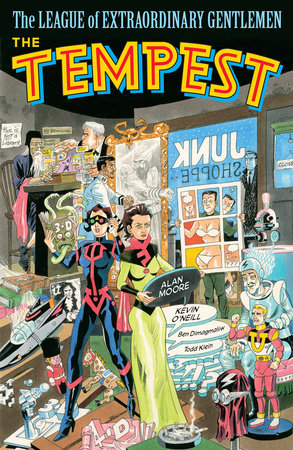

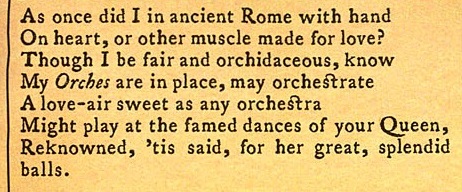

If Master Race and other stories was Gotham Calling’s 2018 book of the year, this time around that questionable honor goes to The Tempest, the collection that marks the ending – twenty years after the first issue came out – of the violent, depraved, and flawed-yet-very-entertaining metafictional series The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. Before going into The Tempest in some depth, though, let us look back on one of the medium’s most ambitious narrative experiments.

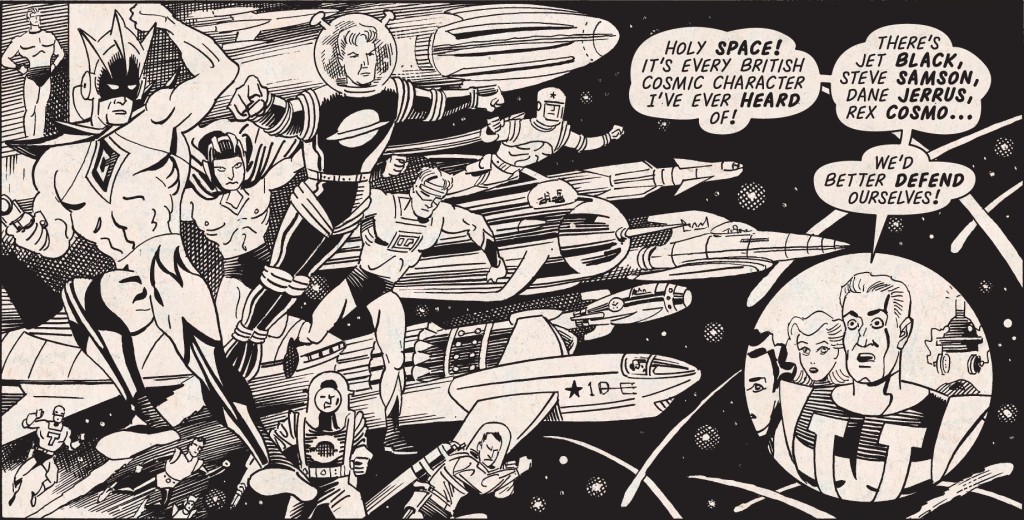

LOEG’s twofold premise is that 1) every single character in the series – including background extras – is borrowed from other works of fiction (mostly genre literature) and 2) every major literary work kind of fits into the same byzantine continuity. Because the comic is drawn by Kevin O’Neill, the art is gorgeously stylized. And because the whole thing is written by Alan Moore, you can stretch the definition of ‘major literary work’ to include pretty much everything you can think of, whether it’s Homer’s Odyssey or Winnie-the-Pooh. The result is basically an extreme version of the Wold Newton Universe.

