Like I mentioned in the blog’s latest manifesto, Gotham Calling is no longer focusing primarily on Batman comics, but that doesn’t mean we’re moving too far way… For instance, this week we’ll have a look at another DC comic featuring a dark crimefighter and a classic run written (mostly) by Denny O’Neil – namely the ultra-atmospheric The Shadow (1973-1975).

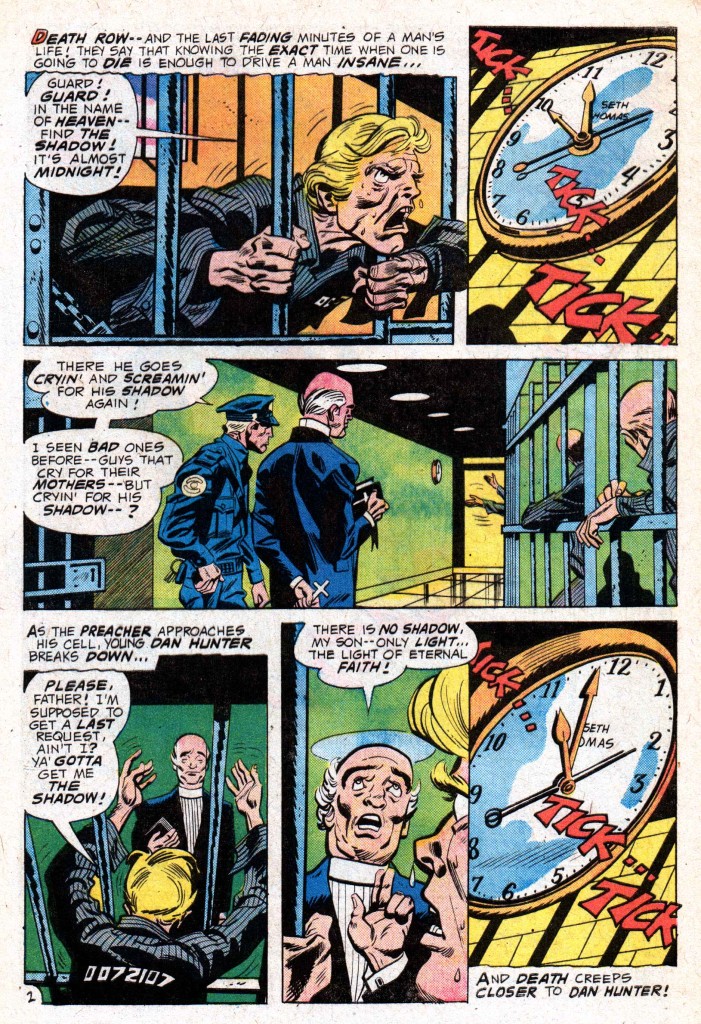

The Shadow #1

The Shadow #1

As some of you are no doubt aware, the Shadow is an iconic vigilante created by Walter B. Gibson (with the pen name of Maxwell Grant) in the early 1930s. The character actually started out as the narrator of an anthology radio show before Gibson developed him in pulp magazines, but it was the literary version that truly established the Shadow as we know it. In turn, that version was adapted to its own popular radio drama later on in the decade.

The deadly Shadow, who had picked up hypnotic abilities (i.e. ‘the power to cloud men’s minds’) in the exotic Orient (because Orientalism was a major leitmotif of 1930s’ pulp fiction), worked with a crew of agents, including – to use O’Neil’s helpful definitions – man-about-town Harry Vincent (the Shadow’s hands), the clever Margo Lane (his eyes), ex-boxer cabbie Shrevy (his legs), and communications expert Burbank (his ears). Besides his sinister laugh, the Shadow has become associated with a handful of catchphrases, most notably the intro from his radio show (‘Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows!’) and the episodes’ recurring final lines (‘The weed of crime bears bitter fruit! Crime does not pay… The Shadow knows!’).

DC got the rights to publish a Shadow comic during the 1970s’ pulp revival. Denny O’Neil was a solid choice to edit and write the series, as he had already proven his pulpy sensibilities through his fan-favorite Batman run (and he would further demonstrate them with his work on Doc Savage ten years later).

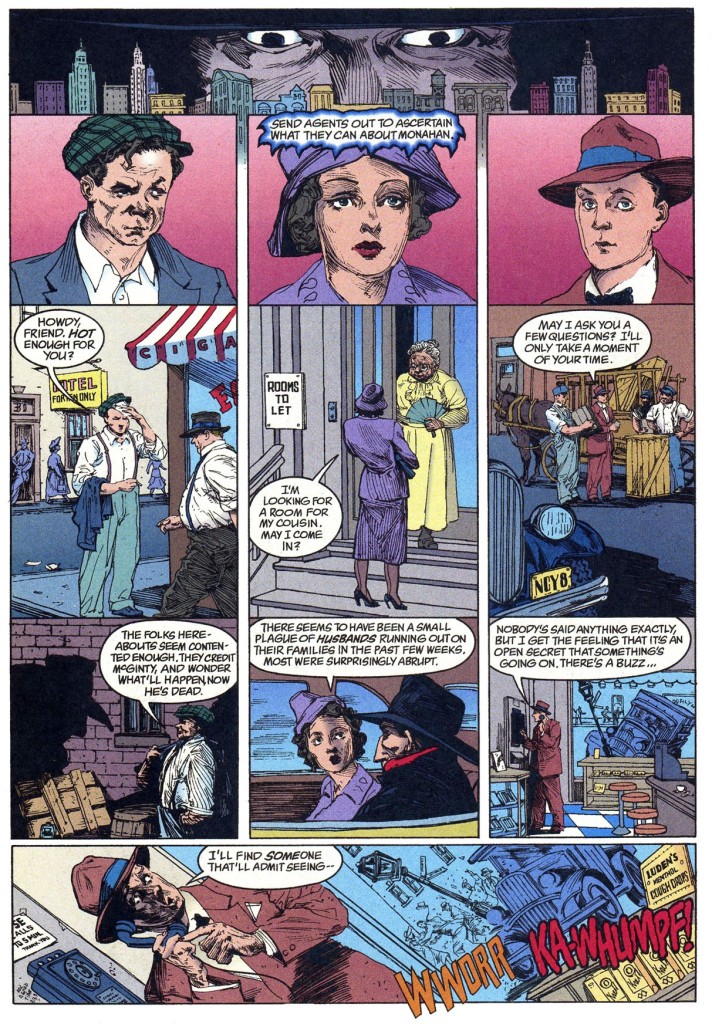

O’Neil threw himself at the material, sticking to the original setting of Depression-era New York City while channeling old-fashioned detective yarns… The very first issue featured a neat gimmick – early on in the story, readers were shown an enigmatic message while a caption box teased them: ‘Have you cracked the code? If not, see the page entitled “The Shadow Knows” following this adventure!’ And, sure enough, the back matter at the end included the code’s solution.

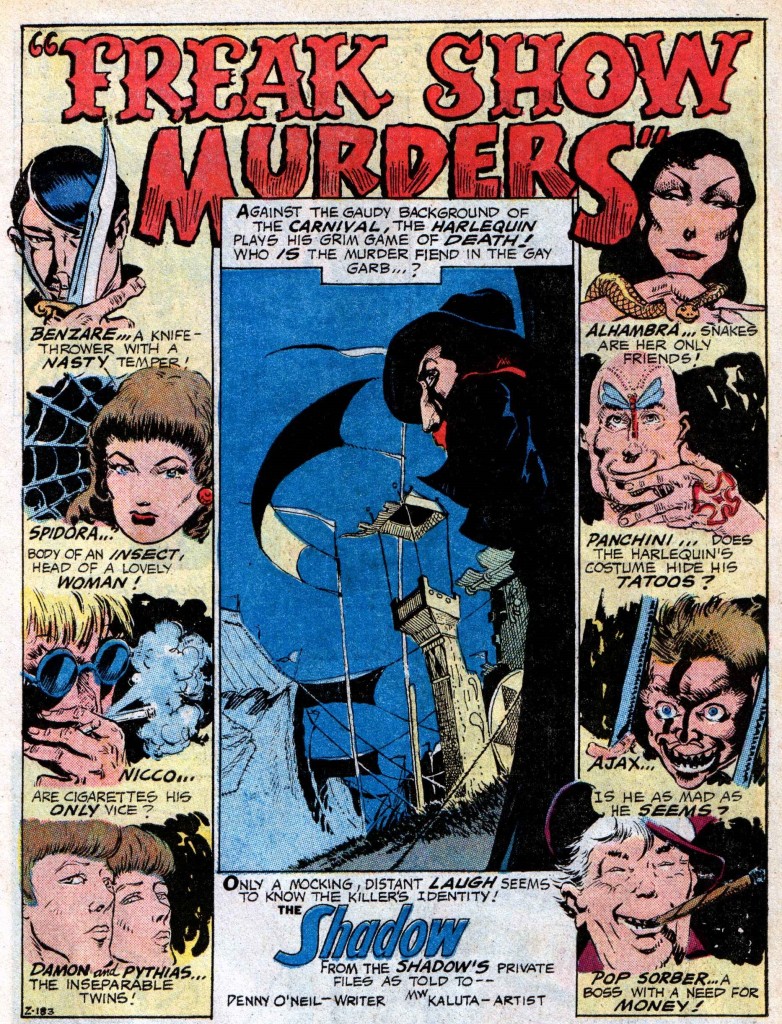

His second story was a whodunit, complete with an opening page establishing the cast of suspects:

The Shadow #2

The Shadow #2

In tales such as this one, Denny O’Neil used the fact that the Shadow was a master of disguise to add an extra layer of mystery. The readers (like the characters in the story, including the Shadow’s own crew) were not sure whom the Shadow was posing as, so there was often a moment when someone would suddenly reveal himself as the protagonist (and more experienced readers would start looking for that someone early on, trying to anticipate the twist).

To make matters even more hazy, in issue #8 we learned that rich playboy Lamont Cranston – who had been presented as the Shadow’s civilian alter-ego – was apparently just another agent acting as a front. Like in the original pulps, the Shadow occasionally borrowed Cranston’s identity (in one story, Harry Vincent even has to get him out of Canada because the team is going on a mission to Niagara Falls and they don’t want to risk having two Cranstons around). In turn, the Shadow’s true identity remained vague and elusive, thus furthering the sensation that he was an almost elemental force of justice.

The Shadow’s relative lack of characterization (slightly compensated by his supporting cast) probably doesn’t work for everyone, but I dig this kind of murkiness. The character was a shamelessly scary, unlikable psychopath whom you rooted for (with a perverse glee) because he was – at least in the best tales – basically fighting forces that were manipulatively presented as *even* scarier and more unlikable! You can draw a direct line from this run to many subsequent stories featuring the Punisher or the Dark Knight.

The latter connection was stressed by O’Neil himself, who wrote a couple of Batman issues – #253 and #259 – where the Caped Crusader diegetically established how one character had influenced the other…

Batman #253

Batman #253

(These are OK comics, but not as fun as Scott Snyder’s, Steve Orlando’s, and Riley Rossmo’s Batman/The Shadow: The Murder Geniuses mini-series, which is super-madness all the way!)

Indeed, it’s not surprising Denny O’Neil ended up working on the two properties. He has always felt quite at home penning fast-paced, two-fisted adventure and hardboiled crime (traits he later successfully developed in his influential run on The Question). He tends to come up with set pieces that, even when they are not entirely consistent from a logical point of view, nevertheless work on some visceral level, either by providing a cool visual or by conveying the hero’s badassery in a particularly satisfying way.

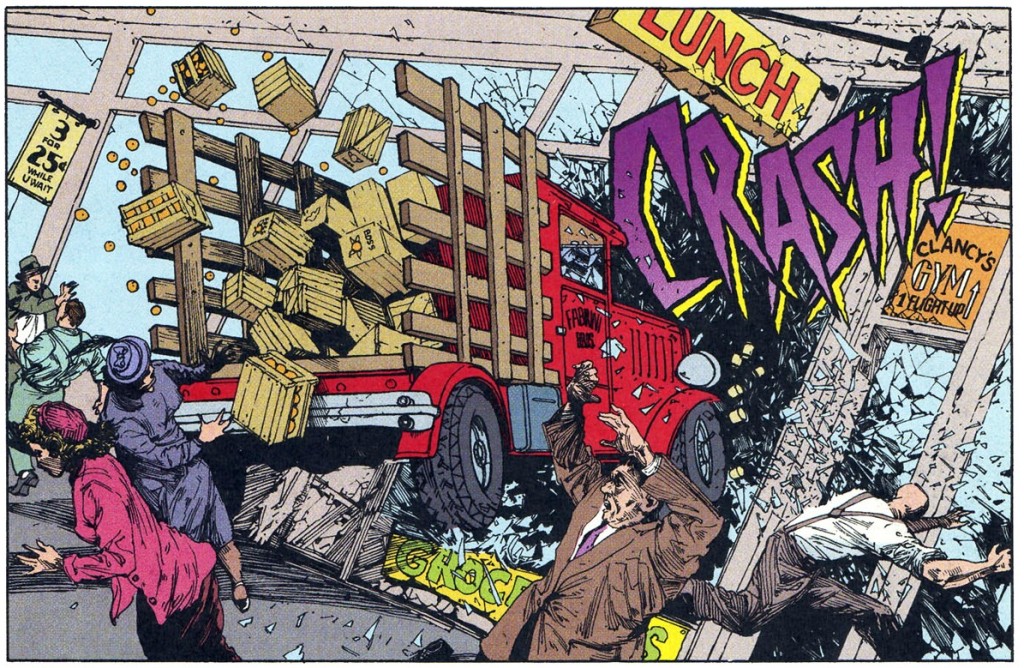

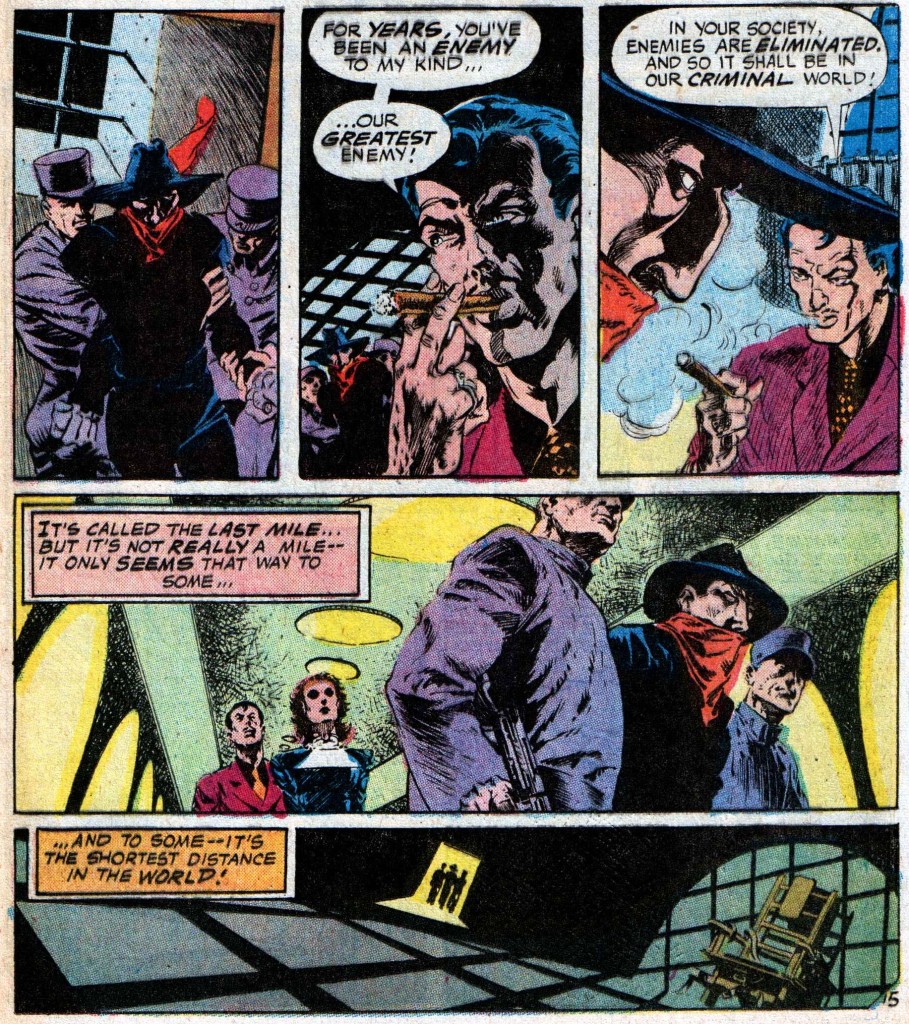

For instance, in ‘The Kingdom of the Cobra’ (issue #3), a rather run-of-the-mill thriller is elevated near the end through this awesome sequence:

The Shadow #3

The Shadow #3

You can feel the enthusiasm of everyone involved. In the back matter, O’Neil and his assistant Allan Asherman pretended that the Shadow was real and was monitoring their work. Issue #9 also featured a text piece on the Shadow’s mass media history, written by colorist – and Shadow aficionado – Anthony Tollin.

That said, the writing was somewhat uneven, with more than a fair share of plot holes and contrivances… Moreover, because the villains were largely forgettable and the Shadow such an unstoppable force, there wasn’t much tension overall. At the end of the day, what really carried the comic wasn’t the cast or the stories, but its mood. (This is also true of the two fill-ins written by comics scholar Michael Uslan, including ‘The Night of the Avenger!,’ which crossed over with Justice, Inc.)

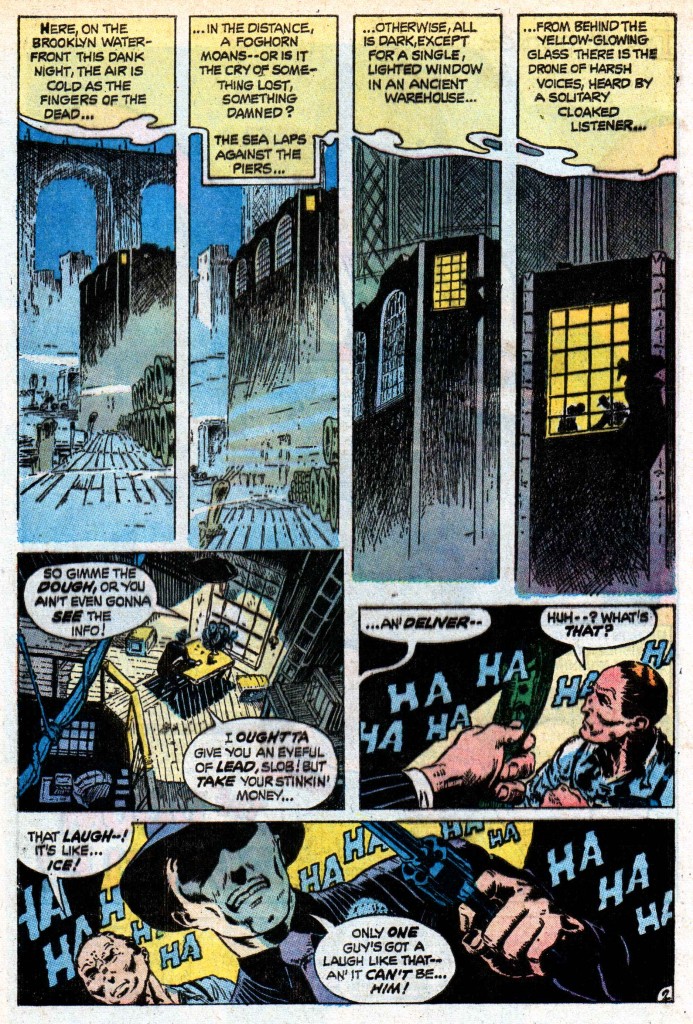

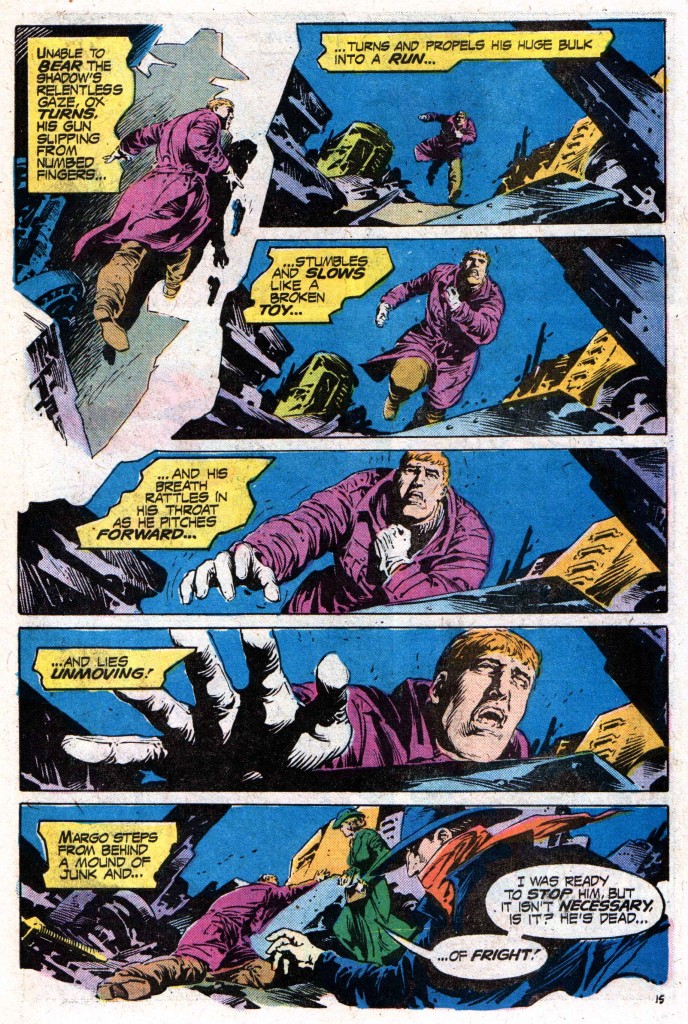

To say that the mesmerizing atmosphere was the key selling point is not to dismiss O’Neil – it just means acknowledging that his main contribution wasn’t as the comic’s writer, but as the editor. After all, he found a perfect line-up of artists to deliver the series’ required noirish vibe, starting with Michael Wm. Kaluta:

The Shadow #6

The Shadow #6

Mike Kaluta’s acclaimed work (in issues #1-4 and #6) paid homage to pulp magazine covers, as tilted angles framed old cars, stylish dames, and armed crooks wearing fedoras. His luscious renditions of smoke and fog (or, as in the image above, of rain and puddles) beautifully merged with O’Neil’s purple prose. It also feels a bit like you’re watching one of those lesser known FDR-era crime flicks, such as William Keighley’s Bullets or Ballots or William Wellman’s Looking for Trouble.

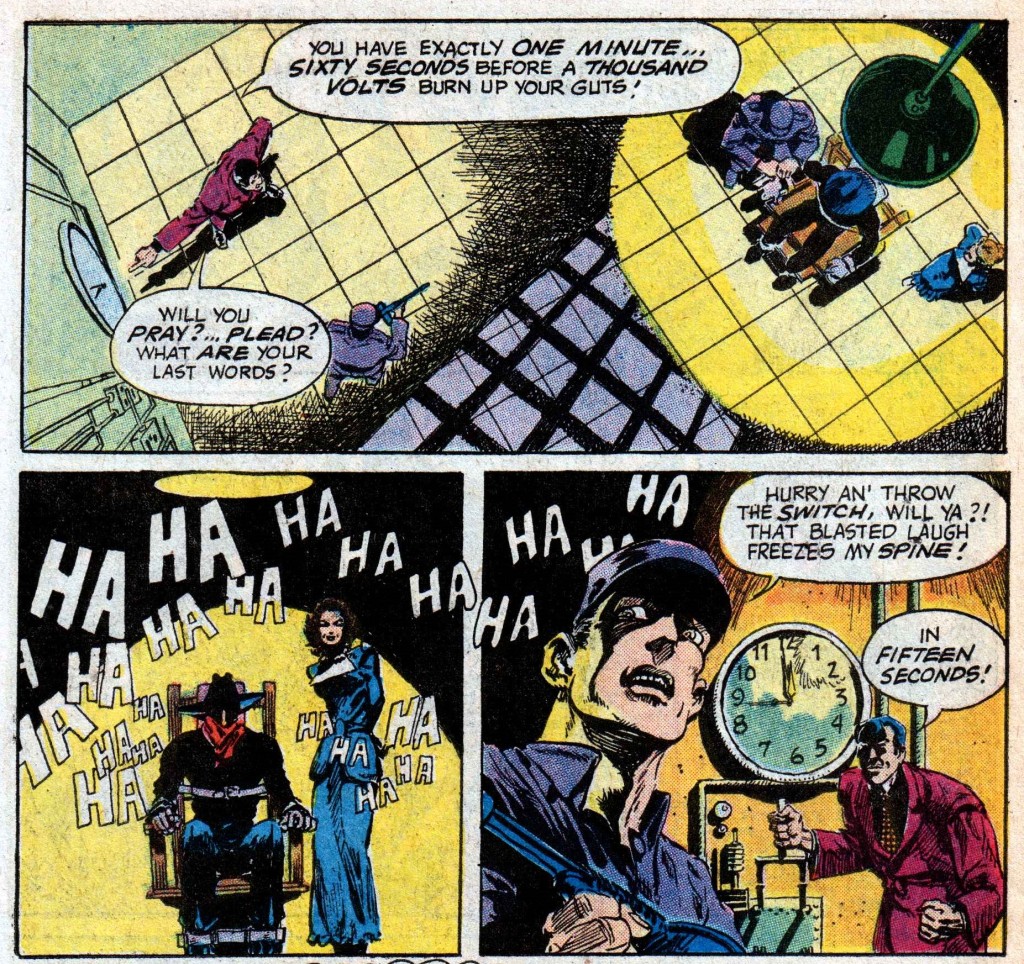

In the series’ final issues, the art was provided by E.R. Cruz, who adopted a similar approach. I especially like his cinematic pace in this sequence:

The Shadow #10

The Shadow #10

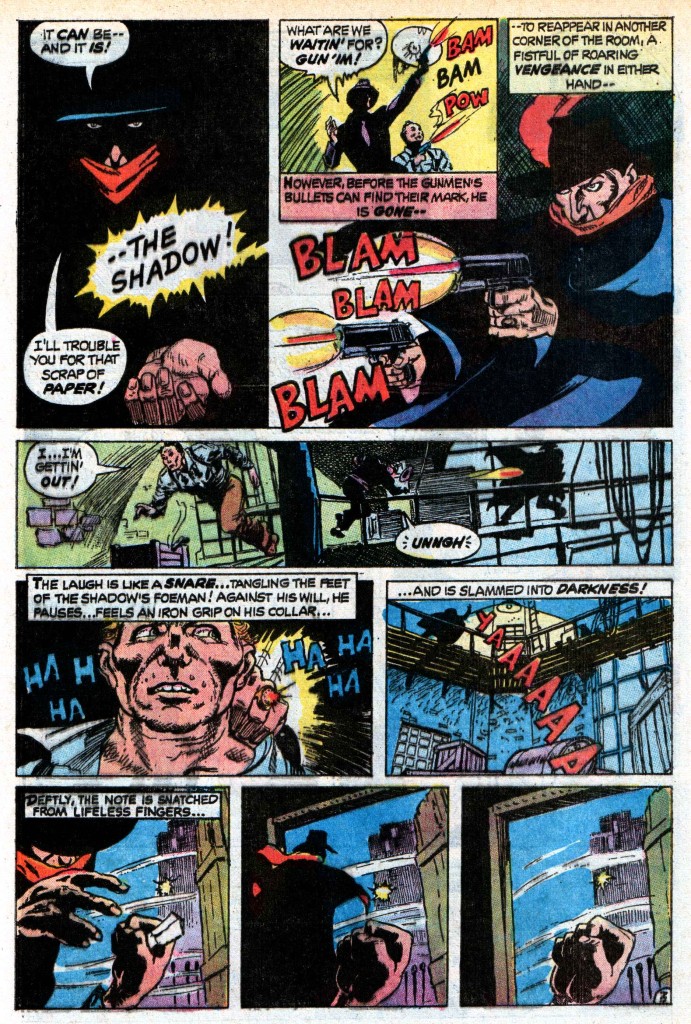

Between Kaluta’s and Cruz’s runs, Denny O’Neil made the brilliant decision of handing over the art duties to Frank Robbins for a few issues. Apparently, Robbins’ cartoony style was not very popular at the time, but I think his retro-looking, expressionistic pencils are perfectly suited to this kind of material:

The Shadow #9

The Shadow #9

Plus, Frank Robbins’ work had a comedic tone and timing that both O’Neil and Uslan wisely mined, thus sort of anticipating DC’s more humorous take on The Shadow in the mid-to-late 1980s. Although there is little doubt that, for the most part, the closest successor to this series was Gerard Jones’ and Eduardo Barreto’s The Shadow Strikes!, scenes like the one below – with the Shadow and Margo Lane going undercover as a married couple – wouldn’t look out of place in middle of Andrew Helfer’s and Kyle Baker’s iconoclastic run…

The Shadow #9

The Shadow #9

In 1988, Marvel published a coda to O’Neil’s and Kaluta’s run in the form of the graphic novel The Shadow: 1941 – Hitler’s Astrologer (with softer inks, by Russ Heath, and lighter colors, by Mark Chiarello, Nick Jainschigg, and John Wellington). Hitler’s Astrologer told a nasty adventure that threw the Shadow into World War II. It had a twisted premise (which involved the Shadow trying to usher in Nazi Germany’s invasion of the USSR) and a knockout climax (which I won’t spoil here), but of course the high point was watching this quasi-fascist anti-hero and his gang go up against all kinds of other fascists, including a group of Irish fifth columnists!

Michael Kaluta actually went on to become a Shadow writer himself, co-writing with Joel Gross a handful of comics for Dark Horse in the mid-1990s. Dark Horse probably hoped to cash in on Universal Pictures’ attempt to bring the Shadow to the big screen in 1994, but that film turned out to be much campier than the comics, which stayed closer to the source material. (A baffling, entertaining mess in which a scenery-chewing Alec Baldwin turns into smoke and uses elaborate gizmos to fight a shockingly orientalist villain, Russell Mulcahy’s The Shadow is best seen, not as a crime movie at all, but as part of the mid-90s’ wave of eccentric, visually stylish superhero adptations, alongside The Mask, The Crow, and Batman Forever.)

Kaluta’s and Gross’ first collaboration, the mini-series In the Coils of Leviathan, even included lengthy pastiches of the original pulps in the form of prose sections with some of the most purple descriptions I’ve ever read: ‘With mounting dread, as one might unwrap an unknown, sodden bundle, the sky dinges another point toward un-dark, hands trembling and eyes flickering to either side – will the twisted lump laying astride the curb be a discarded coat of pain, tossed off with someone’s forgotten life, the finger-spread pentalinear arc of smeared crimson mapping the final staves of its pointless symphony? Its surrounding stain the mark of ignorance or ambition?’

(I must admit I absolutely love this kind of hardboiled prose, even at its most over-the-top… Alan Moore has a chapter near the end of Jerusalem mocking it to death and, while I laughed out loud, I couldn’t help but get some genuine *delight* from the barrage of vicious images and expressions!)

Those Dark Horse comics actually share quite a few traits with Kaluta’s previous work with Denny O’Neil, albeit delving much further into the rich setting that is interwar New York City, with all its layers and contradictions. The scripts, while far from perfect, capture the grittiness of the 1930s’ crime scene and the art by Gary Gianni (In the Coils of Leviathan, Hell’s Heat Wave) and Stan Manoukian (The Shadow and the Mysterious 3) is incredibly moody in its own way…