Once again, it’s that time of year when I revisit Eurocomics that marked my childhood, now read through older eyes, and write about some of the dimensions I missed as a kid. Today, I’ll focus on the first decade of the classic run of the comedy western series Lucky Luke written by the French René Goscinny and illustrated by the Belgian Morris, back in the late 1950s and 1960s, when it was originally published in the anthology magazine Le Journal de Spirou.

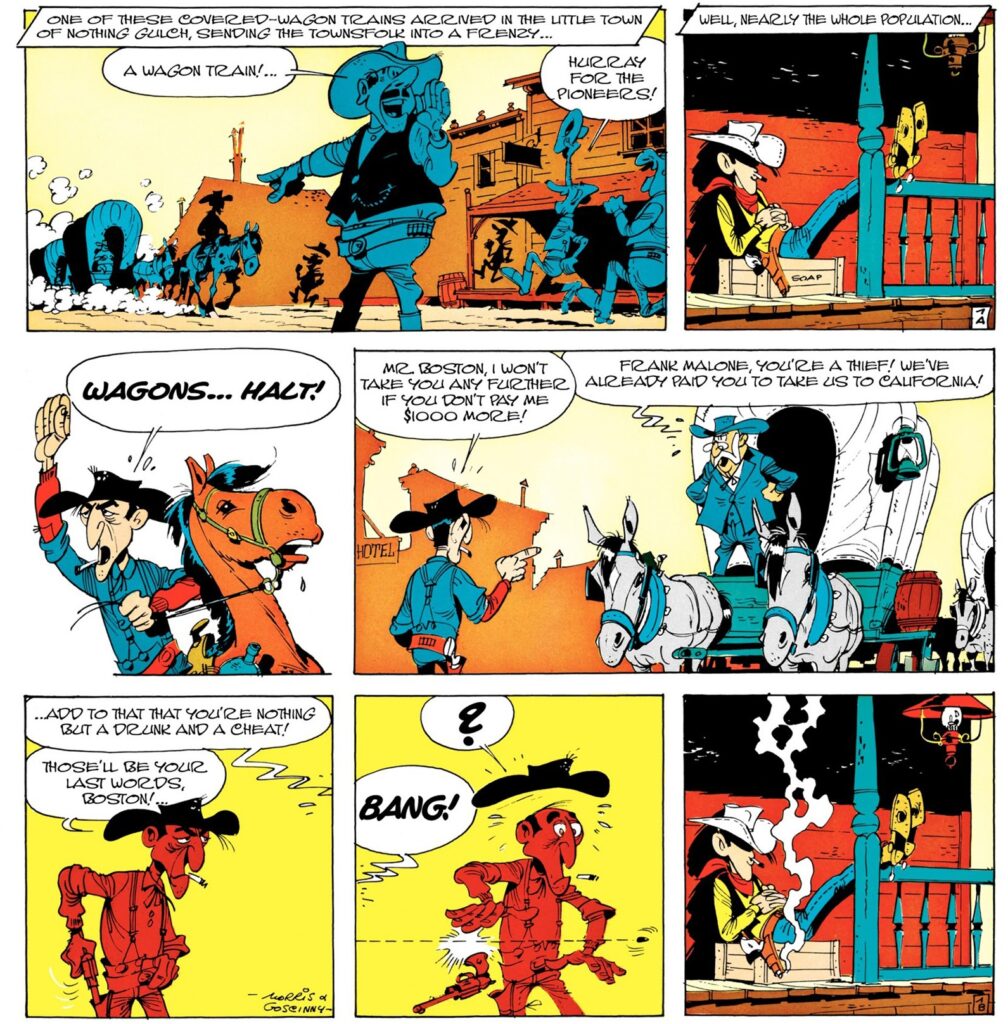

The Wagon Train

Lucky Luke went through a tremendous evolution during this run. René Goscinny’s early collaborations with Morris were still fairly basic in terms of plotting. Joss Jamon’s Gang and The Dalton Cousins are mostly a string of gags pitting Lucky Luke against the titular criminal gangs – the former being a band of renegades from the recent Civil War (including a slimy, spineless Peter Lorre lookalike) and the latter the cousins of the Dalton brothers who had died in a previous album (Outlaws).

