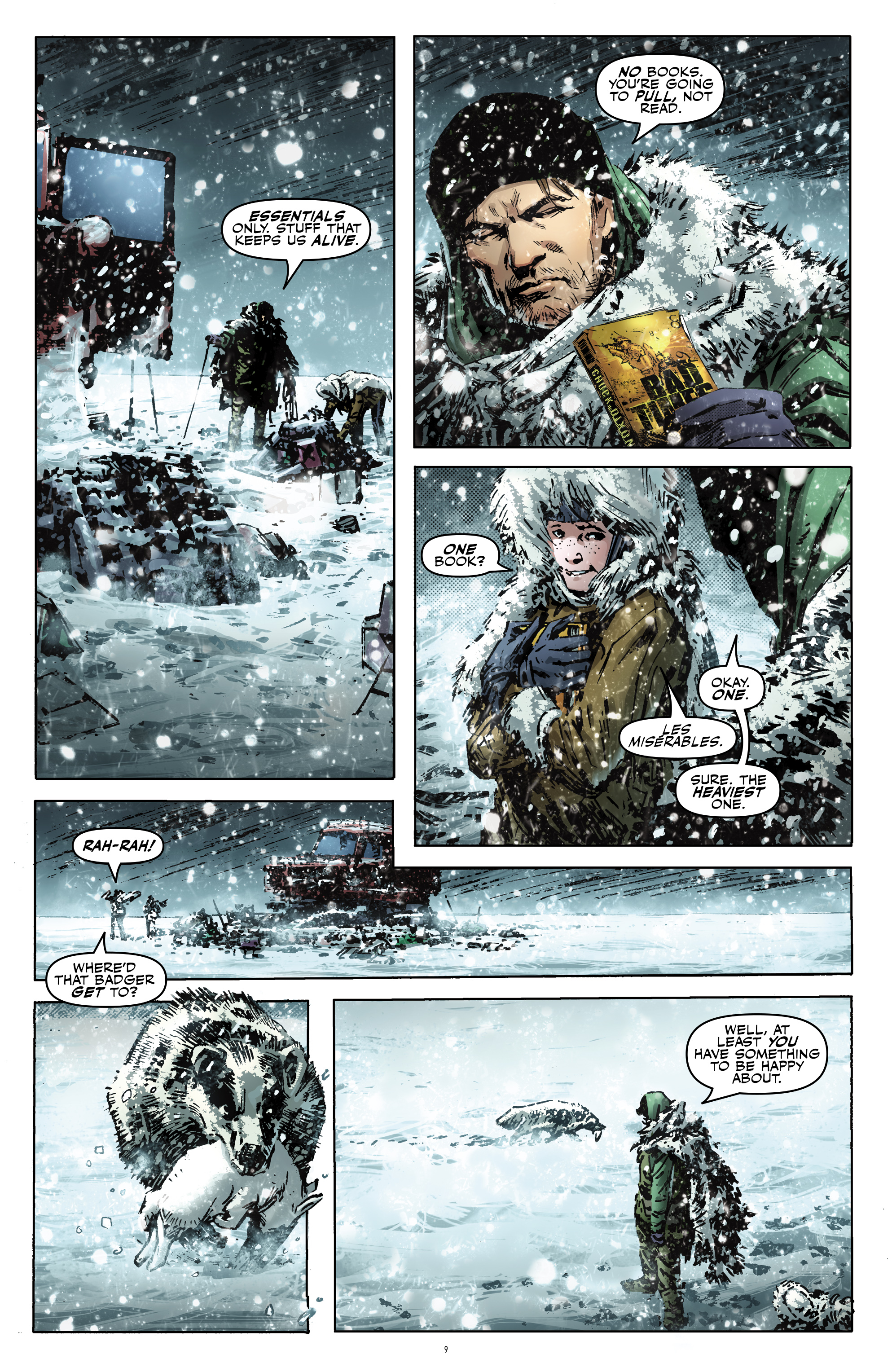

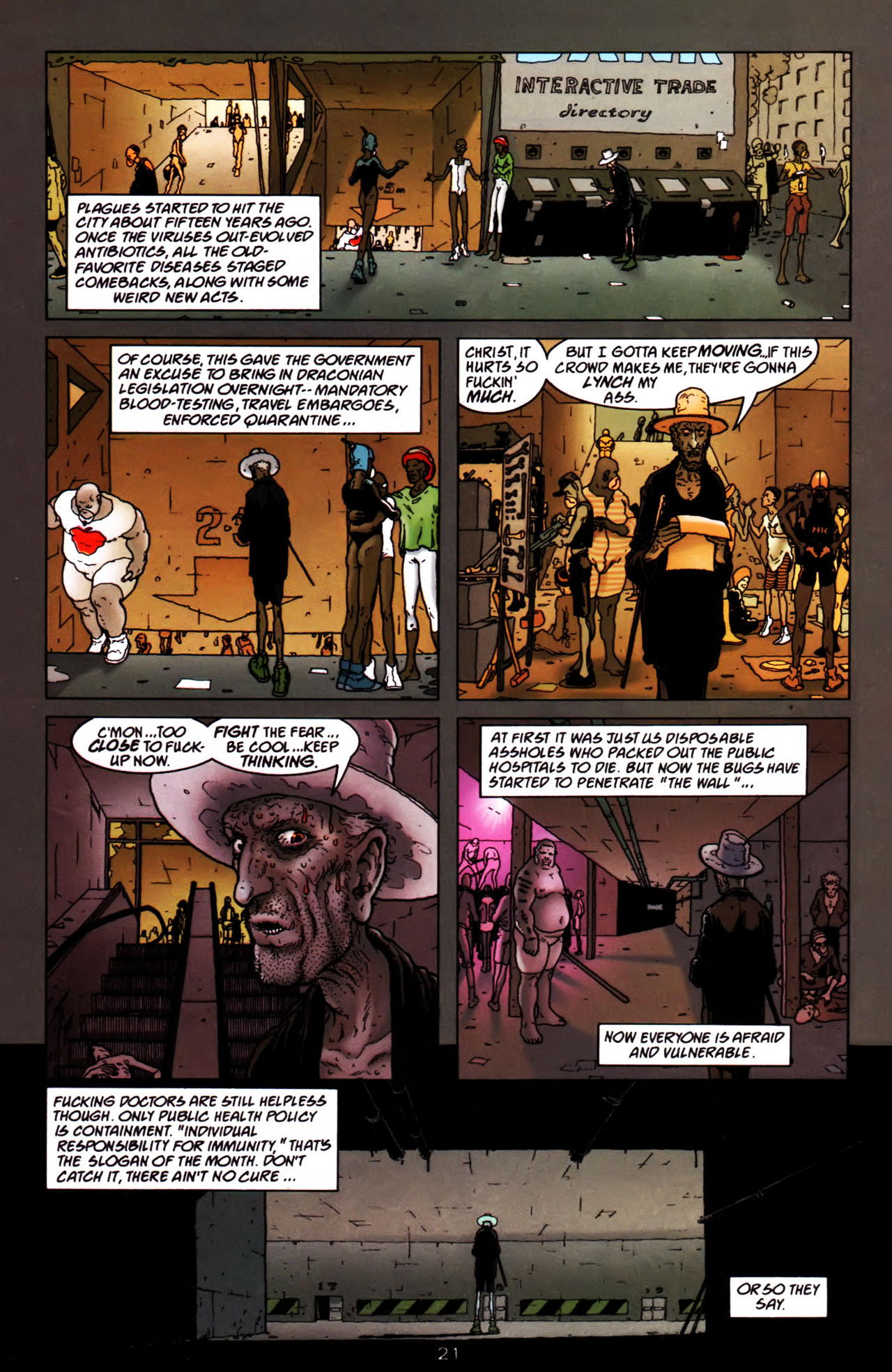

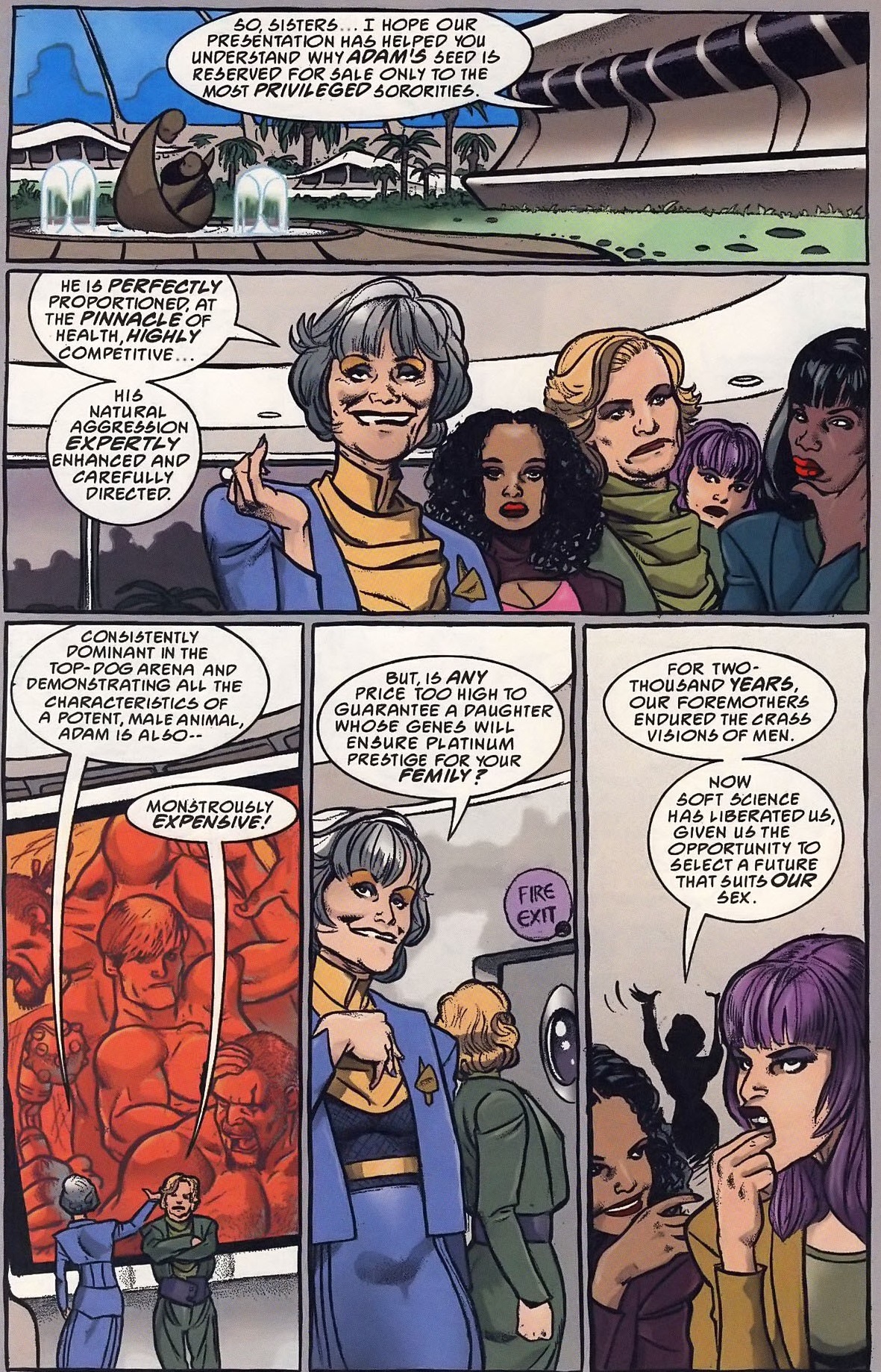

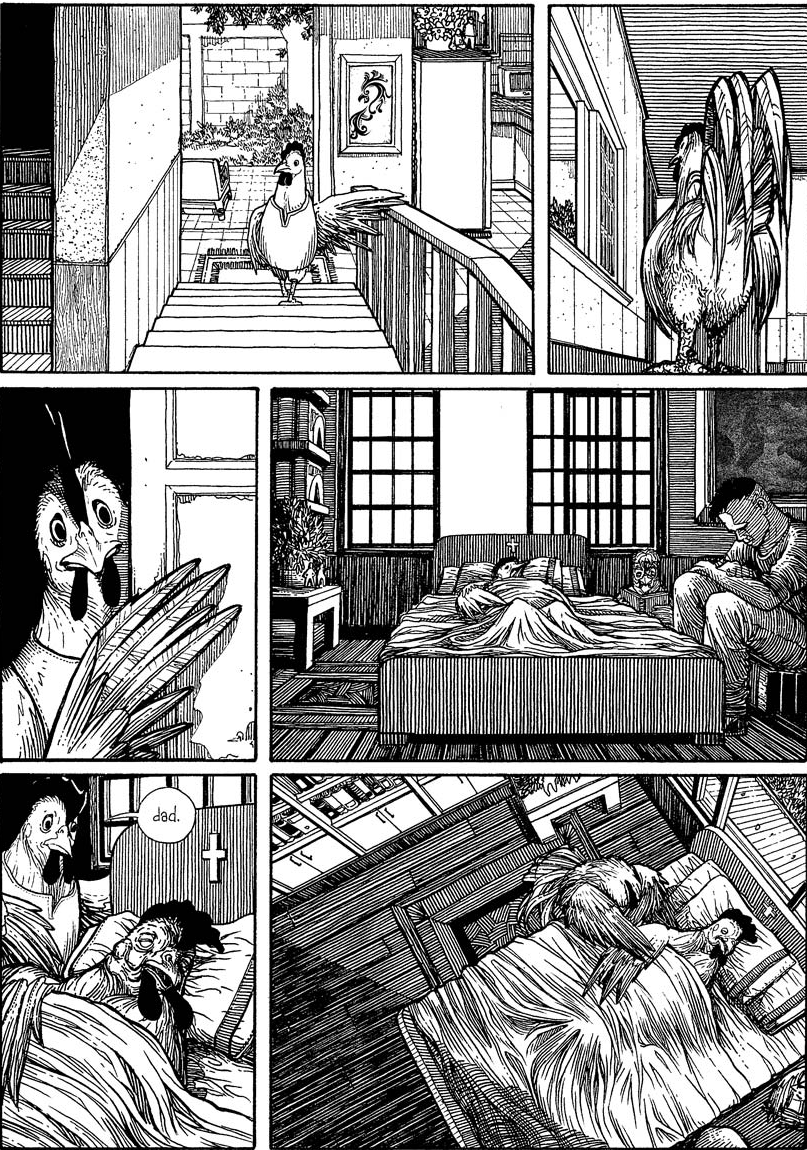

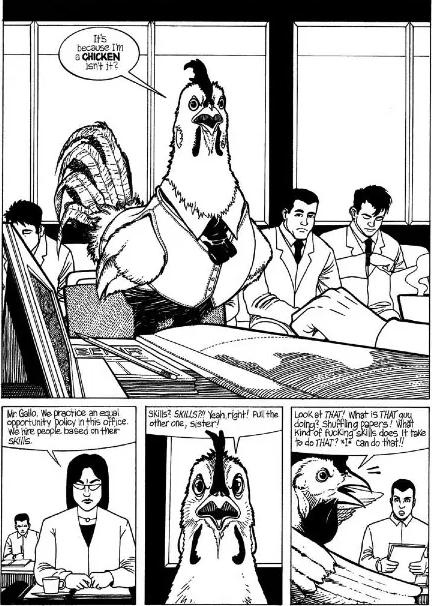

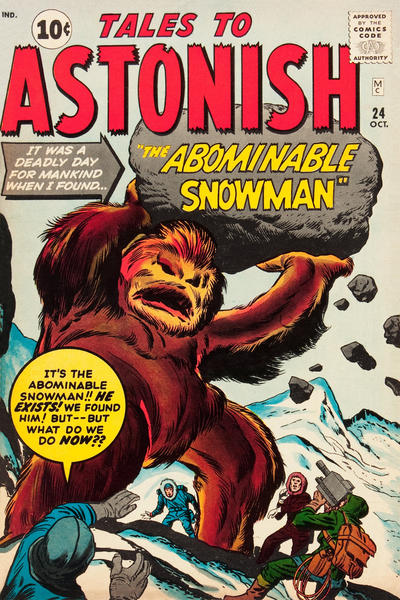

All in all, the main thing that brings John le Carré’s books together is a generally ambitious understanding of spy fiction’s potential. That said, it can be argued that there is also a kind of ‘adult’ sensibility that unites them and which practically qualifies as a