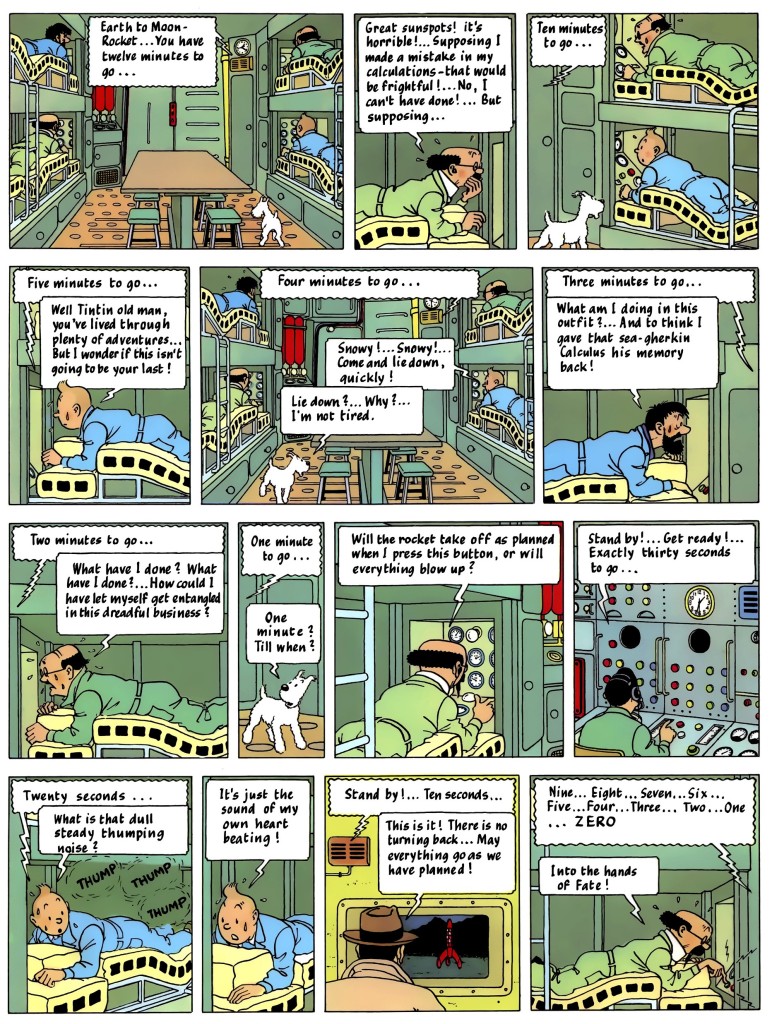

If you just look at the artwork in The Adventures of Tintin, it’s hard to deny the series’ ethnocentrism, since Hergé’s drawings – as was usual at the time – tap on recognizable stereotypes. If you look closely at the stories, though, it’s a bit more complicated. You can definitely find a humanistic strain in there, with empathy towards victims of imperialism going even as far back as Tintin in America, which, regardless of its caricatural portrayal of Native Americans earlier on, does contain this unforgettable slice of satire:

Tintin in America

Tintin in America

Captain Haddock aside, openly racist characters are villains and Tintin clearly opposes at least the most vicious forms of bigotry, even in some of the comics from the 1930s. For example, in The Blue Lotus he stands up for a rickshaw driver being verbally and physically assaulted by a western asshole and, later in the story, he befriends a local kid, Chang, by mocking all the stupid myths Europeans believe about China. Sure, even this smacks of a certain ‘white man’s burden’ protective mentality (colonial officers are often allies in the early books), to which you can add a tinge of orientalism and a ‘clash of civilizations’ vibe (as is typical of the whole genre of adventure yarns about western characters encountering danger in exotic lands), although it is worth noting that The Blue Lotus and Chang’s character in particular were inspired by Hergé’s real-life friendship with Chinese artist Zhang Chongren. And while the depiction of many of the Europeans as bumbling and/or evil may not quite make up for the fact that the characterization of non-whites often falls into tropes (sometimes played for laughs) about simple-minded or culturally baffling foreigners, I’d still stress that there is variety among those depictions, including plenty of sympathetic and dignified characters.

