I had a blast putting together Gotham Calling’s list of top Cold War movies, as I got to dig into cinema history and unearth a slew of gems from the mid-to-late 20th century that approached geopolitics through diverse (and sometimes quite eccentric) uses of film language.

That said, it’s not as if there aren’t interesting movies coming out today… So, with that in mind, and taking for granted that the genre that best speaks to our age of immediacy is probably the thriller, with its tight control of pace and perspective, I’ve decided to spotlight half a dozen suspenseful pictures that came out in recent years and which show how this form of storytelling still has plenty to offer on the screen:

DECISION TO LEAVE

(Park Chan-wook, 2022)

I’ll try not to overuse the adjective ‘Hitchcockian,’ but it’s hard to avoid in the case of Decision to Leave, a mystery thriller about a cop who becomes enthralled by a victim’s wife (who is also a suspect). Along with the Vertigo-esque mood, there is a fascination with technology – especially smart phones – as an omnipresent source of both vital information *and* miscommunication. For all the many labyrinthic twists of a challengingly intricate plot, though, it’s single images and quiet moments that linger in the mind, as Park Chan-wook handles the material with his inimitable style, treating every frame like a carefully composed painting.

JUST 6.5

(Saeed Rousayi, 2019)

This Iranian tour-de-force about the narcotics brigade’s relentless – and often ruthless – struggle, up the food chain, to nail a major drug kingpin grabs you from the start with its gritty, documentary-like style and never lets go… The first half is pretty much The French Connection in Teheran, but halfway through the film takes a different, richer direction, humanizing the characters, critically scrutinizing the justice system, and ultimately casting doubt on what appears to be a recognizably hopeless war on drugs. In other words, not only do we get the thrills and aesthetics of Friedkin’s classic, but also a more complex emotional drama and an even more discomfiting comment on society.

THE KILLER

(David Fincher, 2023)

