Legends of the Dark Knight #69

Legends of the Dark Knight #69

I’ve mentioned plenty of times in this blog how one of my favorite eras of Batman comics took place in the 1990s when, under the group editorship of Dennis O’Neil, the various titles in the Gotham corner of the DC Universe developed a tight cross-continuity that really fleshed out the city’s institutions and inhabitants (including the ones who didn’t wear silly costumes). Besides the geeky fun of inhabiting such a strange, fully-formed world, the stories tended to be pretty great. Crucially, while most creators grounded the adventures of the Caped Crusader and his team in a relatively consistent reality, they also unabashedly embraced the material’s original appeal as a vehicle for playful tales about surreal criminals and eccentric crimefighters. Thus, for all the violence and pathos, the result was ultimately boisterous and highly entertaining, in contrast to the grim, self-serious tone of the early 2000s.

With that in mind, I’ve decided to provide a guide for those who want to explore this incredible era, especially as most of these stories are scattered around various unordered DC collections (surely more than the ones I identify below, but hopefully this can serve as a starting point for newcomers). Before outlining an ideal reading order for the 1990s’ then-present day continuity, however, this week I’ll list some of the main comics you may want to check out first, since they are set earlier on and loom heavily in the backstory of the main titles.

YEAR ONE [The post-Crisis on Infinite Earths rebooted version of the first year of Batman’s career.]

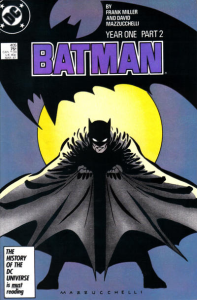

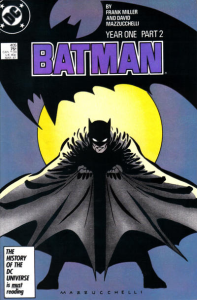

Batman #404-407: ‘Batman: Year One’ (collected as Batman: Year One) [Frank Miller’s and David Mazzucchelli’s classic story-arc reimagined the first encounters between Batman, Catwoman, and then-Lieutenant Jim Gordon (who gets promoted to captain at the end).]

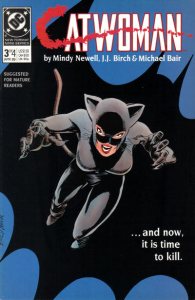

Catwoman #1-4: ‘Metamorphosis/Downtown Babylon/Gothic Baptism/Consecration’ (collected as Catwoman: Her Sister’s Keeper) [Catwoman’s expanded origin, by Mindy Newell and J.J. Birch (aka Joe Brozowski), runs parallel to ‘Batman: Year One.’]

Legends of the Dark Knight #1-5: ‘Shaman’ (collected as Shaman) [Also set at the same time as ‘Batman: Year One’]

Shadow of the Bat Annual #3: ‘Year One: Poison Ivy’ (collected in Four of a Kind and in Arkham: Poison Ivy) [Poison Ivy’s debut, set while Gordon is still a lieutenant]

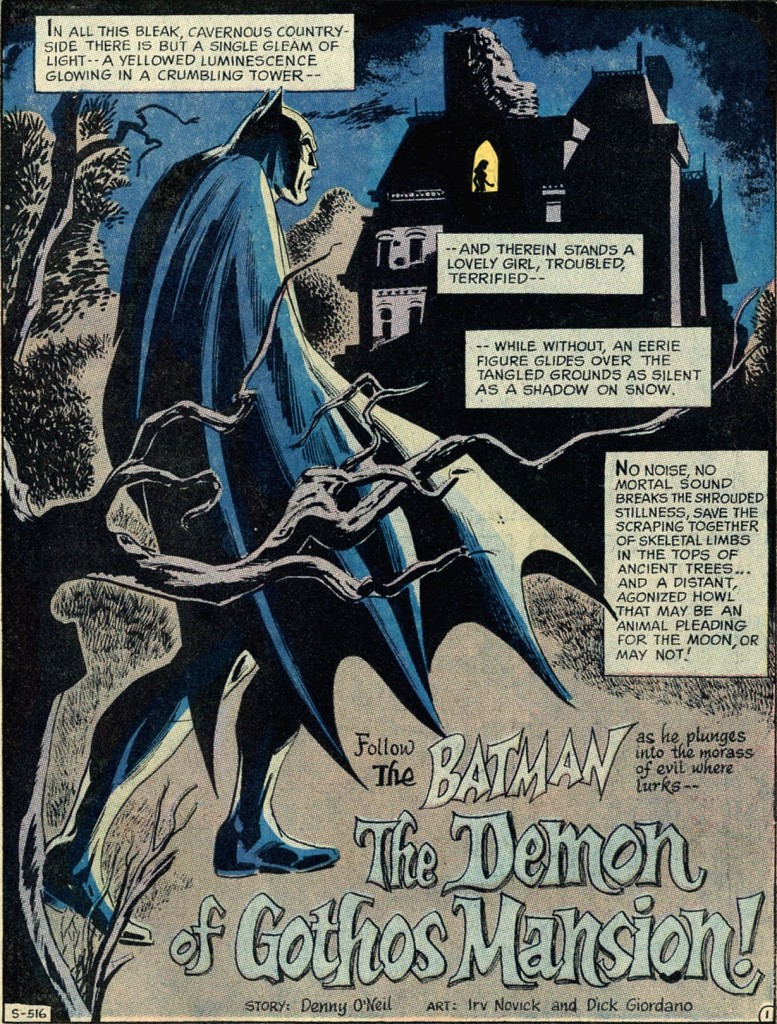

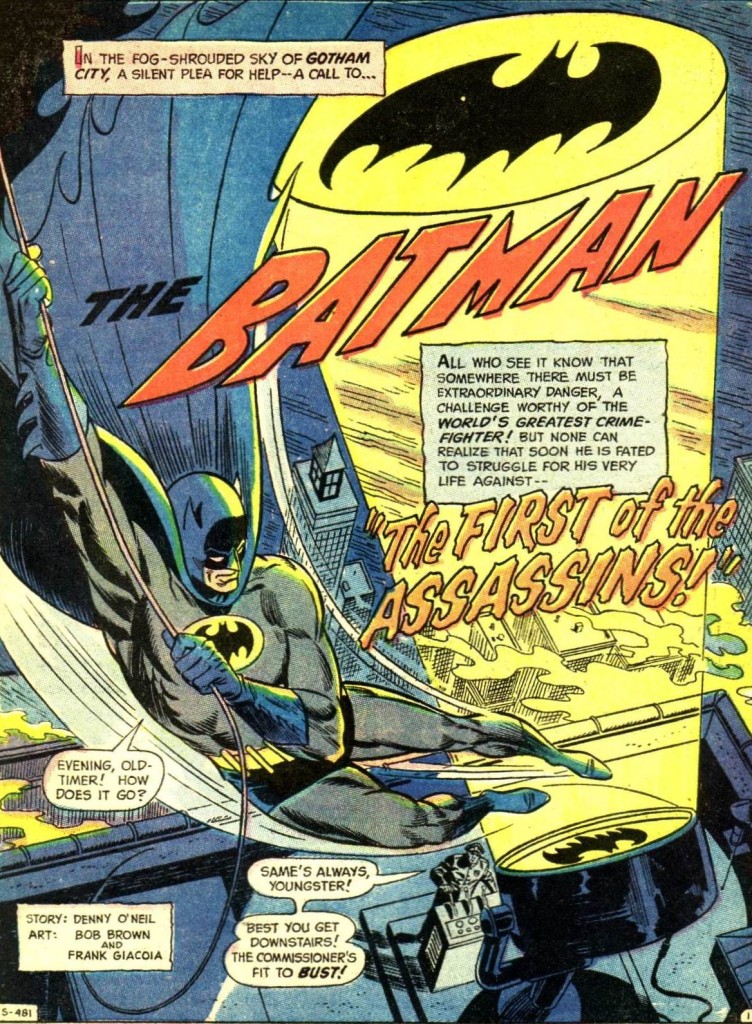

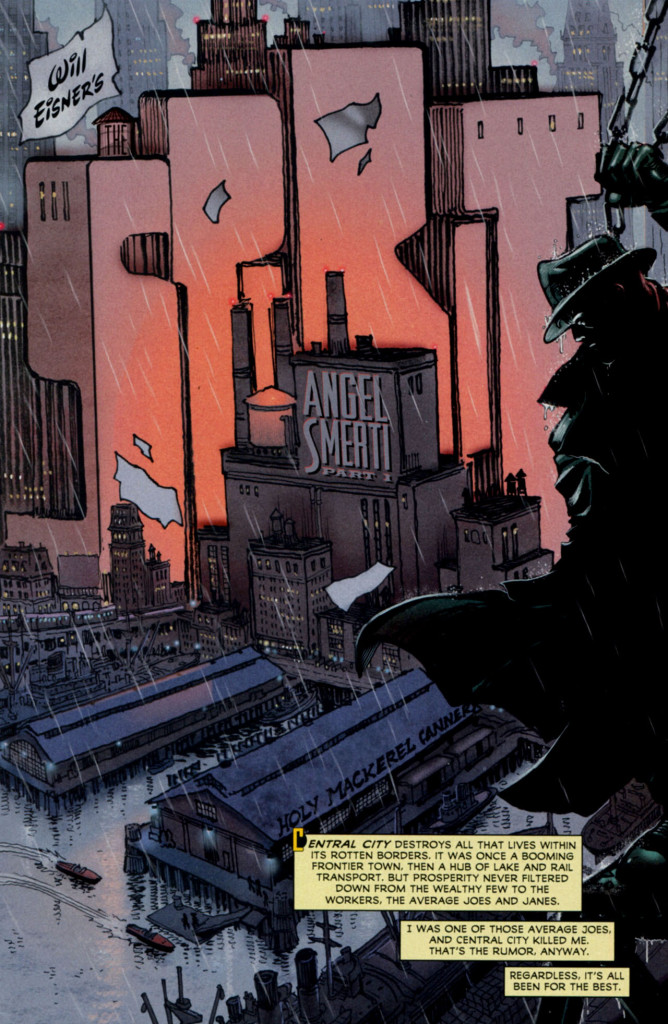

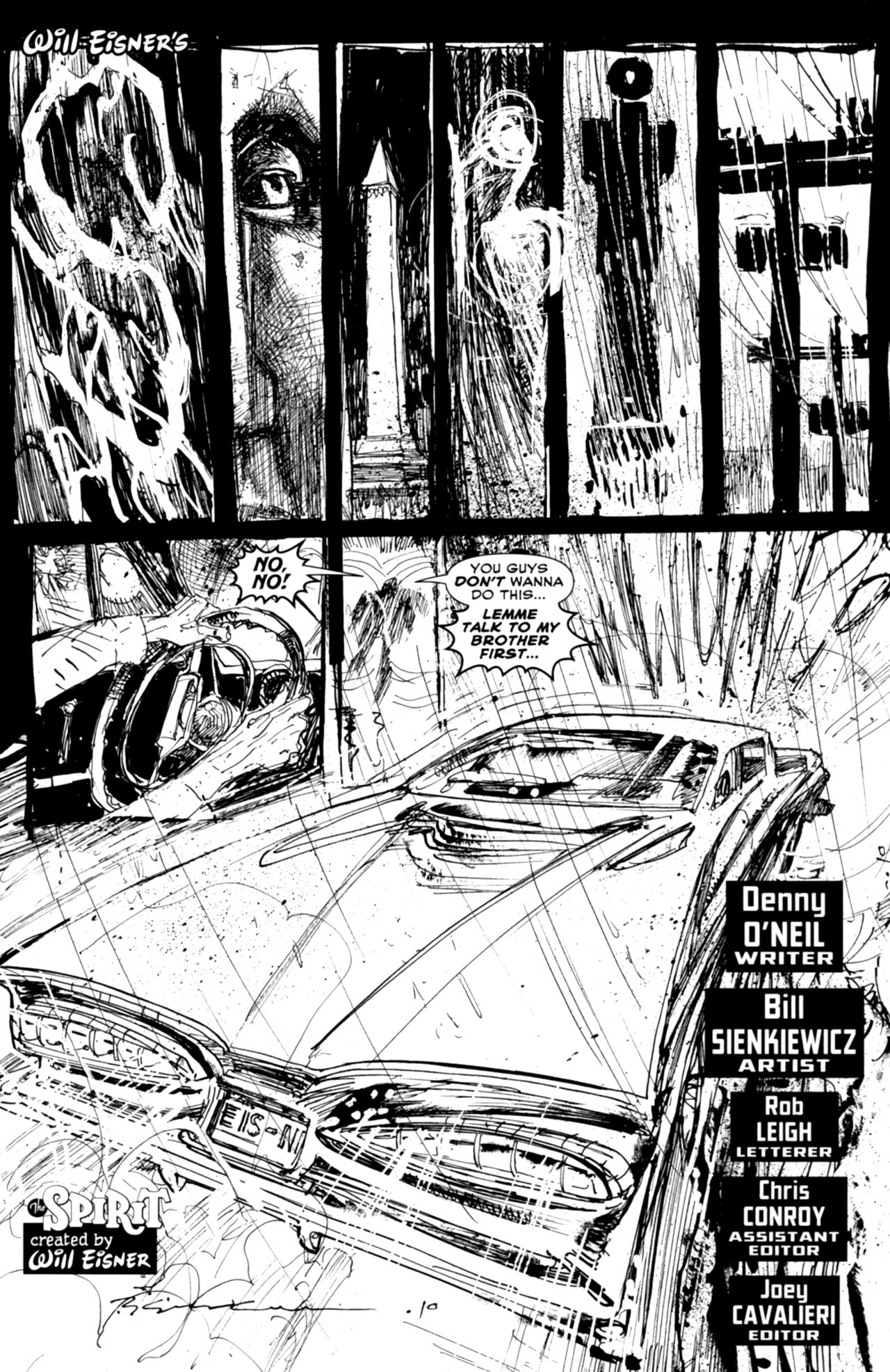

LEGENDS OF THE DARK KNIGHT [No, I’m not including the ‘Batman: Year Two’ arc, which was mercifully ignored by most subsequent creators. Instead, I’ll list most issues of Legends of the Dark Knight from the ’90s, which often took place during Batman’s early years and whose average quality was quite solid (no doubt thanks to the talented editors Andrew Helfer and Archie Goodwin). With constantly rotating creators, this series pushed the franchise’s crime and horror elements in varied, interesting directions as the Caped Crusader dealt with race riots, serial killers, and a handful of mad scientists (including the horny mother of a fascist cyborg). There are other versions of some of these stories (which I will cover in a future post), yet this was the canon used by most 1990s’ comics, not least because many issues were penned by members of the core writing team of Denny O’Neil, Alan Grant, Doug Moench, and Chuck Dixon. In any case, the occasional inconsistencies can be explained away by bearing in mind that these are ‘legends’ – i.e., even if they’re based on actual events, the way these tales are remembered by their protagonists isn’t necessarily accurate in every detail.