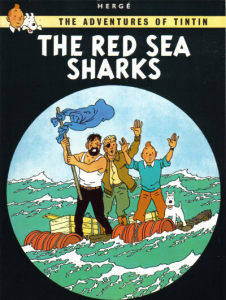

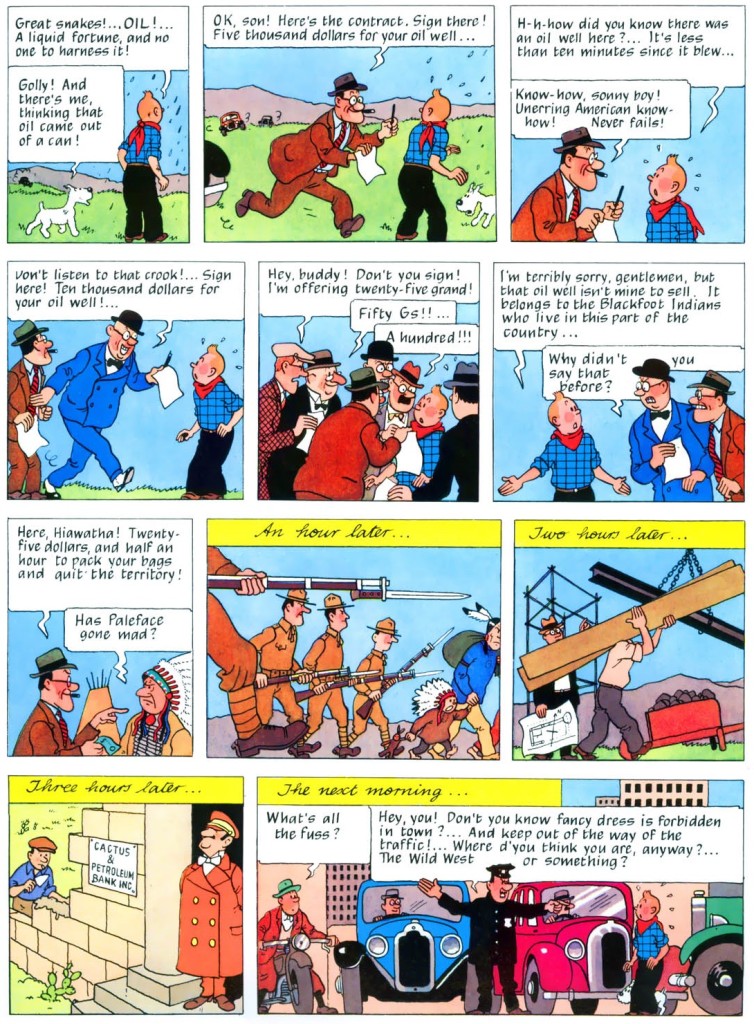

The result can be an interesting mess of progressive values and culturally insensitive choices, taken to a complex extreme in The Red Sea Sharks, a 1950s’ tale about modern slavery that jumbles up comical prejudice and passionate anti-racism, tolerance and Islamophobia, sympathy and condescension, human rights discourse and dehumanizing, racialized artwork, including a vast web of characters portrayed with different attitudes along this spectrum…

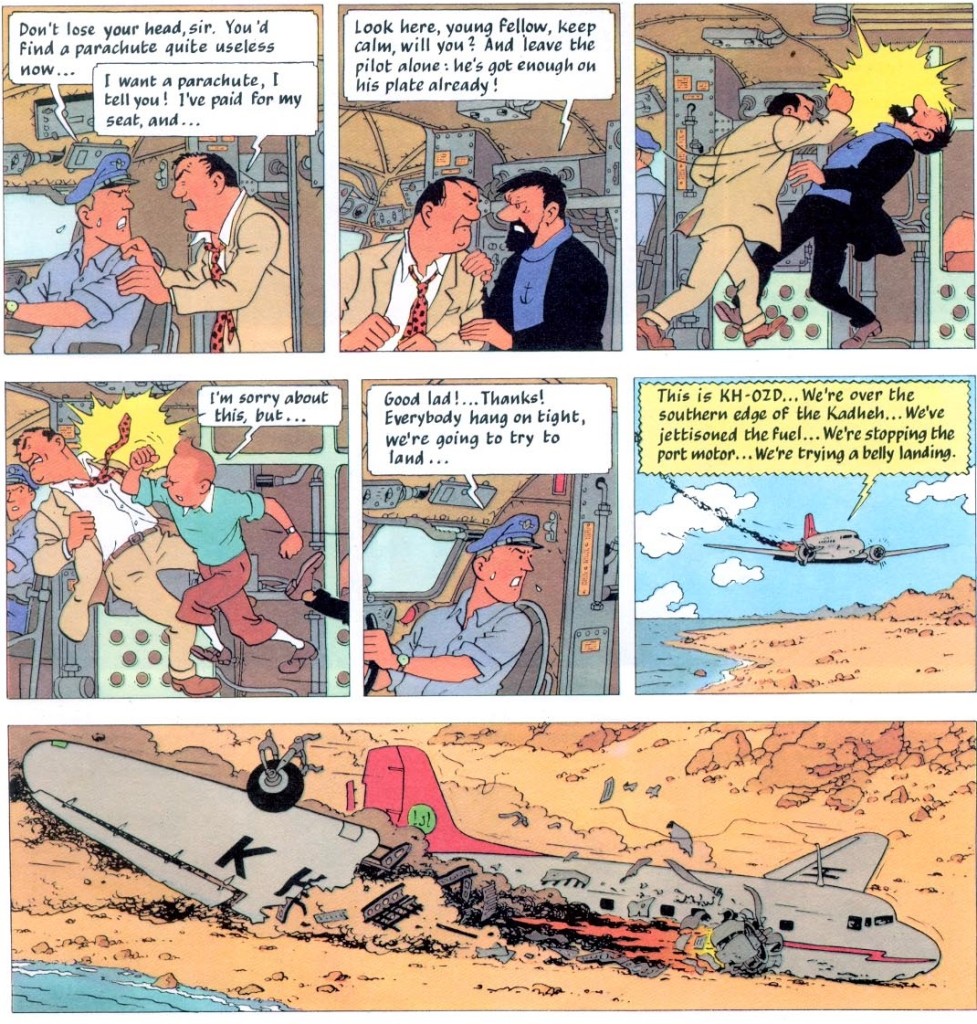

The Red Sea Sharks

The Red Sea Sharks

(By contrast, I think Hergé was quite deft at handling the – sadly still quite topical – issue of the discrimination of Romani people in Europe, in The Castafiore Emerald.)

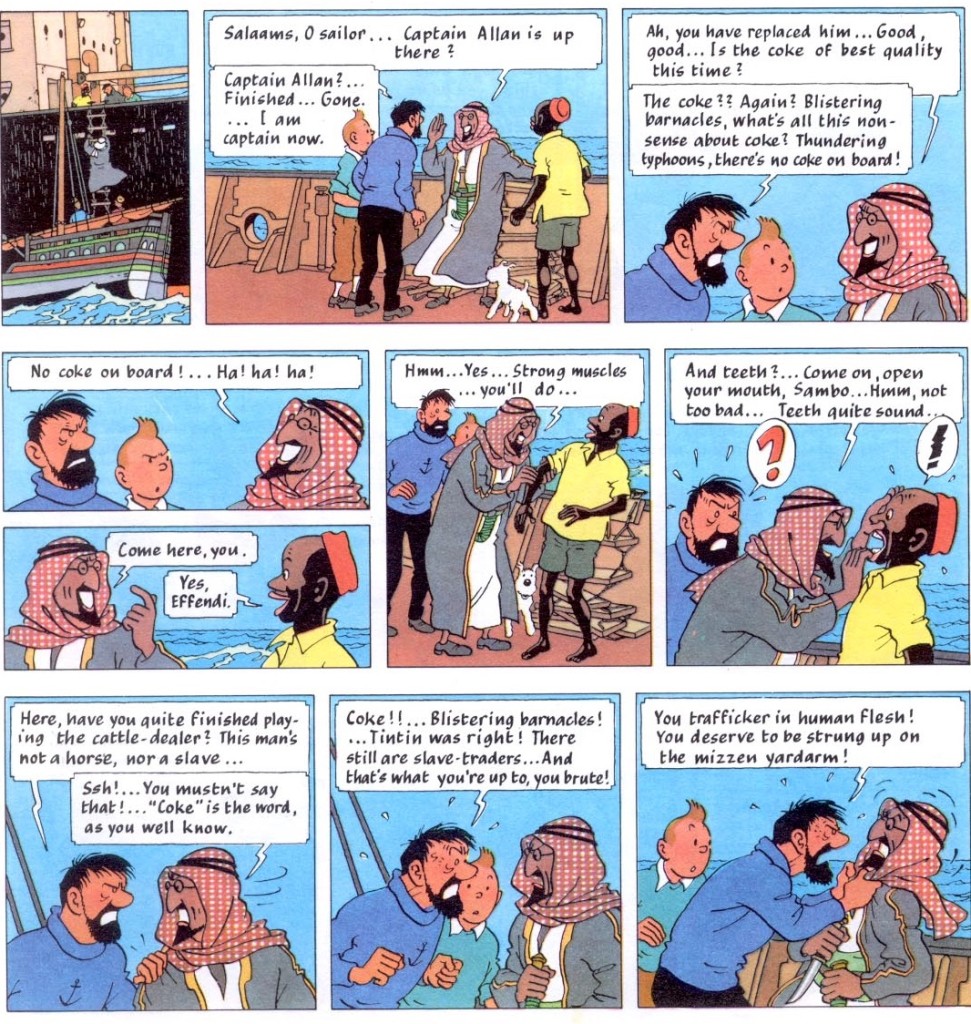

Indeed, for all of Hergé’s positivist and Eurocentric mindset, curious moments of tension keep popping up (no wonder we’ve gotten a whole field of studies devoted to his work, with a host of specialized critics and scholars – so-called Tintonologists – dissecting its many layers…). Just before Tintin and Haddock embark on a journey that will eventually take them to Peru, following the trail of an Inca mummy’s curse and encountering sinister indigenous conspiracies and ignorance along the way, we get this intriguing exchange about archaeologists pillaging foreign ruins:

The Seven Crystal Balls

The Seven Crystal Balls

(I’m not sure if this is meant to represent an illuminated voice of reason or a supposedly conservative viewpoint, especially as Tintin doesn’t explicitly reveal his own stance on the issue…)

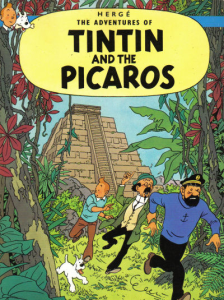

As usual, I am particularly interested in the depictions of international politics. The Blue Lotus denounces the Japanese occupation of China (depicted in a frantic montage similar to the one from Tintin in America above, once again using hyper-compressed storytelling to a powerful effect). The Calculus Affair has the secret services from fictional European powers competing for the plans of an ultrasonic device, at the height of the Cold War, with the heroes taking a pacifist moral stance (the issue isn’t which nation gets its hands on the invention, but the very fact that anyone could weaponize it). The Broken Ear cynically mocks Latin American dictators – as well as revolutionary rebels – as prepotent, selfish, and corrupt, although it also takes a pointed jab at Anglo-American capitalism, with oil companies and arms dealers promoting an entire war in the name of profit. Hergé returned to the latter themes and setting forty years later, in the mid-1970s, with Tintin and the Picaros, whose closing panels are a devastating indictment of power politics (positing that, even if Tintin could orchestrate a bloodless coup, the Third World needed much more than that).

Land of Black Gold merges plot threads about looming war, sabotage by an unidentified foreign power, and corporate competition for oil exploration. The fact that the full explanation for this conflation is amusingly sidestepped at the end (much like Hitchcock would do in North by Northwest) reflects the book’s own convoluted origin – its story was first serialized at the dawn of WWII, from September 1939 until May 1940, when it was interrupted by the German invasion of Belgium, and was finally completed a decade later, from September 1948 to February 1950, at the dawn of the Cold War. As if this wasn’t enough, Land of Black Gold was then redrawn in 1971 (i.e. during the Cold War’s détente phase) by Hergé and his assistant Bob de Moor, at the request of the British publisher Methuen, transferring the setting from UK-administered Palestine to a fictional Middle Eastern state (to which Tintin returned in The Red Sea Sharks, arguably the most politically rich book in the series, interconnecting several facets of international relations, from arms deals to human trafficking, from Latin American and Middle Eastern coups and civil wars to supporting bits by Soviet and American players…).

All in all, we get a sinuous tour through mid-20th-century geopolitics, even if the political intrigue is always at the service of the stories, not the other way around. Although I suspect Hergé was truly interested in the changing world around him, Tintin’s realism seems more like a sparse condiment than like a major concern. Hell, with their abundant tunnels, trapdoors, and disguises, these comics hit that sweet spot of unabashed pulpy entertainment, the kind you also find in many episodes of Mission: Impossible (like ‘The Cardinal,’ ‘Operation Heart,’ or ‘Old Man Out’), delivering a non-stop barrage of two-fisted thrills.

The Red Sea Sharks

The Red Sea Sharks

It’s hard to overestimate how much of Tintin became the template for a certain brand of lighthearted adventure fiction. In Eurocomics, its influence ranges from the cartoonier Spirou & Fantasio to the more adult-oriented Blake and Mortimer. In cinema, besides the live-action adaptations (Tintin and the Golden Fleece and Tintin and the Blue Oranges, both featuring original storylines), these comics inspired plenty of fun movies, such as the obscure Balearic Caper or the more famous (and awesome) That Man from Rio, itself a pretty blatant inspiration for Steven Spielberg’s Indiana Jones pictures (together with Fritz Lang’s The Spiders, Jerry Hopper’s Secret of the Incas, and Lewis R. Foster’s Hong Kong). Spielberg himself would later go directly to the source in 2011’s The Adventures of Tintin: The Secret of the Unicorn (which makes up for what it lacks in depth through relentless action scenes).

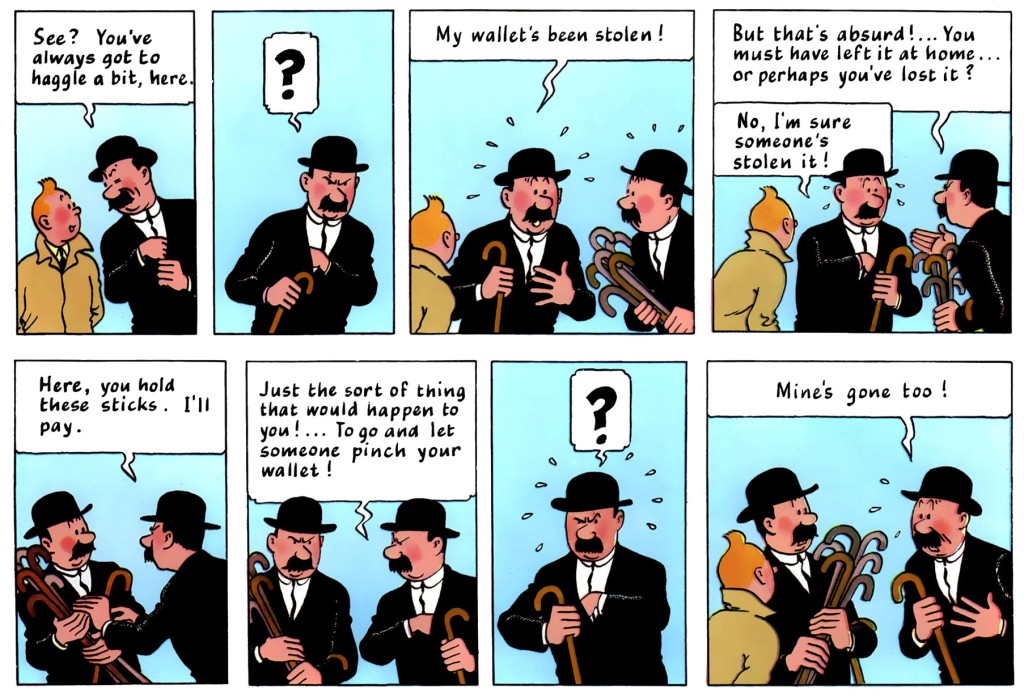

Although less obvious, I’d say you can also draw a clear line to the 1960s’ Fantômas movies and to the original Pink Panther film series, which shared similar aesthetics and physical comedy (albeit naughtier), with Inspector Clouseau coming off as a composite version of the hilariously incompetent police brothers Thomson and Thompson (aka Dupont and Dupond).

The Secret of the Unicorn

The Secret of the Unicorn

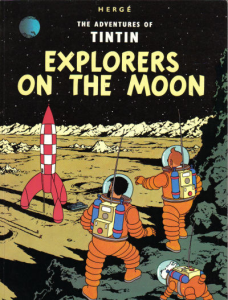

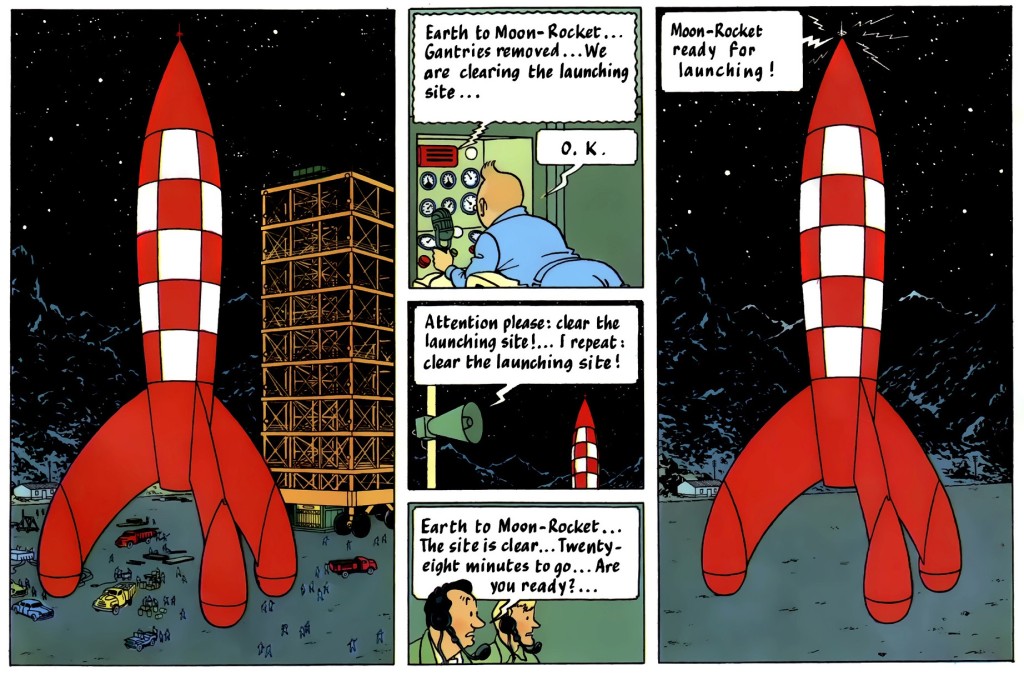

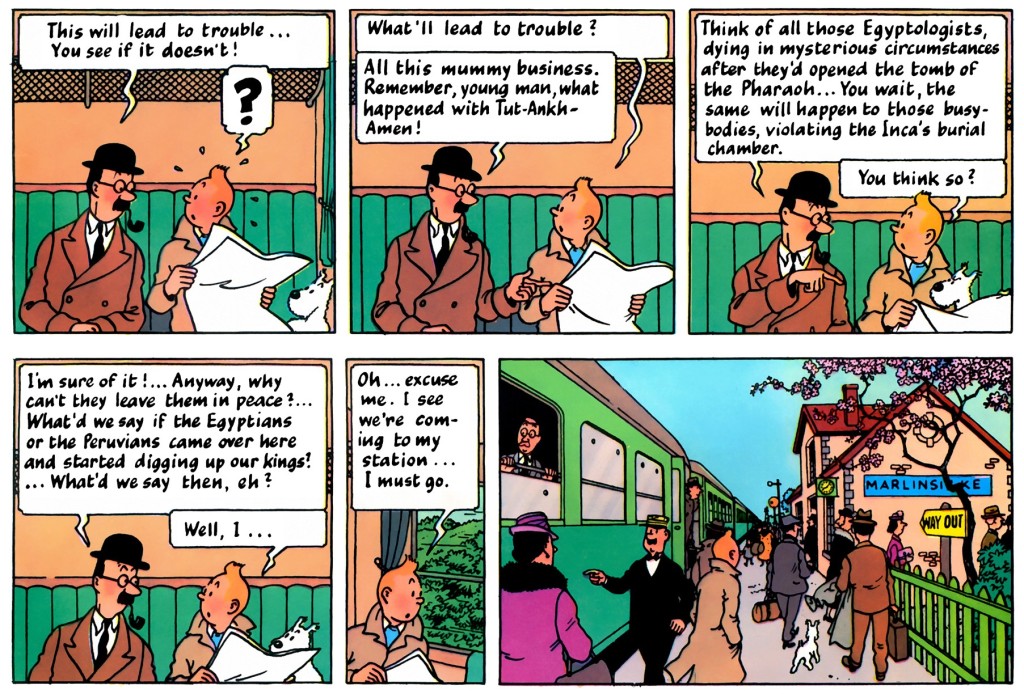

Speaking of cinema, before I finish, as a film geek I must point out the similarities between the series’ most acclaimed entries – Destination Moon and its sequel – and Irving Pichel’s movie of the same name, which likewise came out in 1950. Besides anticipating the mechanics of space exploration with impressive detail despite having been conceived almost two decades before the actual moon landing, these works also share a Cold War-ish subplot about international competition in the space race.

What I most admire, however, isn’t the relatively accurate depiction of space travel, but the way the comics capture the sense of going on a daunting voyage. Even re-reading these books now, in an age when billionaires keep visiting the edges of the Earth’s atmosphere at will, it’s stirring to see Tintin and his friends fearfully embark on this journey… and it’s just as amazing to see Hergé smoothly blend tension, humor, wonder, and sharp characterization into a single sequence: