Last week, I mentioned that humor played a key role in Lucky Luke from the very beginning. Today, I want to take a closer look at the types of humor developed in the series’ earliest years…

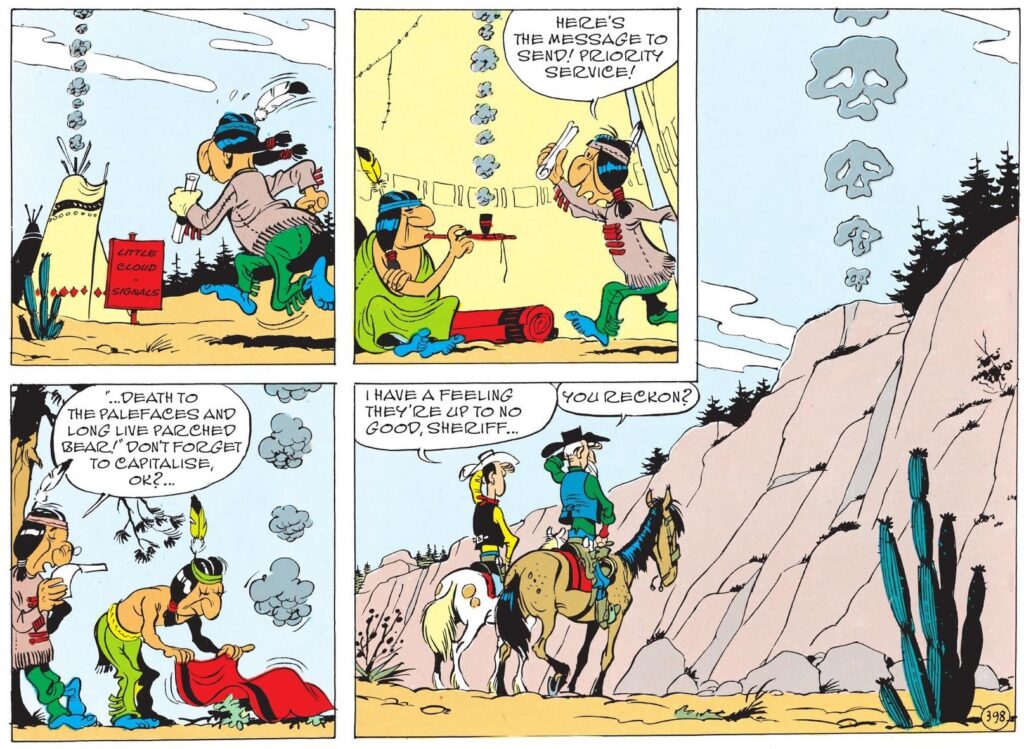

The Bluefeet are Coming!

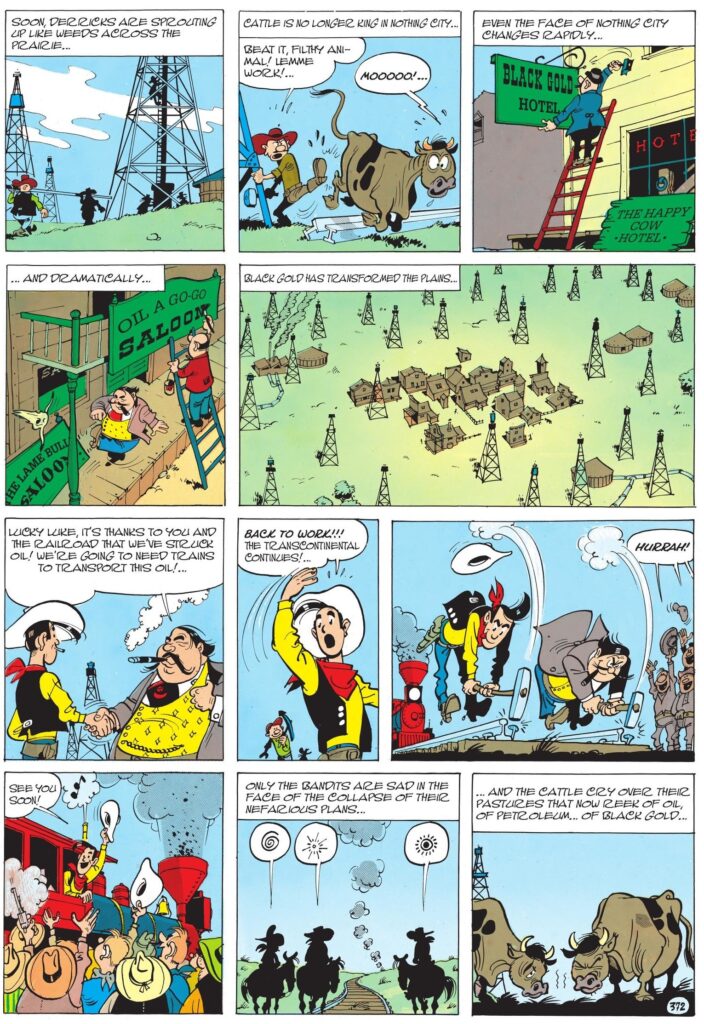

Back when Morris was both writing and drawing Lucky Luke, the comedy was primarily visual, sharing a sensibility with the style of his close friend – and genius – André Franquin.

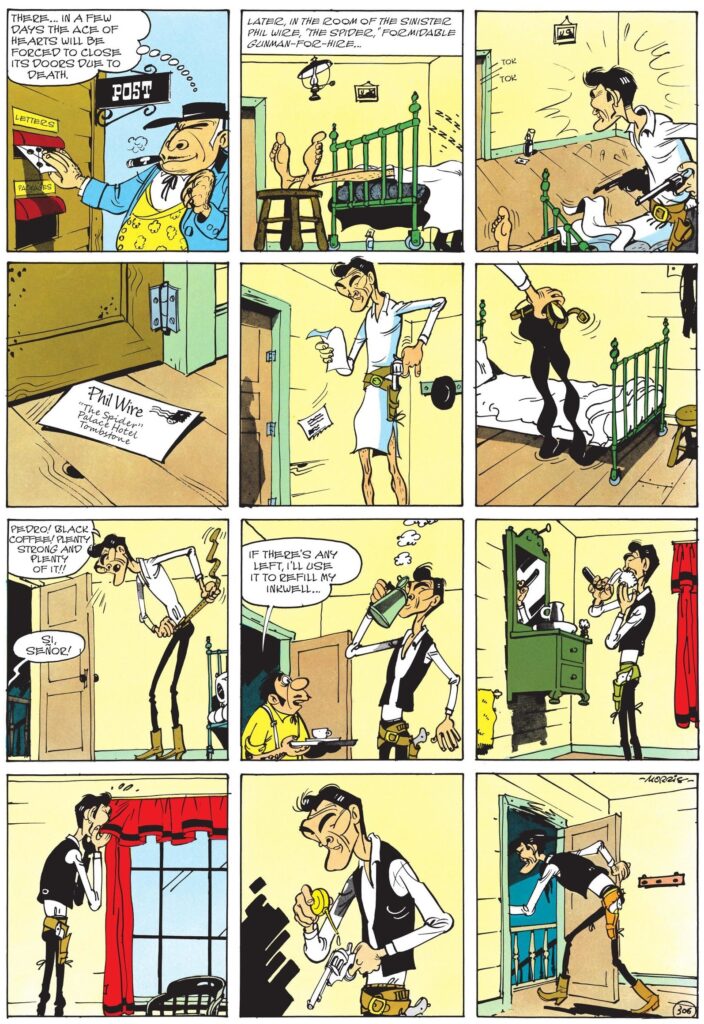

For instance, having struck gold with Pat Poker, Morris built a string of stories around equally colorful villains – and, after the snake-oil salesman Doctor Doxey (a good idea with a mediocre execution), he placed great emphasis in their appearance, making sure that almost every panel with them was funny to look at in some way.

Notably, in the album Phil Wire, not only did Morris module the titular gunslinger to look like Jack Palance in Shane, but he also made him comically tall and had a blast coming up with different ways to showcase this feature:

Lucky Luke and Phil Wire “The Spider”

The chuckles, of course, derive not just from the character’s physiognomy, but also from Morris’ mise-en-scène, constantly framing the action from amusing angles (like when we only see the boots and arm coming out of the stagecoach).

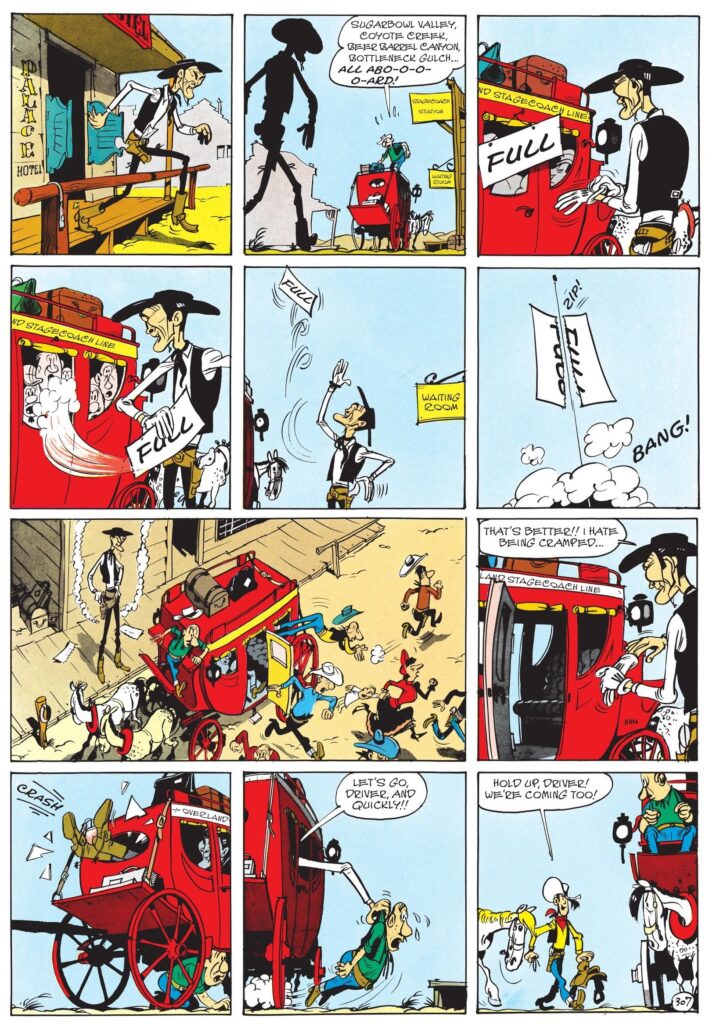

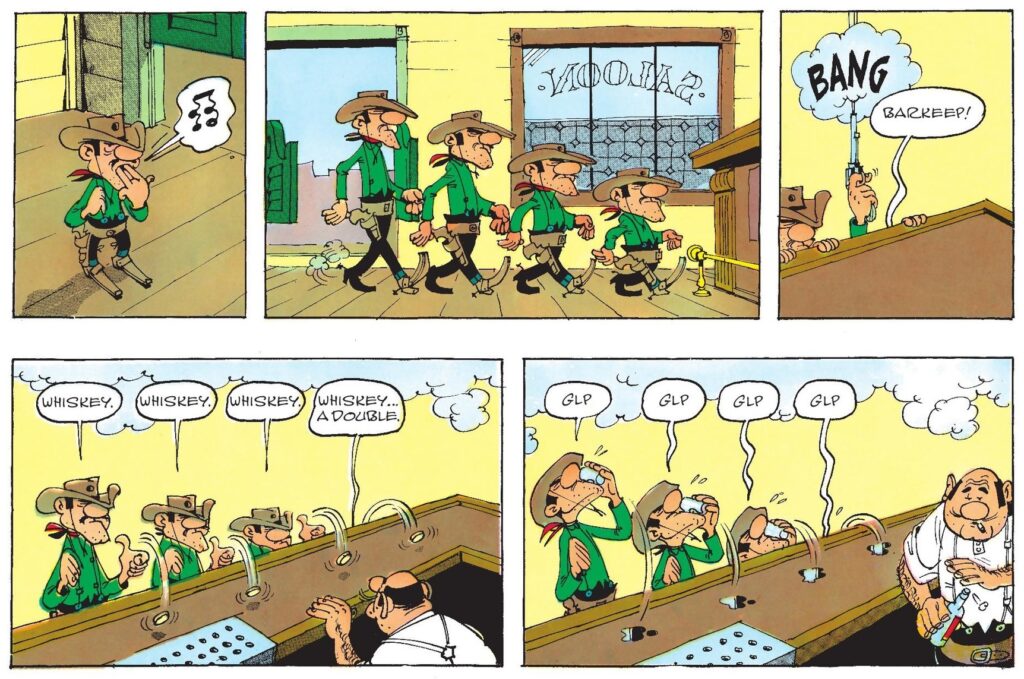

Similarly, in ‘Outlaw,’ besides designing the four Dalton Brothers with descending heights, Morris often had them act in perfect sync and played with the fact that readers could therefore imagine what each of them was doing even when they were outside the frame…

Outlaws

The inclusion of the Daltons was also the first time – of many – when Lucky Luke drew inspiration from real historical figures. This was to become another recurring source of humor: an iconoclastic approach to the icons of the Old West.

Morris’ deconstructive attitude is particularly explicit in ‘Return of the Dalton Brothers,’ a sequel to both ‘Outlaws’ and ‘Desperado City’ where Lucky Luke exposes the lies of a sheriff who can’t stop bragging about his courage and feats (among other things, he claims he’s the one who got the Daltons). Thus, eight years before John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance famously proclaimed ‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,’ Morris irreverently spit in the face of the American propensity for self-mythologization.

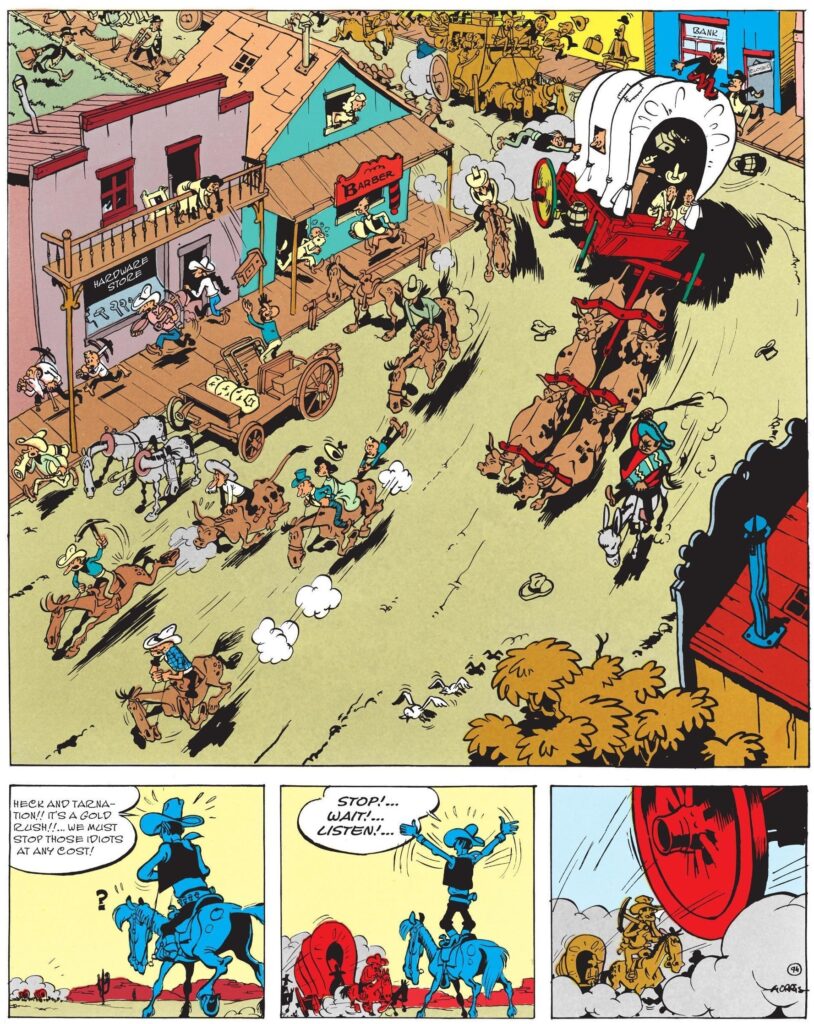

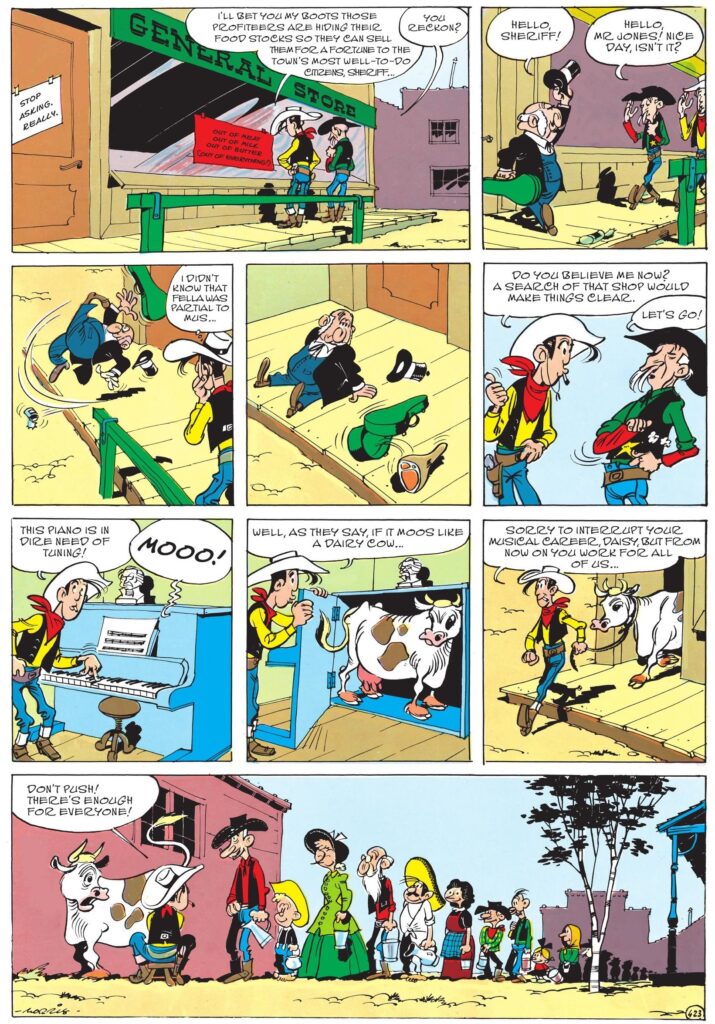

In fact, Morris’ satirical bent had already been displayed in the funniest of his earlier stories, ‘The Buffalo Creek Gold Rush.’ There, Lucky Luke unwittingly starts a rumor that rapidly spirals into an all-out gold rush of maniacally overblown proportions, resulting in a madcap take on greedy capitalism and rampant speculation.

Although the comedy in ‘The Buffalo Creek Gold Rush’ is more situational, it is crucially carried by Morris’ lively drawings, in particular by one of his signature moves: alternating between regular panels (which secure a steady pace) and detailed splashes packed with gags (which convey a general vibe of rollicking chaos).

The Buffalo Creek Gold Rush

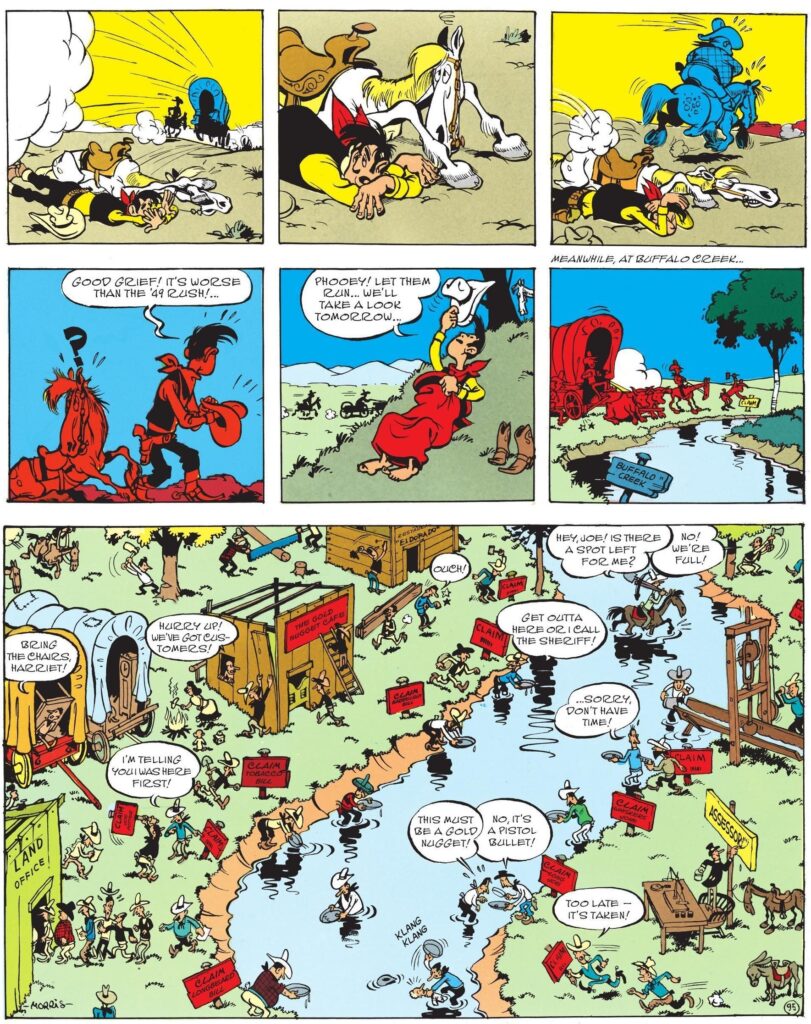

Rails on the Prairie, written by René Goscinny, successfully merges this sort of satire of American modernity with a more direct spoof of Hollywood westerns. Doing for Ford’s The Iron Horse and for Cecil B. DeMille’s Union Pacific the same that Airplane! later did for the Airport movies, the album places Lucky Luke in the middle of the construction of the railroad and has him fight against both natural and human-conceived obstacles, including attacks by Native Americans and sabotage attempts by evil speculators. (In fact, I suspect Brian Donlevy’s performance in Union Pacific had already informed the character of O’Sullivan in Phil Wire.)

By helping out the development of the railroad – and, in later books, of other technologies – Lucky Luke is shown making the USA what it is (or, rather, what it came to represent in popular imagination at home and abroad). Ludicrously speeding up this process or mixing up the chronology, however, makes so-called progress look absurd and grotesque… For example, in a variation of a sequence from Tintin in America, when the rail workers find oil, all the local stockmen immediately switch their trade:

Rails on the Prairie

I mentioned the construction work was attacked by Native Americans, right? Indeed, like the Hollywood westerns and cartoons that inspired Lucky Luke – and like most (American and European) comics at the time – the series contains racialized caricatures of blacks, Asians, Mexicans, and what was then commonly known as ‘Indians,’ with the latter two groups often rendered as bumbling drunks (yep, even more so than the goofy white settlers).

On the one hand, I guess there is a case to be made that Lucky Luke wasn’t meant to relate to reality as much as to the stereotypes about the Old West on the screen (hence the absence of Chinese workers in Rails on the Prairie), which it ultimately mocked. Hell, the series could practically fit into the tradition of Weird West fiction, where the American myths are brazenly warped in a way that acknowledges their unreality. On the other hand, it would be disingenuous to pretend that there was no continuity between such a depiction of violent, superstitious, savage Indians and the ideas used to justify genocide in the United States not that long before.

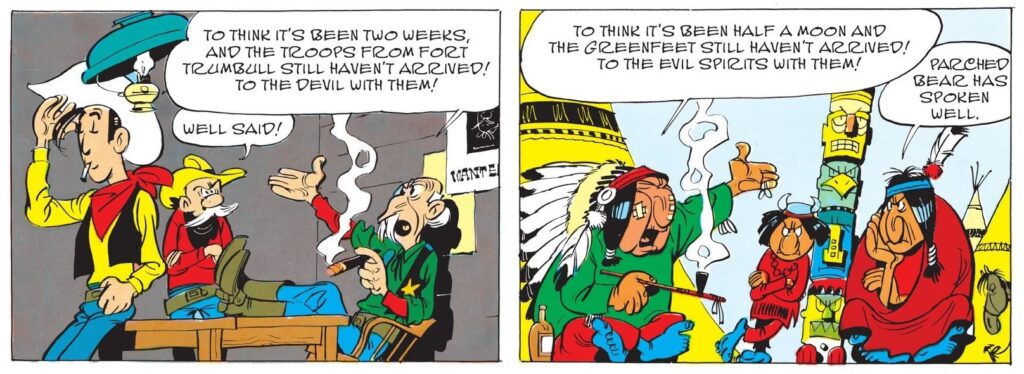

With this in mind, one of the most un-PC albums has got to be The Bluefeet are Coming!, the last album Morris scripted before permanently handing over writing duties to Goscinny. In it, a despicable bucktoothed Mexican, called Pedro Cucaracha (i.e. cockroach), joins forces with the titular (fictitious) tribe, led by the alcoholic Chief Parched Bear, to lay siege on the town of Rattlesnake Valley.

I’ll be honest here: I absolutely adored this book as a kid, not least because it tells one hell of a siege yarn. Even more than Rio Bravo and Seven Samurai, which I only saw later, this is the tale that turned me into an unabashed fan of siege narratives, especially the ones that combine genuine tension with gallows humor…

The Bluefeet are Coming!

As for the ethnic imagery and prejudiced, infantilizing depiction of the villains, it’s not just that I was not aware of the sociopolitical implications… I remember taking it all as just another feature of the series’ distorted world. I expected everyone to be – and look – silly except for Lucky Luke, who was the perennial straight man.

After all, the larger joke was precisely that Luke was a proper hero (i.e. one that could’ve ridden out of a classic western) engaged in proper adventures (i.e. with familiar dramatic stakes) while surrounded by a cast of wacky characters!

The Bluefeet are Coming!

Now, I’m certainly not saying there isn’t anything racist and otherizing about Cucaracha’s physique or the Bluefeets’ broken English (especially once you bear in mind that they’re not supposed to be talking English here, but their own native tongue). Looking at it as an adult, this is quite plain to see!

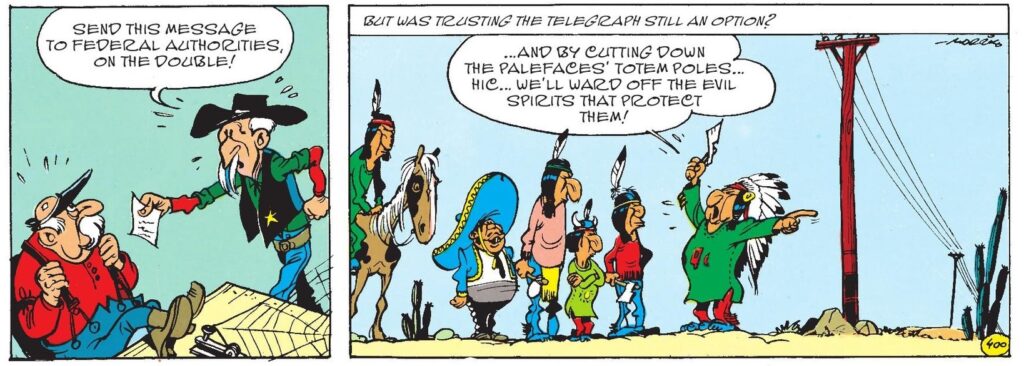

Yet I’d like to point out there is more going on here than a simplistic caricature of difference. Notice the classic gag in the two strips in the middle of the page: although the panels have different sizes, the content has a parallel structure, thus conveying that the characters aren’t so different at the end of the day… and both can be objects and agents (and, in this case, fans) of comedy.

And it’s not just the non-whites that are equalized in this way – so are the cowboys and Indians:

The Bluefeet are Coming!

Rattlesnake’s sheriff is as clumsy and gullible as the Bluefeets’ chief – and in both their communities there are followers as well as sceptics. This is not to say that it feels the same to laugh at the oppressors and at the oppressed… But I do find it striking that, for all the humor based on the notion of difference, there is also plenty of humor subverting the expectation of difference.

Indeed, for every joke about Native Americans being violent (collecting scalps), superstitious (interpreting phenomena through religious lenses), and savage (displaying ‘strange’ customs and a childlike ignorance of ‘civilization’), you’ll find jokes predicated on the twist that they turn out to be harmless, don’t take their culture all that seriously, and engage in recognizable variations of western technology and behavior. Then again, none of this is all that linear: in some of the latter cases, the humor comes from the blatant inaccuracy of what’s being presented (i.e. from the fact that difference is clearly being downplayed), just like the former gags are also ostensibly unrealistic (i.e. the joke there is that difference is clearly being exaggerated).

My point, though, is that, even if not necessarily balanced, Lucky Luke’s humor isn’t unidirectional. Like many other traditional Eurocomics – including, as mentioned before, Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin – the series somehow blends culturally insensitive (written and visual) discourse with a progressive dimension of humanist tolerance and social justice…

The Bluefeet are Coming!