In the absence of clear continuity between every arc, I’ll follow the publication order except for when salient aspects provide specific time markers. (This doesn’t apply to Jim Gordon’s hair, which keeps shifting between red and grey – just assume he sometimes dyed it!) If you prefer a strictly chronological sequence of Batman’s life, you can find a detailed one in Collin Colsher’s amazing website The Real Batman Chronology Project.]

Legends of the Dark Knight #50: ‘Images’ (collected in Dark Legends) [Joker’s debut, set not long after ‘Year One’]

The Man of Steel #3: ‘One Night in Gotham City’ (collected in Superman: The Man of Steel and Superman / Batman: The Greatest Stories Ever Told) [Batman’s first encounter with Superman]

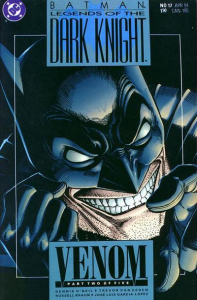

Legends of the Dark Knight #16-20: ‘Venom’ (collected as Venom) [First appearance of the drug ‘venom,’ later used by Bane. Harvey Dent is still District Attorney. Batman’s and Gordon’s partnership is still relatively shaky.]

Legends of the Dark Knight #58: ‘Storm’ [Jim’s son is still a baby, so I’m placing this one here.]

Batman Annual #14: ‘The Eye of the Beholder’ (collected in Featuring Two-Face and the Riddler, Two-Face: A Celebration of 75 Years, and The Caped Crusader, v3) [Two-Face’s debut]

Legends of the Dark Knight #11-15: ‘Prey’ (collected as Prey) [The debut of Professor Hugo Strange (originally, Batman’s very first arch-nemesis) as well as of the Bat-Signal and the Batmobile. Wilson Klass is Gotham’s mayor.]

Legends of the Dark Knight #6-10: ‘Gothic’ (collected as Gothic) [The Bat-Signal must have been around for a bit. The Batmobile is also sighted.]

Legends of the Dark Knight #41: ‘Sunset’ [In this hilariously preposterous comic, Batman’s inner narration mentions the ‘short months’ he has been doing his thing, which is pretty ambiguous… Since he already has the Batmobile, I’m placing it here.]

Legends of the Dark Knight #42-43: ‘Hothouse’ (collected in Collected Legends of the Dark Knight and Arkham: Poison Ivy) [Poison Ivy’s debut took place ‘last spring,’ but the Bat-Signal and (an improved) Batmobile are already around, so this must take place around here.]

Legends of the Dark Knight Annual #5: ‘Wings’ (collected in Four of a Kind and Arkham: Man-Bat) [Man-Bat’s debut. The first part of the issue (in which Batman creates his Batwings) is set before ‘Prey,’ but the story lasts over a month and the climax should take place somewhere around here, because it features a new (bat-headed) Batmobile.]

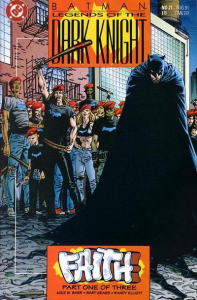

Legends of the Dark Knight #21-23: ‘Faith’ [Properly introduces Leslie Thompkins, who had a cameo in ‘Shaman.’ (Although apparently set around here, I think it can work even better if read right before Robin Annual #4, since it finishes with a Dick Grayson cameo.)]

Legends of the Dark Knight #24-26: ‘Flyer’ [This bonkers comic is set eighteen months after Batman’s debut.]

Legends of the Dark Knight #114: ‘Playground’ [Also set eighteen months after Batman’s debut.]

Detective Comics Annual #8: ‘Questions Multiply the Mystery’ (collected in Four of a Kind) [Riddler’s debut (told in flashback). At least the bulk of it must take place before ‘Blades,’ which has a couple of Riddler cameos.]

Legends of the Dark Knight #32-34: ‘Blades’ (collected in Collected Legends of the Dark Knight and Tales of the Batman: Tim Sale)

Legends of the Dark Knight #35-36: ‘Destiny’ (collected in Other Realms)

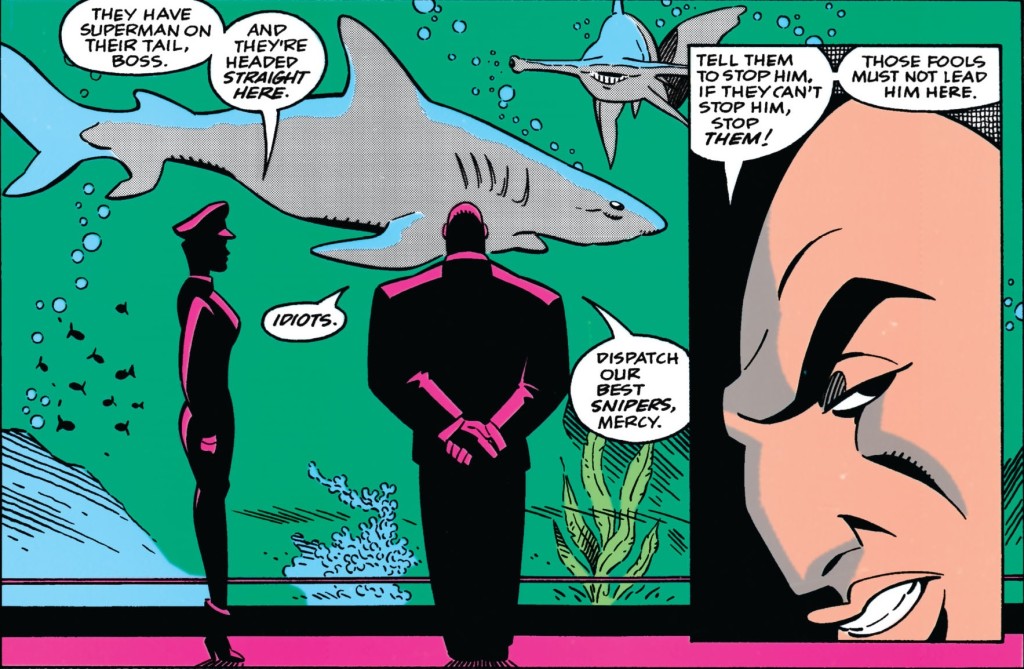

Legends of the Dark Knight #37: ‘Mercy’

Legends of the Dark Knight Halloween Special: Ghosts (collected in Haunted Knight) [As a rule, I’d say Jeph Loeb’s and Tim Sale’s Halloween tales belong in their own alternate continuity, but this is a nice little introduction to Bruce Wayne’s relation with Lucius Fox. It can also serve as an intro to the Penguin, so it comes before ‘Mask,’ where he has a cameo.]

Legends of the Dark Knight #39-40: ‘Mask’ (collected in Dark Legends)

Legends of the Dark Knight #44-45: ‘Turf’

Legends of the Dark Knight #46-49: ‘Heat’

Batman Annual #19: ‘Year One: Scarecrow – Masters of Fear’ (collected in Four of a Kind and Arkham: Scarecrow) [Scarecrow’s debut. It can be set anytime after ‘Prey,’ but I’m placing it here just because new readers may enjoy recognizing this rogue in the cool prophetic vision drawn by Arthur Ranson in ‘Tao.’ In any case, it definitely comes before ‘The Sleeping,’ where the Scarecrow gets mentioned.]

Legends of the Dark Knight #52-53: ‘Tao’ (collected in Dark Legends and Batman: International)

Legends of the Dark Knight #64: ‘Terminus’

Legends of the Dark Knight #0: ‘Viewpoint’ [This story includes several images from future issues, thus serving both as a promotional preview and as a narrative foreshadowing of what lies ahead.]

Legends of the Dark Knight #65-68: ‘Going Sane’ (collected as Going Sane) [Batman says he has faced the Joker twice already, but we haven’t seen their second confrontation, which apparently left quite an impression on the Clown Prince of Crime… (In my head-canon, it was a version of ‘The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge!‘ with Gordon as captain instead of commissioner.)]

