Peter Milligan has written some of my all-time favorite comic series, including the surrealist fantasy Shade, the Changing Man, the existential crime thriller Human Target, and the superhero pop satire X-Statix. However, as even his biggest fans will point out, the quality of his output is highly inconsistent… At his worst, Milligan has churned out notoriously lame work (like his infamous run on Elektra), but that’s a small price to pay for his genius. After all, when he’s on fire he can deliver densely multilayered, mind-blowing masterpieces that stand side by side with those of other acclaimed authors of the early British invasion. Seriously, Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, and Neil Gaiman would have been proud to create comics as witty and original as Enigma, Skreemer, or Rogan Gosh!

From a thematic perspective, Peter Milligan is actually quite reliable, as practically all of his books are about identity crises in one way or another – sexual identity, national identity, religious identity, etc. With a droll, insightful writing style, Milligan has found several imaginative ways of exploring this issue, making him a spiritual descendant of Italo Calvino and a precursor of Charlie Kaufman, albeit with the puckish Britishness of Douglas Adams’ Dirk Gently books. His dialogue is also very characteristic, with people talking in either dry quips (‘All we have, all we are, are clichés.’) or amusingly unrealistic outbursts of sincerity (‘Even when I’m about to die I like to sound interesting and special.’). And even though he has been at it for almost four decades, Milligan hasn’t lost his touch, as seen recently in the sadly truncated New Romancer, an entertaining sci-fi farce featuring Lord Byron in Silicon Valley.

So how to explain such a wildly inconsistent range of quality? Sometimes I wonder if it’s a matter of Peter Milligan not settling for his corner of cult fandom and therefore occasionally sacrificing what makes him special in order to seek mainstream appeal. For example, after writing a smart, funny take on Punisher comics with Wolverine/Punisher, Milligan awkwardly tried to nail the testosterone wish-fulfilment angle in that Happy Ending special a few years ago, with awful results. Then again, perhaps he was just feeling uninspired that day. Or it might have been an attempt at irony.

Surely a lot of this comes down to the fact that Milligan finds some projects artistically stimulating and takes on other assignments with a more mercenary attitude (hell, he also did a by-the-numbers adaptation of Jonathan Hensleigh’s Punisher movie). Writers like Warren Ellis or Brian K. Vaughan have pulled off the whole gun-for-hire thing while mostly retaining their authorial voices, but with Peter Milligan you never know whether or not his quirkiness is going to shine through. Fortunately, it normally does in Milligan’s forays into Gotham City… Although he clearly didn’t put as much soul and creativity into his Batman comics as he did into his masterworks, many of them are nevertheless quite fun and interesting!

That said, you probably wouldn’t guess it just based on the pretty yet generic covers:

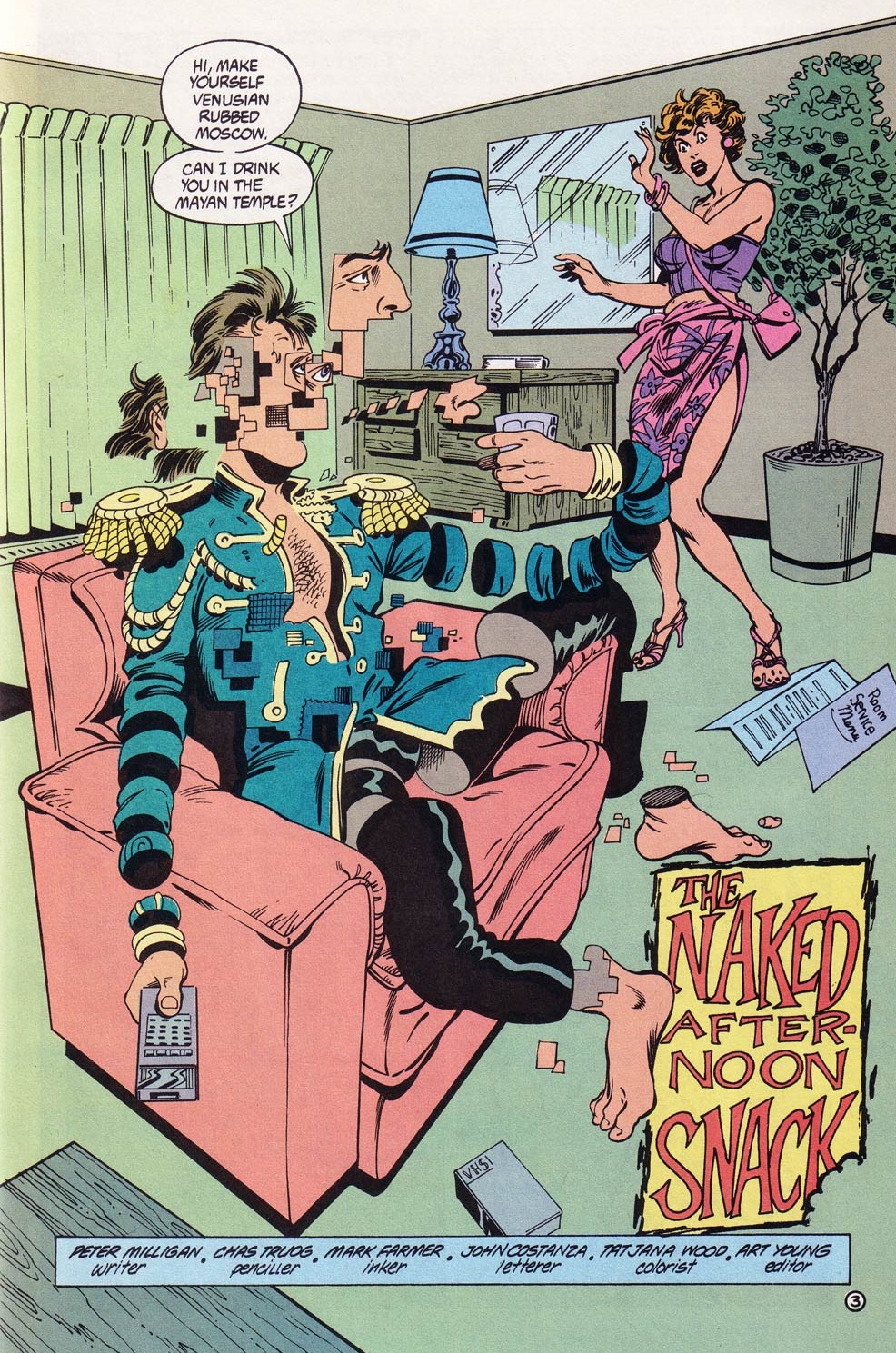

Alongside his labyrinthine plotting, eccentric characterization, and postmodern sensibility, one of Milligan’s most distinctive trademarks is his gift for the alluringly bizarre. You can definitely find the latter in his Animal Man comics, which had the thankless job of following Grant Morrison’s groundbreaking run on the title – a run that had finished with Animal Man meeting Morrison and realizing his condition as a fictional character! Milligan’s strategy for dealing with this narrative dead-end was to take the series’ hero into further strange adventures, as Animal Man woke up from a coma in a parallel world where he had to protect the US President from three psychic eight-year-old triplets.

Batman had a small cameo in that story: at one point, the Dark Knight tried to face the evil triplets, but they put him six weeks in traction. So, as an alternative, Animal Man teamed up with Nowhere Man, a molecularly displaced CIA agent who mixed segments of William Burroughs’ writings into casual conversations:

Animal Man #28

Animal Man #28

To a lesser degree, Peter Milligan’s earlier full-on Batman stuff – namely the ‘Dark Knight, Dark City’ story-arc in 1990 (Batman #452-454) and his run in Detective Comics the following year – also displayed this penchant for weirdness.

It is there from the start: in the first issue of Milligan’s run – the brilliant ‘The Hungry Grass’ (Detective Comics #629) – a criminal holds Gotham City for ransom with the help of a magical grass, only instead of money he demands that all citizens wear shirts inside out and blue mascara, that they say ‘Frank Sinatra sucks’ every ten minutes, and that they carry around pornographic books! (To be fair, given their history, Batman comics can withstand this level of surrealism better than many other superhero titles.)

Peter Milligan is usually paired with vibrant artists that keep up with his wild imagination (this is taken to a psychedelic extreme in his various collaborations with Brendan McCarthy). However, his initial issues of Detective Comics were illustrated by Jim Aparo, who had an old-school figurative style. Aparo’s deadpan approach created quite a curious – and sometimes creepy – contrast with Milligan’s odd little touches, like when the Caped Crusader fought a couple of sociopathic, multiracial conjoined twin hitmen called Two Tone:

Detective Comics #630

Detective Comics #630

Jim Aparo’s art also evoked the Bronze Age of Batman comics, in the 1970s, when Aparo had drawn a ton of similarly outlandish tales written by Bob Haney, for the long-running series The Brave and the Bold.

