Way before Samuel L. Jackson embodied the role, Colonel Nick Fury was already a household name for Marvel fans, having starred in a string of seminal psychedelic spy comics by Jack Kirby and Jim Steranko back in the 1960s…

Strange Tales #160

Strange Tales #160

(For a hilarious tribute to these runs, as well as to Kirby’s and Steranko’s similar work on Captain America, check out Big Bang Presents #6.)

Since his glory days, though, the cigar-chewing, one-eyed agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. has had an uneven career, both in his own series (I have a soft spot for D.G. Chichester’s run in the early ‘90s) and as a guest in other characters’ vehicles (Elektra: Assassin being a high point). The most memorable take on the property in ages occurred in 2001, when Garth Ennis and Darick Robertson reimagined Nick Fury – in an irreverent 6-issue mini-series published by Marvel’s ‘adults only’ MAX imprint – as an embittered old man having trouble adjusting to the post-Cold War era.

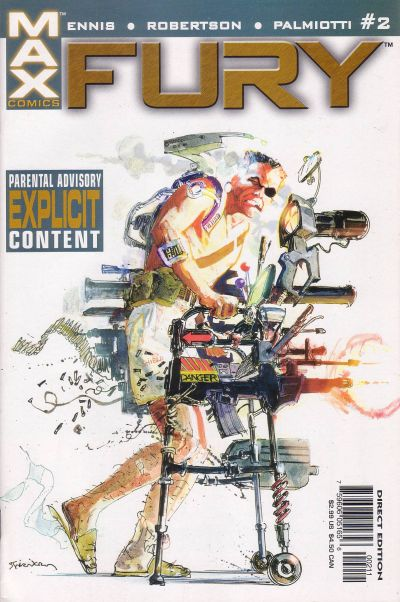

This mini-series – which I’m calling Fury MAX to distinguish it from all the other comics called Fury – was one of several bold creative choices taken by Marvel during the prolific Bill Jemas/Joe Quesada editorial partnership in the early 2000s, along with giving a free rein to Grant Morrison (New X-Men, Marvel Boy, Fantastic Four: 1234) and launching such idiosyncratic runs as Peter Milligan’s and Mike Allred’s X-Force or Brian Michael Bendis’ and Alex Maleev’s Daredevil. By hiring Garth Ennis (fresh off Preacher and The Punisher: Welcome Back, Frank) and Darick Robertson (during the final stretch of Transmetropolitan) to do a book without the Comics Code Authority seal, edited by former Vertigo editor Axel Alonso, it’s a fair bet Marvel’s big shots knew they were bound to get oodles of foul language, gory violence, and pitch-black humor, but I wonder if they anticipated just how subversive things were going to get…

The very first page sets the tone, with a splash of a rugged-looking Colonel Fury pointing a huge-ass weapon and grittily ordering ‘Kill them all.’ Below, the issue’s title warns readers: ‘Be Careful What You Wish For.’ You can pretty much tell from the outset that the series will combine two quintessential Ennis motifs: on the one hand, his flair for iconoclastic takes on beloved, established characters and, on the other hand, his fondness for the stoic, unapologetic ‘man’s man’ archetype. Indeed, Fury MAX reinvents the titular lead both as a nasty bastard (who fantasizes about murdering his adoptive nephew, presumably because the latter doesn’t match his brand of virility) and as an old-school cold warrior who feels emasculated by corporate bureaucrats that (according to the collected edition’s back-cover) are ‘more interested in recruiting highly trained computer specialists and high-priced suits than spies and commandos.’

Fury MAX #1

Fury MAX #1

(Notice the picture of the Helicarrier relegated to the background, signaling changing times…)

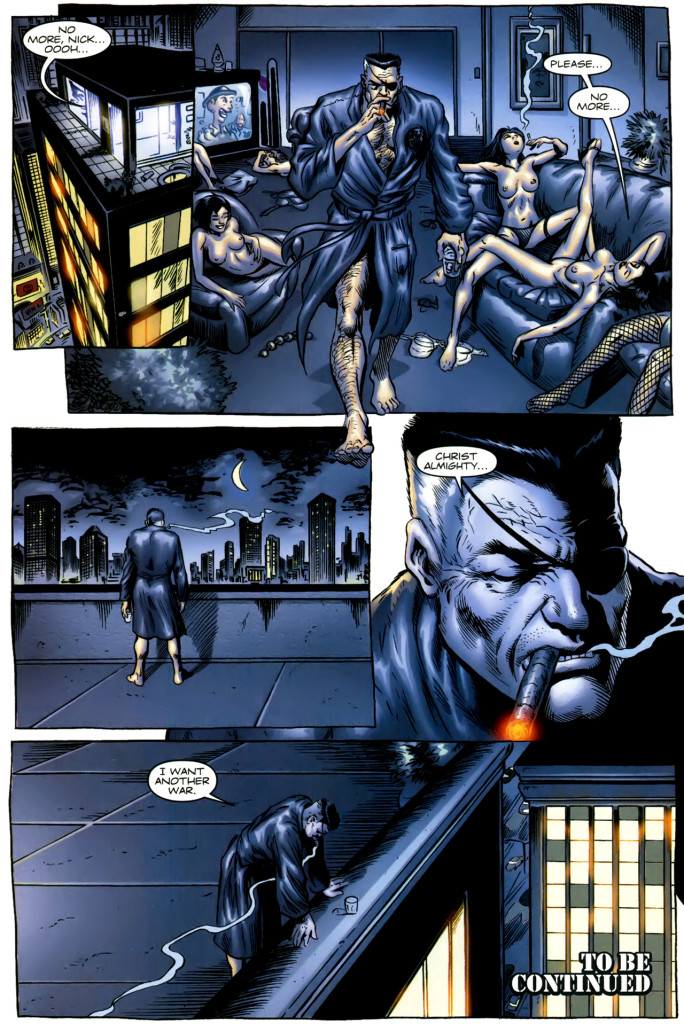

Fury MAX gets some comedic mileage out of the mere act of dirtying up Marvel’s super-agent, taking the piss by placing a recognizable hero in adult situations such as swearing (including plenty of homophobic slurs), screwing hookers, and ruthlessly slaughtering dozens of people. (It was the very early days of the MAX imprint, so this kind of thing still felt relatively fresh… Alias came out at the same time, Cage and The Hood came out in the following year.) Setting aside for a moment Garth Ennis’ penchant for editorializing, there is clearly a humorous slant to scenes like the one where a decadent Nick Fury delivers an outrageous rant about the previous decade: ‘What happened to this country? When did the assholes start running things? How did they get away with the pissant little rules they make us live by? Why do they use ten words to hint at what just one would say? I feel like I blinked and someone turned the place into the United States of Pussies…’

Fury MAX #1

Fury MAX #1

Darick Robertson is a perfect partner-in-crime. It’s not just that his art has always displayed great comedic timing… Robertson visibly delights in drawing over-the-top sex and grotesque carnage. And here Ennis gives him several chances to go wild, whether by depicting a monstrous, disfigured henchman (called ‘Fuckface,’ because this is that kind of comic) or by bringing to life the climactic bloodfest (where Fury rips out an enemy’s entrails and strangles him with his own intestines, because this is also that kind of comic), well-served by Jimmy Palmiotti’s thick inks and the glossy colors of Avalon Studios.

Robertson’s excellent storytelling pace and stylish character designs make the various lengthy ‘talking heads’ sequences utterly compelling, which also works well with Ennis’ characteristically dialogue-rich script.

Fury MAX #1

Fury MAX #1

As you can tell from this scene, there is a revisionist edge to Fury MAX, not unlike what Frank Miller did with Batman in The Dark Knight Returns. It’s as if these comics are showing us how their protagonists – and their worlds – truly were all along, casting even the past in a different light.

This revelatory approach leads to one of the series’ most provocative gestures, namely the heavily implied suggestion that, contrary to what he claims, Nick Fury’s driving motivation is not so much a concern for the weak and the ‘little people’ (which, as shown in his relationship with his nephew, Fury can’t stand up-close), but rather an addiction to the adrenaline of combat. The comic’s central plot involves Rudi Gagarin – an ex-Hydra, ex-Soviet hawk – trying to kickstart a new large-scale geopolitical conflict because he misses the old days (‘Guys like you and me, battling it out with the fate of the world at stake… A war in the shadows, a war the little people never knew about… You set up a government here, knock down a rebel force there… You convince some generalissimo to invade his neighbor… He thinks it keeps the guns coming in, you know it’ll keep coke going out, and all the while you’re fucking the idiot’s wife…’). Revealingly, when he tells Fury about this plan, Fury doesn’t stop him straight away, so Gagarin does end up setting it in motion (by staging a military coup in the strategic Napolean Island), which results in an orgy of violence. In the final images – a callback to the balcony scene shown earlier in this post – we see a melancholic Fury coming to grips with what he has done.

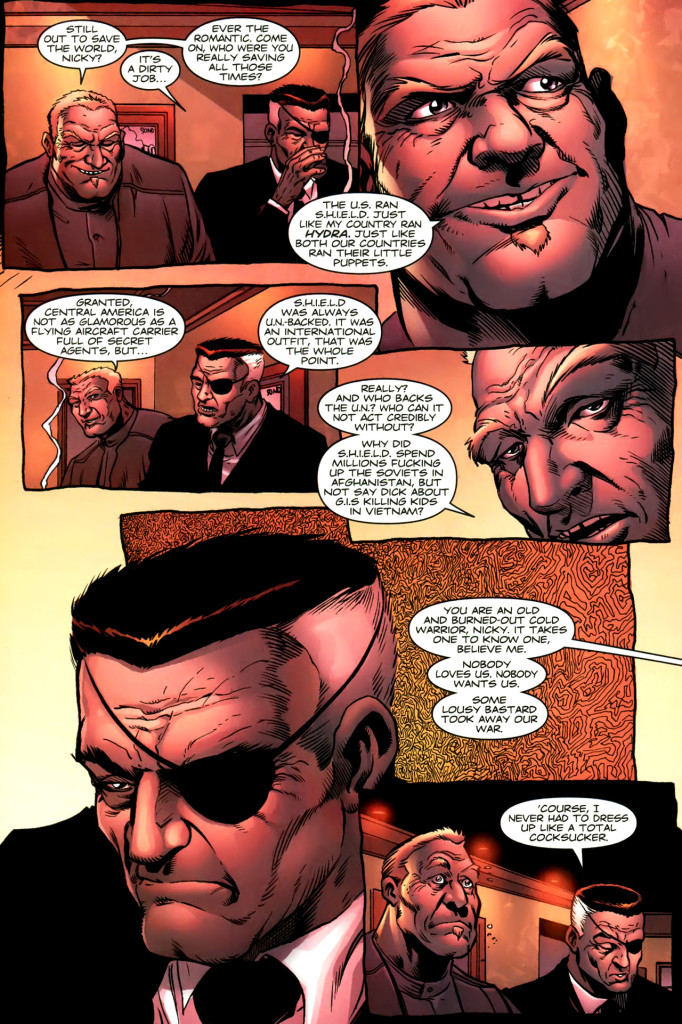

It’s a Garth Ennis comic, so none of this is incredibly subtle. Indeed, a retired Dum Dum Dugan sees right through Nick Fury:

Fury MAX #2

Fury MAX #2

The point is not that Nick Fury and Rudi Gagarin are the same. Despite both embodying military discipline and an overall sense of ultra-tough masculinity (including the desire and ability to satisfy multiple women in one go), the comic acknowledges differences. The nuances are especially clear in issue #4, where Fury’s approach to his crew (‘So long as you do your job you can ask all the questions you want.’) comes across as comparatively less despotic than Gagarin’s (‘Give me further cause for disappointment… and Fuckface will sleep with you.’).

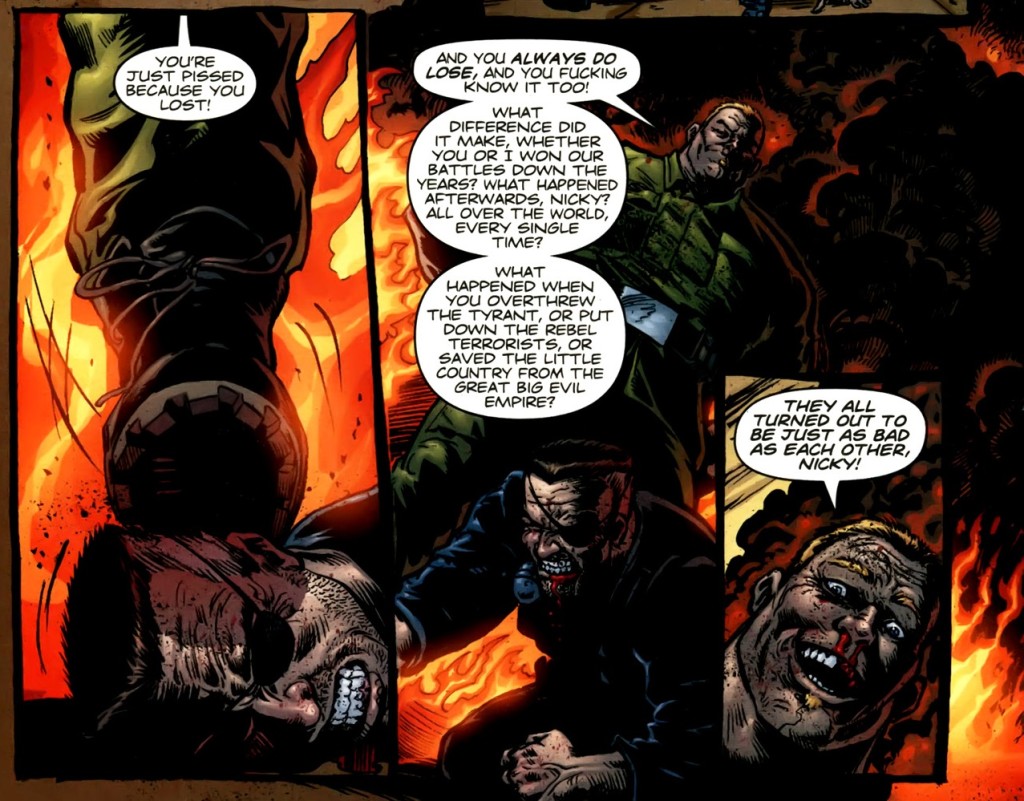

The biggest difference between them is that Nick Fury gets a rush out of fighting for freedom, whereas Rudi Gagarin is gleefully nihilistic, openly admitting that what he enjoys is the great game itself (‘it was like chess with blood…’). You can argue that Fury is more ideological and Gagarin more cynical… or that the former is just more hypocritical and self-deluded than the latter. In any case, their relationship illustrates a core theme of Ennis’ work, namely the ambiguous line separating the notion that you-need-to-be-macho-to-get-shit-done from the sense that getting-shit-done-is-a-pretext-to-indulge-in-machismo.

Fury MAX #6

Fury MAX #6

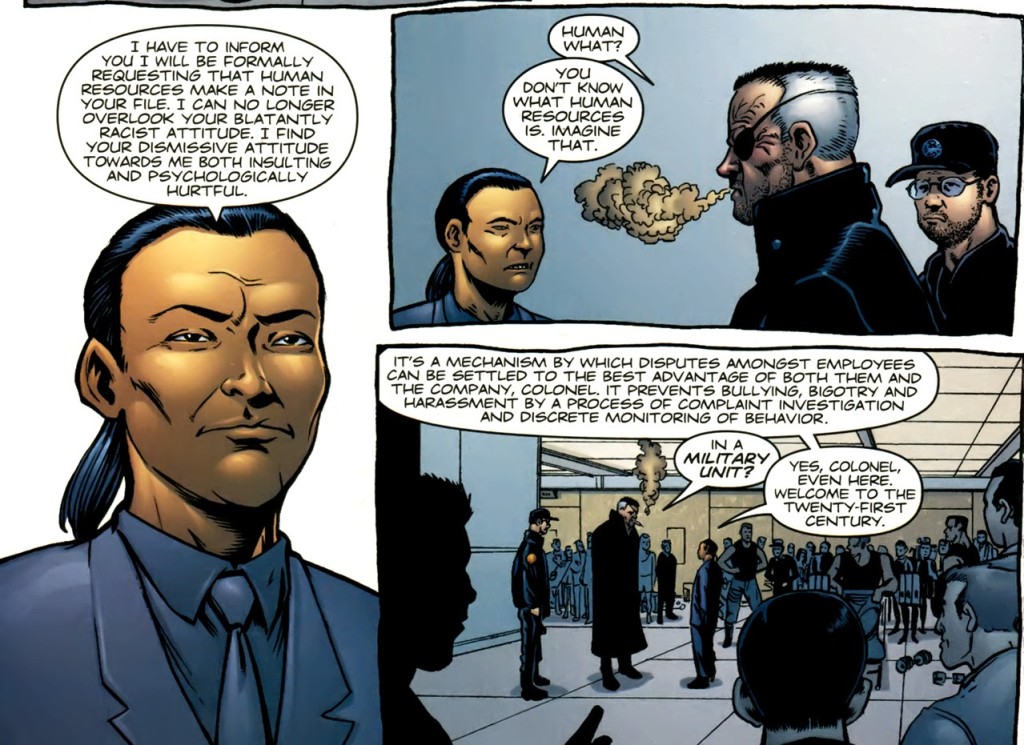

As it should be clear by now, on top of the geeky dimension of character revisionism, Fury MAX is also subversive on more political levels. One of those levels – the least interesting one – has to do with the dated attempts to seem edgy by attacking political correctness. This version of Nick Fury comes across like Clint Eastwood’s cranky, take-no-shit persona in Gran Torino and The Mule – he is a curmudgeon who calls a spade a spade and will only respect you if you don’t get offended.

Fury MAX #3

Fury MAX #3

That said, just like Eastwood’s latest film complicates its benevolent depiction of small-scale anti-PC provocations by pitting them against the wider context of systemic racism (on which the whole premise of the film hinges), Fury MAX also throws its reactionary impulses into seemingly contradictory directions. Ultimately, Garth Ennis’ style fits comfortably into a tradition of British literature – together with the likes of Tom Sharpe’s Ancestral Vices or Ben Elton’s Blast from the Past – that embeds poignant political satire in outlandish off-color comedy.

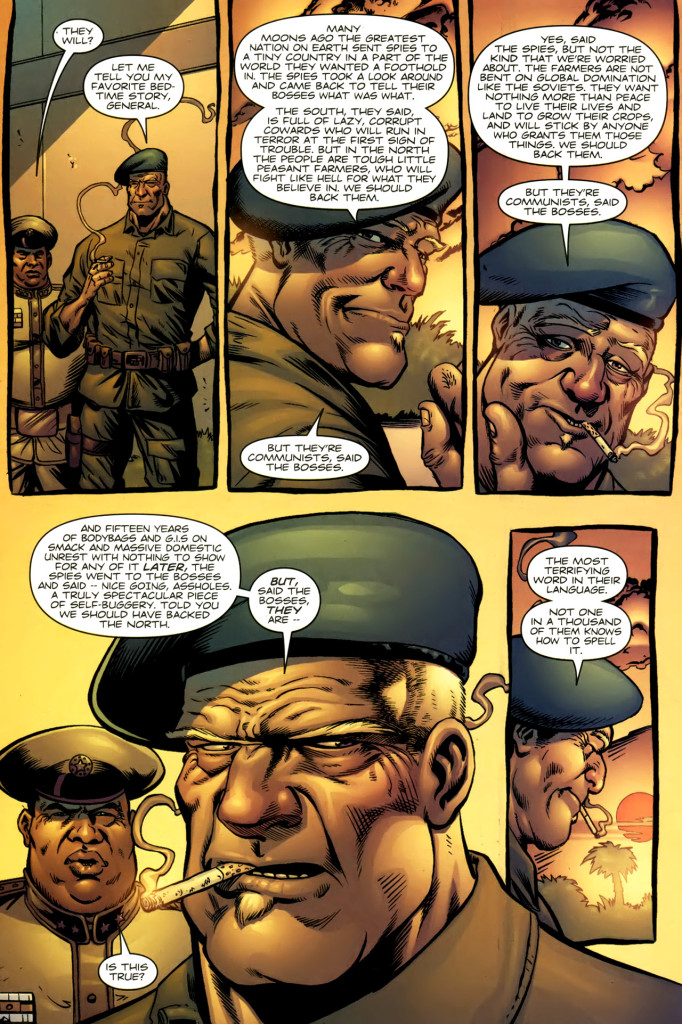

For one thing, Ennis has his share of fun at the expense of North American anti-communism. Indeed, this is a comic clearly plotted (and mostly written, I assume) before 9/11, back when George W. Bush sounded like the most inarticulate president imaginable (‘They say he’s dumb, but what about the people who let him near the microphone?’) and when neocons still seemed to be coping with the loss of their longstanding enemy by looking back at the Cold War rather than throwing themselves at the Global War on Terror… Notably, Gagarin backs a coup by a tropical dictator, General Makawao, because at the time those were still more fashionable as enemies than Muslim fundamentalism.

Fury MAX #3

Fury MAX #3

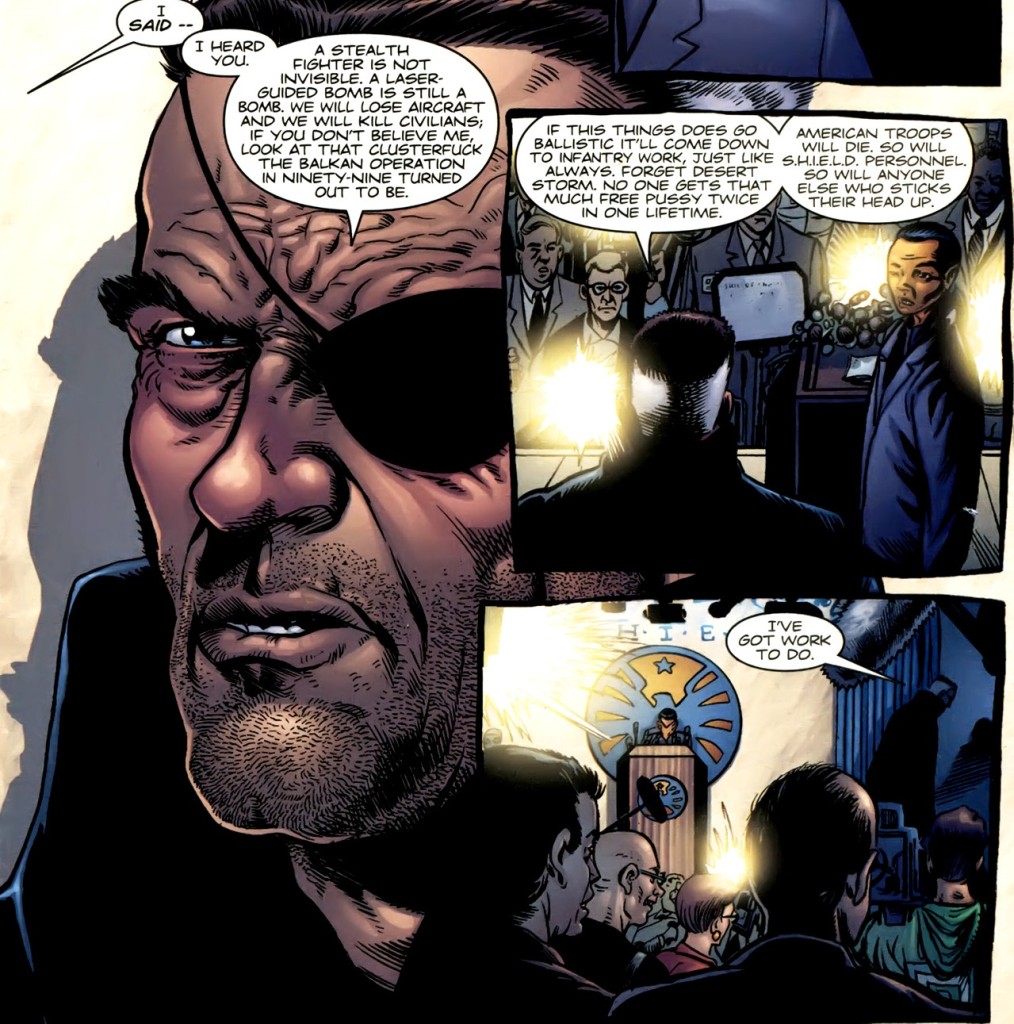

We also get an interesting glimpse into late ‘90s debates on the future of warfare during a conference when Nick Fury bursts out that, for all the talk of stealth and smart weapons, at the end of the day you’re still going to need balls of steel to go to war. At first sight, the scene may look like just another amusing demonstration of Fury’s straight-talking, zero-patience-for-softies-and-tech-nerds attitude but, looking back, it now seems like a prescient warning against the upcoming military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq:

Fury MAX #3

Fury MAX #3

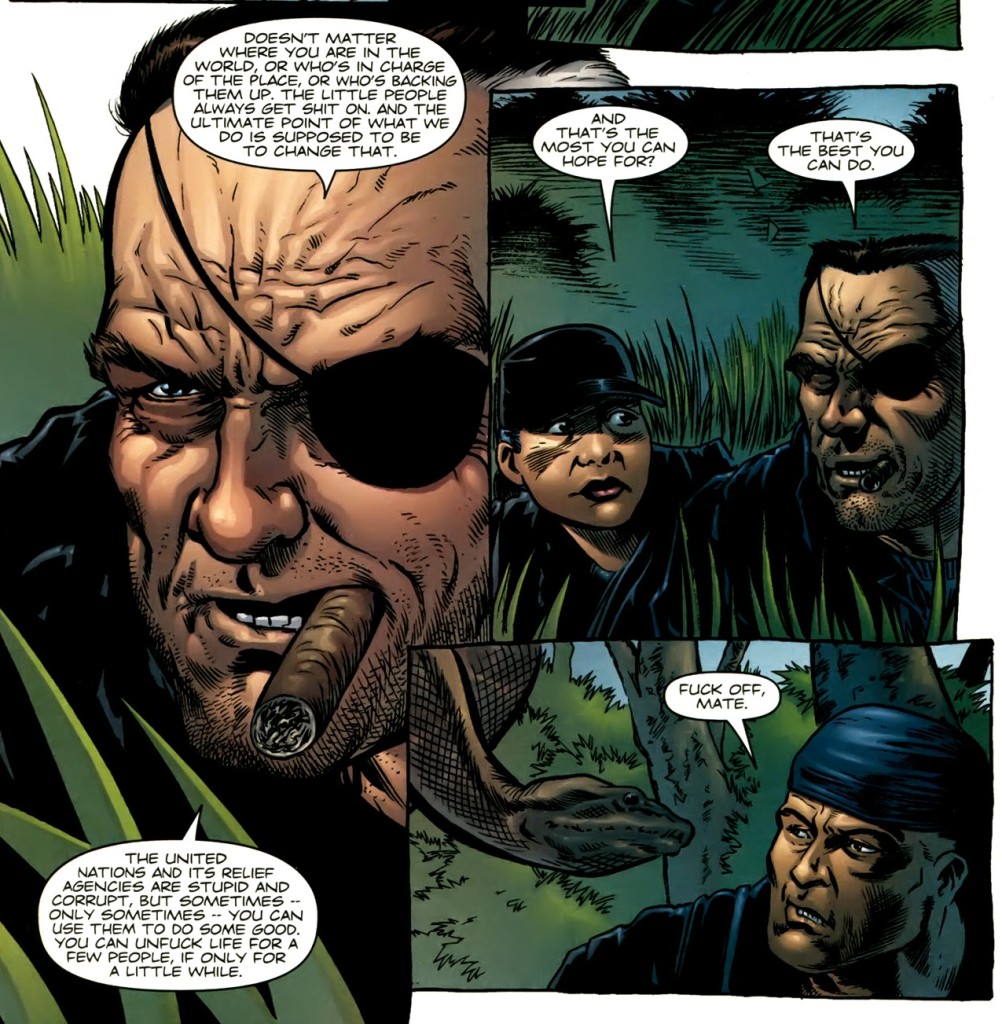

The fascinating thing is that if, on the one hand, Nick Fury seems to represent the Bush-era United States because he’s so eager to embark on yet another ostensibly righteous crusade, on the other hand it’s precisely against the jingoism of the actual U.S. government that he claims to be fighting. Fury frames his mission – and that of the U.N.-backed S.H.I.E.L.D. – as preventing an American intervention in Napolean Island by sorting things out before they escalate into a crisis. As he puts it at one point: ‘This agency is not about to become the U.S. government’s puppet. We exist to do the job – not to fuck up so they can say No more Mr. Nice Guy and carpet-bomb a whole country off the map.’ Or, later, in a pep talk to his crew: ‘the smaller the role American forces play in toppling the Makawao regime, the less excuse the U.S. has to get a toehold afterwards. I’d rather have the U.N. peacekeepers here than some Company-backed fucker a thousand times worse than Makawao.’

Yep, for all the pre-alt-right flavor of some of its rhetoric, Fury MAX still makes the case that, warts and all, the United Nations are at least preferable to American imperialism…

Fury MAX #4

Fury MAX #4

This leads to a great spin on that scene near the end of Rambo II where Sylvester Stallone shoots up the office of a slimy government bureaucrat who had betrayed the American war effort. In this version, Nick Fury takes it out on the bureaucrats of the United Nations because they sold out to U.S. warmongers!

Fury MAX #6

Fury MAX #6

By taking right-wing rhetoric and imagery and hectically putting it in the service of a kind of murky anti-right-wing critique, this scene gloriously sums up Fury MAX – and, in fact, much of Garth Ennis’ oeuvre.