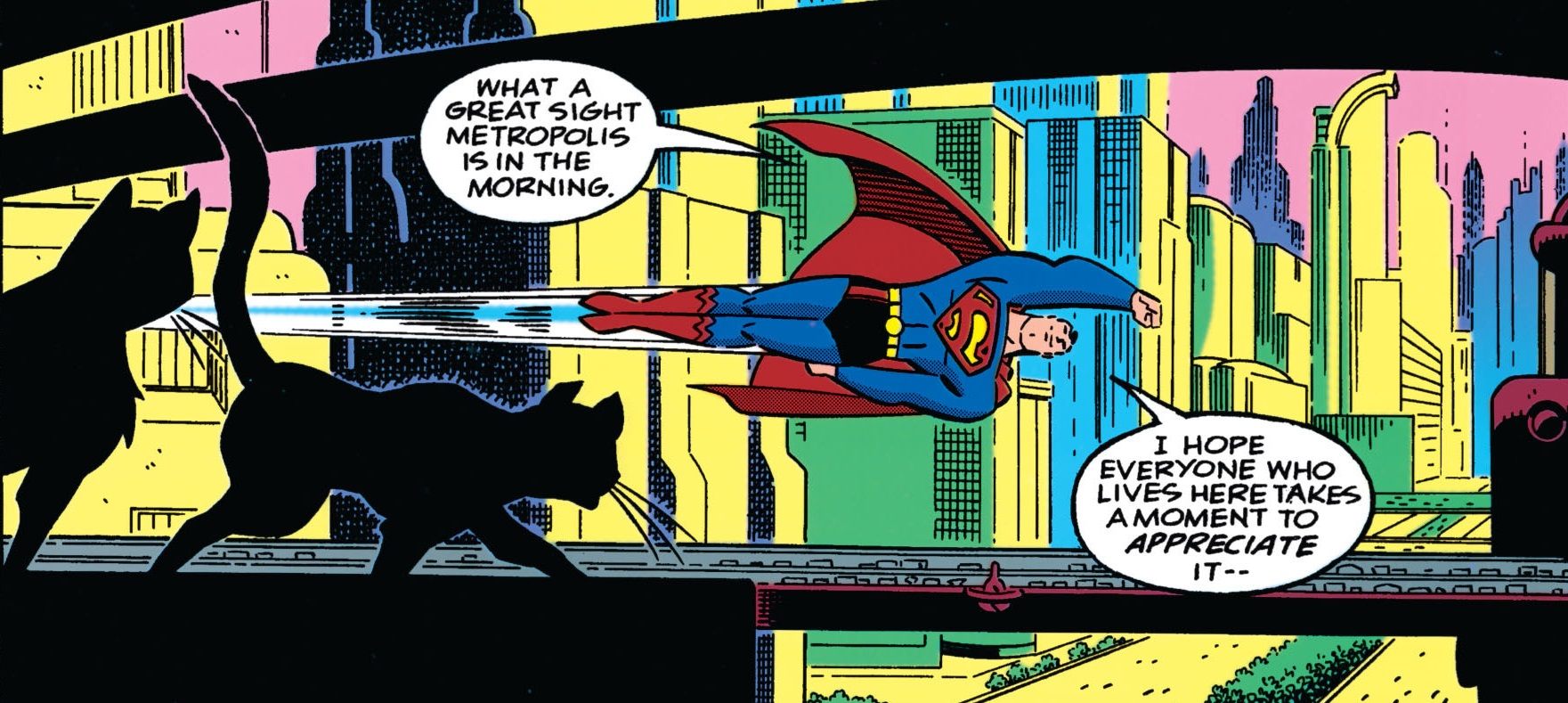

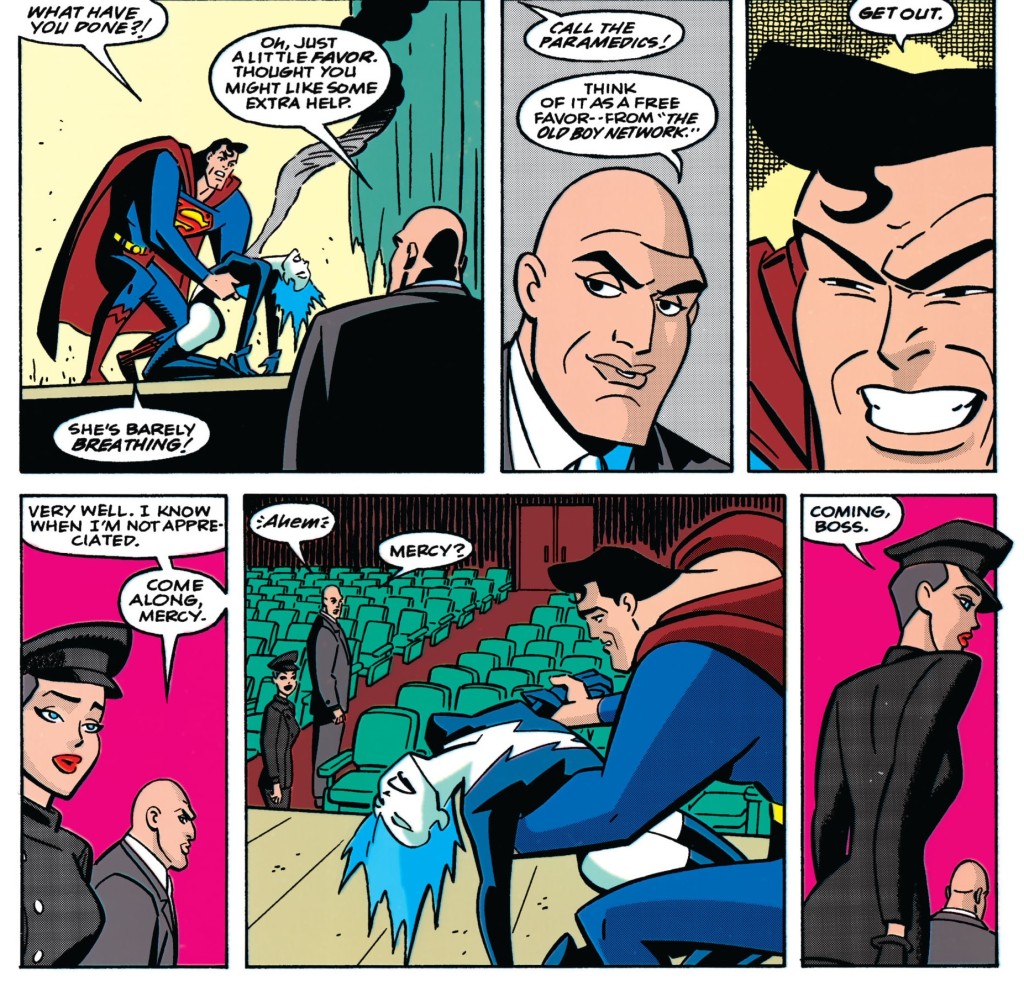

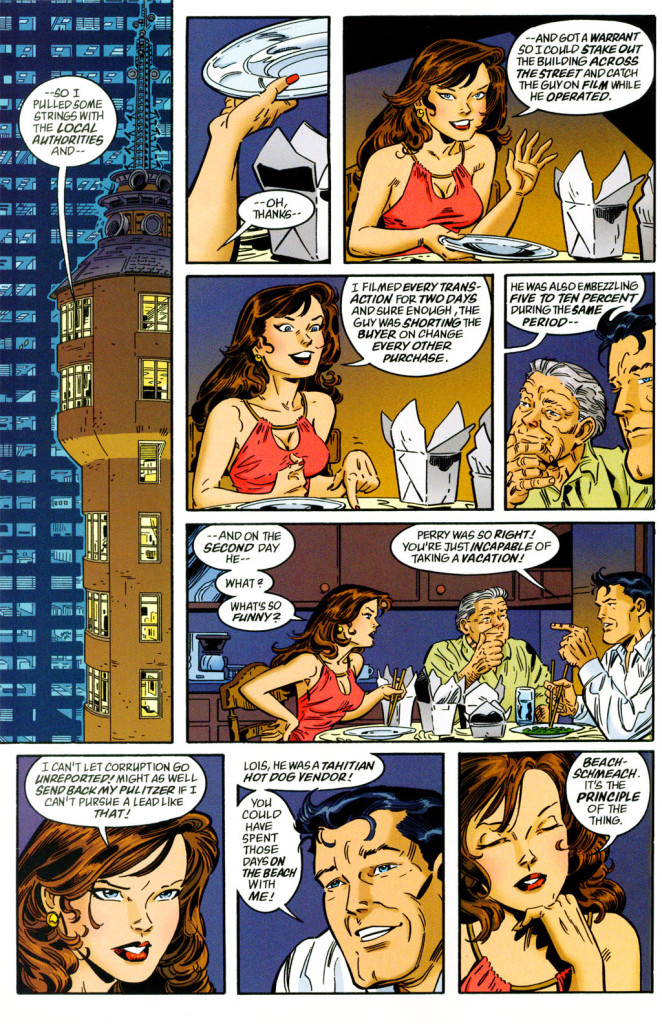

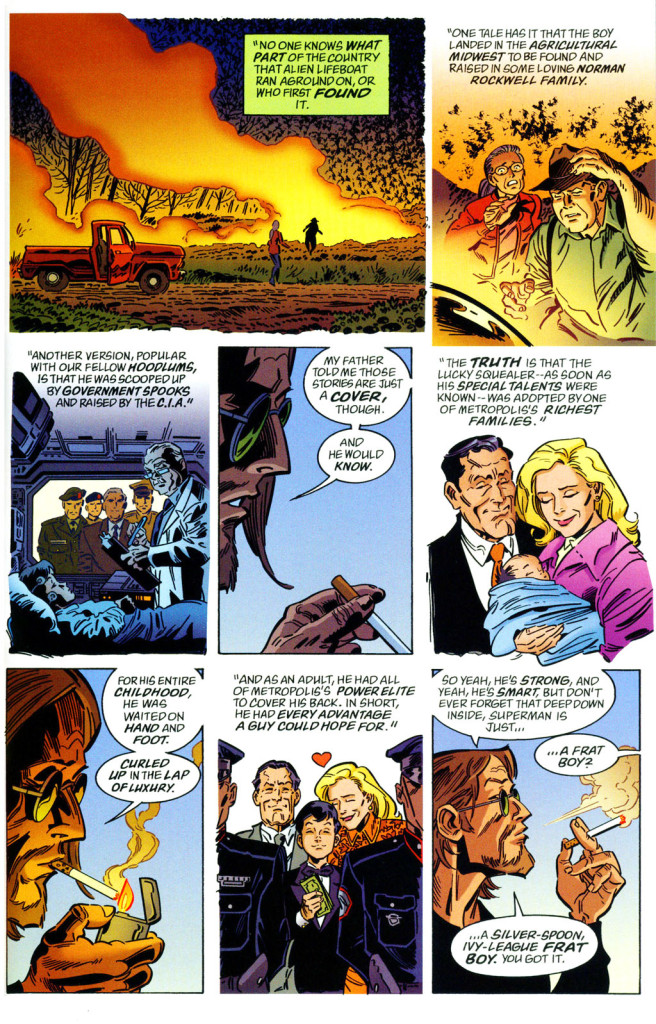

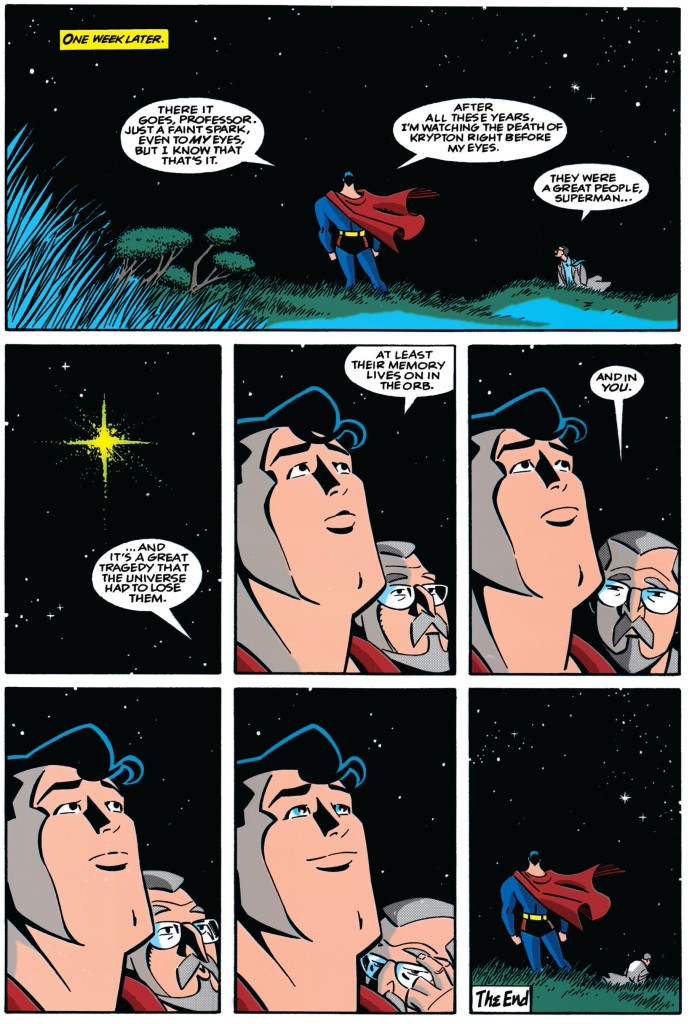

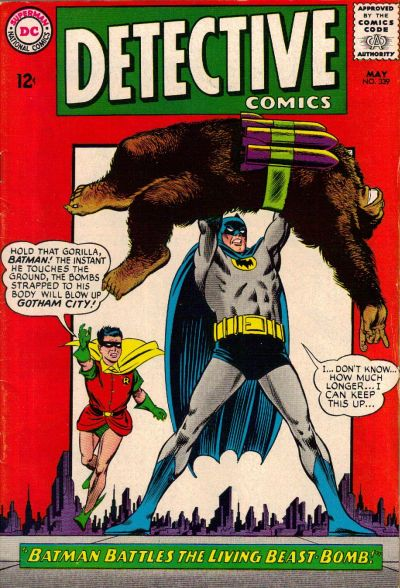

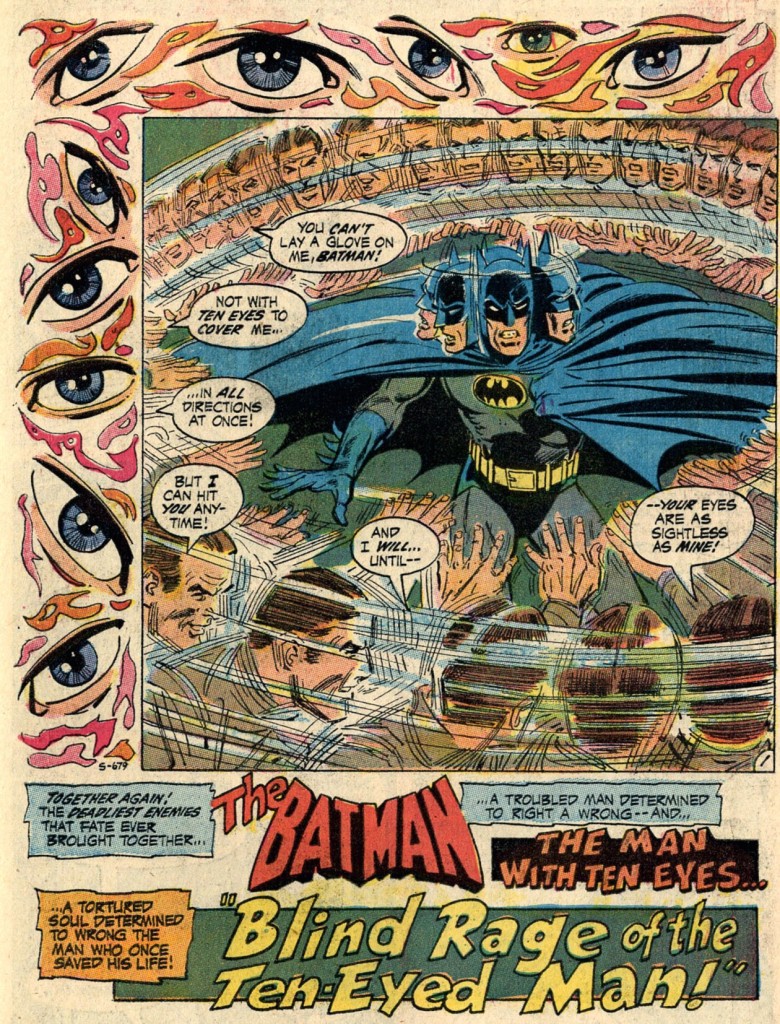

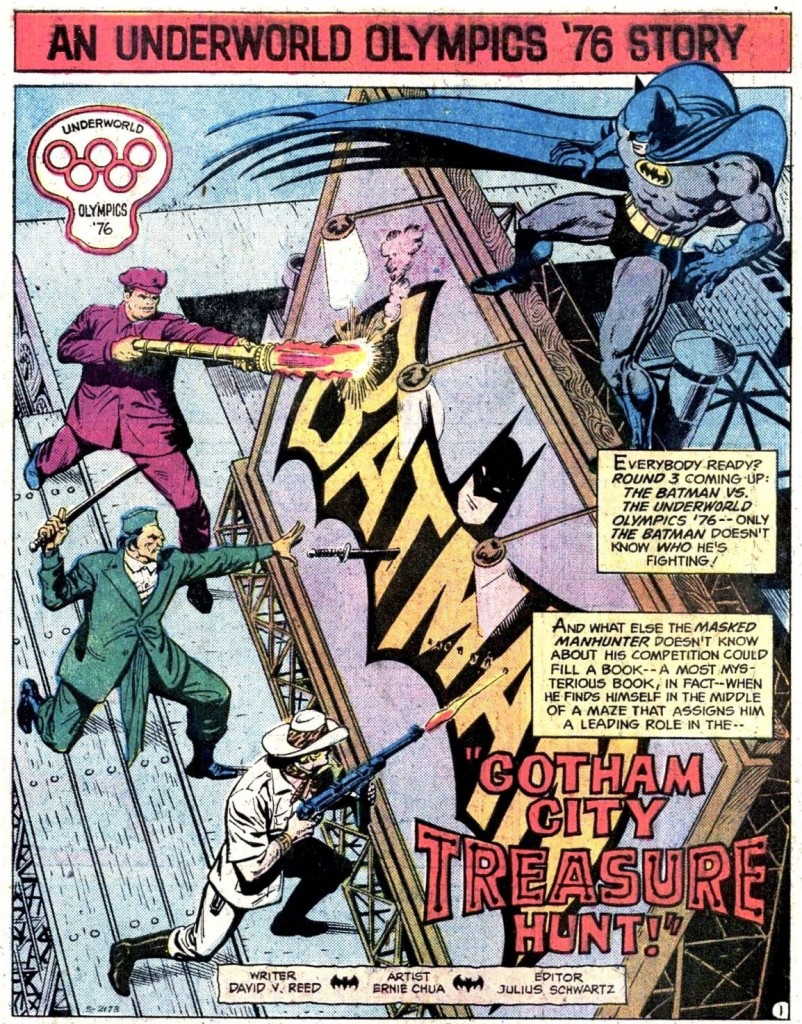

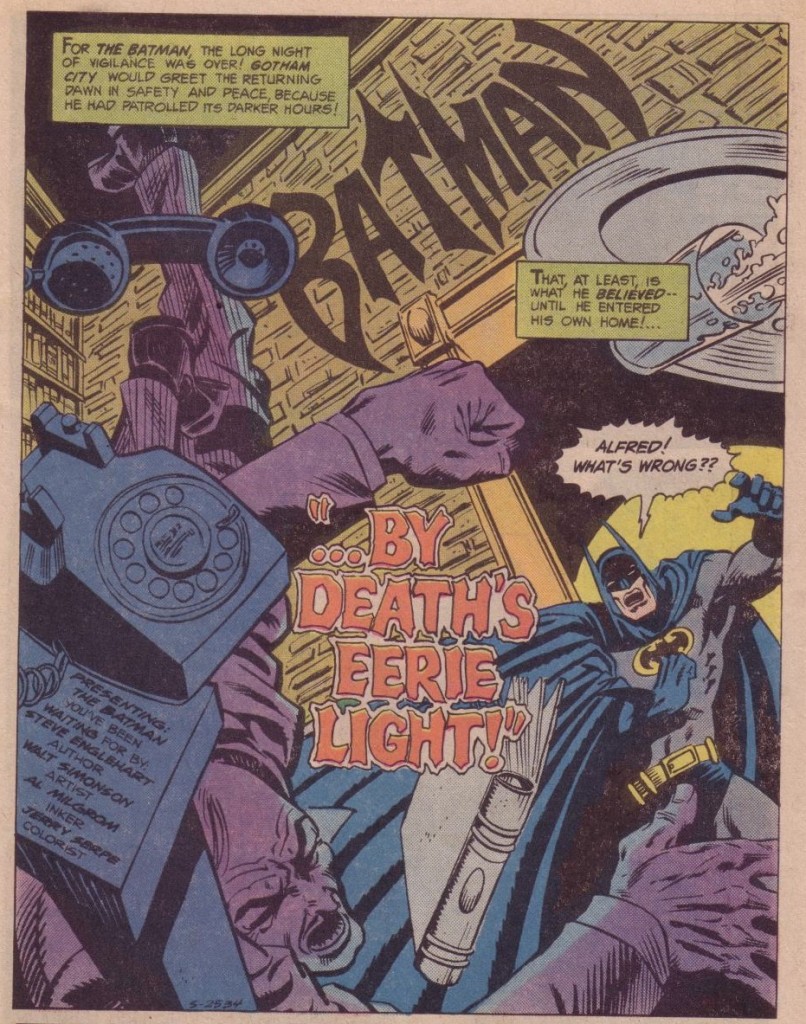

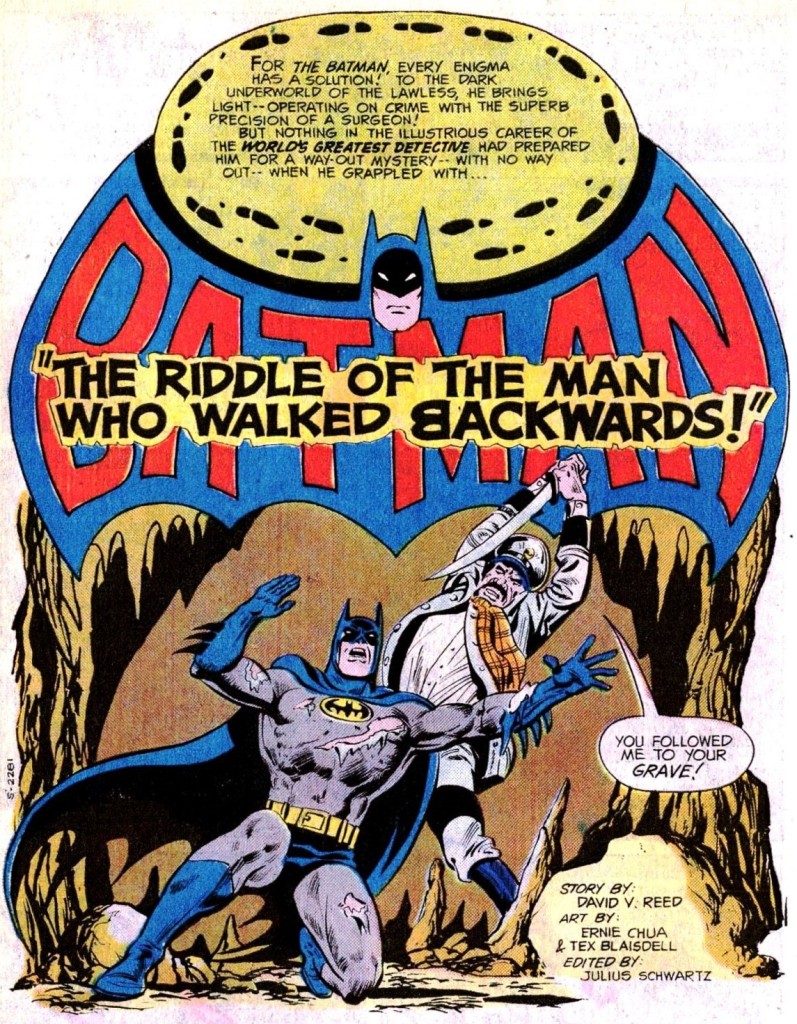

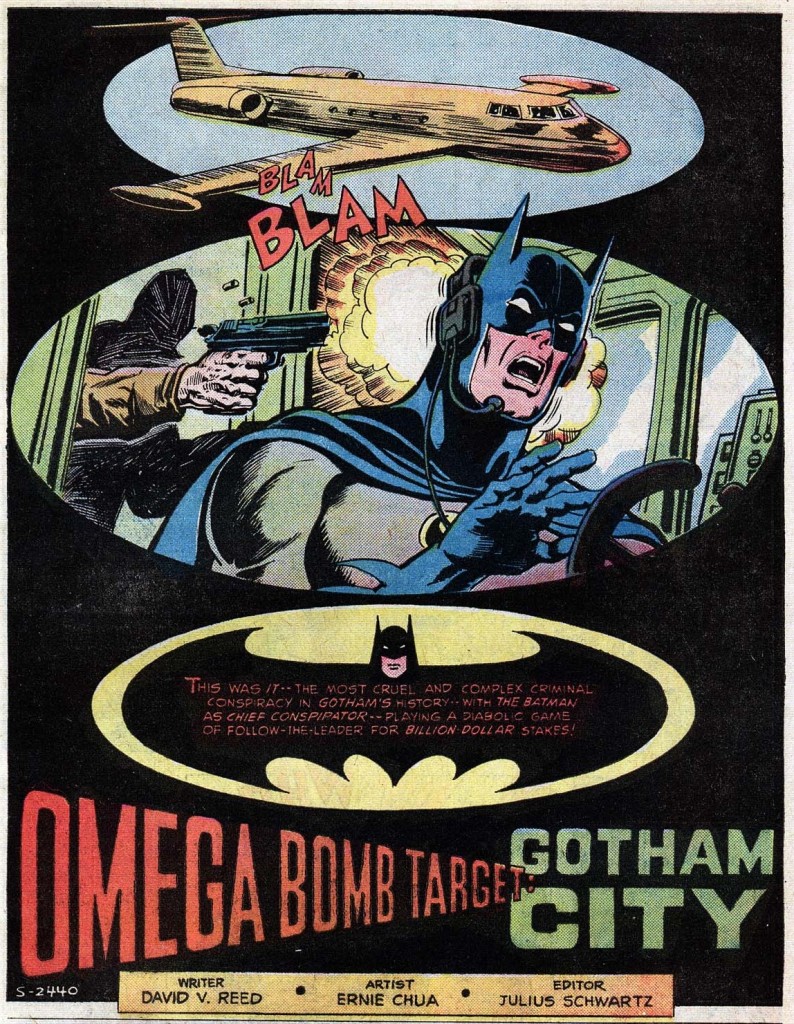

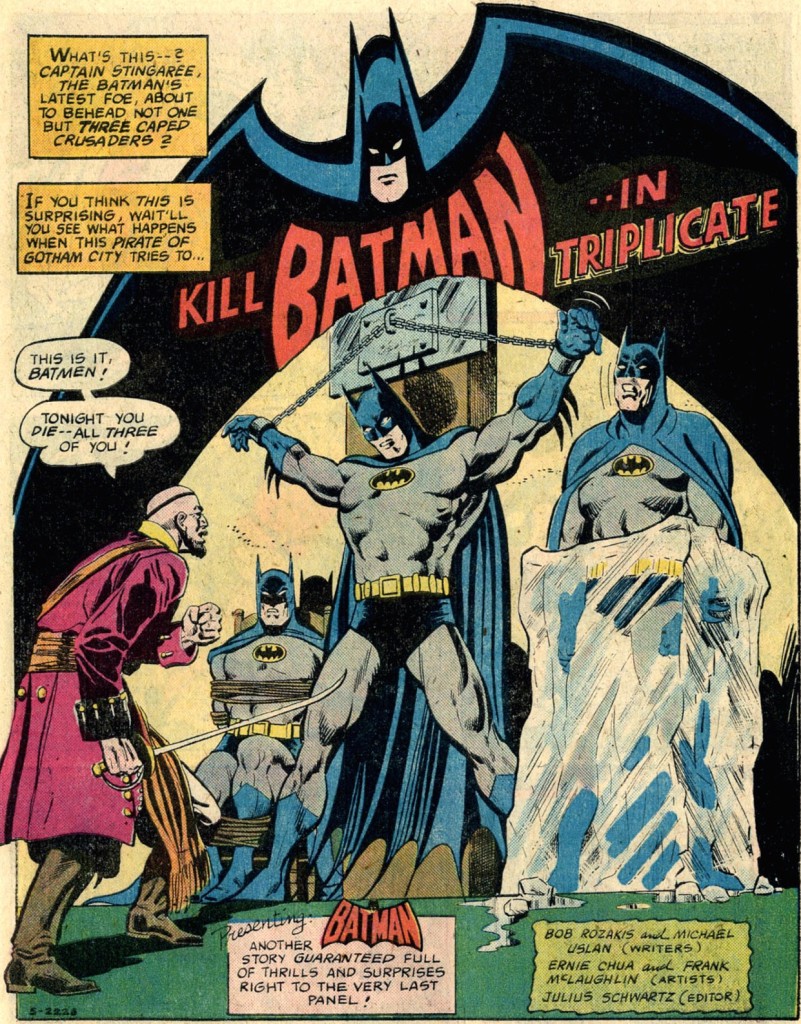

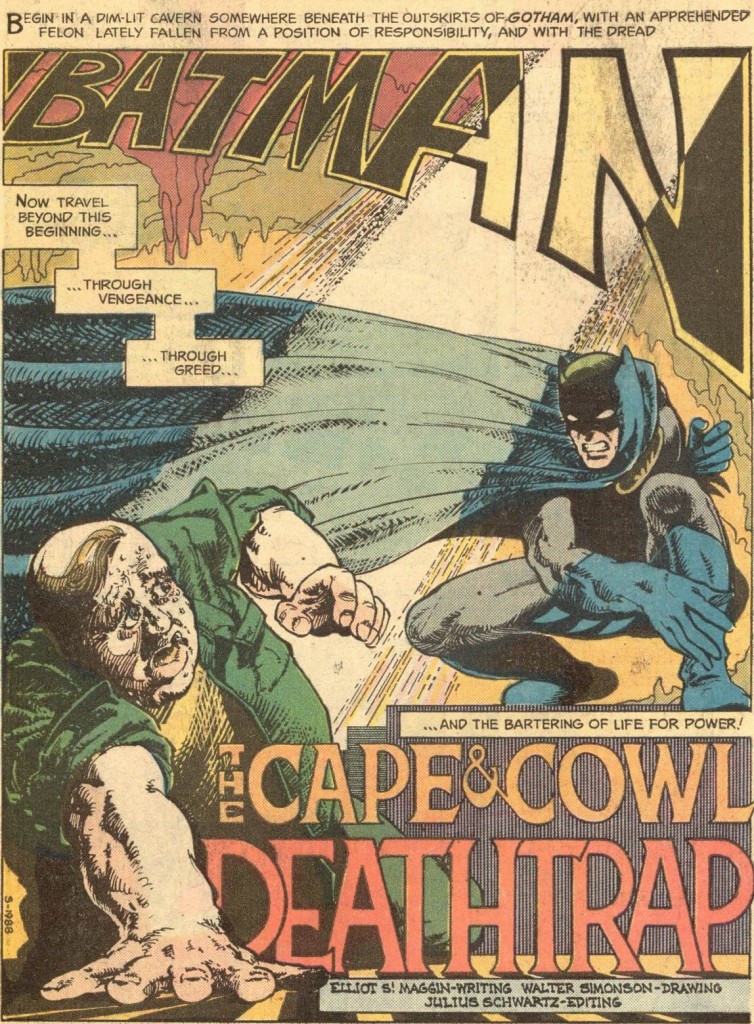

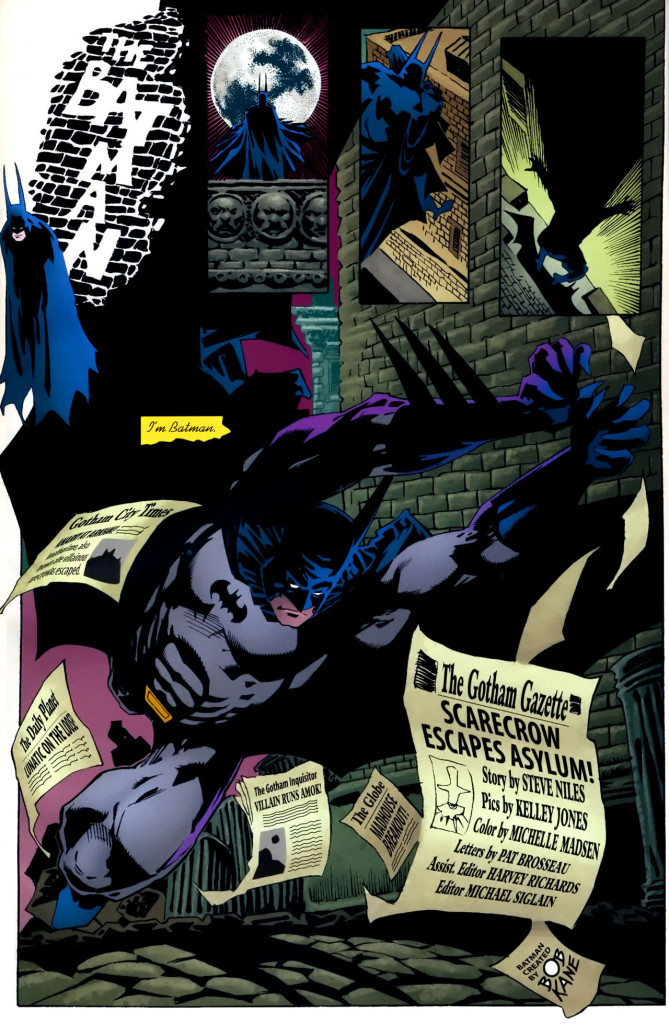

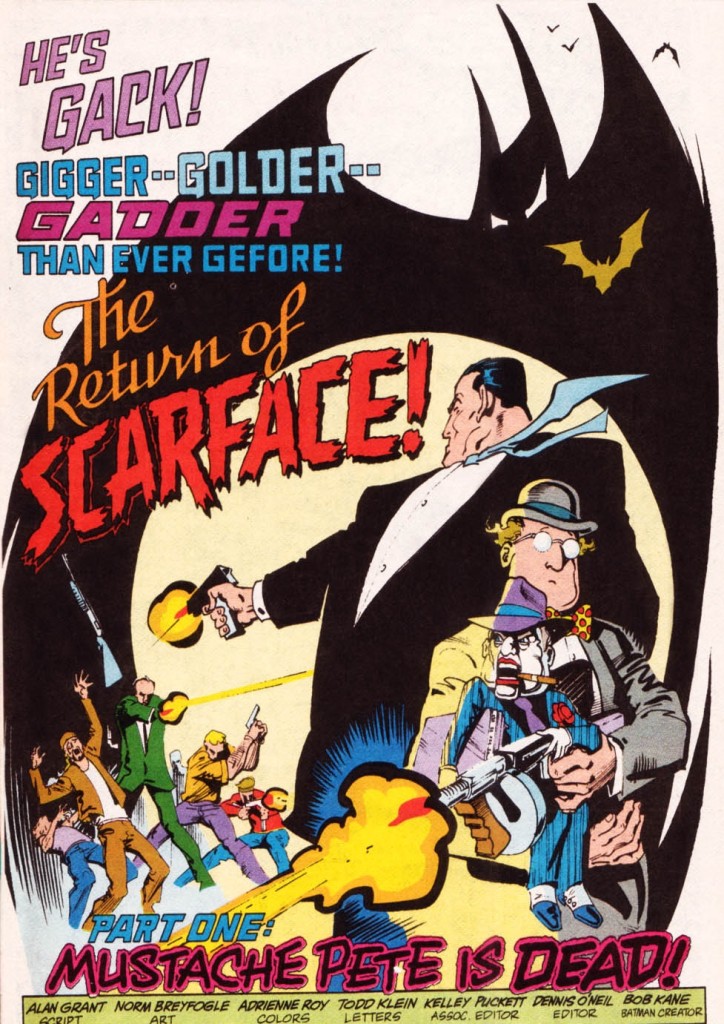

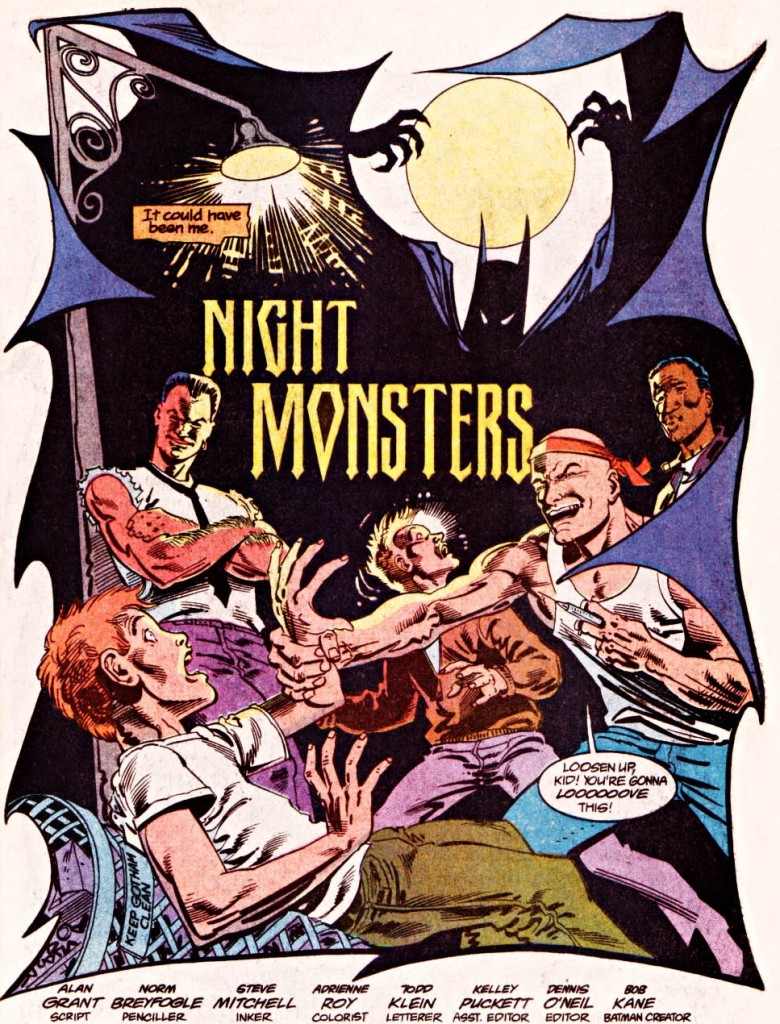

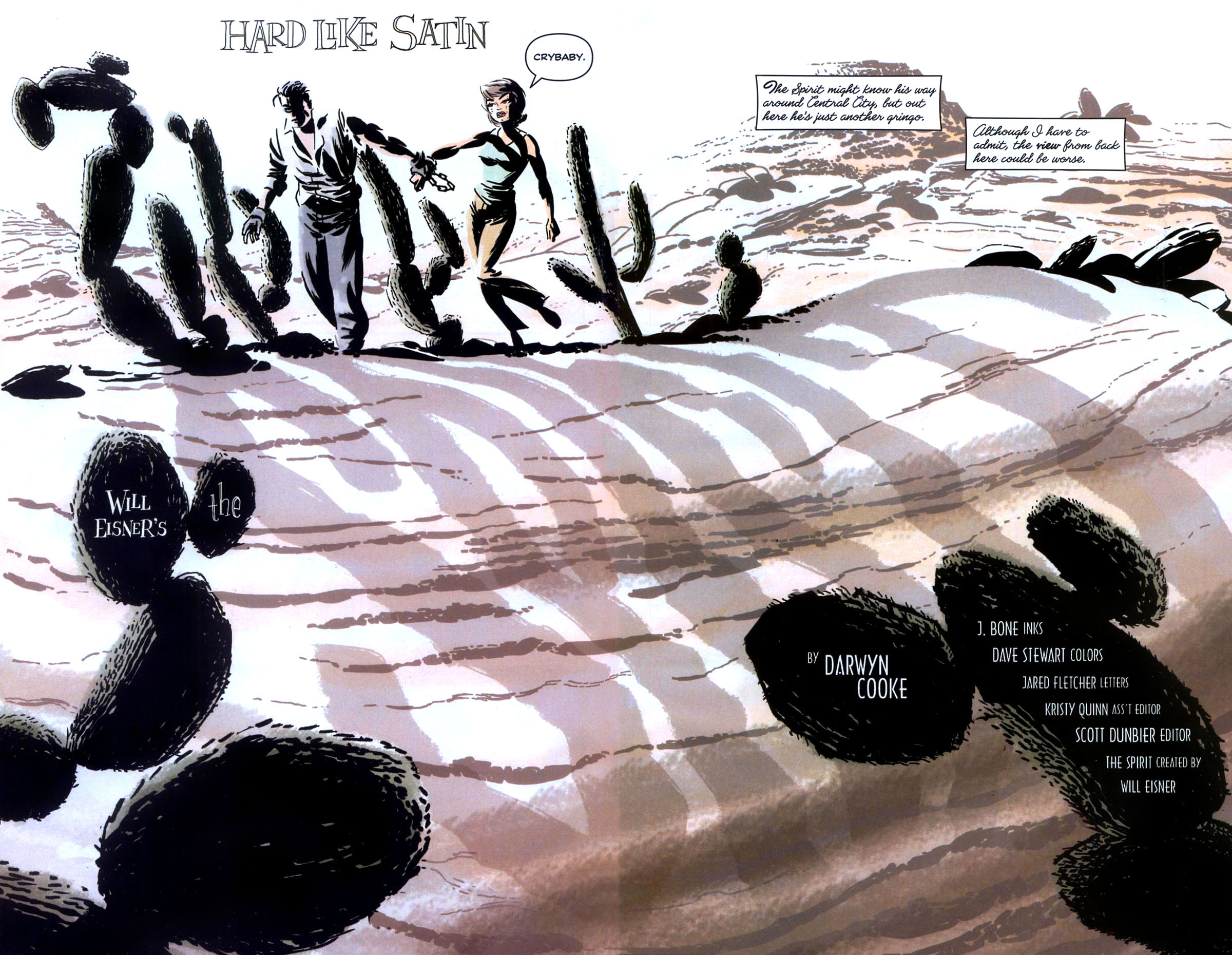

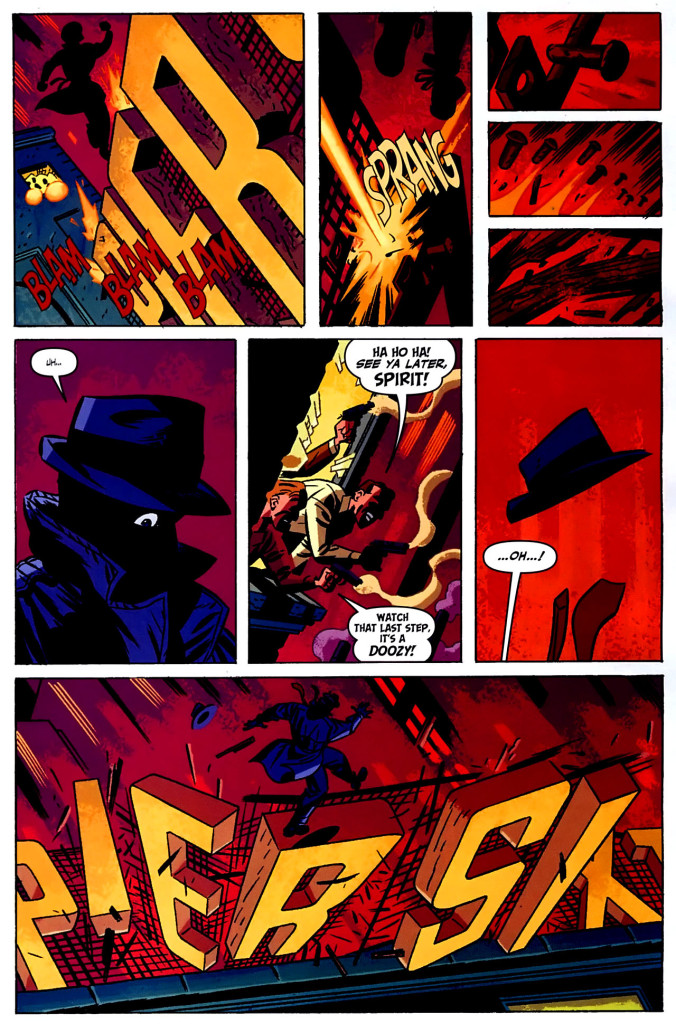

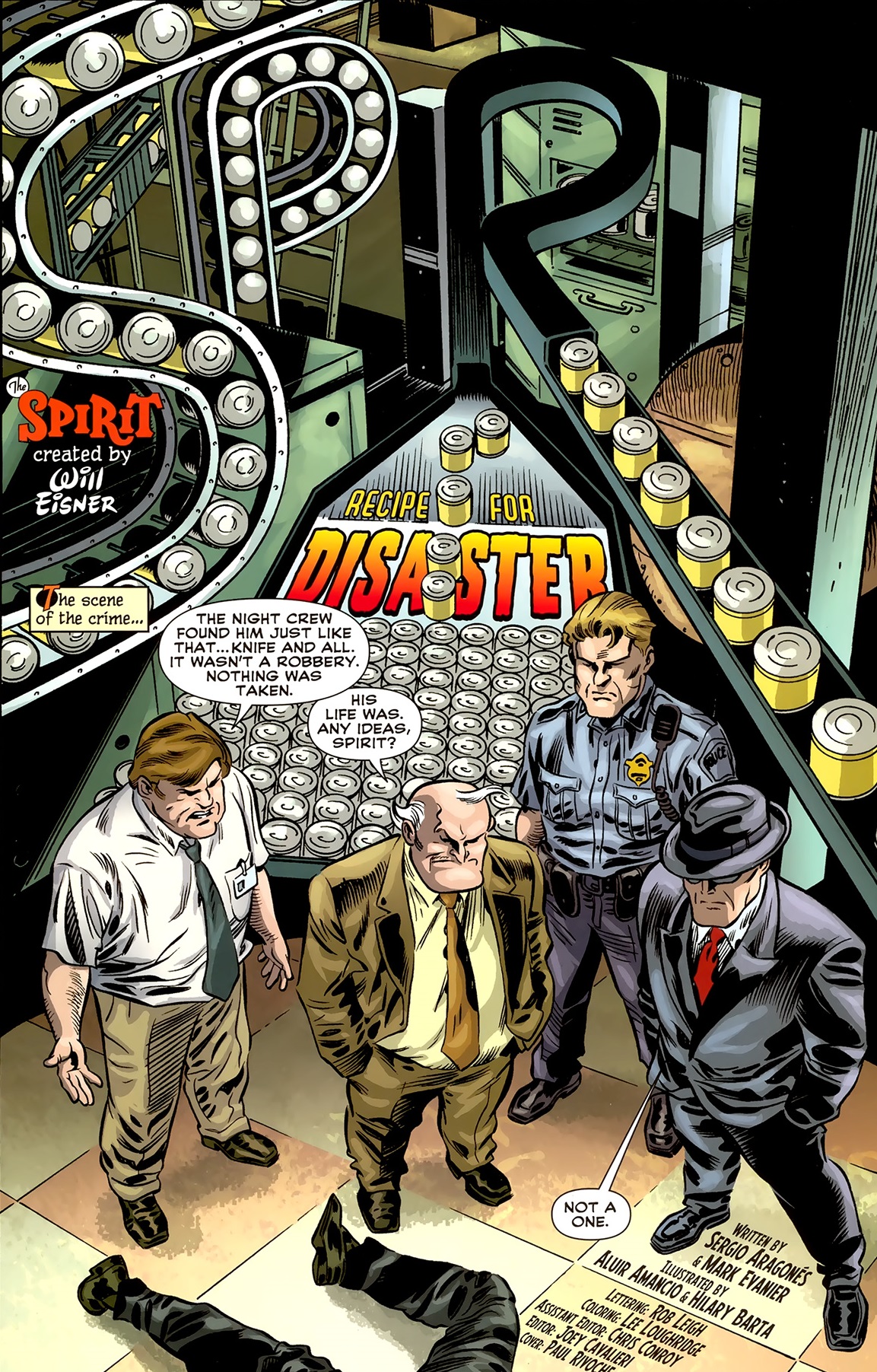

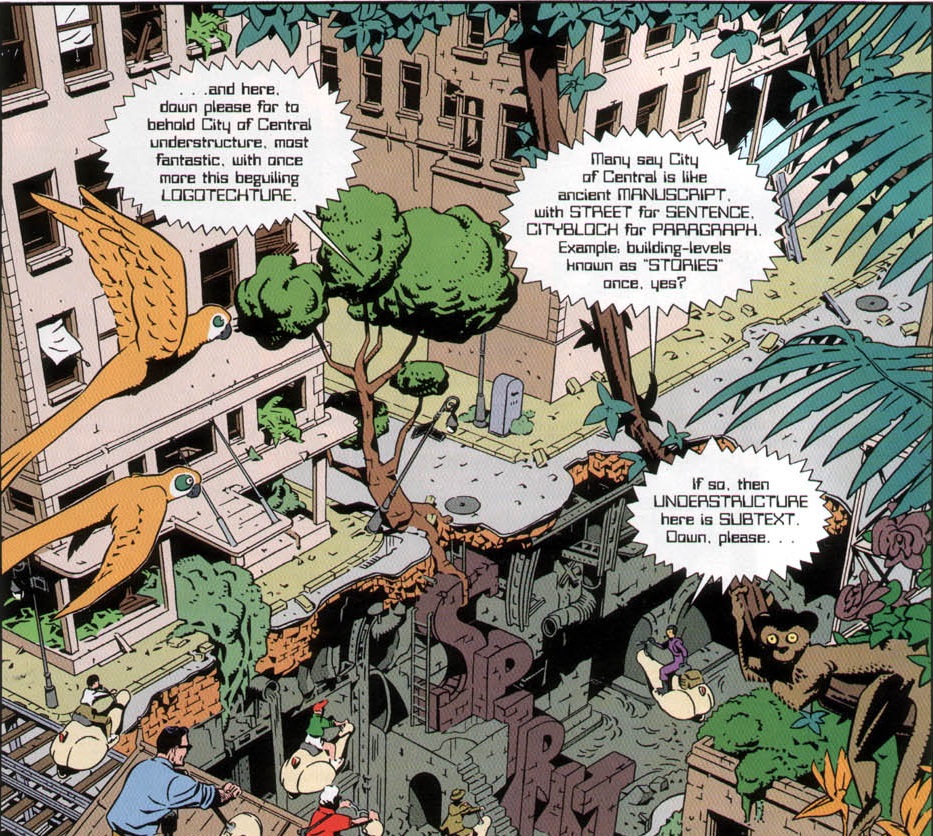

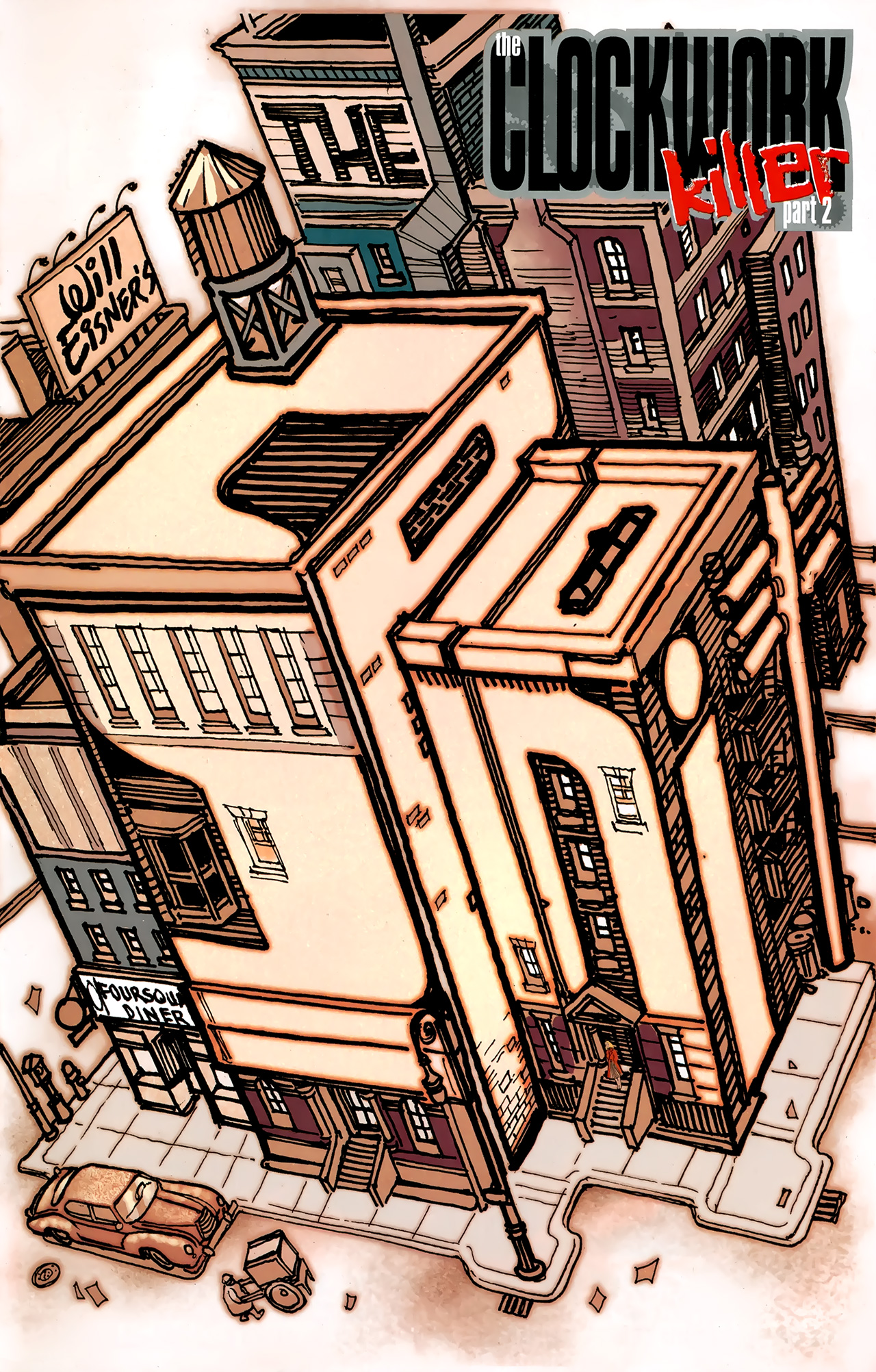

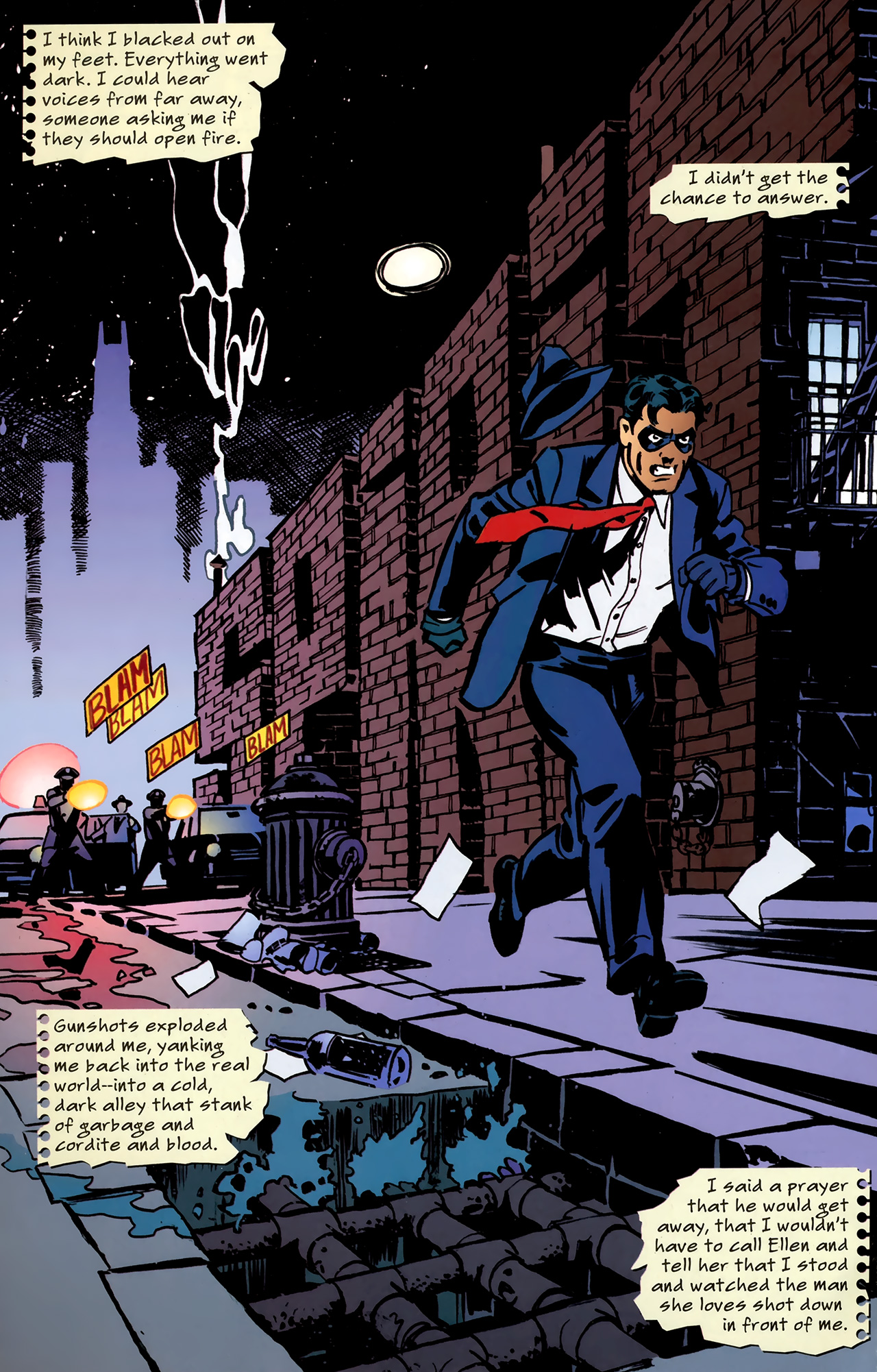

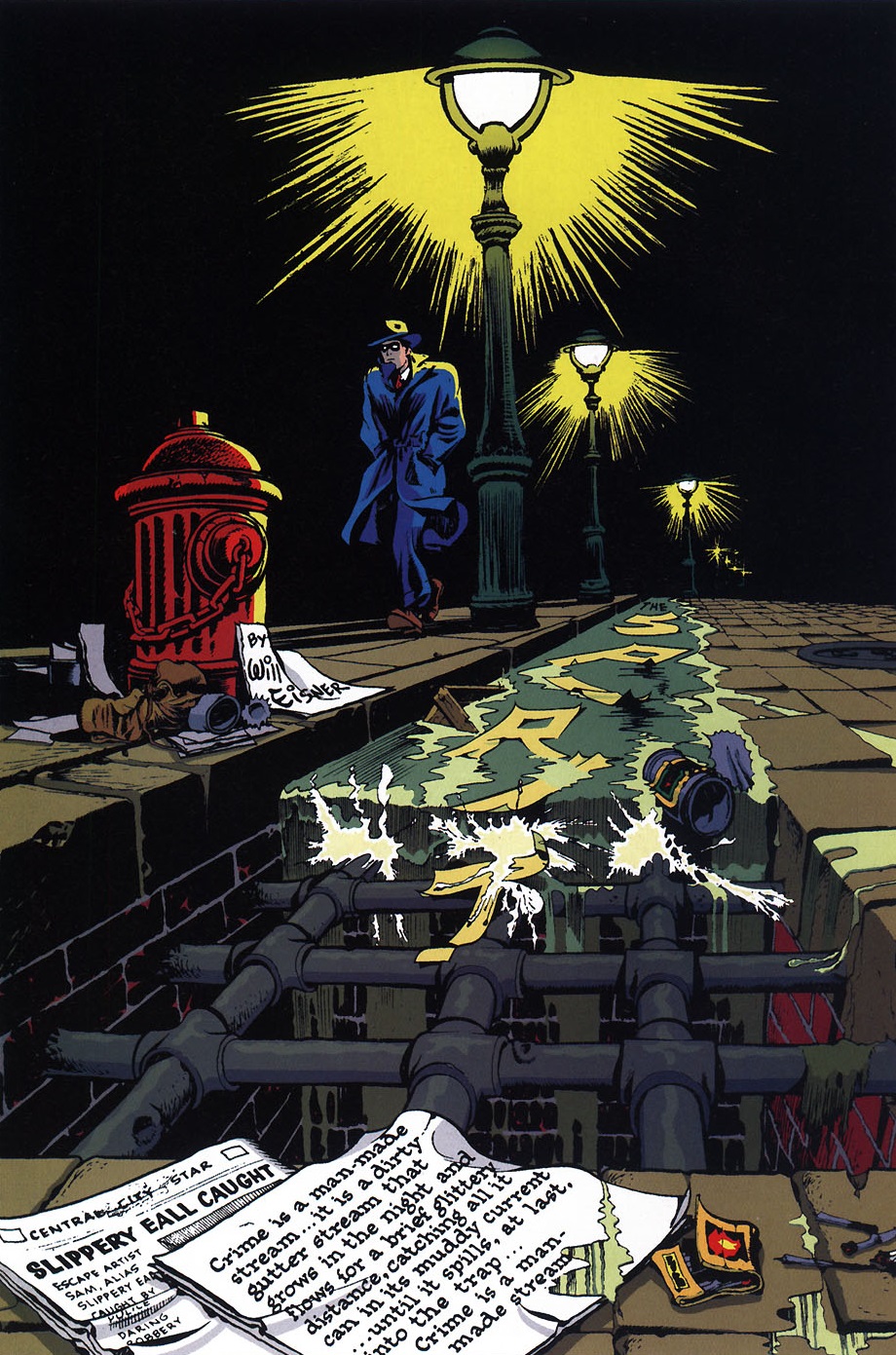

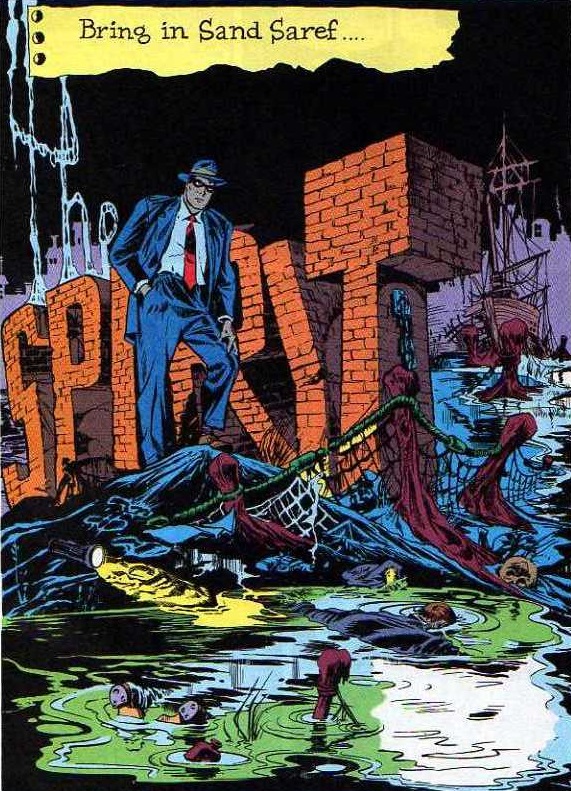

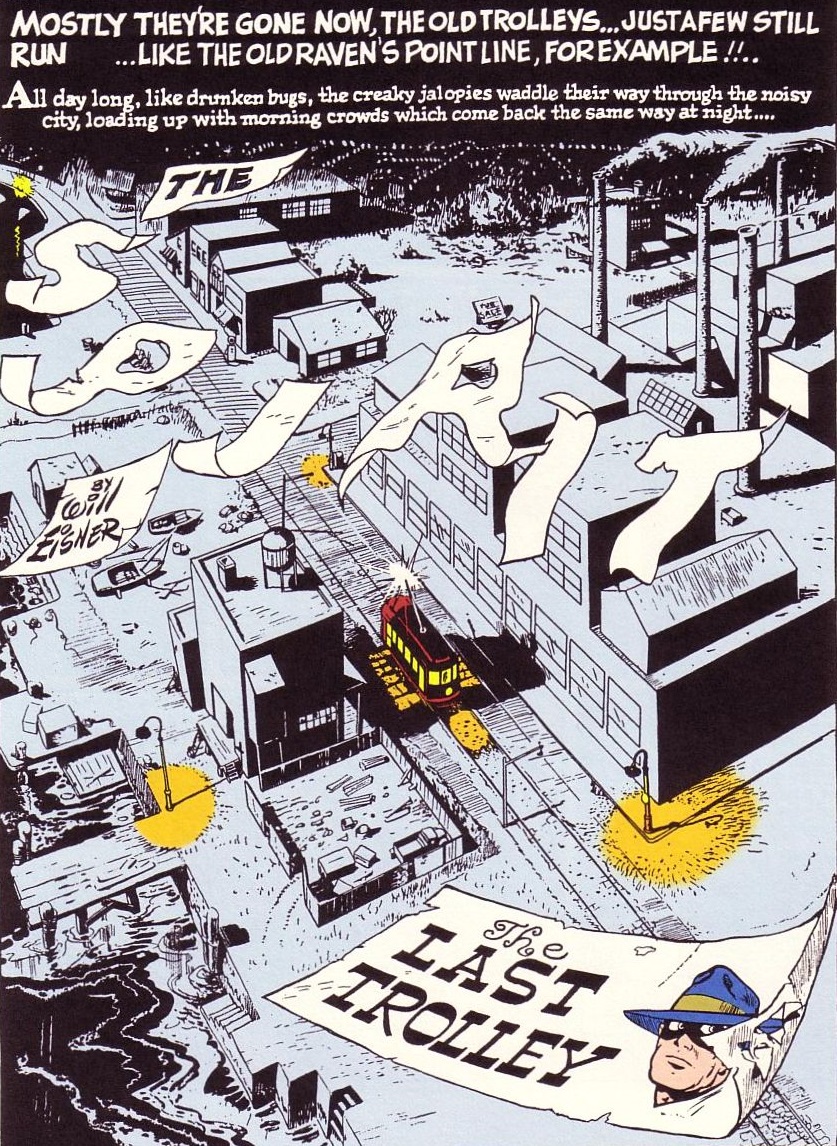

Legends of the Dark Knight #69-70: ‘Criminals’