subgenre in itself – and one that has been massively influential. You don’t usually find it in mainstream comic books, but it crops up in indie comics every once in a while (I recently came across Mark Askwith’s and R.G. Taylor’s very neat Silencers, for example). Even the recent wave of addictive War on Terror pop thrillers on the small screen (like Homeland, the British Bodyguard, the French The Bureau) are shaped to a large degree by the workings of bureaucracy, moral ambiguity, and complex characterization. And then there is Starz’s Counterpart, which brilliantly applied le Carré’s touch to a sci-fi setting.

The only writer I know who is comparable to John le Carré is Graham Greene – both in the Britishness of the prose and in the ability to mix politics with human drama… I don’t mean Greene’s earlier thrillers, but the more romantic and existentialist stuff like The Quiet American, The Honorary Consul, The Comedians, and – the best of the lot – The Human Factor (which is a kind of inversion of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, following the point of view of the mole). Indeed, le Carré himself has been quite explicit about how much of an inspiration Greene was (hell, The Tailor of Panama is a blatant homage to Our Man in Havana). While the debate on Graham Greene seems to have reached a consensus, though, critics are still discussing whether John le Carré is an espionage author who happens to write well or a great novelist who happens to write spy fiction. Me, I’d say he’s one of the greatest living writers today. Period.