This is Gotham Calling’s 300th post!

I usually take these occasions to celebrate the richness and weirdness of Batman’s extensive rogues’ gallery, which includes all sorts of odd criminals, ranging from iconic characters like the Joker and the Penguin all the way down to this guy obsessed with eggs:

Batman: The Brave and the Bold #16

Batman: The Brave and the Bold #16

Flamboyant villains play a particular role in the Batman franchise. As Geoff Klock notes in How to Read Superhero Comics and Why, they tend to operate as a kind of reflection of some aspect of the Caped Crusader’s personality: ‘The Penguin reflects the dark side of Bruce Wayne’s millionaire capitalist playboy routine. Mr. Freeze points out the dark side of Bruce Wayne’s utter lack of emotion as Batman. The shape-shifter, Clayface, suggests the anti-essential nature of the Batman/Bruce Wayne relationship, both of which are seen as persona (Batman to scare criminals, Wayne to cover up Batman under the role of a disaffected rich fop). Poison Ivy uses criminal activity (and Batman’s vigilante status is, of course, illegal) for a good cause, ecology. The Scarecrow, whose entire existence is devoted to fear, recalls that the intention of the Batman persona is the edge provided by terror. The Mad Hatter’s mind control reflects the extremities of Batman’s methods of coercion. The Riddler parodies Batman’s role as the great detective.’

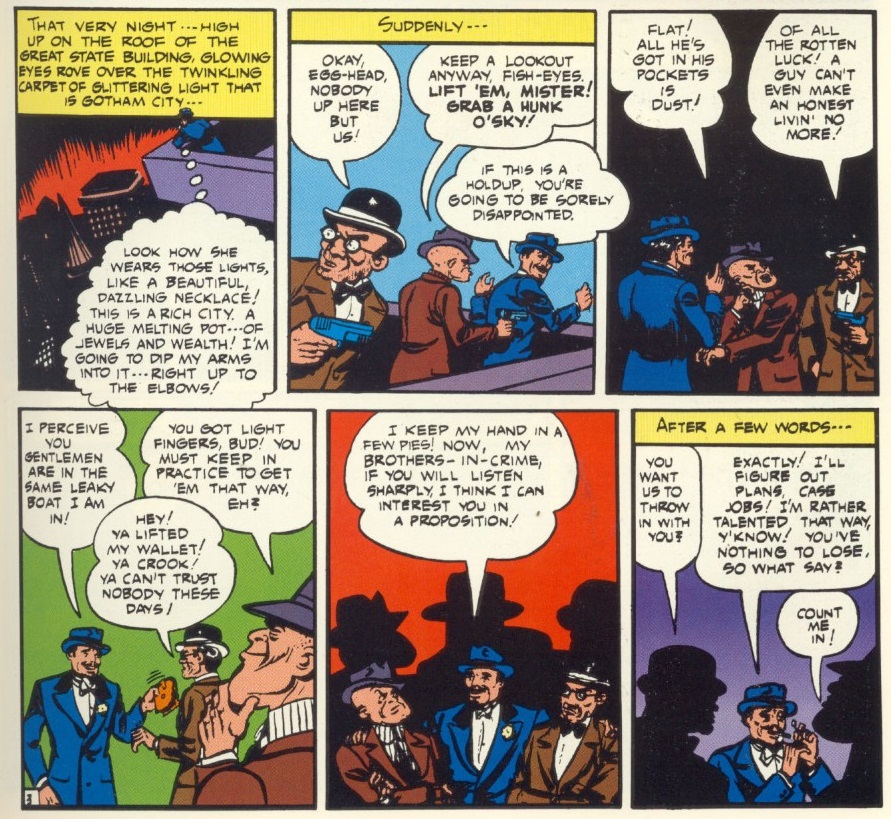

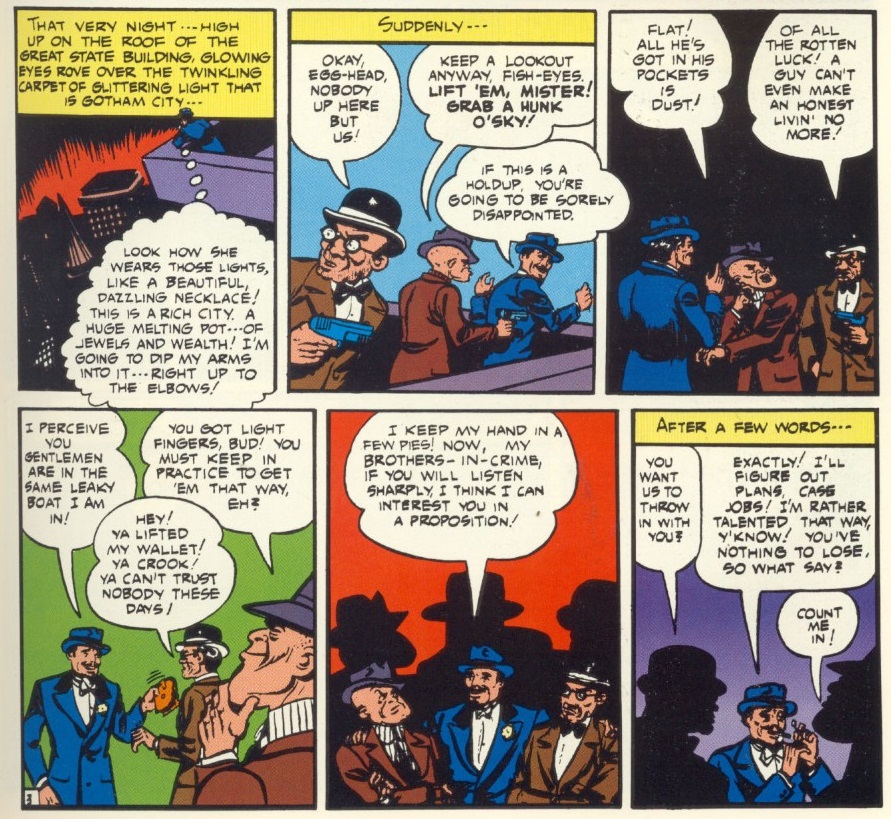

I’d say this goes even for many of the minor villains, including a few I find especially charming and underused. Let’s start with the most underused of the lot – Mr. Baffle, whose only appearance took place in ‘A Gentleman in Gotham!’ (Detective Comics #63, cover-dated May 1942), by Bill Finger, Bob Kane, Jerry Robinson, and George Roussos. This foe’s high concept was that he was an extravagantly suave jewel thief (or, as the introductory text put it, ‘clever as a fox’ and ‘romantic as some buccaneer of old’) who came to Gotham City after barely escaping from fascist Europe, where he had been sentenced to death by firing squad…

His escape is a delightful screwball sequence that tells you all you need to know about Baffle’s debonair coolness, snobbery, and cunningness:

Detective Comics #63

Detective Comics #63

Sure, there is something derivative about an ultra-refined criminal who feels at home in high society (it brings to mind the witty 1932 film comedies Jewel Robbery and Trouble in Paradise) and I’m certainly not saying Mr. Baffle should be amongst the Dark Knight’s greatest rogues (the ones that other creators shamelessly imitate). Still, Bill Finger does such a fine job of establishing Baffle’s gallant persona that it’s hard not feel a bit seduced by his cheerful charisma…

Detective Comics #63

Detective Comics #63

Even Batman succumbs to his charm: when Mr. Baffle first outmaneuvers him, the Caped Crusader’s reaction is, uncharacteristically, to laugh about it (in fact, they both laugh, sharing a sense of humor and fair play). There seems to be an implication that there’s a kind of class solidarity operating here, as Batman has more of a blast going up against this ‘chivalrous scoundrel’ than against the lowlifes he usually beats up. The growing mutual respect pays off at the climax, a sword duel in the aptly named Random Castle (‘transplanted from Scotland stone by stone’) where both hero and villain make a point of giving each other a sporting chance. In fact, this is a fun story all around, including a rollicking chase scene halfway through. Even Bruce Wayne’s socialite girlfriend at the time, Linda Page, has a role to play.

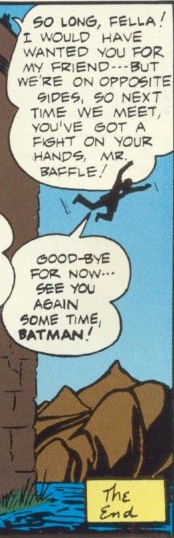

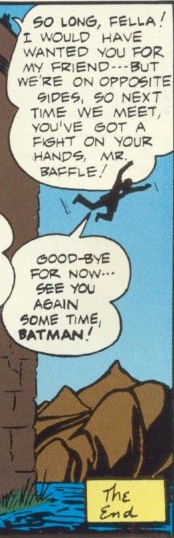

It’s a shame we never got to see Mr. Baffle again, especially as he played really well against Bruce’s own wealthy origins. The ending was clearly meant to set up Baffle as a recurring foe, but I guess we just have to accept that, for once, the villain didn’t make it after falling hundreds of feet into the water:

Detective Comics #63

Detective Comics #63

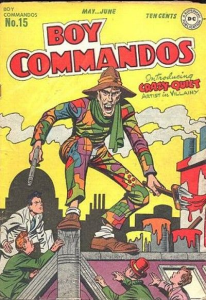

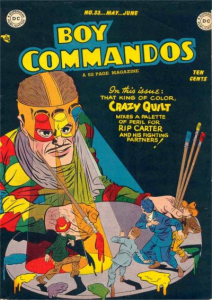

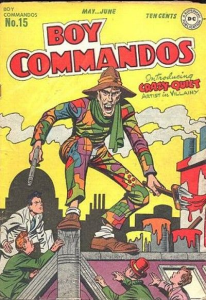

By contrast, one C-lister who came back a number of times is Crazy-Quilt, a Jack Kirby creation from way back in 1946 that has become a recurring butt of jokes about the lamest/goofiest side of Batman’s rogues’ gallery. A famed painter-turned-gang-chief, Quilt was shot by a rival gangster, which damaged his eyesight. After an unsuccessful medical operation, he became unable to see anything but bright colors – and, this being Gotham City, he devoted the rest of his life to committing color-based crimes!

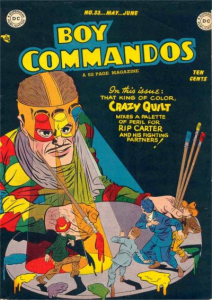

To be fair, Crazy-Quilt didn’t originally start out in Gotham, but in Paris, France, where he faced the Boy Commandos – the heroes of DC’s timeless series about an international team of children who somehow got together to fight Nazis during World War II.

Crazy-Quilt (aka ‘Madman of the Spectrum!’) showed up in a bunch of the Boy Commandos’ adventures in the mid-to-late forties, with cartoony plots – drawn ‘from his palette of plunder!’ – such as robbing the sarcophagus of an ancient pharaoh known for his love of vivid colors (including brilliant jewelry) and camouflaging a road in order in order to cause the crash of a truck full of payrolls (Wile E. Coyote would be proud). My favorite of the lot is a delirious tale in which Quilt colors the sky with a thousand giant rainbows in order to temporarily blind – and then raid – the city!

