If you read the last post, you know what’s going on. This time around, let’s look at the set of volumes of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen dealing with the last hundred-years-or-so, starting with the bleak Century trilogy.

Century: 1910

Century: 1910

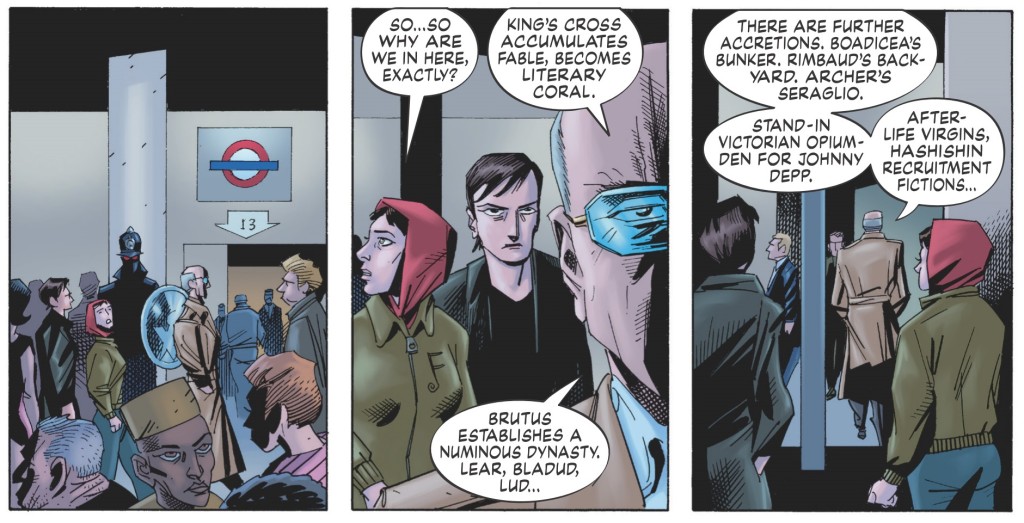

Like with earlier volumes, Century’s overarching plot isn’t that hard to follow, consisting as it does of the League’s (particularly the trio of Mina Murray, Allan Quatermain, and Orlando) attempts to prevent the rise of an antichrist, thus tying up various cult-related works, from Aleister Crowley’s Moonchild to Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby, plus a bunch of Michael Moorcock stories. Suitably, given the diversification of mass culture throughout the twentieth century, LOEG’s pool of allusions became more multimedia, with the series now increasingly pillaging cinema, music, and television. This is not to say that the selection became more mainstream, as it still covered a wide territory, ranging from the hippie exploitation flick Wild in the Streets to the satirical TV show The Thick of It.

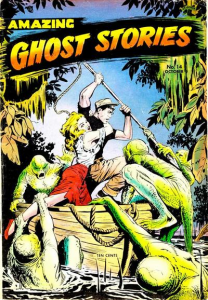

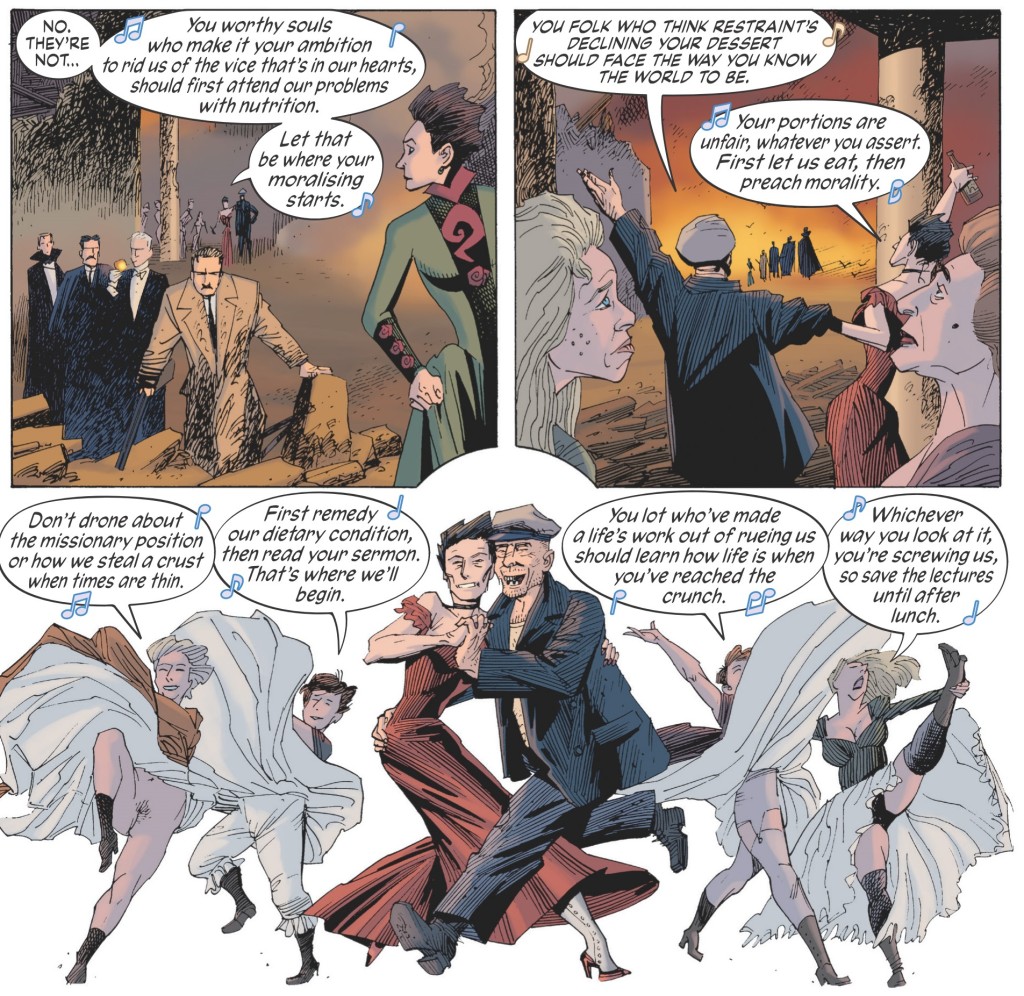

Above all, I suppose it helps to have some vague awareness of at least a few core references: the first installment, set in 1910, mostly riffs on Bertolt Brecht’s and Kurt Weil’s play The Threepenny Opera (the scene above is supposed to be to the tune of ‘The Ballad of Mack the Knife’); the second issue, set in 1969, ties into a couple of British crime movies from that era (the gritty Get Carter and the avant-garde Performance) while recreating the concert from the documentary The Stones in the Park; the conclusion, set in 2009, viciously ravages the Harry Potter franchise. Moreover, because the League – initially still operated by the British secret services, but later under the command of Prospero from the Blazing World – has acquired such an intricate history, the comic becomes quite self-referential, so LOEG’s previous books are pretty much required reading as well.

Century is as much about society and politics as it is about fiction (LOEG’s point is precisely that they all go hand in hand), provocatively painting the twentieth century as a succession of real and imagined horrors piled up on the underprivileged. Alan Moore’s work has always been class-conscious – probably due to the weight of the writer’s own working-class background – even if it tends to veer closer to anarchism (the iconoclastic, deconstructive attitude) and mysticism (the recurring notion that ideas speak through humans) rather than Marxism (a traditional materialist analysis would posit ideas as the result of structural conditions and material contexts, more than the other way around). Yet Century is one of his most upfront comics in this regard. The first issue even finishes with an agitprop ‘musical’ number based on ‘What Keeps Mankind Alive?’

Century: 1910

Century: 1910

(The second issue finishes with a punk-rock version of ‘The Ballad of Immoral Earnings’ called ‘Immoral Earnings (in the U.K.)’ that was actually recorded by The Indelicates!)

Honestly, I see in this move less a reflection of the twentieth century (which had no monopoly on class-based atrocities, especially when compared to the nineteenth century of LOEG’s earlier volumes) than a reaction to the twenty-first. These comics came out between 2009 and 2012, under the shadow of the financial crisis, when some of the Old Left reacted to the rise of identity politics by preaching a return to class-based mobilization (identity issues like race and gender being considered not only divisive in the larger anti-capitalist struggle, but also dubious because younger activists increasingly valued them as intrinsic to individuals rather than criticize them as social constructs). In Jerusalem (part of which must’ve been written around this time), Moore’s alter-ego Alma Warren makes a point of stressing her belief in the primacy of economic status at the hierarchy of social discrimination: ‘Her point is that despite very real continuing abuses born of anti-Semitism, born of racism and sexism and homophobia, there are MPs and leaders who are female, Jewish, black or gay. There are none who are poor. There never have been, and there never will be.’

Not that Moore is a stranger to intersectionality. No matter how problematic you may find LOEG’s use of racialized characters like Fu Manchu and Golliwog, Moore’s body of work has repeatedly conveyed a deep appreciation of how discourse and ideals – including depictions and prejudices – shape the world. (From the same chapter of Jerusalem: ‘As Alma sees things, it’s the metaphors that do all the most serious damage: Jews as rats, or car-thieves as hyenas. Asian countries as a line of dominoes that communist ideas could topple. Workers thinking of themselves as cogs in a machine, creationists imagining existence as a Swiss watch mechanism and then presupposing a white-haired and twinkle-eyed old clockmaker behind it all.’) His renewed emphasis on old-school class politics therefore makes more sense if seen in the context of the current era of the so-called culture wars.

Likewise, in the final issue – 2009 – there is a tinge of nostalgia for past eras (personified by Allan Quatermain) that only makes sense if seen as a frustration with the present, since LOEG’s initial spirit was clearly one of denouncing old-fashioned adventures as having whitewashed Victoriana’s background of poverty, colonialism, and all sorts of conservative values.

Century: 2009

Century: 2009

Moore verges very closely to the stereotype of the cranky old man complaining about kids today. Harry Potter (who literally pisses on Quatermain) is elected as the main target, which can be outrageously funny, but it also comes across as bitter (‘This whole environment seems artificial, as if it’s been constructed out of reassuring imagery from the 1940s…’). As a result, a new set of critics turned against the series – no longer the ones daunted by LOEG’s expansive referentiality, but those who engaged with it and didn’t like what they found beneath the surface, exposing 2009 as the erudite version of a reactionary blogger ranting about how the pop culture he grew up with was better than this generation’s. (One of the most scathing, yet thought-provoking, critiques came from Marc Singer, in Breaking the Frames: Populism and Prestige in Comics Studies.)

There are other ways in which Century spoke to the present through the past. In one of LOEG’s most fanciful bits of reverse-engineering, the prose sections at the end placed the ancestors from characters of the Baltimore-set shows Homicide: Life on the Street and The Wire on the moon, thus linking their genealogy to the Baltimore Gun Club’s space program (from Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon). Moreover, the 2005 bombings in London loomed over the series, from the attack and panic at the climax of 1910 to the many cryptic allusions made by the time-travelling Prisoner of London (from Ian Sinclair’s Slow Chocolate Autopsy).

Century: 2009

Century: 2009

(I actually chose this excerpt because of the reference to From Hell’s insulting film adaptation, further illustrating the sheer amount of deep cuts that are *all over* this comic.)

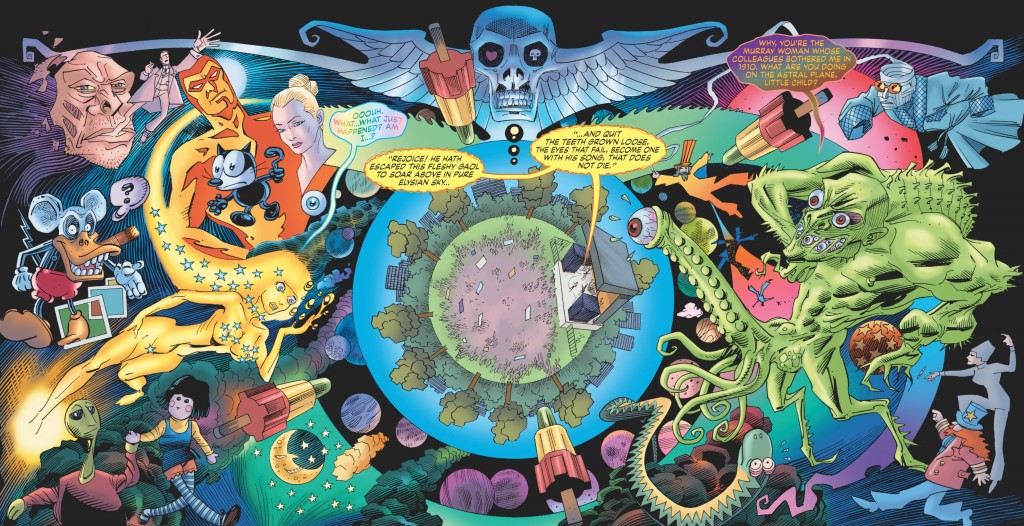

At the end of the day, although mean-spirited, borderline incomprehensible in places, and often making you feel dirty inside, Century is still a pretty entertaining mess. I quite like the way O’Neill and Moore experiment with rhythm by repeatedly syncing the narrative to musical cues (for example, 1969’s trippy climax should be read to the tune of the Rolling Stones’ ‘Sympathy for the Devil’). Also, the artwork continues to be freaking awesome:

Century: 1969

Century: 1969

The following trio of books went back to a more lighthearted style, telling straightforward yarns pitting Captain Nemo’s badass daughter (which Century had established as The Threepenny Opera’s Pirate Jenny) against Queen Ayesha from H. Rider Haggard’s novel She (and from numerous film adaptations, most notably 1935’s atmospheric gothic fantasy produced by Merian C. Cooper) in the 1920s, 1940s, and 1970s. Moore and O’Neill even dialed down the sexual content, at least compared to the ultra-smutty Century.

That said, the references in the Nemo comics are even more idiosyncratic: in Heart of Ice, Charles Foster Kane puts together a team of lesser-known Edisonade adventurers; The Roses of Berlin teams up characters from German expressionistic cinema with the ersatz-Hitler of Charles Chaplin’s The Great Dictator; the climax of River of Ghosts brings together the schlocky anti-Nazi thriller The Boys from Brazil and the goofy Bond spoof Dr. Goldfoot and the Bikini Machine.

My favorite of the lot is The Roses of Berlin, obviously reflecting my own taste as a film buff. It’s not just the geeky fun of watching Captain Nemo go up against Dr. Mabuse, Dr. Caligari, and the robot from Metropolis, but also the awe of seeing Kevin O’Neill and colorist Ben Diagmaliw successfully reinvent themselves once again… If their visuals in 1969 seemed filtered through hallucinogenic drugs and a ‘summer of love’ vibe, here they have the dark, stark brutality of a totalitarian nightmare.

Nemo: The Roses of Berlin

Nemo: The Roses of Berlin

A final word on sex. LOEG has gained a reputation for the way it abundantly sexualizes popular characters and their stories. Indeed, sex is a big part of the series (and, let’s face it, of pretty much all of Alan Moore’s work). As LOEG progressed, sex increasingly dripped from almost every single page in one way or another, to the point of self-parody in Black Dossier and Century… In the former, the framing sequences with Mina Murray and Allan Quatermain on the run involve as much nudity, horniness, and copulation as the dossier’s more explicitly erotic material (like its sequel to Fanny Hill), which I suppose could be seen as a way of illustrating the merging of fiction and reality.

Moreover, those who accuse Moore of overusing sexual violence across his work will surely find themselves vindicated here. LOEG’s debut issue doesn’t last six pages before the first attempted rape and the second issue revolves around a particularly surreal assault (one that is brutally inverted later in the series). Subsequent volumes feature plenty more, with even some of the main cast (men and women) getting attacked at various points, as sexual violence is treated both seriously and humorously (in line with LOEG’s overall darkly comedic tone). To be fair, this isn’t just a trope: the barrage of violence (sexual and otherwise) serves to expose widespread phenomena hidden by – or implicit in – the original stories. Notably, James Bond’s predatory exploits are rendered in a deliberately unpleasant fashion, unsubtly deglamorizing his toxic masculinity.

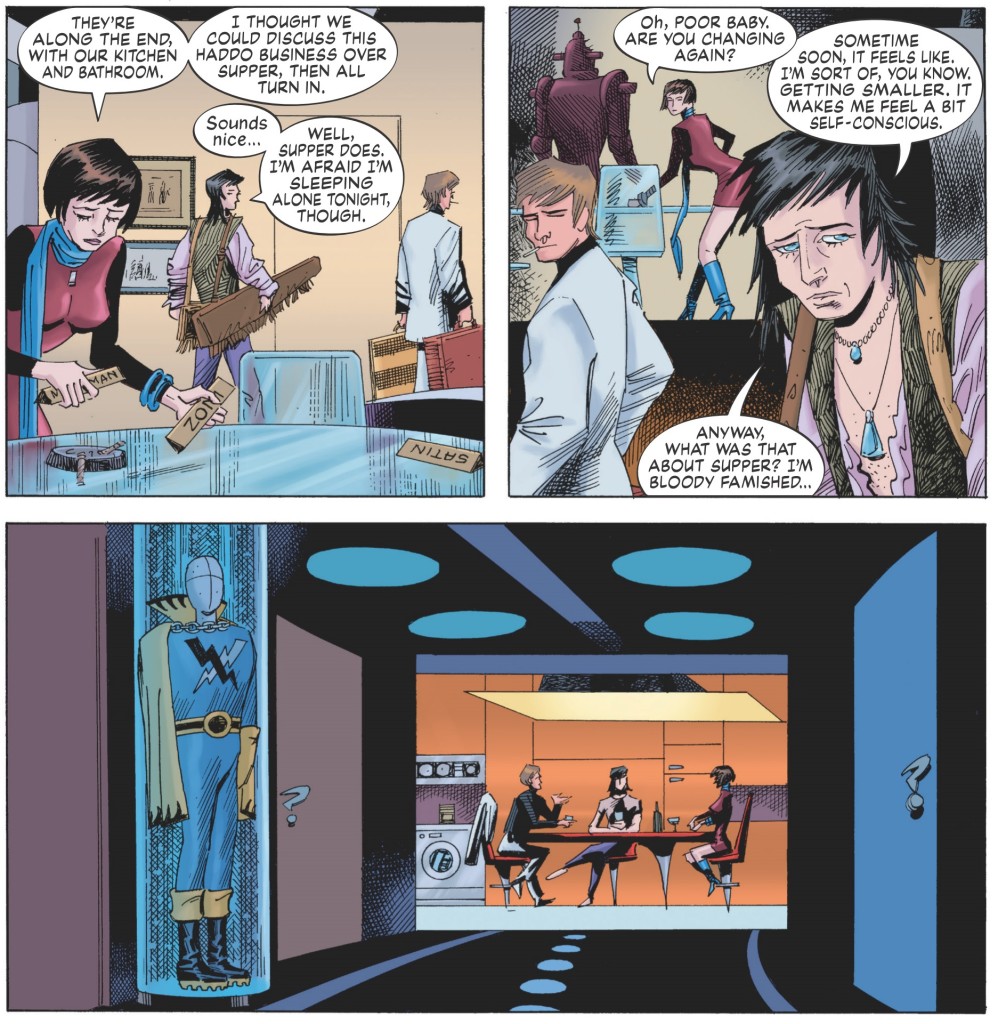

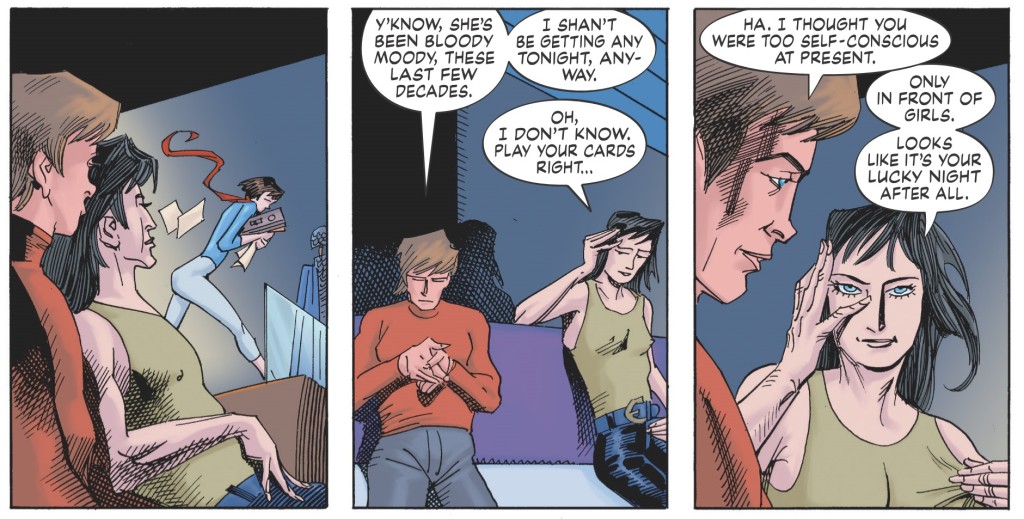

Likewise, the depictions of more benign, pleasurable, and consensual sex aren’t always gratuitous. For instance, they play a central role in the characterization of Mina’s and Allan’s relationship – through sex, we see their initial attraction, lasting passion, and gradual boredom. This is complicated by the sex-changing Orlando, with whom they develop a polyamorous open relationship with a varying gender balance.

Century: 1969

Century: 1969

Interestingly, the different ways each character adjusts to immortality are expressed sexually. For instance, Mina, who tries to keep up with the times, feels increasingly frustrated with Allan, which affects their relationship. In turn, Orlando, who has been basking in immortality for centuries, has settled into it and always feels like having a nice time.

Century: 1969

Century: 1969

Still, other times the lewdness seems more forced. Nemo’s accompanying text pieces are supposedly written by reporter Hildy Johnson (from Howard Hawk’s His Girl Friday) as a lascivious, bisexual alcoholic, which feels quite out-of-character for her.

The truth is that LOEG’s abundant lecherous content doesn’t always seem subordinate to a specific point. Indeed, if I was to look for a larger gesture here, I guess it would be, not necessarily to celebrate sexual liberation in short-sighted terms (as suggested by Eric Berlatsky), but to liberate sex from a fixed meaning: Moore’s attitude seems to be that sex in fiction, like in real life, doesn’t always require a purpose other than itself. In other words, asides from conveying the complex, extensive, and sometimes horrible role of sex in popular culture, perhaps one of the reasons there is so much of it in this comic is also just a sense of raunchy fun.

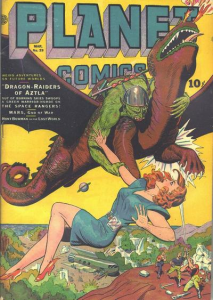

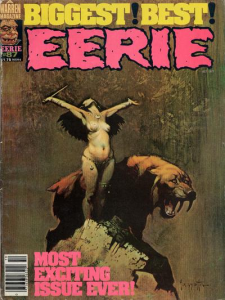

To be fair, titillation (especially via a male gaze) has traditionally been a key component of the kind of pulpy landscape LOEG came to occupy. You can hardly tell the story of the modern sci-fi, fantasy, and adventure genres without acknowledging their lurid predilection for muscled men and big-bosomed women…

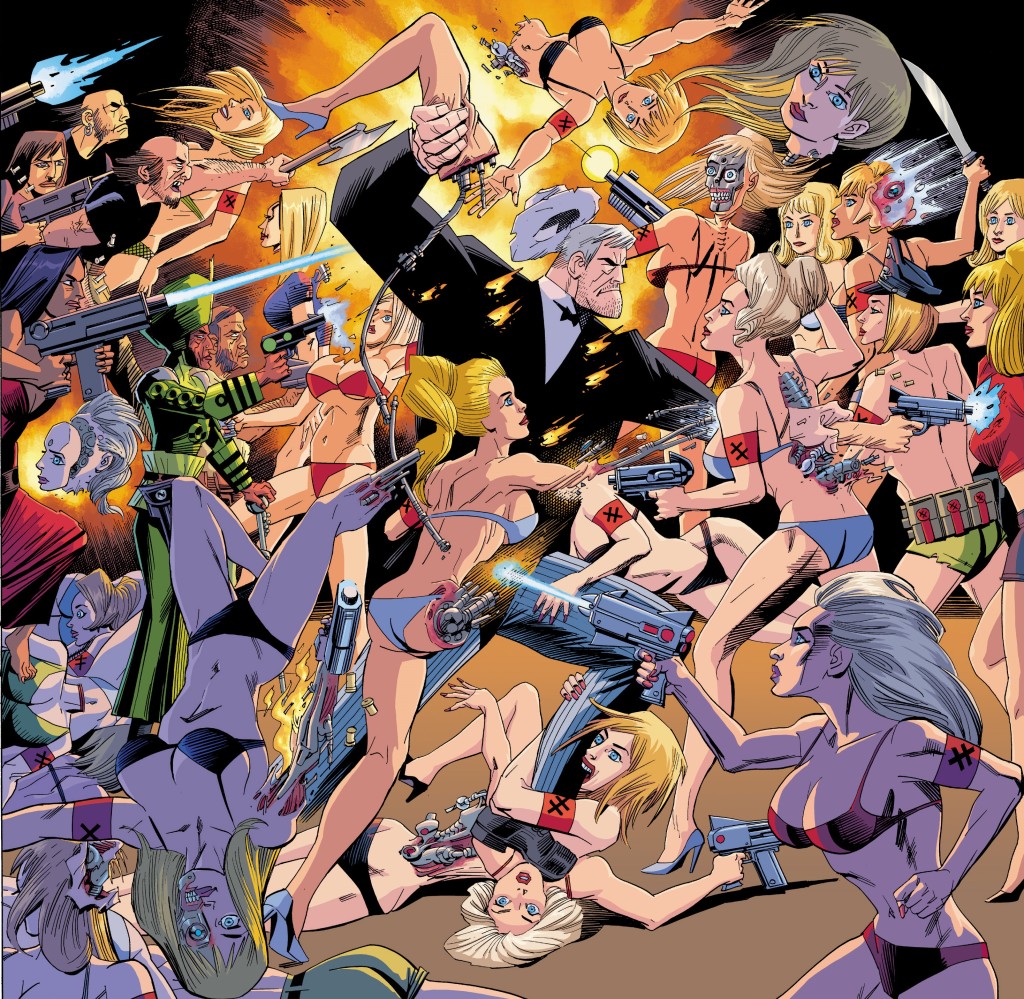

It doesn’t mean you have to emulate it, of course, even if LOEG – for all its revisionism and grotesquerie – has always contained an element of homage, blowing up Alan Moore’s many influences by channeling them through a ludicrously exaggerated style. Ultimately, the series’ perverse glee comes not so much from lowering acclaimed literature to the standards of trashy sexploitation, but from presenting a continuum between the two levels, gradually making it seem natural that an Irish mythological hero would star in what is presumably a tribute to Russ Meyer’s filmography:

Nemo: River of Ghosts

Nemo: River of Ghosts

In a couple of weeks, I’ll discuss how LOEG’s final book brought this fascinating series to an end while living up to its standards of intertextual insanity and ribaldry.