Legends of the Dark Knight #71-73: ‘Werewolf’ (collected in Batman: Monsters)

Legends of the Dark Knight #74-75: ‘Engines’

Legends of the Dark Knight #76-78: ‘The Sleeping’ (collected in Other Realms)

Legends of the Dark Knight #79: ‘Favorite Things’ (collected in Batman: The Greatest Stories Ever Told)

Legends of the Dark Knight #80-82: ‘Idols’

Legends of the Dark Knight #83-84: ‘Infected’ (collected in Batman: Monsters)

Legends of the Dark Knight #85: ‘Citadel’

Legends of the Dark Knight #86-88: ‘Conspiracy’ (collected as Conspiracy and in Tales of the Batman: J.H. Williams III)

Legends of the Dark Knight #91-93: ‘Freakout’

Legends of the Dark Knight #95-97: ‘Dirty Tricks’

Legends of the Dark Knight #98-99: ‘Steps’

Legends of the Dark Knight Annual #1: ‘I Am a Gun’

Legends of the Dark Knight #102-104: ‘Spook’

Legends of the Dark Knight #105-106: ‘Duty’ [Introduces Sgt. Harvey Bullock.]

Legends of the Dark Knight #107-108: ‘Stalking’

Legends of the Dark Knight #109-111: ‘The Primal Riddle’ (collected in Tales of the Batman: Steve Englehart)

Legends of the Dark Knight #112-113: ‘Shipwreck’

Legends of the Dark Knight #115: ‘The Darkness’

