This week, a reminder that comic book covers in the 1990s were awesomely ridiculous:

…and today’s reminder that comics can be awesome is a tribute to the trippiness of old Marvel covers!

It’s time for another hiatus. I’ve been struggling to keep up with Gotham Calling’s longer posts for a while, mostly stitching together loose thoughts that I noted down here and there… Hell, I got a simple challenge in the comments months ago that I’ve been meaning to answer, but even that proved surprisingly tricky. At this stage, it’s just too hard to find the time and headspace to come up with something creative beyond recycling what I’ve written before (and, as they say, you can’t go back home). Plus, I suppose there’s a limit to how much I can think and read and write about this sort of stuff with an ongoing genocide on my mind.

Since this has always been a personal, non-commercial project, I see no need to force things further. So, yeah, I will keep up Monday’s awesome cover compilations because I still believe fun has a role to play even among desperate times, but I doubt I’ll be doing Thursday’s longer posts in the upcoming months, at least until I can put in the energy and excitement I feel the blog deserves.

That said, while I love endings, this is not one. Not yet, anyway.

2000 AD and Tornado #176

Today’s reminder that comics can be awesome is a tribute to the trippiness of old DC covers…

When I wrote about the TV series Slow Horses, last month, I mentioned how one of the departures from the source novels was that the show didn’t take advantage of the potential of sleeper agents to act as metaphors for the migrant experience. By contrast, this allegorical resonance has been all over a veritable flood of shows in the past decade dealing with Cold War-era communist moles. I’m not entirely sure who started this, but the first high-profile entry was The Americans (2013-2018), which used the premise of a couple of KGB agents raising a nuclear family in 1980s’ Washington to explore the theme of secret double lives and US immigration, as well as more specific facets of the Reagan era.

In turn, The Americans had a pretty crude understanding of communism and of the Cold War as a whole. At least in the few episodes I watched, the conflict came off as a relatively traditional war between nations (the ‘motherland’), devoid of a distinct ideological dimension. Plus, outside of the internally torn protagonists, the Soviets were such brazenly vile cardboard caricatures that I couldn’t really buy into the couple’s loyalty to the USSR beyond basic notions of brainwashing… Ironically, it’s as if the show just bought into the mindset of the very era it was portraying, without any critical distance.

The same tendency can be seen abroad, most notably in the Portuguese Glória (2021) as well as in the German Deutschland 83 and its two sequels, Deutschland 86 and Deutschland 89 (2015-2020). As pure thrillers, these shows have a lot going for them, what with the stylish direction, knotty intrigue, and killer soundtrack, in addition to some truly original settings, ranging from a Radio Free Europe operation in 1960s’ Portugal to arms deals in 1980s’ northern and southern Africa (including a venture into the Angolan Civil War, which was a conflict with so many different players and odd alliances that it’s a wonder it doesn’t pop up more often in the genre).

In both cases, the hook is great, as the protagonists are working for the KGB and the Stasi’s HVA, respectively, so the results could’ve been perversely challenging, getting us invested in a view of the Cold War that runs counter to that of most western spy fiction. Sadly, though, the shows don’t live up to this potential. Glória comes the closest, but the very fact that it paints the local resistance against Portugal’s fascist regime and colonial wars as largely subordinate to – callous and murderous – Soviet agents ends up reproducing the very propaganda of the Portuguese dictatorship. Similarly, Deutschland ticks all the boxes of West German conservative rhetoric (it even accuses the peace movement of being naively manipulated by gay GDR infiltrators) and never misses a chance to mock East Germany’s orthodoxy, immorality, and poverty in a way that smacks of Schadenfreude.

While there could be dramatic appeal in the tale of a desperate intelligence service (which has to count pennies after Gorbachev reduces Soviet support) fighting what we now know to be a losing fight, for that to work the East Germans had to be anti-heroes to some extent rather than fully pathetic and contemptible all the time. Granted, some of Deutschland’s mockery is quite funny (like when they steal a floppy disk but have no clue what to do with it) and much of it deserved… But the show actually goes out of its way to score political points, as if it’s still fighting the Cold War after all these years – it seems less interested in telling a rich account of the past that takes in the conflict’s contradictions and ambiguities than in demonstrating the West’s superiority (except for the French, who are also assholes). Perhaps the creators just don’t trust the audience, fearing we will forget and forgive all that was bad about the GDR if we get even the slightest glimpse of unsoiled humanity and idealism.