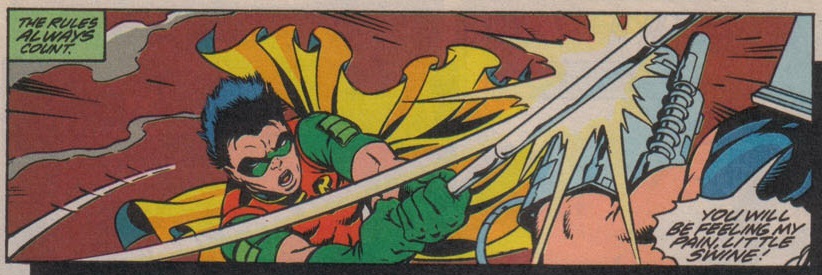

The transition to Batman’s corner of the DC Universe took place in Star Spangled Comics #123 (December 1951), where he fought Robin in what is still Crazy-Quilt’s best story. He would only come across the Dark Knight himself almost thirty years later, though, in Batman #316 (October 1979), and even then Quilt remained more of a Robin villain than a Batman one – which makes sense, since the Boy Wonder is obviously the most colorful of the two (in both senses of the word).

That first comic hits the ground running, as Crazy-Quilt (‘this Renegade of the Rainbow’) breaks out of prison by discreetly smearing bits of paint on the blades of a ventilating fan throughout the winter, so that by summer, when the fan is activated, its spin creates a hypnotic combination of colors that allows him to escape. Quilt then tries to steal all the color in Gotham City, something he seeks to achieve by spraying bleach on colored pennants, cutting the circuits of color television sets, and destroying a bunch of Paul Gauguin paintings.

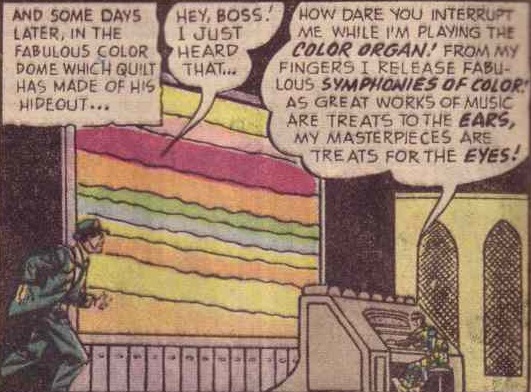

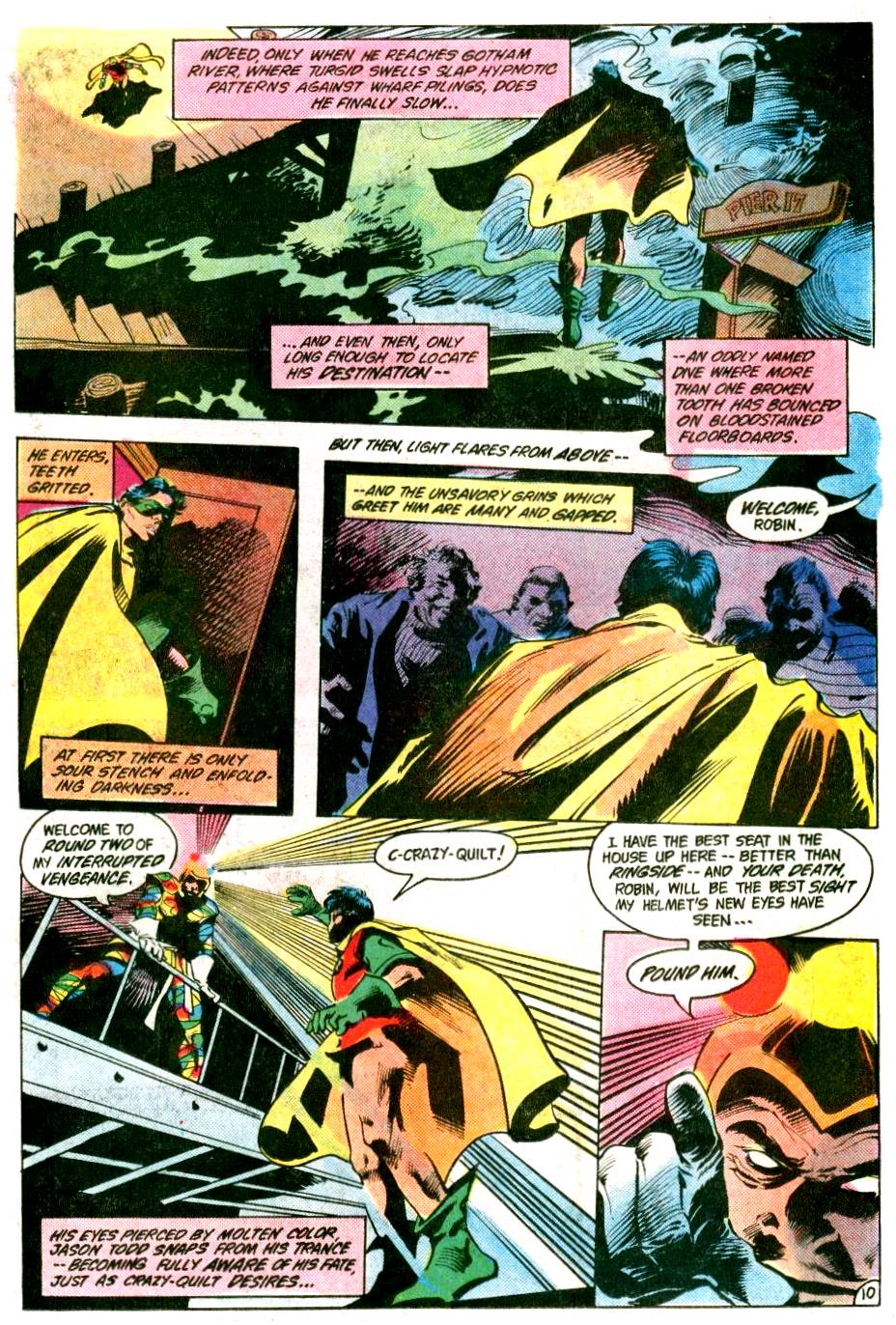

Above all, the creative team of France Herron and Jim Mooney have a field day with the fact that Crazy-Quilt is still an artist at heart:

Star Spangled Comics #123

Star Spangled Comics #123

This is the most underused aspect of Crazy-Quilt: he isn’t just a campy criminal with a ridiculous look, he’s a character perfectly suited for tales featuring art-based clues and art-based capers (it should come as no surprise that one of the few stories to take advantage of this in a really neat way was an episode of the animated show Batman: The Brave and the Bold, namely ‘The Color of Revenge’).

Crazy-Quilt is also an ideal vehicle for dazzling visual experimentation, as both his costume (including a bizarre headpiece that projects red, yellow, and blue lights in order for him to see) and his crime sprees lend themselves to psychedelic depictions, which can work quite well in the hands of inventive artists and colorists.

Boy Commandos #33

Boy Commandos #33

Indeed, contrary to popular opinion, I don’t actually regard Crazy-Quilt as necessarily lame – he’s just a zany embodiment of an era of surreal, imaginative villains who looks particularly out-of-place in a modern age with a more predominantly gritty, pseudo-realistic sensibility. (This was also Kevin Smith’s approach to the character in The Widening Gyre #4.)

The problem with pitching Crazy-Quilt as a pathetic loser, of course, is that it makes Batman and Robin come across like cruel bullies… especially when the Dynamic Duo full-on blinds him for good:

Batman #316

Batman #316

(This isn’t a pretty moment… In fact, it should belong to the pantheon of things DC wants you to forget about Batman.)

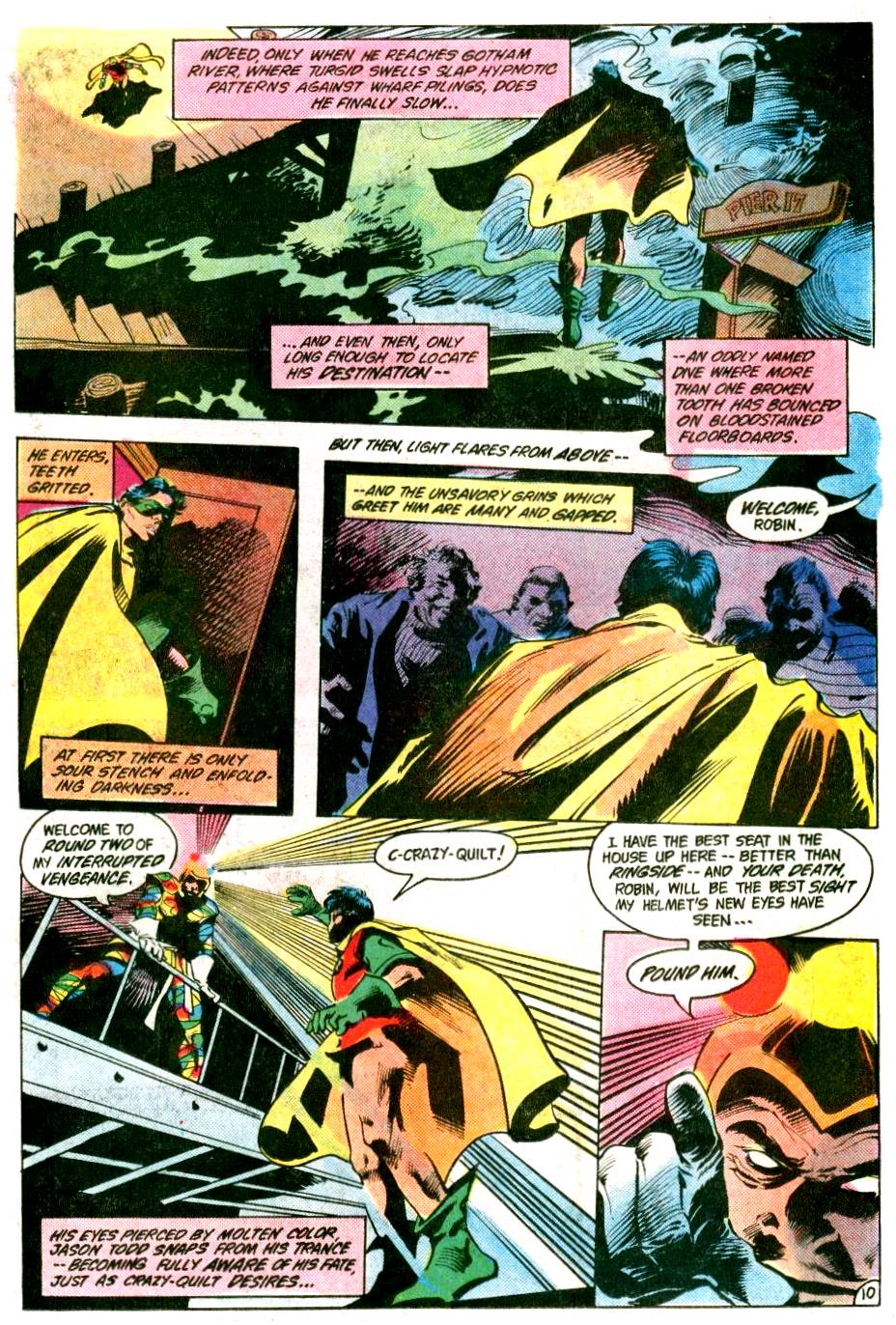

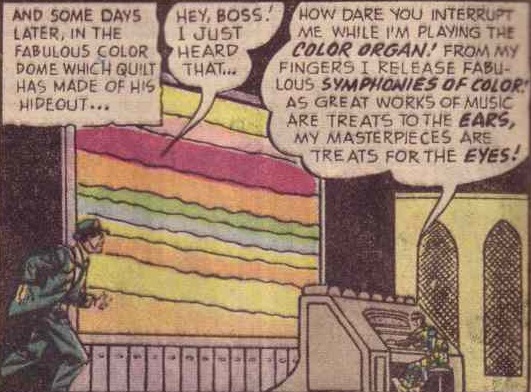

Well, Crazy-Quilt didn’t exactly stay blind forever… He was eventually able to force a mercenary doctor to hook him up with three colored lenses that fed image signals through implant cables directly into the brain’s sight-centers, bypassing his eyes. Quilt then sought vengeance against Robin, unaware that Dick Grayson had by then passed the sidekick mantle on to an unexperienced Jason Todd.

This happened in the two-parter ‘A Revenge of Rainbows/One Hole in a Quilt of Madness’ (Batman #368 and Detective Comics #535, both cover-dated February 1984), which, like much of Doug Moench’s excellent eighties’ run, took the silliest concepts from Batman’s back catalogue and played them with a straight face. Fortunately, colorist Adrienne Roy was more than up to the challenge of selling bright colors as something sinister, eerily blending vivid hues with menacing shadows, especially when working over Gene Colan’s fluid pencils:

Detective Comics #535

Detective Comics #535

(Naturally, a major part of the palette consists of Moench’s own deep purple prose.)

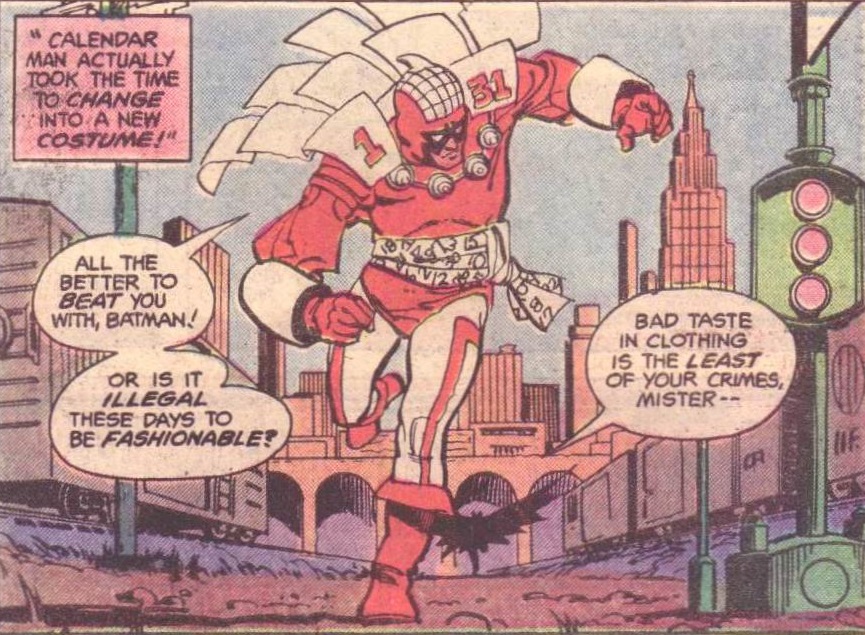

Thinking back to the Geoff Klock interpretation I mentioned earlier in the post, the fact that crooks like Crazy-Quilt embrace crime in Gotham City as a sort of performance art ends up neatly reflecting Batman’s own performative approach to crime-fighting. With that in mind, I have always admired Calendar Man’s emphasis on aesthetics as expressed through his various fashion statements.

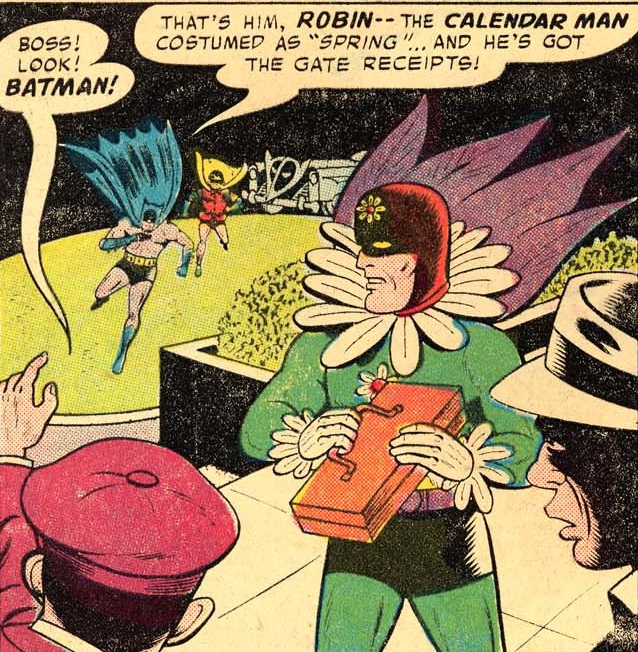

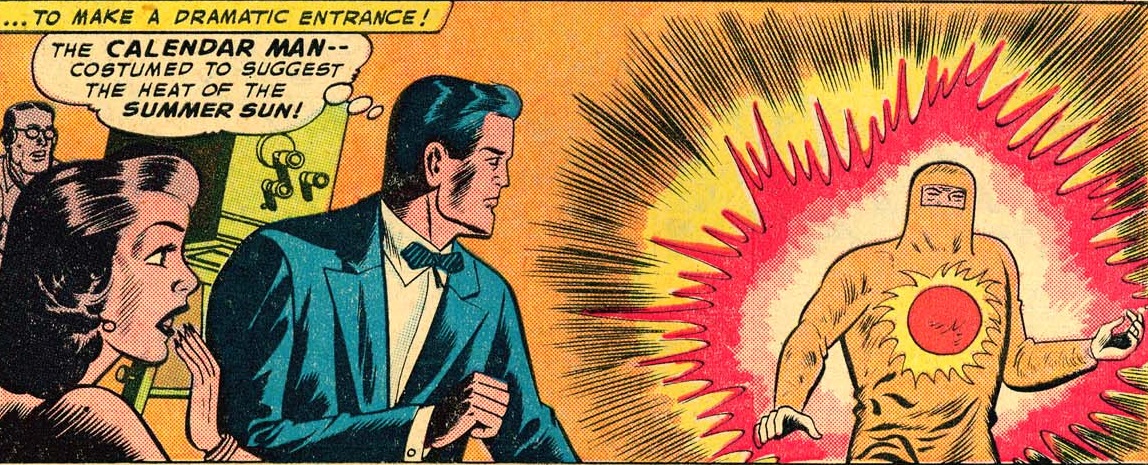

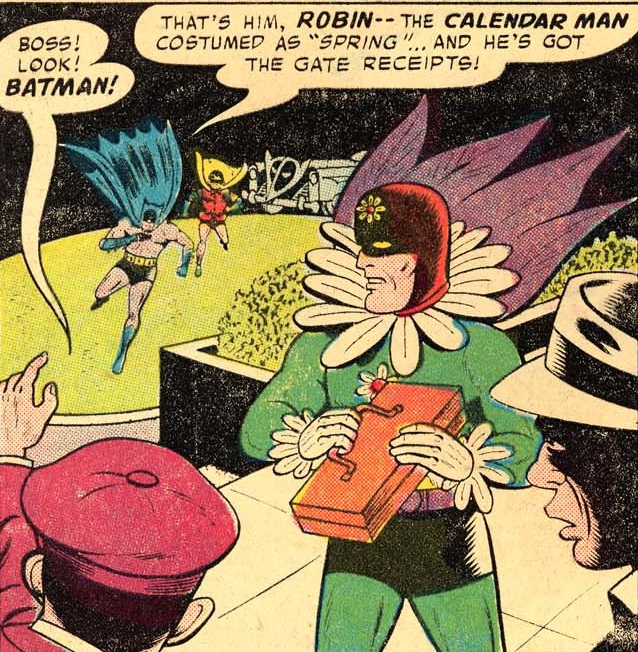

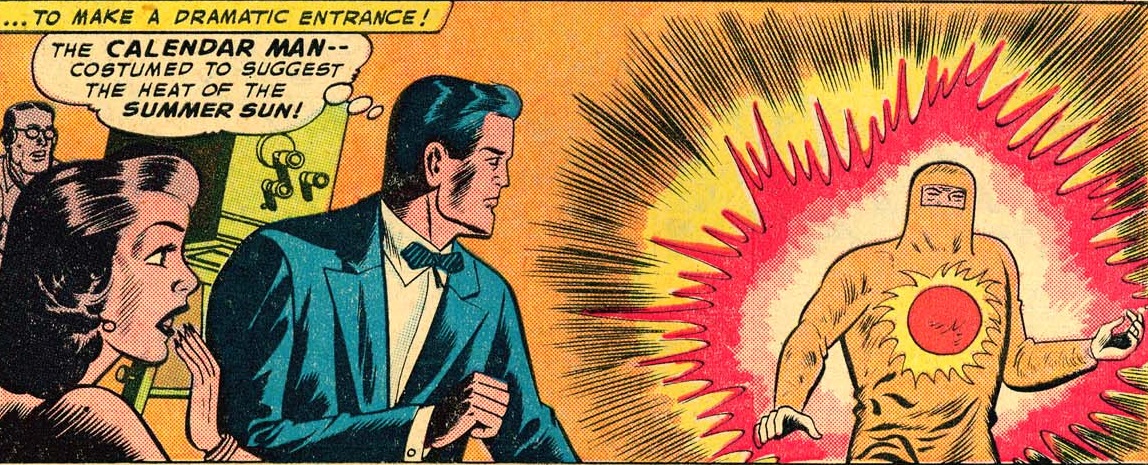

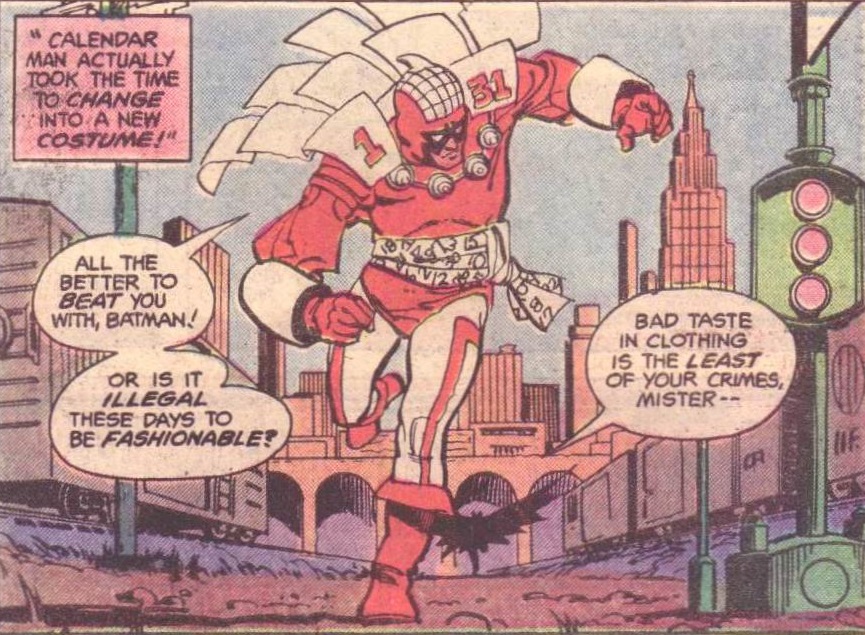

Batman’s rogues tend to have outrageous costumes, with slight variations throughout their careers. When he first started, however, Calendar Man actually got a completely new costume for each crime, the campier the better. A proud product of the Silver Age (he made his debut in in Detective Comics #259, September 1958), Calendar Man’s gimmick was that each of his robberies was related to the date in which it was committed – and so were his outfits, which reflected, for example, the time of the year (as designed by Sheldon Moldoff)…

Detective Comics #259

Detective Comics #259

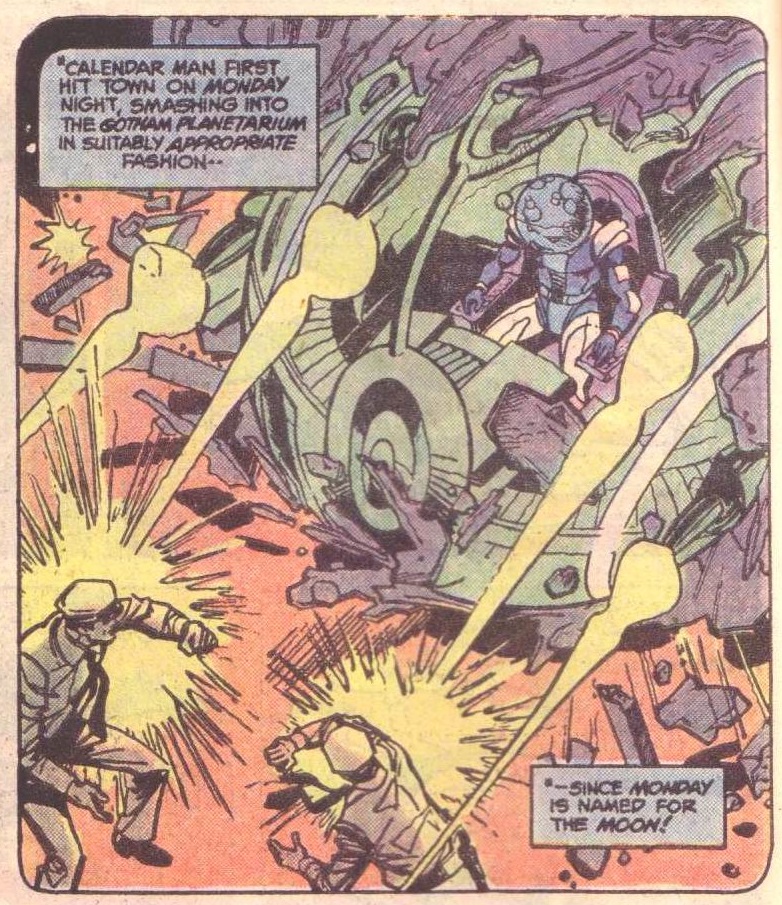

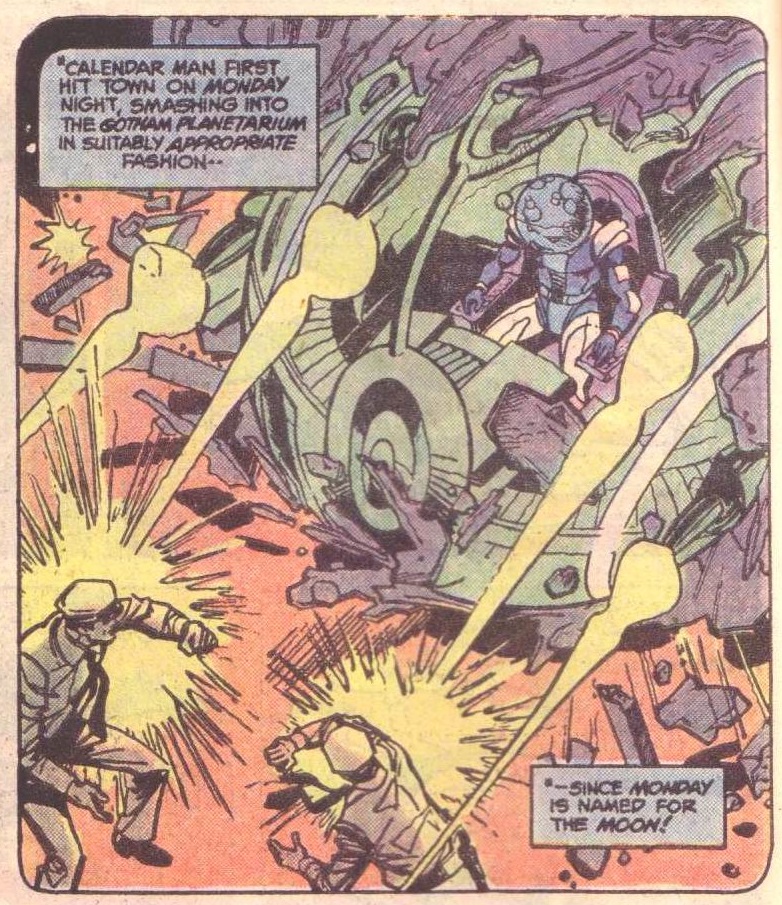

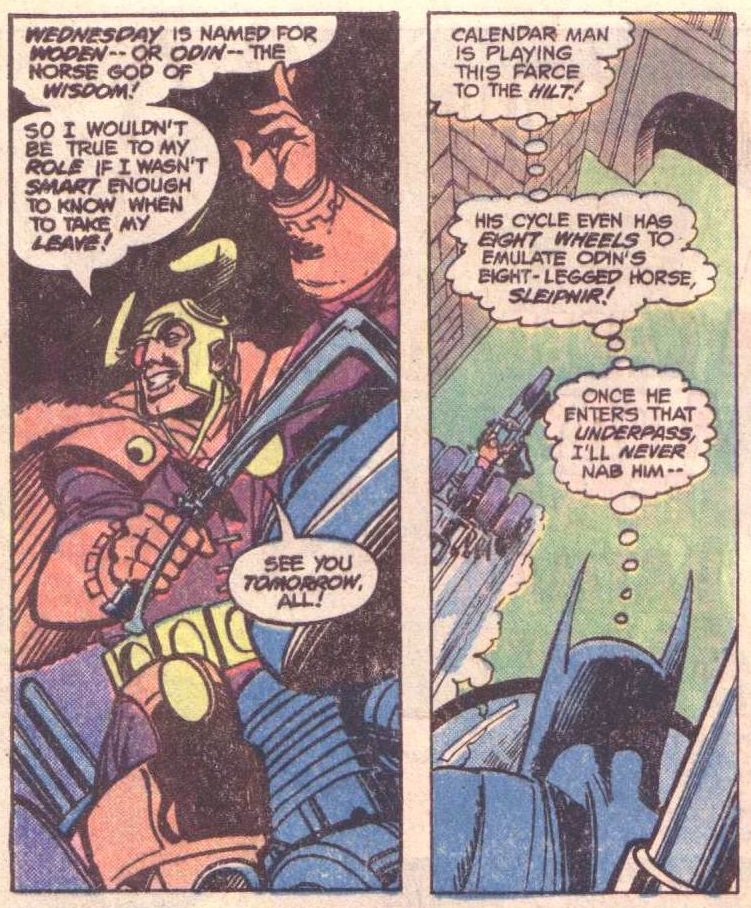

…or the day of the week (by Walt Simonson)…

Batman #312

Batman #312

…or just significant dates of the American calendar, like Valentine’s Day and the Fourth of July (by Pat Broderick and Rick Hoberg ):

Detective Comics #551

Detective Comics #551

Batman #385

Batman #385

(That underwear is quite something, isn’t it?)

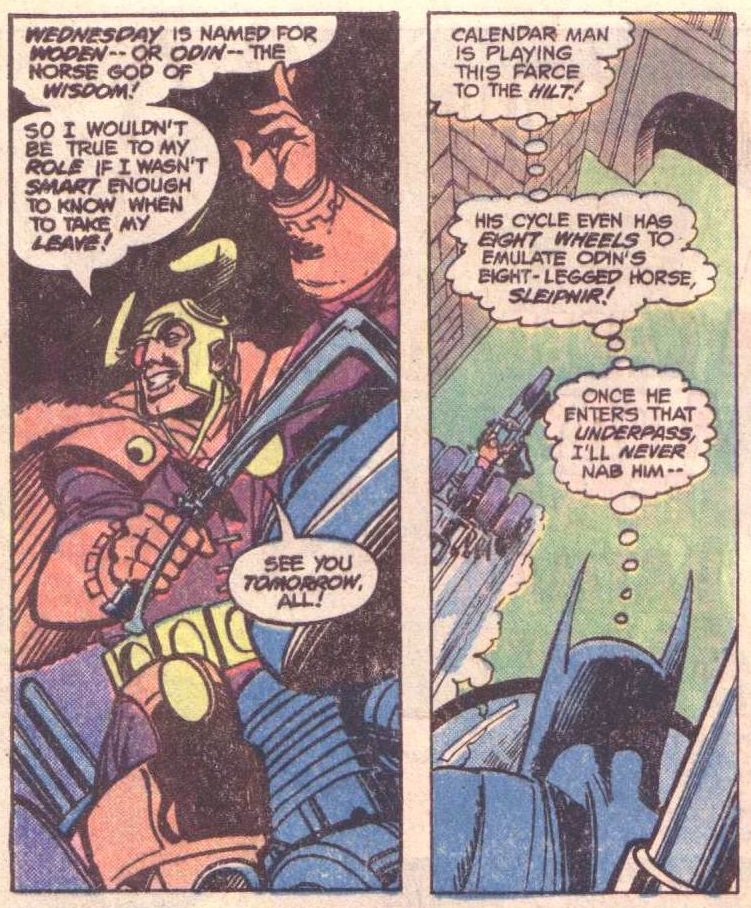

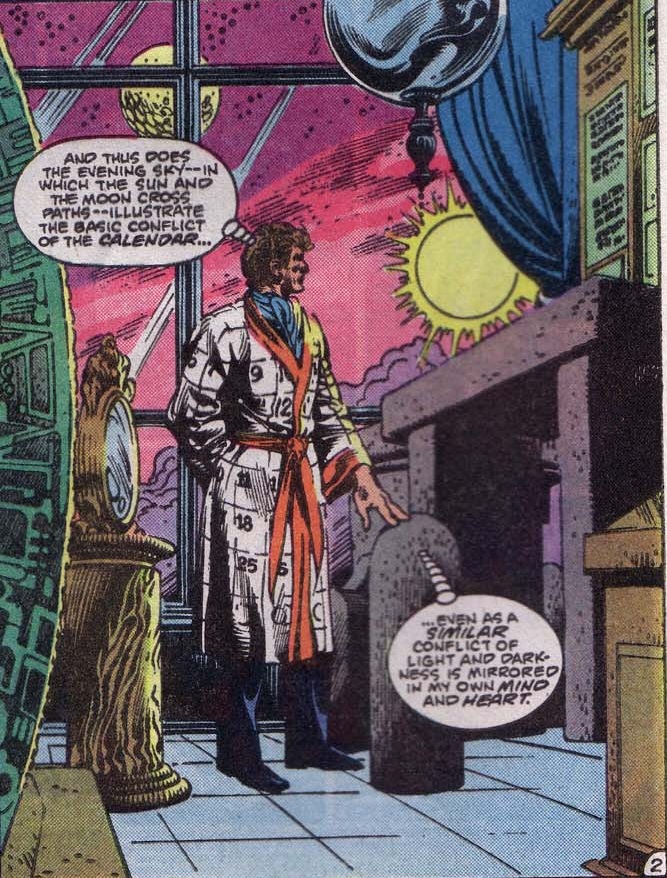

You can just imagine him at home, in his calendar robe (Hoberg again), pondering what to wear for his next artistic crime (or criminal work of art?):

