Writing about Todd Phillips’ Joker last week got me thinking about the fact that, by now, taking superhero iconography and filming it like a horror movie has become a proper subgenre onto itself. I’m not just talking about the occasional Lovecraft-influenced sequence in Aquaman or Doctor Strange, but about movies in which horror is clearly the main sensibility.

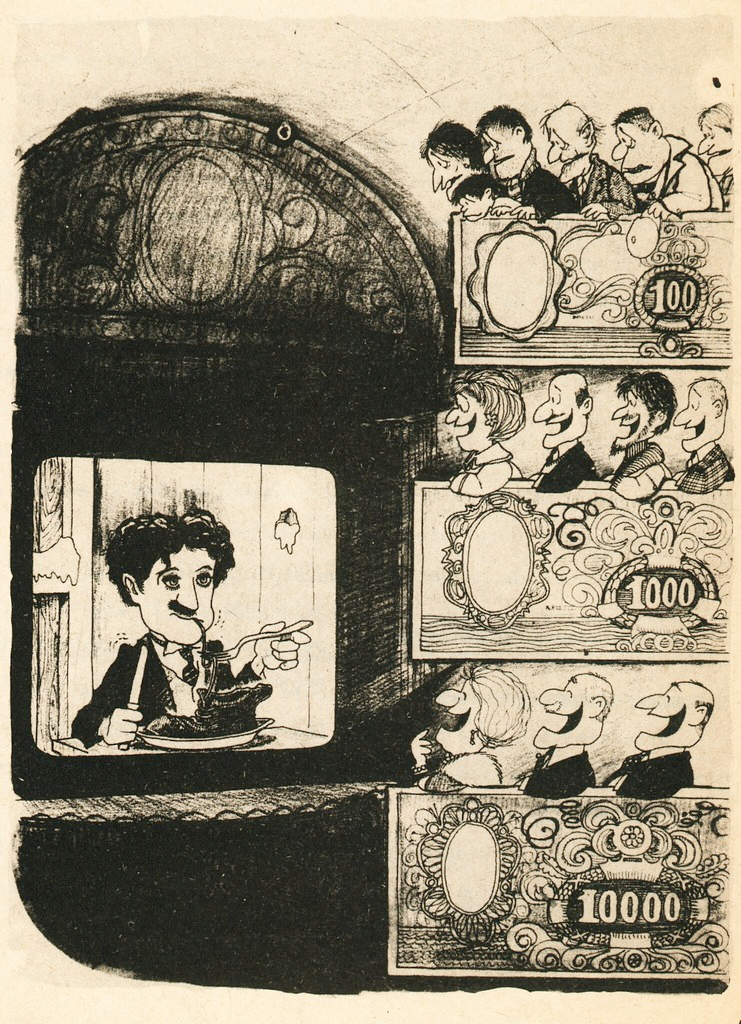

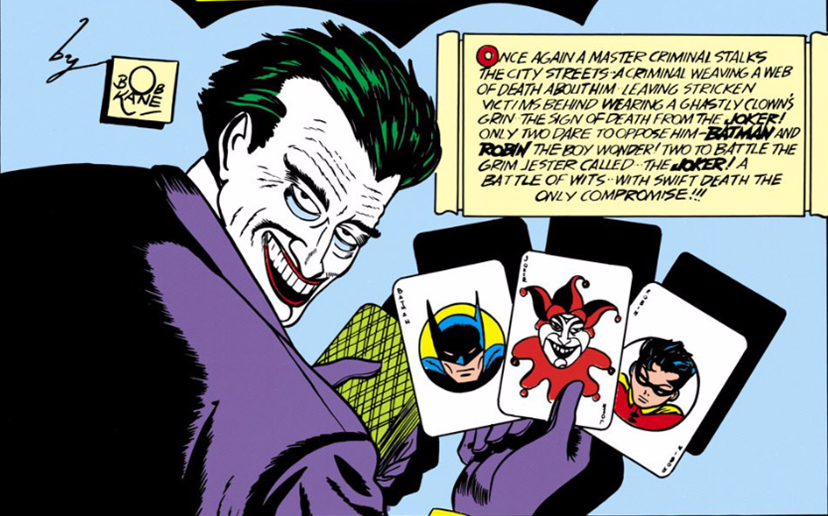

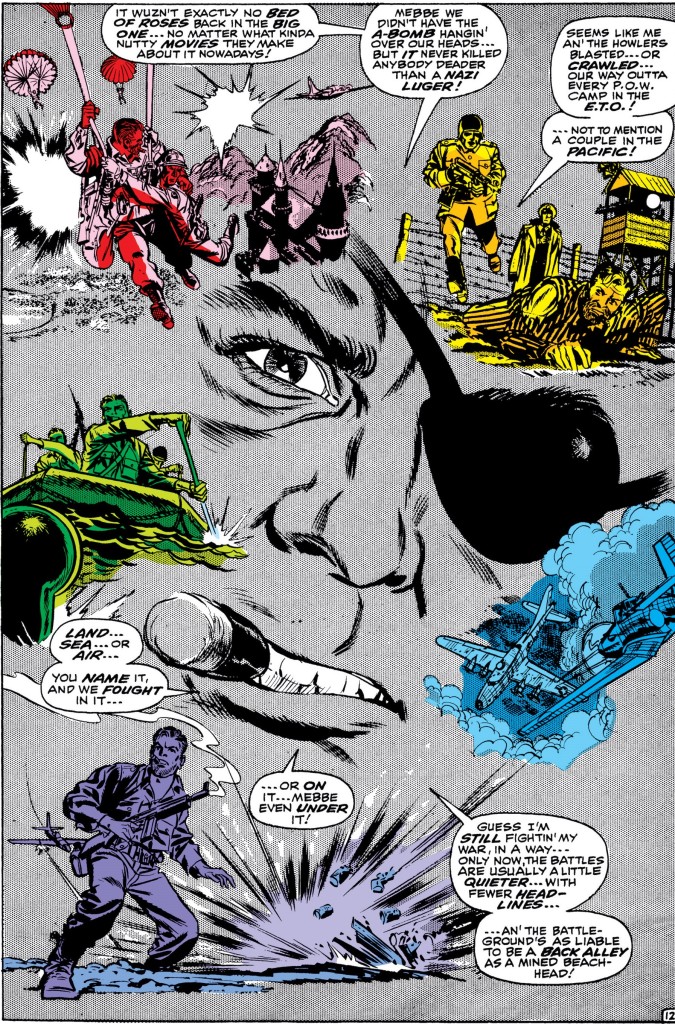

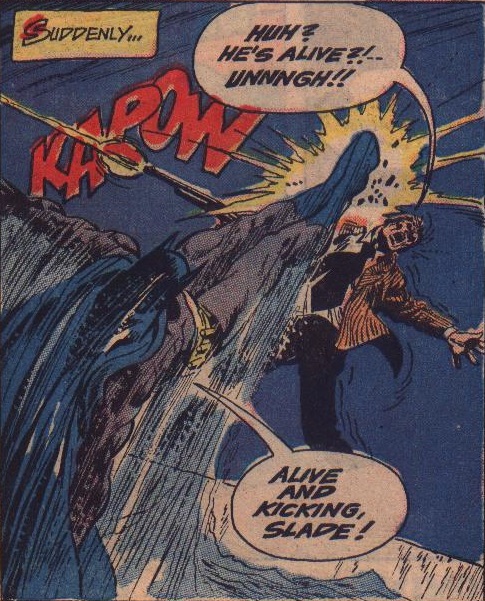

I guess it all goes back to 1989’s super-successful Batman, which Tim Burton shot like the creepy nightmare of a traumatized child from the forties, starting with Jack Nicholson’s own memorable take on the Joker…

Batman (1989)

Batman (1989)

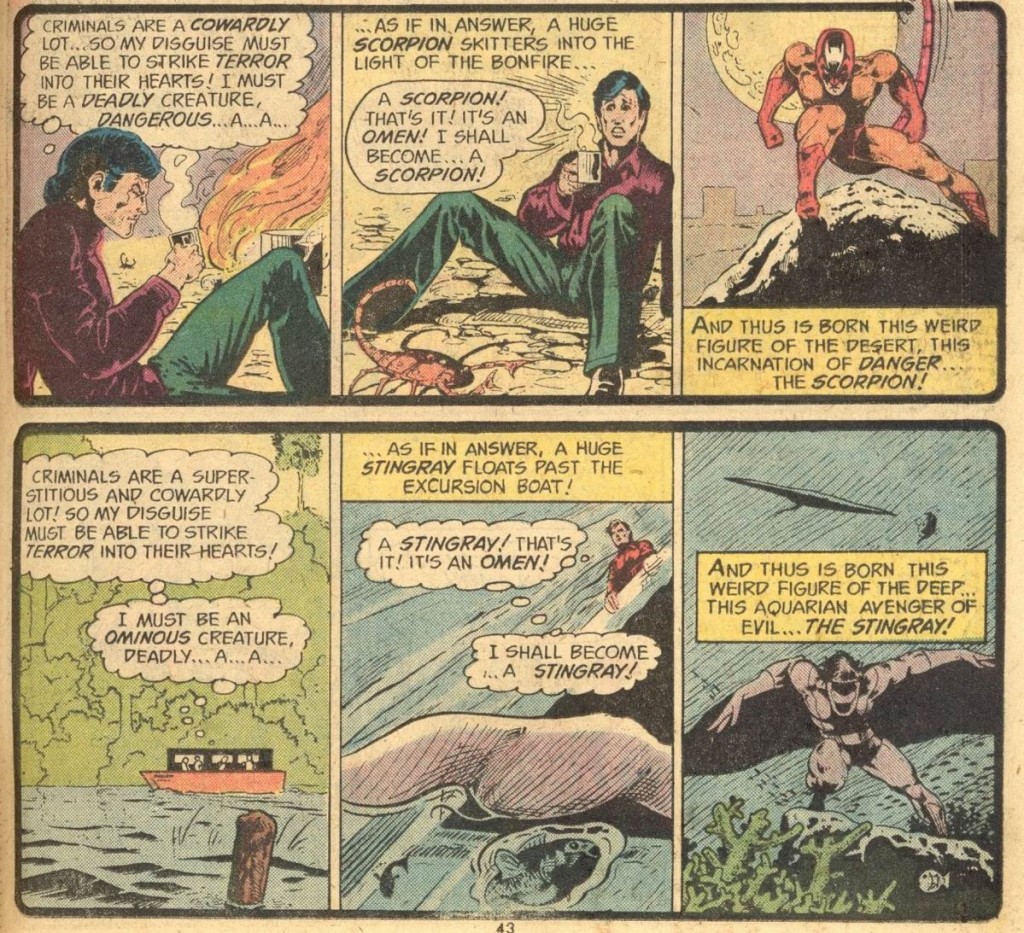

Burton was clearly on to something here, recognizing the sinister potential of bringing comic book characters to life. Both genres lend themselves to easy allegories, which can lead to interesting hybrids: if superhero fiction is about ideals and aspirations, horror is a vehicle to tackle anxieties and fears, so there is something enthrallingly disturbing about combining the two.