Thus, if in the first season the East Germans appear as responsible for the Able Archer 83 scare that may have brought the world closer than ever to thermonuclear war, the second season manages to twist one of the areas where the GDR was on the ‘best’ side of history, having backed up anticolonialism in Africa… Bafflingly, Deutschland 86 has them cynically supplying weapons to apartheid South Africa (which could have been an amusing bit of counterintuitive comedy if the show wasn’t so committedly one-sided) while, more predictably, making a point to emphasize their connections to Libyan terrorism. Plus, in an extra reactionary touch, the featured black Africans mostly lack agency in the proceedings, essentially acting as puppets of the whites (just like western propaganda used to argue).

To be fair, by the time we get to the third season, Deutschland 89, we’ve followed these characters for so long that something touching slips through as they see their entire world crumble along with the Berlin Wall. There is some further ideological confusion (the show seems unaware that, by then, Italy’s PCI was no longer a pro-Soviet communist party) and, once again, the Left appears as utterly sinister and/or hypocritical while the Right escapes largely unscathed, despite a few jabs near the very end. At least there is a fairly neat moment when an East German visionary tries to start a business of computers with pre-installed cameras, only to be told that the whole notion is just too Stasi-like… Still, we certainly remain far, far away from the nuanced satire of 2003’s Good Bye Lenin!

By contrast, the Romanian series Spy/Master (2023) is everything I wanted. Set in the late 1970s, this heavily fictionalized version of Ion Mihai Pacepa’s defection also follows an undercover KGB agent, but with the extra twist that he is infiltrated in another communist country, namely Romania (which had excluded the Soviets from its foreign policy in 1964). Add to this subplots about corruption, interdepartmental paranoia, Middle East peace talks, and the involvement of the secret services of half a dozen different countries. The result is an elaborate tapestry that tells a much more stimulating story than the traditional East vs West dichotomy… and which Spy/Master pulls off through a highly effective economy of information, expertly weaving the various threads (even as it continuously jumps back and forth in time!) and letting things play out without preaching.

Alternatively, if you like your spy fiction with a dryer, colder, darker, more slow-burn atmosphere, you may prefer the Czech The Sleepers (2019). Mostly set on the eve of 1989’s Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia, this mini-series features the usual bits of tradecraft (dead drops, triple agents, counter-surveillance maneuvers to throw off pursuers), but subsumes them in greater dramatic complexity and melancholia. In contrast to the triumphalist pop euphoria of Deutschland 89, here we get a fascinatingly unconventional portrayal of communism’s final days: the characters – especially those working for the secret police StB – feel on the verge of a massive historical change (Poland and Hungary have fallen, the GDR seems on the way) without quite knowing what lies ahead, so the general mood is one of cloudy alienation and uncertainty. What’s more, because this is a 21st-century show, it also retroactively anticipates elements of the then-future/now-present (like the troubled relation with Russia), offering a disenchanted outlook of the transition into liberal democracy, with the country (now two countries) persistently spied upon and manipulated by foreign forces.

I don’t know whether there is something in the air or if it’s just some algorithm telling Netflix and HBO to co-fund this type of productions, but, regardless, one of the positive side effects of the popularity of all these foreign spy series about lesser-known historical episodes is that mainstream media is finally projecting, in one way or another, the fact that the Cold War was a global conflict involving many other players beyond the superpowers. (Although not exactly a spy thriller, I would add to this list the Finnish Invisible Heroes (2019), about Scandinavian diplomats who find themselves in the middle of the 1973 coup in Chile.) We’re used to seeing Czechoslovakia, Romania, Germany, or Portugal as chessboard pieces in the geostrategy of the CIA, KGB, and MI6, but by mostly focusing on the locals’ experiences and perspectives, we’ve now been increasingly presented with a different, humanizing picture in which Cold War games appear as even more sinister and intrusive.