Batman #384

Batman #384

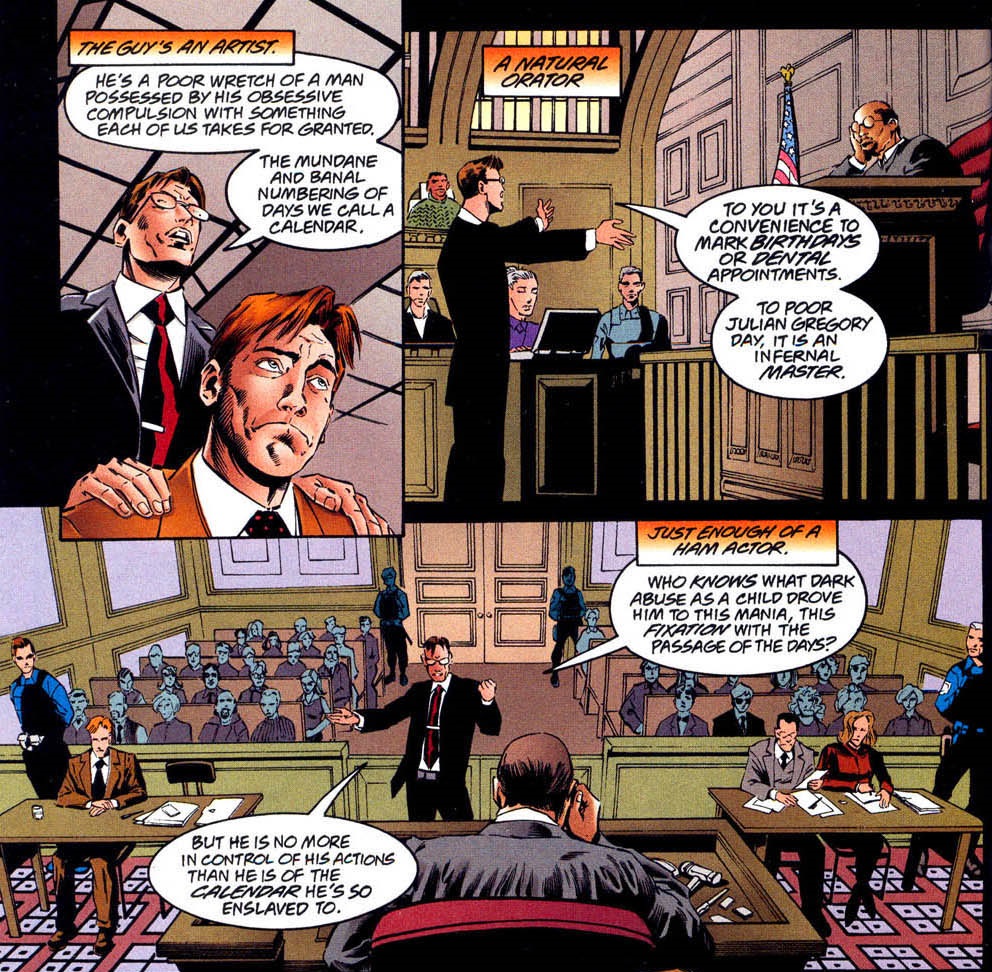

Seriously, here is a guy who truly puts a lot of effort and creativity into his heists’ sartorial dimension. In fact, since Calendar Man lacks a fully fleshed origin – apart from the fact that his name is Julian Gregory Day and in Gotham City your name predetermines your psychosis – his main motivation appears to be the very desire to dress up.

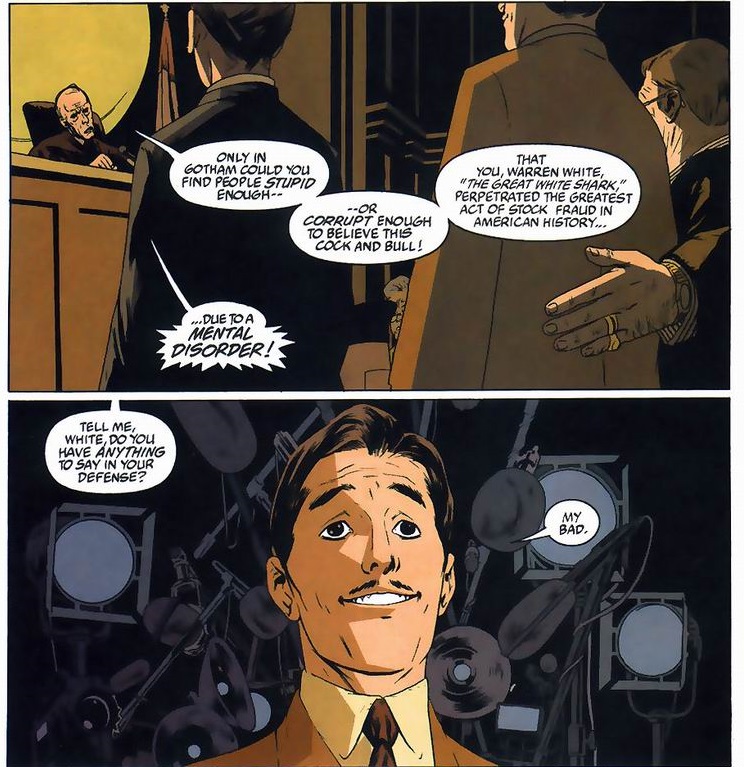

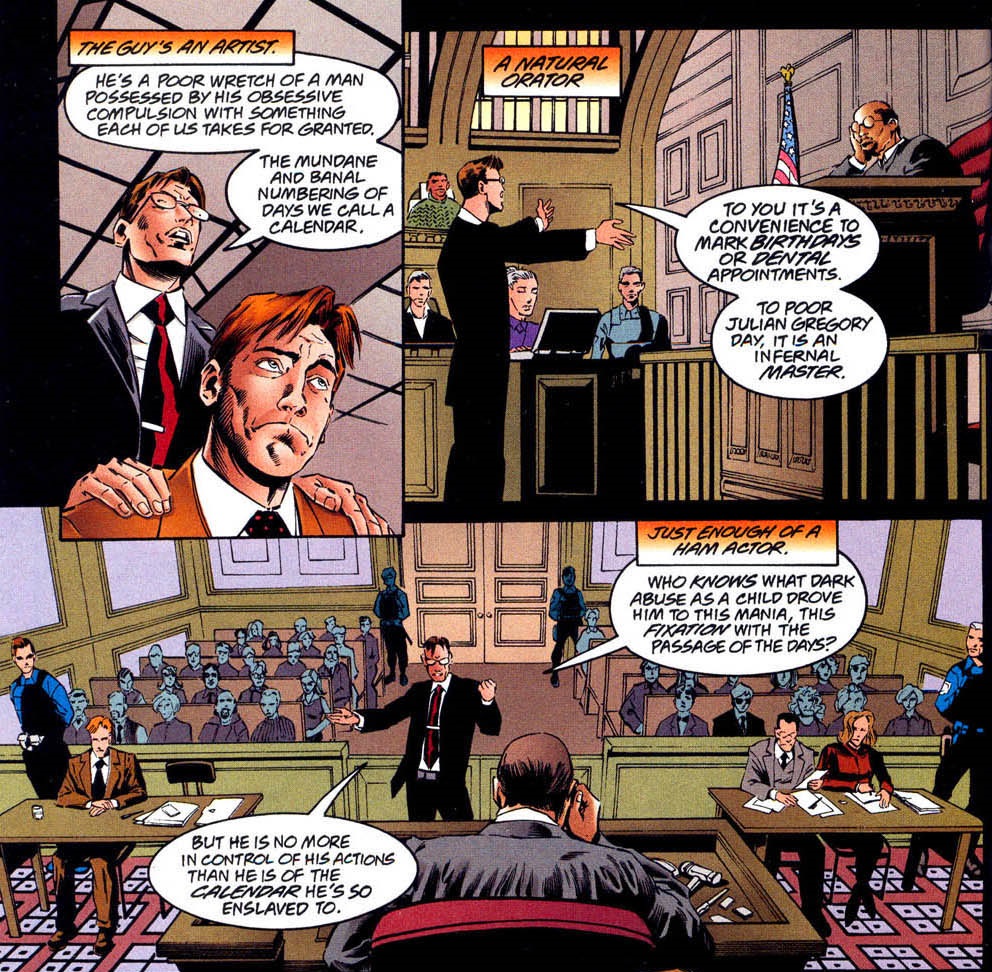

Hey, as explanations go, it’s both less depressing than the mini-origin we got in ‘Every Day Counts’ (Batman 80-Page Giant (v2) #1, February 2011) and a lot more convincing than the bullshit his lawyer came up with:

Batman 80-Page Giant #3

Batman 80-Page Giant #3

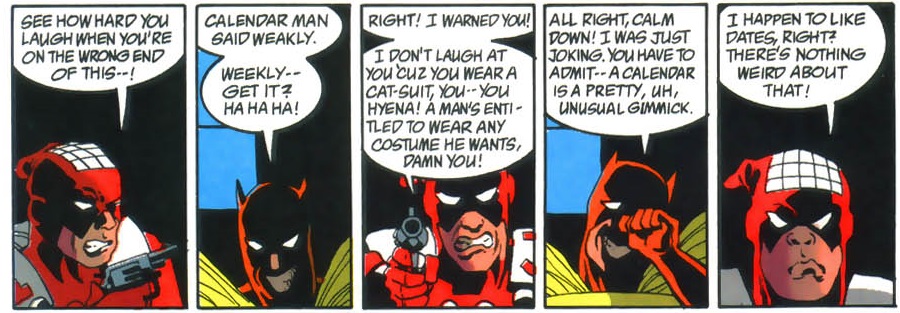

Indeed, once you take into account the fact that Julian Day used to be a stage magician, I don’t think it’s too farfetched to suggest that at the core of Calendar Man’s heart is a sense of spectacle and pageantry, with robberies being more of a pretext to perform than anything else.

Batman #312

Batman #312

In the broader history of Batman comics, Calendar Man’s overall arc is actually similar to Crazy-Quilt’s. Having been abandoned for decades as ill-suited to the Dark Knight’s hip credentials, they were both recovered by the great Len Wein in the late ‘70s and subsequently picked up for a multi-parter in Doug Moench’s abovementioned mid-80s run, which treated them with relative dignity.

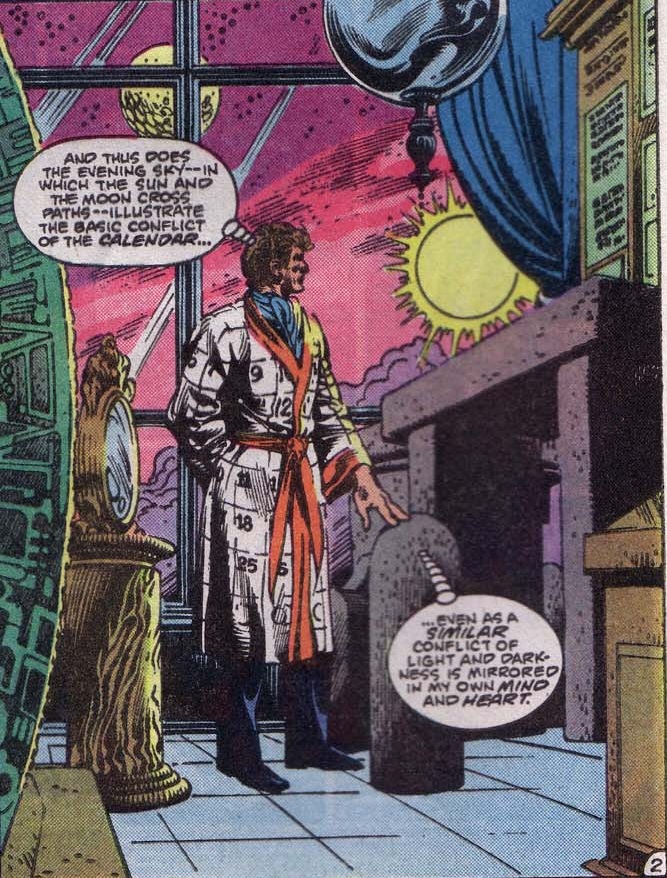

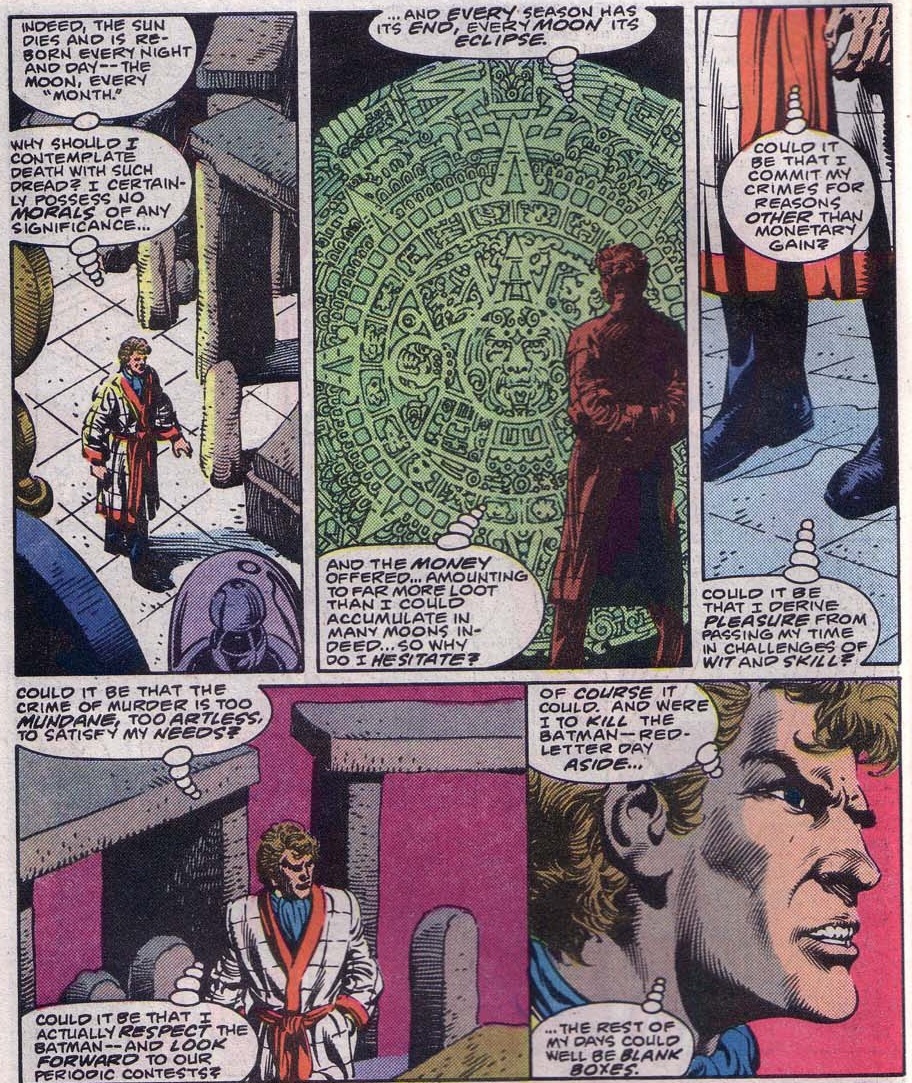

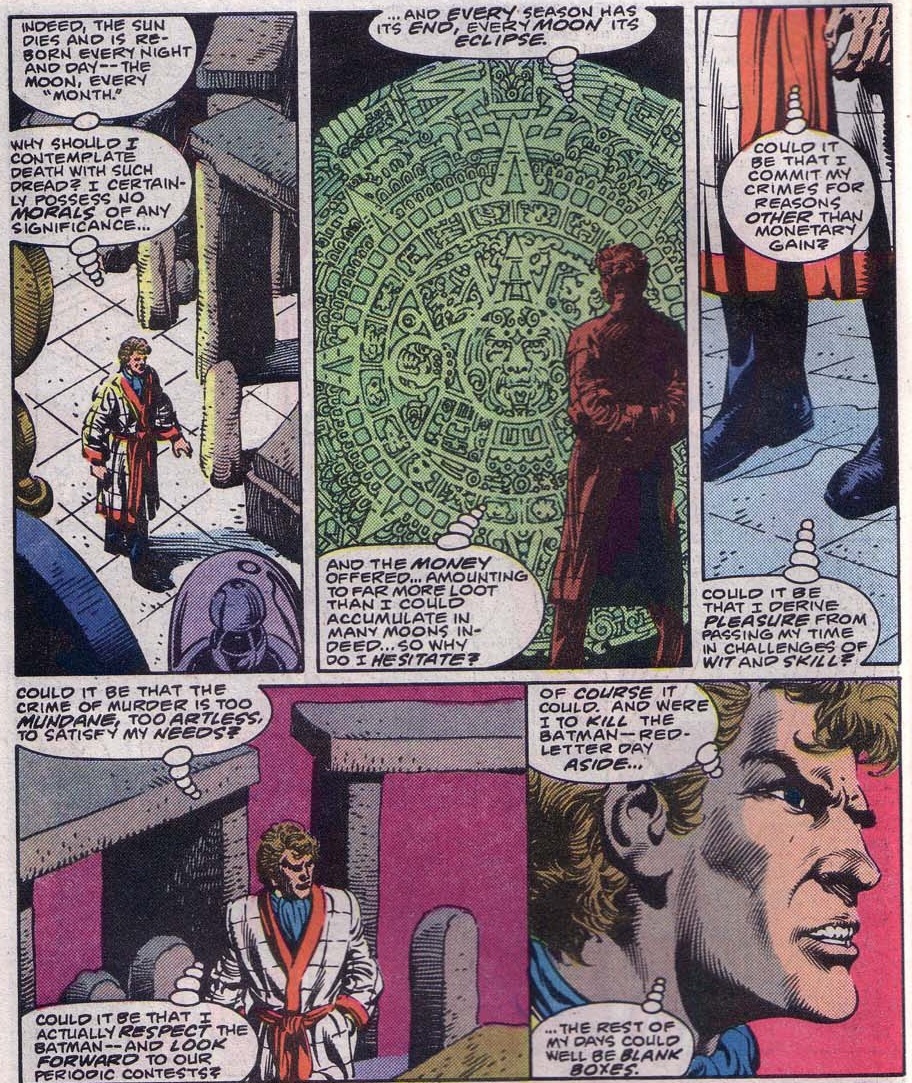

In ‘Broken Dates/The First Day of Spring/Day of Doom’ (Batman #384-385 and Detective Comics #551, cover-dated June and July 1985), Moench started by addressing head-on the obvious tension in Calendar Man’s characterization between his alleged financial motivation and his apparent infatuation with the artistic gamesmanship of crime. When the Monitor (in a brief tie-in to the Crisis on Infinite Earths crossover, at the time being set up across the various DCU titles) offered Julian Day a fortune to kill Batman, we got a glimpse of Calendar Man’s inner conflict:

Batman #384

Batman #384

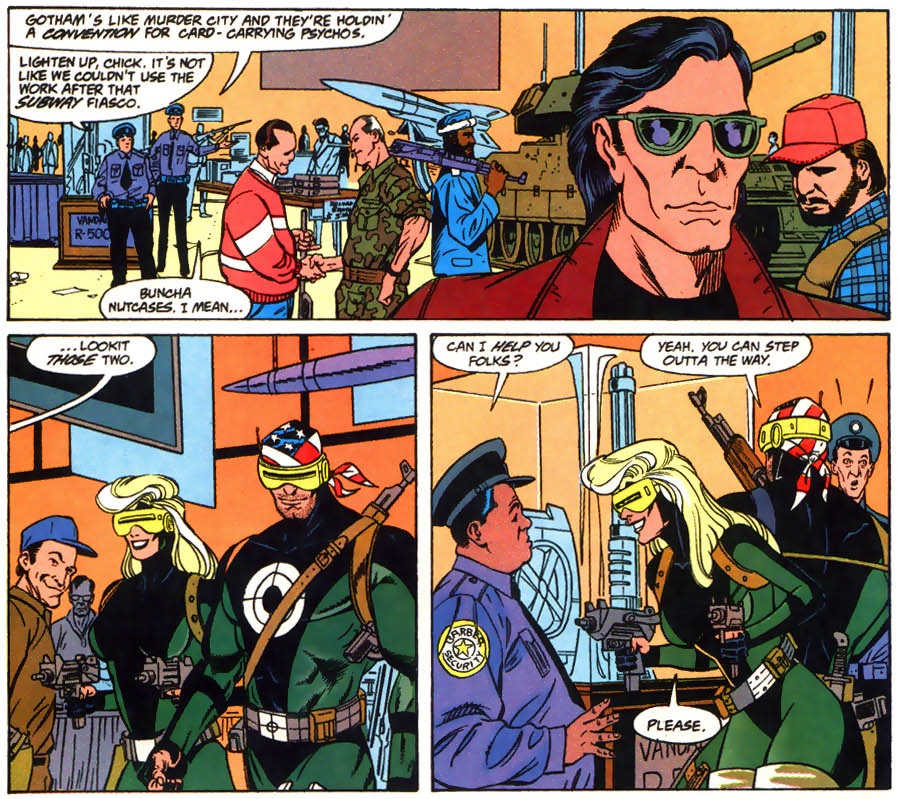

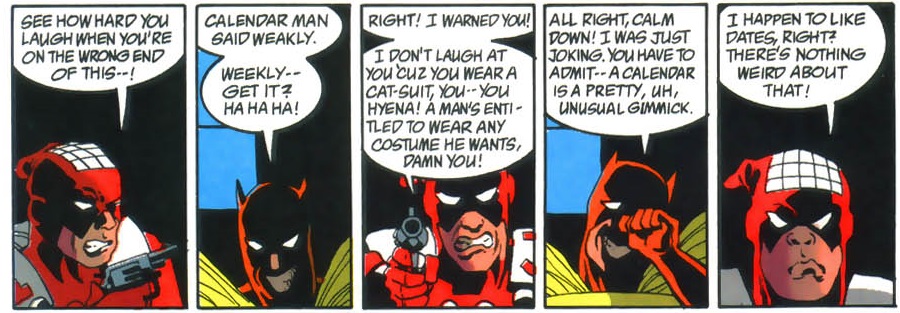

Understandably, Calendar Man didn’t have much of a presence in the grimmer, post-Dark Knight Returns era. When Alan Grant briefly brought him back in ‘The Misfits’ (Shadow of the Bat #7-9, December 1992-February 1993), alongside Killer Moth and Catman, the joke was precisely that these were losers among the villain community, aware that their reputation paled in comparison to that of the Joker and of the other big shots. In a desperate stab at relevance, they got together with a new player in town, Chancer (whose schtick was that he was quite lucky), and orchestrated the kidnapping of Commissioner Gordon, Mayor Armand Krol, and millionaire Bruce Wayne (thus frustrating my hopes, based on the arc’s title, that they would turn to music and form a Misfits cover band…).

Grant used Calendar Man to represent a more whimsical, gentler type of rogue, who at one point turned on Killer Moth because the latter tried to murder their victims instead of merely exchanging them for the ransom. That said, he was quite fed up with being made fun of:

Shadow of the Bat #7

Shadow of the Bat #7

I don’t have a problem with a more openly comedic take on Calendar Man, like the one we got in Shadow of the Bat or in his team-ups with other time-themed villains – Chronos and Clock King – in Team Titans #13-15 (October-December 1993) and Showcase ’94 #10 (September 1994). But I am sorry he eventually got stuck with the same costume, dropping one of his most amusing and distinctive attributes.

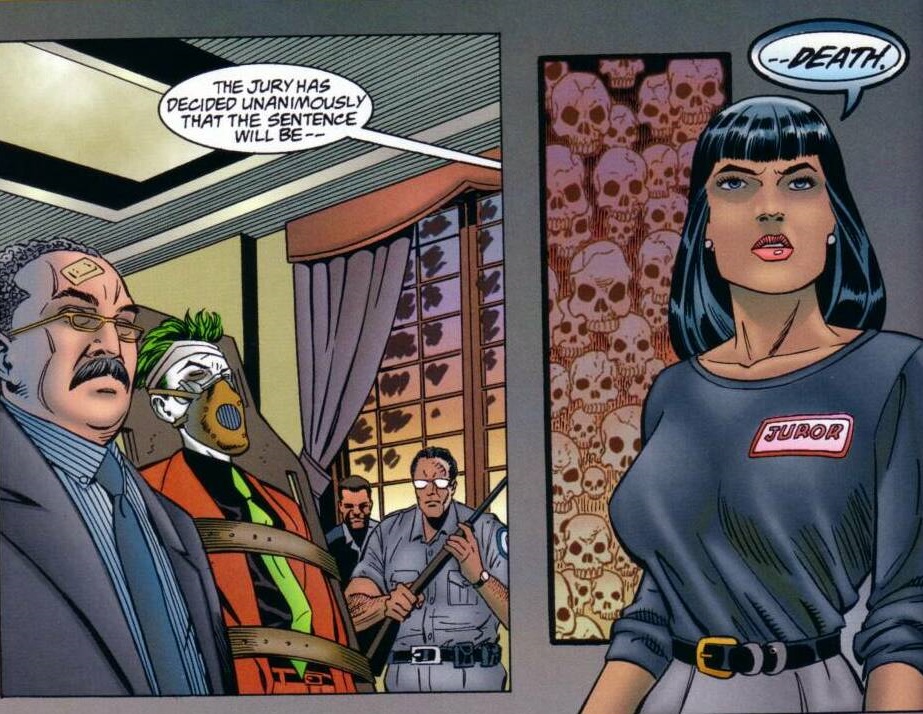

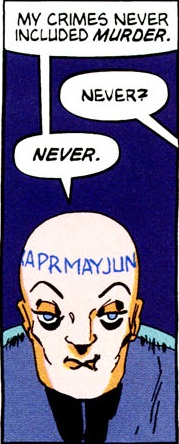

One major exception to the nineties’ lighthearted approach to the character came with 1997’s limited series The Long Halloween, which reinvented Julian Day as a Hannibal Lecter-type figure:

The Long Halloween #3

The Long Halloween #3

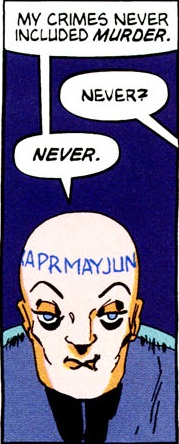

When revisiting this version of Calendar Man three years later, Tim Sale added a head tattoo:

Dark Victory #7

Dark Victory #7

The tattoo really stuck, showing up in most subsequent comics, including in the futuristic Batman Beyond, where Ryan Benjamin depicted an old, retired Julian Day (he also made sure to add a nod to Rick Hoberg’s calendar robe!). Even in Batman: Rebirth, where Scott Snyder and Tom King fully rebooted the whole concept of Calendar Man (he is now a serial killer with some kind of supernatural physiognomy, ageing in winter and then shedding his skin before being rejuvenated in spring), artist Mikel Janín kept a version of the head tattoo. That’s all fine, but I still miss the constant costume changes…

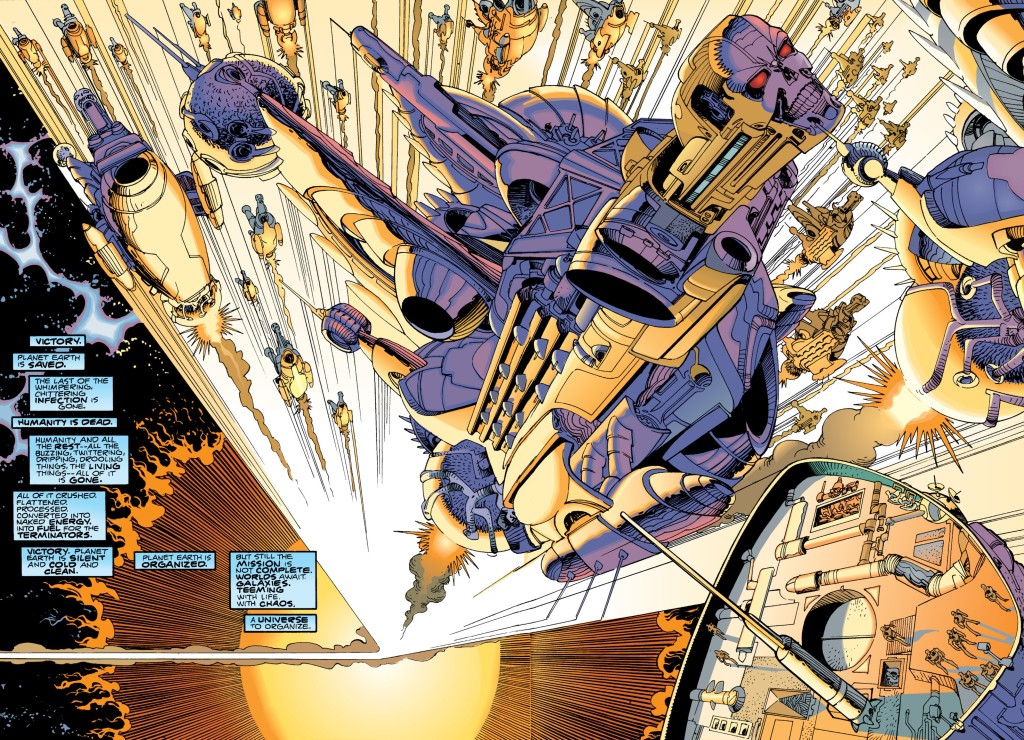

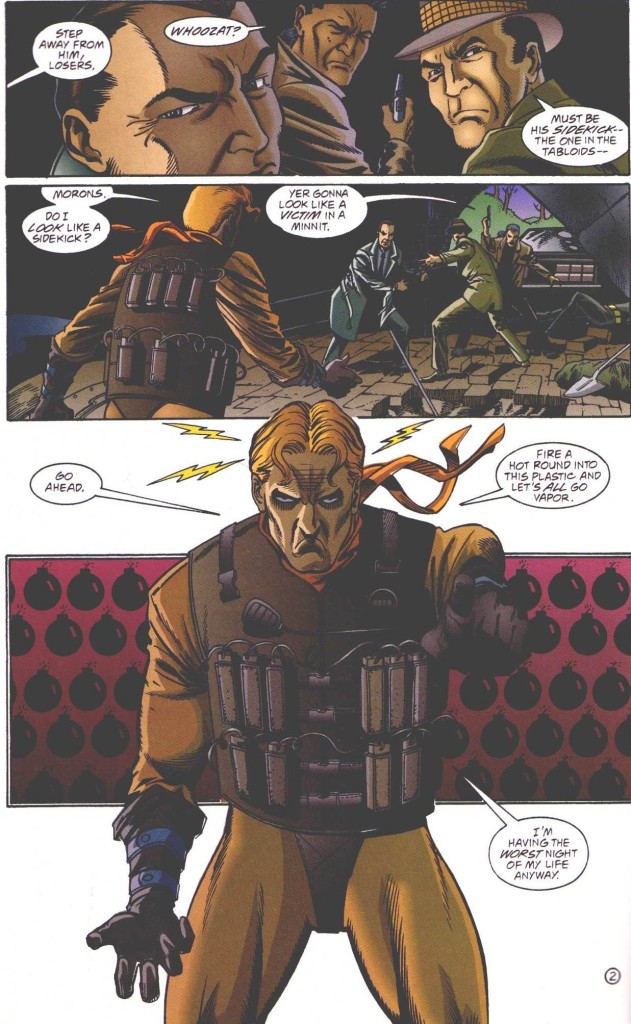

My favorite Calendar Man yarn in the past decades remains ‘All the Deadly Days’ (Batman 80-Page Giant #3, July 2000), in which Chuck Dixon had him go on a rampage over the fact that he had missed the turn of the millennium while in prison (I’ve written about it before). Dixon is a master at writing tales that capture the best of the past while also seemingly moving the characters forward… And like all the niftiest sequels (The Empire Strikes Back, Terminator 2, The Revenge of Frankenstein), his story here strikes a balance between the familiar beats that made the original so enjoyable and the boldness of taking the material in a new direction. And, sure enough, it features a new outfit, clearly designed by Mike Deodato to evoke the type of clothing style trending in post-‘Image explosion’ mainstream superhero comics at the time, complete with broad metallic shoulder pads, a humongous cloak, and the obligatory pouch:

Batman 80-Page Giant #3

Batman 80-Page Giant #3

Another noteworthy set of fashion-conscious criminals are the trio of Dragon Fly, Silken Spider, and Tiger Moth, whose connections to the arts were prominent from early on. Created by Robert Kanigher and Sheldon Moldoff in Batman #181 (June 1966), the first time we saw these three was actually as provocative posters in a pop art exhibition:

Batman #181

Batman #181

Although Moldoff – inked by Joe Giella – did a wonderful job of coming up with distinctive designs that worked the motifs in their names into sexy outfits, Dragon Fly, Silken Spider, and Tiger Moth weren’t meant to stick around. Instead, the whole point of the issue was to set them up as major public enemies only for them to be rapidly overshadowed by a debuting Poison Ivy. I always felt like there was an untapped story there, though: how did these three make it to the top?

Using them merely to establish Poison Ivy’s ‘ultimate femme fatale’ status wasn’t just an efficient storytelling device, but also a fairly misogynous one, preying on the trope of petty female competition while characterizing all the women in the comic as divas driven by vanity. Wisely, when Alan Grant reworked Ivy’s first encounter with the Caped Crusader, in Shadow of the Bat Annual #3 (January 1995), he completely abandoned this plotline. Grant nevertheless made a point of including a nod to the original tale in the form a small cameo, turning the trio into rock singers:

Shadow of the Bat Annual #3

Shadow of the Bat Annual #3

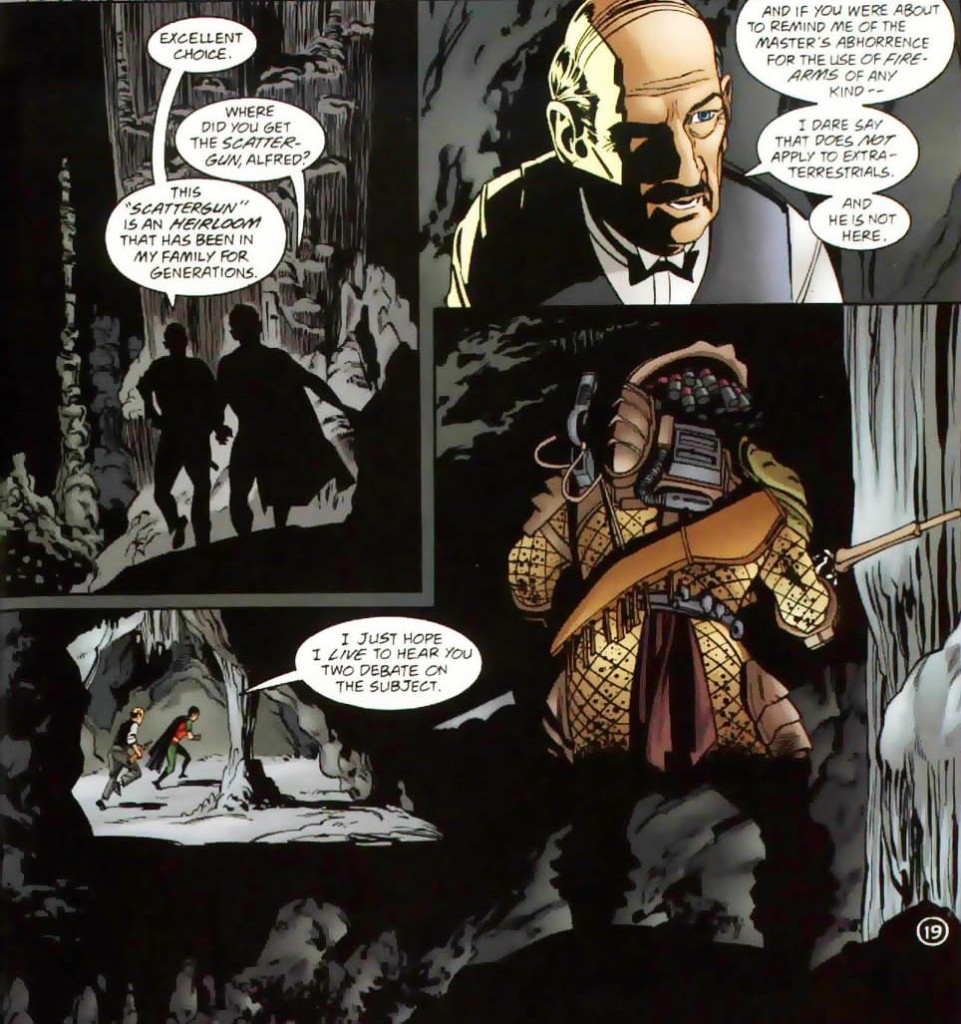

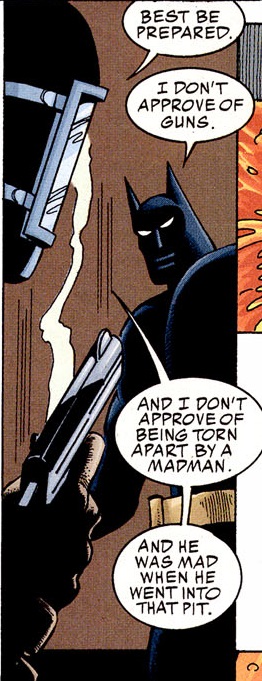

In turn, Grant Morrison – the other Scottish Grant who left an indelible mark on Batman comics – took a different route in 2008’s crossover The Resurrection of Ra’s al Ghul, where Dragon Fly, Silken Spider, and Tiger Moth were recruited for the League of Assassins by Talia al Ghul. They got slightly more developed traits this time around: Silken Spider was now able to perform mass hypnotism (through an intoxicating nerve agent) and Tiger Moth came across as an all-American gun nut.

In a typical Morrison move, the comic fuzzily blended past continuity, alluding both to the trio’s original story (Dragon Fly complained that she used to be Public Enemy Number One, at least ‘on a series of campy pop art posters’) and to their musical career (Talia told them they weren’t ‘backstage in Vegas’ anymore). It also did that postmodernist thing of reproducing old tropes under an ironic guise that is probably not to everyone’s liking, as the three ladies all sounded hilariously bitchy.

Tony Daniel’s redesign of their costumes wasn’t as keen as Sheldon Moldoff’s (they now had more of a Vampirella sexploitation vibe), but at least they looked more ethnically diverse. I quite like this panel giving us a glimpse of their pre-act stance:

Batman #670

Batman #670

Like in their debut tale, Dragon Fly, Silken Spider, and Tiger Moth played a pretty marginal role in the overall plot of The Resurrection of Ra’s al Ghul, their main function being essentially that of a cheeky Morrisonian throwback to the franchise’s convoluted history. In his contribution to the crossover, Paul Dini had them committed to Arkham Asylum after getting poisoned, with a close-up of a doctor (sort of looking at the readers) declaring: ‘I don’t know if they’ll ever be fully functional again.’

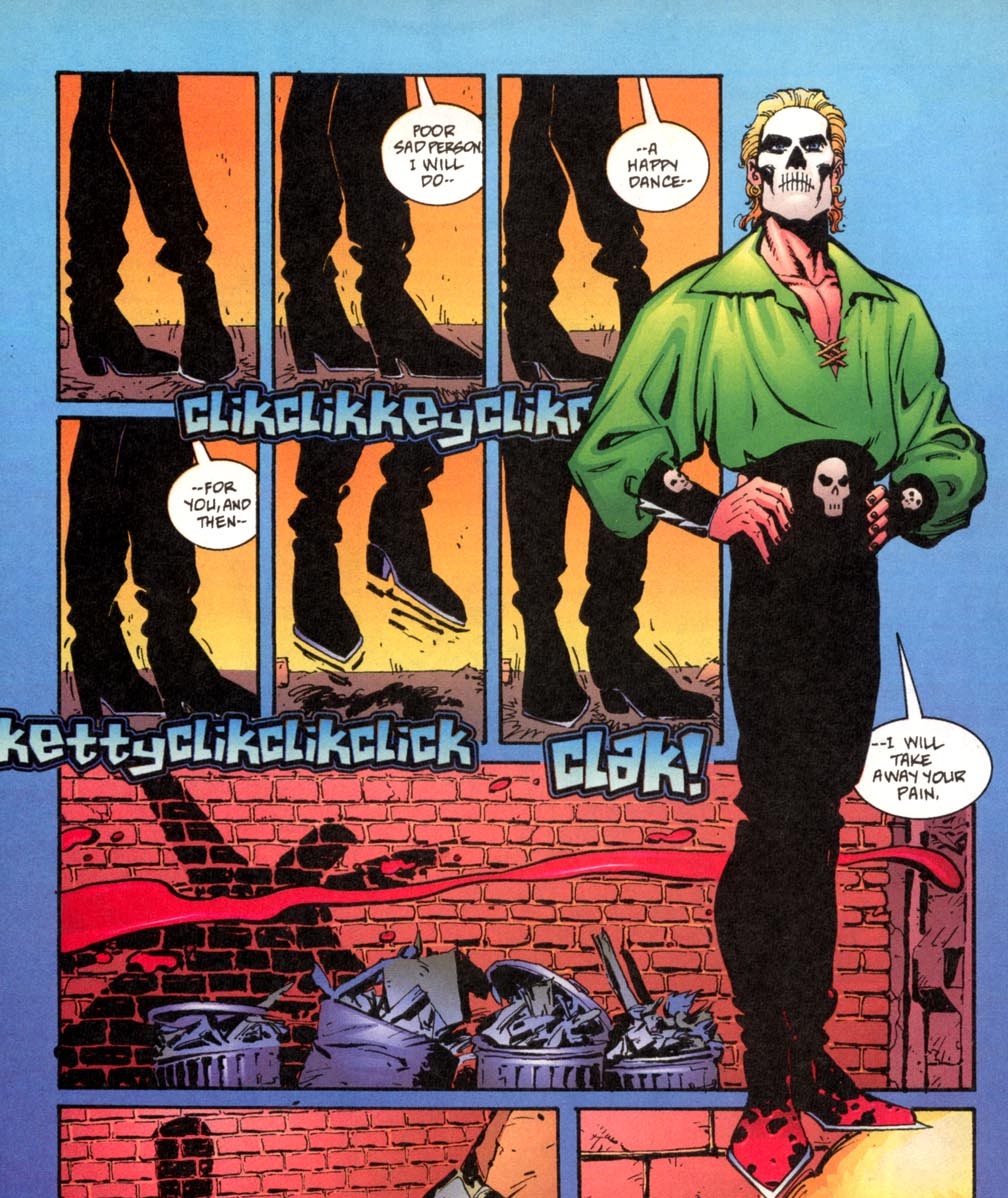

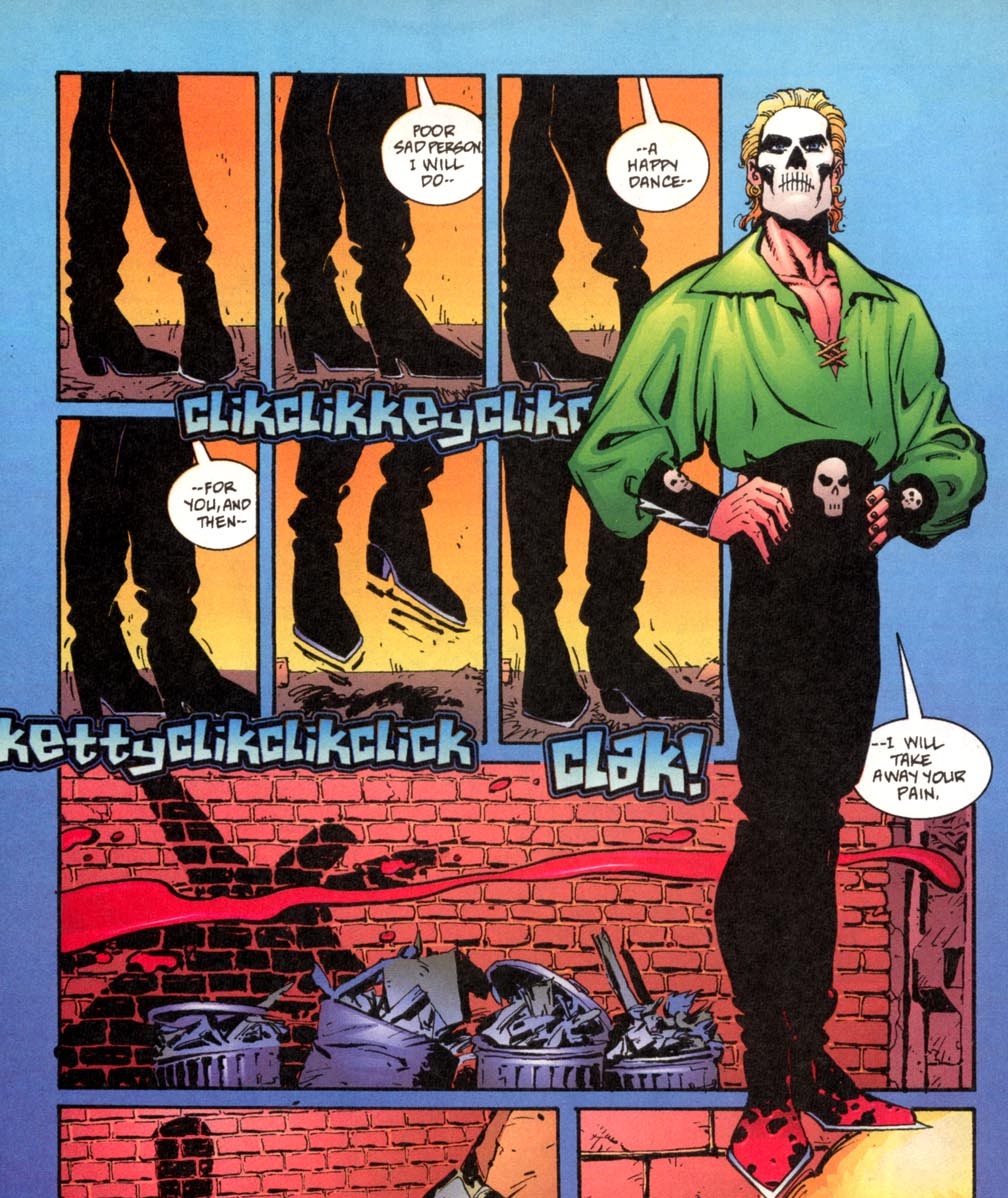

I don’t know either. Perhaps there is no hope for those three, although I wouldn’t mind a musical team-up between them and the aforementioned Misfits cover band, with a choreography by the Death Dancer:

Azrael: Agent of the Bat #54

Azrael: Agent of the Bat #54