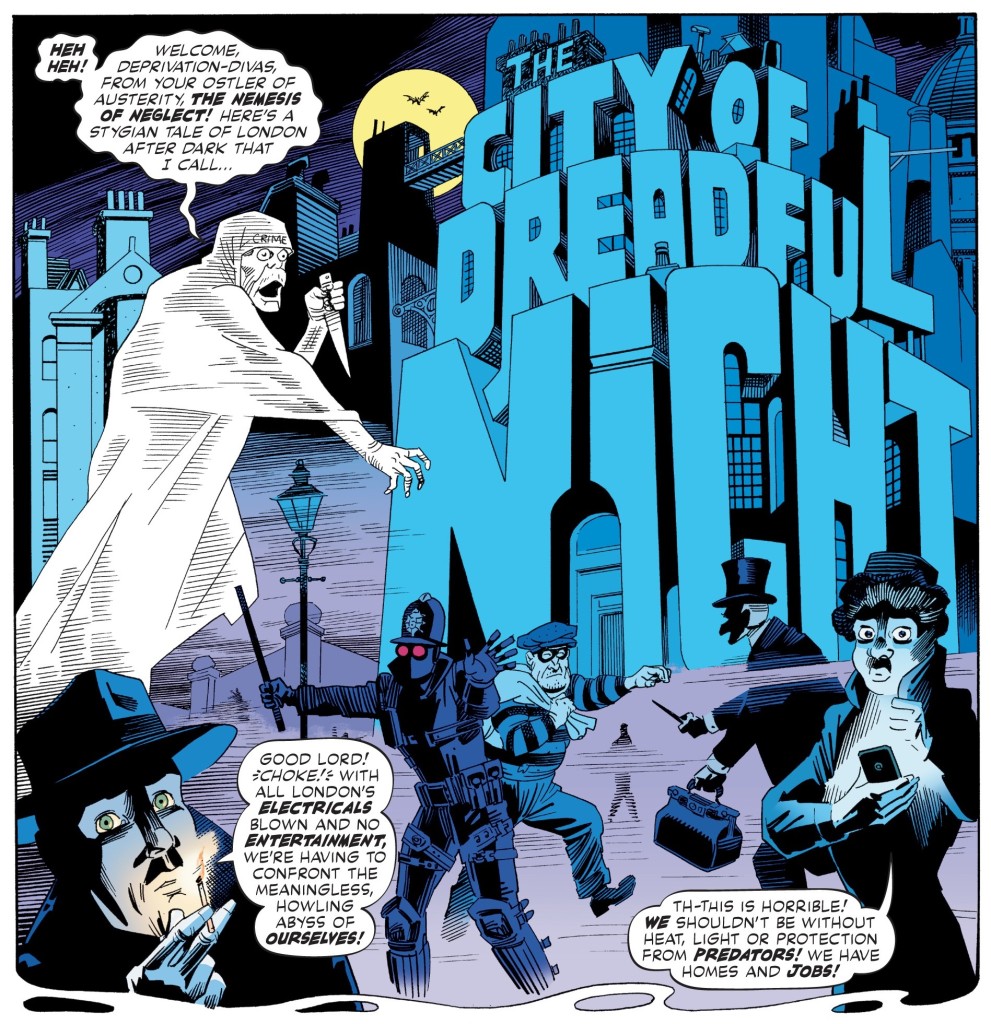

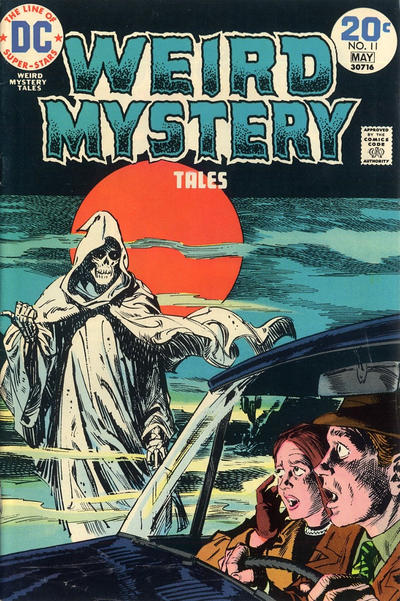

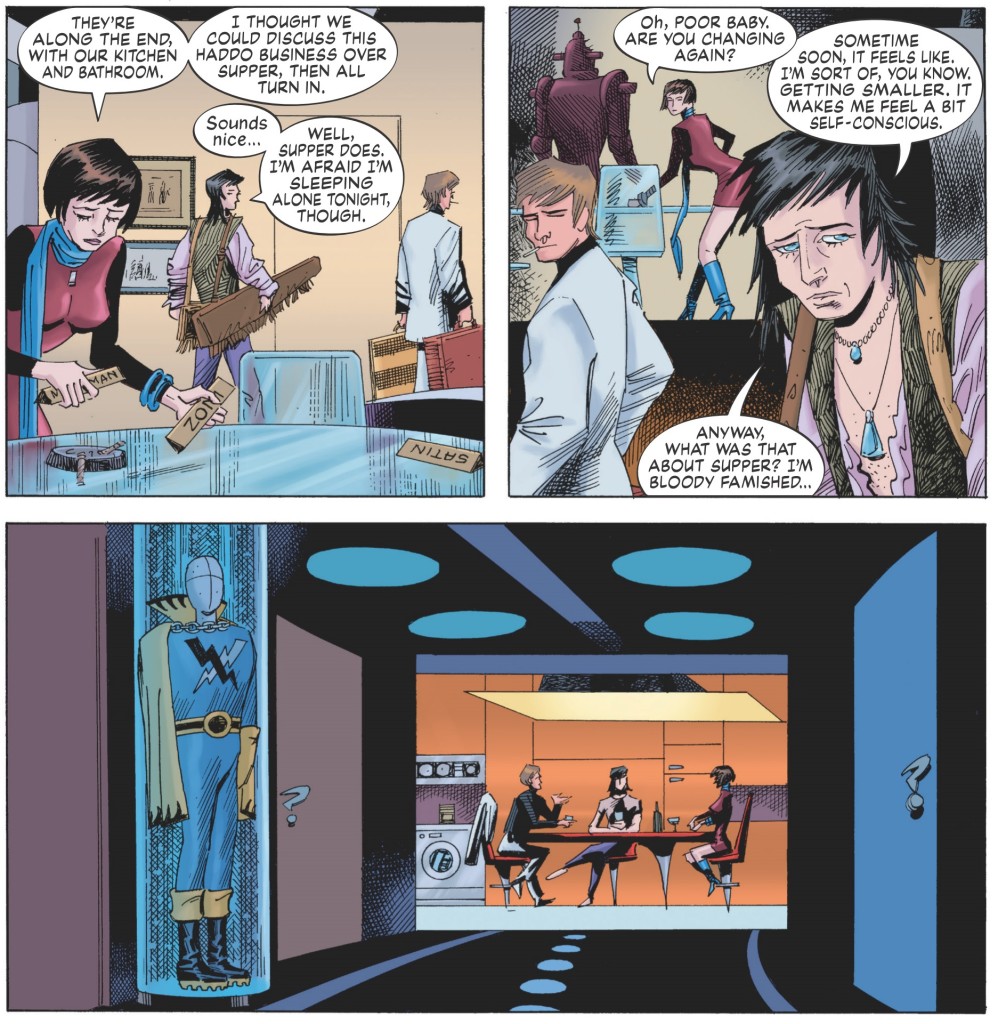

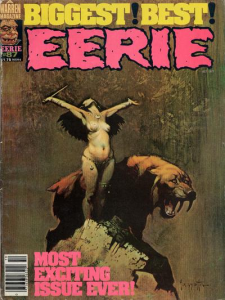

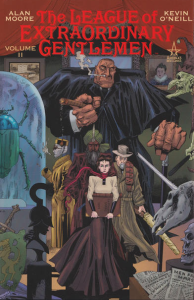

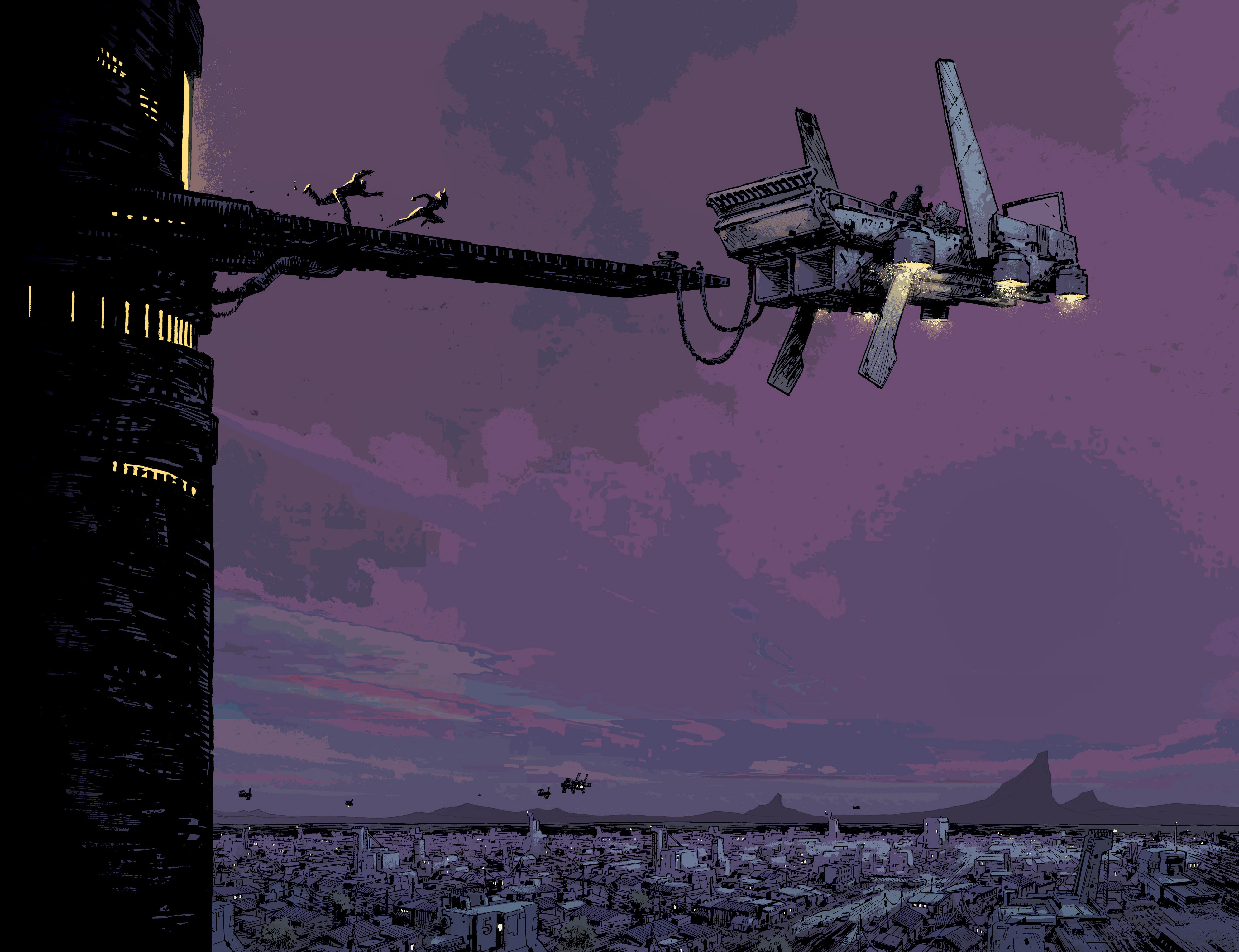

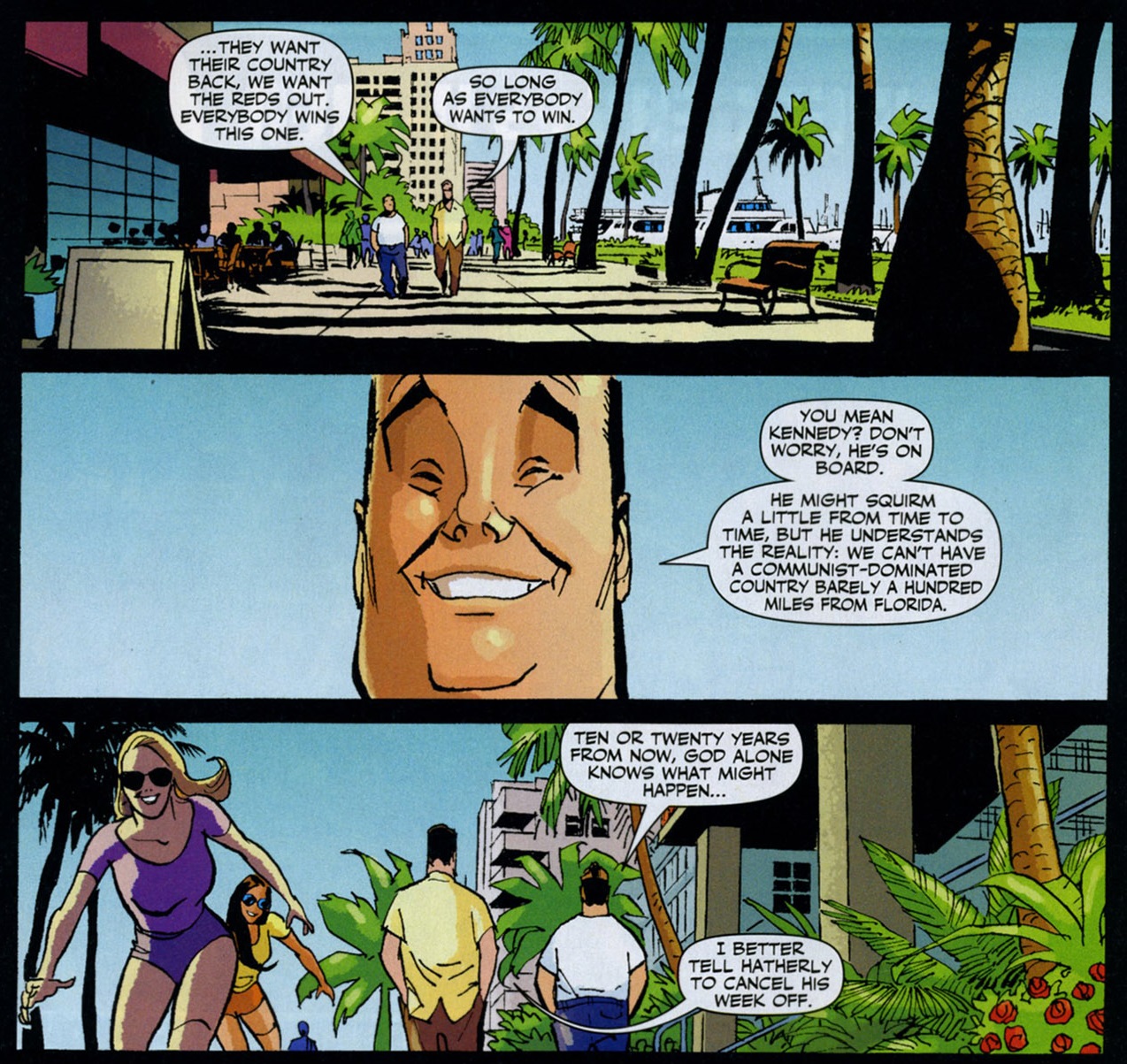

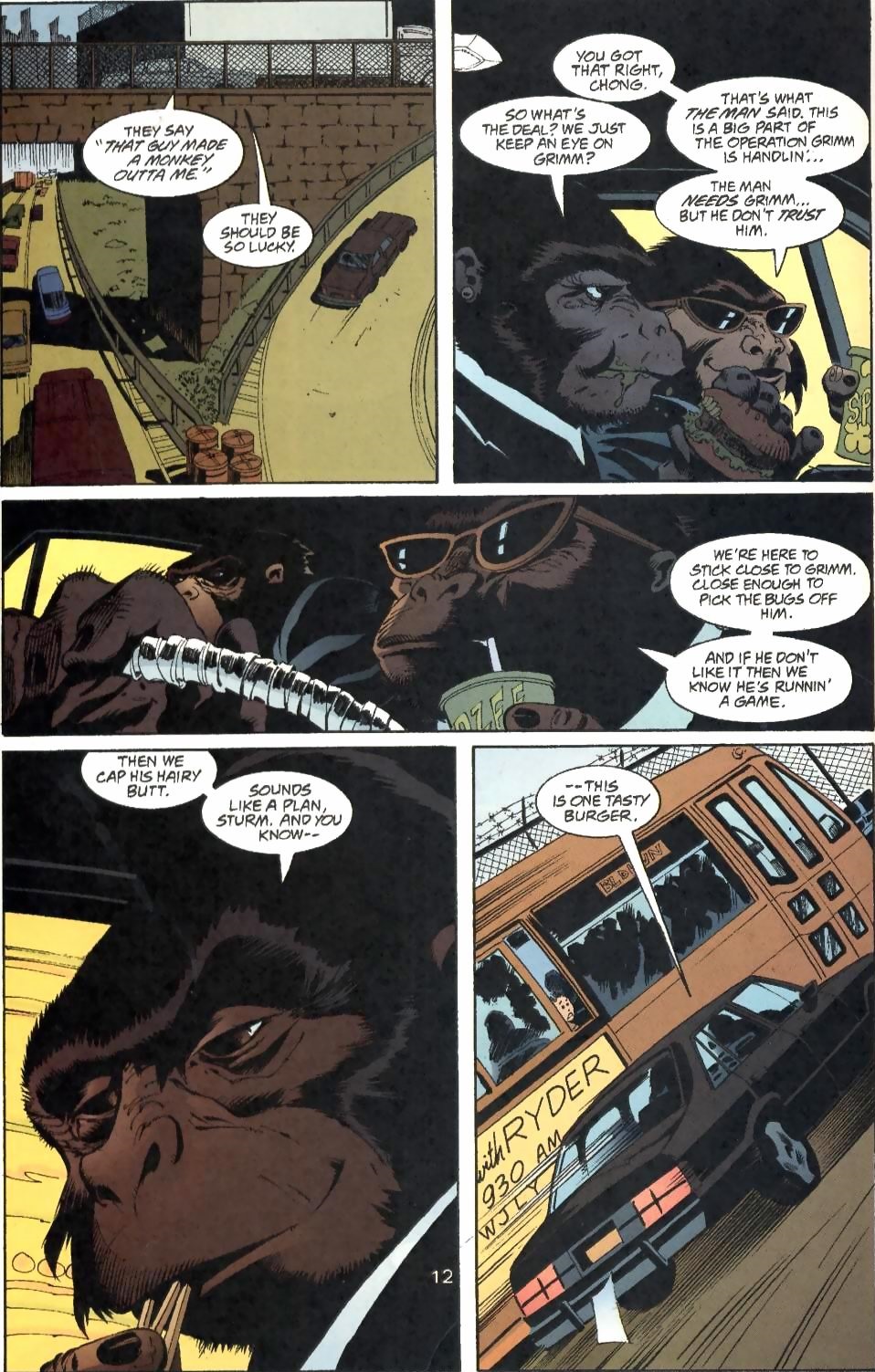

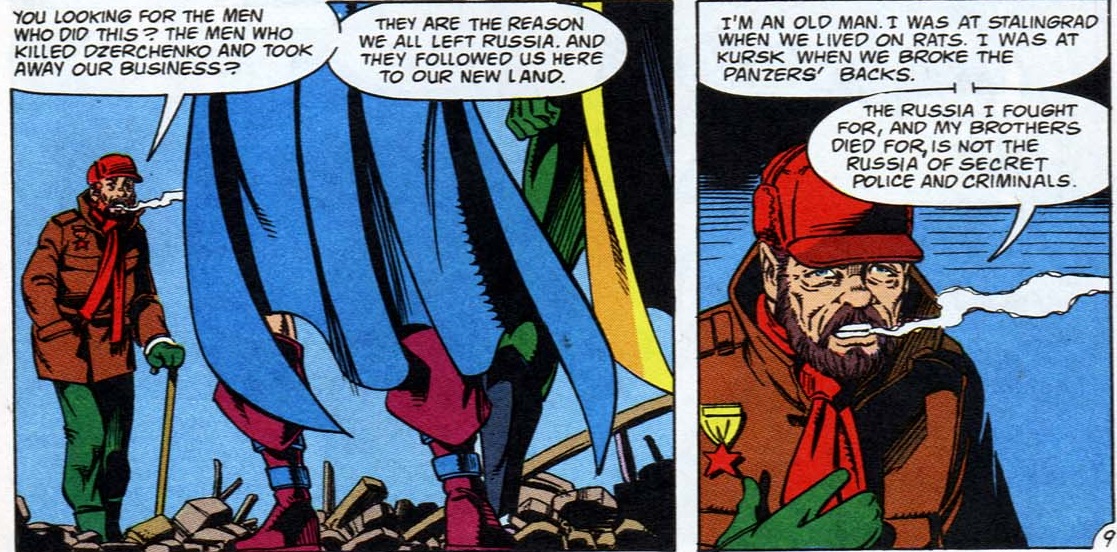

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (v2) #5

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (v2) #5

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen is one of Alan Moore’s most contested masterpieces. All of his greatest works (Watchmen, V for Vendetta, From Hell, Miracleman, Swamp Thing) are challenging reads in terms of form and content, but they are also indisputably rewarding to anyone willing to engage with them. While the same can be said about LOEG, several critics seem frustrated over the fact that the ratio is somewhat different, i.e. even if you can get a lot out of it, there are just so many damn references – and some of them so obscure – that you’re not likely to grasp *every aspect* of the series, no matter how much effort you put in! (This penchant for ever-more demanding eclecticism has become a staple of Moore’s later period, reaching an apex in his colossal novel Jerusalem.)

I can see the point of that criticism, especially from readers used to fully decipherable books, but I don’t identify with it – for me, LOEG is a comic that keeps on giving, not only because it is rich with clever details and captivating themes, but also because I find myself revisiting bits of it with renewed appreciation every time I come across any of the many works referenced in the series. Like the fact that some of the dialogue is in untranslated foreign languages (ranging from Dutch to Punjabi, plus a made-up Martian language that you have to decipher with the help of a mirror), the endless referentiality is all part of the challenge!

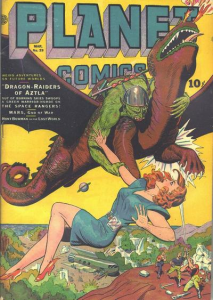

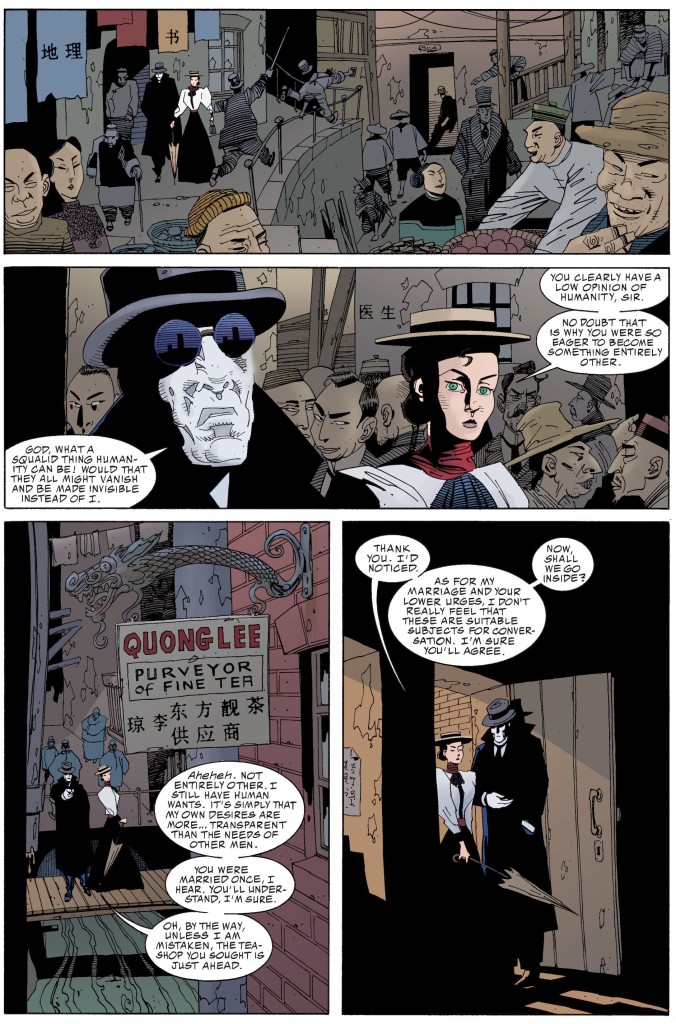

Ironically, some of the critics’ anger may derive from the fact that LOEG did ease readers in with a rather smooth start, ushering in misleading expectations… The first couple of volumes were mostly straightforward adventure tales about a secret team of British agents in the 1890s, with a neat steampunk vibe, albeit peppered with Moore’s flair for deconstructing archetypes (the leading characters actually spent a lot of the time at each other’s throats). In line with the rest of the America’s Best Comics line, in which Moore mined literary traditions beyond superheroes for different approaches to heroic fantasy (Tom Strong drew on the pulps, Promethea on mythology, Greyshirt on Eisner’s The Spirit…), LOEG was essentially a revisionist homage to the rousing yarns of the eighteen hundreds.