More recently, the awesome filmmaker Park Chan-wook put his own gonzo spin on the red mole subgenre with The Sympathizer (2024), based on Viet Thanh Nguyen’s best-seller about a North-Vietnamese agent infiltrated in South Vietnam and, eventually, in the United States. Again, we have a mole who can’t help being a mole, his greatest asset also being his greatest peril, namely the fact he’s ultimately torn between two worlds, feeling more comfortable on enemy ground than in his home turf. Yet here the vibe is much more iconoclastic: kicking off just before 1975’s fall of Saigon (which has gained a renewed impact since 2021’s fall of Kabul), the show takes the piss out of all the sides in the conflict with manic, contagious glee, unafraid of indulging in tasteless absurdity… Park Chan-wook even works in his typical obsession with food and, especially, mollusks (including a bit about squids that will sit in my memory next to the octopuses of Oldboy and The Handmaiden) while executive producer Robert Downey Jr keeps showing up in multiple roles, each one more caricatural than the previous one.

I wasn’t the biggest fan of Park Chan-wook’s adaptation of Little Drummer Girl, but here I think he found the right material on which to apply his baroque touch. If the former seemed like a weird homage to theatre, this one provides a suitable celebration of film language, from rhythmic tracking shots to stream-of-consciousness rewinds and cheeky visual transitions. In part, the quasi-surreal approach works because over the years the Vietnam War has been reduced to such stylized, recognizable imagery in American pop culture, something that The Sympathizer self-reflexively engages with in the wonderful fourth episode (directed by Fernando Meirelles), set in Hollywood. It is to the show’s credit that it somehow manages pull off actual pathos among all the vicious chaos, matryoshka-like narrative, metafiction, and Tropic Thunder-esque black comedy.

That said, it’s not as if you can’t do an earnest, intelligent take on the old East-vs-West bipolarity. Even setting aside the espionage dimension of the alt-history saga For All Mankind (2019-2024), two of the most brilliant series in recent years did so. BBC’s The Game (2014) was set in 1972 and concerned an elaborate counterintelligence operation against an ominous Soviet conspiracy in the UK. Also from Britain, A Spy Among Friends (2022) was a loose adaptation of a non-fiction book about Kim Philby’s defection to the USSR, focusing in particular on his ambiguous escape from Beirut in 1963.

Both series are superb, but the latter is especially well written, acted, and edited. At first, I feared the project was just going to add up to yet another retread of this much trodden case – which has been dramatized and fictionalized to death – but I was very positively surprised: besides being engrossingly intricate (i.e. definitely binge-worthy) and sophisticated in tone (despite a gratuitous Goldfinger joke in episode 2), the story adds a poignant revisionist twist which – not unlike Robert Harris’ Munich – derives its force precisely from of our knowledge about the future and our likely prejudices cemented over time.

While A Spy Among Friends does not avoid the cliché of irredeemably unlikable Soviet villains, at least it recognizes the danger in the paranoia, division, and elitism at home… The show follows John le Carré’s class-based interpretation that Kim Philby got away with his double dealings for so long because the British establishment was so used to disregarding/covering up the shadiest elements of the ‘inner circle.’ In fact, I would argue this series truly earns its place among the extensive intertextual dialogue about Philby by the likes of le Carré and Graham Greene. And, needless to say, it’s impossible to watch it now without thinking of the current relation with Russia, making one hope that the Cold War remains a thing of the past… and of damn good fiction.

Last time, I finished with nod to a whole other take on the genre, more focused on escapist thrills than in real-world politics. And, sure enough, there have also been occasional throwbacks to the sort of super-spy yarns that were all the rage in the swinging sixties (particularly in Europe). In this regard, I actually had high hopes for Pennyworth (2019-2022), a show that seemed designed from scratch to be discussed in Gotham Calling, as it is a period piece spy thriller premised on a hilariously pointless deep cut of Batman lore (they even subtitled it The Origin of Batman’s Butler) that gradually ties into an Alan Moore comic! Set in a heightened-reality quasi-gothic alternate 1960s London riddled with conspiracies and secret societies, this prequel to Gotham was similarly – and unabashedly – artificial: there were some nice lines buried among the many clichés and forced British slang, yet the whole thing was so overplayed that it became a generally unpleasant, ultra-violent, thick-lined cartoon, as if written by edgelord teenagers who have heard of adult concepts (class division, fascism, the Malayan Emergency…) without fully grasping them. Ultimately, Pennyworth tried too damn hard to be cool (which, ironically, is uncool) and it veered too closely into just my sort of stuff for me not to notice when it was missing the mark.

As far as I’m concerned, the gold standard for rip-roaring spy-fi adventure on the small screen remains Agent Carter (2015-2016), MCU’s spin-off of Captain America: The First Avenger set in 1940s New York City (and later Los Angeles). The hook was that Peggy Carter, instead of getting pushed into domesticity like many women in the postwar years, struggled to continue kicking ass as an agent of the Strategic Scientific Reserve (S.H.I.E.L.D.’s predecessor). Now, I’m already a sucker for the trope of the underestimated woman who proves everybody wrong, but Agent Carter approached it in a particularly satisfying way, not only because of the historical background, but also because this choice always felt organic rather than preachy… The trope was cleverly put in the service of humor, characterization, and storytelling.

Another effectively deployed trope is the figure of the psycho Russian killer who develops a sort of fascination and mutual recognition regarding the hero – a dynamic that revisits Cold War stereotypes (hell, it’s practically a metaphor for the Cold War itself!) while also anticipating Killing Eve (which actually has quite a bit in common with Agent Carter). But whereas the latter show pushed wickedness to a point where it often became frightening and even disturbing, the former mostly kept the focus on bouncy action and lighthearted comedy.

Indeed, this show nailed such a specific witty vibe and engaging cast that it baffles me why Agent Carter hasn’t become a regular comic, even after Kathryn Immonen and Rich Ellis have proven how well it could work with a fun mini-series back in 2015, followed by a special.

Agent Carter: S.H.I.E.L.D. 50th Anniversary

With the return of the Mad Max and Planet of the Apes franchises – and perhaps as a way to occasionally escape the present-day horror – my mind has been on futuristic fiction. Consequently, this week’s reminder that comic book covers can be awesome is a tribute to Batman Beyond, particularly the use of striking colors to convey a digital, high-tech, neon-drenched vision of the future:

Black Condor #12

Turning Points #1

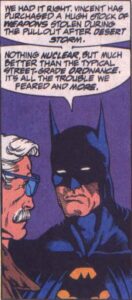

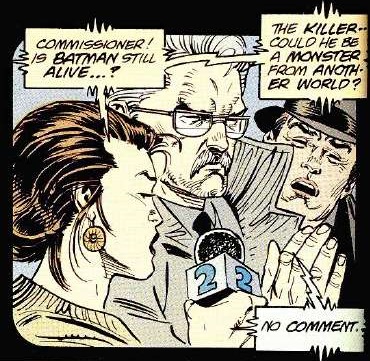

Batman Annual #21

JLA: Incarnations #2

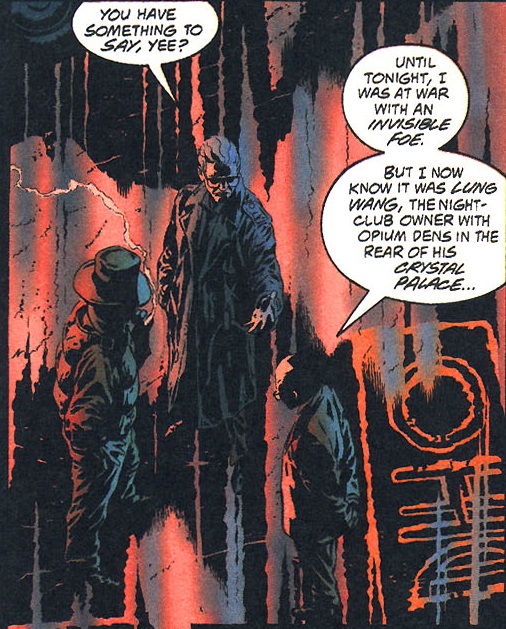

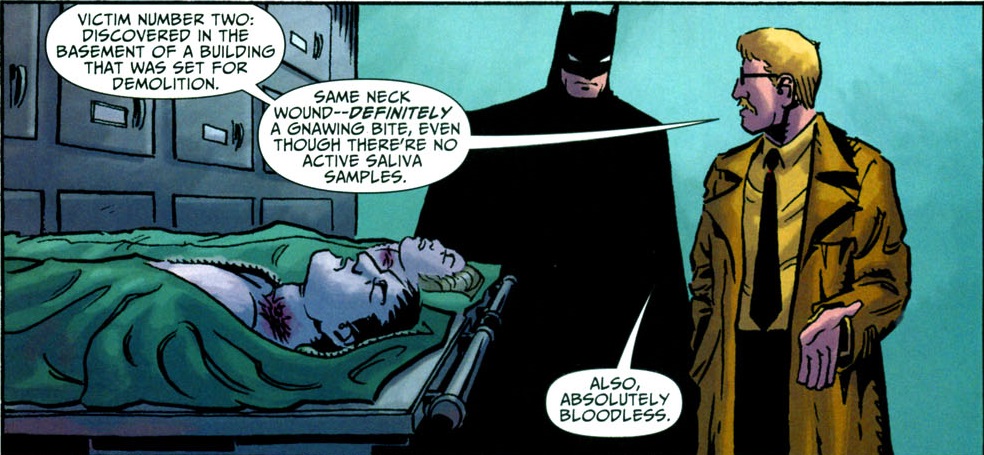

Legends of the Dark Knight #95

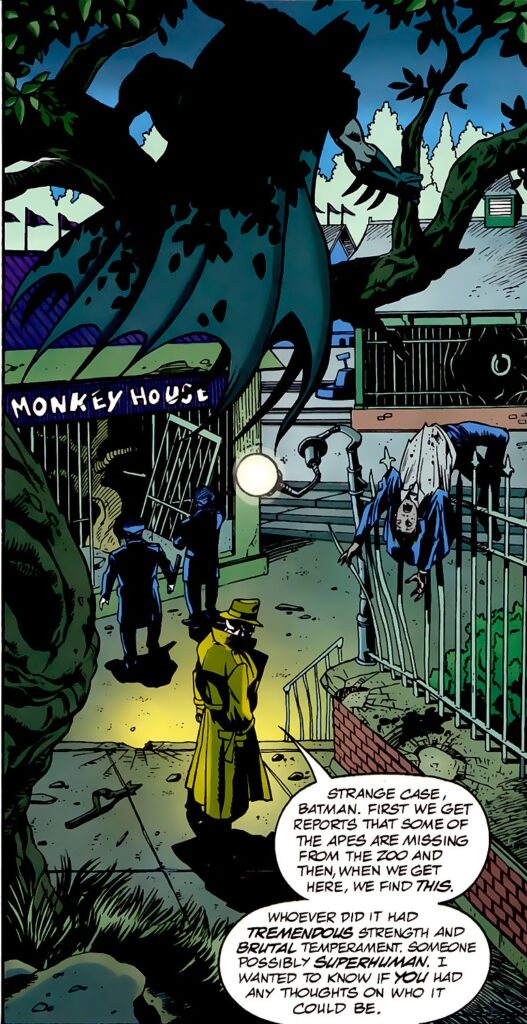

Batman and the Mad Monk #1

Batman versus Predator #2

Another week, another tribute to the captivatingly stylish sense of design you can find in comic book covers:

As mentioned last week, I’ve been rereading the first decade of René Goscinny’s run on the Belgian series Lucky Luke, illustrated by Morris, and trying to figure out what made those comics work (and why they resonated so much with me when I was younger).

The Black Hills

On the one hand, the books were more comedies than proper parodies, as many of the character traits and situations were droll by themselves, without requiring deep referentiality. Moreover, instead of mocking recognizable narratives, if anything the plots seemed to pay tribute to them. The Wagon Train was a serviceable whodunit set in a caravan headed for California. The excellent The 20th Cavalry presented a tense escalation of conflict between the cavalry and the Cheyenne. In Calamity Jane, ostensibly separate A and B plots were masterly interwoven before simultaneously paying off at the end.

In fact, after a while, Goscinny’s plots became so elaborate that they sometimes worked almost as ‘pure’ westerns that happened to contain tongue-in-cheek gags. The result was not too dissimilar to films that, while not outright comedies, have a consciously playful vein running through them, such as Destry Rides Again, Ride a Crooked Trail, or Heller in Pink Tights. Hell, if you tone down the deadly violence, spaghetti westerns like Sartana’s Here… Trade Your Pistol for a Coffin – not to mention They Call Me Trinity and its sequels – could practically pass as Lucky Luke entries.

Take The Black Hills, where Lucky Luke is tasked with escorting a scientific expedition into Wyoming in order to prepare the territory for settlement, basically taking over the land controlled by the Cheyenne (‘Let us proclaim that civilization must cross the Black Hills!’). It’s a boisterous adventure full of laughs and thrills, even if the hero is trying to push forward Western settler colonialism and the villains are seemingly trying to prevent it…

The Black Hills

To be fair, it’s a bit more complicated than that. For one thing, the senator you see opposing the expedition is just trying to safeguard his own shady business interests (‘He sold guns and alcohol to the Indians, and he was afraid that civilization would ruin his trade…’). Although you can say the Cheyenne, led by Chief Yellow Dog, start out infantilized (in a slightly different way than almost all Lucky Luke characters are infantilized, because playing on existing prejudices), the album makes it clear that a) the Cheyenne have been corrupted by greedy white capitalists, and b) they could ultimately excel at Western notions of institutionalized knowledge (it’s the book’s final punchline).

Rather than looking for a specific moral angle or ideological perspective, though, you can also just approach The Black Hills – and the rest of the series, really – as a whimsical retelling of brutal historical processes, with the primary joke being the very act of making light of them by having everyone involved coming across as utterly silly.

For instance, this is Lucky Luke’s version of North-American imperialism in Mexico:

Tortillas for the Daltons

That said, some of the humor comes down to sheer execution. If you go back to the second scan from The Black Hills, you’ll notice there is a droll progression in the first three panels, amusingly contrasting Lucky Luke’s horse, hat, and demeanor (symbolizing the Wild West) with Washington’s more formal, austere modernity.

You can find plenty of similar gags in the (sort of) sequel, The 20th Cavalry. There, Yellow Dog is once again tricked by a white guy into declaring war, but he’s not necessarily more foolish than anyone else:

The 20th Cavalry

The composition in these pages is just one of many examples where the team of Goscinny & Morris came up with effective visual techniques to deliver their jokes… For another example, check out how shifting panel lengths in the sequence below (from Joss Jamon’s Gang) provide the necessary timing and fluidity to sell an apparently simple gag:

Joss Jamon’s Gang

The scene doesn’t stop there. Having established the dynamic of the situation and the geography of the saloon, the page continues in a way that takes advantage of readers’ awareness of these two aspects in order to indirectly suggest what happens off-panel (thus letting us imagine the literal punchline):

Joss Jamon’s Gang

As you can tell by now, saloons are a major setting in Lucky Luke, so Morris’ varied mise-en-scène is also a way to prevent visual boredom…

Below you can find yet another example from Joss Jamon’s Gang, set in this same saloon, later on. It’s a sequence that really nails how thoughtful framing can elevate a joke. Basically, we’re dealing with a classic premise in which a large group of people all have the same reaction at the same time (with one comical exception). Once again, Morris pulls it off through the way he frames the action, underling the collective dimension:

Joss Jamon’s Gang

On the other hand (yep, I’m finally complementing the thought from the beginning of this post), some elements *were* deliberately satirical. For one thing, Lucky Luke painted the Old West through the broadest – and most unflattering – of brushstrokes, conjuring up a whole culture that seemed to largely revolve around stupid, venal men drinking, fighting, and pointlessly killing each other.

This was taken to a surrealist minimalistic extreme in The Escort:

The Escort

Such over-the-top exaggeration may be read as a mere satire of the western genre, itself prone to reduce the final decades of the 19th century to a limited amount of stock characters and tropes. But it’s also not too much of a stretch to find in the series a satire of America – or even of humanity in general, with its history of violent conflicts, especially over property.