Legends of the Dark Knight #28-30: ‘Faces’ (collected in Batman: Faces) [Opens with Two-Face’s escape and the rest is set two years later, while he’s still on the loose.]

Legends of the Dark Knight #31: ‘Family’ [It has been over three years since Alfred has taken a day off.]

THE CORLORFUL ERA [Although these comics certainly don’t lack tension and hard-hitting action, this intermediary era – organized around the debut of Batman’s first sidekicks – depicts the modern version of the more upbeat, devil-may-care ‘good old days’ to which characters will sometimes allude in the ’90s (even if, metatextually, their creators are actually referencing the pre-Crisis Silver Age). Again, there are other versions of these stories, but I think these fit in better with 1990s’ continuity.]

Legends of the Dark Knight #159-161: ‘Loyalties’ [Introduces James Gordon’s niece, Barbara, into the picture. (Published in 2002, but it fits nicely around here.)]

Robin Annual #4: ‘The Flying Graysons’ [The debut of the first Robin, Dick Grayson]

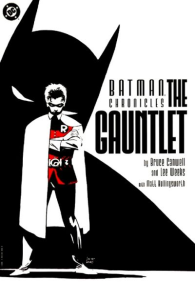

Batman Chronicles: The Gauntlet [Several later comics contain callbacks to this story of Robin’s first big test.]

Robin: Year One #1-4 (collected as Robin: Year One and in Batgirl/Robin: Year One) [First clashes with the Mad Hatter, Blockbuster, Killer Moth, Mr. Freeze, and Shrike (published in 2000, but clearly written by Chuck Dixon to fit with his work in the previous decade)]

Batgirl: Year One #1-9 (collected as Batgirl: Year One and in Batgirl/Robin: Year One) [The debut of the first Batgirl, Barbara Gordon, also retroactively introduces Jason Bard, Firefly, and Condiment King. Barbara’s adoptive father, James Gordon, becomes police commissioner.]

Legends of the Dark Knight #38: ‘Legend of the Dark Mite’ (collected in Collected Legends of the Dark Knight) [Introduces Bat-Mite]

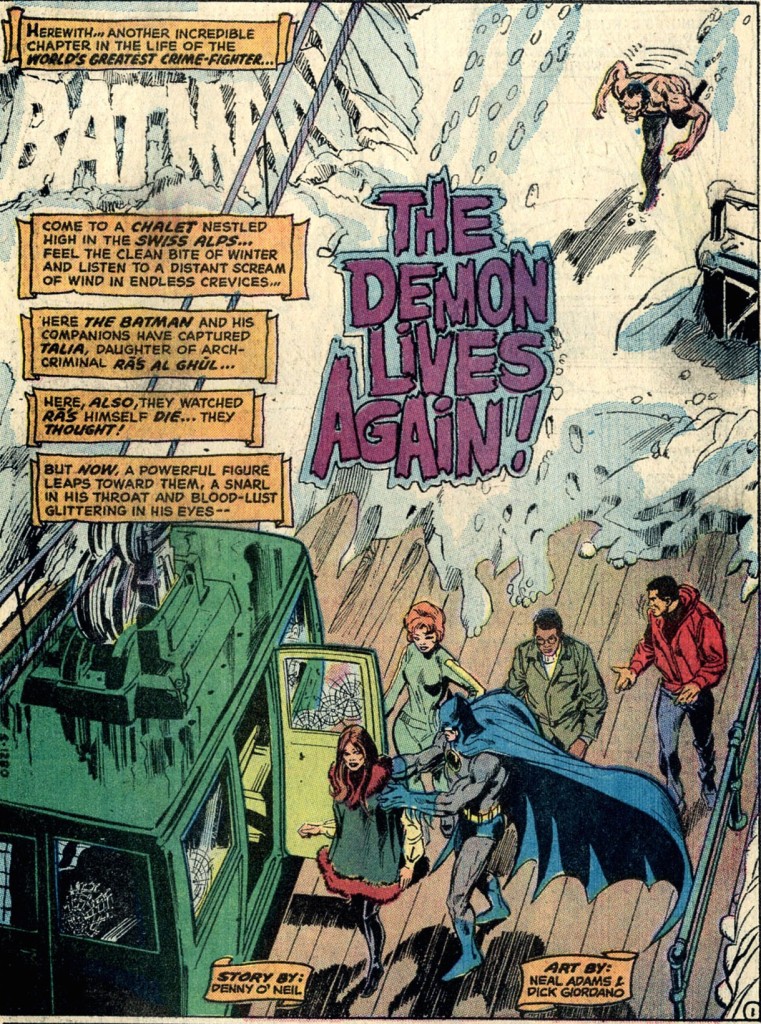

Tales of the Demon [This book collects the pre-Crisis tales that introduced Talia and Ra’s al Ghul (as well as Matches Malone). Those comics were such classics that nobody dared remake them in the ‘90s, so they remain an advisable read for anyone interested in Batman’s early encounters with the al Ghul clan (or just for anyone interested in kickass adventure yarns). Completists may first want to check out Detective Comics #405-406, which lead into the first of the stories collected here.]

Detective Comics #484: ‘Assault on Olympus!’ (collected in Tales of the Batman: Don Newton) [Similarly, since there is no post-Crisis tale about the first direct clash between Batman and Zeus, some of you may wish to check out this pre-Crisis version. (Technically, the two characters had an earlier (more indirect) confrontation in the previous issue, but that one is a very pre-Crisis story, while this one can be retrofitted into post-Crisis continuity without great leaps of imagination.)]

Nightwing #101-106: ‘Nightwing: Year One’ (collected as Nightwing: Year One) [Although it came out in 2005, this retconned version of Dick Grayson’s debut as Nightwing and Jason Todd’s debut as the second Robin was done by the same team who did Nightwing in the ‘90s, so it feels ‘truer’ to that series. (Also, there are so many nods to Robin: Year One and Batgirl: Year One that it’s nice to have those fresh in your mind while reading this one.)]