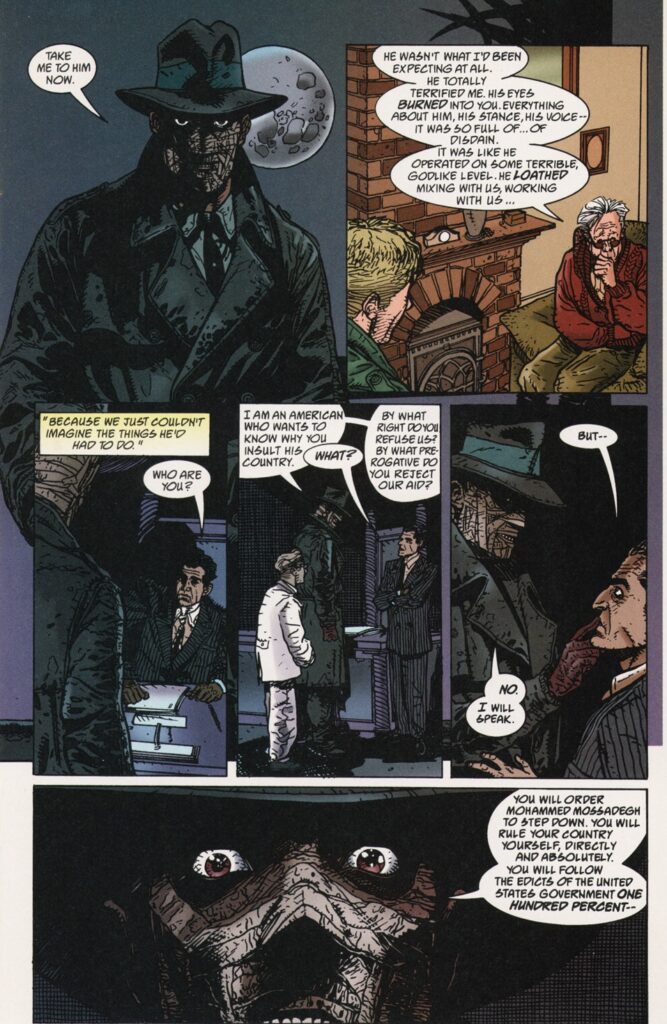

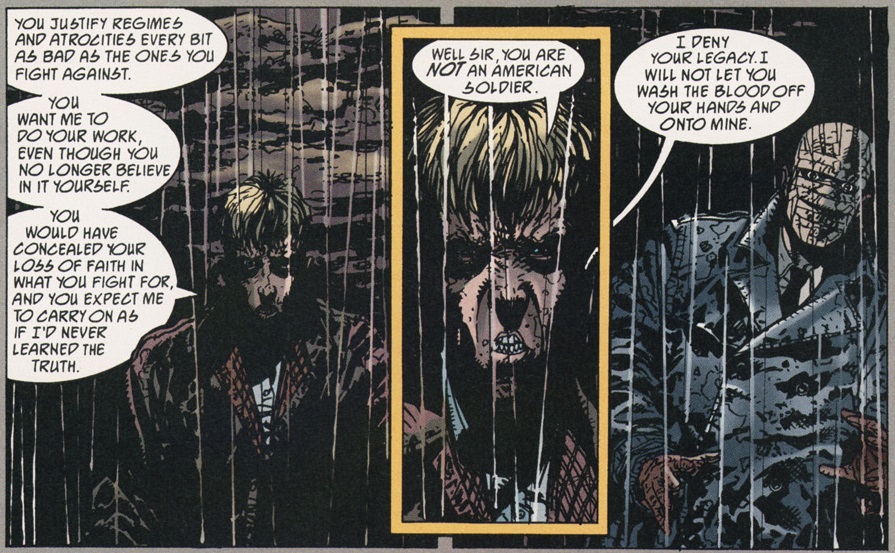

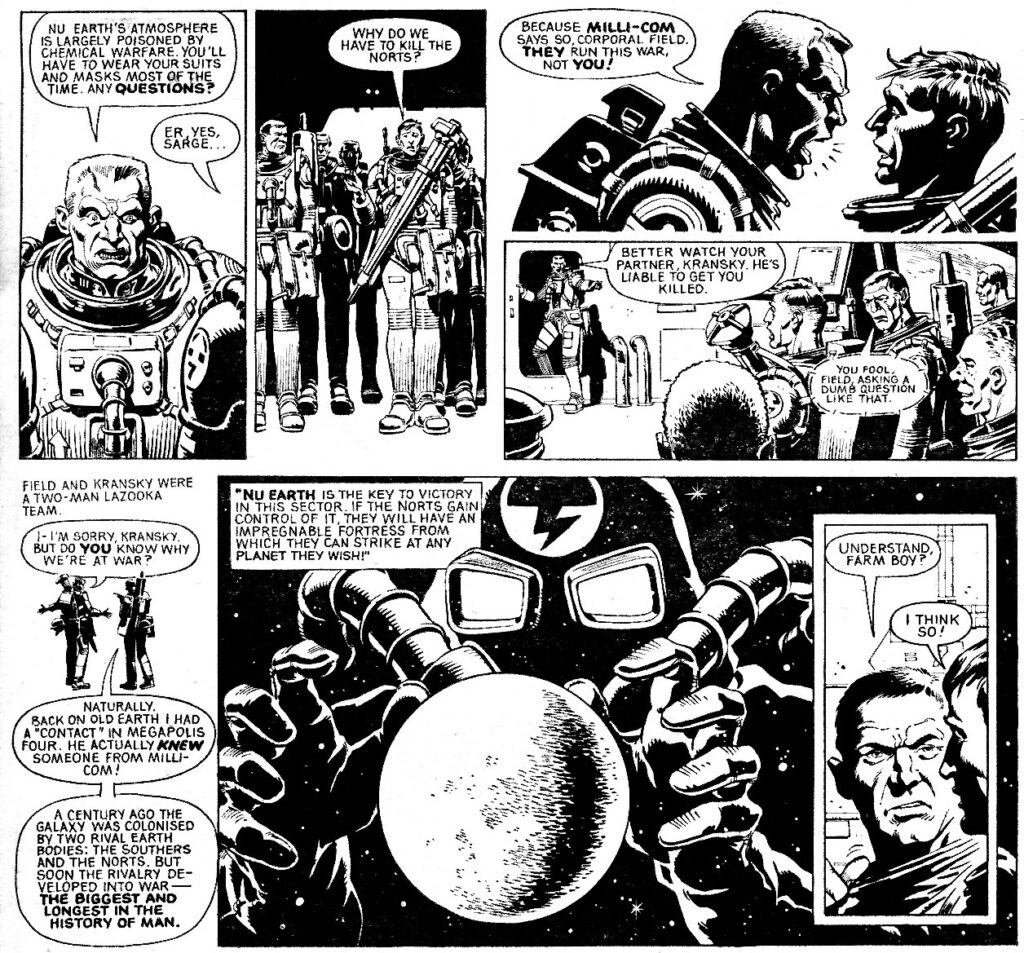

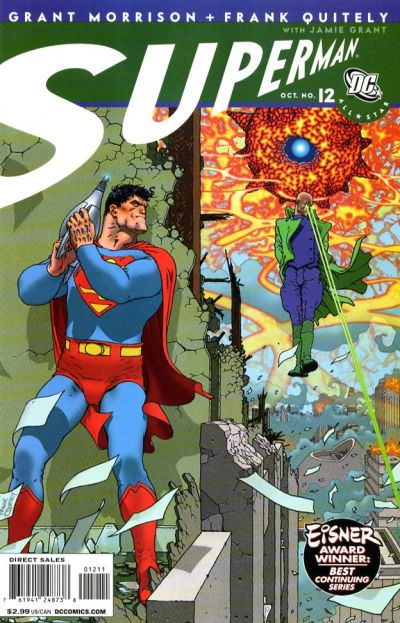

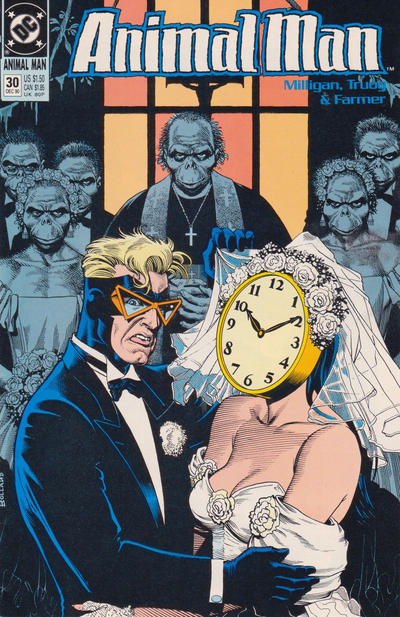

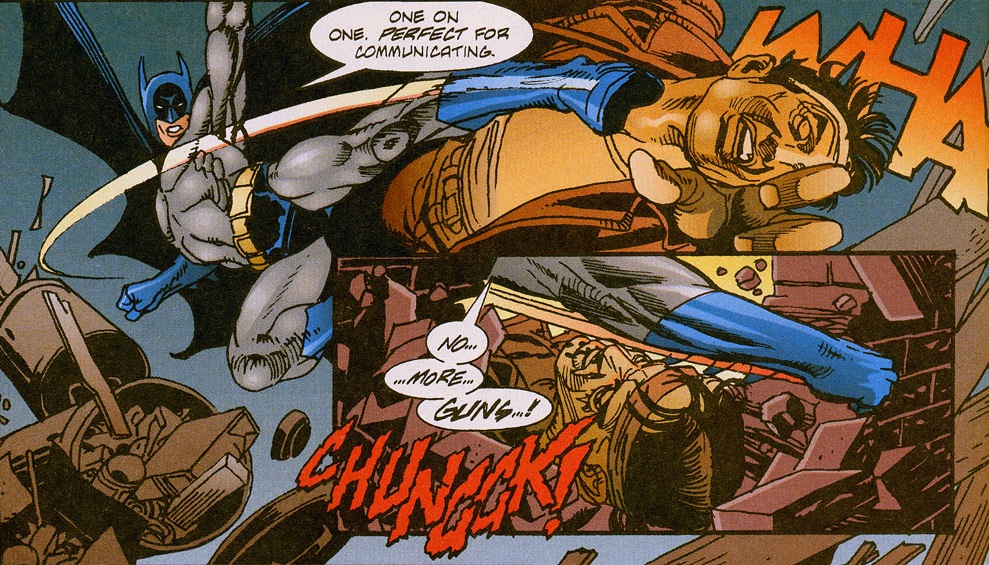

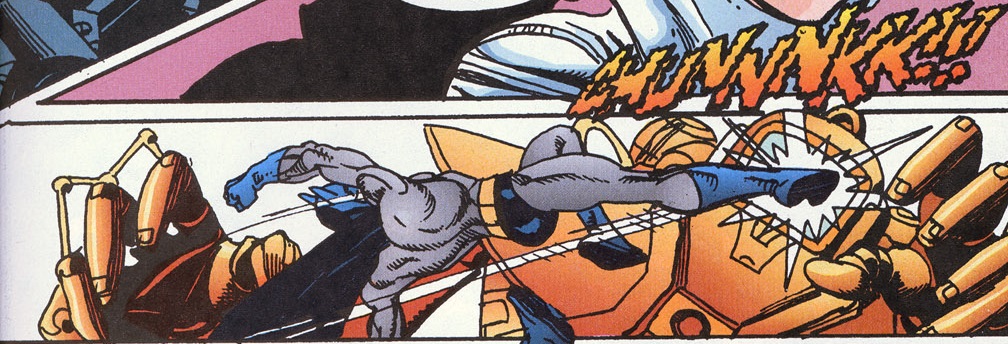

