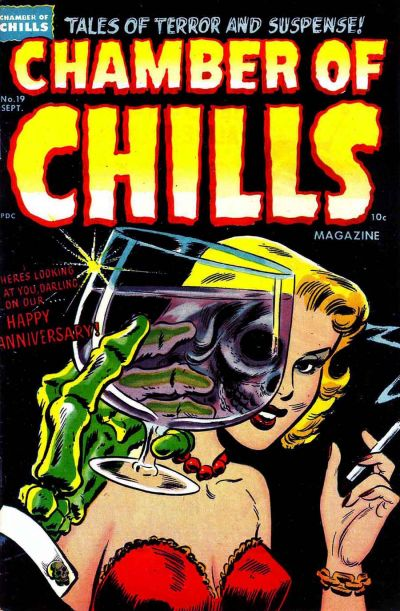

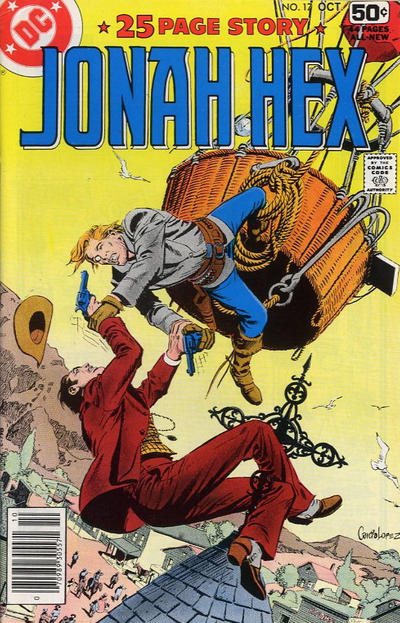

With his propensity for heady digressions, offbeat satire, and countercultural sensibility, Steve Gerber was one of the most fascinating American writers in mainstream comics. While he didn’t exactly deconstruct superheroes in the radical form that some of his successors would do, throughout his career Gerber often sneaked in subversive, thought-provoking ideas that emphasized the material’s inherent strangeness and metaphorical potential, including in a number of twisted Superman stories. When I say ‘twisted,’ I don’t just mean in the sense that Gerber did dark and disturbing comics (although there were plenty of those as well), but also in the sense that he distorted this iconic hero’s mythos, coming up with suggestive, original spins on existing concepts.

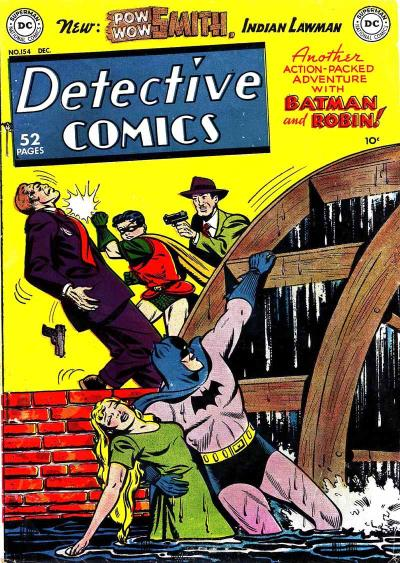

This trend went back to the early 1970s, years before Steve Gerber was even hired by DC Comics. During his cult run on Marvel’s swamp monster character Man-Thing, Gerber created – with artist Val Mayerick – his first twisted version of the Man of Steel in the form of a long-haired super-human alien orphan called Wundarr…

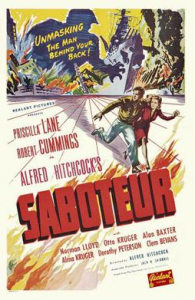

Fear #17

Fear #17

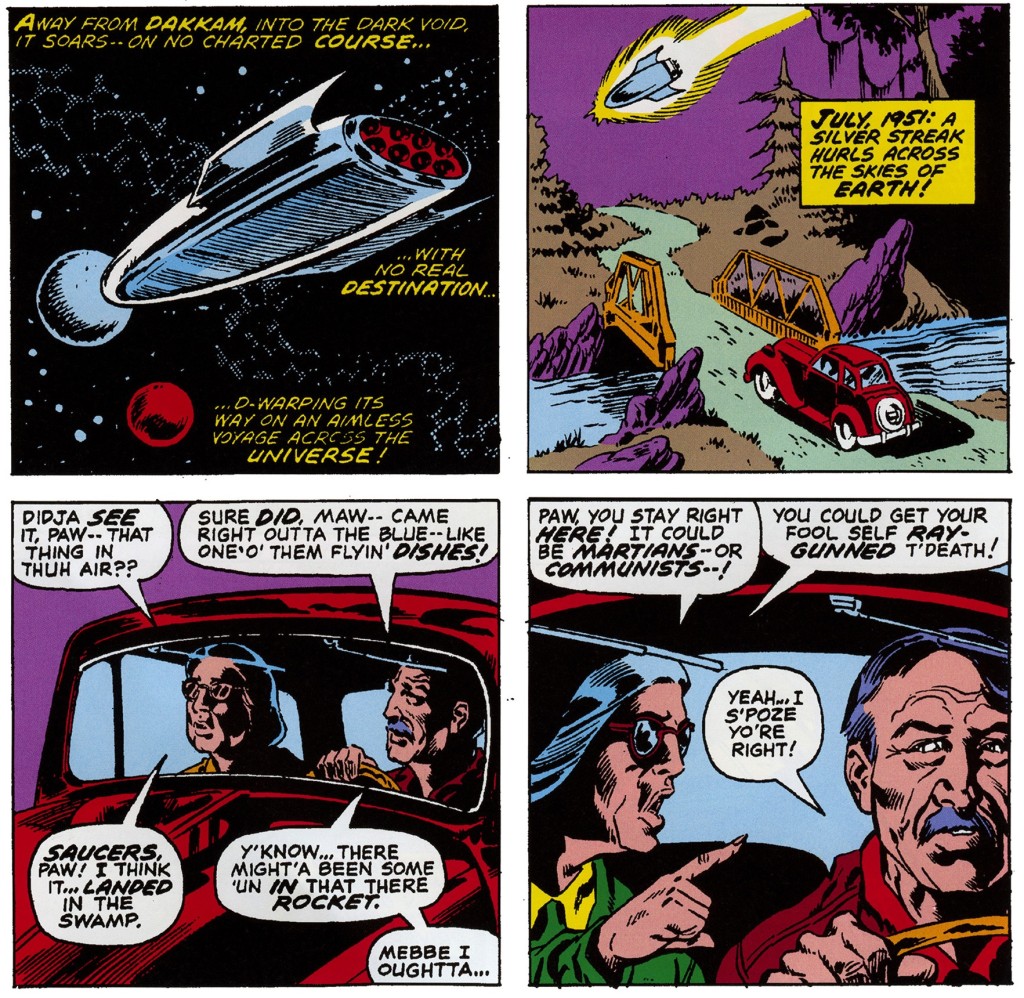

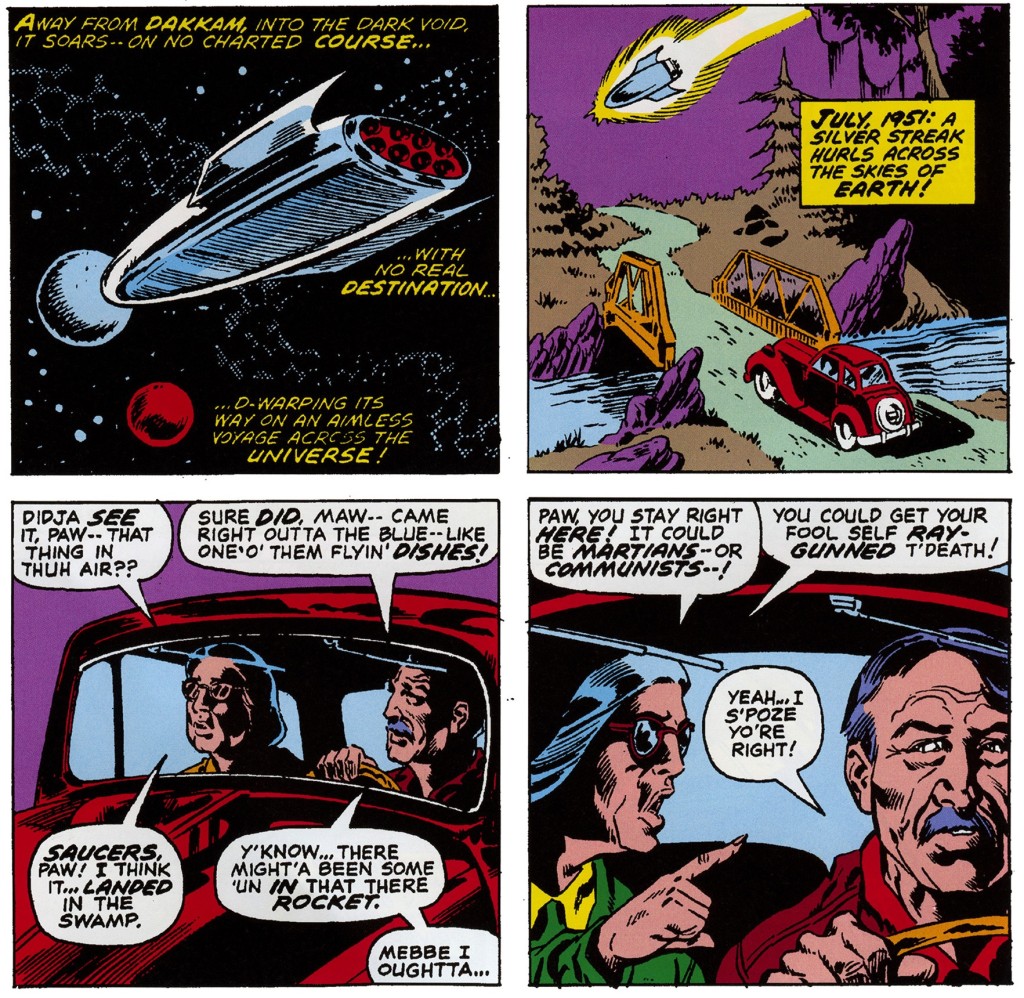

In ‘It Came Out of the Sky!’ (Fear #17, cover-dated October 1973), a flashback – clearly molded on Superman’s origin – revealed Wundarr to have been sent into outer space by his parents, after his father had failed to convince the rulers of the Krypton-like planet Dakkam that their sun was about to go nova. This sequence stayed relatively close to the original while allegorically framing the ersatz-Lara and Jor-El as persecuted young voices warning their elders against the dangers of ecological collapse and/or nuclear holocaust.