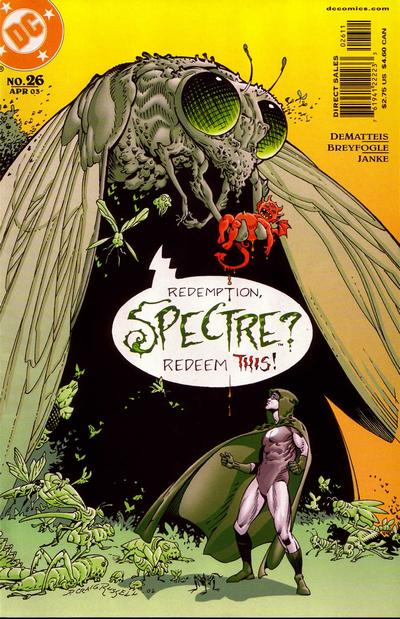

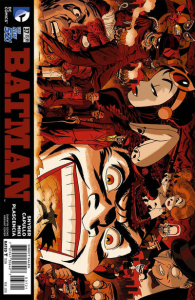

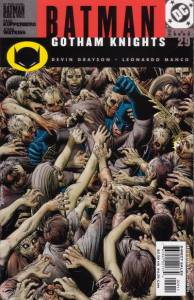

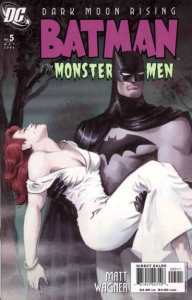

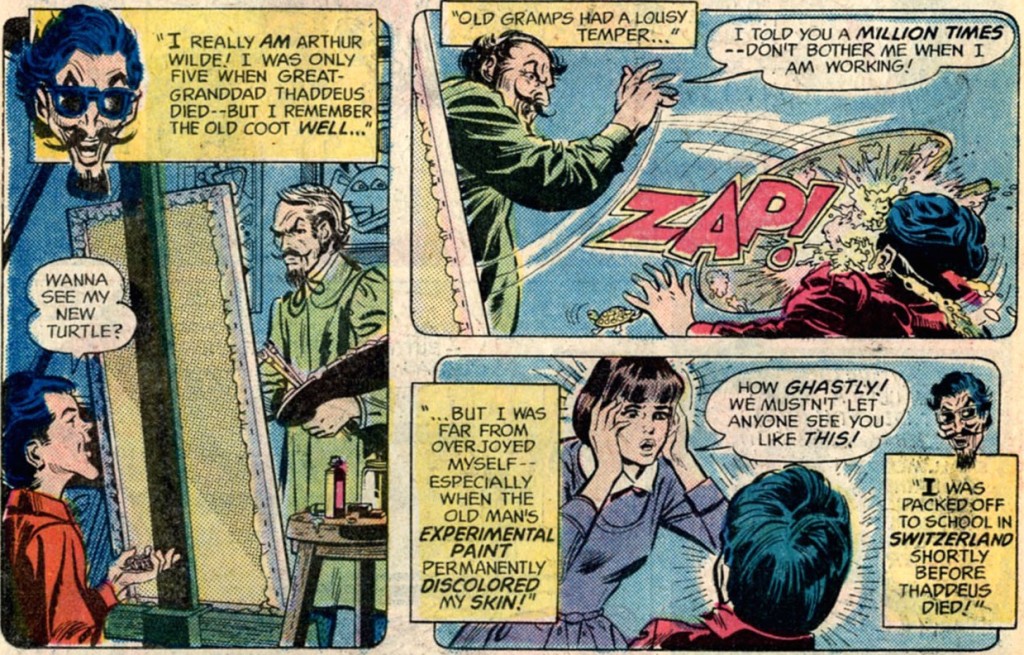

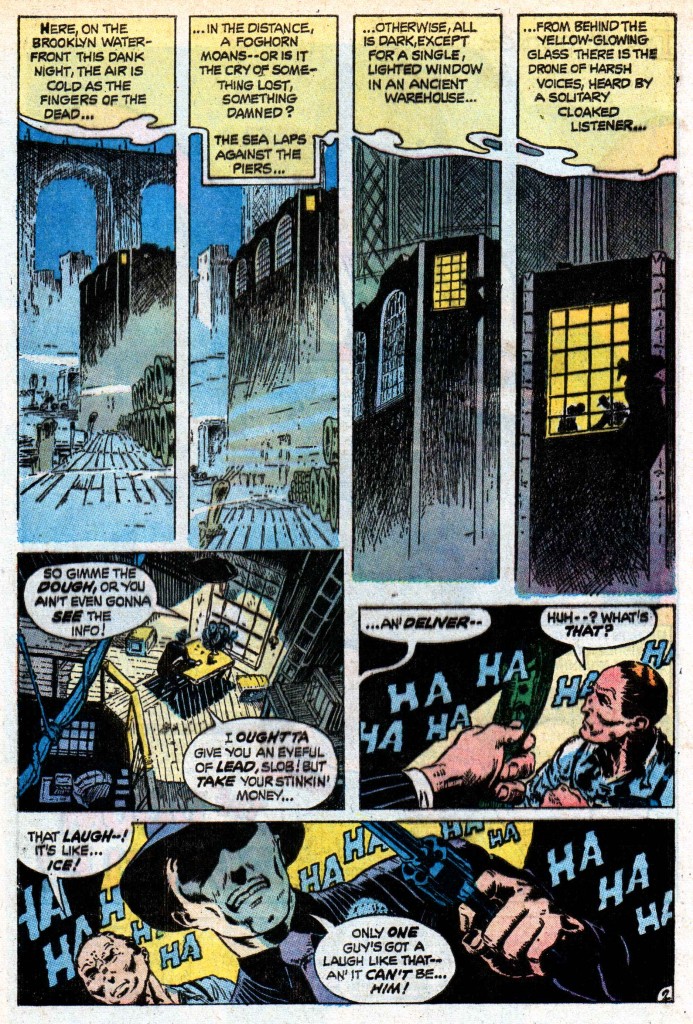

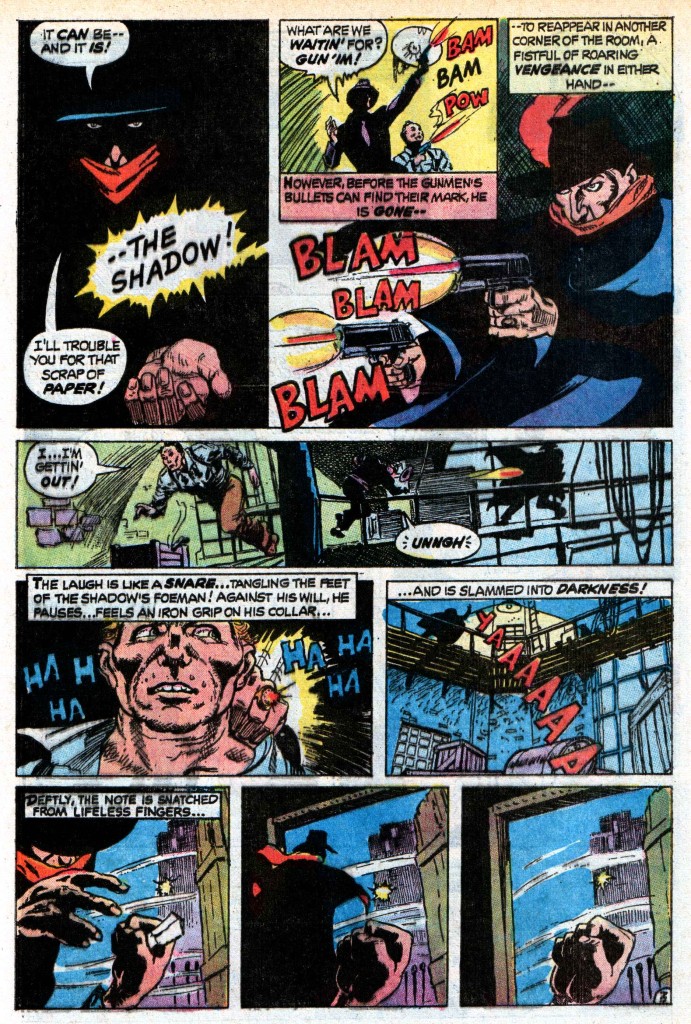

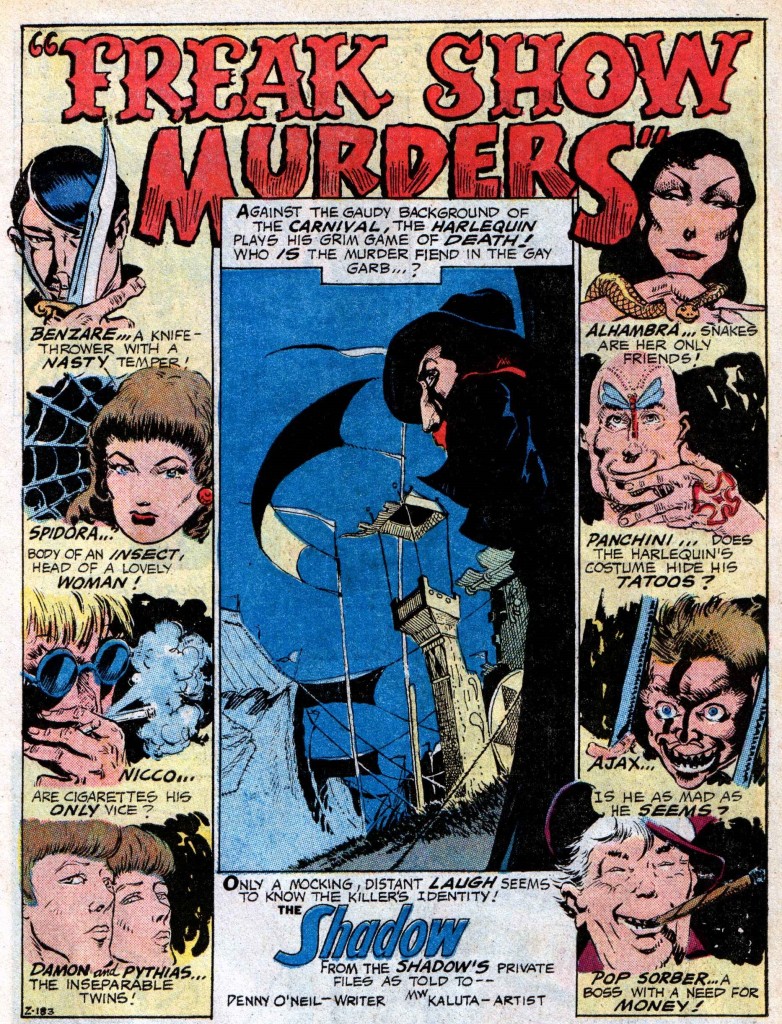

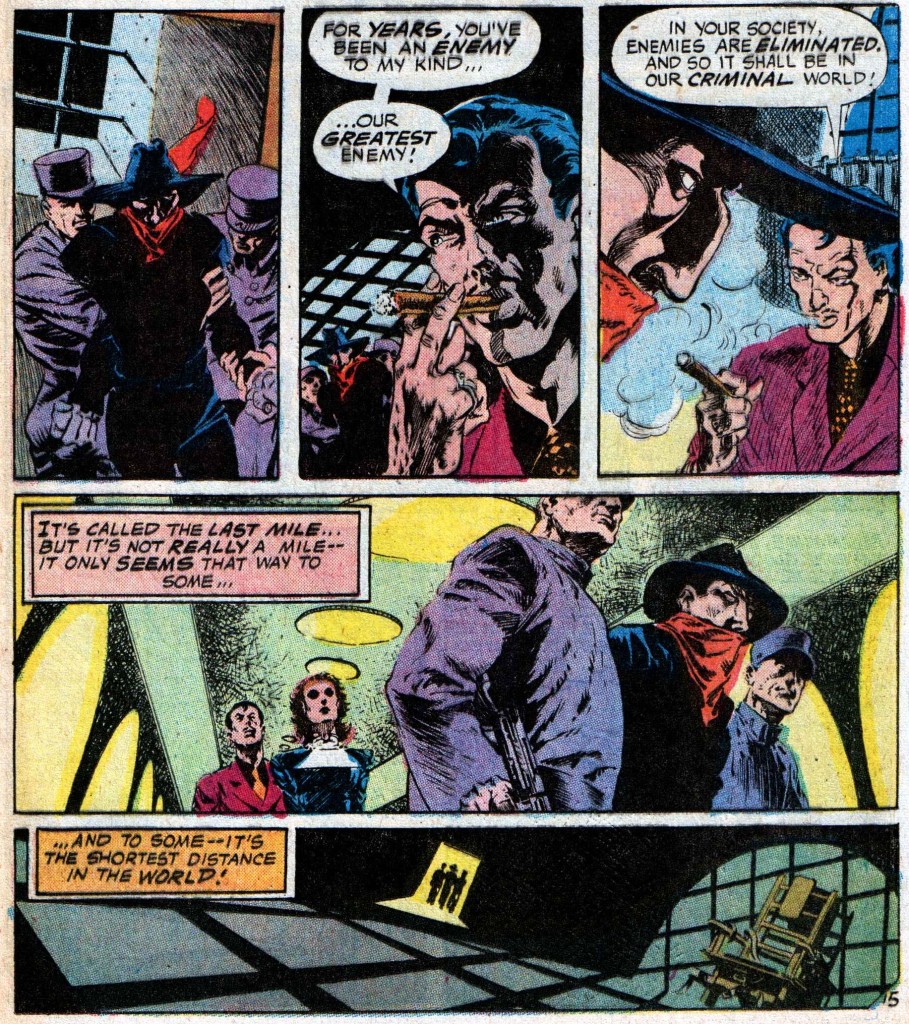

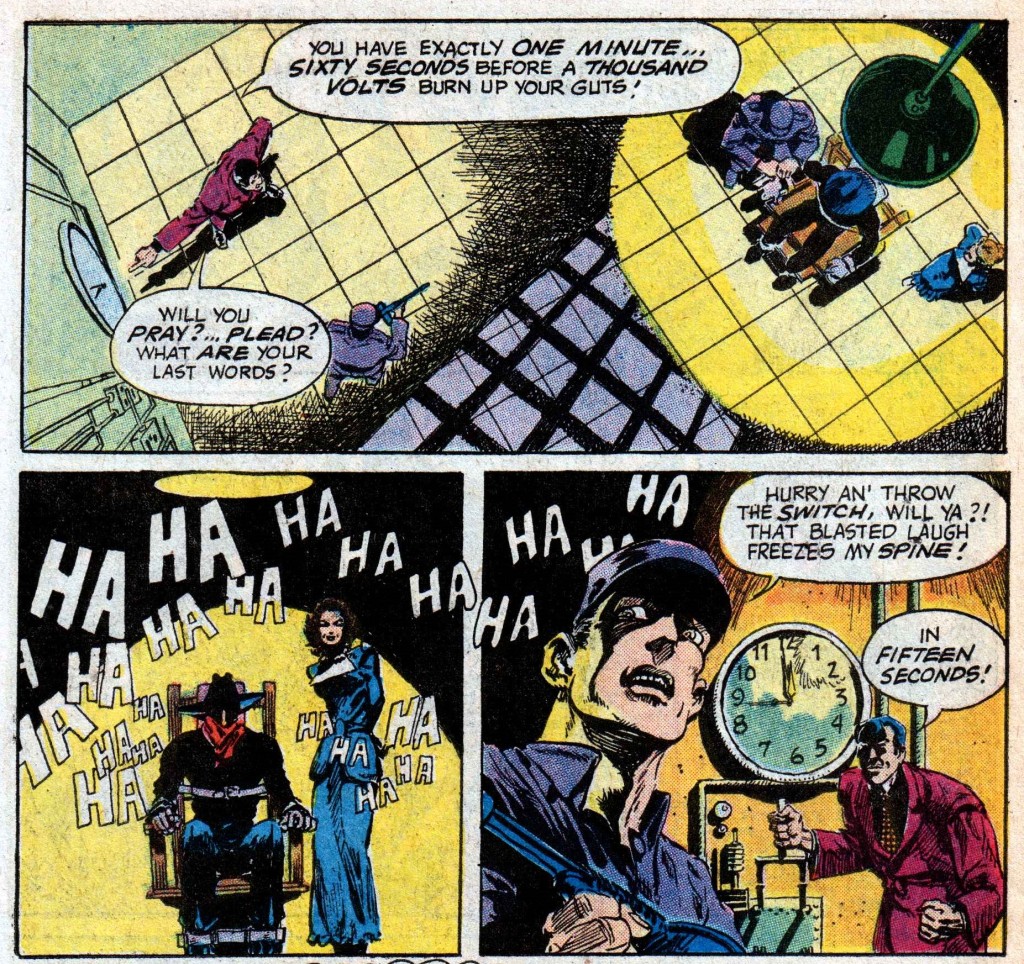

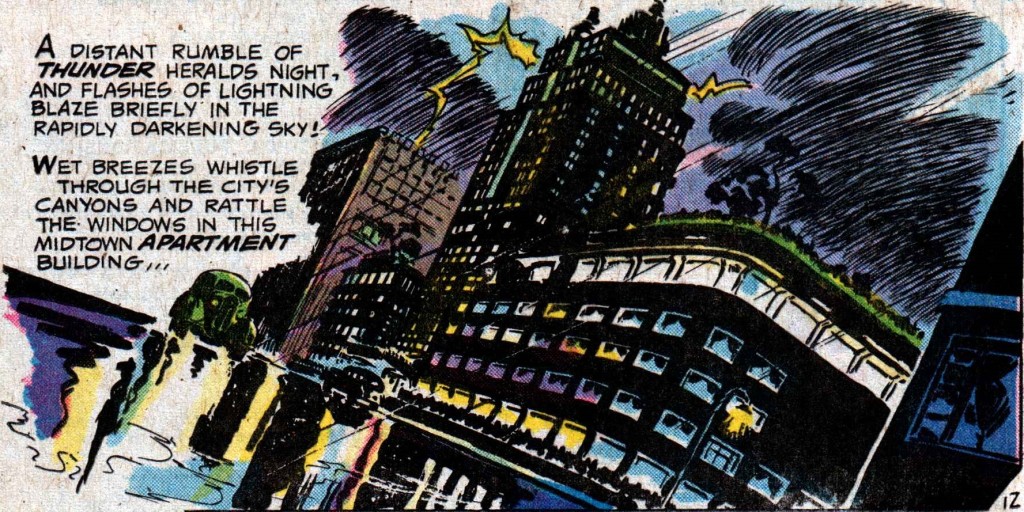

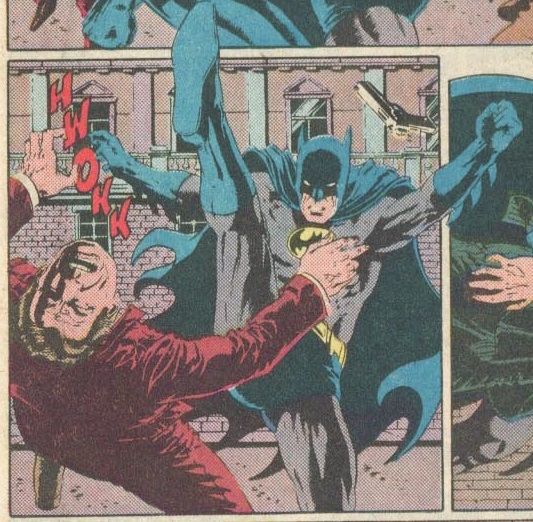

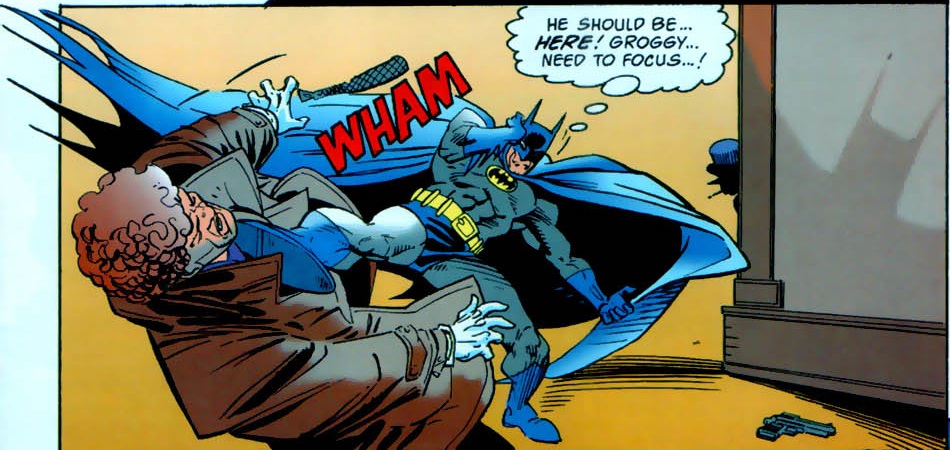

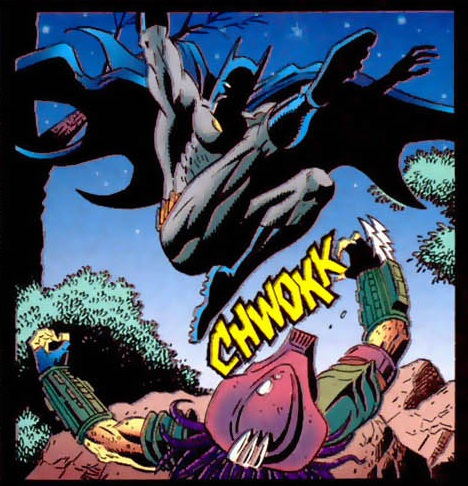

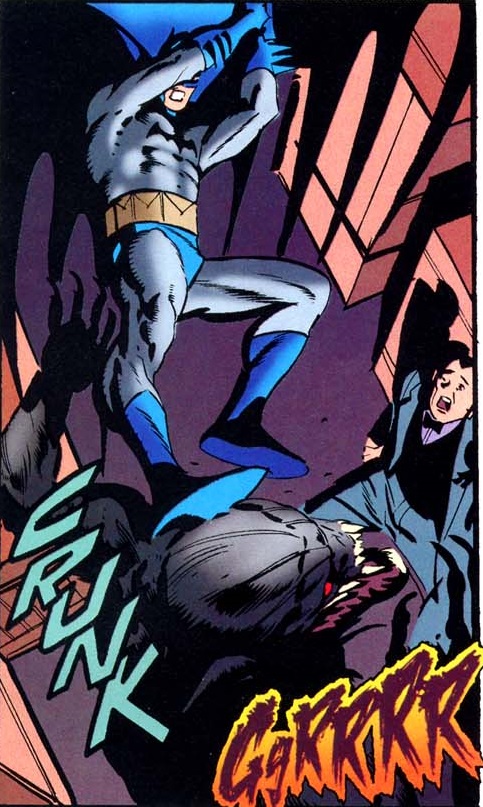

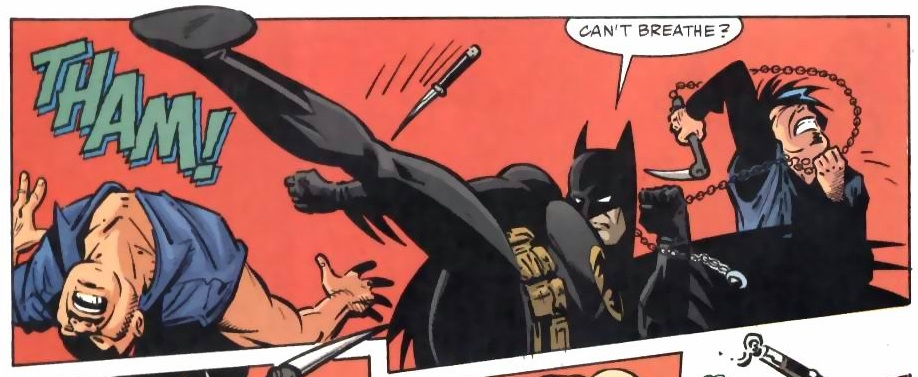

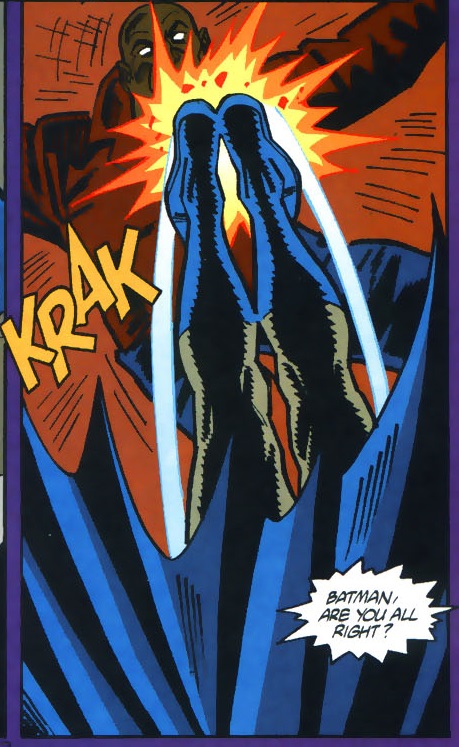

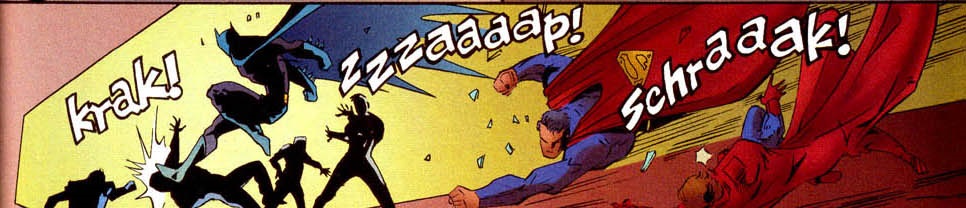

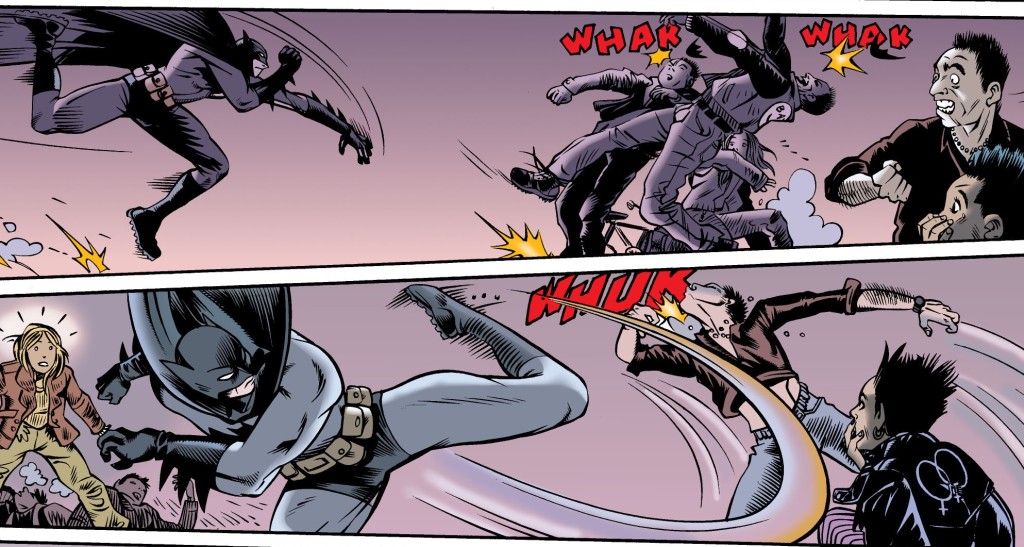

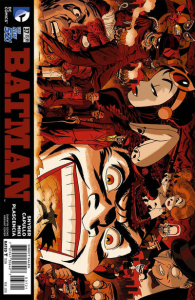

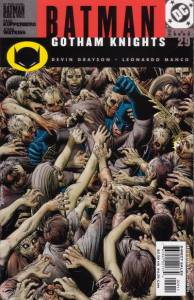

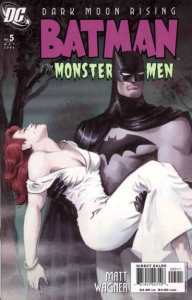

Moreover, although Burton’s film departed from the source material in several key ways, this specific link wasn’t all that strange… From the very start, Batman comics had been full of vampires, mad scientists, and monsters, drawing on the aesthetics of horror movie posters and pulp covers. This has remained an enduring dimension of the franchise:

(Damn it, I forgot to include that last cover on my post about lying in Batman’s arms…)

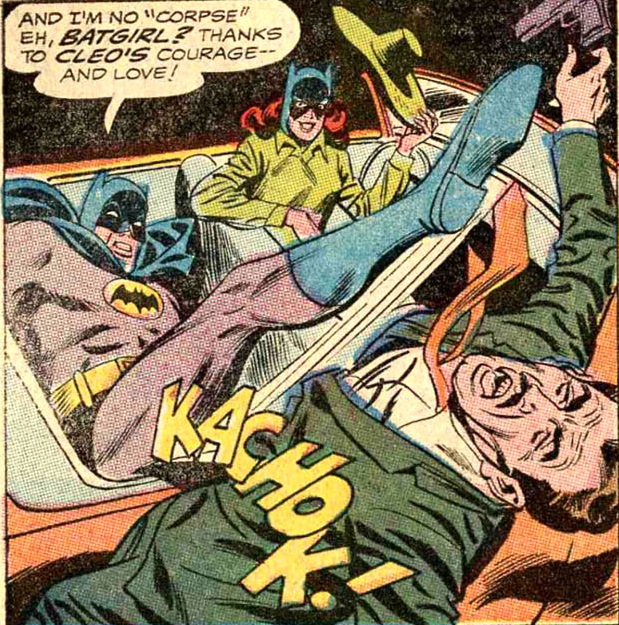

Tim Burton went on to expand his idiosyncratic vision of the Dark Knight’s world through 1992’s Batman Returns, which also borrowed heavily from classic horror cinema (Christopher Walken’s character was actually called Max Schreck). That said, the sequel came across as (even) more of a macabre farce. Seriously, that film’s grotesque Penguin and twisted zombie Catwoman wouldn’t have looked out of place in the following year’s Addams Family Values…

Batman Returns (1992)

Batman Returns (1992)

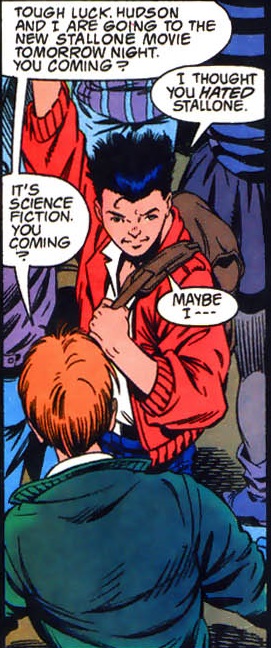

To be fair, much of Batman Returns’ bizarre sense of humor is probably due to the involvement of screenwriter Daniel Waters, who also wrote the cult black comedy Heathers, not to mention the outrageously cartoonish action movies Hudson Hawk and Demolition Man…

The latter one even got a shout-out in the comics, at the time of release:

Robin (v4) #1

Robin (v4) #1

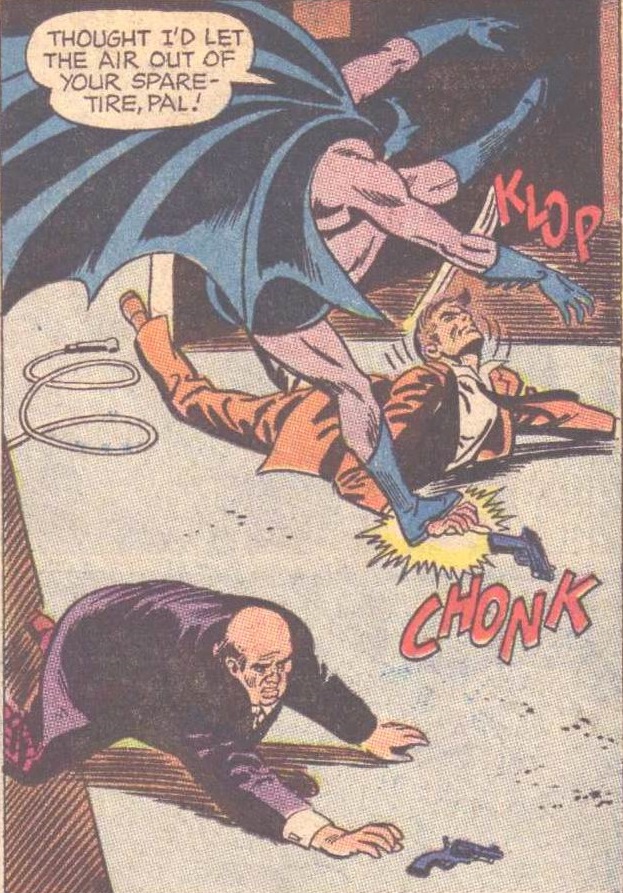

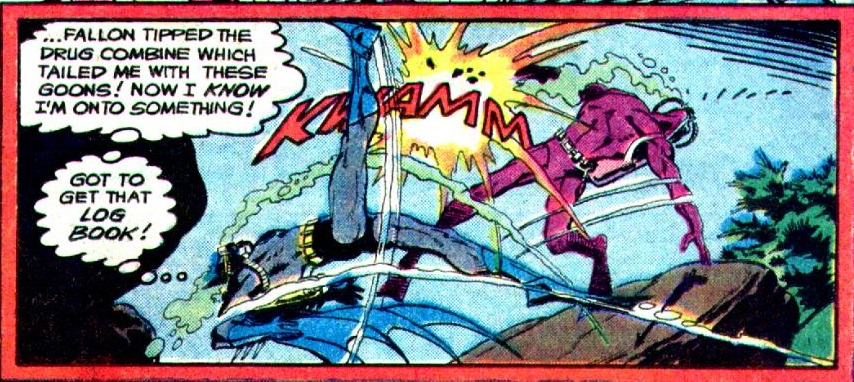

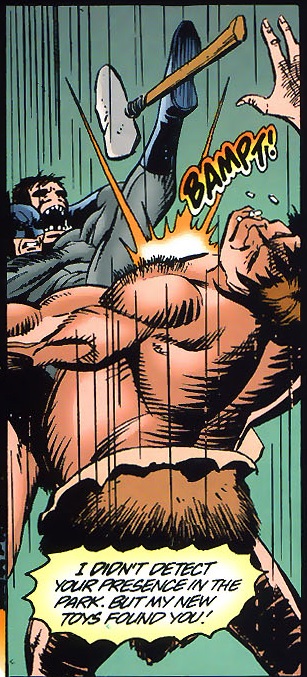

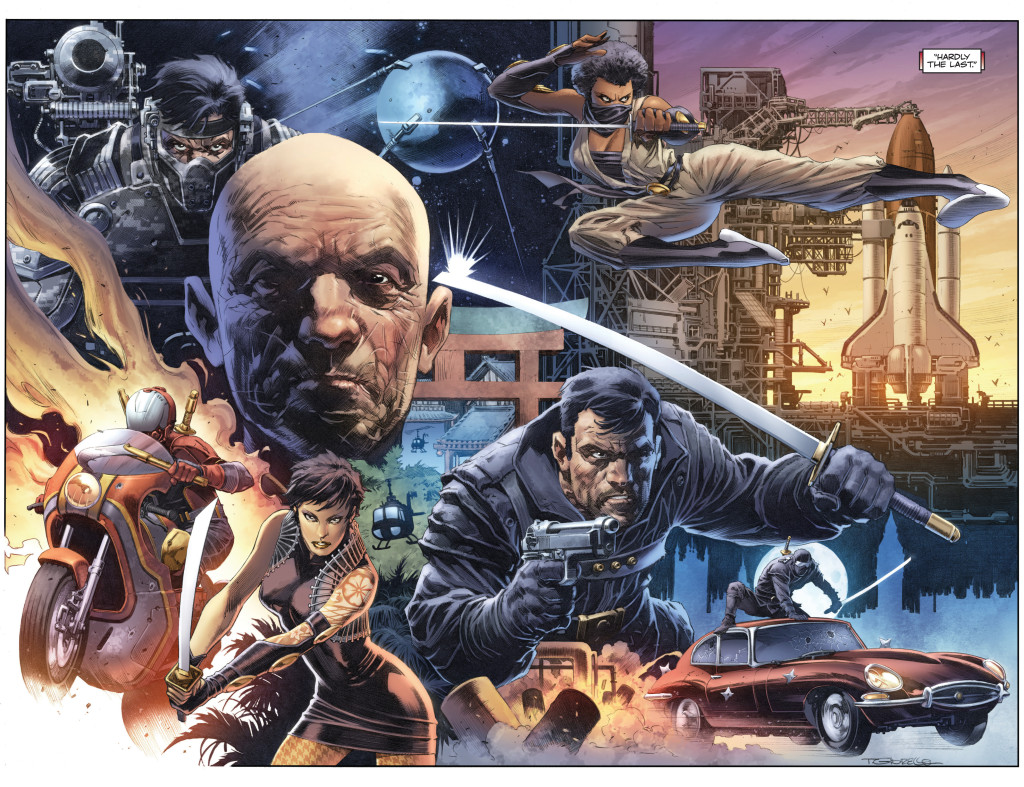

Between Tim Burton’s two Batman pictures, Sam Raimi did his own Danny Elfman-scored, violent blend of dark superhero opera, R-rated action movie, and cornball tribute to old Universal monster films (with a few echoes of RoboCop as well). In 1990’s Darkman, Liam Neeson plays a disfigured scientist on a revenge quest against the gangsters who brutally attacked him and destroyed his lab. When he’s not brooding or shouting in agony, he is setting up zany traps for his opponents, playing them against each other by temporarily assuming their identities (he has developed a malleable synthetic skin that lasts for 99 minutes in the light!).

Darkman (1990)

Darkman (1990)

Darkman’s tone is gritty and often over-the-top, from the finger-chopping mobster to montages of explosions superimposed on close-ups of Neeson’s eyes. The gothic flair is particularly prominent in a subplot about the anti-hero’s girlfriend, played by Frances McDormand. This could almost be the origin tale of one of the Caped Crusader’s many tragic villains… In fact, the grim, sadistic edge is quite in tune with the overall zeitgeist of post-Dark Knight Returns comics at the time (although the climax would’ve felt more subversive if Burton hadn’t played a similar card in the previous year’s blockbuster).

In Sam Raimi’s oeuvre, this stands halfway between the gory comedy of the Evil Dead series and the more conventional superhero shenanigans of his Spider-Man trilogy – not as cartoony as the former, yet much, much more deranged than the latter!

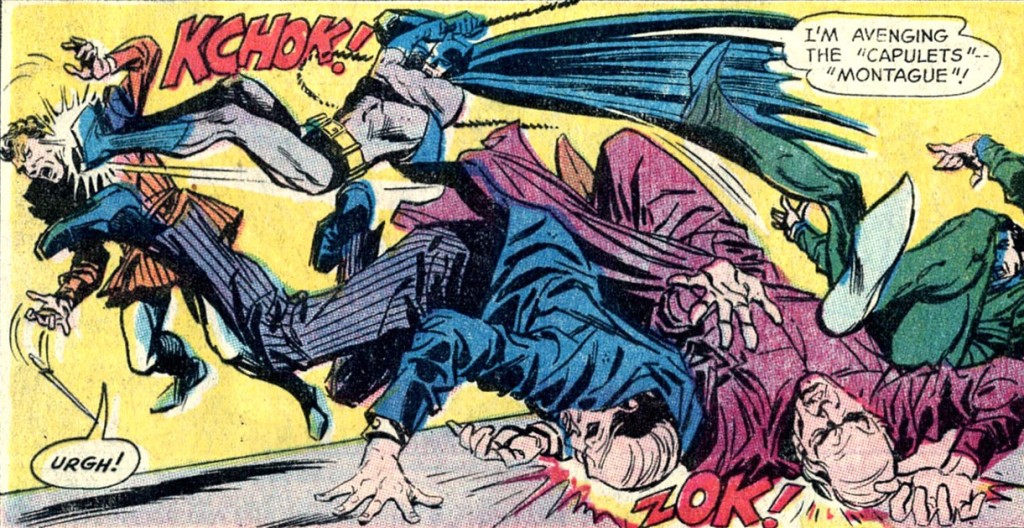

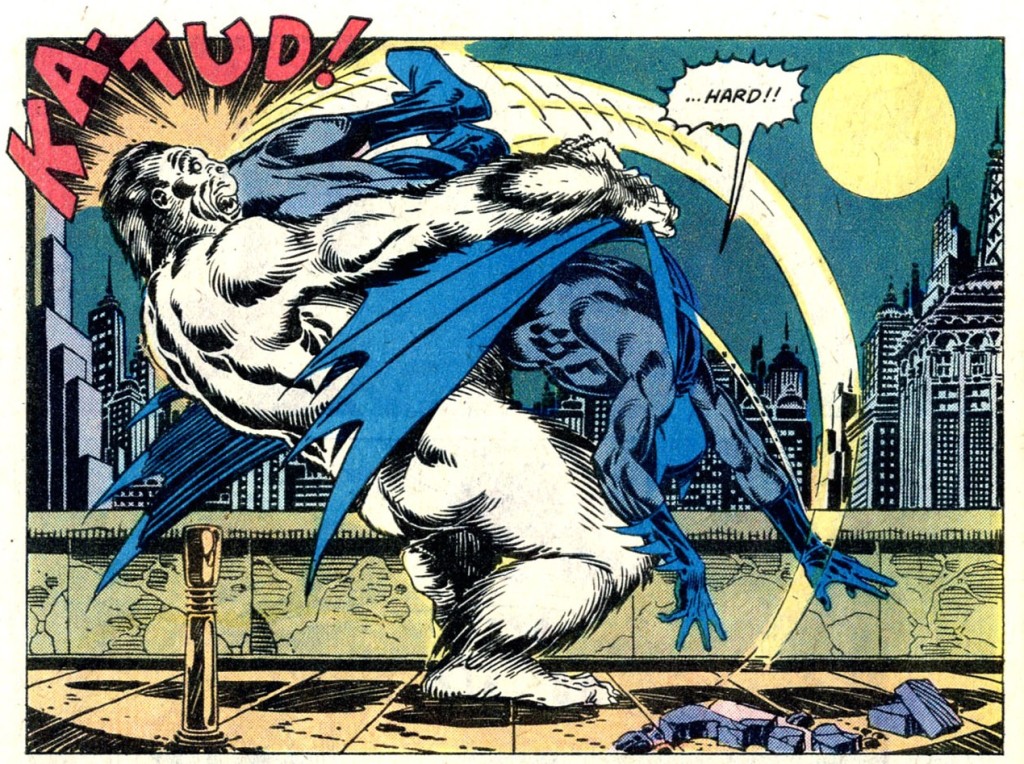

This initial cycle of surrealist gothic superhero flicks culminated in 1994’s The Crow, Alex Proya’s trippy adaptation of James O’Barr’s comic book about a guitarist who comes back from the dead to avenge his raped and murdered bride. I’m not a fan: the whole thing feels too much like an extended emocore music video. Unlike the comic’s version, at least the film’s protagonist doesn’t deal with his emotional pain by engaging in self-mutilation, but you can still count on plenty of poseur moves and pretentious, proto-poetic lines.

The Crow (1994)

The Crow (1994)

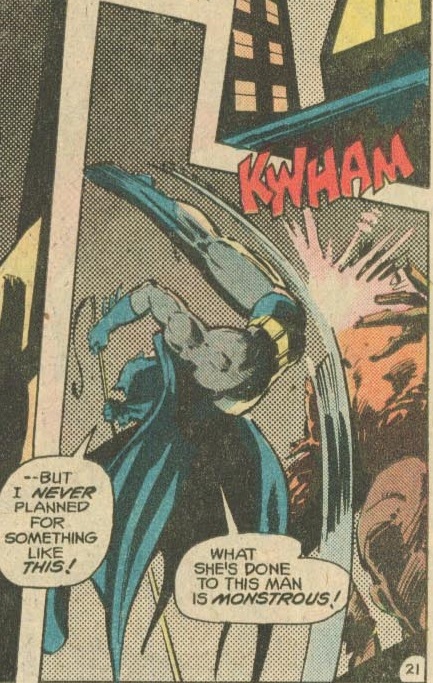

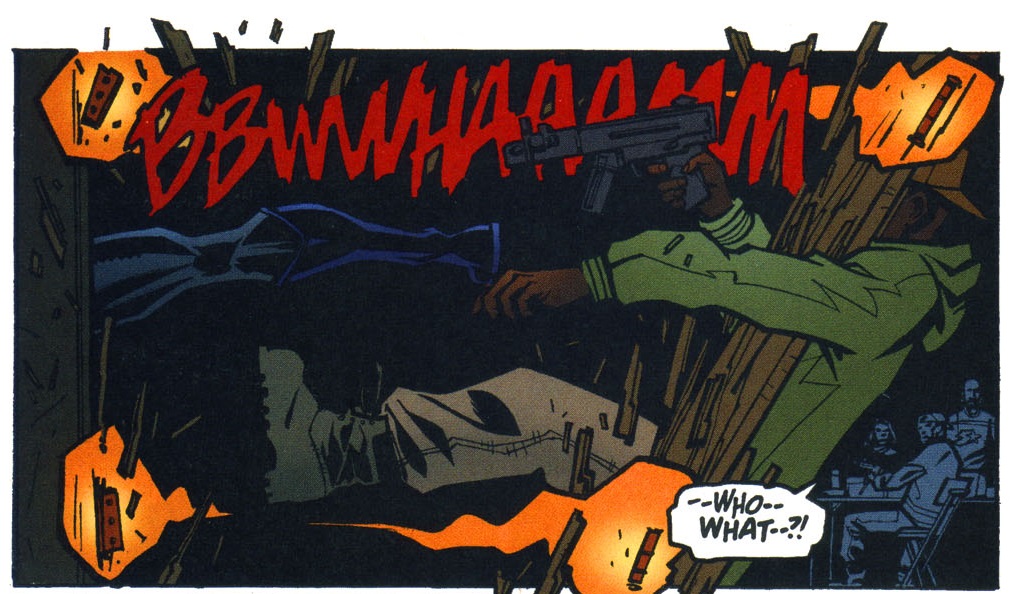

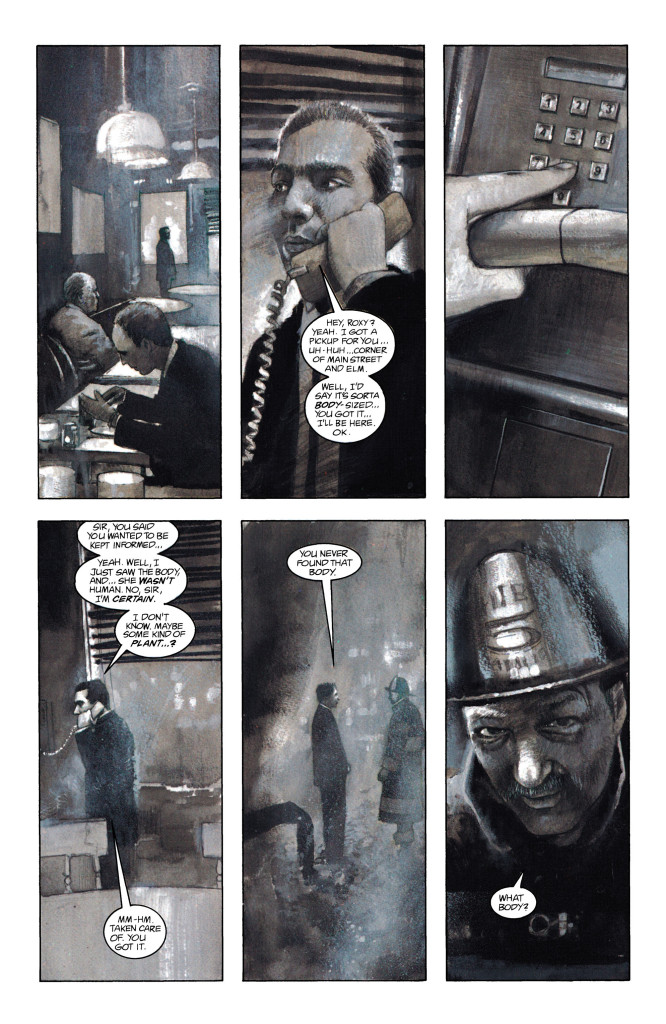

Like its predecessors, The Crow was packed with overwrought pathos and pyrotechnic travelling shots, yet it also imbued the genre with an edgier attitude of nineties’ leather jackets, gun fu action, and harsh profanity. With the possible exception of 1997’s Spawn (which I haven’t seen), the one film that picked up on this new approach – and ran with it in a much more entertaining way – was 1998’s Blade, stylishly directed by Stephen Norrington and starring Wesley Snipes as the titular vampire hunter. This sleazy, adrenaline-charged thriller is like a time capsule of the late ‘90s understanding of coolness: there are techno beats, decadent orgies, bloody violence, mixed martial arts, swordfights, embarrassing CGI, and a firm belief in sunglasses.

Blatantly inspired by Hong Kong cinema, borrowing elements from the Punisher, and clearly anticipating the following year’s The Matrix, Blade is a visual treat, especially the delirious set design (which at one point includes a penthouse with a retractable wall and a waterfall with floating rubber duckies). Above all, Snipes totally owns the part, somehow landing even the weirdest one-liners, like the infamous: ‘some motherfuckers are always tryin’ to ice skate uphill.’

Blade (1998)

Blade (1998)

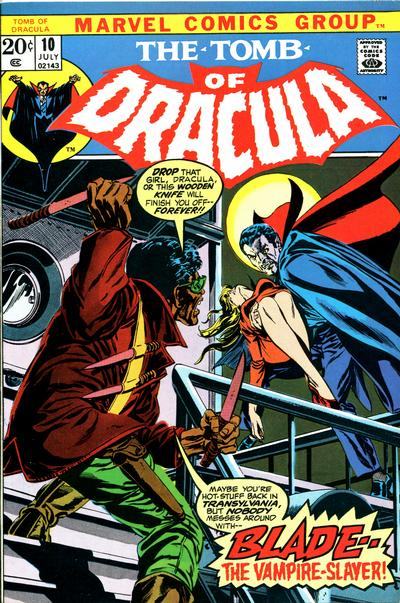

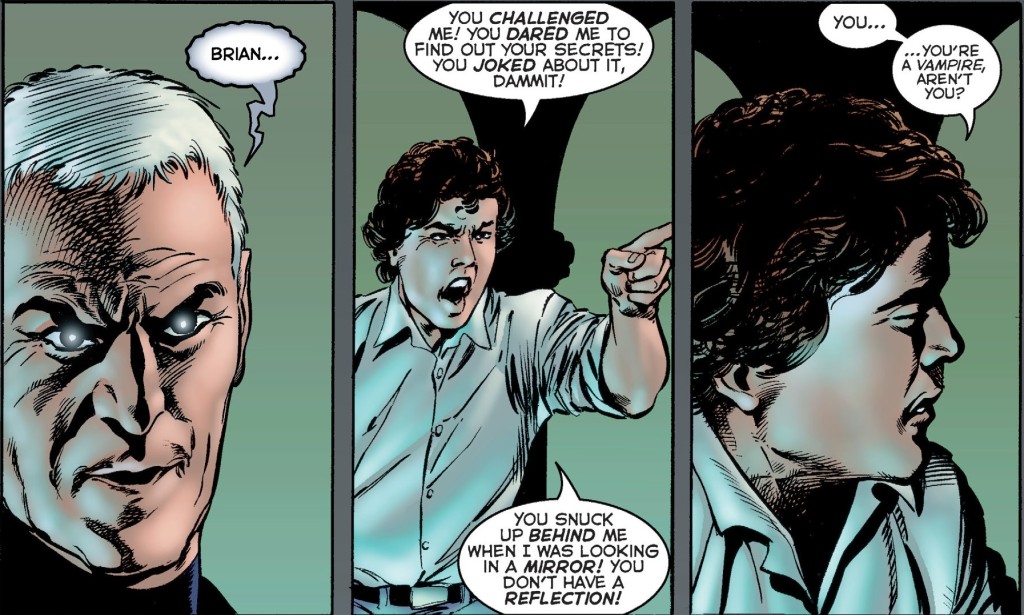

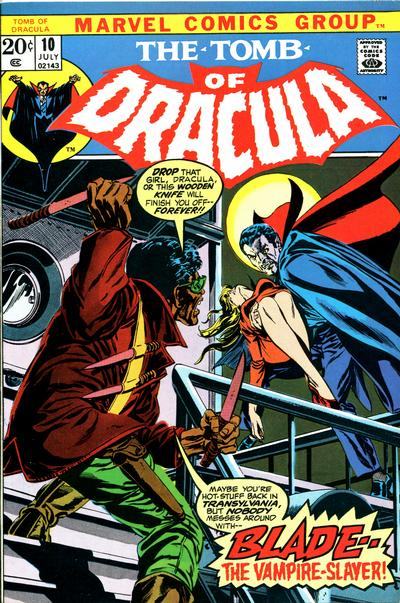

A shamelessly fun ride, Blade wastes no time on pointless origins, throwing viewers into a fully-developed world of underground vampire clubs and secret societies while trusting you to be familiar with enough of these tropes not to need too much guidance. The plot is nothing to write home about, but David S. Goyer did fill the script with some interesting ideas, like a specific type of vampiric racism or the generation clash between the gloomy old guard and the younger crowd who mostly wants to party (it’s as if the vampires of classic literature had to put up with all the millennial goths inspired by Neil Gaiman). Goyer also mercilessly reinvented the character created by Marv Wolfman and Gene Colan way back in 1973’s The Tomb of Dracula #10 (in fact, the film’s depiction ended up having a greater influence on the comics than the other way around).

You can argue that Blade is not exactly a superhero – he doesn’t have a secret identity, wear a mask, or display any reticence about slaughtering his opponents. Still, he has supernatural powers, a schlocky arsenal (a deadly silver boomerang, hollow point bullets filled with garlic), and finds himself saving the world from a monster, so I think he fits pretty comfortably in the genre. As for the horror side of the equation, the ‘blood rave party’ scene early on perfectly sets the tone with its mix of relentless gorefest and pitch-black comedy.

Following Blade’s success, David Goyer scripted a couple of sequels, both of them lacking the original’s freshness and manic energy. Although they expanded the franchise’s mythology, they didn’t do it in particularly creative ways. 2002’s Blade II was directed by Guillermo del Toro, so at least it had a couple of neat visuals (especially the vaginal-looking design of the new breed of vampires). 2004’s Blade: Trinity, directed by Goyer himself, has a deservedly poor reputation, but it works as serviceable trashy entertainment if you’re in the right mood.

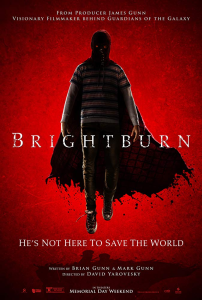

The Blade franchise marks a kind of shift that came about around the turn of the millennium. If the 1990s’ movies mostly tapped into that decade’s gothic fashion, the 21st century installments veered more into ultra-violence and psychological horror. This is in part due to David Goyer, who actually went on to shape much of the latest upsurge of superhorror, having become one of the architects of the DC Extended Universe (on top of producing a couple of Ghost Rider flicks, which I haven’t seen but, given the source material, I assume fall well within this subgenre). Most notably, Goyer scripted 2013’s Man of Steel, directed by Zack Snyder (who had made his film debut with a pointless remake of Dawn of the Dead). That controversial blockbuster sought to put a bleak, terrifying spin on the Superman mythos – an approach that David Yarovesky took even further in this year’s (regrettably uninspired) Brightburn.

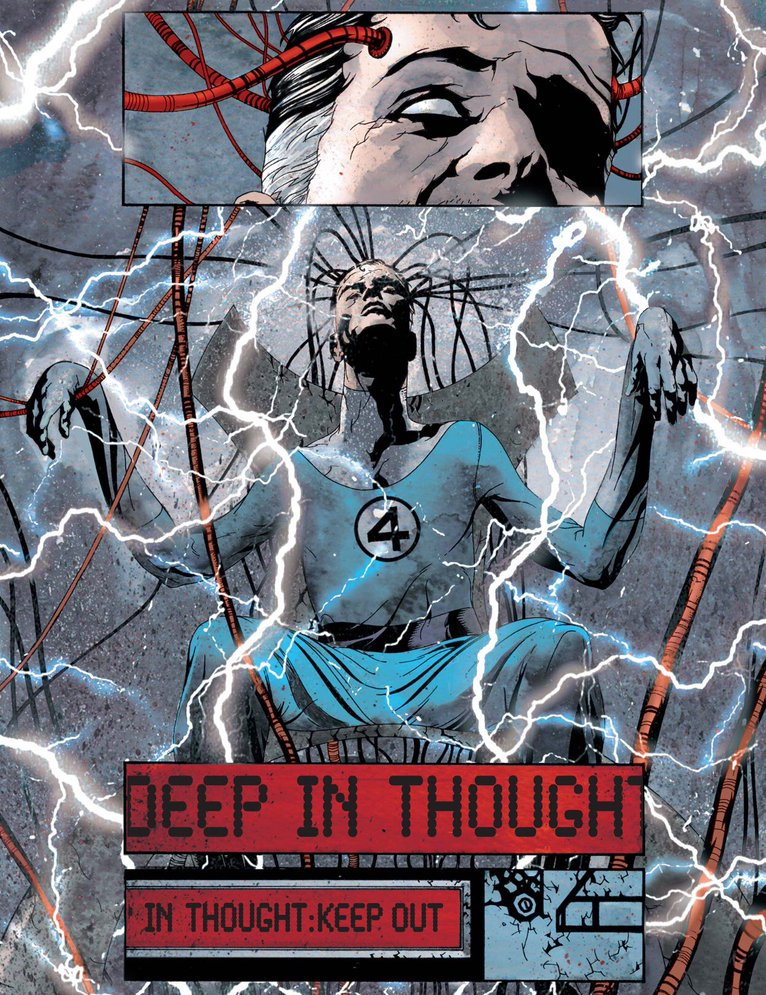

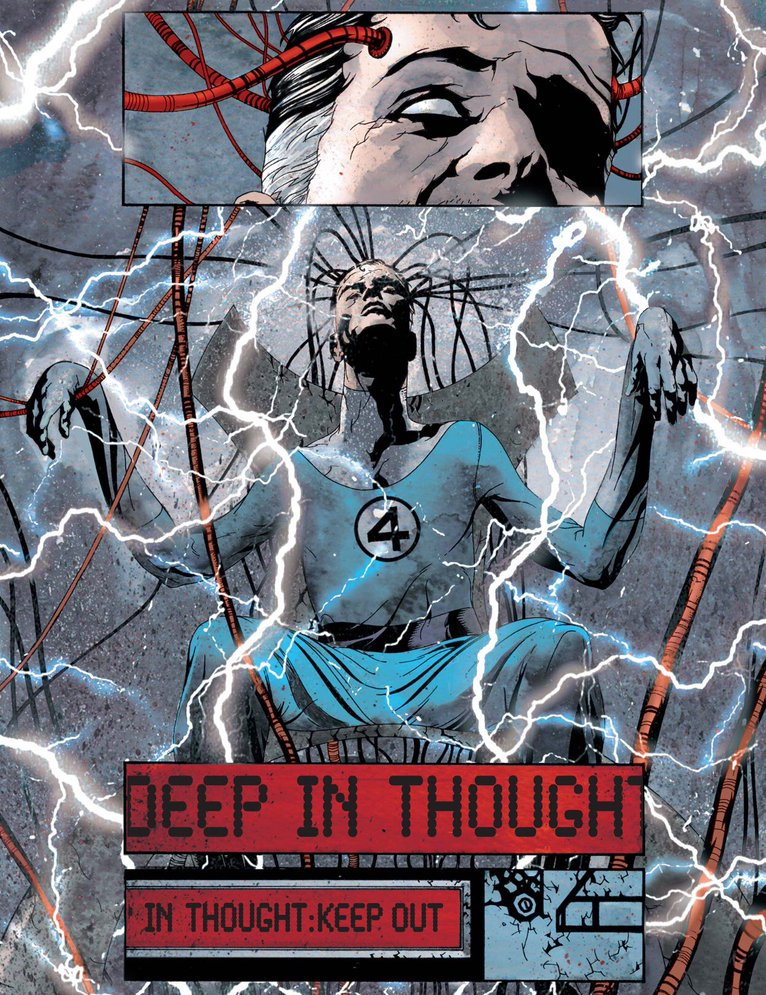

Not long after Man of Steel, Josh Trank shot some of 2015’s Fantastic Four like Cronenbergian body horror, presumably building up on what Goyer and Snyder had done with Superman (although perhaps he was merely inspired by Jae Lee’s haunting art in the Fantastic Four: 1234 mini-series…). It wasn’t Trank’s first foray into this field: he had previously directed 2012’s Chronicle, which viciously merged the subgenres of teen superheroes and found footage horror. His Fantastic Four, however, was a flop, either because it was notoriously botched in postproduction or because mainstream audiences weren’t all that keen for a gritty reboot of Marvel’s First Family.

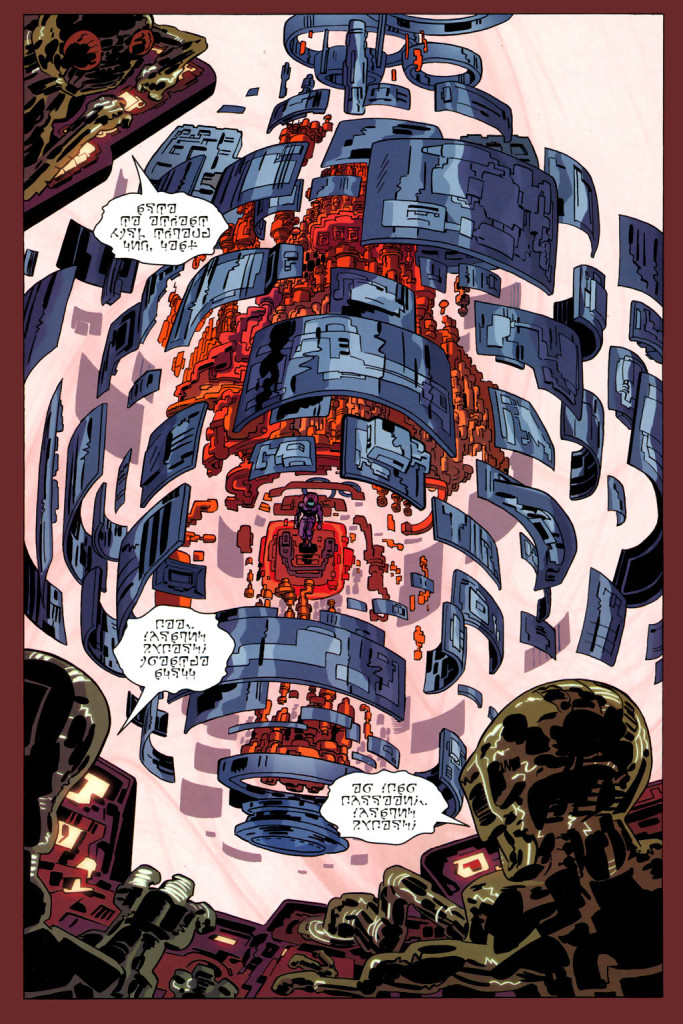

Fantastic Four: 1234 #1

Fantastic Four: 1234 #1

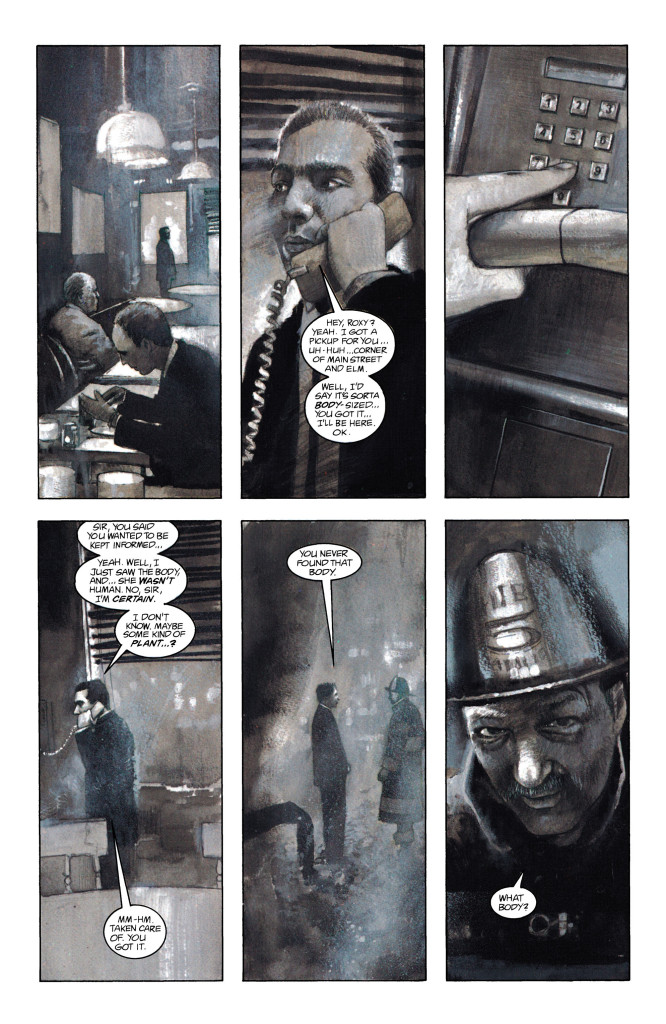

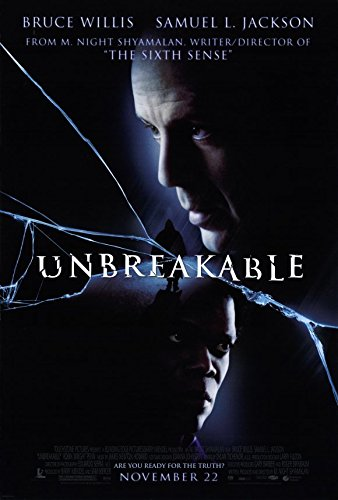

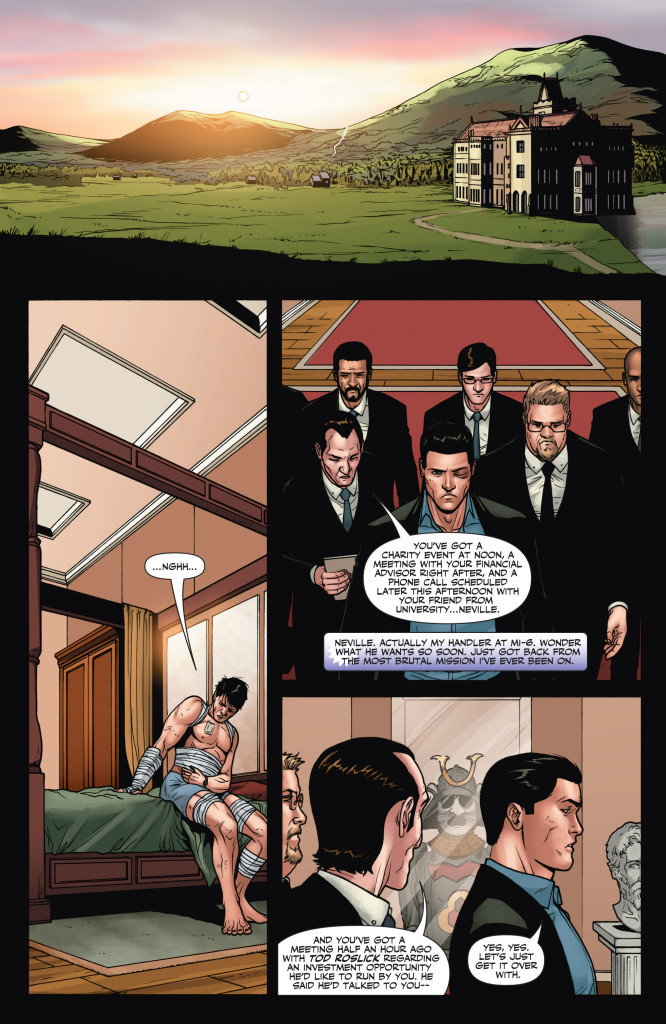

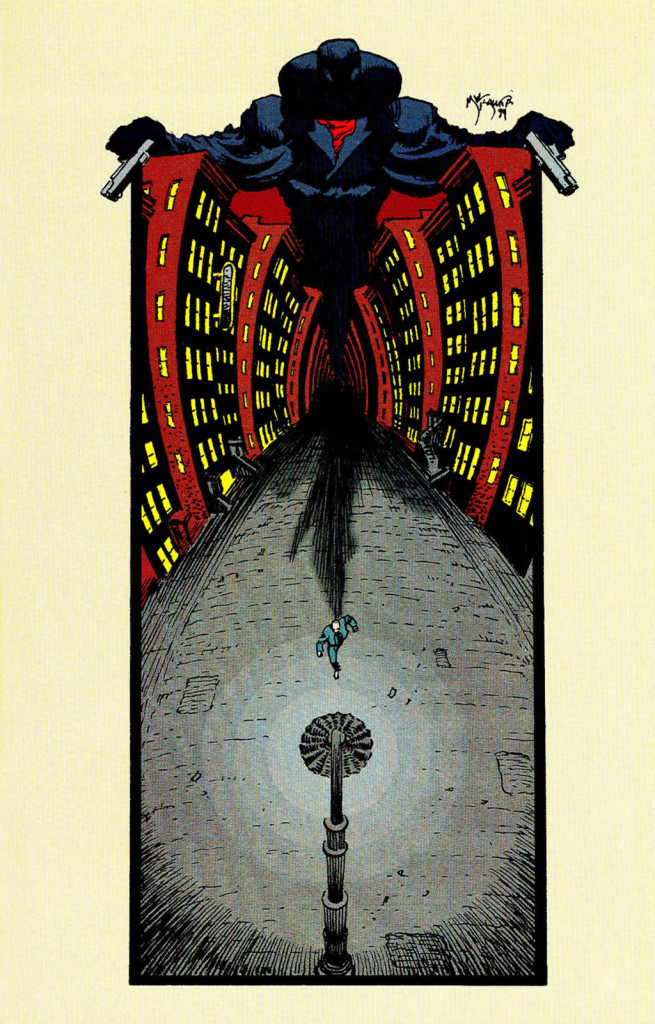

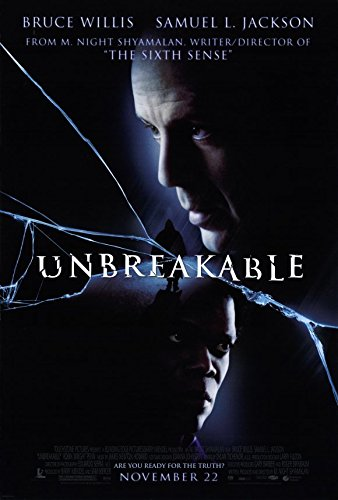

In order to look at a much more interesting take on superhero horror, we have to go back to 2000’s Unbreakable, in which middle-aged security guard David Dunn (Bruce Willis) gradually realizes he has super powers. This understated, slow-burn psychological thriller was written and directed by M. Night Shyamalan back when he was on top of the world, before becoming mostly a widespread pop culture joke. Shyamalan’s artistic fall from grace occurred at different stages for different people (for some with Signs, for many with The Village, for most – including me – with either Lady in the Lake or The Happening), but I would go so far as to say that Unbreakable is his greatest work, complete with top-notch acting, thoughtful characterization, and tight direction (including, early on, a Hitchcockian long take inside the Eastrail 177 train that is a masterful example of cinematic storytelling).

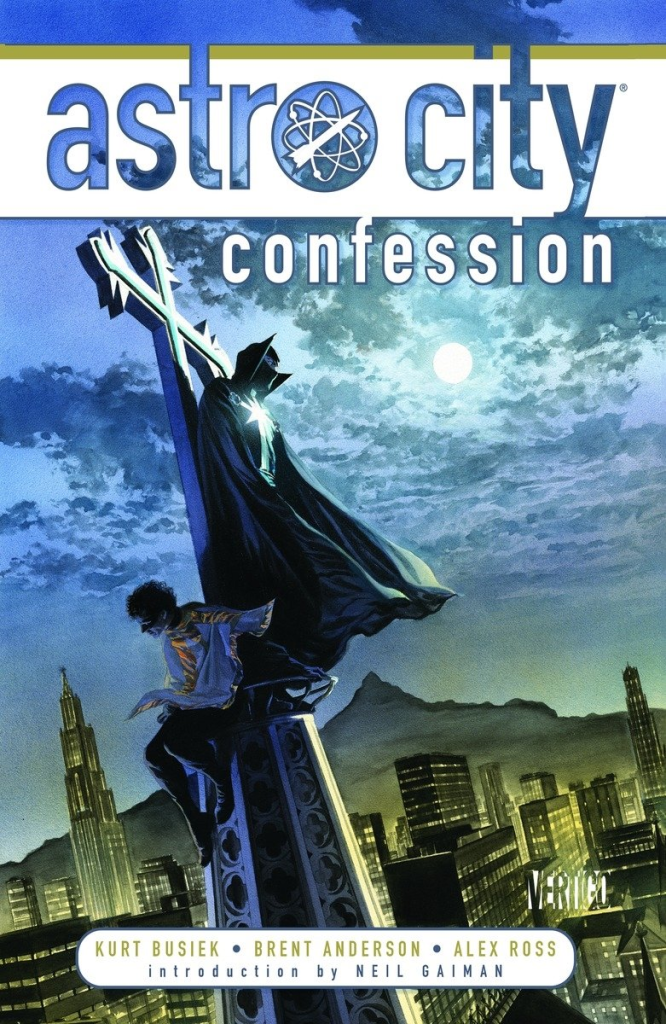

One way to look at this movie is to see it as way ahead of its time. With its drab colors, depressing tone, deliberate lack of action, and proto-realistic approach to superheroes, Unbreakable was a piece of genre deconstructionism before superheroes became a recognizable mainstream film genre (sure, there had been Superman and Batman blockbusters in the past, but those were the exception, not the rule). However, if the movie had been released today, when audiences are so used to superhero origin stories and even to tense, down-to-earth approaches to the genre (like Marvel’s Netflix shows), I don’t think Unbreakable would’ve had nearly the same shocking impact. So perhaps it makes more sense to regard it as an extension of adult, revisionist comics like Watchmen or Neil Gaiman’s and Dave McKean’s Black Orchid, pushing their sensibilities even further by bringing to the screen a truly mundane, flesh and blood superhuman, filmed through discrete travelling shots that do not evoke the comic book format.

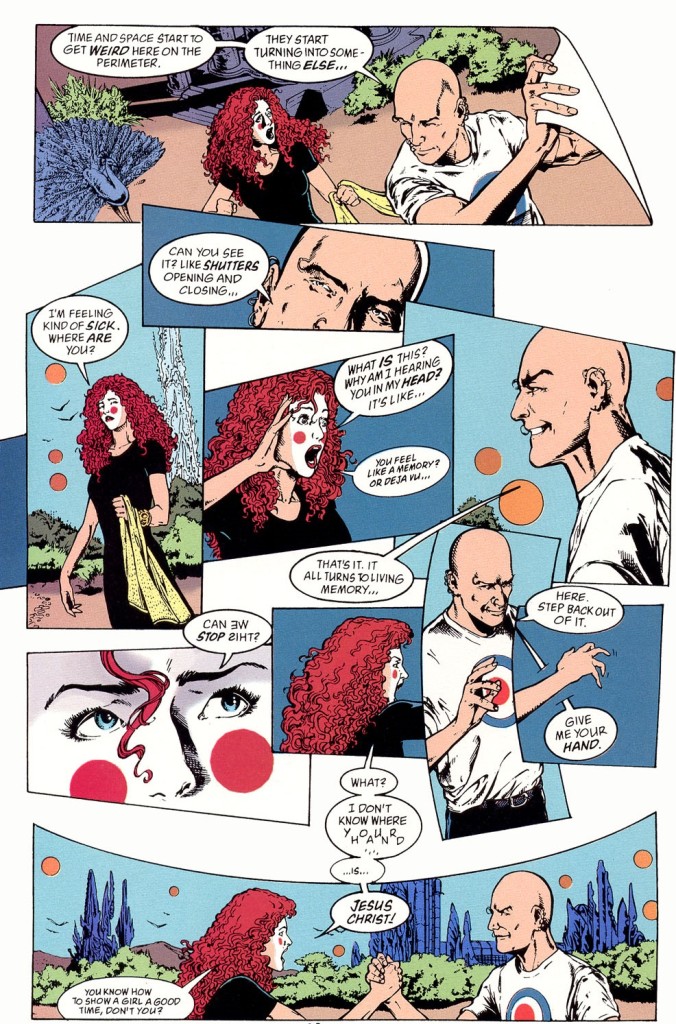

Black Orchid #1

Black Orchid #1

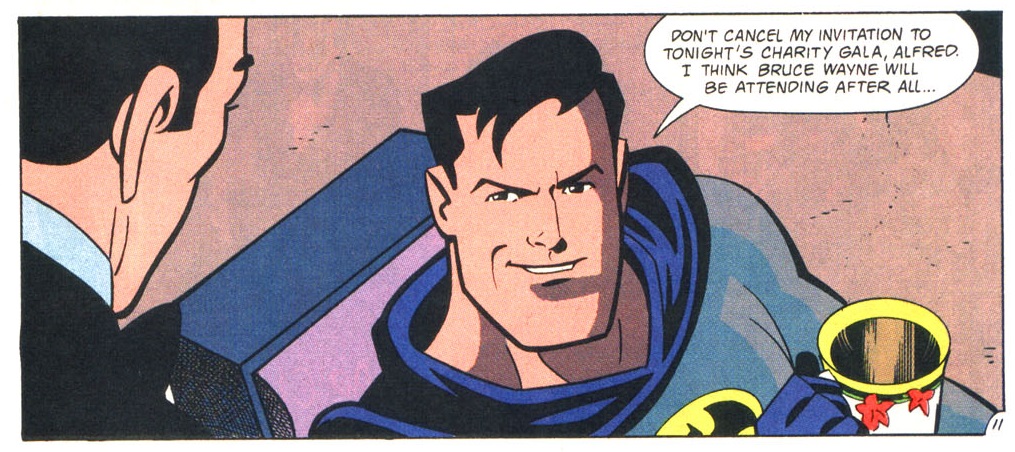

That said, at the end of the day I don’t think comic geeks were M. Night Shyamalan’s main target audience here (hence the opening text explaining to viewers that comics are a big deal). Rather, the point of Unbreakable was precisely to disguise, for as long as possible, its superhero narrative. Shyamalan’s breakout feature, the previous year’s The Sixth Sense, had been a massively acclaimed horror picture with a satisfying surprise ending. Audiences coming to Unbreakable – even those who had seen the trailers – were bound to expect a supernatural tale along the same lines and the film’s eerie, suspenseful tone led them further in that direction. The twist this time around was that they had been tricked into enjoying a superhero movie (a concept that at the time brought to mind Joel Schumacher’s infamous, ultra-campy Batman & Robin). The final payoff clinched this idea, revealing to viewers that they had been watching an even more traditional superhero story than they had realized, albeit an exceptionally well-told one.

In 2016, M. Night Shyamalan gave us a second installment in what was to become the Eastrail 177 trilogy, Split, revolving around a creepy man with multiple personalities (James McAvoy) who kidnaped three teenage girls. If Unbreakable started out as an intimate drama that painstakingly built up towards a genre entry, Split presented itself as an unashamed spine-chiller from the get-go, kicking things off with a frightening cold open and escalating from there (Shyamalan had already embraced Blumhouse Productions’ low-budget horror house style in the previous year’s The Visit). On top of some pacing issues, the movie’s depiction of mental illness ranged from tasteless to ridiculous, but you’ve got to admire Shyamalan’s willingness to develop mind-bending, preposterous-sounding concepts with a straight face.

This time the very final twist – which I must spoil to discuss the film – was that Split was set in the same universe as Unbreakable, despite the fact that this had not been announced anywhere… It could’ve been a fan-pleasing throwaway cameo (akin to the one that unites Trading Places and Coming to America), but the implications were vaster than that. Revealing this to be a stealth sequel to a film set in a superhero universe (even if a toned-down one) recontextualized Split: instead of a regular horror tale, it retroactively became a supervillain origin.

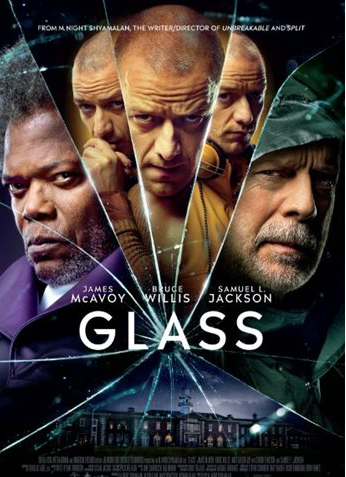

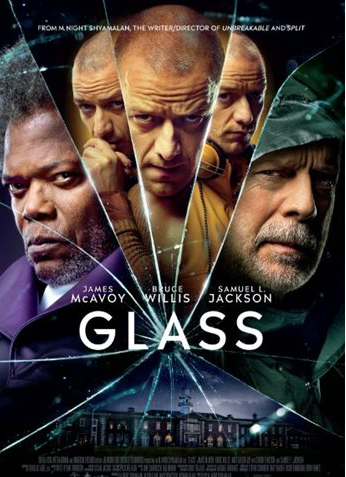

This year, Shyamalan tied the two films closer together through a third installment, Glass, which brought back the surviving cast of both Unbreakable and Split. Even if you don’t see in this move a wink to the boom of expanded superhero cinematic universes, Glass is a full-on metafictional thriller: a chunk of it is set in a mental institution for people convinced they’re similar to comic book characters where psychiatrist Ellie Staple (Sarah Paulson) analyses their alleged powers, deconstructing the fantasy and thus suggesting yet another plot twist on the previous films. The horror, in part, comes from the fact that, although the patients aren’t necessarily deluded, that is the only rational way society can look at them (apart from the signature twist endings, Shyamalan’s oeuvre also has a strong leitmotif of spirituality, the two facets ultimately celebrating in their own way the act of letting yourself believe). Staple’s counterpart – i.e. the character who goes the farthest in terms of merging comics and ‘reality’ – is the titular Glass, whose genre self-awareness means that the film does for superheroes what Scream did for slasher movies. The fact that Glass is played by none other than Samuel ‘Nick Fury’ Jackson is the icing on the cake.

The result is definitely nowhere near as brilliant as Unbreakable, but Glass is still a clever, spellbinding – if uneven – film. M. Night Shyamalan pulls off a low-key superhero crossover event filled with existential dread. And while Bruce Willis doesn’t bring the same heartfelt nuance to his performance as in the former movie, Samuel Jackson is his reliable self and James McAvoy totally commits to his bizarre part(s).

Which brings us back to Joker. On the one hand, there is no denying that Todd Phillips – like Shyamalan – plays with superhero conventions, delving into a villain’s perspective while consciously avoiding the usual overblown set pieces. Hell, with its twisted, nihilistic Clown Prince of Crime and socio-political references, Joker should replace The Dark Knight Rises as the proper final installment of Christopher Nolan’s trilogy (following The Dark Knight). On the other hand, the horror of a supervillain origin works on a different level than in Split, because with Joker we know from the start where everything is heading: trapped in a prequel about an established character, we are never allowed to imagine that the protagonist can become anything other than a genocidal jester, which gives Phillips’ psychodrama a greater fatalistic vibe, like watching the tape of a deadly crash in slow motion.

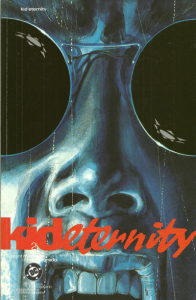

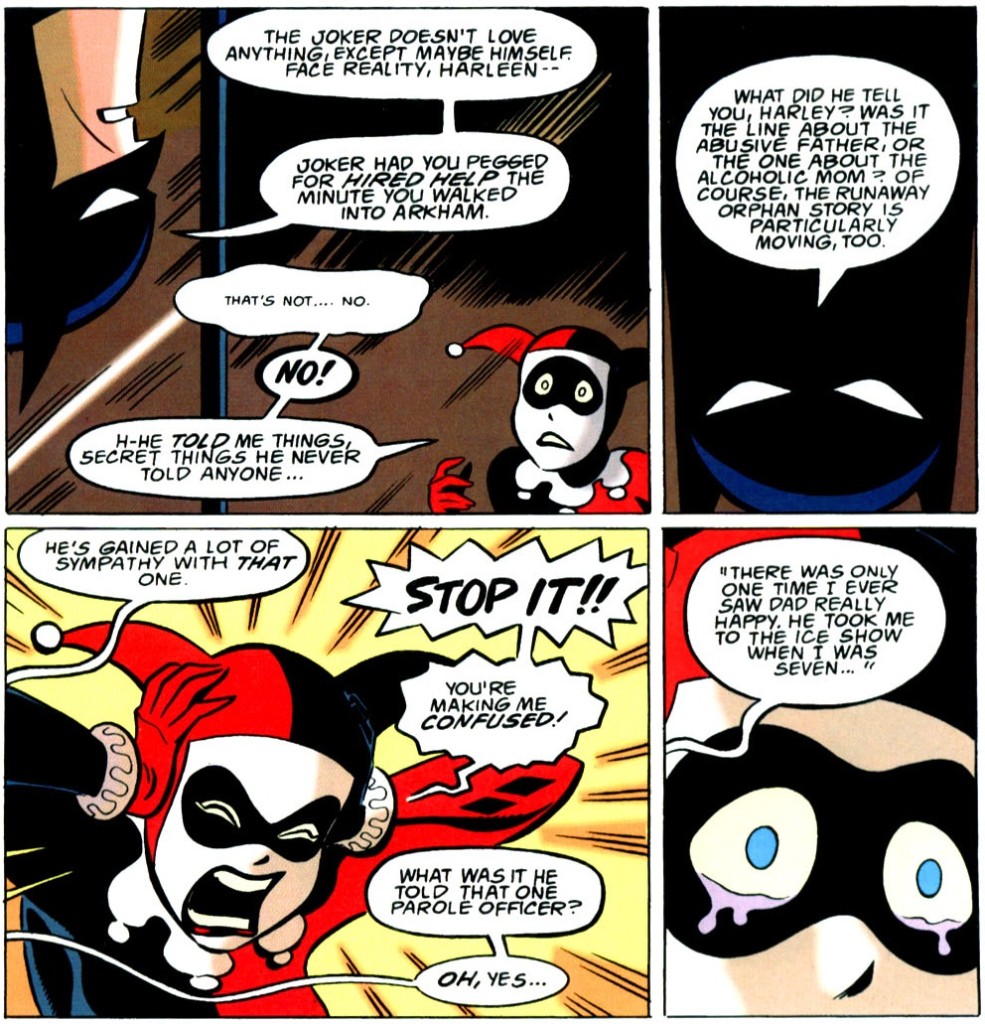

In any case, it’s quite fitting that Joker came out in the same year as Glass, signaling the growing openness of superhero films to cerebral experimentation, which mirrors what happened in the comics decades ago. Indeed, by taking superhero elements and reimagining them in an odd, sinister light, Joker and the Eastrail 177 trilogy have created for cinema the kind of provocative genre hybrids that would’ve felt at home in early 1990s’ DC/Vertigo comics – the kind written by the likes of Grant Morrison, Peter Milligan, and Jamie Delano, with art by Duncan Fegredo or Steve Pugh. Like those creators, Todd Philips and M. Night Shyamalan don’t always hit the mark, but it’s fascinating enough that they attempted to go there in the first place.