Another December, another Star Wars movie, another Gotham Calling post spotlighting sci-fi war comics…

To be honest, as far as the main Star Wars series is concerned, The Last Jedi may be the one that finally lost me. I rolled with the fact that The Force Awakens was more of a remake than a sequel because a) I could see the need to safely recapture the feel of the original movie in order to seek distance from George Lucas’ maligned prequel trilogy and b) at least the result was well-paced and fun. Yet I’m not willing to take such lack of creativity from Episode VIII, which mostly reshuffles the same limited stock of situations, settings, and character types, with little interest in exploring the untapped potential of its vast galaxy far far away.

Although I won’t join the small chorus chanting for the rehabilitation of the prequels, I’ll gladly concede that the eagerness to try out new landscapes and story ideas was one of their few redeeming features. For all the lame acting and plot holes, we still got the eerie rain-drenched planet of Kamino, the eye-popping city planet of Coruscant, the showdown at the Petranaki gladiator arena, the brutal climax by the lava river, and that crazy fight among the hovering seats of the Galactic Senate (a blatant metaphor for the destruction of democracy at a time when Bush seemed like the scariest conceivable president!). If only The Last Jedi had shared this desire to wow audiences with novelty instead of settling for the introduction of a handful of cute animals and a (poorly developed) rich version of Chalmun’s Cantina…

Sure, I liked the red visual motifs and some of the military strategy stuff and I’m certainly not adverse to a derivative component in genre fiction, but I expected Rian Johnson to bring much more style and wit to the table – if nothing else, I assumed the film might be an interesting failure rather than something this tiresome and uninspired. We are left with the same basic conflict around the same generic brand of proto-Nazi villains (though sidestepping the issue of antisemitism). Even the narrative twists and thematic shifts that have upset so many fans feel like little more than superficial variations on what came before. Hell, your average episode of Rick and Morty has more memorable sci-fi/fantasy set pieces than The Last Jedi’s 152 minutes!

In 2017 alone, Disney has proven twice that it can deliver enticing space operas full of weird worlds and aliens (namely Guardians of the Galaxy vol.2 and Thor: Ragnarok). Regardless of Episode VIII‘s awkward jokes, I suppose the idea here was to ground this franchise as a dark, self-important counterpoint to the colorful Marvel Cinematic Universe yet that’s no excuse to be so bland… Or maybe the studio actually did give Johnson more creative control than usual – in that case, it’s even more of a shame that he chose to let Star Wars remain stuck in the recycle bin.

Whether or not you share my disappointment, if you’re a fan of war-related science fiction, I’m sure you’ll have a more rewarding experience reading the following comic books:

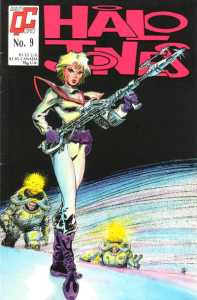

THE BALLAD OF HALO JONES

I grew up with the resourceful female leads of eighties’ sci-fi and horror – not just Princess Leia, Ellen Ripley, and Sarah Connor, but also Nancy Thompson (from A Nightmare on Elm Street) and Sarah Bowman (from Day of the Dead), among others. In comics, to a large degree this role was filled by Halo Jones, created by Alan Moore and Ian Gibson on the pages of the anthology 2000 AD, where her adventures ran from 1984 until 1986. Moore and Gibson only did three story-arcs – as opposed to the nine they had originally planned – yet there’s still a lot to enjoy here!

One of the cool things about Halo Jones is that she didn’t start off as a kickass hero – the initial point of the series was that she was an ordinary woman in an extraordinary world (i.e. in the 50th century). To quote one of the collection’s introductions, Halo Jones wasn’t meant to be either ‘a pretty scatterbrain who fainted a lot and had trouble keeping her clothes on’ or another ‘Tough Bitch With A Disintegrator And An Extra ‘Y’ Chromosome.’ In fact, she was a relatively passive protagonist most of the time, which made it even more striking when she finally took action.

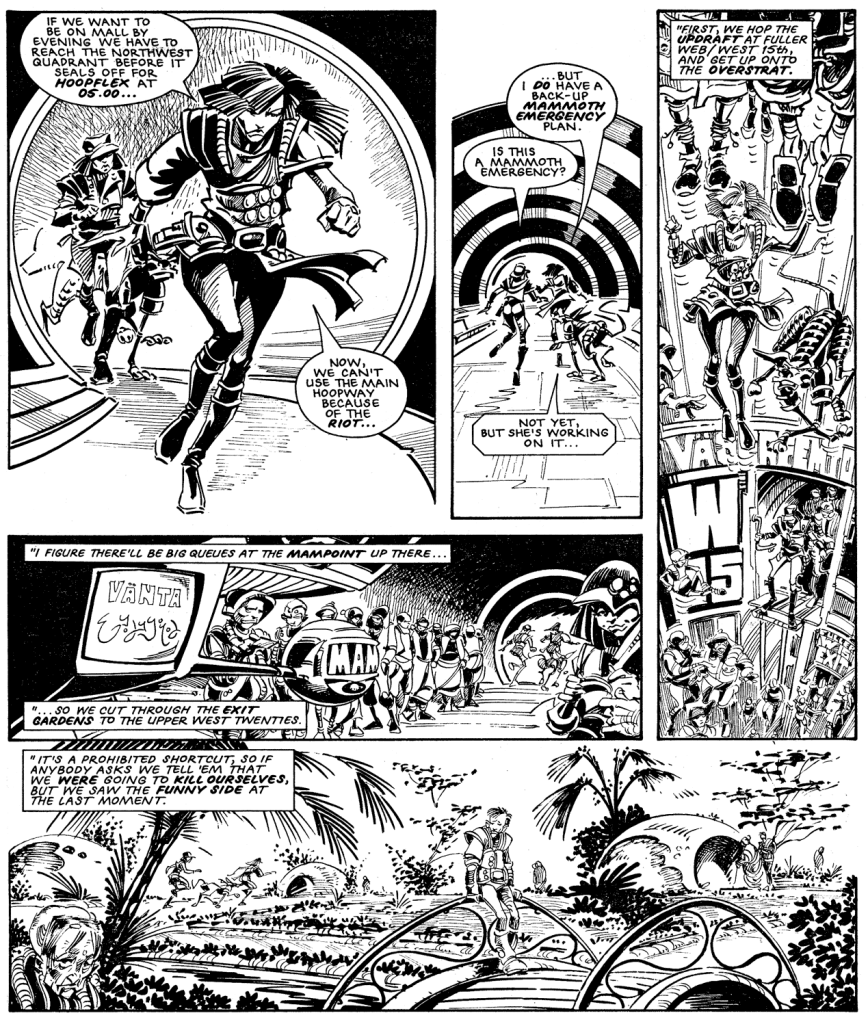

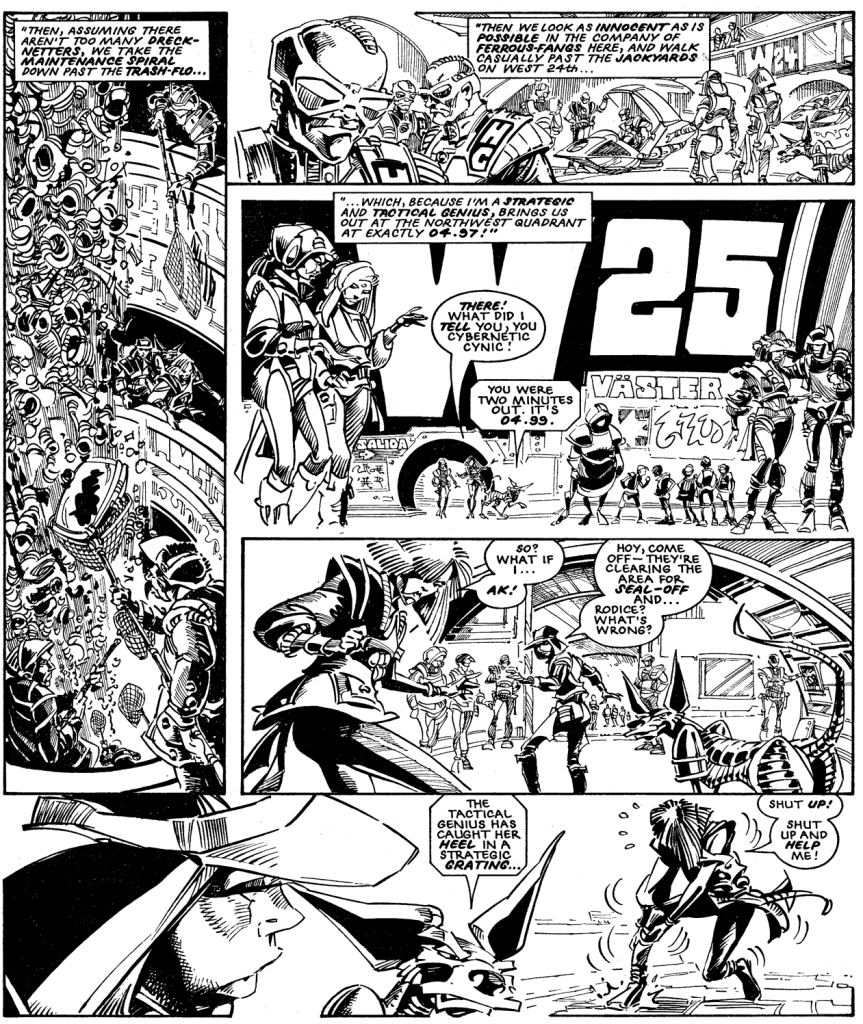

You can see this ‘everywoman’ angle not only in Halo’s characterization, but also in the kind of challenges she had to face. Early tales revolved around walking in the street at night or undertaking a shopping expedition to the mall during a riot, as well as – more generally – around Halo’s dreams of leaving her miserable, claustrophobic borough, the Hoop (technically a huge floating hoop tethered off the point of Manhattan where the Allied Municipalities of America dumped their unemployed population). Believe it or not, all this makes for a stimulating read… Having conceived Halo Jones’ world in great detail, Moore and Gibson drop us in the middle of it without much explanation, so it takes readers time to fully work out her society’s slang and inner workings. The result is sort of a futuristic take on indie comix such as the Hernandez brothers’ Love and Rockets.

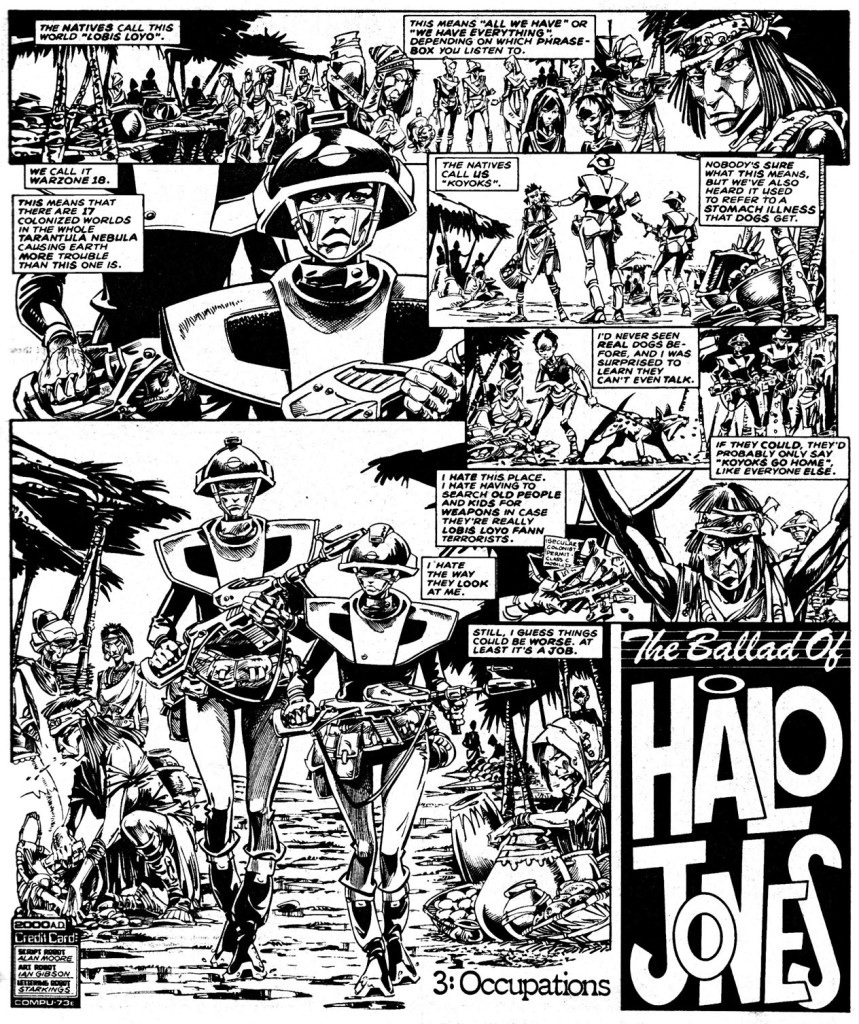

Not that there isn’t plenty of 2000 AD’s signature over-the-top social commentary. The first book – set when Halo Jones is eighteen – takes place in the Hoop, against the crime-infested background of teen gangs like the Different Drummers (a cult whose brain implants give them a persistent hypnotic drum-beat inside their heads) and racial tension between humans and the extraterrestrial migrant community. Halo’s best friend walks around armed with ‘zenades,’ which is a type of grenade that plunges its targets into a forced state of Zen meditation. In the second book, Halo becomes a hostess at a luxury liner spaceship, where she serves the privileged elites. There is a touching subplot about a transgender stowaway who has slipped beneath the threshold of human awareness and a longer storyline about a deranged robot dog. By the third book, Halo – now twenty-nine years old – finds herself in the middle of an intergalactic war in the resource-rich Tarantulan colonies:

Alan Moore has always been a master of sneaking in hidden depths and planting seeds underneath a deceptively simple surface. For example, while the square-jawed lead of Moore’s retro series Tom Strong may read like a fairly one-dimensional upbeat science hero, that comic kept hinting at the profound emotional scars from his rigid upbringing (this paid off brilliantly in the story-arc ‘How Tom Stone Got Started’). More recently, in the novel Jerusalem, a lengthy series of vignettes about working class Northampton turned out to be an intricately woven set-up for the darkly whimsical escapades of a gang of ghost kids, which in turn led to an experimental, ultra-dense exploration of large metaphysical questions.

Similarly, having established its mundane protagonist over a couple of relatively lighthearted arcs, The Ballad of Halo Jones goes on to convey the psychological damage warfare can have on a regular person. The comic uses science fiction devices to powerfully conjure up the horror and inhumanity of imperialist conflicts – most notably through the planet Moab, whose enormous gravity and time dilation effect makes it hard to distinguish between five minutes and two months. My favorite tale, though, is the one that opens with Halo stating that she just saw someone continue to age after they were dead (2000 AD #455) yet instead of providing a sci-fi explanation for this phenomenon, the story ends up delivering a devastatingly realistic payoff.

EAST OF WEST

East of West begins in the year 2064 of a counterfactual history where Native Americans joined forces to attack the Union during the Civil War, splitting the United States into seven nations. As if this wasn’t enough of a high concept, a top-secret cabal has made a pact with three of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse to manufacture the end of the world. What we end up with is a manga-style fantasy saga that doubles down as a surreal political allegory.

This is another one of those series where part of the thrill is figuring out what the hell is going on. At first, the closest thing to a hero is none other than Death himself, a literal pale rider who has fallen in love with a descendant of Mao Zedong. Yet the main cast becomes increasingly diverse as the narrative reaches for epic proportions. Each of the seven nations extrapolates elements of US history and society, from the slave-founded Kingdom of New Orleans to the shaman-ruled machine state known as the Endless Nation. What’s more, the geopolitical balance keeps shifting, as they conspire and wage war on each other, engaging in a form of supernatural game theory. We see this mostly at the elite level – even the occasional glimpses from below, like in the breakneck heist tale ‘Watch Us As We Rob Them Blind’ (issue #31), ultimately reflect the rulers’ amoral grand design, which I assume is one of the comic’s larger points.

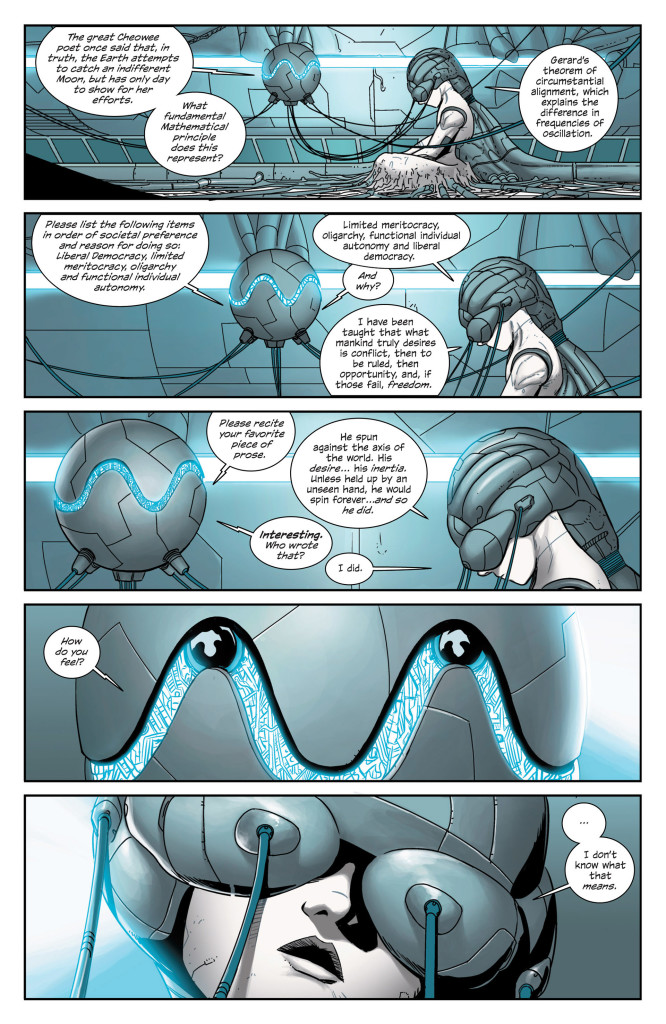

Jonathan Hickman tends to really cut loose in his creator-owned projects, writing stylish comic books that are choked with ambition, violence, and satire. This ongoing series is no exception, as he populates East of West with his bitter views on the machinations of power (‘Justice is what the strong do to the weak.’) as well as several moments of mind-bending science fiction, usually related to the subplot about a precocious little boy who may prove to be the Beast of the Apocalypse and who is being raised by a creepy AI:

It’s as if Sergio Leone was directing an anime version of Game of Thrones. Indeed, the title works both as a reference to a line in the story’s prophecy (‘Born of the East, child of the West, the one true son of America.’) and as an allusion to the series’ multiple genre influences. There are gunslingers riding fire-spewing horses under the sunset. There is a magical desert between the waking world and other realms. There is body horror and bloody action (including a silent tour-de-force in issue #22). There are dystopic cities, massive battles, and telepathic mutants. And even if you find yourself struggling to pierce through Hickman’s cryptic, hyperbolic, cool-as-fuck dialogue, the superb art should push you along, what with Nick Dragotta’s expressive, cartoony line work and Frank Martin’s vivid color choices, not to mention Rus Wooton’s stellar lettering.

IGNITION CITY

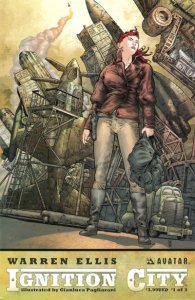

Warren Ellis can crank these babies up in his sleep. He has written plenty of smart takes on sci-fi warfare, from telling a caustic reverse-Star Trek tale of space guerrilla in Switchblade Honey to playing with manga and kaiju tropes in Tokyo Storm Warning. Hell, he even did a solid job with the Starship Troopers prequel comics! For the mini-series Ignition City, he went in a different direction, imagining a dieselpunk timeline in which pulp heroes like Flash Gordon and Dan Dare spend their lives in the titular settlement, marked by the memory of a WWII-like war in the faraway planet of Khargu.

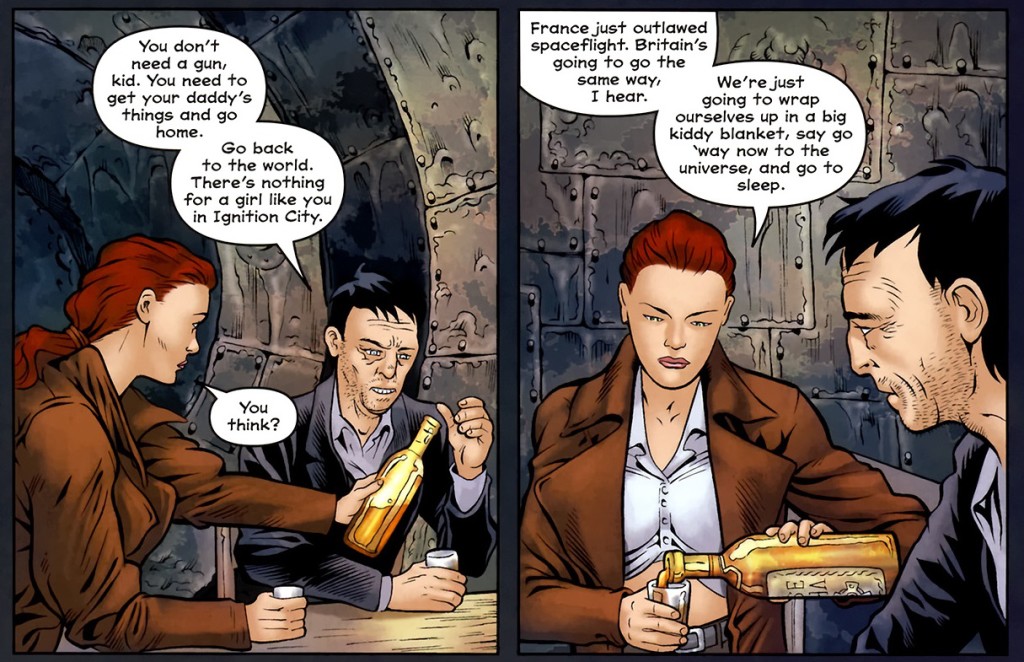

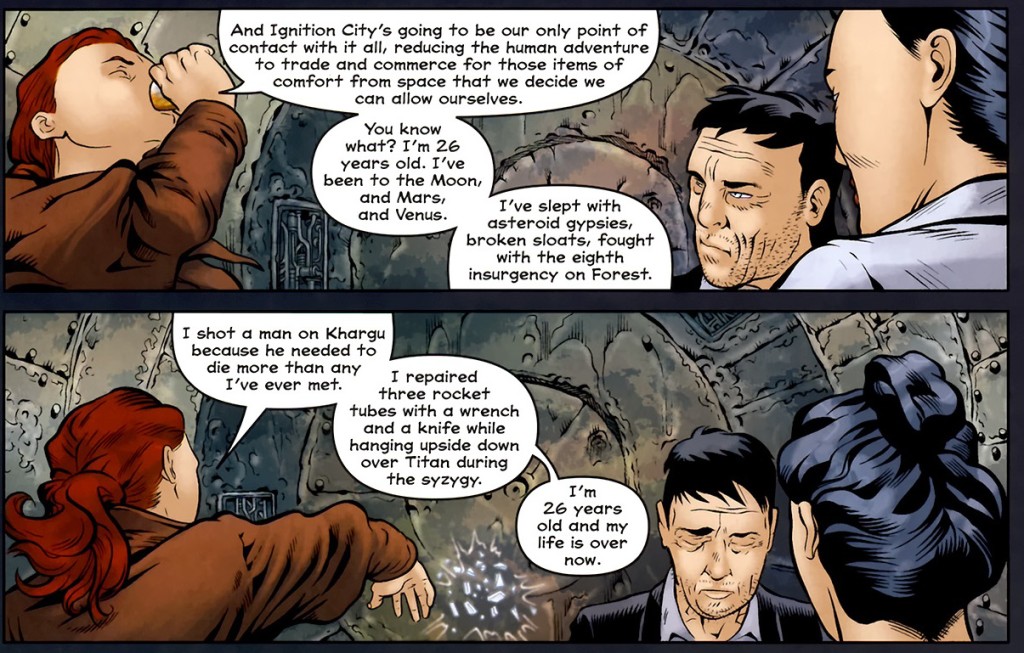

The whole thing is a masterclass of shorthand characterization and economic storytelling. Just look at the image above and see how much information the first couple of pages convey… We immediately learn that this tale is set in an odd version of 1956 in which Berlin is not a divided city, but rather a sprawling metropolis with rusty-looking flying machines. Plus, the dialogue indicates that a number of nations have already engaged in space travel, although Europe has now mostly abandoned it, except for Britain, where it is government-controlled (suggesting that in other places it was not). Moreover, we meet the series’ protagonist, Mary Raven, an emancipated woman who sounds upset at the prospect of humanity giving up on space exploration. We are thus thrown into a world that is both recognizable and markedly different from our own, a world full of questions and possibilities.

When Mary learns of the death of her father – a former intergalactic hero – she goes looking for answers in Ignition City, Earth’s last remaining spaceport (‘an artificial island on the equator, ringed by launch gantries and landing pads’). Although initially set up like a mystery, what we get is closer to a western with laser pistols, as Mary finds herself in a fucked up quasi-lawless town populated by drunken spacemen, including the Russian cosmonaut Yuri (probably a version of Yuri Gagarin) and the depressed time-traveler Bronco (a Buck Rogers stand-in). The filthy language could even be seen as a nod to Deadwood!

That said, Mary soon proves to be your typical Ellis lead, i.e. a fierce yet frustrated romantic who wants to be an explorer – not necessarily because of faith in progress per se, but because of a desire to discover new things, to see new sights, to be awed by what is out there:

To be sure, mixing westerns and space adventure is not unique. In film, the most obvious examples are the charming Battle Beyond the Stars (which reworks The Magnificent Seven in another galaxy) and the gritty Outland (whose second half features a futuristic take on High Noon). In comics, Chuck Dixon and Judith Hunt did it in Evangeline. More recently, Jay Faerber, Scott Godlewski, and Drew Moss have pulled it off beautifully in Copperhead.

What makes Ignition City so special – besides its twisted humor – is Warren Ellis’ knack for worldbuilding. Together with artist Gianluca Pagliarani, he crafted a fascinating microcosm with a lively cast, history, practical rules, architecture, and geography. Moreover, the story’s resolution compellingly resonates with real-world politics. The result may feel a bit rushed, but overall this comic is damn funny, intelligent, moving, gorgeous, and thought-provoking.

I wish I could say the same for The Last Jedi…