2012’s limited series Fury: My War Gone By is the kind of idiosyncratic, fascinating beast you get in the field of comics, bizarrely merging auteurism-ran-loose with a popular corporate franchise in the form of provocative historical fiction. It’s not just that writer Garth Ennis chose to explore the Cold War through the version of Colonel Nick Fury he had crafted ten years earlier, it’s also that he indulged in so many of his disparate interests and tastes that the ensuing tone is all over the place, appealing to a relatively specific combination of sensibilities (which I happen to share), as My War Gone By veers between sentimentality, detailed military discussion, high politics, and lowbrow comedy, including plenty of explicit language and graphic sexuality.

Fury: My War Gone By #4

Fury: My War Gone By #4

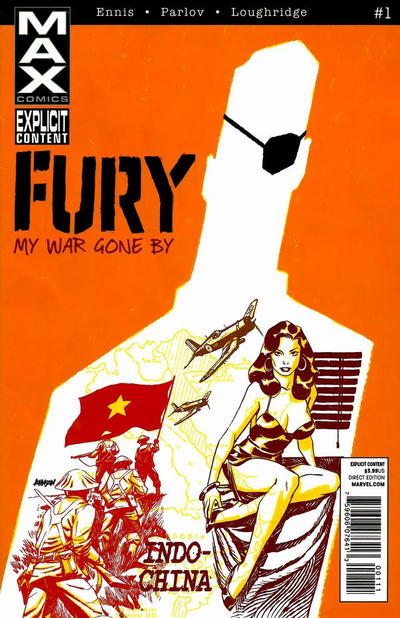

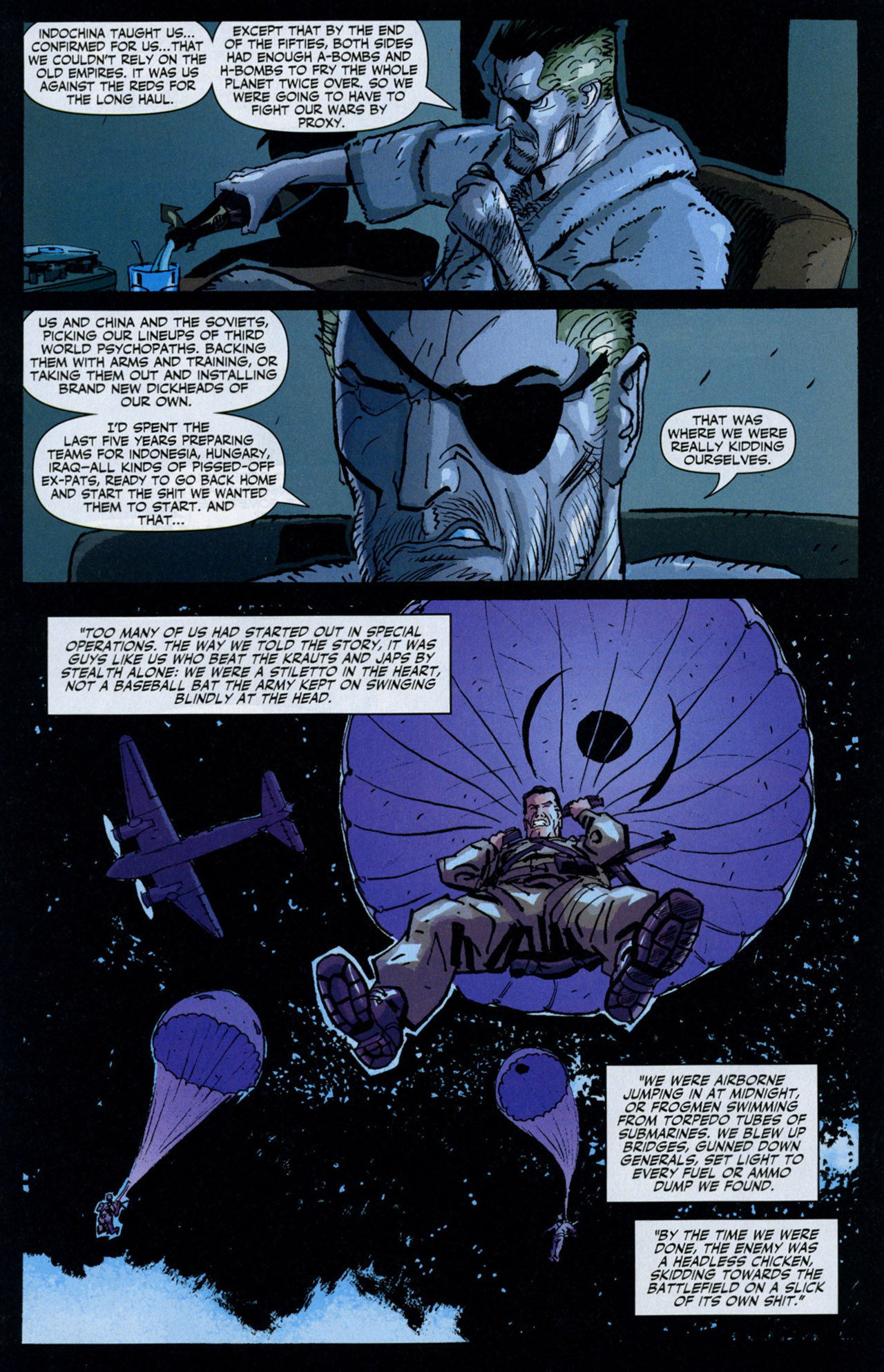

It helps that the whole creative team seems to be on the same page. Artist Goran Parlov always has a nice rapport with Ennis, his page-wide horizontal panels and his exuberant, not-quite-cartoony lines perfectly matching the Irishman’s caustic scripts. The colors are by the great Lee Loughridge, who gives the light in each corner of the world a specific texture, nailing the series’ wide range of moods. Moreover, Dave Johnson’s super-stylish, conceptual covers give off just the right hint of James Bond while making it increasingly clear that this is a separate breed of Cold War fiction. (The issues’ titles are likewise based on intertextual winks, calling back to lines from a variety of thematically-related works, such as poems, novels, films, and even a couple of kickass Pogues tracks… The title of issue #9 ironically alludes to the lyrics of the theme-song from The Spy Who Loved Me.)

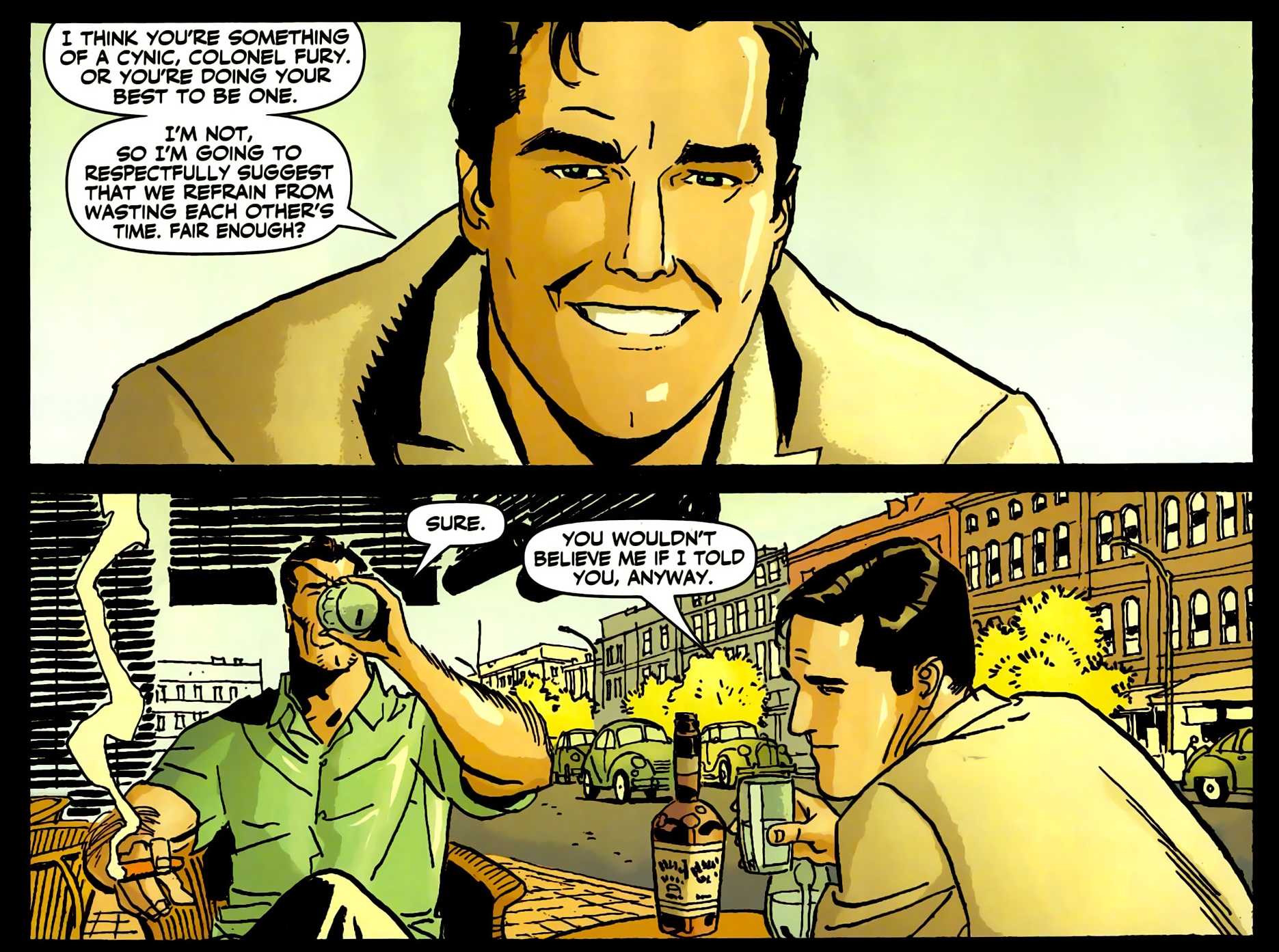

It’s a bleak, ferocious series (if you’re just looking for a breezy romp set in a revised version of Marvel’s Cold War, go look for it in Kathryn Immonen’s and Rich Ellis’ Agent Carter: Operation S.I.N. instead). The structure is rather episodic, each three-part arc engaging with a crisis from a different decade. The first arc takes place in 1954 Indochina, around the time of the Battle of Dien Bien Phu. It introduces the main recurring characters (who represent distinct attitudes towards the Cold War), namely the hawkish congressman Pug McCuskey, his cynical bombshell secretary Shirley Defabio, and idealist C.I.A. operative George Hatherly – the latter, I assume, being a nod to Alden Pyle in Graham Greene’s classic novel The Quiet American (which, notoriously, was quite different from the character in 1958’s noirish film adaptation).

Fury: My War Gone By #1

Fury: My War Gone By #1

This arc sets up the series’ themes, most notably the notion that the so-called Cold War was made up of plenty of hot conflicts, with dead bodies piling up all over the Third World as the U.S. embarked in morally and strategically questionable foreign interventions (in this case, supporting French colonialism) in the name of global anti-communism. It also neatly sets up a later arc, with the look on Nick Fury’s bloody face during the climactic battle suggesting his precocious realization that the West doesn’t stand a chance in the region (which of course doesn’t stop him from fighting in Vietnam in the following decade). The ending of issue #3 powerfully conveys that this is a whole new type of warfare with a fiercer enemy than the one in WWII.

Leaving little doubt about the spirit of moral compromise to come, Fury teaches Hatherly ‘the facts of life’ as they literally fight side-by-side with a Nazi.

Fury: My War Gone By #2

Fury: My War Gone By #2

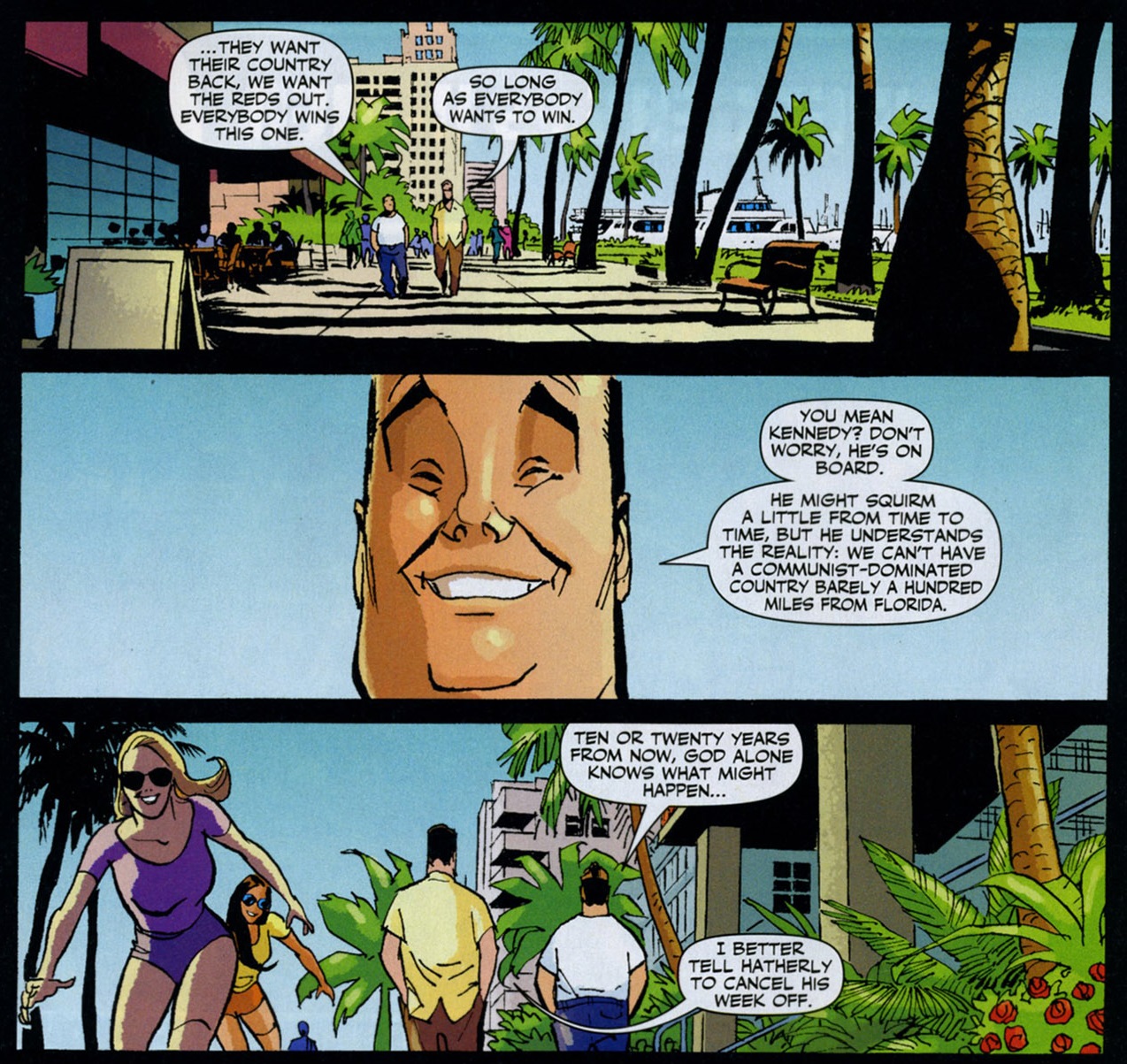

The second arc finds Colonel Fury in 1961, training troops for the Bay of Pigs invasion. If you know this version of Fury, you know he doesn’t like staying away from the battlefield (‘I keep training men I never see again for wars I never fight in.’), which is why he jumps at the chance of heading a secret mission to Cuba. His team arrives there just in time to witness first-hand the C.I.A.’s infamous clusterfuck … (Issue #6, which deals with the operation’s aftermath, is one of the most brutal ones in the whole series.)

We then skip to 1970 Vietnam, where Nick Fury goes on a covert operation with Frank Castle (years before the latter became the Punisher), i.e. the one guy who is just as addicted to combat as him. Garth Ennis has a long history of writing Castle and he has a firm, captivating grip on the character (‘He seems to come from that time in America when things were made just to work.’). Plus, Vietnam war comics are exactly the sort of thing Ennis and Parlov seem born to do (fortunately, they went on to collaborate again in the excellent Punisher: The Platoon).

Fury: My War Gone By #7

Fury: My War Gone By #7

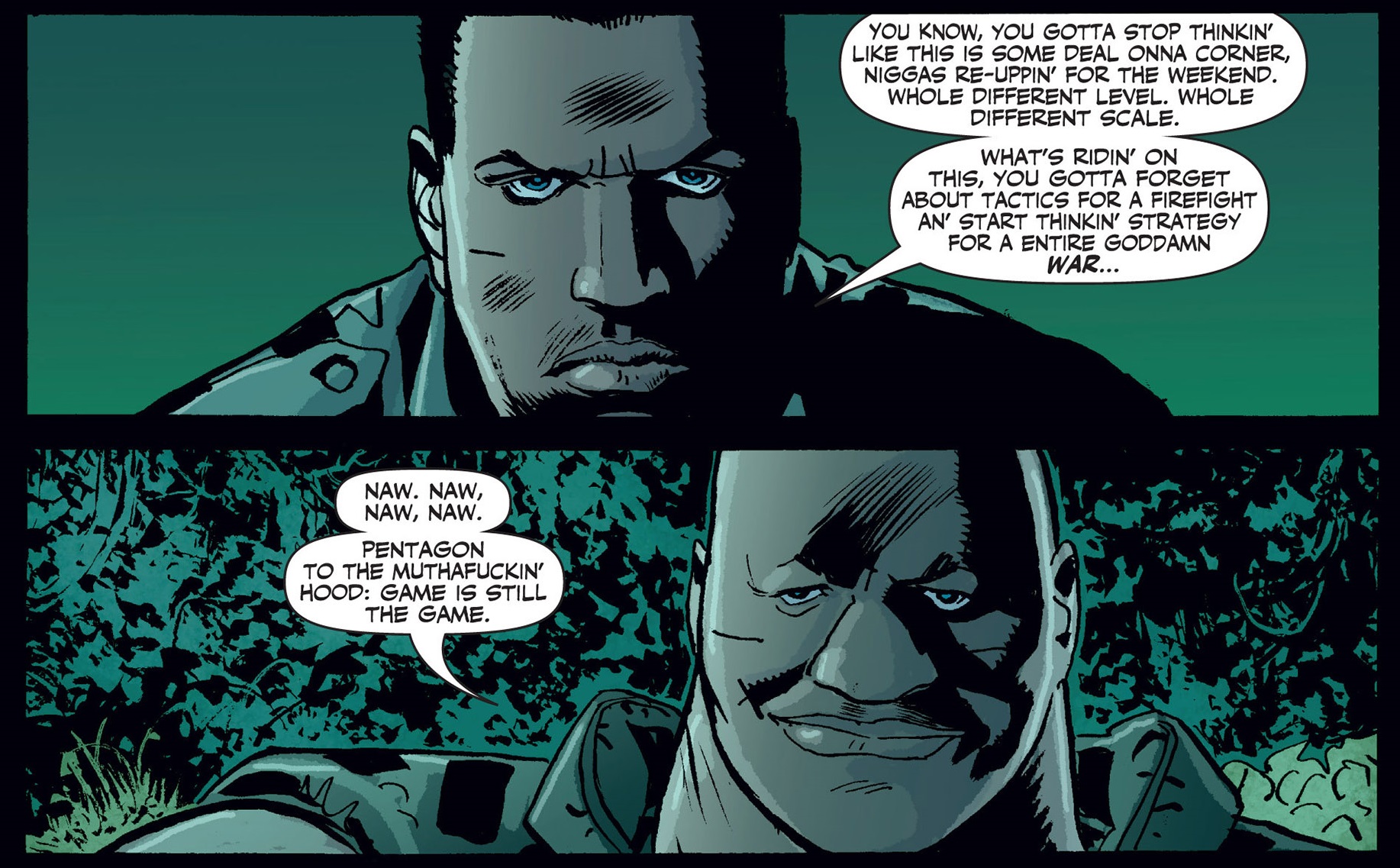

If you don’t count the one-issue epilogue, the final arc takes place in 1984 Nicaragua, where Colonel Fury investigates the charge that the C.I.A. is involved in drug-smuggling in order to fund the Contra rebels against the Sandinistas (besides training them to carry out unspeakable atrocities). This leads Fury to Barracuda, the cunning S.O.B. Ennis and Parlov introduced years earlier in The Punisher MAX and who starred in their spin-off mini-series Punisher Presents: Barracuda (a failed attempt at a Blaxploitation action comedy that isn’t nearly as cool or as fun as the original Blaxploitation action comedies, like Truck Turner or Foxy Brown).

Fury: My War Gone By #11

Fury: My War Gone By #11

It’s hard to deny Barracuda comes across like a particularly outrageous racist stereotype, but his function in My War Gone By is, I suppose, to drive home the point that the line between black ops and organized crime can get increasingly blurry. As one character puts it, Barracuda is the embodiment of the kind of unchecked power that comes with fighting secret wars.

The indictment of the ascent of covert operations is, of course, at the core of the book, along with the idea that some entities – be they the intelligence community, the military-industrial complex, or Fury himself – are willing to find any pretext to carry on fighting. At one point, a Vietnamese general tells the protagonist: ‘Don’t pretend that this is your old war, your European cataclysm wherein Good triumphs over Evil. Be honest: you are here because for Nick Fury, any war will do.’

That is one of many fine passages in a book with a lot of memorable Garth Ennis dialogue, especially between characters who can closely understand and see through each other. Ennis also trusts readers to pick up when the cast betrays their narrow views in light of what we now know about how history panned out…

Fury: My War Gone By #4

Fury: My War Gone By #4

In part, Shirley Defabio steals the show. A force of nature who grows gradually disenchanted with what’s going on, her relationship with Nick Fury starts off as preposterous male fantasy wish fulfillment but gains depth along the way…

Fury: My War Gone By #7

Fury: My War Gone By #7

(This is one of a couple of touching scenes involving Shirley Defabio on a balcony… Perhaps they can be seen as giving a new, retroactive meaning to Nick Fury’s own balcony scenes in the initial Fury MAX mini-series.)

With characterization playing such a central role, My War Gone By gets significant mileage out of sharing some of its cast with other Ennis comics, which is both fan-pleasing and a way to elevate the impact of Nick Fury’s saga by placing it in a large meta-narrative. At the same time, though, the book removes Fury from the even larger meta-narrative of the canonical Marvel Universe, as it outright contradicts the original Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. comics, replacing them as the true past of this version of the character (for one thing, this Fury spent the 1960s-1980s working for the C.I.A., not for S.H.I.E.L.D.).

I have no problem with that, even if I think the gesture takes away some of the edge of the first Fury MAX mini… Much like Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, that series was not meant to present a fully alternative version of its protagonist. Rather, the idea was to build on the contrast with each hero’s campy history by showing us an older, darker, and twisted version of a previously colorful world – much of the fun of DKR and Fury MAX hinges precisely on the notion that this is supposed to be the same Batman who had all those goofy adventures and the same Fury who used all those weird-looking gadgets back in the day. However, in both cases the comics’ success eventually led to prequels that recreated the past, making it more consistent with their new depictions (the Caped Crusader was unluckier than Fury, because he got settled with the dreadful All-Star Batman & Robin, the Boy Wonder). Ironically, introducing more revision reduced the original revisionism.

Regardless, this version of Nick Fury is such a strong character that his memoirs do serve as a great springboard to unleash Garth Ennis’ acidic take on the Cold War.