It also helped that the members of the original roster – Mina Murray (from Dracula), Captain Nemo (from 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and The Mysterious Island), Allan Quatermain (from King Solomon’s Mines and its sequels), Henry Jekyll/Edward Hyde (from Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde), and Hawley Griffin (from The Invisible Man), led by a character from the Sherlock Holmes books – were generally well-known in Western pop culture. The same goes for the (admittedly nerdier) choices in the delightfully ornate prose story in the back matter, with Quatermain meeting John Carter of Mars and the protagonist of H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine, as well as Randolph Carter (from H.P. Lovecraft’s stories). The second volume revolved mostly around H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds, eventually crossing over with the same author’s The Island of Doctor Moreau.

All in all, there was still a relatively limited amount of luggage required to follow the main plot in these first couple of volumes. The remaining references then worked as a bonus – for instance, you didn’t have to be familiar with Edgar Allan Poe’s ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ or Jules Verne’s Five Weeks in a Balloon beforehand, but, if you were, you’d get even more enjoyment out of the proceedings. And although the extensive prose pieces in the back matter already pointed to Moore’s increasing ambition of building a coherent universe out of everything he’d ever read, I guess fans didn’t mind as long as this didn’t get in the way of O’Neill’s pretty pictures. After all, these were two masterful storytellers who knew just how to frame and pace set pieces for maximum effect (like the way they kept giving us a sense of Griffin’s movements while keeping him invisible, without resorting to the usual ‘semi-transparent’ effects).

The fact that the main cast and concepts were in the public domain and had already been popularized in countless media adaptations made them accessible even to people who hadn’t actually read the classics, allowing the series to build up on previously established characterization.