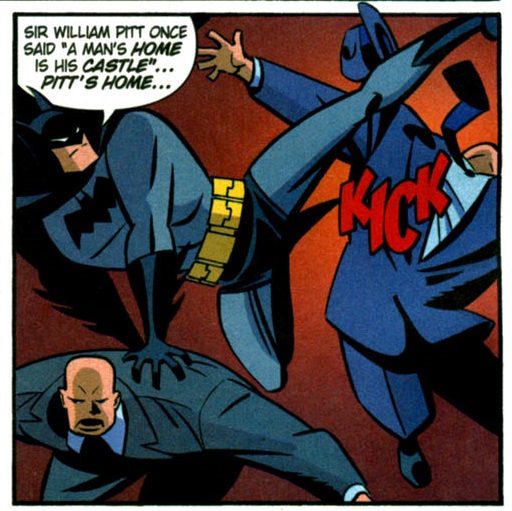

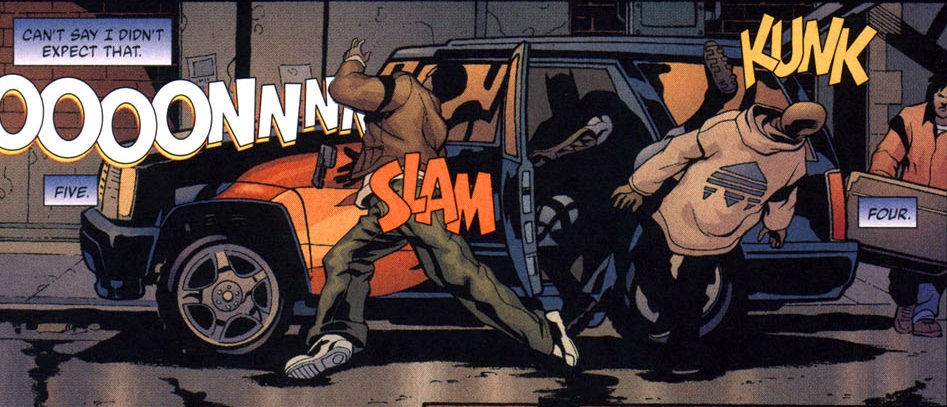

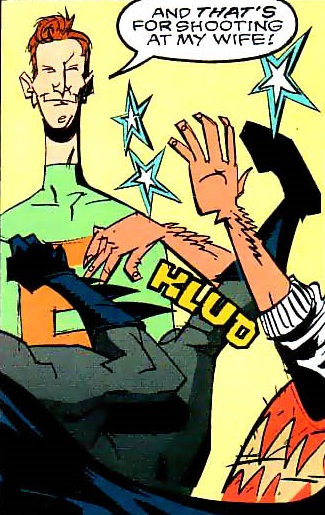

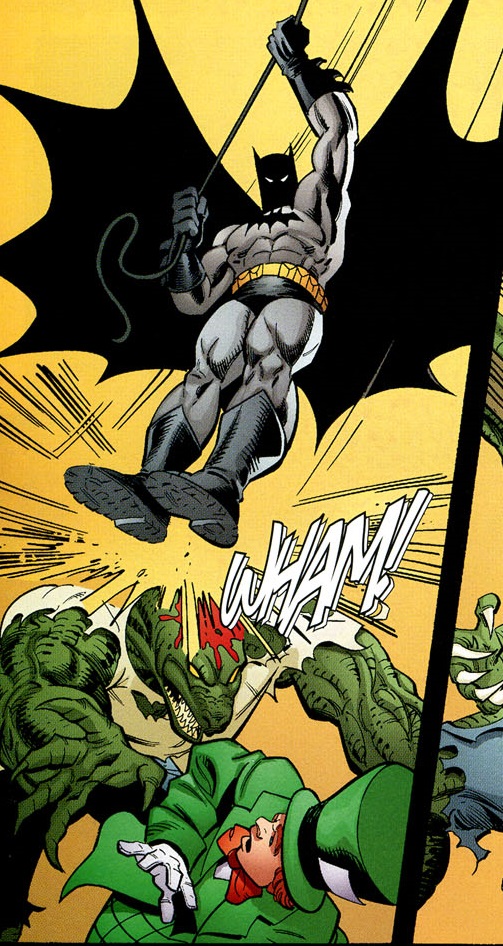

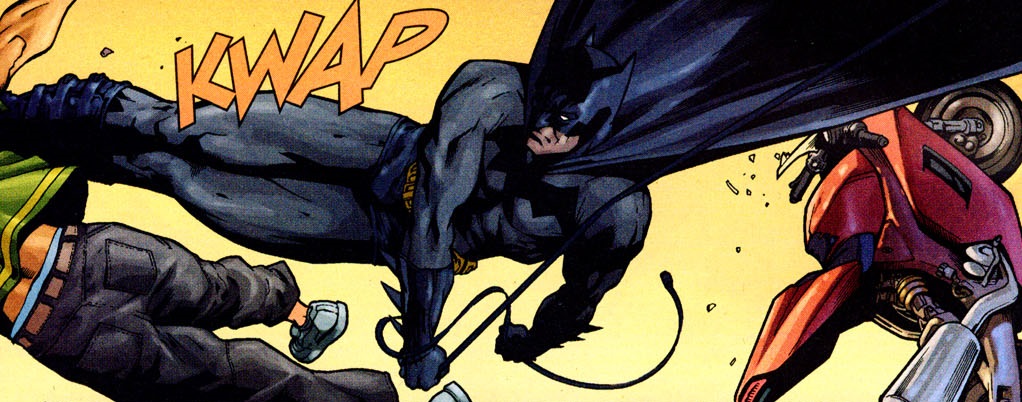

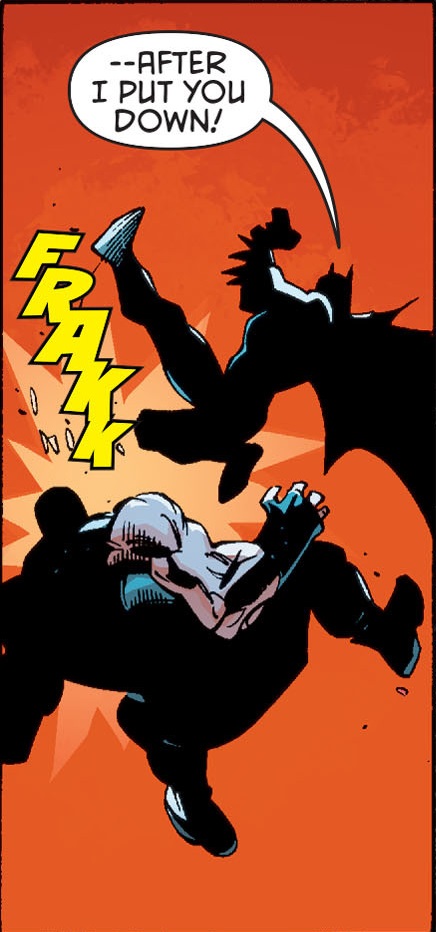

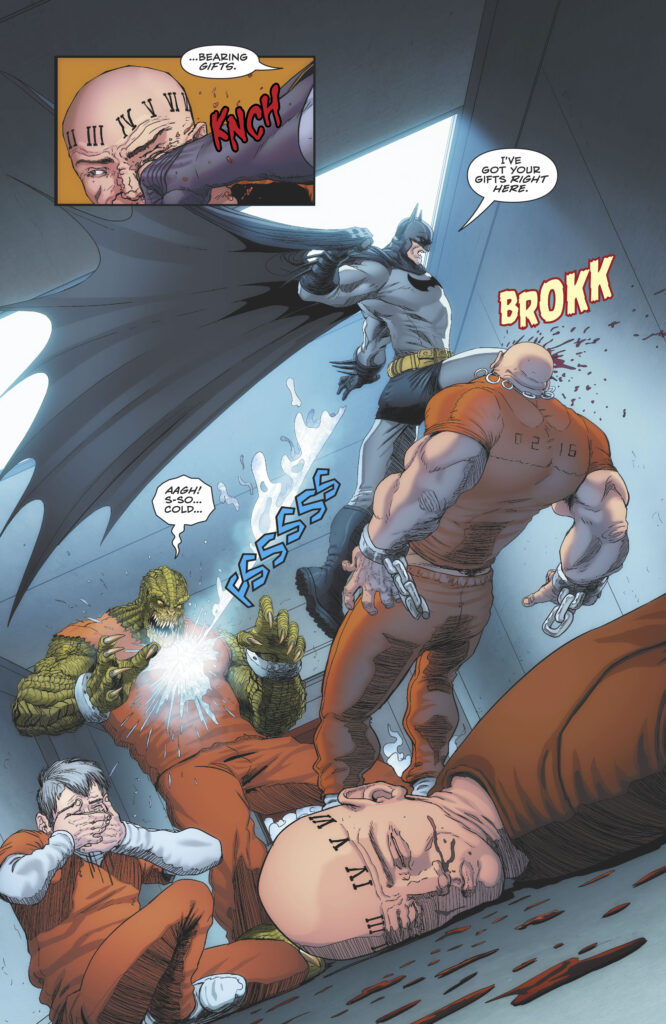

A paranoid ride through the eyes of a methodical, globetrotting, and seemingly heartless hitman, The Killer feels very much like a modern take on the sort of quasi-existentialist, process-heavy thrillers Jean-Pierre Melville used to do, with David Fincher’s ultra-immersive style more than making up for the story’s shallowness. Sure, the film is admittedly based on Matz’s and Luc Jacamon’s cool graphic novels, but those owe quite a debt to Melville themselves, so it all circles back. Michael Fassbinder’s faux philosophical voice-over is annoying at first, but once you accept it as a self-justification/self-reminder mantra to help him stay focused, it actually adds to the film’s intensity, not because of the bullshit words themselves but because they keep suggesting varying degrees of commitment. Plus, there’s the best fight scene onscreen since Atomic Blonde (which is also based on a great comic, albeit much, much less faithful to the source material…).

