Last week, I wrote about a 21st century comic that followed the footsteps of novelists like John le Carré and Len Deighton, depicting the world of espionage with downbeat realism and literary sophistication. This week, we’ll look at a very different comic series – one that embodied the spirit of the super-spy boom of the 1960s, when quasi-apocalyptic international tension was converted into colorful adventures and lighthearted intrigue through the kind of films and TV shows later spoofed in Austin Powers (and wonderfully evoked by Guy Ritchie’s The Man from U.N.C.L.E.).

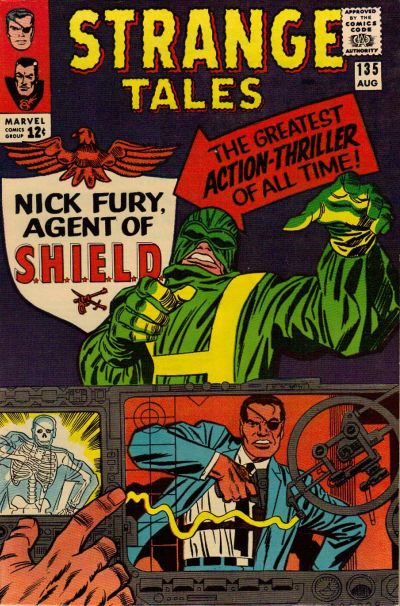

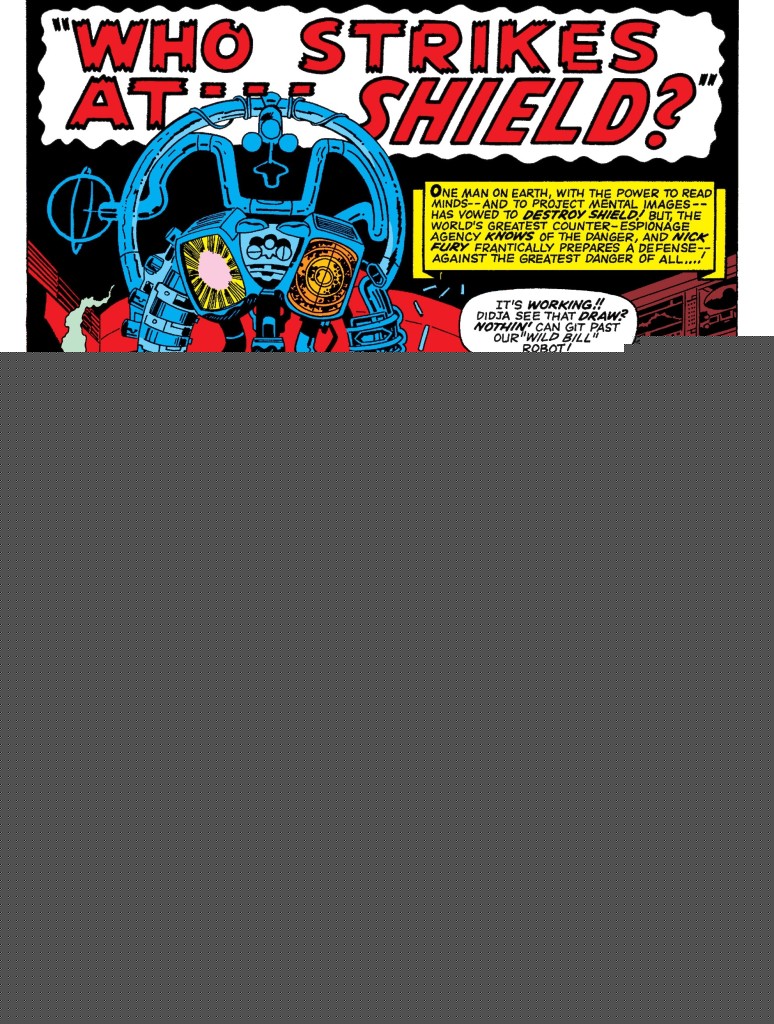

I am talking about the original run of Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D., published by Marvel in the mid-sixties:

Created by the power duo of Jack Kirby and Stan Lee, the cigar-chewing Nick Fury made his debut in 1963 as the star of the war comic Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos. While that series followed Fury’s adventures in WWII, Kirby and Lee simultaneously showed fans what this manly hero – meanwhile promoted to colonel – was up to in the present day. They first reinvented him as a CIA agent in Fantastic Four #21 (a tale oozing with Lee’s hysterical anticommunism, in which Fury sends Mister Fantastic to crush a revolution in South America… and somehow ends up fighting Hitler!) and, in 1965, gave him an ongoing series on the pages of Strange Tales (starting in issue #135), where he became the eyepatch-wearing director of the secret organization S.H.I.E.L.D. (Supreme Headquarters International Espionage Law-Enforcement Division).

A charmingly crude and goofy barrage of gun battles, explosions, and fistfights, the frantically paced Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. made little attempt to hide that what its creators found most appealing in the spy genre was the over-the-top action and the elaborate gadgetry. The first story (‘The Man for the Job!’) was essentially a tour of fun sci-fi contraptions – a Kirby specialty – which became the series’ hallmark, from Fury’s clones (Life Model Decoys, or LMDs) to his flying car, not to mention the Helicarrier (an impressive flying aircraft carrier that housed S.H.I.E.L.D.’s mobile headquarters). That said, you had to wait four more issues before getting a look at the Brainosaur, a special rocket built by Tony Stark (who was a recurring character).

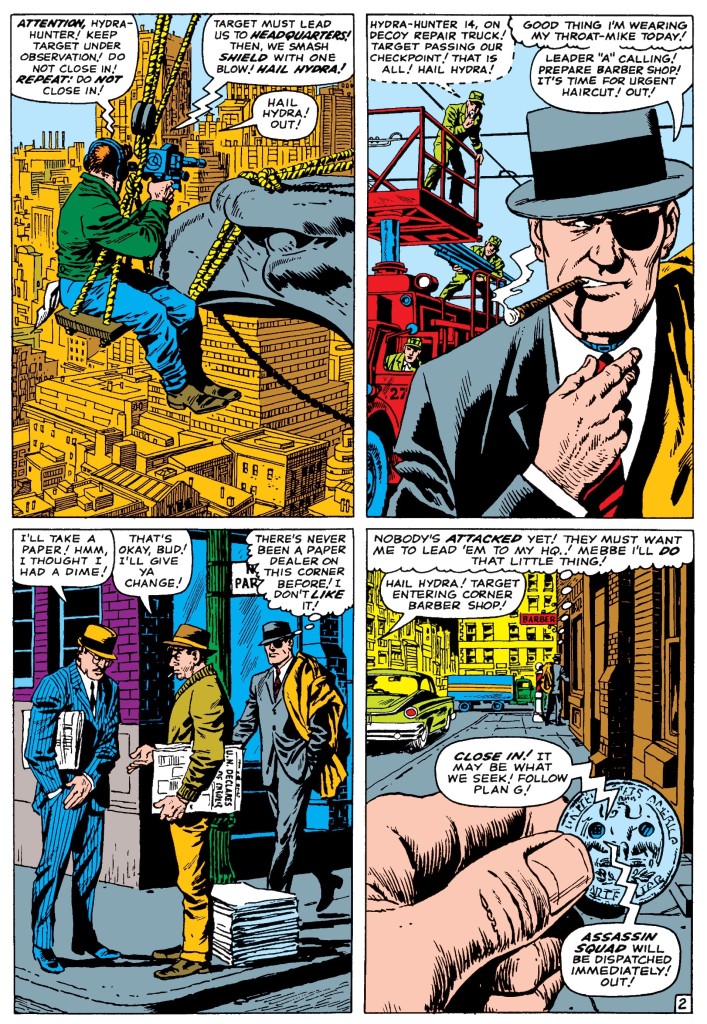

Similarly, the series barely disguised its influences. In issue #137 alone, Colonel Nick Fury visited an in-house inventor who introduced him to clothing items that had been converted into ingenious weapons, an assassin disguised himself as a blind beggar, and there was a kickass set piece on a train followed by one underwater – basically, in a just a few pages, the comic combined variations of scenes from each of the first four James Bond movies!

A few issues later, the credits were especially cheeky about this:

Strange Tales #142

Strange Tales #142

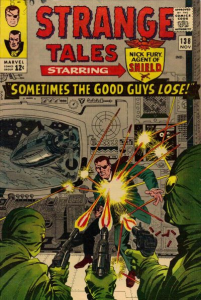

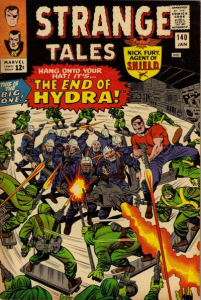

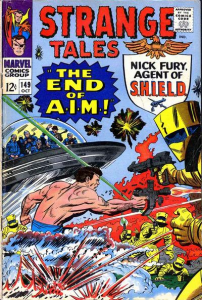

Even though the rumpled, often unshaven, stogie-chomping Nick Fury was notably less suave (and less horny) than Bond, the link to Ian Fleming’s creation was always there, bringing to mind the campiest bits of that franchise – it’s a short leap from Strange Tales #150 to Die Another Day (Fury even faces a villain who hosts a party in a specially-built igloo, on a gigantic floating iceberg). For one thing, like the cinematic 007 – and like The Man from U.N.C.L.E., the other big influence – Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. celebrated détente by electing as the main villain fictitious organizations bent on world domination without an explicit ideology, namely Hydra, Them, Secret Empire, and A.I.M. (Advanced Idea Mechanics). These works thus chose to go for all-out escapism, sidestepping the biggest international rivalry at the time.

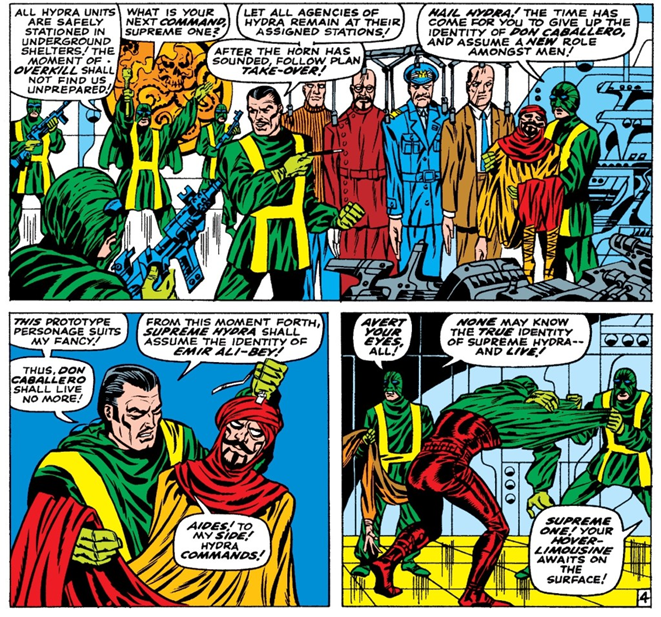

Not that the Cold War zeitgeist was absent from the comic: after all, the paramilitary Hydra, with its totalitarian, depersonalized uniforms and its cry of ‘Cut off a limb, and two more shall take its place!’ can be seen as a Soviet caricature (albeit one Fury could temporarily destroy), despite the fact that the initial leader of this evil organization was secretly in the board of a large western corporation. (The ironic and somewhat touching demise of Hydra’s first leader is a high point in the series.) He was later replaced by someone with an even shiftier identity, hinting that the enemy could be anybody and anywhere:

Strange Tales #152

Strange Tales #152

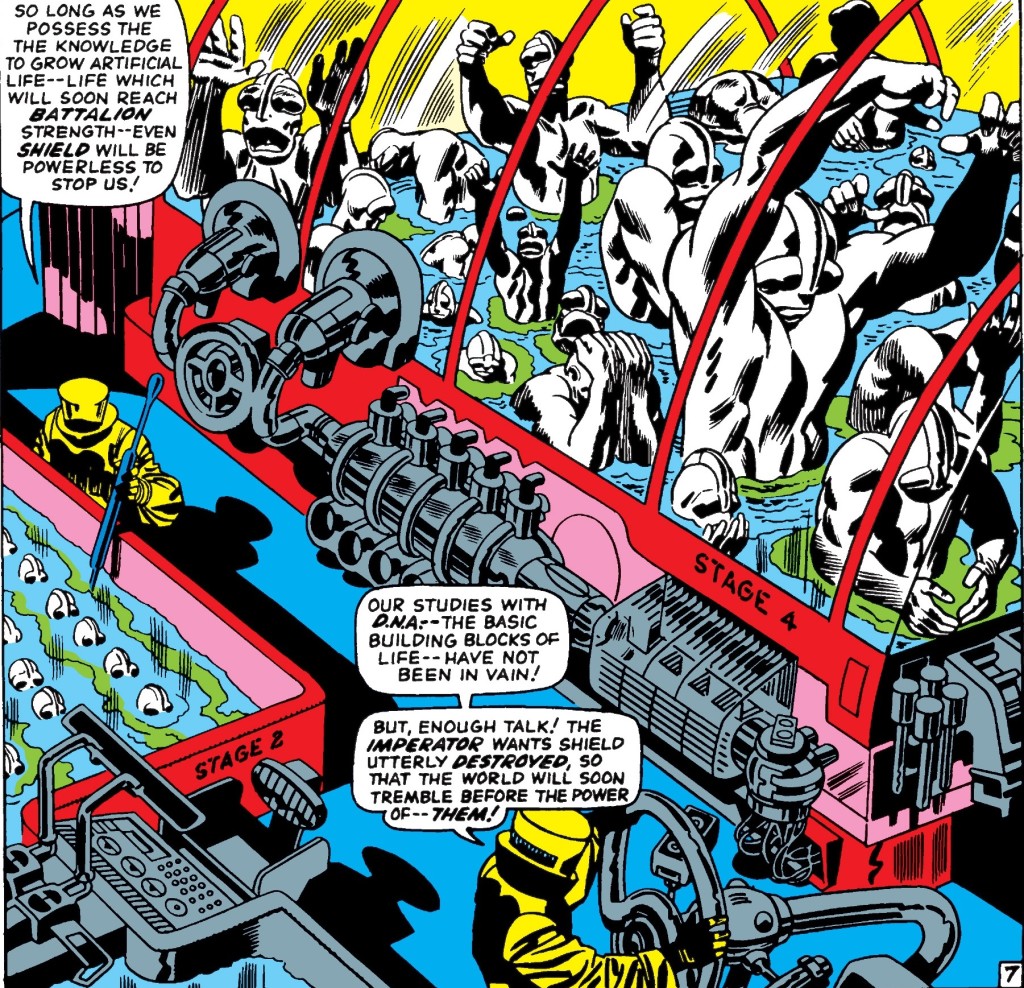

Likewise, Them’s project to grow artificial people (as depicted in a crossover with Tales of Suspense, starring Captain America) feels like nightmarish propaganda about godless commies:

Tales of Suspense #78

Tales of Suspense #78

A.I.M.’s masterplan was as Cold War-ish as it gets – this group tried to influence world leaders by promising a way to bombproof their cities, making them safe from a nuclear attack. Yet, above all, by supplying futuristic technology to terrorists like the Fixer (a genius at building intricate weapons) and the Druid (who combined mystic rites with ‘modern, sinister science’), A.I.M. directly served one of the series’ main purposes, which was to reward fans with one ludicrous mechanical gizmo after another.

Indeed, it makes sense that the villains were mostly concerned with technology since, at the end of the day, technology was pretty much the real star of Nick Fury, a comic where every character was paper-thin and every plot was unabashedly cartoony, so readers’ main draw was to check out what surreal piece of machinery would show up next. This wasn’t even proper science fiction – it was more of a showcase for Kirby’s insane designs (and there sure is nothing wrong with that!) – even though some inventions, like the miniaturized cameras and communication devices, turned out to be quite prescient.

You can tell where Jack Kirby’s heart was, as he mostly drew the tech bits, leaving the rest for other artists: while Nick Fury’s Strange Tales run consistently credited the layouts to Kirby, a host of talented pencillers came in to finish the job. In fact, this combination sometimes worked quite well, like when John Severin juxtaposed his classic, noirish style over Kirby’s outlandish machinery:

Strange Tales #136

Strange Tales #136

One of the pencillers brought in to build on Jack Kirby’s layouts was Jim Steranko, as a trial-run before taking over all of the art duties. This proved to be an inspired move: as discussed next week, Steranko soon elevated this entertaining-yet-clunky Nick Fury comic into the status of masterpiece.