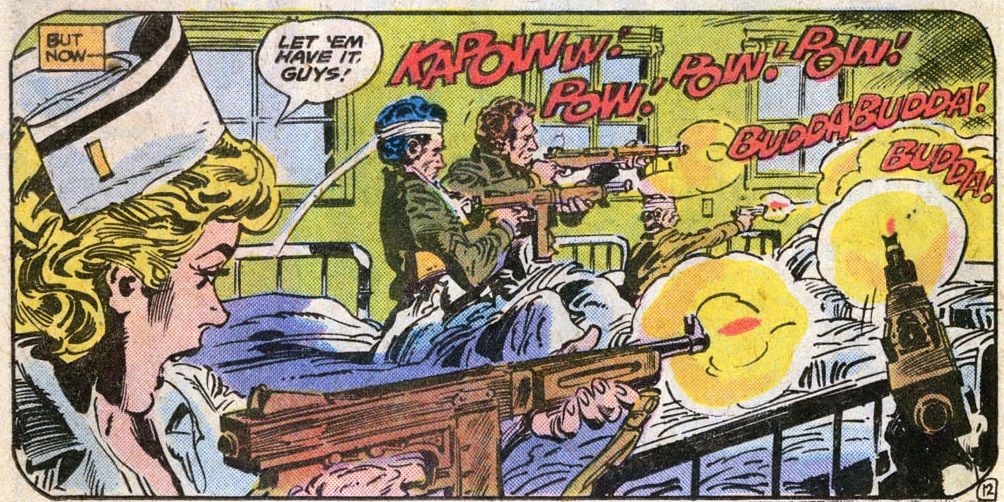

The big twist came when Wundarr’s spaceship crash-landed on Earth – because it did so in 1951, Superman’s familiar origin tale got sidetracked by that era’s paranoia:

Fear #17

Fear #17

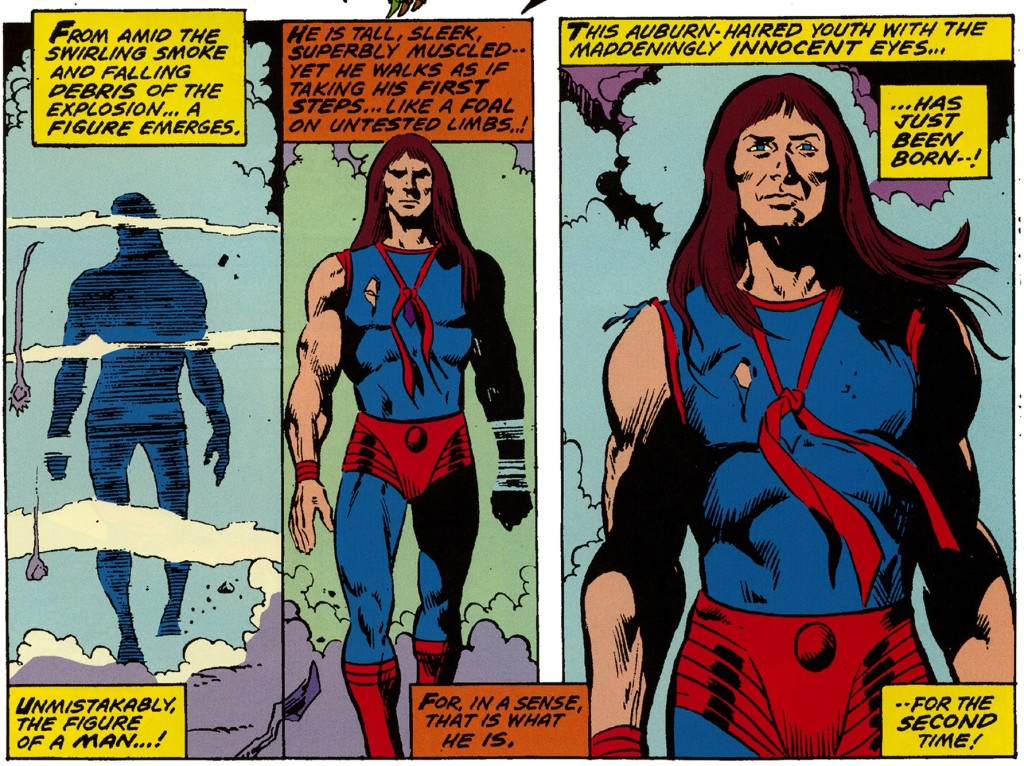

From here on, everything went off the rails… Without being rescued by a terrestrial couple, Wundarr remained in the rocket for twenty-two years, believing ‘the warm, womb-like interior of the spacecraft’ to be whole world and ‘believing himself to be the only living thing’ in the world… at least until an explosion finally burst open the ship. Still reeling from the shock, the first creature the child-like Wundarr saw was Man-Thing, so naturally he assumed the monster was his mother, which somehow lead to a destructive slugfest between the two in a nearby town. Despite the comedic undertones, this was first and foremost a horror comic – the horror here being the notion of ‘What if Superman was deranged?’ and ‘What if he had no moral qualms about collateral damage when fighting in populated areas?’ (the latter anticipating Zack Snyder’s 2013 blockbuster).

Apparently, DC didn’t appreciate the blatant parallel with its own hero and Stan Lee even considered firing Steve Gerber over this, but Marvel ended up keeping the character, albeit with enough changes to significantly distance him from the competition. Wundarr became a recurring player in Gerber’s run on Marvel Two-In-One, gaining a new suit and powers in the process, although at first being mostly defined by the fact that he possessed ‘the mind of an infant and the strength of an elephant.’ In his first appearance on that series, ‘Manhunters from the Stars!’ (issue #2, March 1974), a couple of aliens – and a robot assassin called Mortoid – arrived from Dakkam to kill Wundarr, only to find themselves baffled by his ‘rampant stupidity.’ The underlying joke was that Dakkam’s sun had not gone nova after all, thus making Wundarr’s saga an even more pathetic deviation from Superman’s official narrative!