KIMI

(Steven Soderbergh, 2022)

A woman whose job is to review errors from an Alexa-like device suspects she may have come across the recording of a violent crime – and dealing with this involves facing both challenges and opportunities related to hyper-surveillance and to isolated work from home. Director Steven Soderbergh, who enjoys doing straight-up filmic pastiches every once in a while, here riffs on Alfred Hitchcock and Brian De Palma, brazenly deploying their cinematic style and psychological gimmicks in the world of covid-19 and #metoo. Kimi was one of the first movies to acknowledge the new realities of the pandemic era without directly commenting upon them or feeling the need to place them at the centre of the narrative. (That said, the very final shot, wrapping up the protagonist’s arc in a neat bow, is both needless and kind of annoying.)

PIG

(Michael Sarnoski, 2021)

A hermit’s truffle-sniffing pig gets brutally snatched away from him, forcing him to come out of the wilderness in search for his companion among Portland’s restaurant scene – which turns out to be eerily akin to a gangster underworld. All this may sound a bit goofy (unless you consider that most food in restaurants and markets is indeed produced/acquired through criminally inhumane means), so it’s a testament to Nicholas Cage’s intensity and to writer-director Michael Sarnoski that there is genuine tension and surprising emotion throughout the movie, leaving first-time viewers on the edge of their seats over the direction things can take at any moment. Critics presented this as John-Wick-with-a-pig-instead-of-a-dog, but that doesn’t do it justice… If you’re looking for points of reference, the result is more of a mix between Better Call Saul’s looming threats under the guise of mundane businesses and Kelley Reichardt’s powerful sense of restraint.

SILENT NIGHT

(John Woo, 2023)