This Bronze Age vibe was appropriate, since Peter Milligan wrote a fairly classical take on the Caped Crusader, uncontaminated by the trend towards depicting Batman as a dark, brooding psycho in the aftermath of Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns and Tim Burton’s 1989 mega-blockbuster. Milligan’s Batman was certainly not trying to pass off as a mysterious urban legend (in fact, in Detective Comics #629 he even spoke on CBS News).

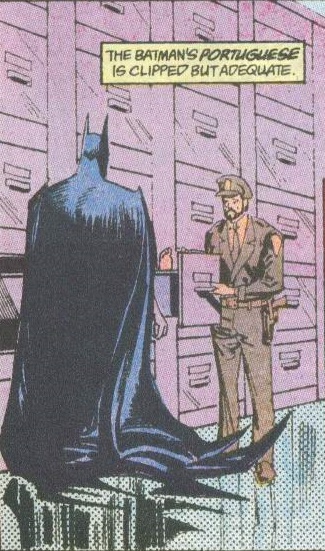

Moreover, over the years Milligan has joyfully played along with the notion that Batman is the World’s Greatest Detective and basically a Renaissance Man, or at the very least a versatile polyglot:

Batman #472

Batman #472

Batman Confidential #32

Batman Confidential #32

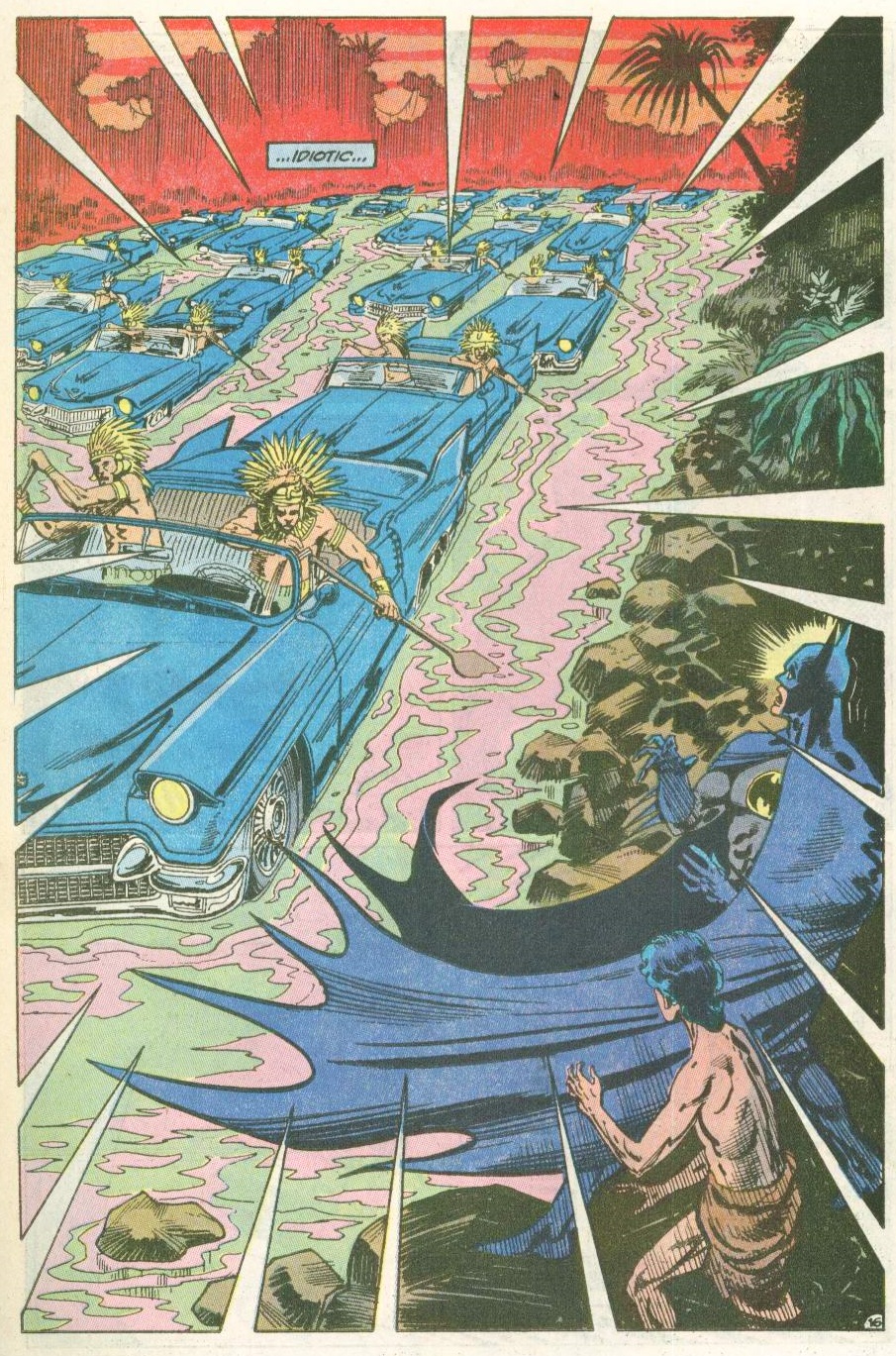

The relatively grounded, cavalier, and cerebral version of the Caped Crusader was ideal for the type of supernatural and/or psychological challenges Peter Milligan prepared for Batman. That said, the only time Milligan fully unleashed his brand of madness was in the mini-crossover ‘The Idiot’ (Batman #472-473, Detective Comics #639-640).

In this nightmarish saga, the hidden subconscious of four mental patients, bound together after consuming an Amazonian root, telepathically conjures a fifth personality – the titular Idiot, who tries to become more real by going on a mind-sucking rampage in Rio de Janeiro (and you thought things were bad enough in the lead-up to this year’s Olympics). In order to fight the villain on his terms, Batman eats some hallucinogenic root himself and enters the so-called Idiot Zone, with predictably trippy results:

Batman #473

Batman #473

More recently, Batman made a couple of brief appearances in Justice League Dark, where Peter Milligan once again sought to work his typically twisted ideas into a recognizable superhero narrative. This was an OK series about a team of idiosyncratic heroes, but it suffered from too many characters and it didn’t live up to its initial promise of unhinged strangeness (in a single page of the first issue, a shower of books killed six people, cows gave birth to mechanical meat-slicers, and a power station was suddenly imbued with consciousness).

Still, it was worth it for moments like John Constantine’s entrance into a devastated Gotham City:

Justice League Dark #7

Justice League Dark #7

I’ve stressed Peter Milligan’s knack for creating surreal, dream-like visions, but it would be unfair to imply that he is purely into bizarreness for bizarreness’ sake. In many of his best works, Milligan uses absurd fantasy or magical realism as a thought-provoking way to engage with his pet theme of identity crisis. For example, he did this in the wonderful – and shamefully overlooked – Vertigo mini-series Girl, London, and Egypt (he also did it, less successfully, in Terminal Hero and The Programme).

His Batman work is no exception. For christsake, one of Milligan’s stories is actually called ‘Identity Crisis’ (Detective Comics #633)! It’s the one where Bruce Wayne wakes up and finds out that the Batcave is no longer there and that he has never been Batman after all. When he realizes someone else is kicking butt as the Dark Knight, Bruce starts to wonder what being Batman even means at the end of the day… And yes, it’s the same premise as in the episode ‘Perchance to Dream’ from the Animated Series, but the final twist is much more of a mindfuck here. (Officially, the comic was an inspiration rather than the main basis for that episode, whose story is credited to Laren Bright and Michael Reaves. The final teleplay was by Joe R. Lansdale, who – it’s always worth remembering – besides having written his share of Batman prose short stories and novels, is also responsible for a novella about Elvis and a black JFK fighting a mummy.)

Peter Milligan even managed to shove the whole identity motif into the 2007 crossover The Resurrection of Ra’s al Ghul, a mindless adventure with all the manic energy and tongue-in-cheek orientalism of Carpenter’s Big Trouble in Little China. After co-writing the main story with Grant Morrison, Fabien Nicieza, and Paul Dini, Milligan did an epilogue called ‘The Suit of Sorrows’ (Detective Comics #842) about a suit that brought up the most violent instincts in those who wore it, forcing Batman to confront his own dark impulses.

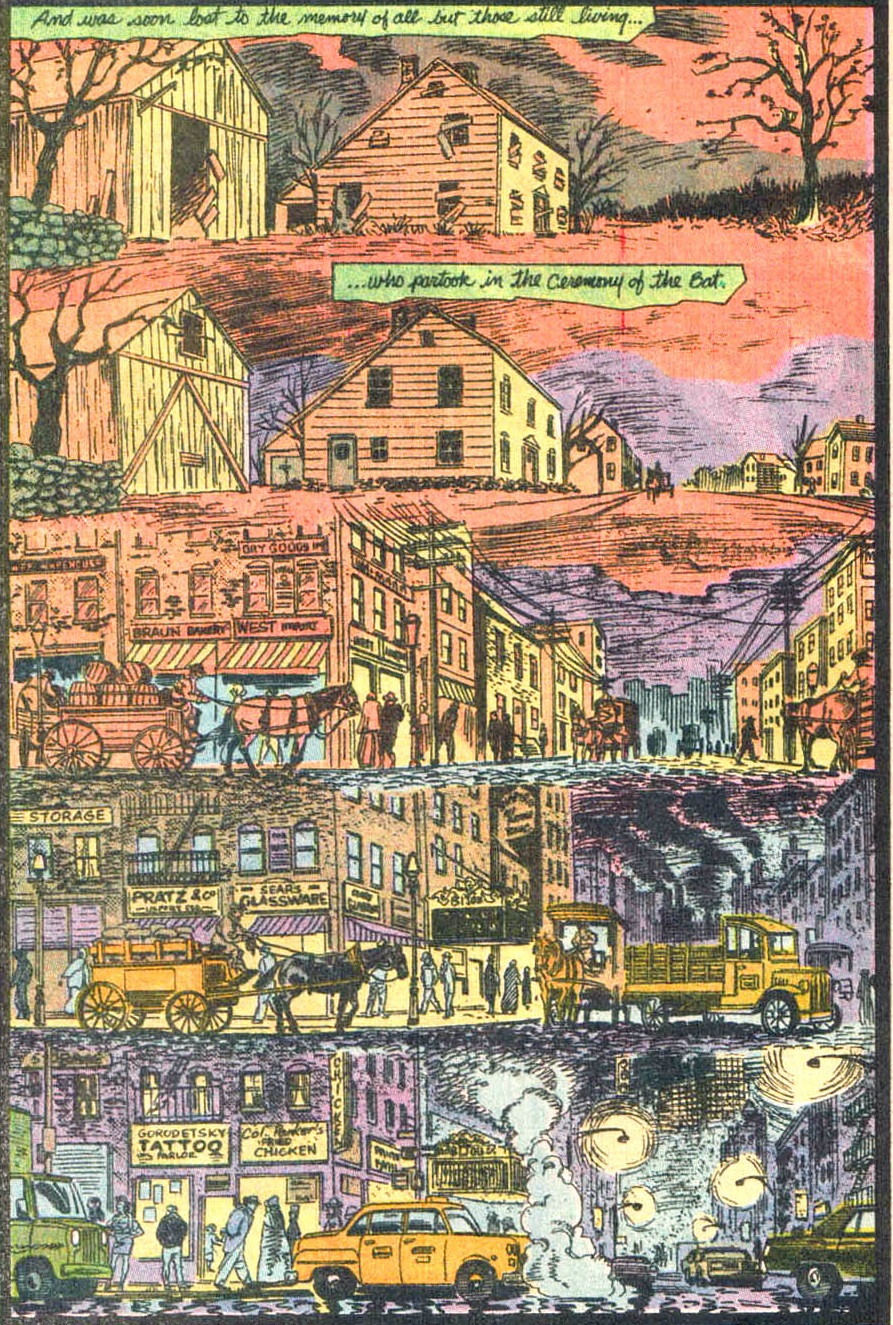

The most memorable meditation on this topic, however, takes place in ‘Dark Knight, Dark City.’ This story-arc suggests that Gotham was modeled by the demon Barbatos, who was trapped underneath the city after an aborted ritual sacrifice in 1765 (in which one of the participants was Thomas Jefferson).

Batman #453

Batman #453

The notion of Gotham being *literally* demonic would show up time and time again – Garth Ennis played with it in The Demon, Grant Morrison revisited it in The Return of Bruce Wayne (once again linked to Barbatos). Yet ‘Dark Knight, Dark City’ also explores what this means for Batman, since his origin and personality have themselves been shaped by the city… The story culminates with Bruce, near the tombs of his parents, having the following internal monologue about determinism:

‘Gotham shaped me, in that it was on Gotham’s streets that you were killed… But was it the city or the demon? Accident or design? Environment? Zeitgeist? Biology? Demons?

I shake my head, breathe deeply, try to forget it. You’re born, and your history, your time, your place, is a mold into which you’re thrown… Does it make any difference if a few demons are behind it also? My parents are still just as dead. Gotham is still Gotham.

I am still… still whatever I am…’

Peter Milligan’s existentialist musings were not limited to Batman himself, but to those around him. The sadly forgotten graphic novel Catwoman: Defiant featured a villain called Mister Handsome, obsessed with destroying beauty, in a clever tale about the significance of beauty in defining a person (for others as well as for oneself). In the New Year’s Evil one-shot ‘Mistress of Fear’ – which, like many of Milligan’s coolest comics, had lively art by Duncan Fegredo – the Scarecrow went after a girl who had been bullied, like him, but who refused to let it define her in the same way that he did. In ‘The Golem of Gotham’ (Detective Comics #631-632), Batman found himself between a Holocaust survivor and a gang of white supremacist kids – and, as usual, Milligan supplied plenty of twists, with each side’s motivations being less clear than what at first seemed. (It would be silly to compare ‘The Golem of Gotham’ to powerful graphic novels about the memory of the Holocaust like Art Spiegelman’s Maus or Rutu Modan’s The Property, but at the very least it reminds me of a biting issue of Martin Pasko’s and Rick Burchett’s pulpy Blackhawk run, called ‘The Needle Hand’).

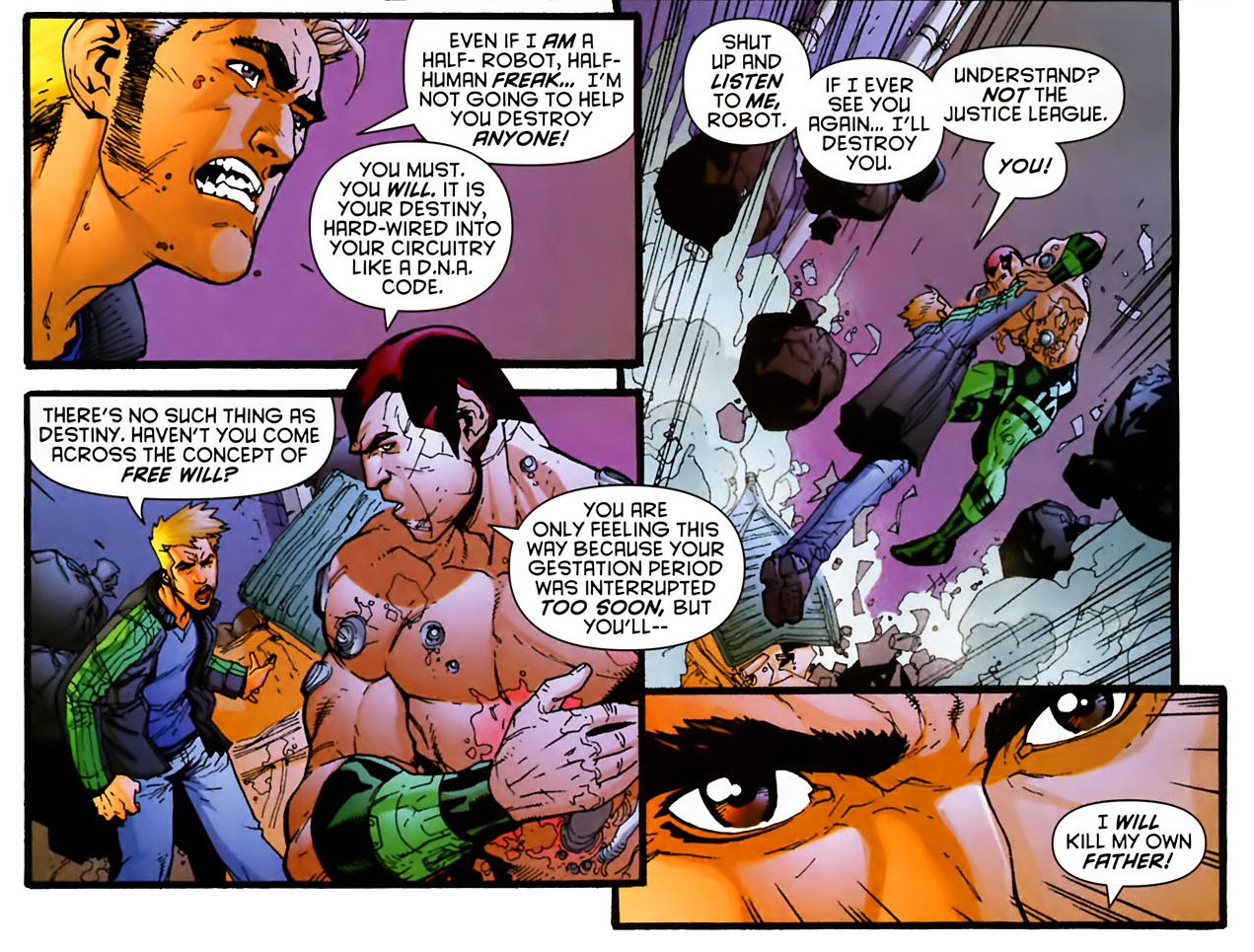

Furthermore, in the terrific story-arc ‘Kid Amazo’ (JLA Classified #37-41), Frank Halloran, a philosophy student at Berkeley, had the mother of all identity crises when he found out that he was a cyborg programmed by the supervillain Amazo to destroy the Justice League of America.

JLA Classified #37

JLA Classified #37

Leave it to Peter Milligan to pepper superhero slugfests with discussions about Nietzsche and Oedipus complex… In a neat turn, Frank’s inner conflict fed into the Justice League’s own internal crisis, as there was much arguing over whether to give Frank a chance to assert his human side or to just assume that his evil robotic legacy would inevitably take over. (Milligan’s humanist Batman took the former position.) And that was before they realized that not only did Frank have all the superpowers of the JLA, he also had all of their personalities, leading to a fascinating climax!

Finally, another aspect that is often present in Peter Milligan’s most accomplished – and, ironically, most timeless – works is a direct link to their social and political zeitgeist. Shade, the Changing Man burst with the fluid fears of early ‘90s America. Human Target channeled the post-9/11 paranoia. X-Statix captured reality TV culture and the cult of celebrity that enveloped everything from Princess Diana to Élian González. Milligan’s run on Hellblazer explored the contradictions of British history and society.

It is tempting to say that this dimension isn’t as prominent in Milligan’s Batman comics, with a few exceptions. I guess one could argue that 1991’s ‘The Bomb’ (Detective Comics #638), in which the military bring in the Caped Crusader to help them track down an escaped human bomb, is ultimately a metaphor for the disarmament debate at the end of the Cold War… However, there are a couple of more obvious examples.

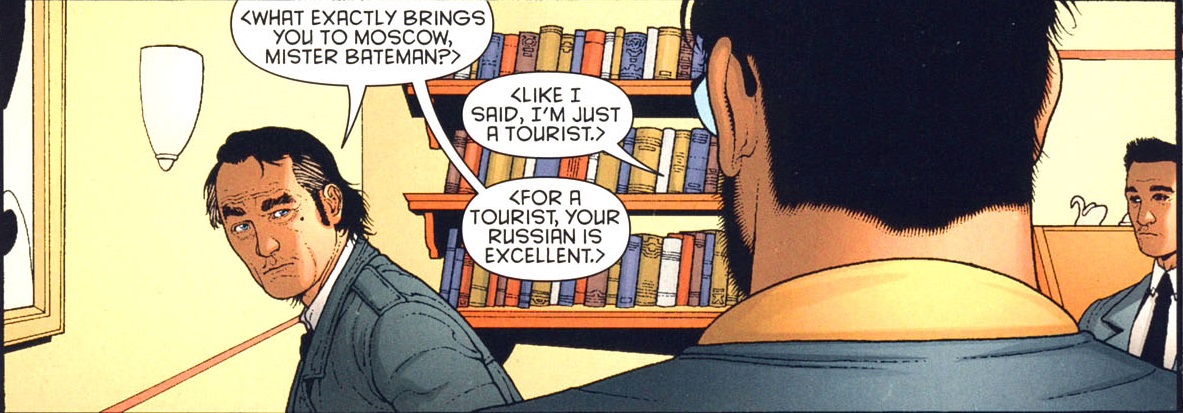

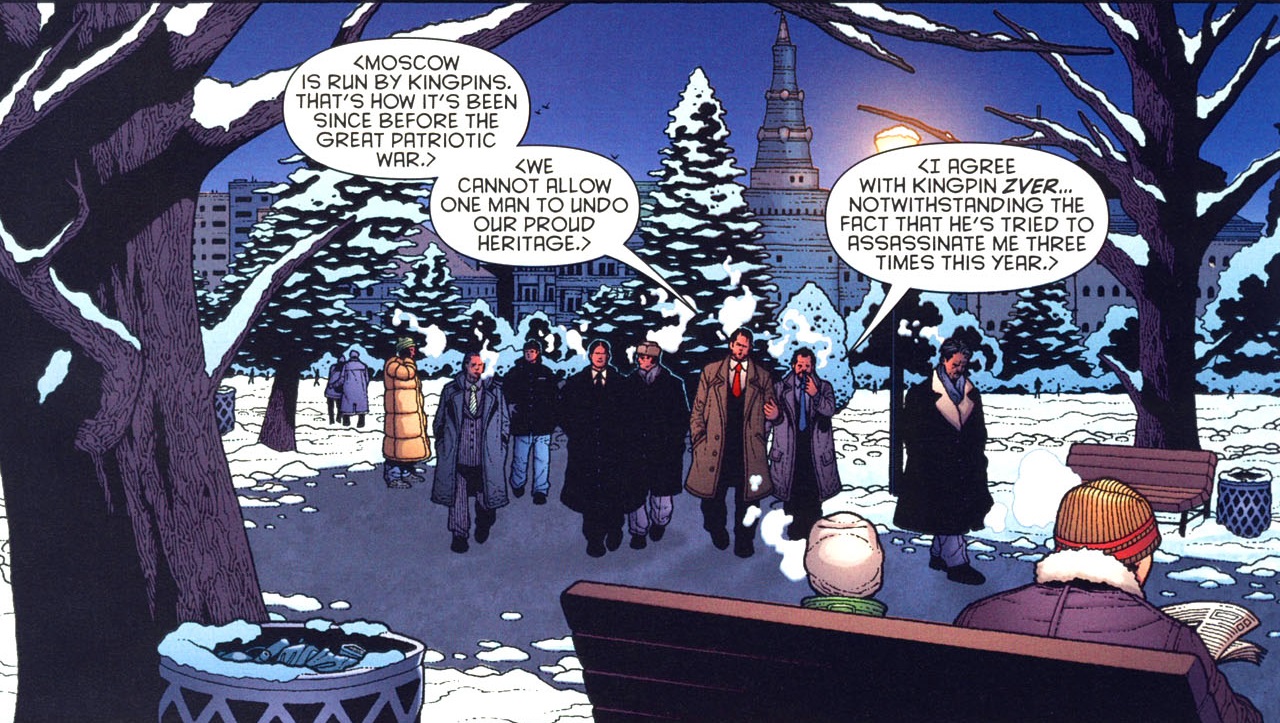

One of them is ‘The Bat and the Beast’ (Batman Confidential #31-35), in which the Dark Knight traveled to early-2000s Russia (and no, despite the title and the setting, the story didn’t feature the KGBeast). After the initial culture clash, Batman seemed to gradually realize that Moscow was not that different from Gotham City after all…

Batman Confidential #31

Batman Confidential #31

And, of course, there was 2013’s Legends of the Dark Knight arc ‘Return of Batman,’ in which we found out that Waynetech’s property portfolio was decimated by the company’s exposure to the sub-prime mortgage crisis. Hit by the economic downturn, the Caped Crusader now had to become much more cost-conscious.

Too bad that at the same time he also had to prevent Ra’s al Ghul’s latest attempt to unleash biological Armageddon upon Gotham City…

A well-thought-out and executed overview of not only Milligan’s Batman work, but I also appreciated the references to his non-Batman comics and the recurring themes found there. I found these especially useful as I am largely unfamiliar with Milligan’s work.

I read “Dark Knight, Dark City” during one of my infrequent forays into then-contemporary comics–I would always check back to see what Batman was up to–and of course I thoroughly enjoyed the best use of the Riddler yet put to paper.

I only recently picked up the rest of Milligan’s run so I cannot comment on those just yet. Part of me wonders if the magic aspects will clash with my preferred down-to-earth vision of Batman, but the other part of me says “just go with it” and enjoy.

Looking forward to your hopefully upcoming overviews on Doug Moench’s runs–particularly his 1983-86 run, which is largely overlooked.

Thanks for the kind words! I hope you enjoy Milligan’s run – I think part of the fun is precisely the contrast between Batman’s down-to-earth posture and Milligan’s brand of offbeat existentialist horror.

I’ve started working on the Moench overview, but I still have to track down a few issues. There is so much cool stuff in there, waiting to be rediscovered (I love his 80s run, but I wanted to compare it to his insane later period). Hopefully I’ll get to it before the end of the year…

Excellent article (I came here from the link in the Jim Aparo article). I agree that Milligan’s work is hit and miss. Sometimes I would read one of his stories and wonder if he was actually the same writer who gave us X-Statix and Shade, some of the greatest comics I have ever read. I will have to track down some of the newer stories you mention.