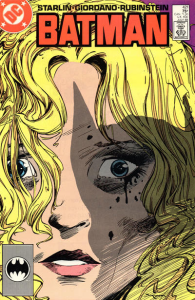

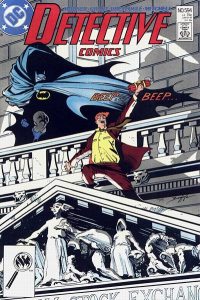

THE DARK ERA [The late 1980s’ depressing tone isn’t quite what we’ll find in the ‘90s, but this era introduces several characters and plot points that will play a role later on. Bear in mind that, if the previous eras were set in some undefined, ‘legendary’ time (with some contradictory aesthetics and technology levels), we are now clearly in the final years of the Cold War. Because the continuity isn’t very tight yet, I’ve mostly separated the comics into blocks, rather than listing every single issue.]

Batman #386-387/Detective Comics #553: ‘Black Mask: Losing Face/The False Face Society of Gotham/Ebon Masquery’ (collected in Arkham: Black Mask) [Although these are pre-Crisis comics, Doug Moench will stick to this origin of Black Mask and Circe when he brings those characters back, in Batman #484-485.]

Batman #393-394: ‘The Dark Rider/At the Heart of Stone’ [The same goes for this pre-Crisis introduction of Dark Rider, who will return in 1995’s ‘Troika’ arc.]

Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth [Grant Morrison’s and Dave McKean’s acclaimed graphic novel feels more like a nightmare than like an in-continuity tale, but it does introduce Amadeus Arkham, whose nephew will take over the titular asylum in the ‘90s. We learn about the institution’s backstory.]

The Killing Joke (collected in DC Universe: The Stories of Alan Moore) [Alan Moore’s and Brian Bolland’s classic tale sets up the Joker’s and Barbara Gordon’s dynamics for years to come.]

The Question #1-36 (collected in a series of volumes, starting with The Question, v1: Zen and Violence) [Although not set in Gotham City, Denny O’Neil’s and Denys Cowan’s cult run introduced a few characters that found their way into Batman comics, like the mechanical genius Harold, who ended up working in the Batcave for much of the ‘90s.]

Detective Comics Annual #1/Green Arrow Annual #1/The Question Annual #1: ‘Fables’ (‘The Monkey Trap/Lesson for a Crab/The Silent Parable;’ the first story (starring Batman) was collected in The Dark Knight Detective, v2) [In this nifty crossover penned by Denny O’Neil and set sometime after The Question #18, Batman meets Lady Shiva. In a similar stunt, O’Neil’s The Question Annual #2 and Green Arrow Annual #2 are also connected (and best read between #30 and #31).]

Cosmic Odyssey #1-4 (collected as Cosmic Odyssey) [A great superhero space adventure by Jim Starlin and Mike Mignola where Batman plays a key role, as do the Gotham-based demonologist Jason Blood and the demon Etrigan (who had been separated in Matt Wagner’s 1987 Demon mini-series).]

Secret Origins #44: ‘The Coming of Clayface/The Tragic Though Amusing History of Clayface II/His Name is Clayface III’ (collected in Arkham: Clayface) [The origins of different characters to go by the name of Clayface.]

Batman #414-430 (the early issues collected in Second Chances, the middle ones in The Caped Crusader, v1, and the later ones in A Death in the Family) [Jim Starlin’s and Jim Aparo’s ultra-gritty run presents the downward spiral of the second Robin, which will remain in the back of Batman’s mind throughout the upcoming decade. In terms of strict continuity, the most significant arcs are ‘Ten Nights of the Beast’ (#417-420, the KGBeast’s debut) and ‘A Death in the Family’ (#426-429, Jason Todd’s death).]

Secret Origins Special #1 (collected in Featuring Two-Face and the Riddler and Whatever Happened to the Caped Crusader?) [The framing device (by Neil Gaiman and Mike Hoffman) for this venture into the origins of the Penguin, Riddler, and Two-Face revolves around the production of a documentary film, set in the aftermath of ‘A Death in the Family’ (because the Joker is still missing).]

Batman #431-435 (collected in The Caped Crusader, v2) [These tales written by James Owsley (now Christopher Priest) and John Byrne, with art by Jim Aparo, feel like neat epilogues to Aparo’s run with Starlin, showcasing Batman’s mood after Robin’s death.]

Batman Annual #13: ‘Faces/Waiting in the Wings’ (collected in The Caped Crusader, v2; ‘Waiting in the Wings’ also in Batman Allies: Alfred Pennyworth) [Also written by Jim Owsley, this issue sets up Two-Face’s latest status quo.]

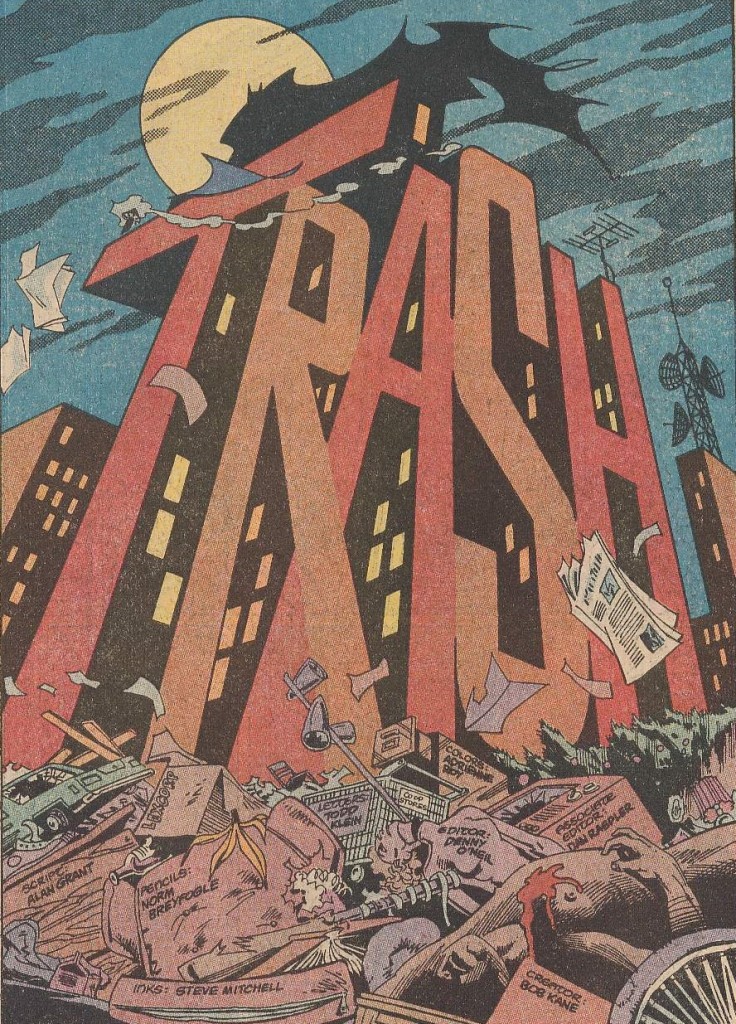

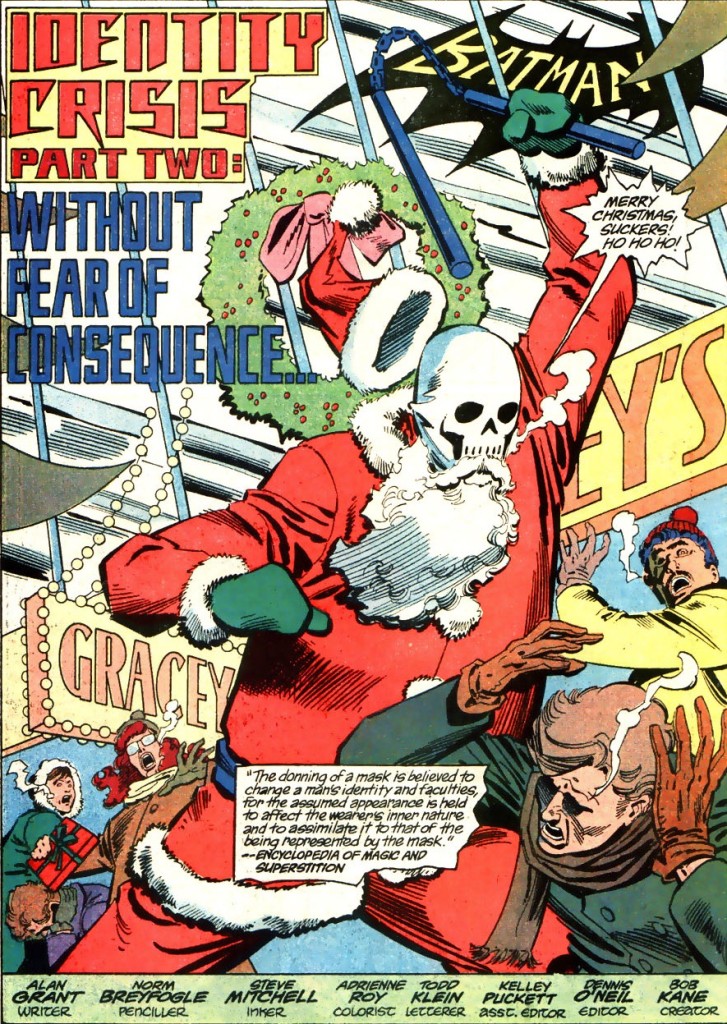

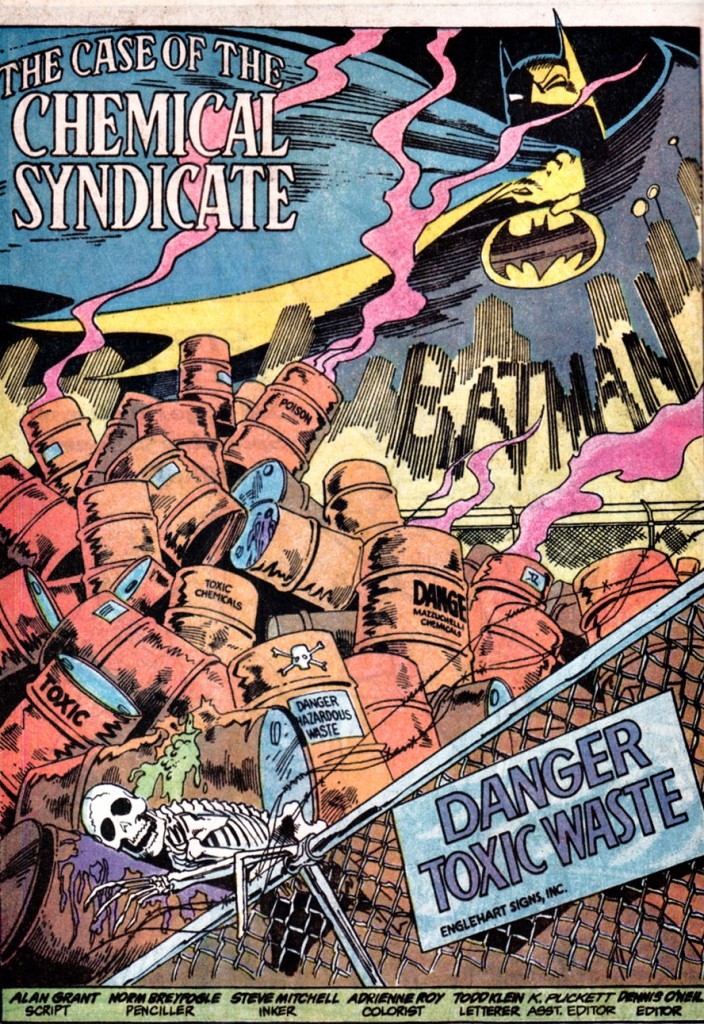

Detective Comics #583-597, 601-611 (most issues collected in The Dark Knight Detective, v2 & v3 and Legends of the Dark Knight: Norm Breyfogle, v1 & v2) [Alan Grant’s and Norm Breyfogle’s run in Detective Comics includes the debuts of the Ventriloquist/Scarface, Ratcatcher, Corrosive Man, Mortimer Kadaver, Cornelius Stirk, Joe Potato, and Anarky. Breyfogle didn’t draw #595 (part of the larger DC crossover Invasion) and #596-597 (which introduced GCPD detective Stan Kitch). Neither creator was involved in #598-600 (the dispensable ‘Blind Justice’ interlude). Batman operates alone in these stories, so they may be set anytime before, during, or after the other ones on this section, except for the arc with Etrigan/Jason Blood (‘Tulpa,’ #601-603), explicitly set after Cosmic Odyssey, and the Clayface arc (‘The Mud Pack,’ #604-607), which has to take place after Jason Todd’s death.]

Son of the Demon (collected in Batman: Birth of the Demon) [This controversial graphic novel presents an epic adventure that works as the culmination of the saga depicted in the Tales of the Demon collection.]

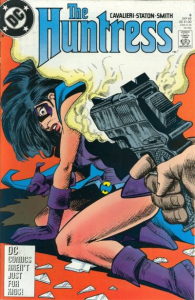

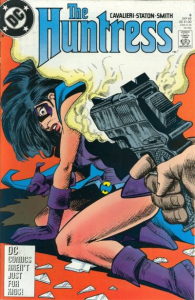

The Huntress #1-19 [This 1989 series by Joey Cavalieri and Joe Staton chronicles the rebooted origin of the Huntress that informed the comics of the ‘90s.]

While it’s not set in Gotham City, I also suggest checking out John Ostrander’s, Kim Yale’s, and Luke McDonnell’s Suicide Squad (an awesome adventure series about super-criminals going on risky missions in exchange for penalty reduction, collected in a series of volumes, starting with Suicide Squad, v1: Trial by Fire), which features plenty of guest-appearances by the Dark Knight and his rogues’ gallery. It takes place after The Killing Joke.

Hardcore completists may also be interested in tracking down Alan Grant’s and Mark Pacella’s The Demon strip, which ran in Action Comics Weekly #636-641 and takes place after Detective Comics #601-603. This horror fantasy strip about Etrigan and Jason Blood ended in a cliffhanger which was picked up a year later in a new, largely Gotham-set Demon series (also written by Grant).

Finally, even though it came out later, I’d say the first (and very cool) Batman versus Predator mini-series (collected in paperback) also belongs here, as it probably takes place before the third Robin, Tim Drake, enters the scene.

Part 2 of this series of posts will follow in two weeks!