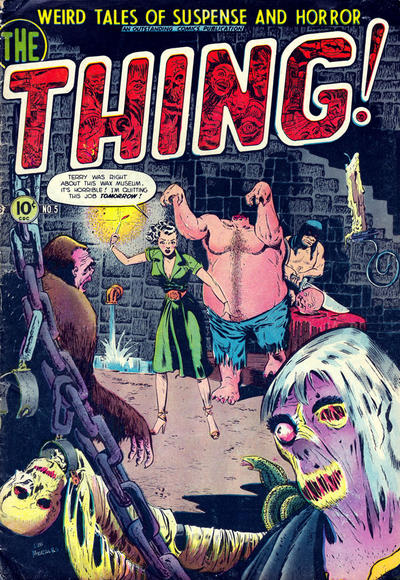

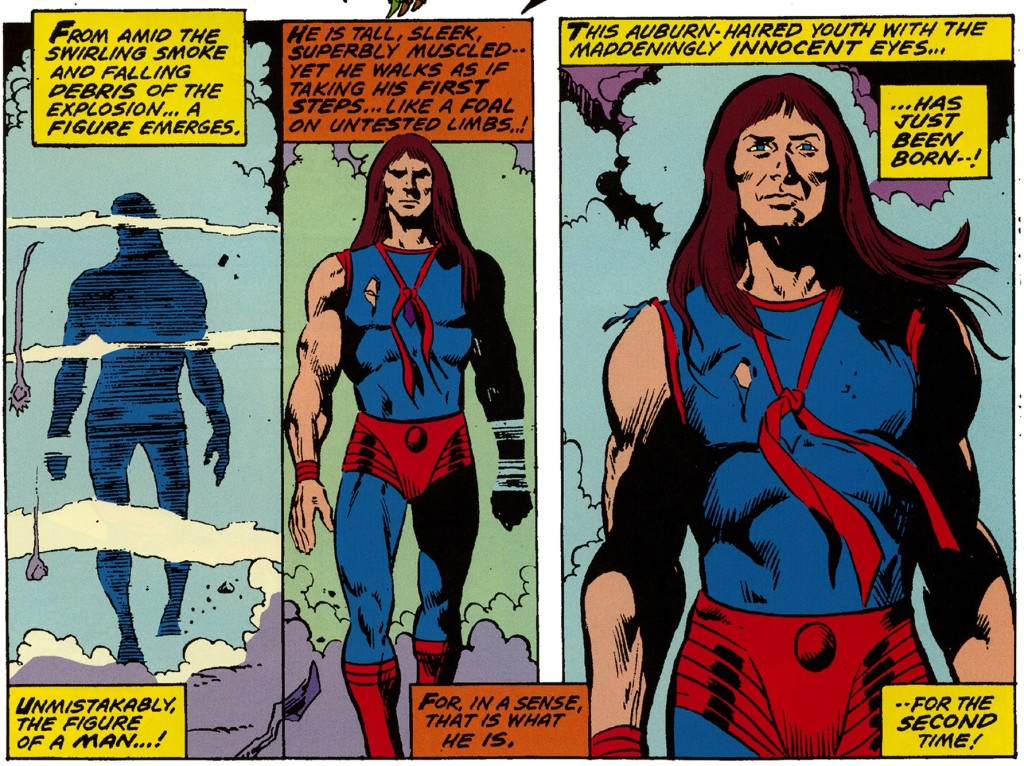

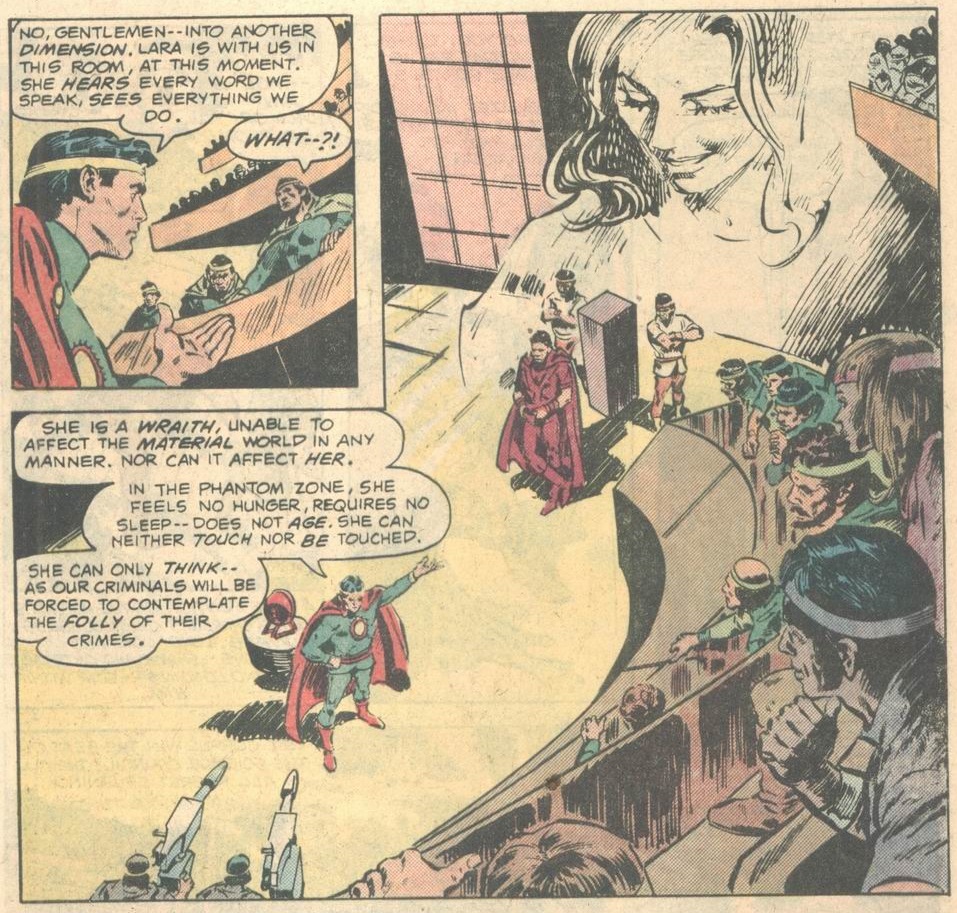

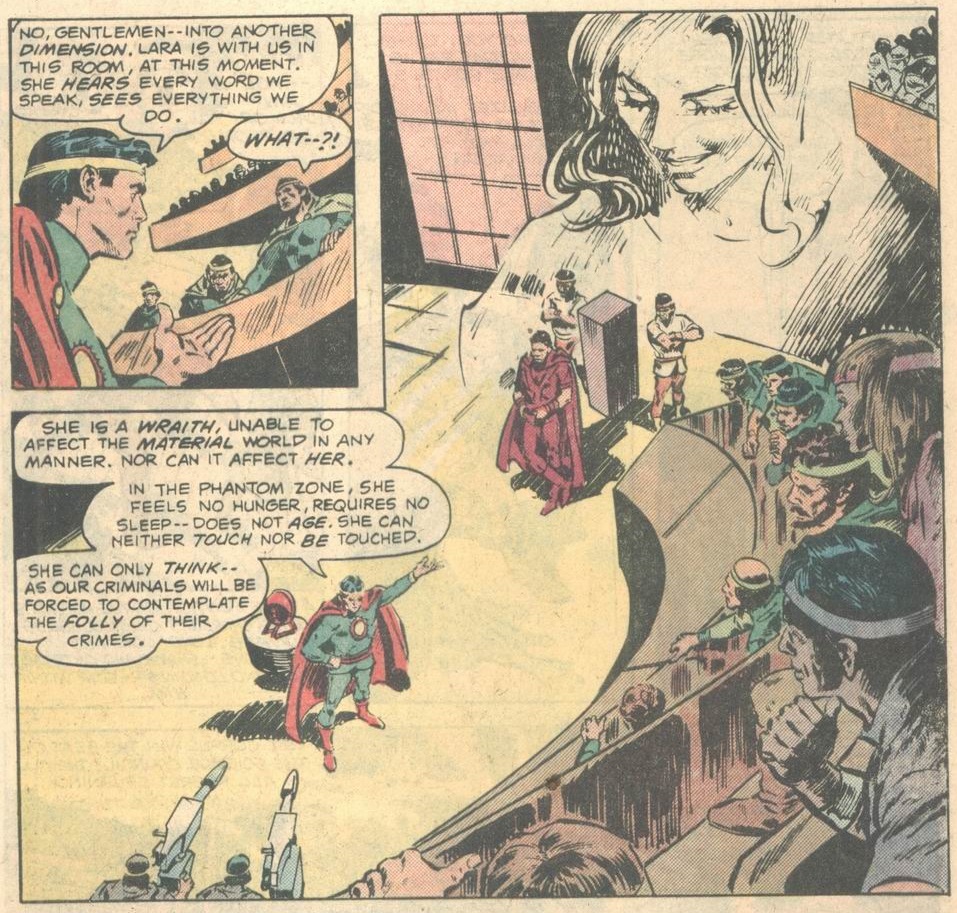

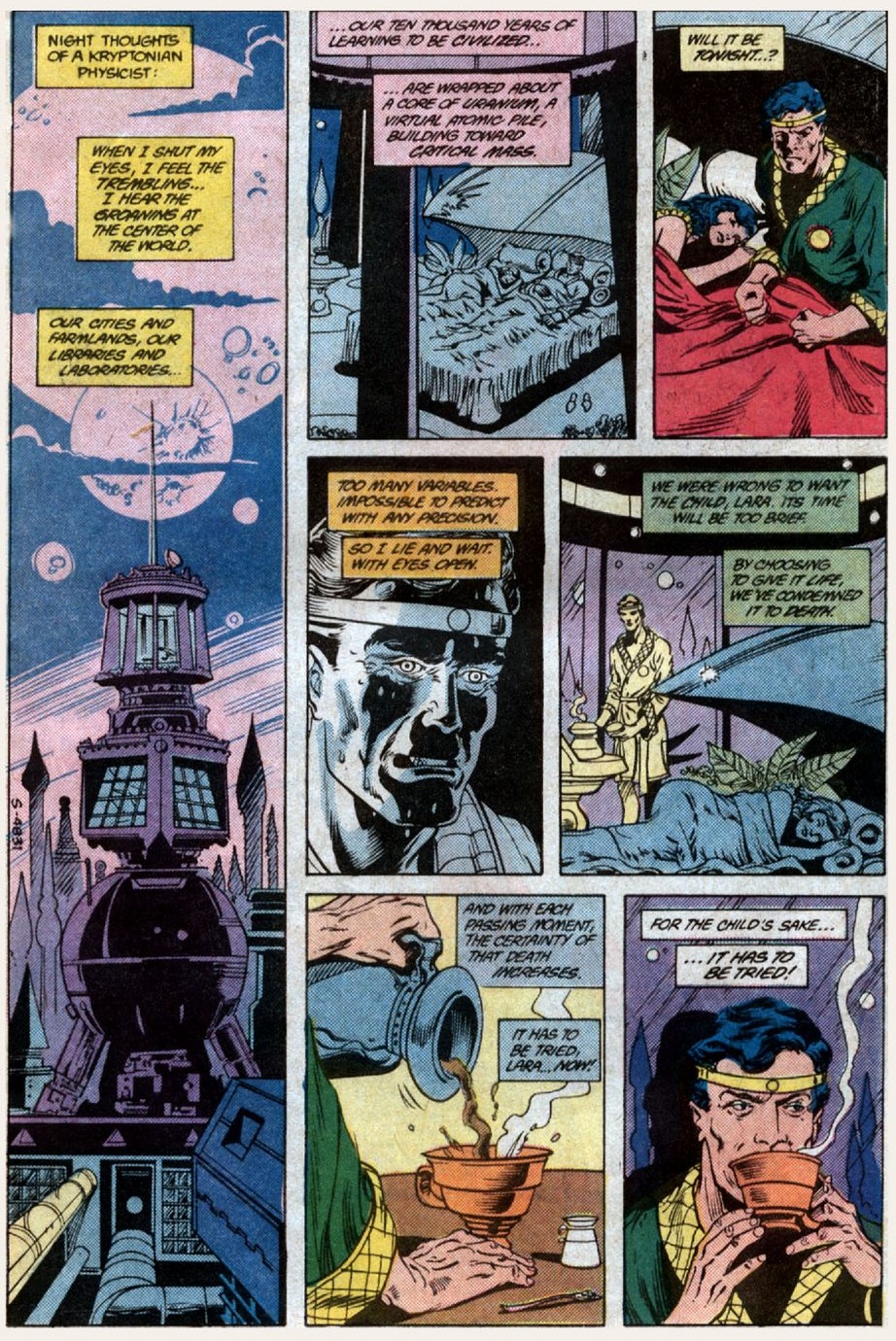

This mean-spirited caricature didn’t prevent DC from eventually hiring Steve Gerber to write the actual Man of Steel. His 1982 mini-series Phantom Zone built on one of the great Silver Age additions to Kyrptonian lore, namely the fact that Superman’s father, Jor-El, had used a ‘pocket universe’ outside the space-time continuum as a prison for super-criminals…

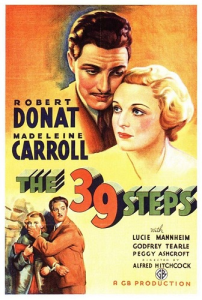

Phantom Zone #1

Phantom Zone #1

(Talk about cutting costs on the prison system…)

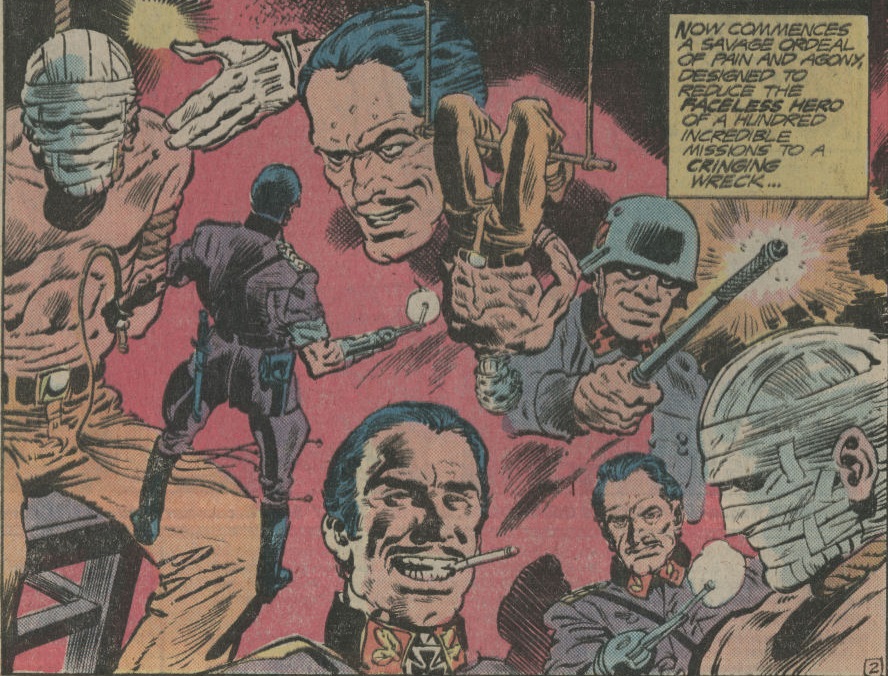

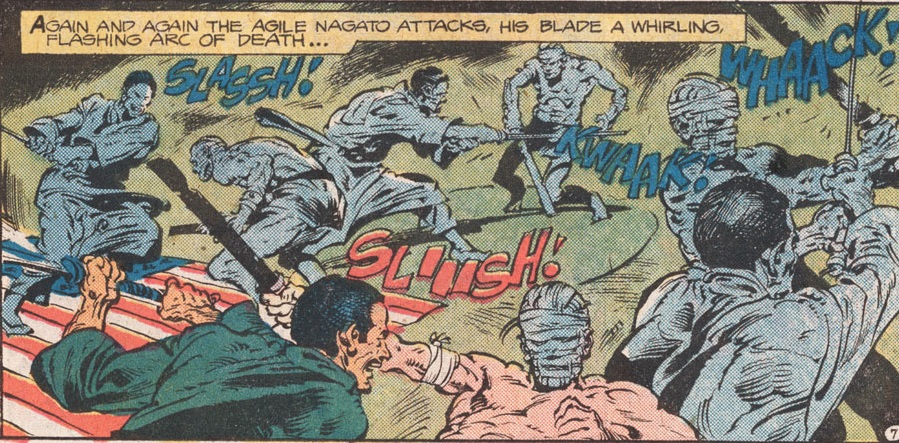

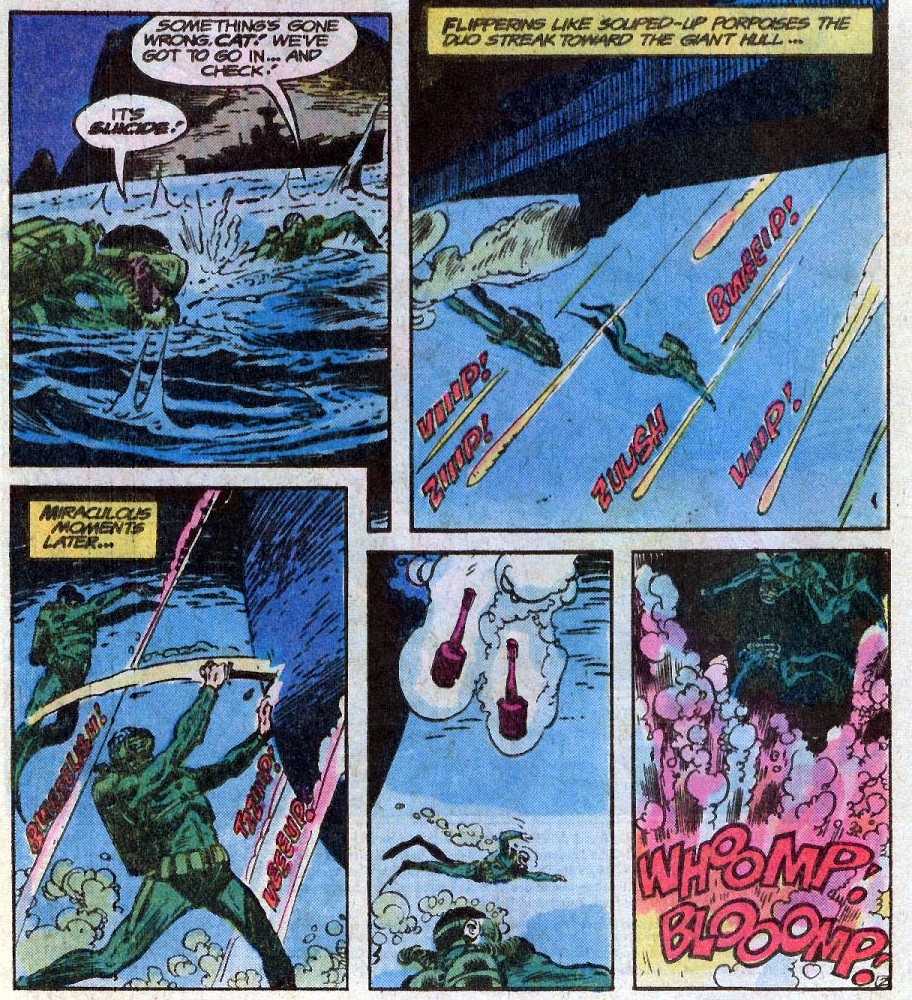

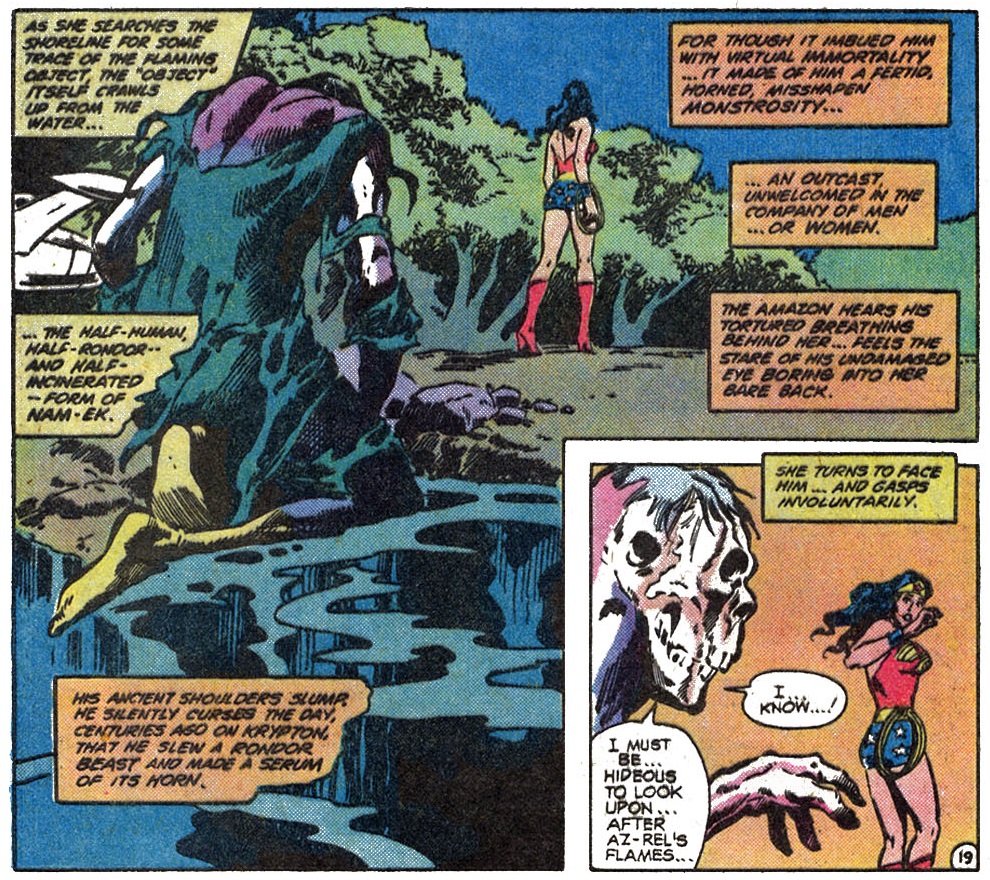

In the story, a group of prisoners, led by General Zod, manage to trade places with Superman, attacking the Earth while confining the Man of Steel (and a hapless, amnesiac former inmate) to the Phantom Zone. We thus get two simultaneous threads going on. On the one hand, we follow Superman’s quest to escape by travelling through increasingly surreal dimensional planes (like the Purple Realm, where he is attacked by horrendous-looking ‘leather-winged demi-demons,’ or the Temple of the Crimson Sun, with its freaky shape-shifting priestesses), culminating in a confrontation with the Phantom Zone’s demented god, Aethyr. On the other hand, we get to see a variety of eccentric Kryptonian outlaws from previous Superman comics – including a religious zealot and a man-hating female serial killer – wreck chaos around the world and face the remaining heroes, such as the Justice League of America, Wonder Woman, Supergirl, and Green Lantern (while the Caped Crusader investigates Clark Kent’s disappearance).

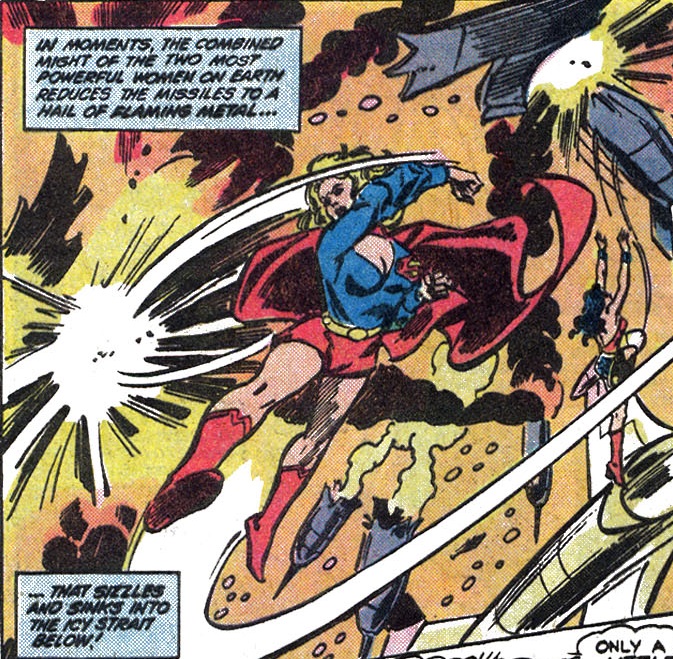

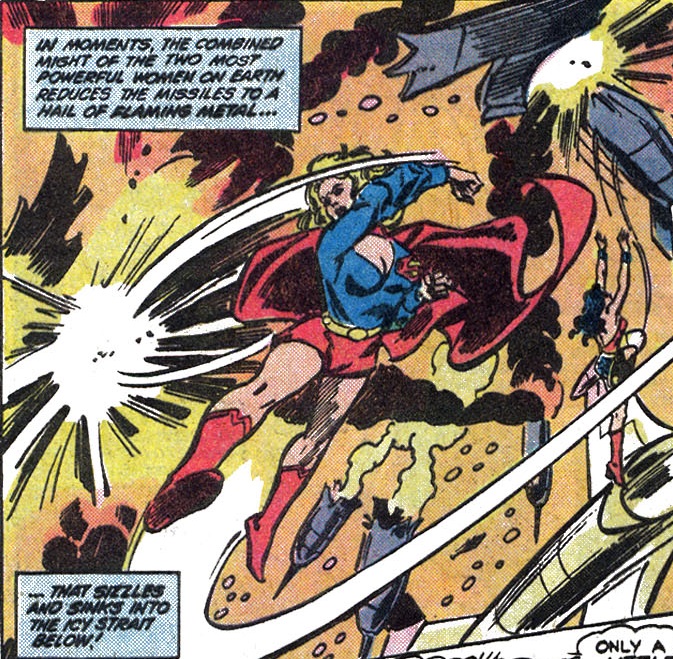

One of the first things to escalate the stakes, early on, is that a trio of evil Kryptonians destroys all of Earth’s communications and espionage satellites, with the predictable result that both the United States and the Soviet Union assume they are under attack by the other side and retaliate by launching their own missiles. This leads to an evocative sequence in which two women destroy the ultimate phallic symbol of war:

Phantom Zone #2

Phantom Zone #2

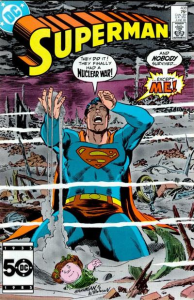

The comic thus fed into the nuclear obsession that was all over the Superman franchise throughout the eighties…

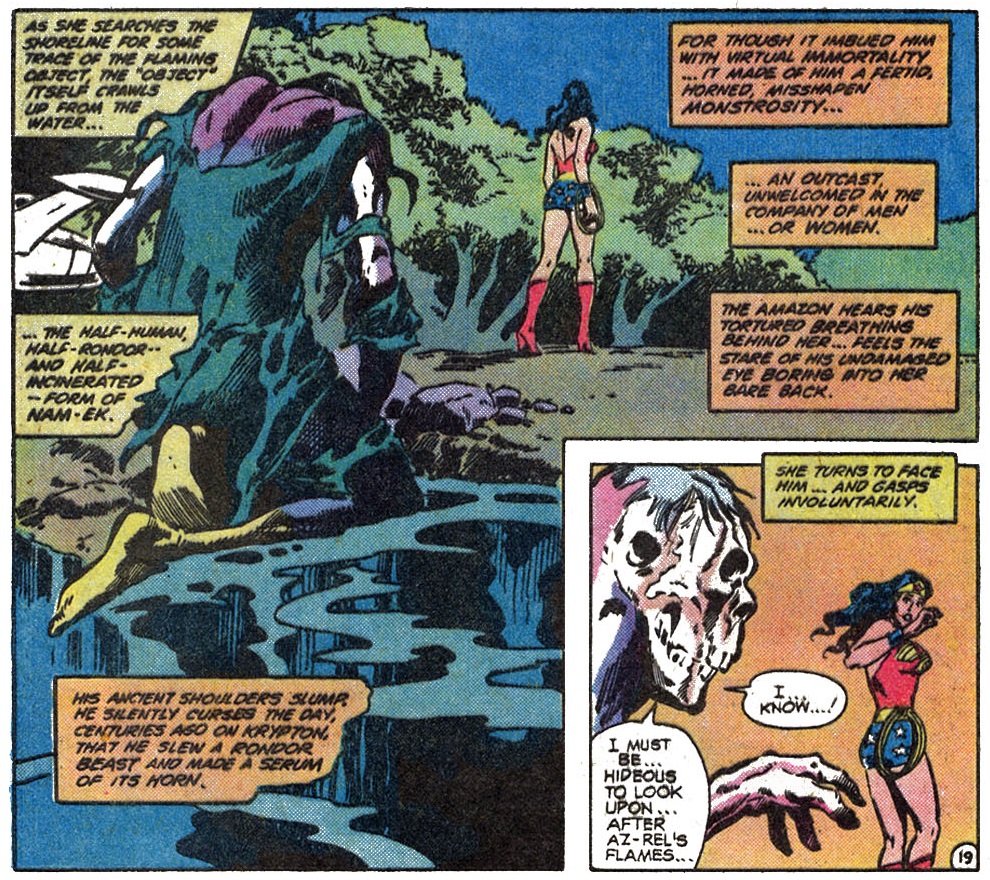

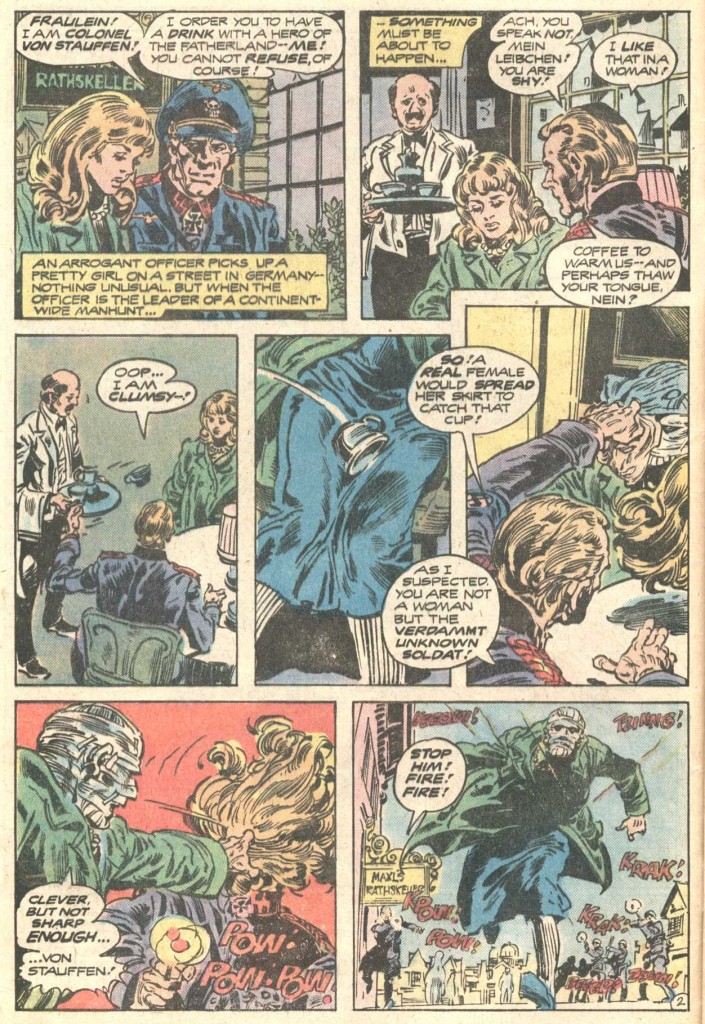

There was an unsettling tone to the whole affair. If Steve Gerber had a knack for coming up with eerie imagery, the same can be said of penciler Gene Colan (here inked by Tony DeZuniga), with his smoky figures and tilted panels… Indeed, many passages of Phantom Zone seem crafted through the language of horror, repurposing Superman’s colorful mythology for a different genre:

Phantom Zone #2

Phantom Zone #2

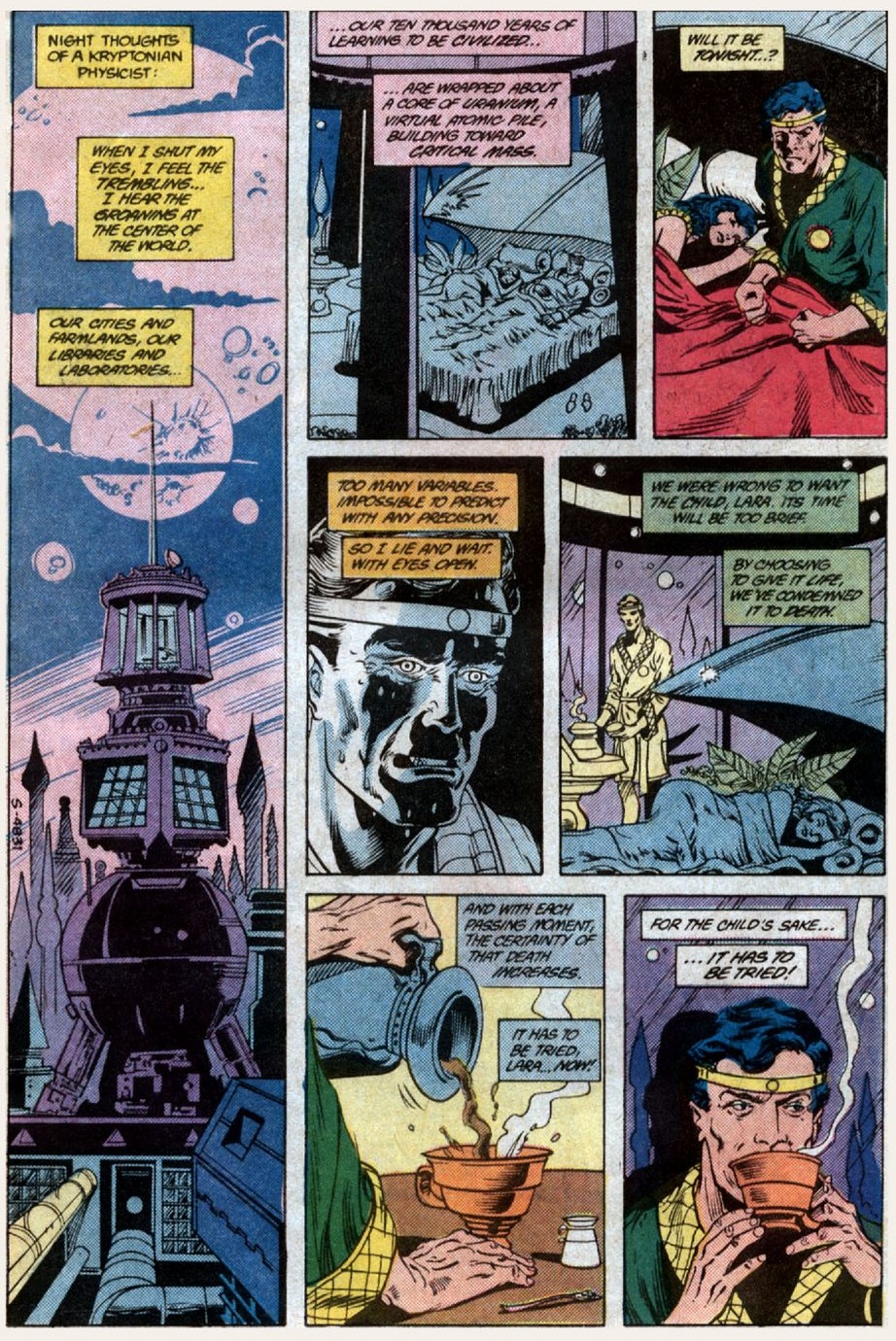

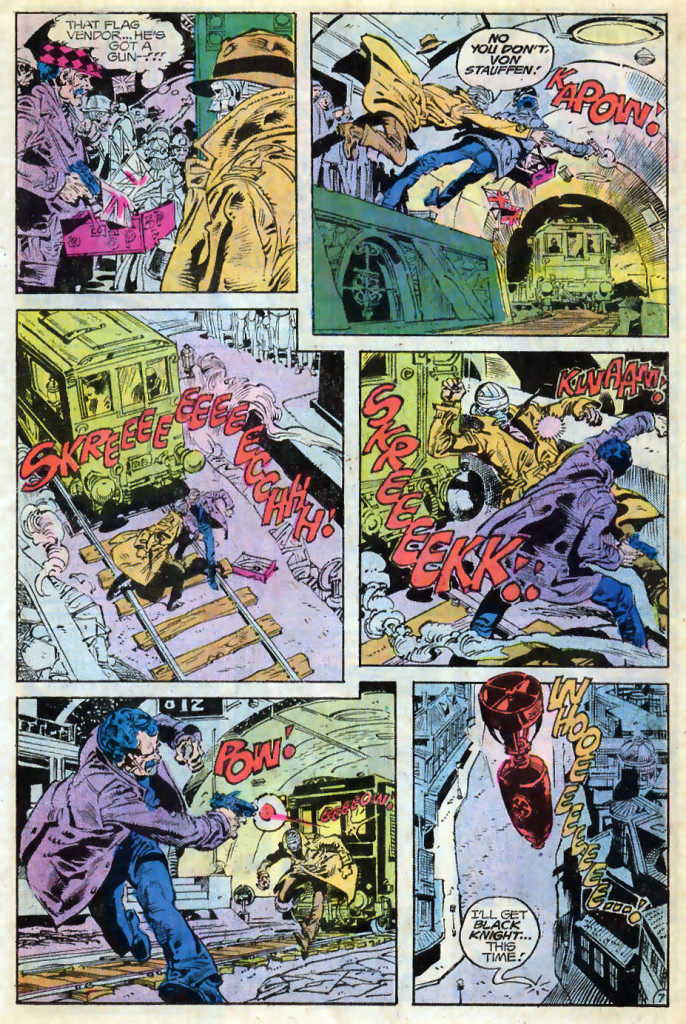

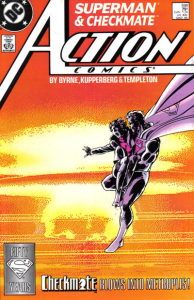

With this in mind, it was an inspired choice to assign the story’s trippy sequel to artist Rick Veitch, who has made a career out of combining horror and superhero visuals. Specifically, Steve Gerber revisited Phantom Zone’s cast in DC Comics Presents #97 (September 1986), the series’ final issue before the line-wide reboot ushered in by Crisis on Infinite Earths. Using the end-of-an-era moment to provide the culmination of decades of Superman continuity, this tale had Aethyr merge with Mr. Mxyzptlk and usher in a string of particularly sadistic attacks. However, unlike what Alan Moore did in the final pre-Crisis issues of Superman and Action Comics (with the acclaimed ‘Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?’), Gerber’s take on the ultimate Man of Steel adventure was pretty downbeat all the way, kicking off with a flashback that captured the doomed, apocalyptic mood of the Reagan era:

DC Comics Presents #97

DC Comics Presents #97

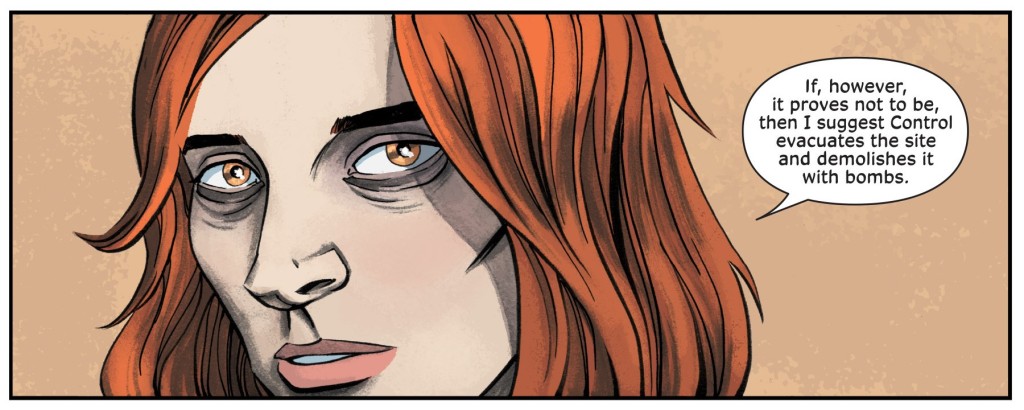

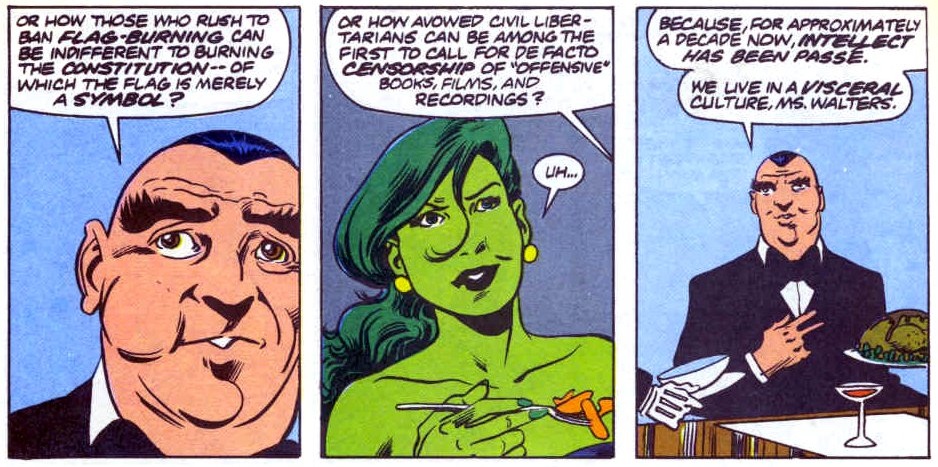

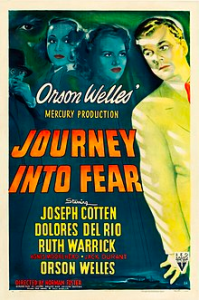

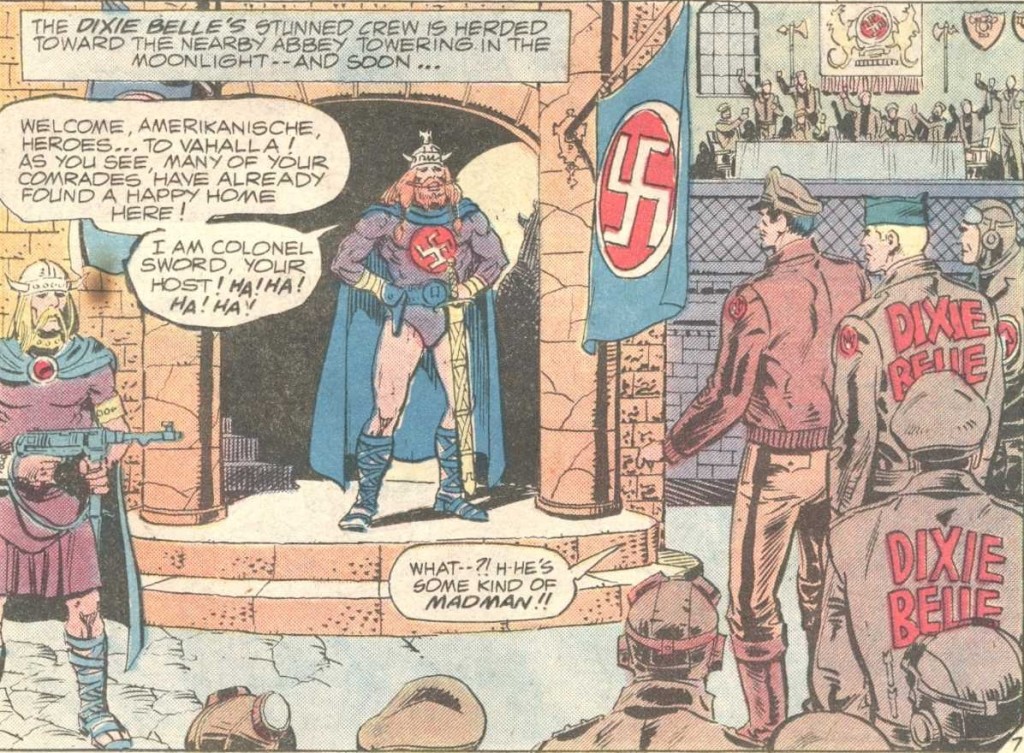

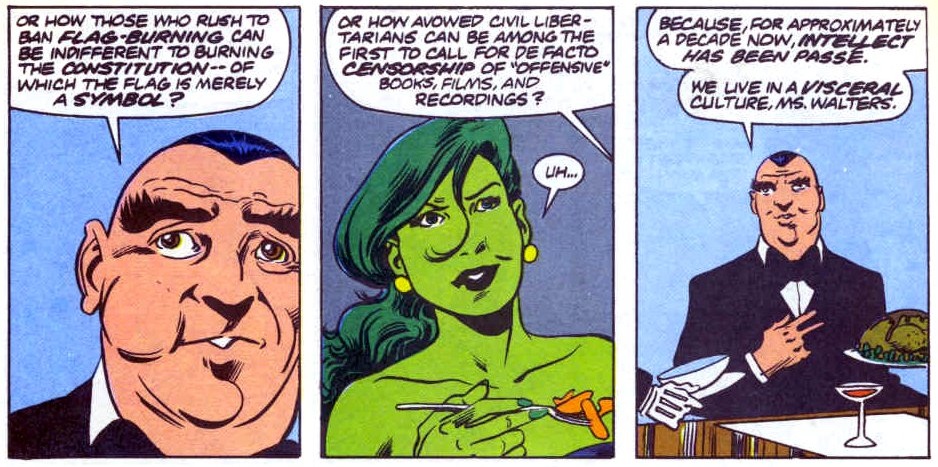

Together with Frank Miller, Steve Gerber also pitched a post-Crisis revamp of the Superman franchise (as well as of Batman and Wonder Woman), but DC ended up going with John Byrne’s clean-cut reboot instead. Perhaps as a form of cheeky payback, in 1989, when Gerber took over Byrne’s Sensational She-Hulk, back at Marvel, the first thing he did was to draw on Superman’s iconography to mock the superficiality of the surrounding media landscape. Playing with Lex Luthor’s new businessman look (while giving him more of a yuppie douchebag vibe through the addition of a ponytail), Gerber introduced billionaire Lexington Loopner, a misanthropic image consultant to celebrities and heads of state who used a system called ‘pseudonic analysis’ to assess social trends and then applied the data to promote his clients…

The Sensational She-Hulk #10

The Sensational She-Hulk #10

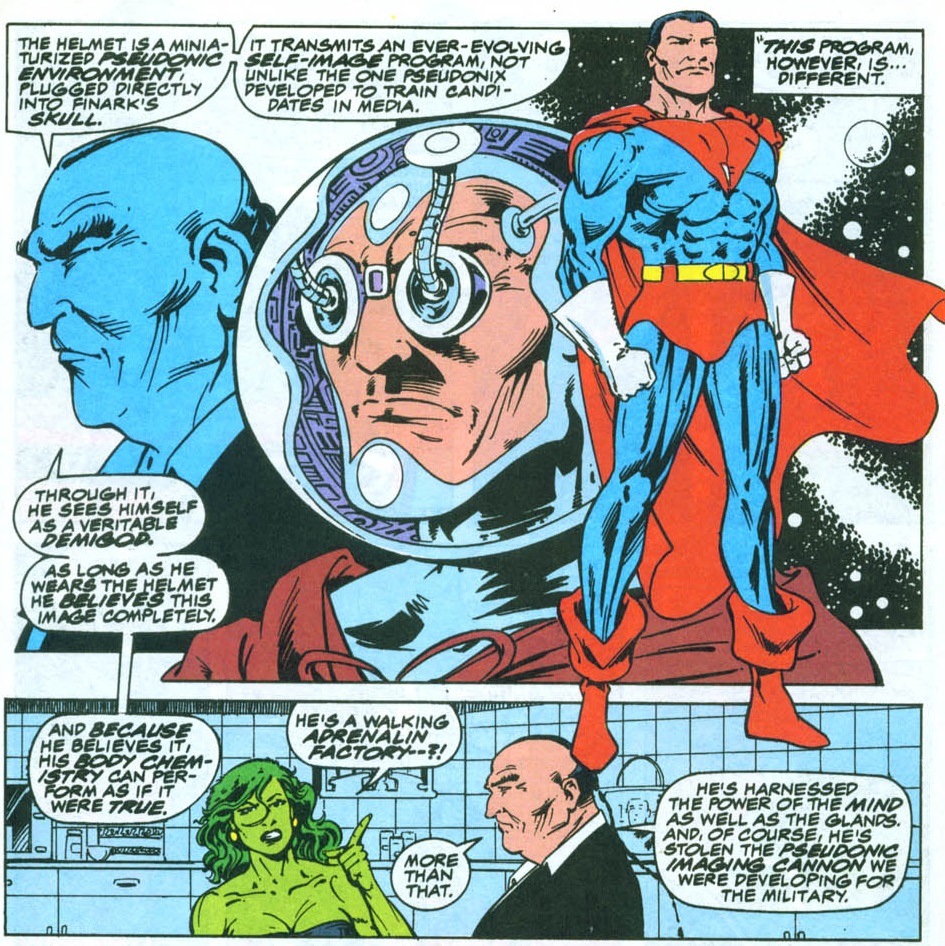

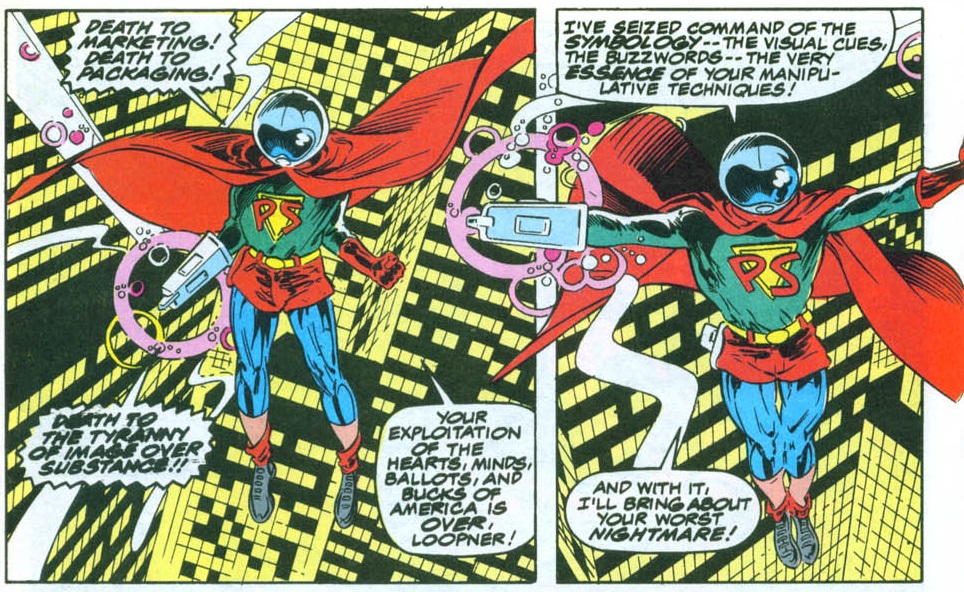

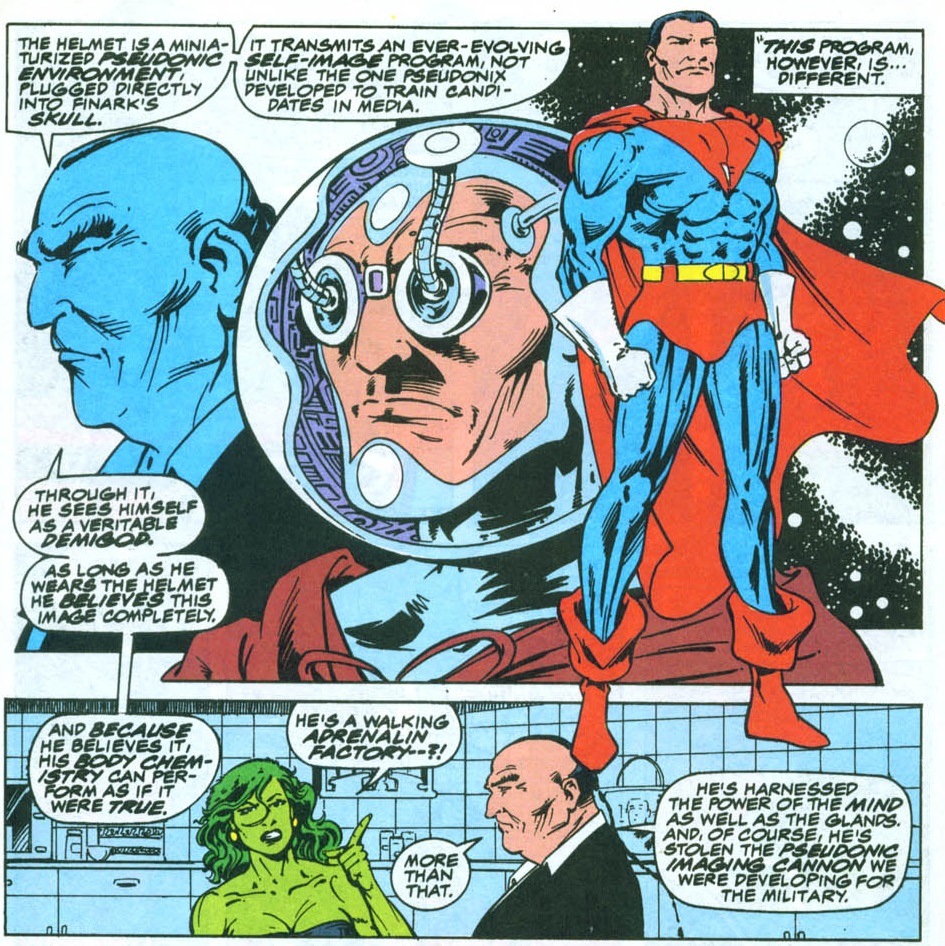

Bringing to mind debates that are still ongoing today, Lexington Loopner built a fortune on the principle that we live in a culture where ‘law and government are now a show.’ (‘When they bore or discomfit, attention drifts elsewhere.’) The essence of Loopner’s pseudonics was ‘communication without content,’ manipulating symbols to ‘generate pseudo-meanings for a society that gags on substance.’ However, when Loopner was hired to manage the campaign advertising of Clark Finark (subtle), a candidate for a Midwestern congressional seat, the campaign imploded once it came out Finark’s parents were either aliens from another planet or, at least, ‘60s acid casualties (‘in the current political climate, that may be worse than coming from outer space’). Finark then sought revenge by using pseudonic imaging technology, which essentially gave him super-powers:

The Sensational She-Hulk #11

The Sensational She-Hulk #11

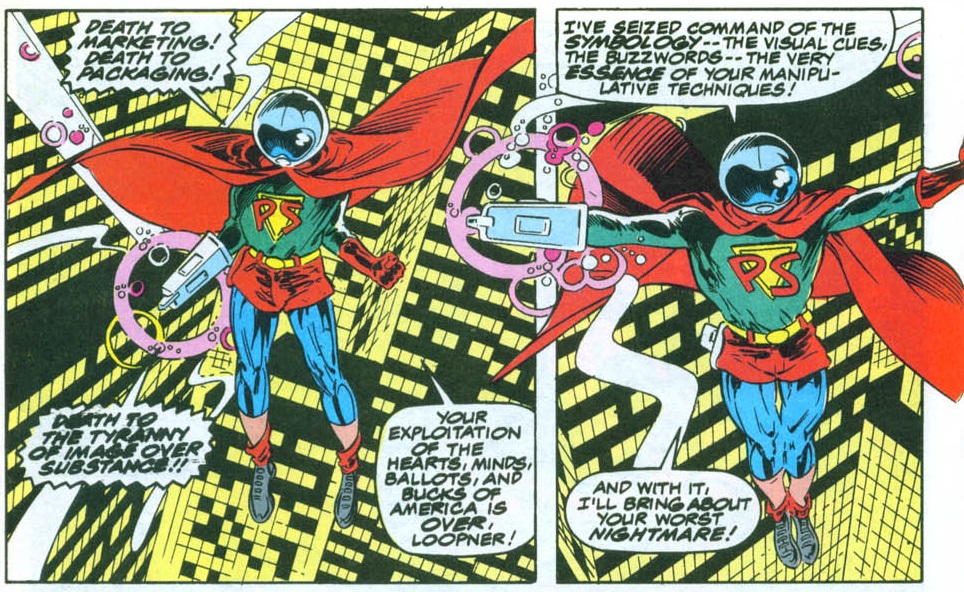

Ironically using the semblance of the Man of Steel (himself a symbol of lowbrow entertainment, consumerism, and even nationalism), Steve Gerber had Clark Finark assume the mantle of Pseudo-Man, a supervillain who sought to expose the icons of mass promotion by materializing their devastating power in New York City.

The ensuing iconoclastic mayhem served as the basis for an amazing gonzo sequence, lovingly rendered by a talented young Bryan Hitch:

The Sensational She-Hulk #11

The Sensational She-Hulk #11

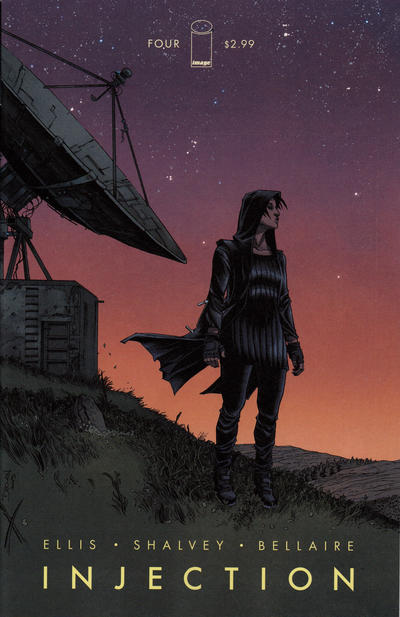

Steve Gerber wasn’t done with the Last Son of Krypton, though. Not only did he script episodes for 1988’s Superman and 1996’s Superman: The Animated Series television shows, but in 1999 he came back to DC Comics with a vengeance, penning the brilliant mini-series A. Bizarro.

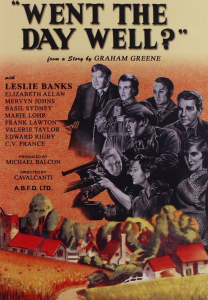

Bizarro, a flawed imitation of the Man of Steel who is essentially this hero’s funhouse mirror image (sick-looking, dumb-sounding, greeting people with ‘goodbye’) and whose thought-process and actions are backwards variations of Superman’s (including the fact that he lived in a cubic planet with messed up versions of Superman’s supporting cast, known as Bizarro World), is the kind of concept that seems perfectly suited to Gerber’s interests, as it is both nightmarish and an ideal springboard for social commentary (illustrating the inversions and paradoxes of our own world). However, other than a throwaway reference in Phantom Zone to a musical-cultural movement (‘beyond punk, beyond new wave, beyond modern lies’) known as Bizarro – whose basic tenet asserted that anyone born after 1961 (i.e. anyone under 20 at the time) was an imperfect duplicate of a human being – Gerber had only tackled this concept through a brief, amusing sequence in DC Comics Presents #97, which depicted Bizarro World’s destruction…

DC Comics Presents #97

DC Comics Presents #97

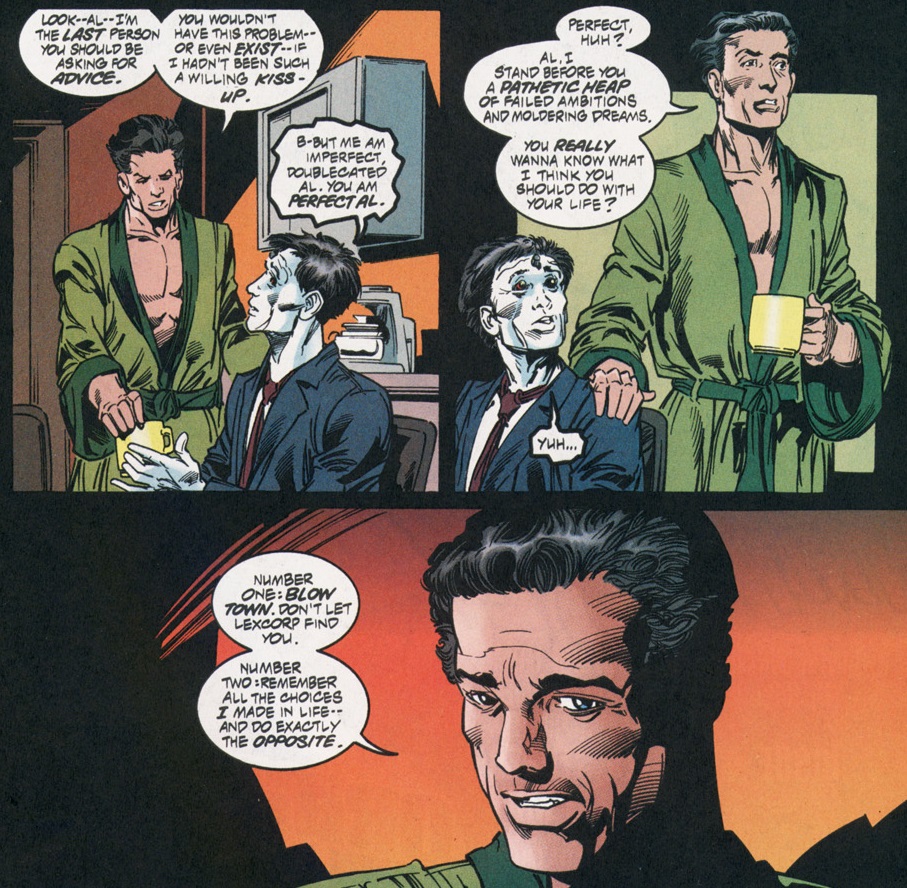

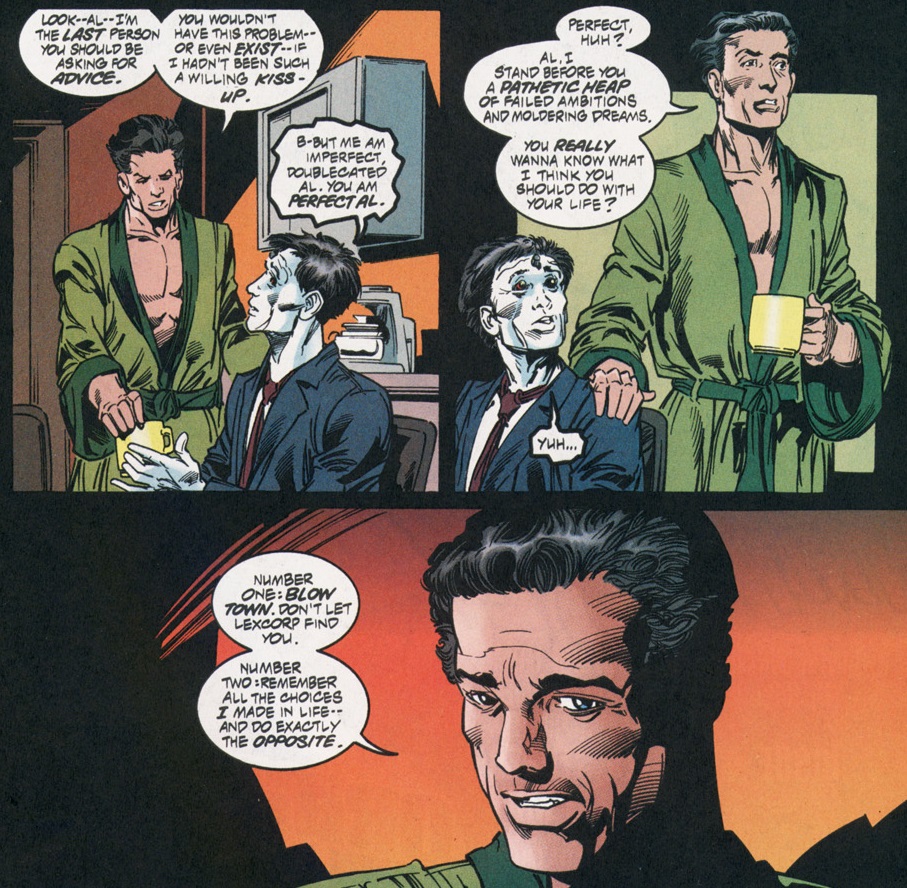

In A. Bizarro, we learn that the same Lexcorp project that failed to properly clone Superman (thus creating the post-Crisis iteration of Bizarro, from Man of Steel #5) was also used to clone Al Beezer, a worker from the company’s P.R. department. The ensuing shenanigans are funny yet oddly touching (both tones helped by the ultra-slick art and colors of Mark Bright, Greg Adams, and Tom Ziuko), as the original Beezer, who feels like an alienated loser after a couple of failed relationships, encourages his Bizarro counterpart to truly pursue an alternative life path:

A. Bizarro #1

A. Bizarro #1

Thus, instead of a reverse-Superman, we now get a reverse-1990s’ white-collar Joe Average – one who turns to begging, turns to crime, and (after a madcap trip to Apokolips) eventually becomes a rock star, only to end up leading a revolution in Central America!

The comic’s parodic slant is reinforced by the character of Lex Luthor, once again treated as an embodiment of corporate capitalism. As soon as he realizes this new Bizarro is a viable, if intellectually challenged, lifeform, Luthor immediately wants to know if they can have him procreate with a human female, presumably in order to breed a race of compliant workers. Later, when Al Bizarro becomes a successful musician, Luthor tries to claim all his profits on the basis that Lexcorp holds the patent on every cell in his body.

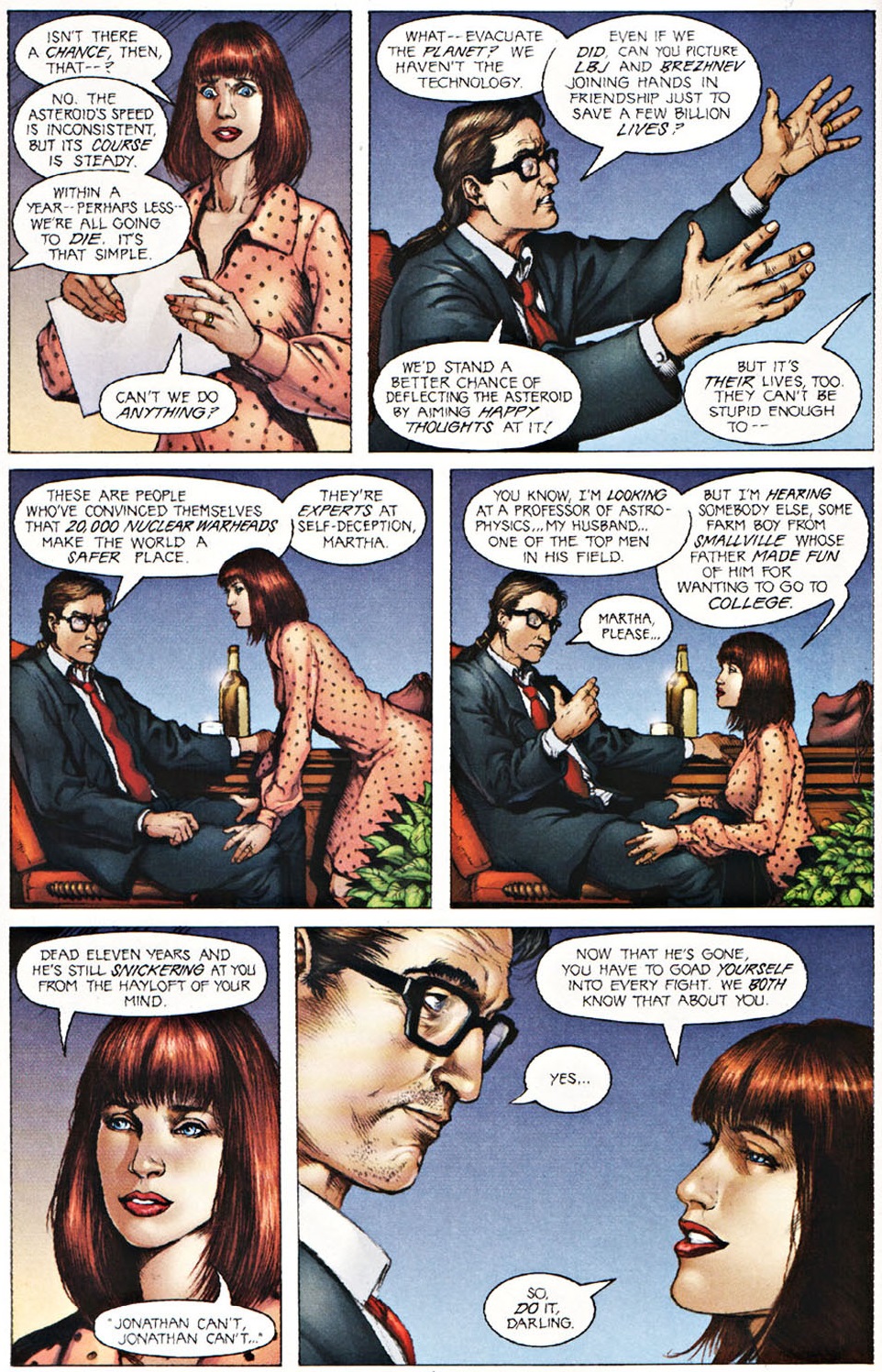

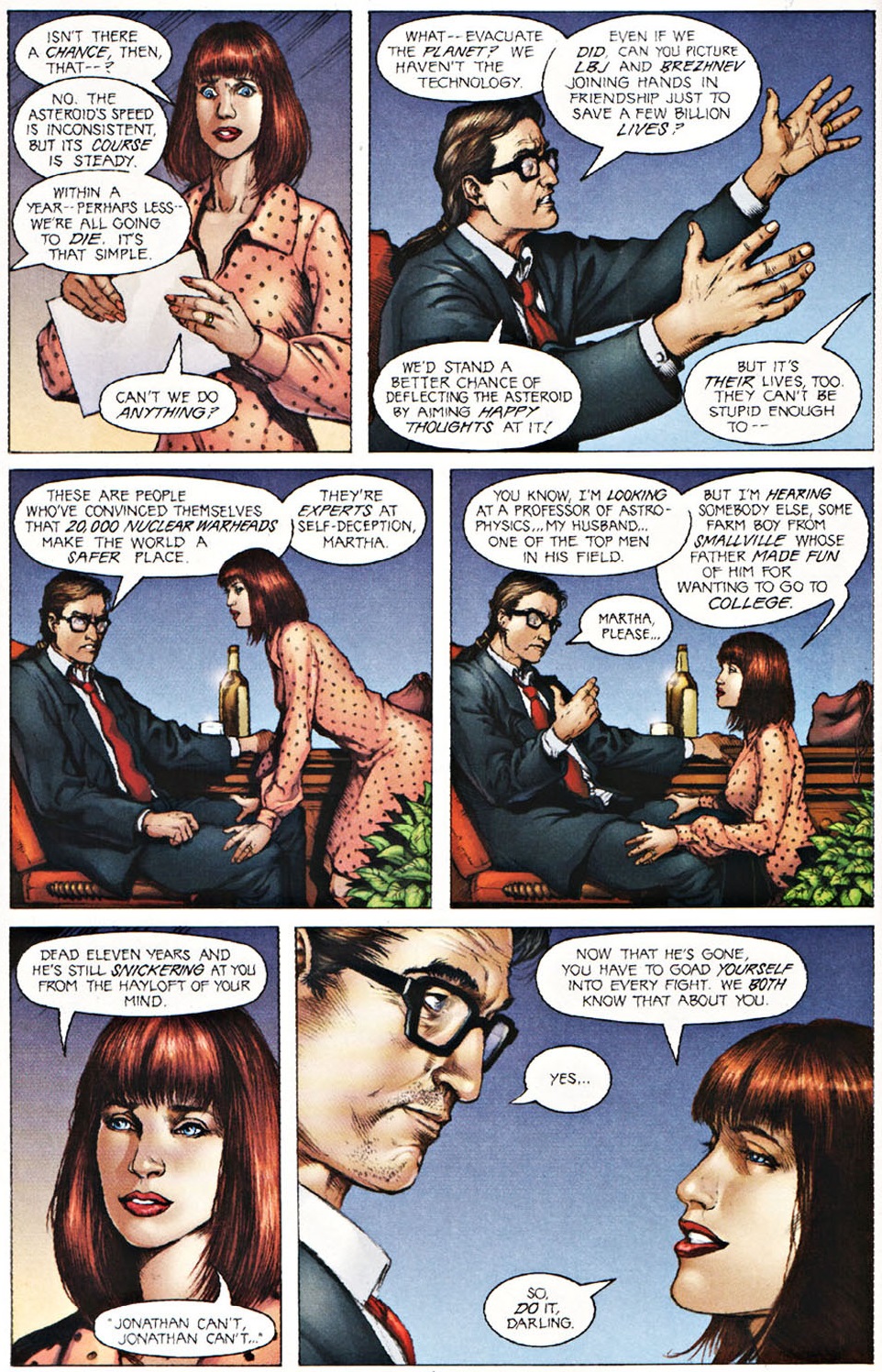

The following year saw the publication of an even cleverer mini-series, Last Son of Earth. In this Elseworlds tale, Steve Gerber fully turned the Man of Steel’s saga on its head by imagining a timeline in which it was the Kents who sent their baby into space (in the 1960s, after realizing an asteroid was about to destroy the Earth), so that that Clark actually crash-landed in Krypton. It was a cute high concept, but what elevated the comic was Gerber’s – and artist Doug Wheatley’s – committed execution. For one thing, they took what could’ve been mere functional plot points and imbued them with a surprising richness, fleshing out all the supporting players, starting with this reality’s Jonathan and Martha Kent…

Last Son of Earth #1

Last Son of Earth #1

(Like in the Man-Thing story above, the Cold War mindset comes across as a destructive, reactionary force…)

More than the individual characters, Steve Gerber had a blast delving into Kryptonian society and culture, building up on the planet’s post-Crisis history as had been told in John Byrne’s and Mike Mignola’s classic series The World of Krypton. Indeed, this is a proper sci-fi yarn: instead of settling for a symmetrical retelling of the original Superman story, Gerber freely lets the narrative unfold in unexpected directions, bringing in elements from the Green Lantern franchise and finally diving into post-apocalyptic fiction, as Wheatley channels Escape from New York while also riffing on the very first cover of Action Comics:

Last Son of Earth #2

Last Son of Earth #2

In 2003, Steve Gerber, Doug Wheatley, and colorist Chris Chuckry reunited for a sequel, the thrilling one-shot Last Stand on Krypton, which explored the political evolution of Earth and Krypton. On the surface, it may seem like Gerber was just once again pitting young idealists against councils of elders willing to make deals with the devil, but I can see in the comic a more ambiguous take on the issue of technological control… Both fanatical fear *and* blind praise of technology are cast as problematic, each trend embodied by the different villains (who ultimately turn against each other, illustrating the conflicting visions at play). That said, although validated by the narrative, Kal-El’s skepticism over how many resources to share with Earth, combined with his quest to unleash scientific progress in Krypton, cannot help but bring to mind the Global North’s patronizing attitude towards the South, especially when he frames things in terms of hierarchical, teleological development (‘Before the first mud brick of the first human city was laid, Krypton was reaching for the stars.’).

It was a final example of Steve Gerber twisting the material in a way that revealed the many contradictions it could contain. After all, there was surely something of Pseudo-Man in Gerber himself…

The Sensational She-Hulk #11

The Sensational She-Hulk #11