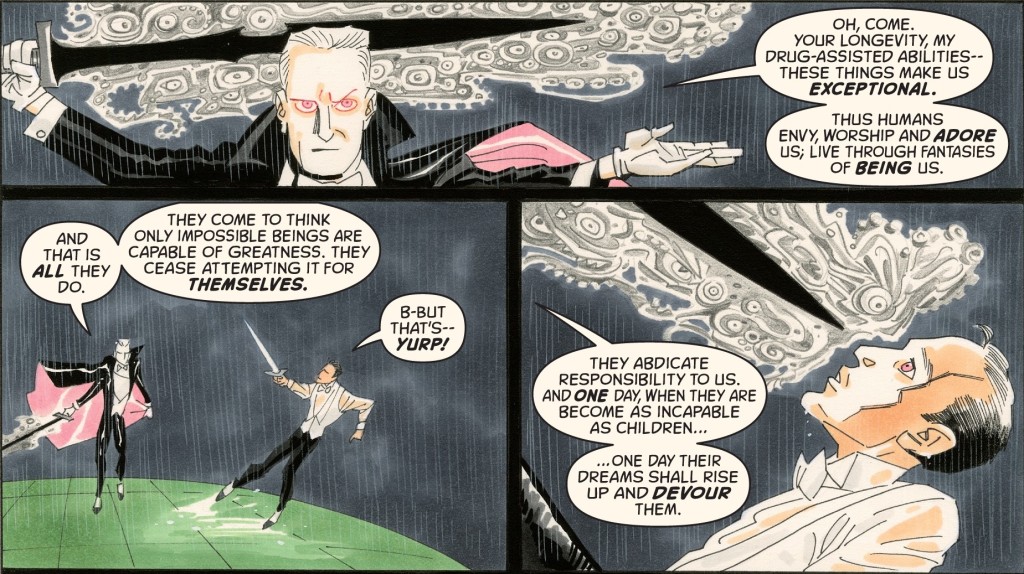

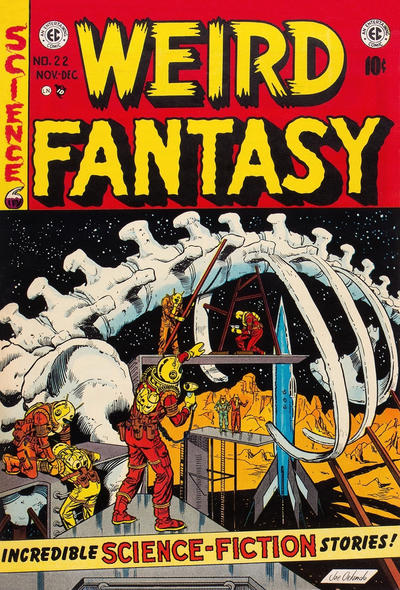

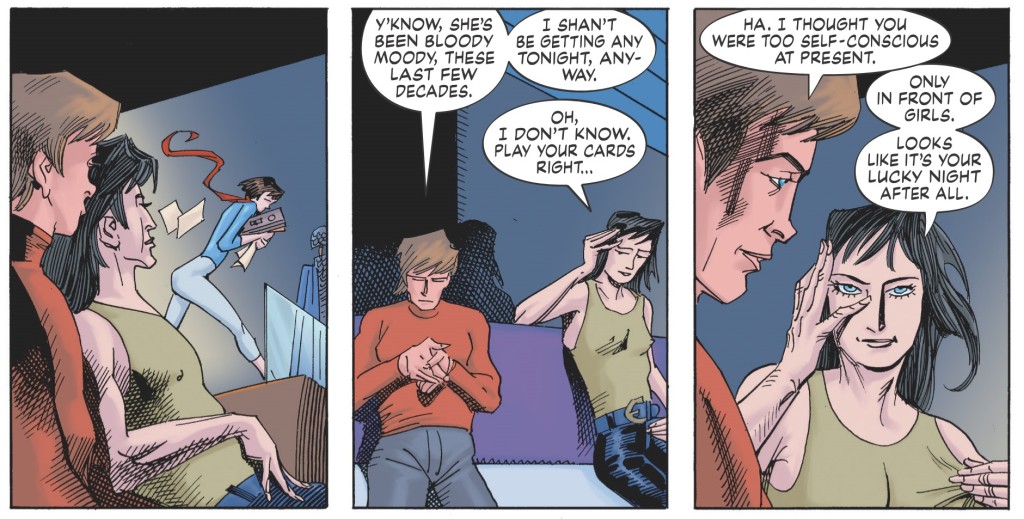

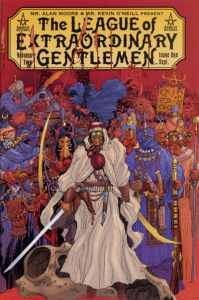

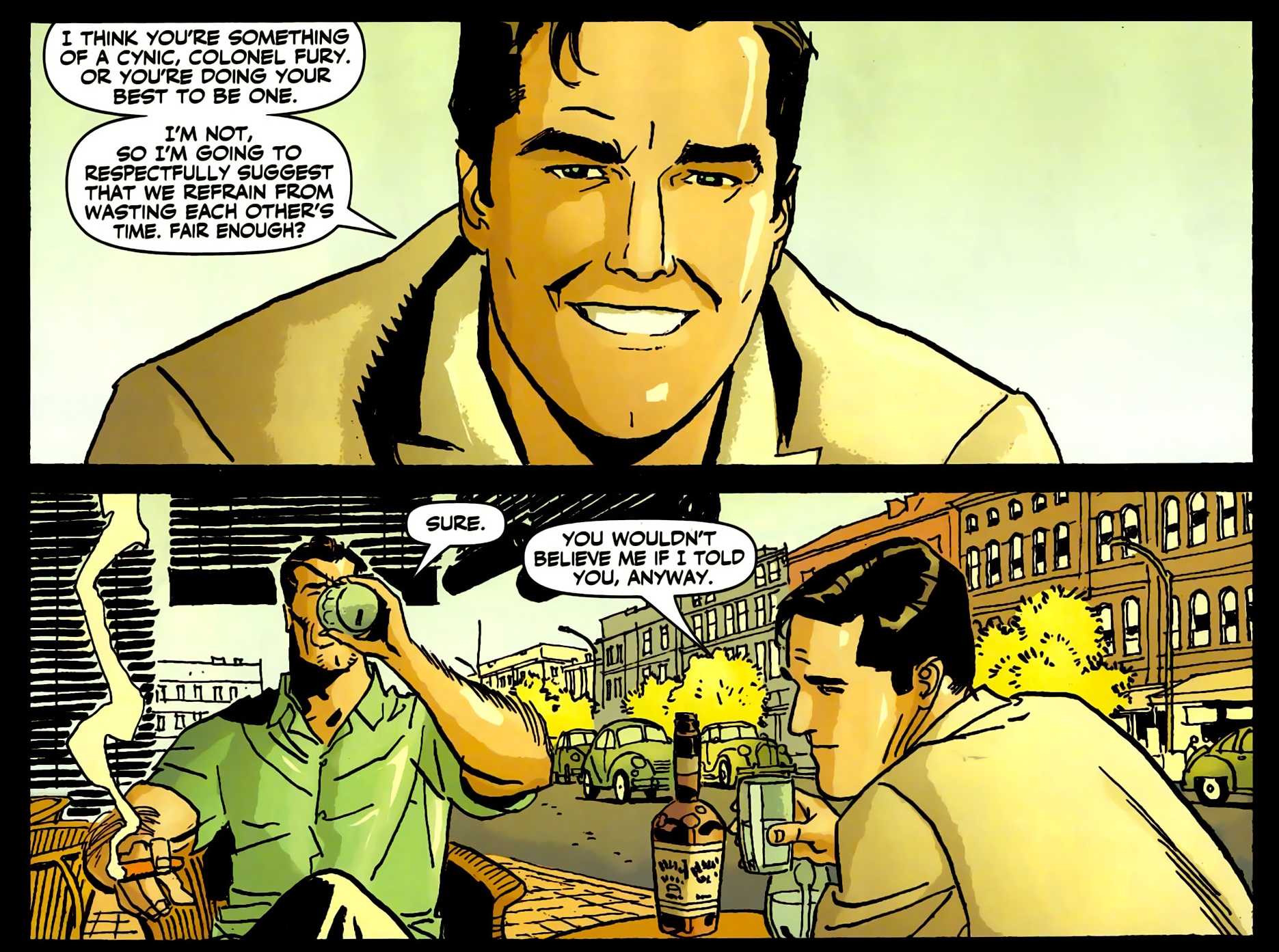

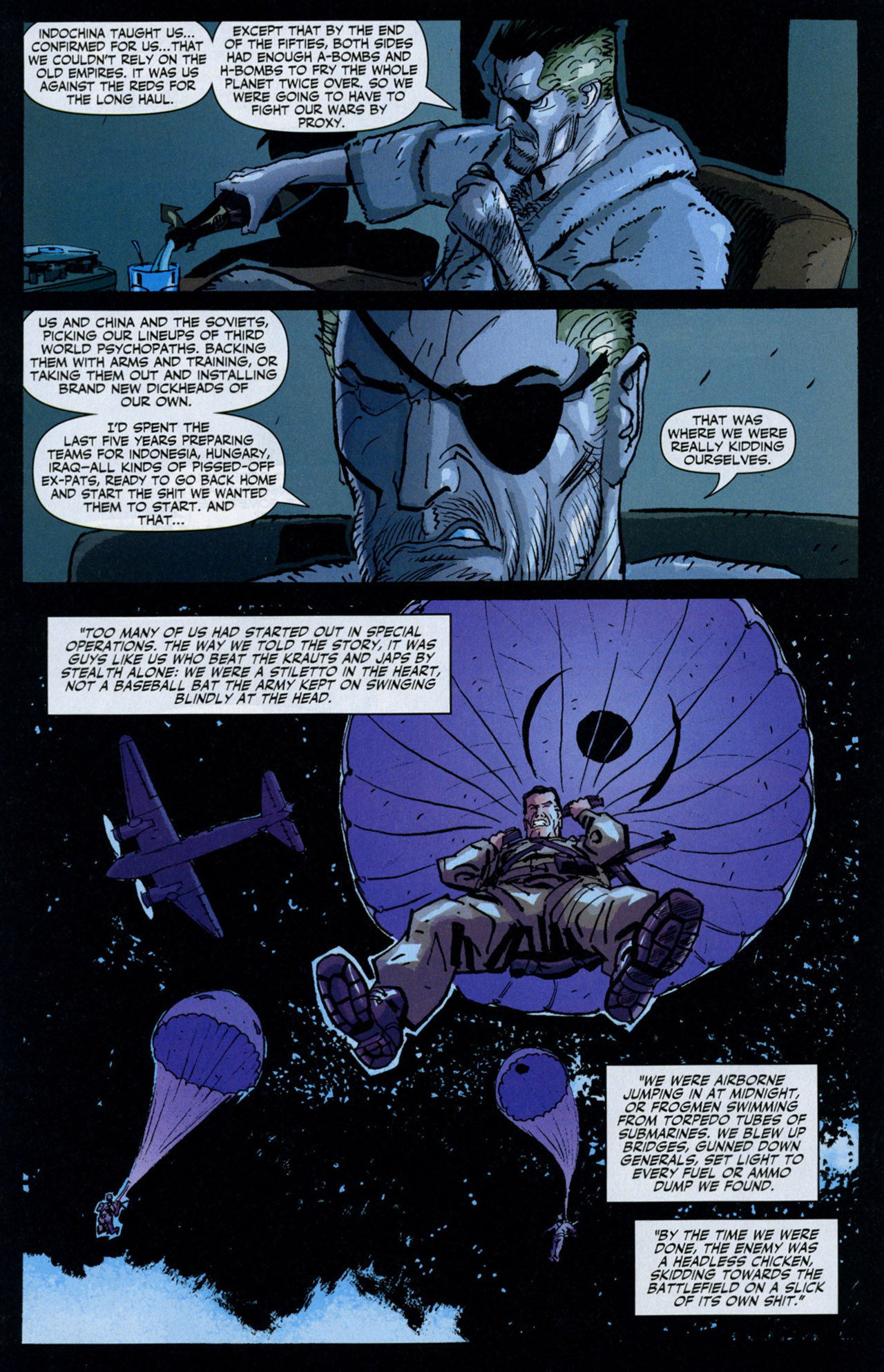

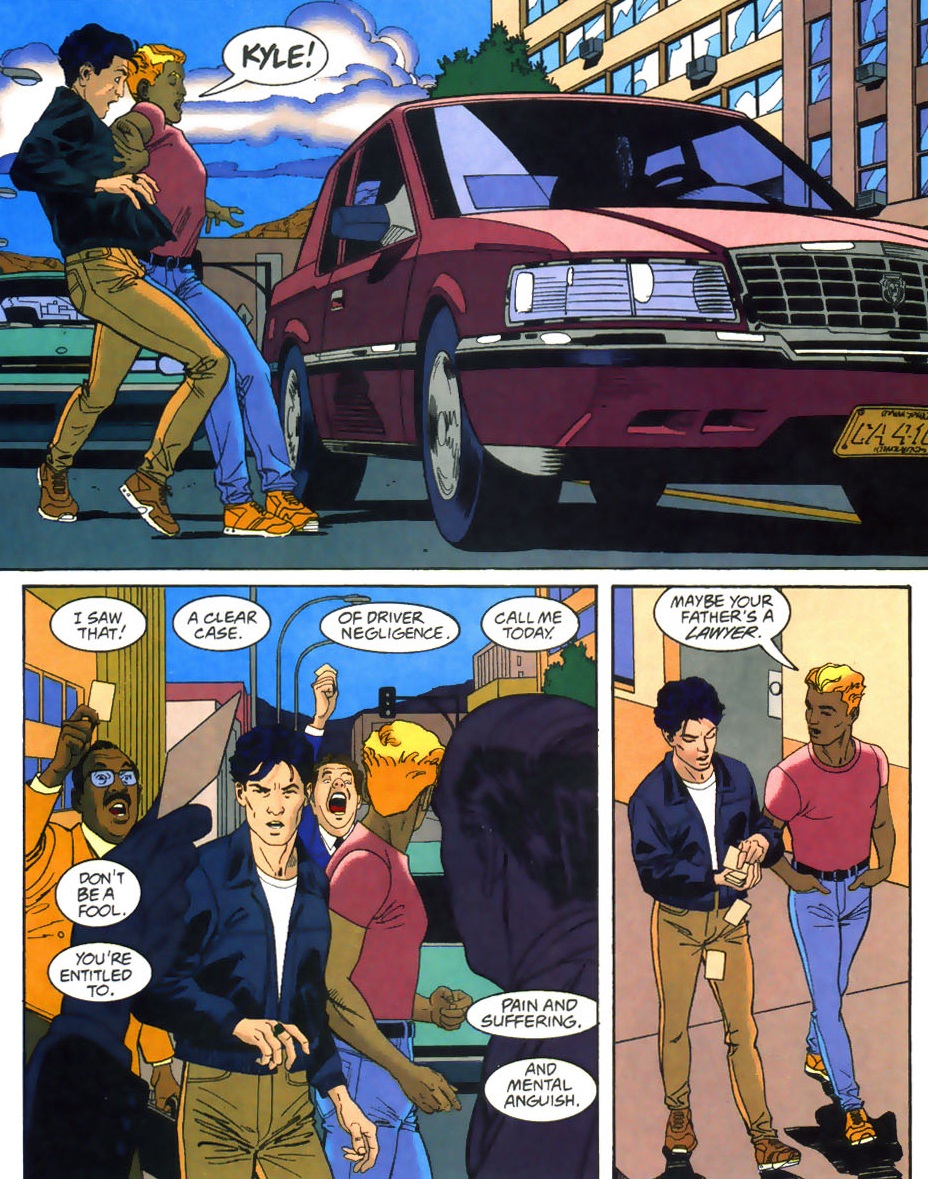

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen #3

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen #3

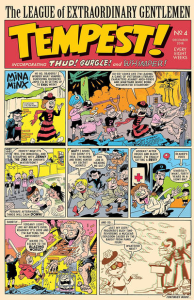

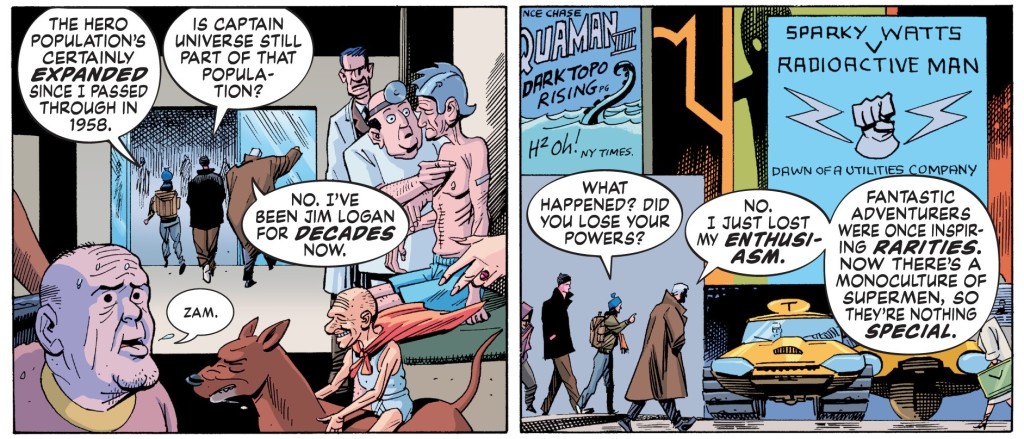

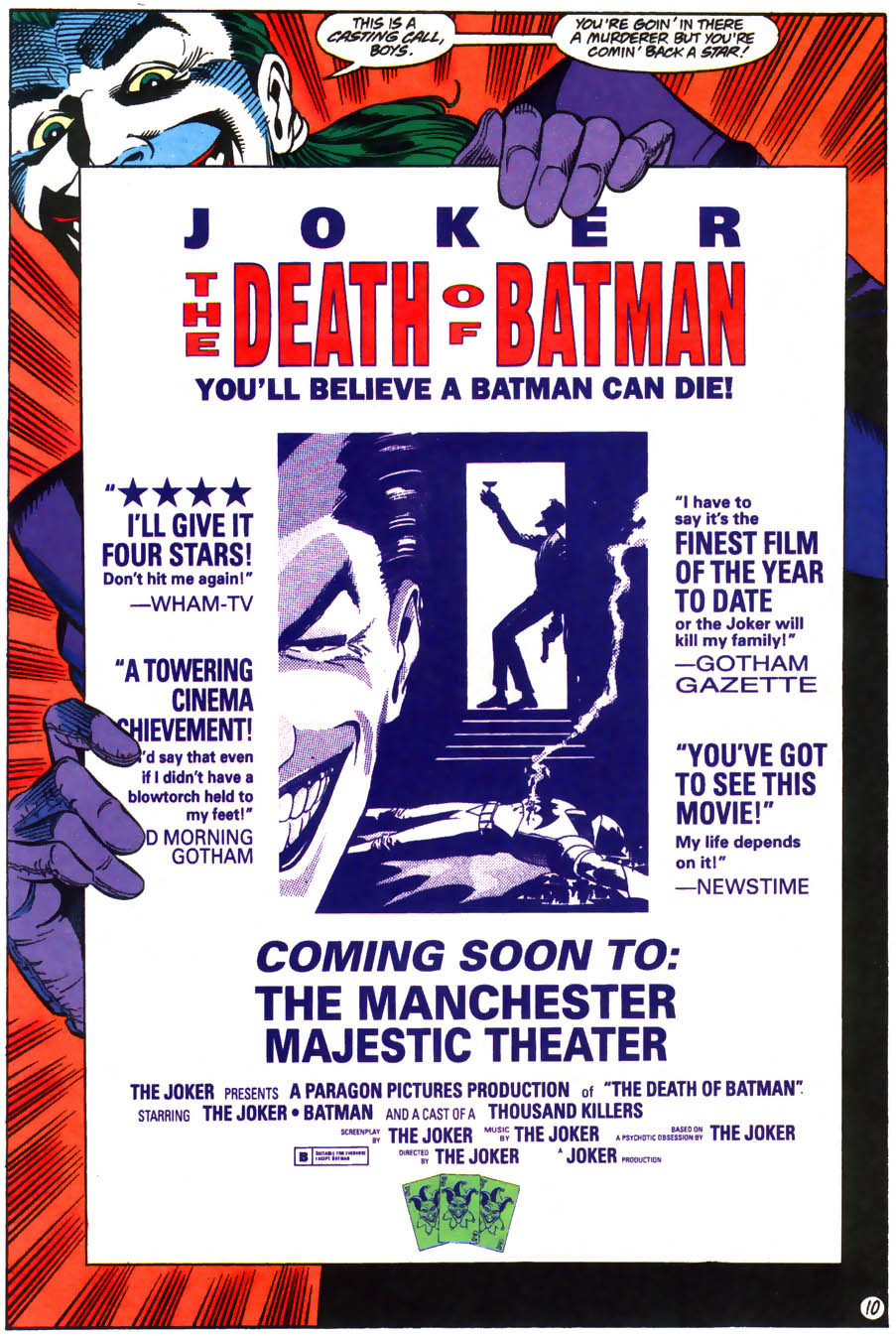

Although LOEG went into some seriously dark places (especially regarding Griffin and Hyde), the comic was also, from the outset, unabashedly funny. Besides the many in-jokes and Easter Eggs (Moore’s scripts must have been as detailed as those he did for Top 10), the credits, blurbs, and extra material framed the comic as an actual ‘Boys’ Picture Monthly’ published in late 19th century England, including tongue-in-cheek warnings such as ‘Mothers of sensitive or neurasthenic children may wish to examine the contents before passing it on to their little one, removing those pages which they consider to be unsuitable.’ Some issues even contained authentic vintage advertisements, including one for a vaginal syringe called Marvel which DC recalled out fear that it could trigger litigation from Marvel Comics (this was one of the reasons Moore shifted LOEG to a different publisher, along with an incident regarding the by-all-accounts dumbed-down film adaptation of the comic).

The pastiche in these extras often veered into outright absurdist humor. This is from the authors’ bio section in one of the collected editions: ‘MR. KEVIN O’NEILL commenced his career as a pugilist in 1859. Due to excessive drinking and repeated cerebral splintering during an early bout with Walter Phibbs, the Widnes Goliath, O’Neill passed into an insensible state from which he was never fully to awaken. However, in 1885, doctors discovered that by attaching galvanising cables directly to the comatose prize-fighter’s brain, his right hand could be made to delineate exquisite and fanciful illustrations, such as his well-known series “Modern Times, or, The Progress of a Scented Nonce,” and, of course, his scandalous “Queen Victoria and Emily Pankhurst Girl-on-Girl Novelty Flipbook.”’

In particular, Moore had a blast poking fun at the era’s rampant racism and sexism. One of the running jokes involved the contrast between, on the one hand, the over-the-top misogyny displayed by most of the cast (and by the Victorian narrator) and, on the other hand, the fact that Mina Murray was clearly the most capable character around. Indeed, apart from her and the opium-addicted Quatermain, practically everybody was a psycho…

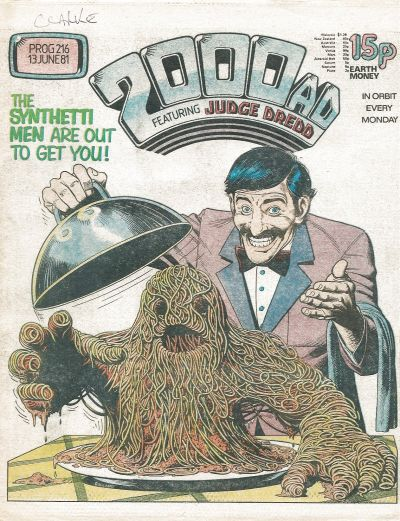

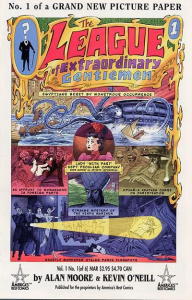

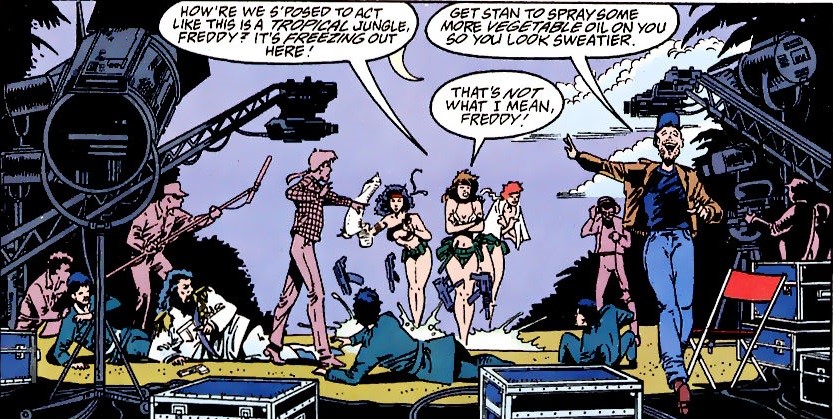

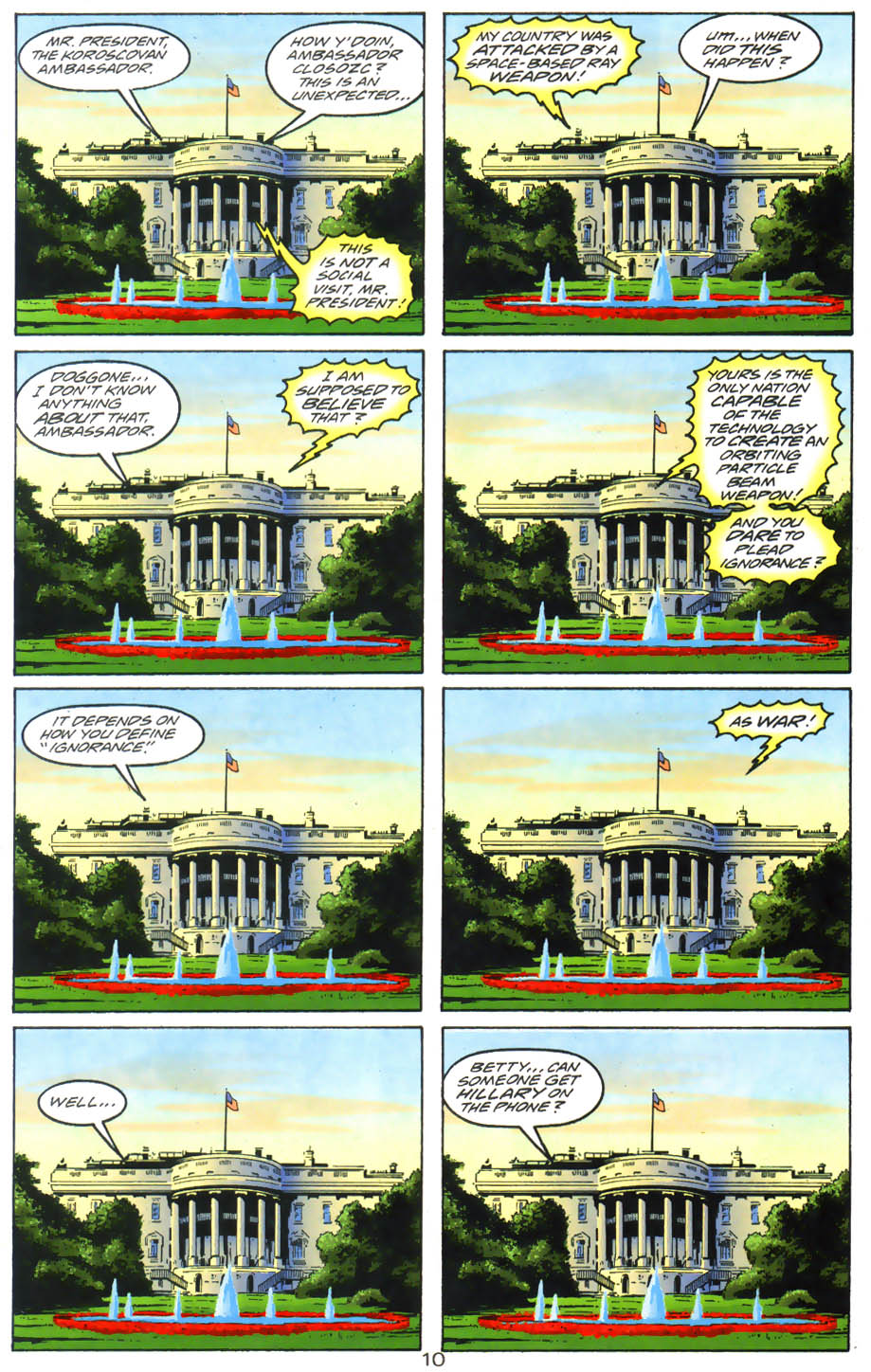

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen #1

The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen #1

That said, you could see Moore gradually stretching the playing field. There were allusions to previous leagues, headed by Prospero and Gulliver. LOEG’s second volume included a super-dense appendix, titled ‘The New Traveller’s Almanac,’ which sought to map out an imaginary geography stringing together all the masterworks of fantastic literature (with the exception of José Saramago’s Baltasar and Blimunda), throwing in some surrealist films as well (Duck Soup, Yellow Submarine… even The Big Lebowski!). Although Moore’s prose is always a treat, I admit the main appeal of this travelogue was figuring out the references (look, it’s Fenwick from The Mouse that Roared and Quiquendone from A Fantasy of Dr. Ox!), as there wasn’t much of a narrative thread (even if Moore did bury a key plot point for later arcs between the lines of the section on Africa). Still, I cannot help but geek out when coming across a page that crams together allusions to Candide, One Hundred Years of Solitude, and Goldfinger!

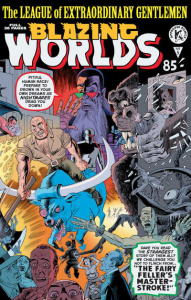

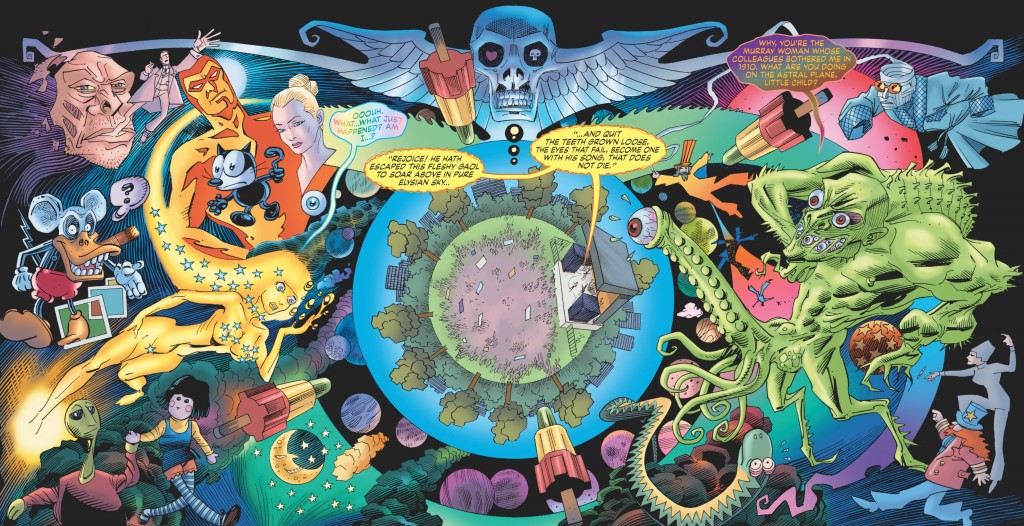

The big turning point in LOEG’s acclaim came with the graphic novel Black Dossier, where the balance between action and parodic pastiche shifted considerably. The driving story found Mina Murray and Allan Quatermain in 1958, after the collapse of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four dictatorship (which was thus recontextualized from the titular future into the early Cold War, syncing that book’s timeline with the era that conceived it), but this turned out to be a mere framing device, as the bulk of Black Dossier was a collection of scattered documents from the League’s secret history. Although there was obvious symbolism in the way the heroes gradually escaped into the realm of imagination (here called ‘The Blazing World,’ after Margaret Cavendish’s utopia), their saga became secondary to a bunch of bizarre literary mash-ups, approaching Lovecraft’s Cthulhu mythos by channeling P.G. Wodehouse’s witty turns of phrase (‘I burst in, in high dudgeon, and prepared to give this idler Peabody a fair piece of my mind, of which I have a good few pieces left to spare, despite what everyone who knows me cares to say upon the topic.’) or Jack Kerouac’s and William S. Burroughs’ beatnik stream of consciousness (‘…alla rest o these primordial yeggs n cosmic dregs n anti matter bums n beggars can seep in yer scooped out skull lay eggs ad jingle caviar control bugs slaver ants is what they are got wiretaps on yer daydreams sex schemes holy blazin visions in their dogditch convict searchlight beams n all yoomanity’ll soon be pressin levers in its ratbox gitting monkeyshocks…’).

Many readers then turned on the series, accusing it of pretentious navel-gazing and of betraying the initial promise of more-or-less conventional fun. (If any of those readers is reading this, stop moaning and go check out Ian Edginton’s own shared comic universe, especially Stickleback and Ampney Crucis Investigates, which draw on the same type of influences without straying as far afield.) Another strain of criticism attacked the comic’s rehabilitation of the children’s character Golliwog, now rightly considered a cringeworthy racial stereotype.

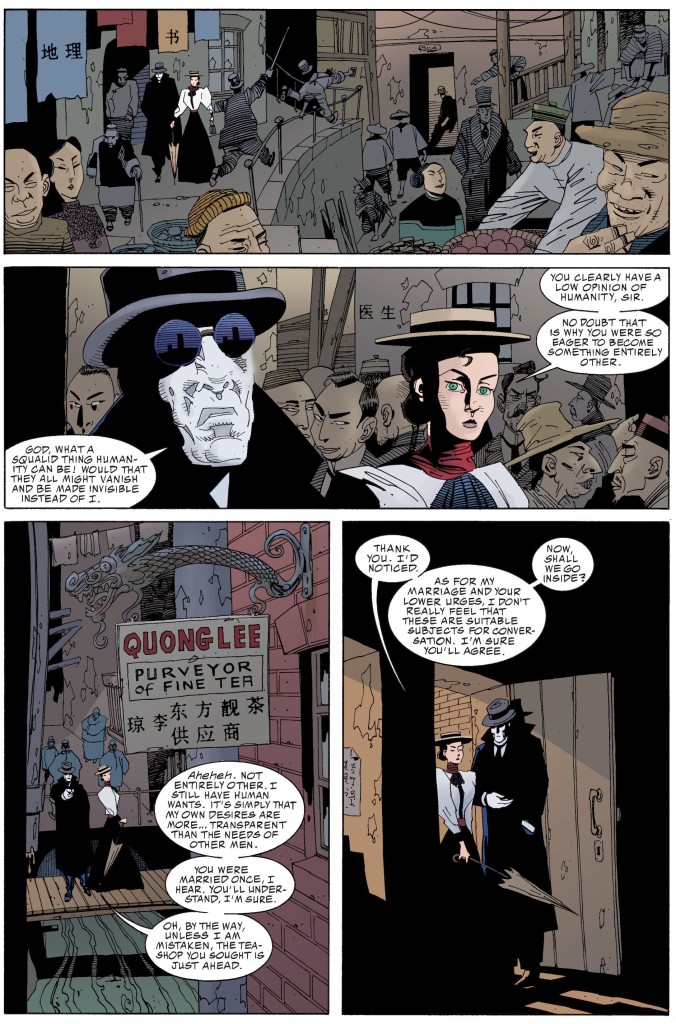

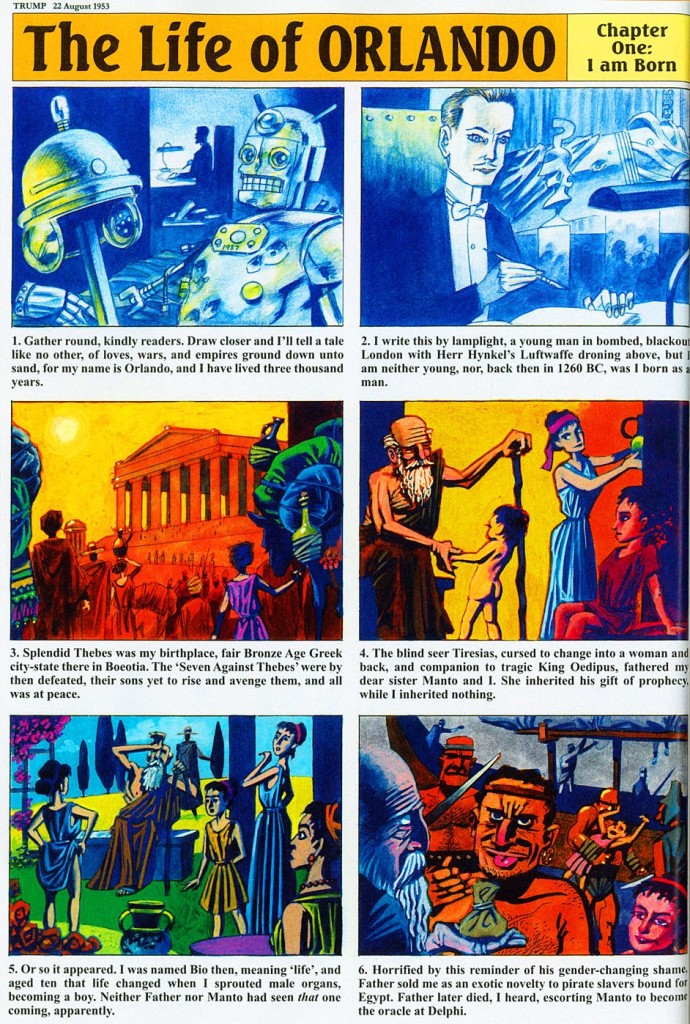

While LOEG may have grown into something that wasn’t exactly what the original fans craved, it also interestingly grew into something that its creators felt truly passionate about. You can sense the care and thought and joy writer and artist put onto each page (which is more than you can say about most long-running comic book series). The same goes for colorist Ben Dimagmaliw and for letterers Bill Oakley and Todd Klein, who got to stretch their muscles through a variety of artefacts, such as a pornographic pamphlet from Nineteen Eighty-Four’s Pornsec (where the characters talk in Newspeak) and a set of postcards sent by Mina and Allan from around the world. And don’t even get me started on the comic-within-a-comic – emulating the historical strips that appeared in 1950s’ British comics – retconning Virginia Woolf’s Orlando: A Biography:

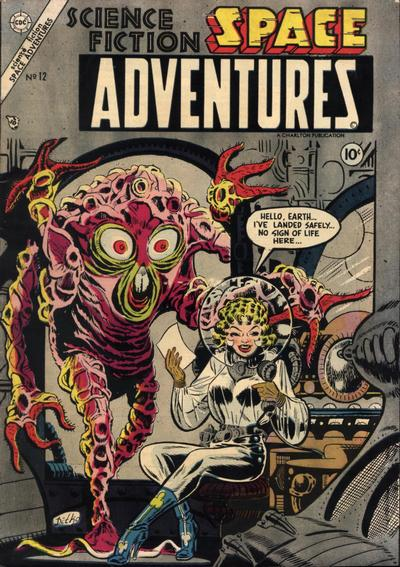

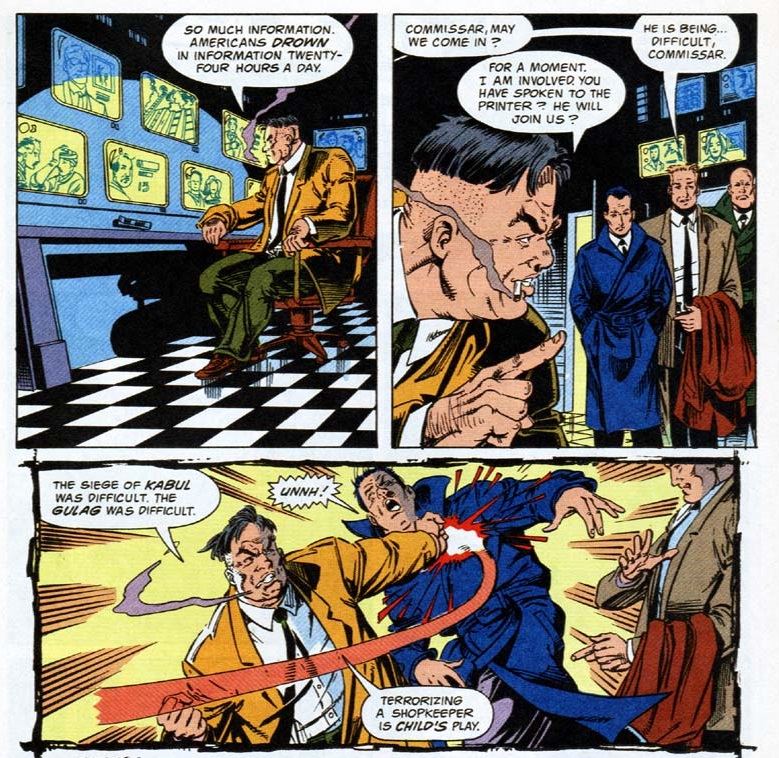

Black Dossier

Black Dossier

Not that the authors were the only ones having a good time: although it’s tempting to accuse LOEG of merely applying to the literary canon the kind of fanboyish continuity OCD that dominates superhero comics, I think that’s missing the point… Yes, this is masturbatory fanfic, but it’s masturbatory fanfic written by Alan Moore, which means that it’s done on an unprecedented, mind-bending scope. You don’t have to recognize every single deity in the theological treaty ‘On the Descent of Gods’ – or to recognize its author as W. Somerset Maugham’s caricature of Aleister Crowley (who goes on to play a large role in the next book) – to be blown away by the way Moore ties together all sorts of mythologies, both historically worshipped (biblical, Greco-Roman) and admittedly fictional (by the likes of Robert E. Howard and Michael Moorcock).

Granted, the meticulous world-building and in-your-face name-dropping can get tiresome in places. Yet I think it’s a gross exaggeration to argue, like some do, that LOEG as a whole became little more than a spot-the-reference game, Family Guy-style, where pleasure derives only from recognition. For one thing, Moore’s wit and O’Neill’s retro, angular visuals often kept things pretty enjoyable on their own terms, even if you don’t feel like checking out Jess Nevins’ comprehensive annotations.

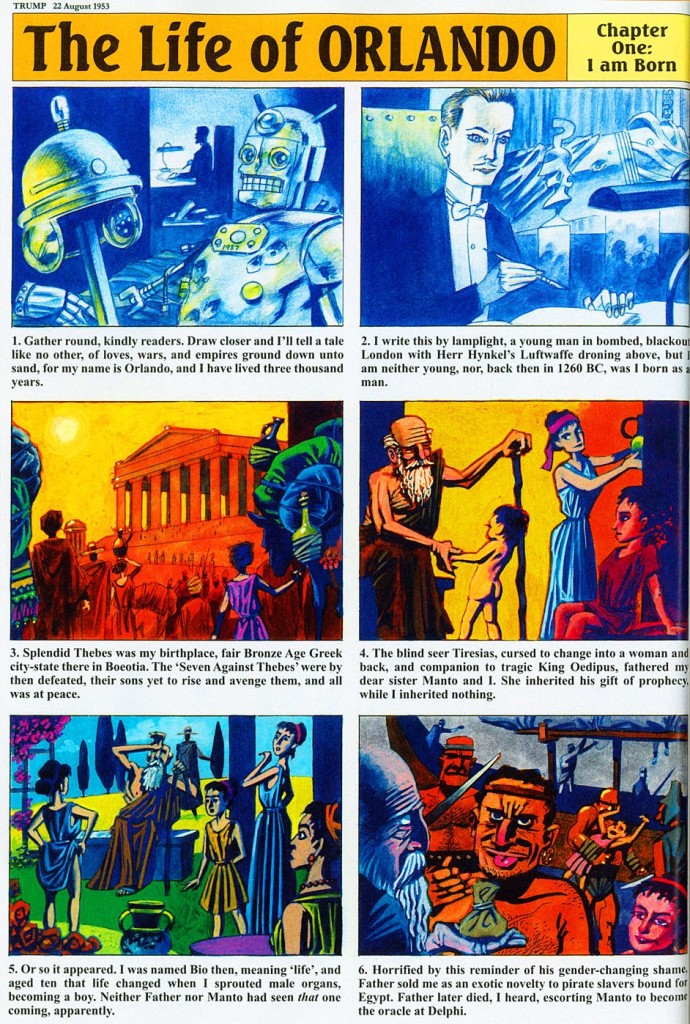

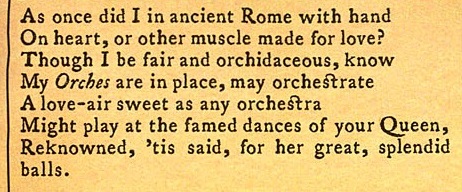

Sure, Black Dossier gets better the more familiar you are with the diverse source material. And sure, not all of it is going to do it for you in the same way, as sometimes you may find yourself admiring the authors’ boldness, intelligence, and craftmanship rather than emotionally succumbing to the final product’s charm. However, the book still works on multiple levels. While part of the appeal of the Shakespearean play ‘Faerie’s Fortunes Founded’ is contemplating Moore’s skill at mimicking the Bard’s iambic pentameter, we get more than an SNL-like empty impersonation: on the one hand, Queen Gloriana’s words foreshadow later developments and reveal an in-story reason for the League’s creation (to knit the realms of humans and gods) which doubles as a thematic statement; on the other hand, the wordplay is itself quite amusing, like when Orlando explains that he is (currently) a man while repeatedly alluding to testicles in his word choices:

Black Dossier

Black Dossier

(We later see a performance of this play in the Blazing World, in LOEG: The Tempest.)

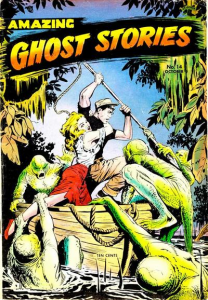

Plus, the riffs and references aren’t just self-indulgent winks… From the outset, LOEG’s clever merging of narratives served to comment on the obsessions and violence of the culture that spawned them in the first place, so that underneath the superficial thrills there was always plenty of rich subtext to explore, not to mention several layers of moral complexity. Moreover, as argued by Jeff Thoss, there is a poignant historiographical gesture in the series’ resurrection of comics’ affinities with paraliterary traditions going back to the nineteenth century, as it invites readers to envision a new genealogy of the comic book medium itself.

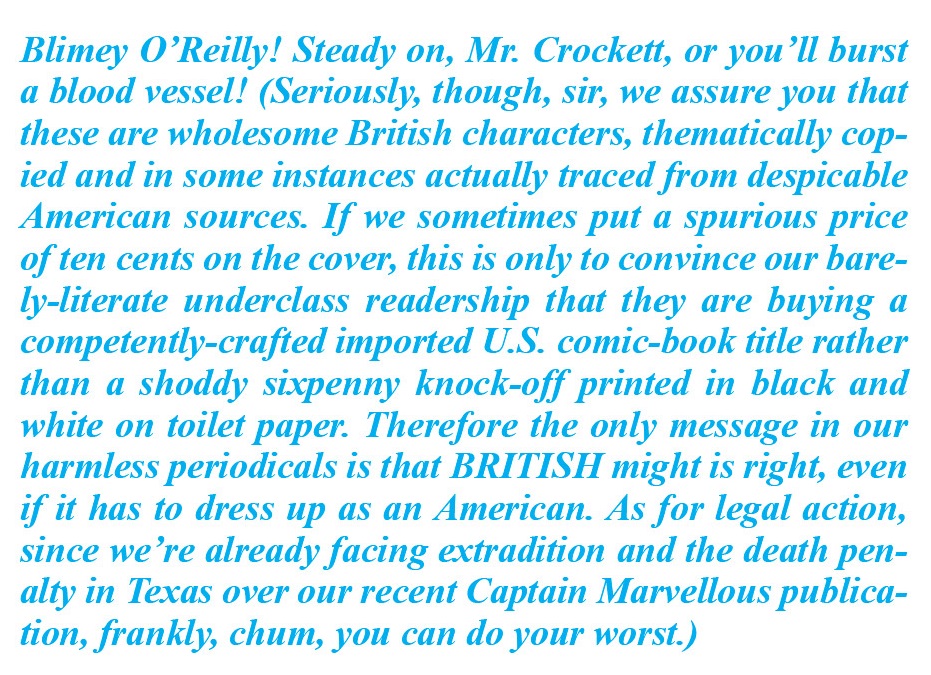

Notably, Moore kept revisiting his pet concerns, including posthuman transcendence and the power of ideas. His work has often dealt with the connection between these two themes, not only through drugs (also addressed in LOEG), but through the escapist, emancipatory potential of imagination. Going radically beyond a mere poststructuralist acknowledgment that language frames perception, Moore has made an illustrious career out of ‘mind over matter’ imagery. It’s not just Gloriana who speaks of bridging reality and myth – in Black Dossier’s psychedelic closing sequence (in 3-D!), Prospero further underlines that one of the book’s major themes is the impact of fiction itself. In one of those beautiful monologues Moore can do so well, a fourth-wall-breaking Prospero (whose long beard gives him a Moore-ish look) points out that, just as humanity created stories (like the ones in LOEG), it was also shaped by them, drawing inspiration from their ideals. ‘On dream’s foundation matter’s mudyards rest. Two sketching hands, each one the other draws: the fantasies thou’ve fashioned fashion thee.’

(Between his baroque prose and naughty playfulness, Alan Moore’s style has always reminded me of Umberto Eco, who also explored the whole fiction-shapes-reality motif, particularly in the brilliant Baudolino. Although less caustic, Jorge Luis Borges and Italo Calvino come to mind as well, so I was not surprised to find plenty of allusions to these authors’ writings in ‘The New Traveller’s Almanac.’)