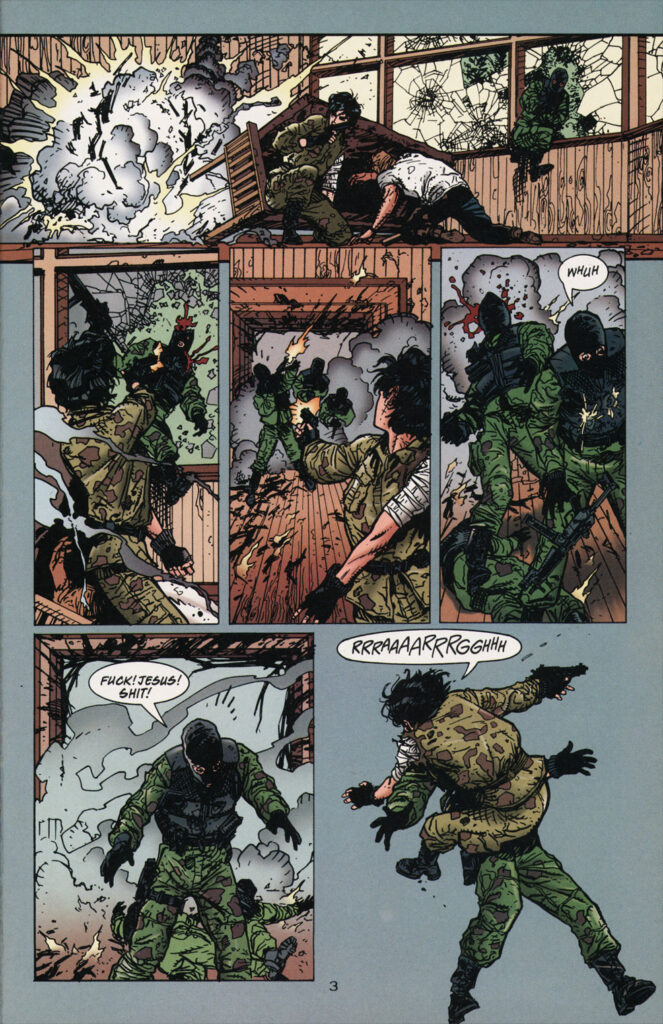

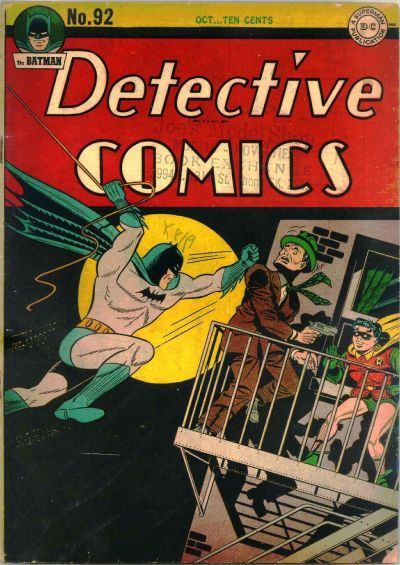

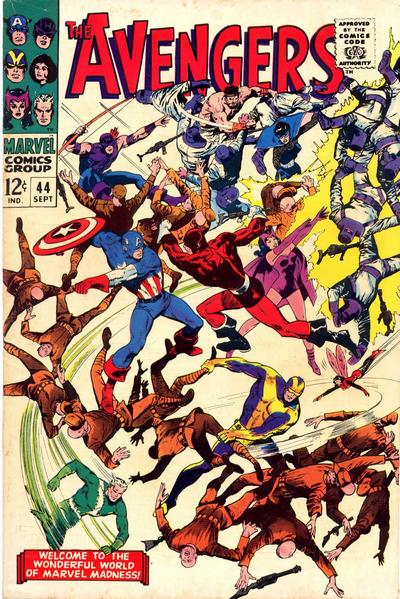

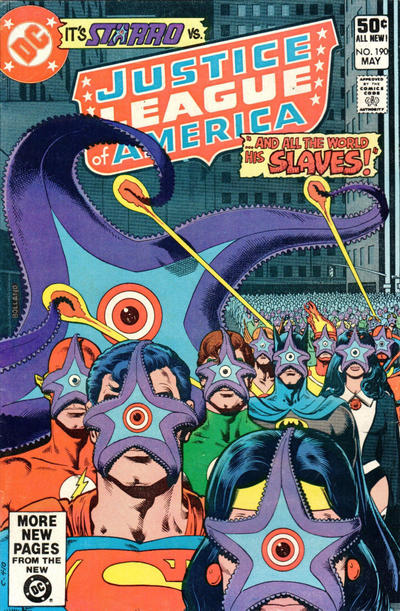

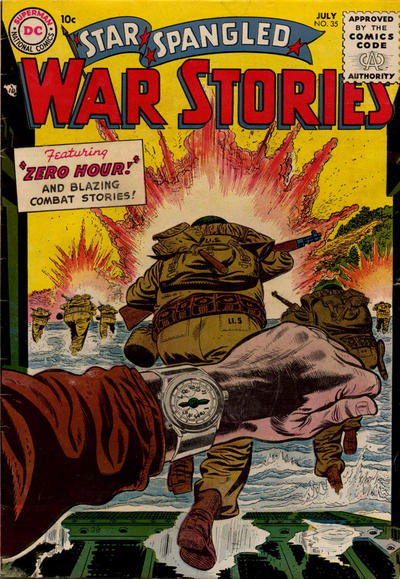

John Woo’s return to Hollywood was as safe in terms of story as it was ballsy in terms of storytelling. The former consists of a by-the-numbers revenge/vigilante justice yarn, with stock characters inexorably moving towards a bloodbath full of explosions, car fights, and gun fu. Yet the twist is that the movie is practically dialogue-free, focusing on physical action both to exhilarate and to communicate whatever is not being said (plot-relevant information, people’s motivations…). This means trimming the fat, but also making the most out of visual invention. Although it looks like one of those ‘Nuff Said issues Marvel used to put out, the result is a virtuoso act that transcends a mere gimmick, creating its own experience, so that, after a while, you stop expecting anyone to talk, as if *that* would sound artificial. To pull this off, Silent Night uses every trick in the book: while the chases and carnage are shot through Woo-esque slow motion and dazzling camera choreography, there are training montages (remember those?) as well as slapstick and melodrama set pieces that draw on techniques from silent cinema, albeit complemented by the sharpest of sound designs.