The Dalton Cousins

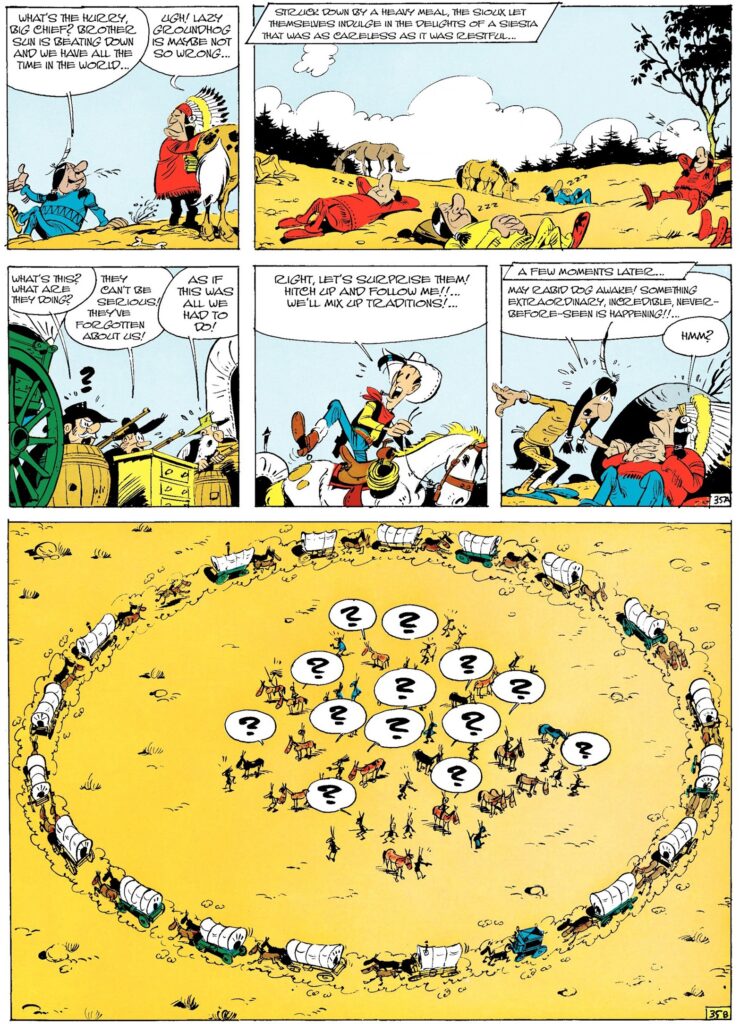

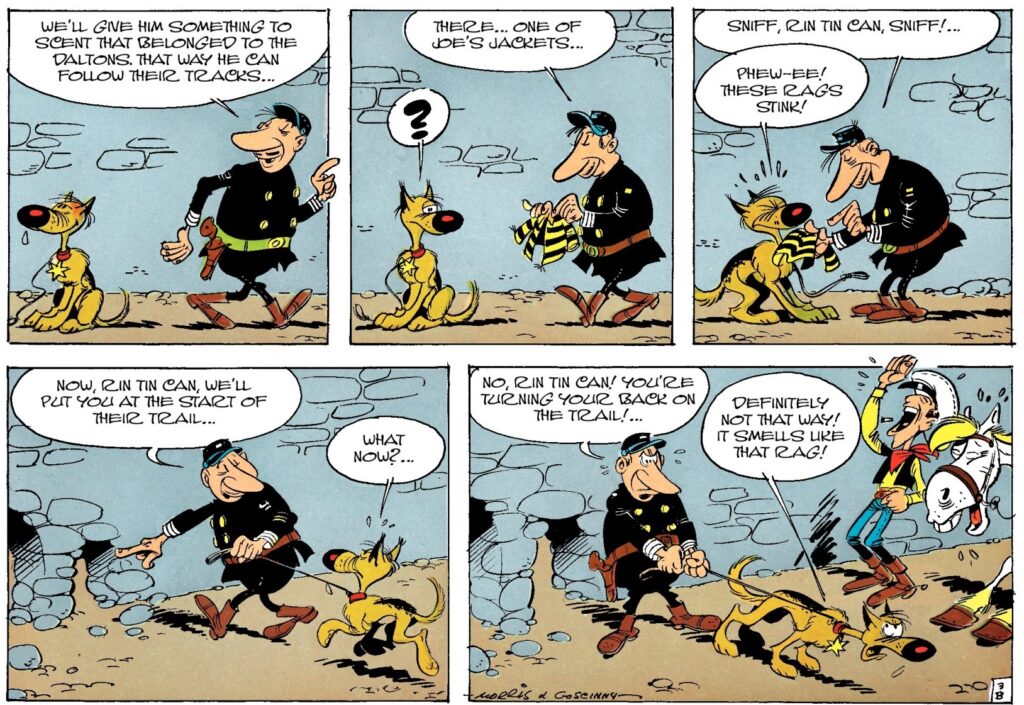

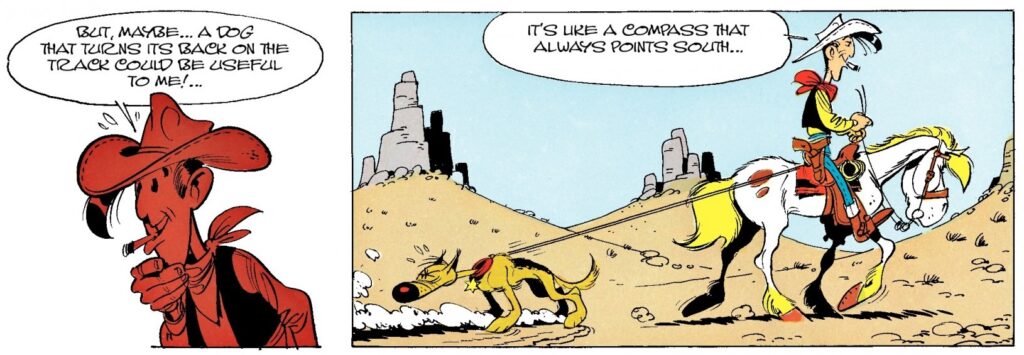

The Daltons would end up becoming the series’ most recurrent villains (hell, other than Luke’s horse Jolly Jumper, they’re by far the most recurrent characters!), soon returning to the spotlight, starting with The Dalton’s Escape and On the Dalton’s Trail. The latter album, in fact, pretty much consolidated a classic dynamic: the Daltons escape from prison (usually in a silly way, since prison security is about as tight as in Arkham Asylum) and are chased by Lucky Luke with the ‘help’ of the prison hound dog Rin-Tin-Can (Rantanplan in the original), the dumbest canine of the West (and a jokey take on the German Shepherd/silent cinema star Rin-Tin-Tin) constantly derided by Jolly Jumper (whose sarcastic thoughts we get to read). Joe, the shortest of the Daltons and their de facto leader, became obsessed with getting revenge on Lucky Luke, and Averell, the tallest one, was not only amusingly thick but also frequently hungry.

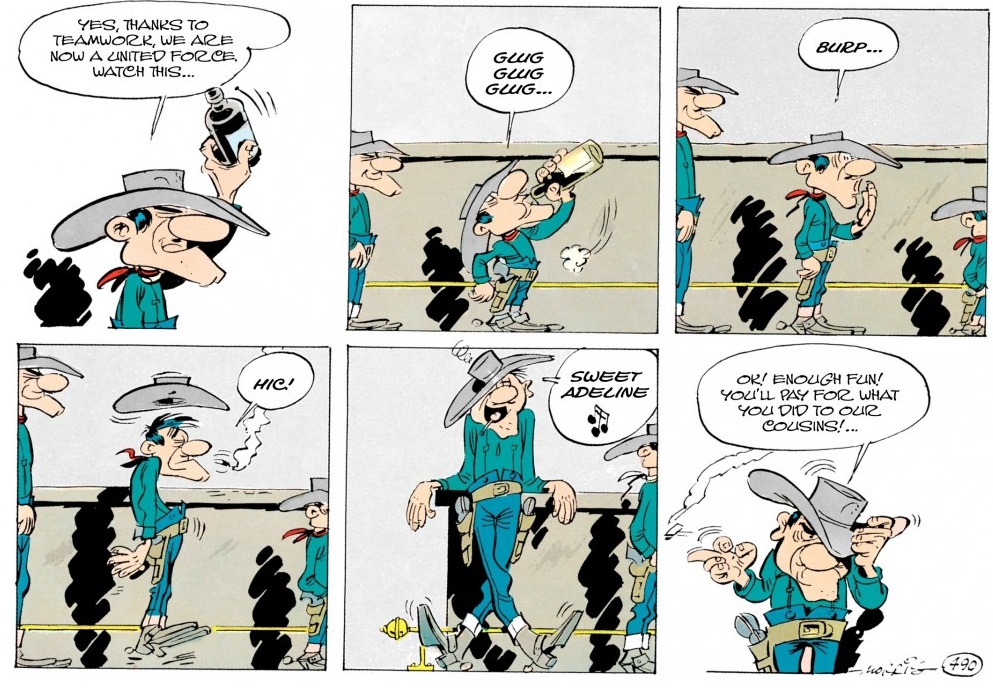

While specific elements only solidified across time, you can tell Goscinny and Morris knew they’d struck gold as early as The Dalton Cousins. They clearly recognized that these four bandits, with ascending heights and ascending stupidity, lent themselves both to broad humor playing on their dumb meanness and to visual gags playing on their physiques:

The Dalton Cousins

Yet it was in the next album, The Judge, that Lucky Luke really found its groove, taking inspiration from real-life – and folk legend – saloon keeper / justice of the peace Roy Bean. Proclaiming himself ‘the Only Law West of the Pecos,’ Roy Bean had become a popular character whose notion of exercising justice largely consisted of extorting money and condemning people to do his chores. For instance, according to Morris’ introduction: ‘An old folk song tells the story of how ‘the judge’ led an investigation when the body of a man killed in an accident was found. Inspecting the corpse in order to identify him, Bean only found a revolver and 41.5 dollars. He seized the gun and fined the dead man $41.5 for possession of a firearm without a licence…’

With such an eccentric character to build on, Goscinny and Morris had a field day turning the courtroom into something out of a W.C. Fields movie:

The Judge

The Judge is an ode to western mythology. Not only does it expand Roy Bean’s legend, but it ends in a sweet note praising the fun generated by folklore figures like him.

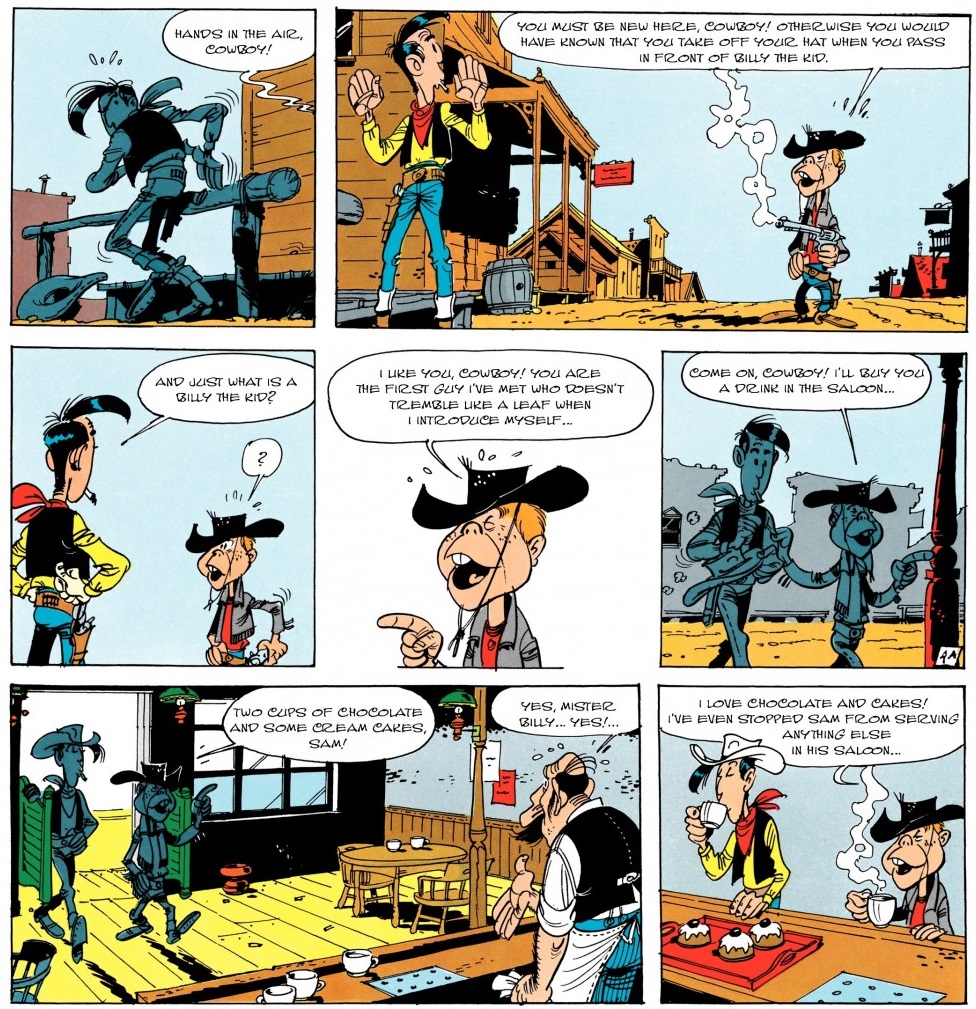

This is more the exception than the rule, though. As much as Morris loved American culture and had grown up idealizing the cowboy lifestyle, he didn’t buy into the romanticization of the Old West myths. If popular culture had a sympathetic take on outlaws like Jesse James and Billy the Kid (while demonizing sheriff Pat Garrett), Lucky Luke set out to ridicule them – and Morris found in Goscinny someone who shared his iconoclasm.

Take Billy the Kid, for instance. Playing with his nickname, the series presented Billy as an actual kid (very quick with the gun but ultimately childish), which led to a spin on The Twilight Zone’s episode ‘It’s a Good Life:’

Billy the Kid

As you can see, Lucky Luke didn’t just take the piss out of the spoiled brat Billy the Kid, but out of the whole subservient town as well. Indeed, the series is a cartoony parody of the whole notion of a country of tough macho men hardened by frontier life: although one of my favorite running gags is how cities always have a badass sign at the entry announcing how deadly they are (‘Stranger, if your intentions are bad, we’ll change your mind… with lead.’), almost all of them turn out to be full of cowards and bumbling fools (it’s essentially the comic book equivalent of Blazing Saddles, albeit with less sex jokes).

One of the albums that takes this to a particularly hilarious extreme is The Daltons Redeem Themselves, where the Daltons get out on parole and find it impossible to go straight because people keep throwing money at them and running away every time they see them! Another one is The Escort, where Lucky Luke has to escort Billy the Kid from Texas to New Mexico for a court hearing, sowing chaos wherever they go because even a handcuffed Billy is enough to scare the crap out of everyone around them…

The Escort is rare in that it is a direct sequel of a previous album. By and large, Goscinny didn’t care about continuity. Lucky Luke’s stories are all self-contained (they always end with Luke riding towards the sunset), follow no chronological order (Luke deals with historical events and figures from the late 19th century, but the sequence is all over the place), and there are practically no recurring characters other than the Daltons (and certainly no character development), so you can pick up almost any album without concern for what happened before. Hell, the early comics contain multiple references to Jesse James and Calamity Jane that do not match those characters’ later appearances at all, but nobody bothers to explain this inconsistency. The whole thing is a slapstick comedy anyway, so it doesn’t take itself too seriously outside of some internal coherence within each book.

Calamity Jane

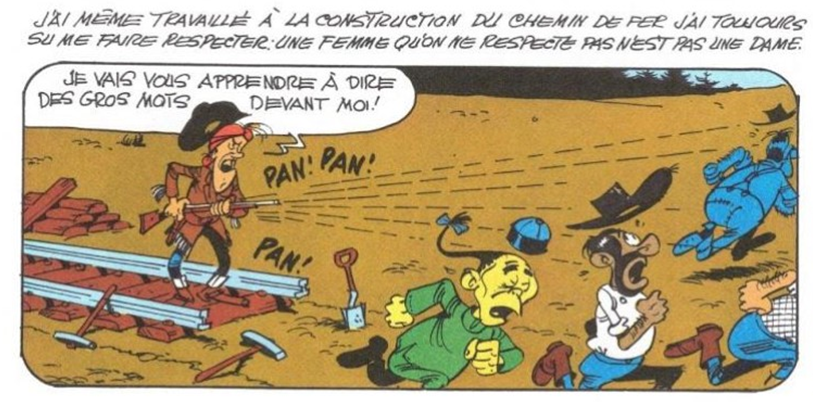

Lucky Luke is much kinder towards Calamity Jane than towards Billy the Kid, perhaps in order to compensate for the series’ very poor track record when it came to female characters. Up until 1966, there were virtually no women in significant roles – and the few women that did show up were confined to traditional stereotypes (a brief moment in The Rivals of Painful Gulch actually suggested that women’s peripheral status helped explain why this West was so ‘wild’ and stupid, positing that women were the marginalized voice of reason in a world of feuding and brawling men).

Calamity Jane is one of the albums I most compulsively reread when growing up – in part because I enjoyed seeing Lucky Luke in detective mode, and in part because Calamity Jane herself was such a charismatic figure. Sure, the central joke is precisely how un-ladylike the titular character behaves, so the humor ends up underscoring the exceptionality of Calamity Jane’s boisterous posture, although the album does treat her with sympathy and respect. I wouldn’t go so far as to call the book feminist, but it’s interesting to note that gender expectations are actually a key theme throughout: besides variety among the female cast, there are also quite different types of masculinity (including an effete gentleman modeled after David Niven who undergoes quite an evolution…), thus both celebrating and laughing at diversity.

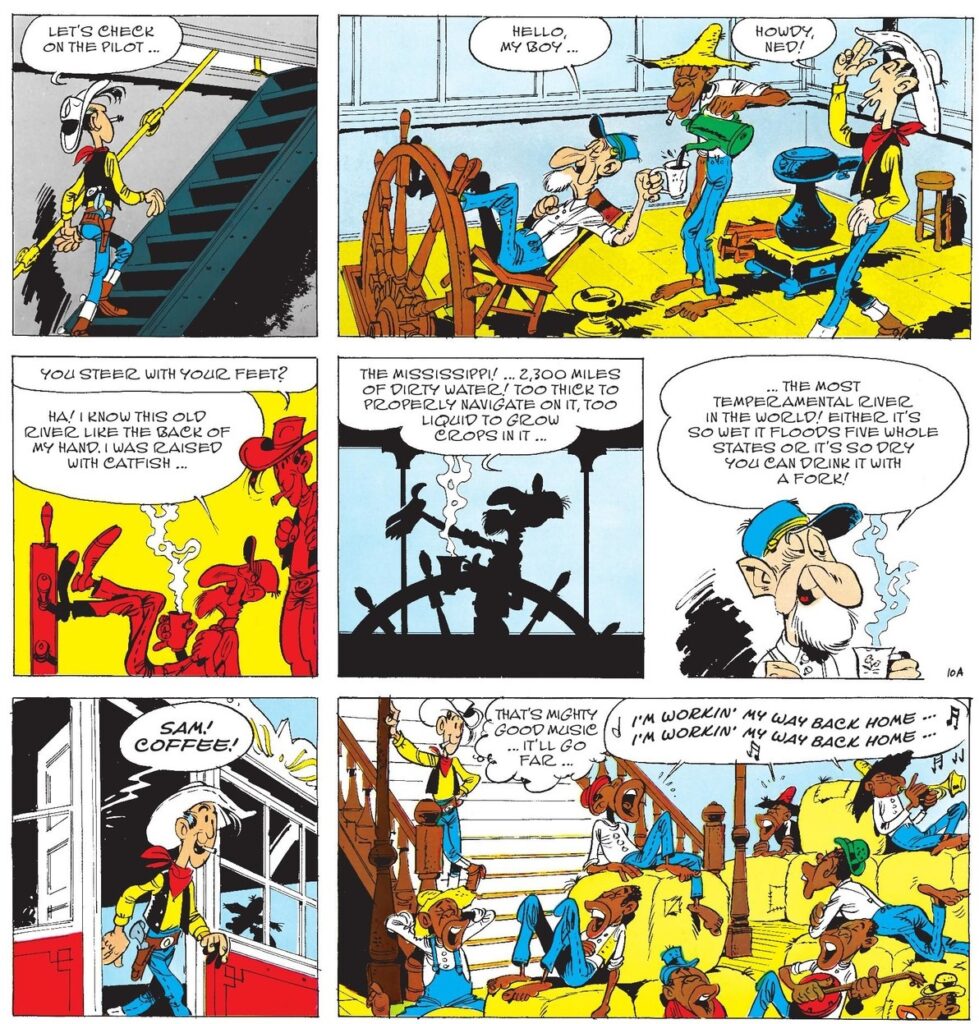

Gender representation is hardly the only non-PC aspect of René Goscinny’s run. For instance, 1961’s Steaming Up the Mississippi (about a race between two steamboats along the titular river) contains plenty of depictions of outrageously lazy, coward, subservient, minstrel-looking black people, including a cheery guy named Sam whose job is to pour coffee to Ned – ‘the best pilot and liar in the Mississippi’ – every time he tells one of his fanciful stories…

Steaming Up the Mississippi

Seen today, certainly much of the sequence on this scan feels cringeworthy, starting with the (depressingly realistic) way Lucky Luke ignores Sam when walking into the cabin. Sure, it’s a European book taking the piss out of American racism (Look! They even have a black guy whose sole purpose is to serve them coffee!) and the low-level workers’ preference for doing as little as possible can be seen as a form of defiance, with the final panel above even conveying a gentle appreciation of African-American musical culture… but it also taps into awkward tropes about laziness and hedonism.

The fine line between mocking stereotypes and reproducing them has given many a headache to the editors at Cinebook, who have been publishing these comics in English (some of them for the very first time). 2021’s edition of Steaming Up the Mississippi opens with an apologetic forward, including this piece of contextualization:

“Neither Morris nor Goscinny could be accused of deliberate racism. Goscinny was Jewish but kept the fact out of the public eye as much as possible. Only 16 years after the end of the Second World War, he was well aware of the danger of racial or ethnic stereotyping, and his use of such clichés was aimed at disarming and ridiculing them. But both he and Morris were still products of the society they lived in, and even the best-intentioned among us, even now, can be strongly opposed to racism and still not realise the egregious nature of some of our actions, words or attitudes – and the harm they can do to those directly affected by them.”

Cinebook’s team have used the freedom of translation to polish some of the roughest edges while avoiding interventions that drastically change the content. In Steaming Up the Mississippi, Sam now calls the pilot ‘Ned’ rather than ‘boss’ (unlike in the original text), suggesting a relation based on a degree of horizontal complicity rather than mere vertical subservience evocative of slavery. Other books use the more respectful term ‘Native Americans’ when translating the French equivalent of ‘redskins’ (although preserving the constant references to their notoriously low tolerance to alcohol). And if you compare the coloring of Calamity Jane with the one in the French edition (at least with the album I got, which has a few decades), you’ll notice a Chinese character’s skin was originally rendered in a much more dehumanizing bright yellow:

Calamity Jane (French edition)

To be fair, while such terms, stereotypes, and artwork may sound insensitive today, in Lucky Luke they don’t seem informed by malice. These albums are unabashedly cheerful, taking recognizable tropes and exaggerating them to comically outlandish proportions.

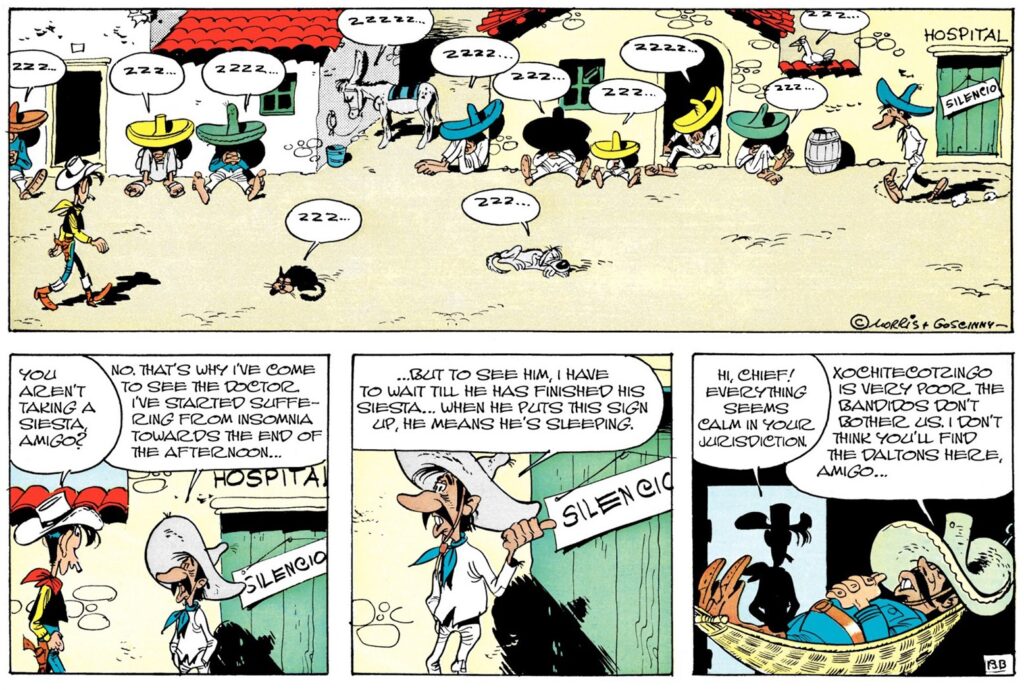

In Tortillas for the Daltons, nobody is goofier than the North-American Daltons and Rin-Tin-Can, but the comic also has its fun with broad caricatures of the Mexican as poor, siesta-loving, easygoing peasants:

Tortillas for the Daltons

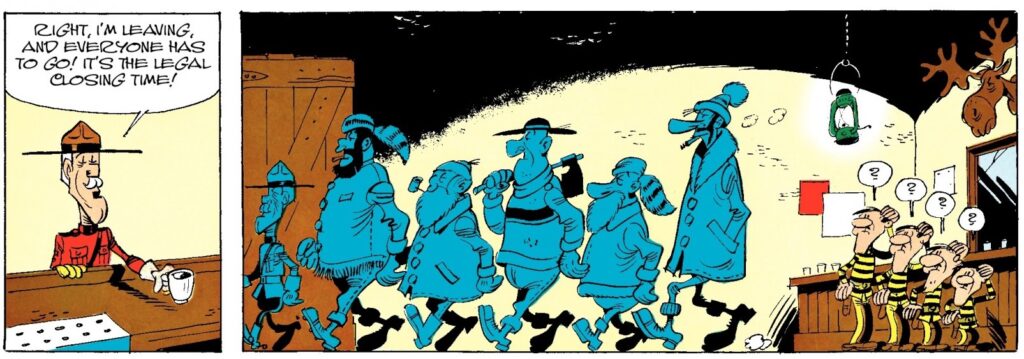

Other albums did the same with the humble, quaint-speaking Chinese launderers…

The 20th Cavalry

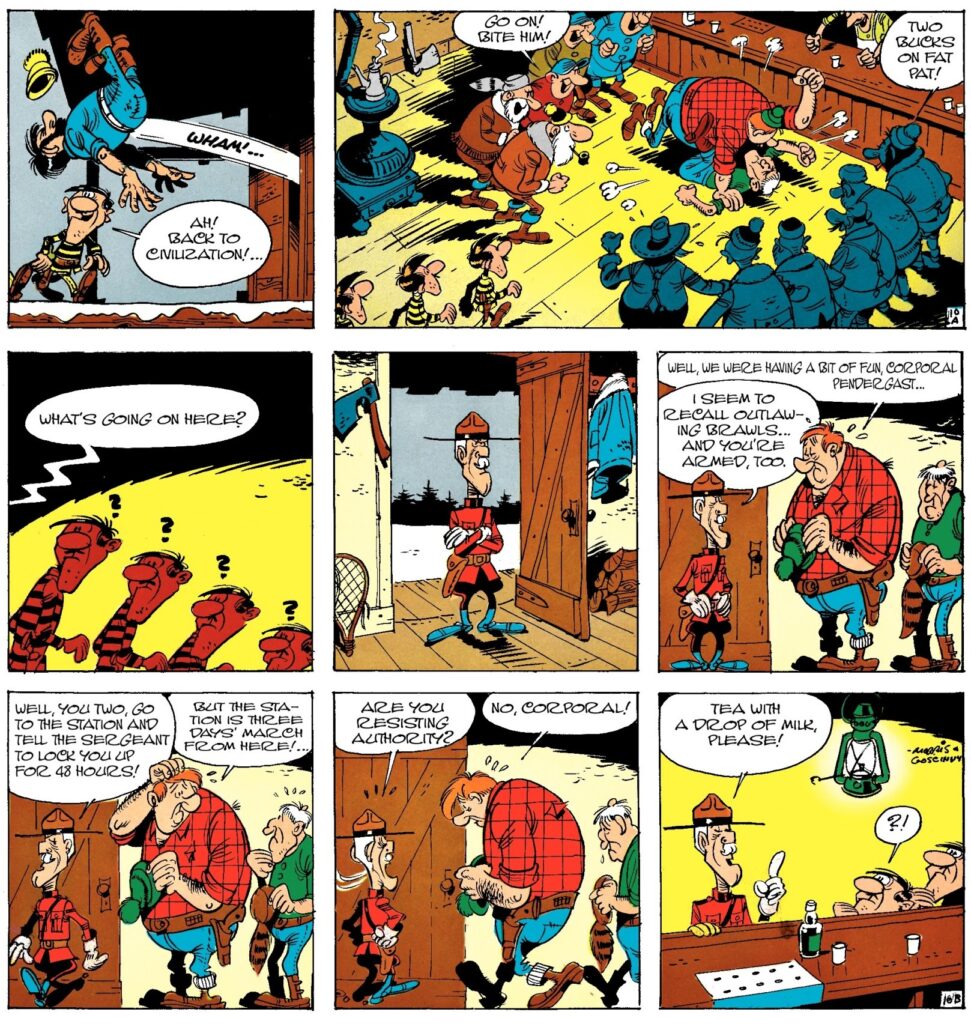

…and even with the polite, authority-respecting Canadians…

The Daltons in the Blizzard

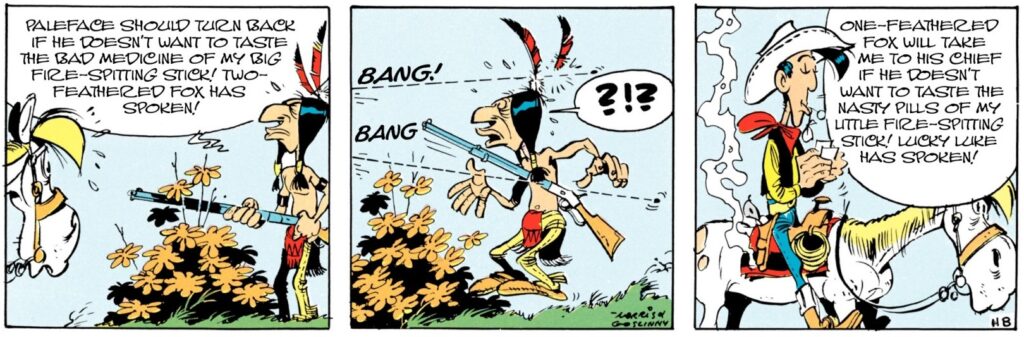

…not to mention, unsurprisingly, with all kinds of Native Americans, including their allusive names and a vocabulary that often required lengthy descriptions of new objects for which they didn’t previously have a simple term:

The 20th Cavalry

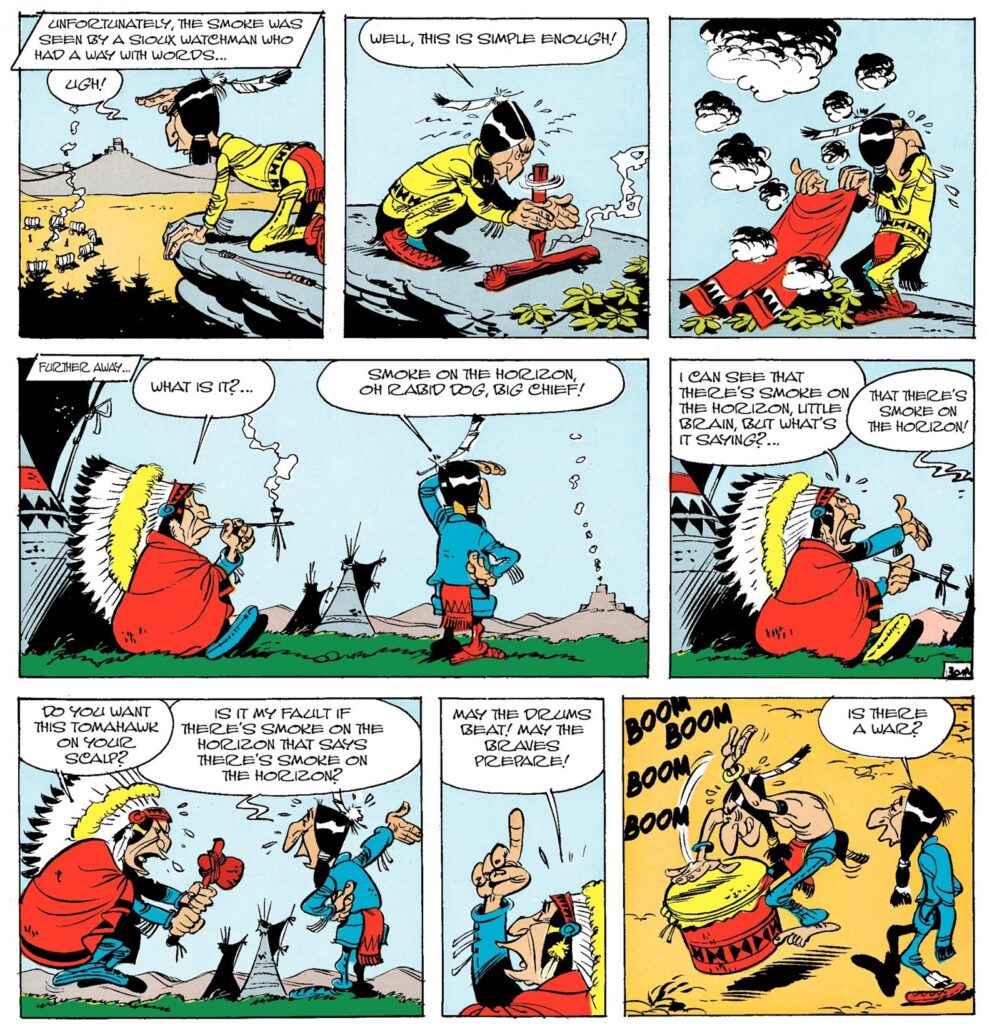

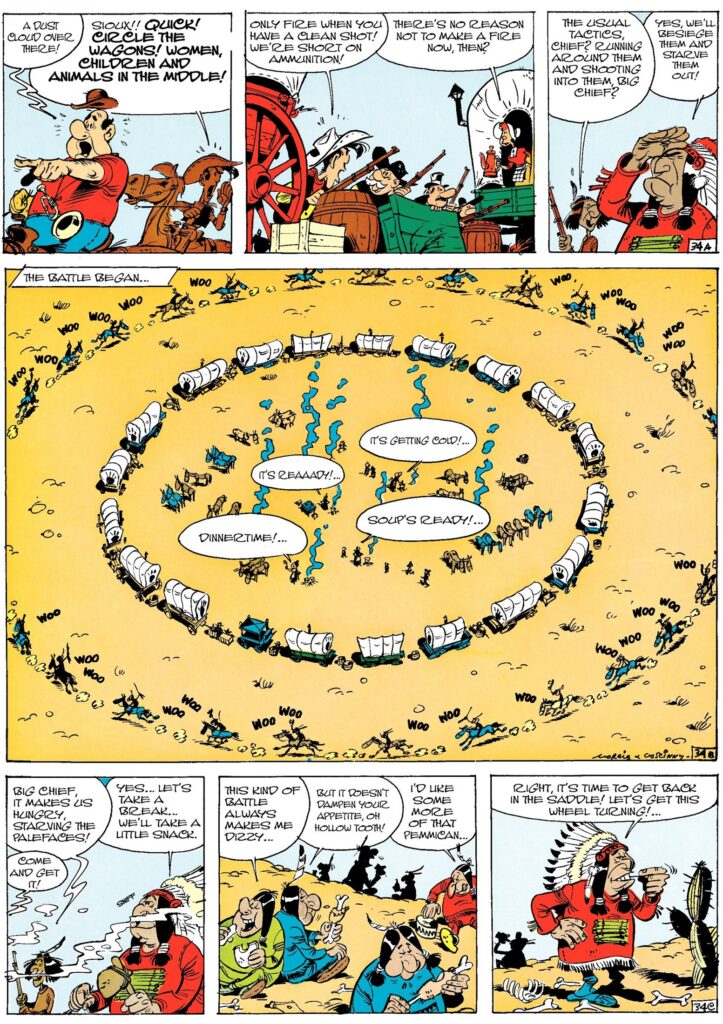

When it came to the Sioux, the joke was not just to exaggerate their reputation for war (the chief is obsessed with scalps), but also to defang their feared image by presenting each tribe member as a bit of a klutz:

The Wagon Train

The latter gesture culminates in a great sequence that pushes humorous inversion to the next level. The 1964 album The Wagon Train revisits a classic setup, with the Sioux surrounding and attacking a caravan of settlers that rearranges itself into a protective circle. Rather than a scary or dramatic confrontation, however, the book plays the whole thing for laughs as various characters outright refuse to act the part expected of them in traditional narratives…

The Wagon Train

Indeed, if Cinebook decided to publish these albums regardless of their objectionable and possibly upsetting caricatures, it’s probably because of an appreciation for the fact that they are nevertheless outstanding comics in terms of craft… and, often, pretty darn funny.

What made Steaming Up the Mississippi one of my favorite albums as a kid wasn’t the racial dimension but rather Ned’s riotous descriptions of the Mississippi and all the exciting obstacles Lucky Luke had to face in the boat race, from saboteurs to outlandishly sudden floods and droughts (‘The Mississippi’s one fickle old man… One time I saw it rise, then fall so quickly that the fish stayed up in the air before falling and cracking their skulls on the dry riverbed…’).

Heck, for all the outdated stereotypes and occasional forays into black humor, there is still something relatively wholesome about Lucky Luke in the 1950s and ‘60s. Goscinny’s run mocks vices like gambling, brawling, and excessive alcohol consumption while often presenting schools as the ultimate sign of progress.

Crucially, Lucky Luke himself is consistently framed as a somewhat classic, un-deconstructed hero, defending visionaries and/or underdogs. He’s pretty much a straightforward embodiment of the archetype of the brave, lonesome, laconic drifter (even if he occasionally carries out missions for the government).

And yet, he’s not the brooding type. Rather, Luke often seems to be enjoying himself, especially when dealing with Rin-Tin-Can…

The Daltons in the Blizzard

Yep, it’s a far cry from the cynical, gritty anti-heroes of revisionist takes on the genre…

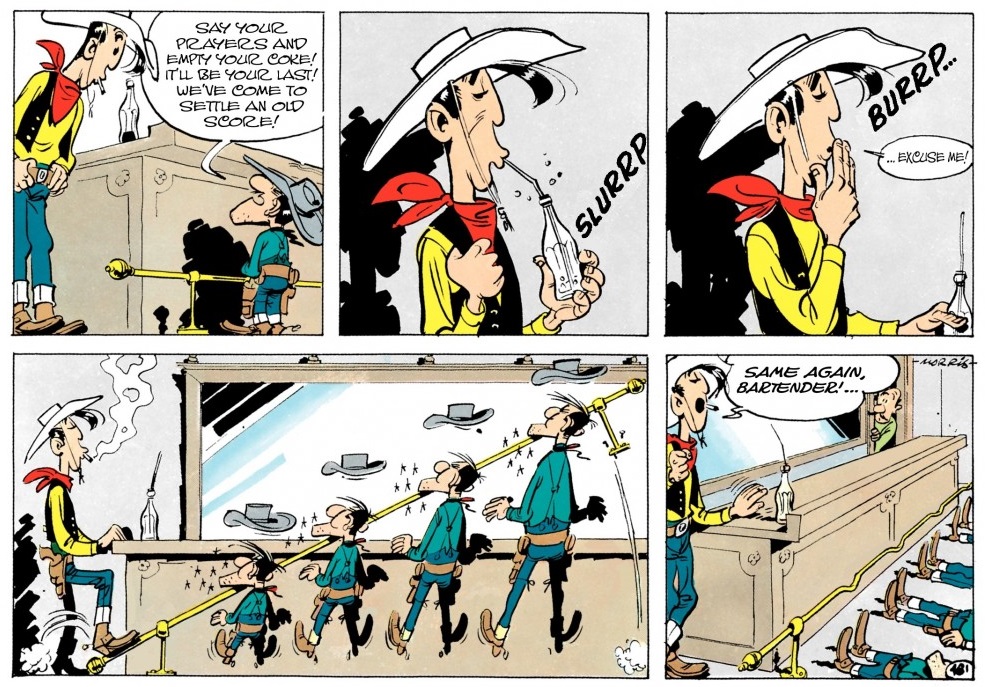

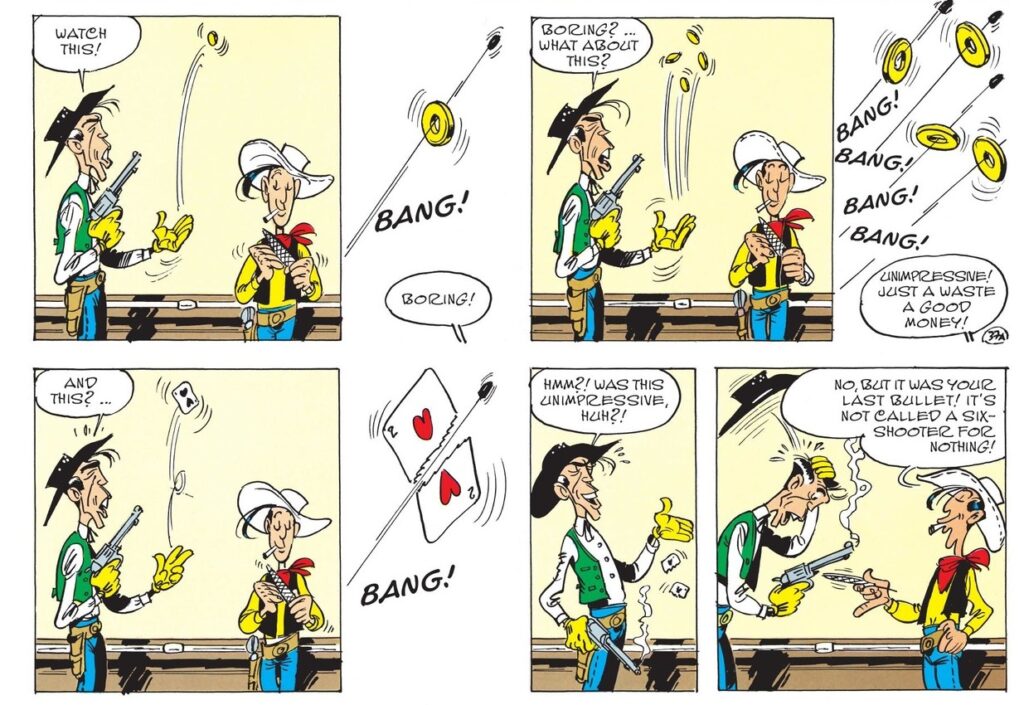

In fact, one of Lucky Luke’s defining features is that he chooses not to kill his opponents (even though he can draw faster than his own shadow, has a pitch-perfect aim, and is pretty good with his fists). This trait may have started out as a concession in order to make the books more kid-friendly, but it generates my favorite kind of stories, where the hero has to constantly *outsmart* the villains.

Steaming Up the Mississippi

The scene above is a running joke throughout the series. Instead of killing each other, Lucky Luke and his opponents constantly deployed ludicrous, non-lethal ways of showcasing their awesome shooting skills.

To be fair, it’s yet another classic setup that has been used in all sorts of westerns and proto-westerns across the decades – and I’m always glad to see new variations on this old motif…

Starlord #12

It’s not just that Lucky Luke doesn’t kill, it’s that his missions typically revolve around instilling morality and protecting – or even helping implement – ‘civilized’ institutions… but this is done in a funny rather than preachy way. René Goscinny isn’t trying to teach you a lesson as much as he’s playing with familiar archetypes, including Luke as the justice-seeking ‘white hat’ cowboy.

Take The Rivals of Painful Gulch. In that album, Lucky Luke arrives at a town where two families – the large-nosed O’Timmins and the big-eared O’Haras – hate each other to death and he agrees to help because their constant fights are ruining the town’s ability to progress (each clan keeps sabotaging every new infrastructure to prevent their rival from benefitting from it). Although the families are obviously Irish caricatures, the tale can be seen as an entertaining parable about racism and prejudice in general. But it also feels like a gloriously wacky counterpoint to Sergio Leone’s Fistful of Dollars (which came out two years after this album) – rather than destroying the town’s clans by pitting them against each other, Lucky Luke has to psychologically manipulate them into getting along!

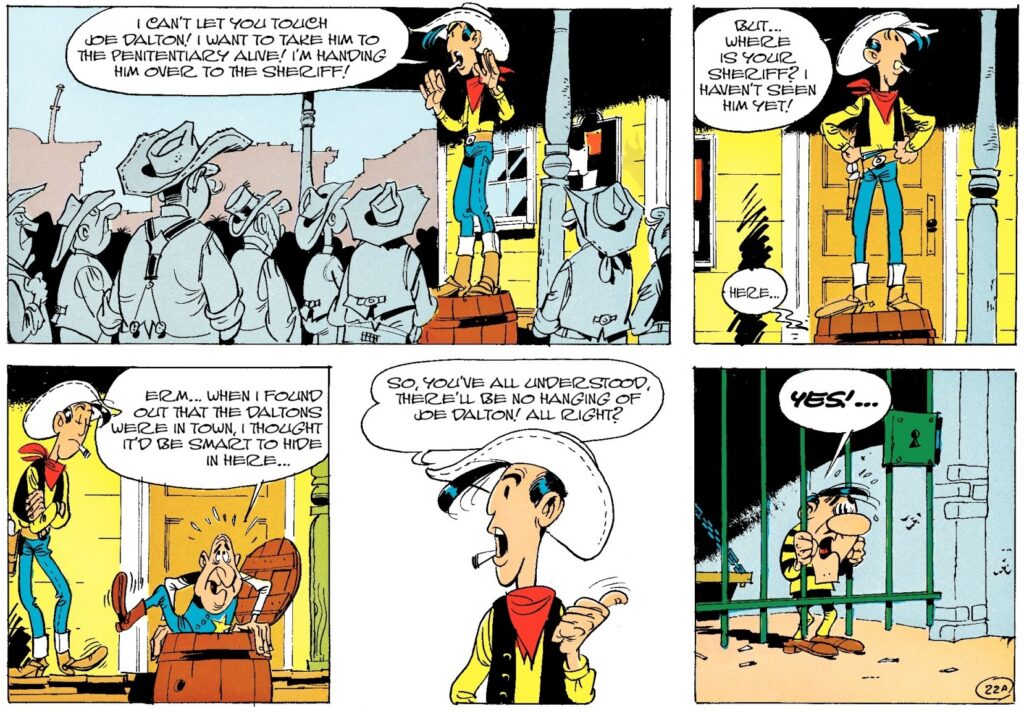

And then, of course, there is the scene from On the Dalton’s Trail where Luke actually saves Joe Dalton from getting lynched…

On the Dalton’s Trail

The key point of the scene is not to romanticize Lucky Luke’s idealism. This is just who he is: standing up for law and order is consistent with his overall characterization. What makes it hilarious is the contrast with the cowardly sheriff, not to mention Joe Dalton’s humiliation (we know how pissed off Jow must be, owing his life to Luke).

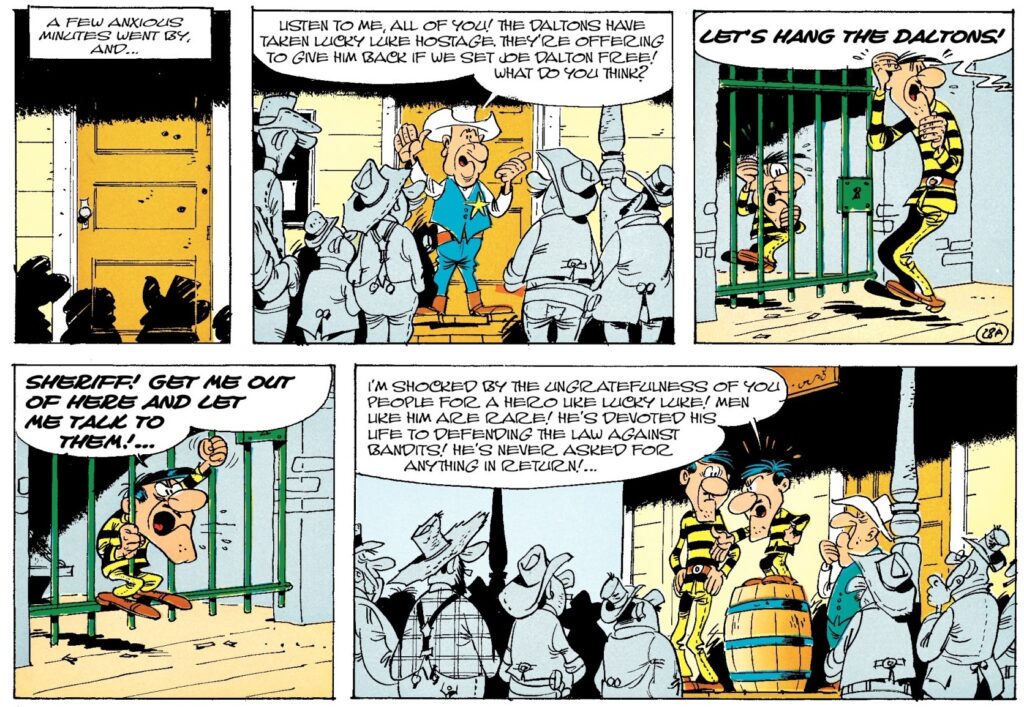

Plus, the scene sets up another one, later on, which pushes Joe Dalton’s position to an even more comical extreme:

On the Dalton’s Trail

Next week, I’ll dive a bit deeper into the politics of Goscinny’s run.