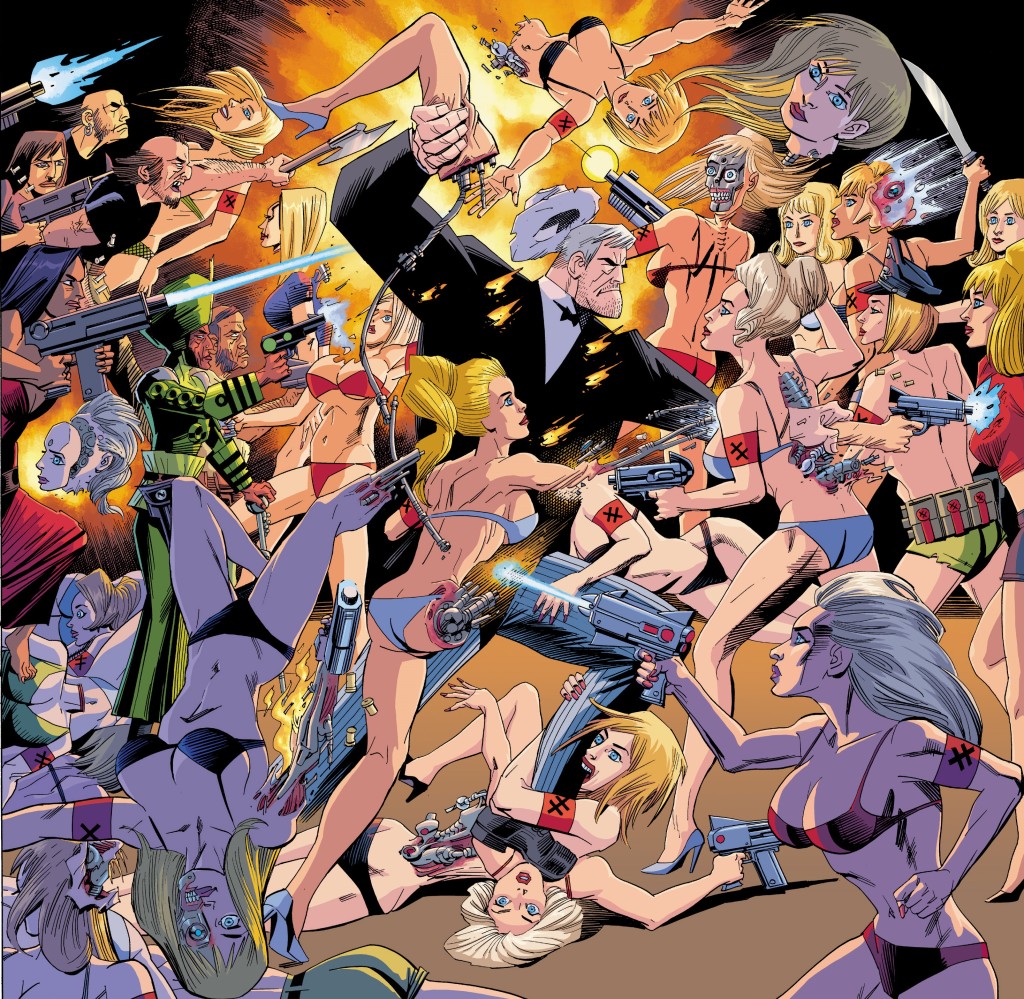

In the next post, I’ll discuss how Moore and the rest of the gang continued to expand this project through a set of books that approached the fictional history of the twentieth century by somehow amping up LOEG’s level of nastiness and debauchery. If you thought Black Dossier didn’t go easy on readers, wait until you see what comes next…

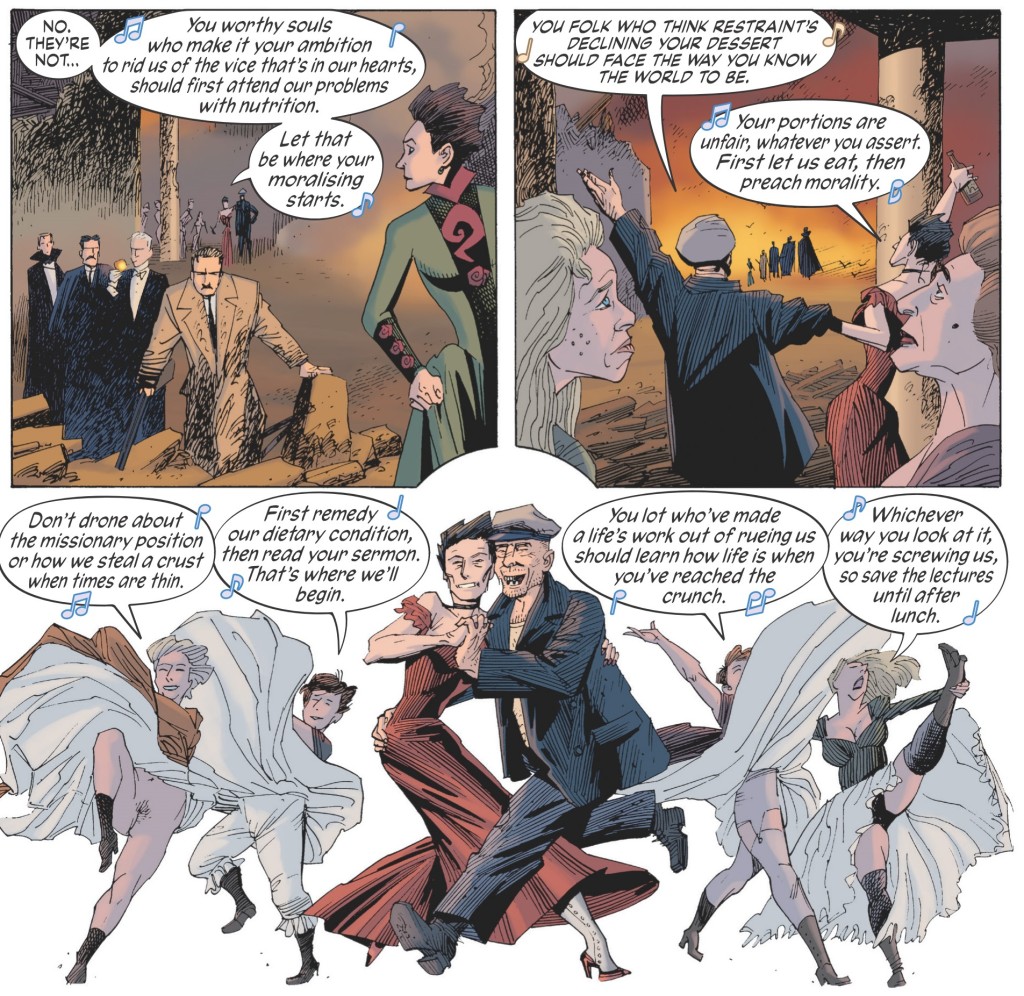

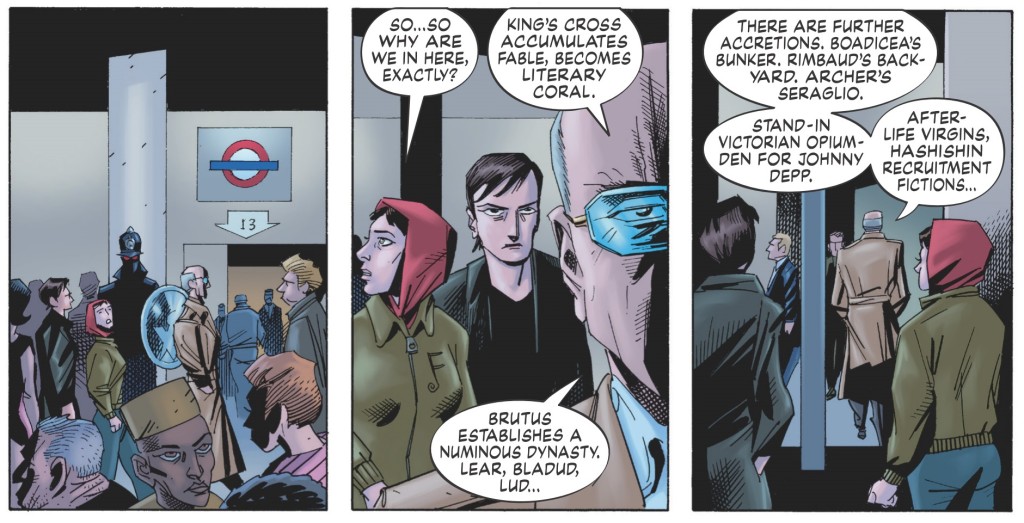

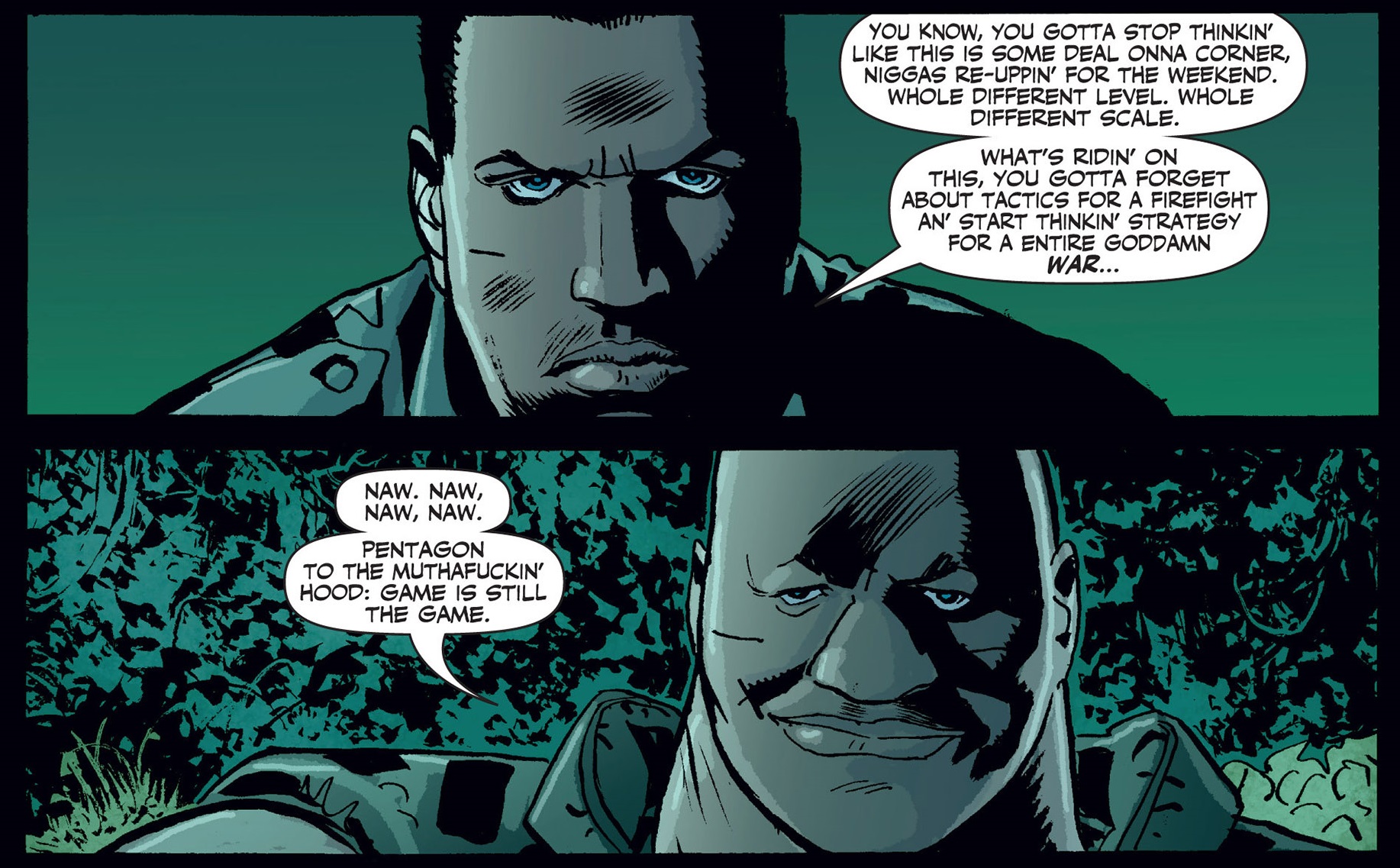

Century: 1910

Century: 1910