Plenty of stories revolve around land disputes in one way or another. In one album, Lucky Luke sides with farmers against the local cattle breeders (even though he is ostensibly a cowboy himself) and the main source of ridicule is that, in such a heated dispute, putting up a barbed wire fence becomes tantamount to an act of war…

Barbed Wire on the Prairie

René Goscinny was certainly a politicized figure. In 1956, along with Charlier and Uderzo, he called upon Belgian artists to sign a charter to strengthen the professional status of comic creators. In retaliation, the three of them were fired by their publishers. They then created an independent company, Edipresse-Edifrance, and in 1959 founded the magazine Pilote. Named editor-in-chief in 1963, Goscinny changed the magazine’s target audience from children to teenagers – and you can see the same looser, rebellious spirit in his work on Lucky Luke (at the time still being published by the mainstream publisher Dupuis).

In both Joss Jamon’s Gang and The Judge, the criminals become institutionalized, so the (black) comedy derives from a caricature of corrupt, despotic authorities. Joss Jamon’s gang don’t just rob the bank – they take over the bank and, gradually, over every business in Frontier Town. Soon, Jamon decides to become Mayor (‘We’ll expand our empire over the whole state… and maybe, who knows, over the whole country…’), leading to this mockery of democracy:

Joss Jamon’s Gang

(The main joke is rampant authoritarianism, of course, but also the way Morris and Goscinny use the elliptical language of comics… the humor is not just in the situation itself, but in the abrupt transitions.)

One of the effects of the criminals’ rise to power is a curious inversion. Lucky Luke, who is often a straight man/authority figure, comes across in these albums as more of an anarchic Daffy Duck character, sabotaging the (criminal) state. Between the rigged elections, extortionary law enforcement, random arrests, and ridiculously shameless show trials, it’s hardly a stretch to see this as a satire, not just of predatory capitalism, but of the very rise of fascism (in the case of Joss Jamon’s Gang, with the Civil War as a stand-in for World War I). In that sense, Lucky Luke appears here as a force of resistance, ultimately mobilizing the people into carrying out a revolution against their oppressors. (The same goes for the album Billy the Kid, which at the end of the day is also an anti-tyranny parable.)

You get another comedic take on elections in The Oklahoma Land Rush, in which Lucky Luke is assigned with managing the land run of 1899, when settlers were authorized to take over the former Indian Territory. The main joke there, though, is how arbitrary property ownership is… It’s imposed by violence, yet people immediately feel a sense of entitlement:

The Oklahoma Land Rush

It’s a funny album that also takes potshots at familiar targets, like capitalist speculation, overexploitation of natural resources, and dizzying, out-of-control modernity, with urban institutions sprouting at lightning speed (apparently doing justice to the real-life Oklahoma City, which, according to the book’s back matter, within five weeks already had stores, a bank, a daily newspaper… and a graveyard).

And sure, once again, it’s tasteless – to say the least – to discard all the violence committed against the Native Americans killed or expelled from the land, reducing the whole process to a whimsical, friendly negotiation. At least The Oklahoma Land Rush unabashedly acknowledges that it’s a fantasy about a much more benign version of history. In the ironic ending, the real-world victims get the fictional last laugh:

The Oklahoma Land Rush

(If you’ve seen last year’s Killers of the Flower Moon, though, you know this wasn’t a happy ending as much as a new chapter in the Osages’ tragic history…)

Oil digging would itself become the target of satire a few books later. In 1962’s In the Shadow of the Derricks, Lucky Luke gets appointed sheriff of Titusville, Pennsylvania, during a rush for oil in that town. His job is to bring order into a place where everyone has gone crazy with greed and is destroying the environment by digging for oil everywhere (and, yes, the worst of the lot is a law-savvy businessman exploiting the system and using all sorts of dirty tricks to build a monopoly). It’s a wonderfully caricatural album, conjuring up yet another amusingly surreal setting, conveyed by Morris’ cinematic framings:

In the Shadow of the Derricks

Given the terrifying escalation of war, nationalism, and climate crisis, to which we can now add mass arrests of students protesting against genocide, it is not surprising that we’re in the midst of a surge of mainstream dystopias, from Civil War to the upcoming Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga – so it just seems appropriate to pay tribute to the covers of 2000 AD’s golden years with their imagination of weird, monstrous futures: