The Dark Knight isn’t the only detective in Batman comics. In fact, having finally read last year’s six-part mini-series Gotham City: Year One, my mind has been on the astounding significance gained by one of the oldest detectives around: Slam Bradley.

Commissioned by Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson and developed by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster (the duo that created Superman), this character made his debut back in 1937, in the very first issue of Detective Comics – in a dreadfully racist ‘yellow peril’ yarn – and kept a regular presence in that anthology for the first 152 issues, until 1949.

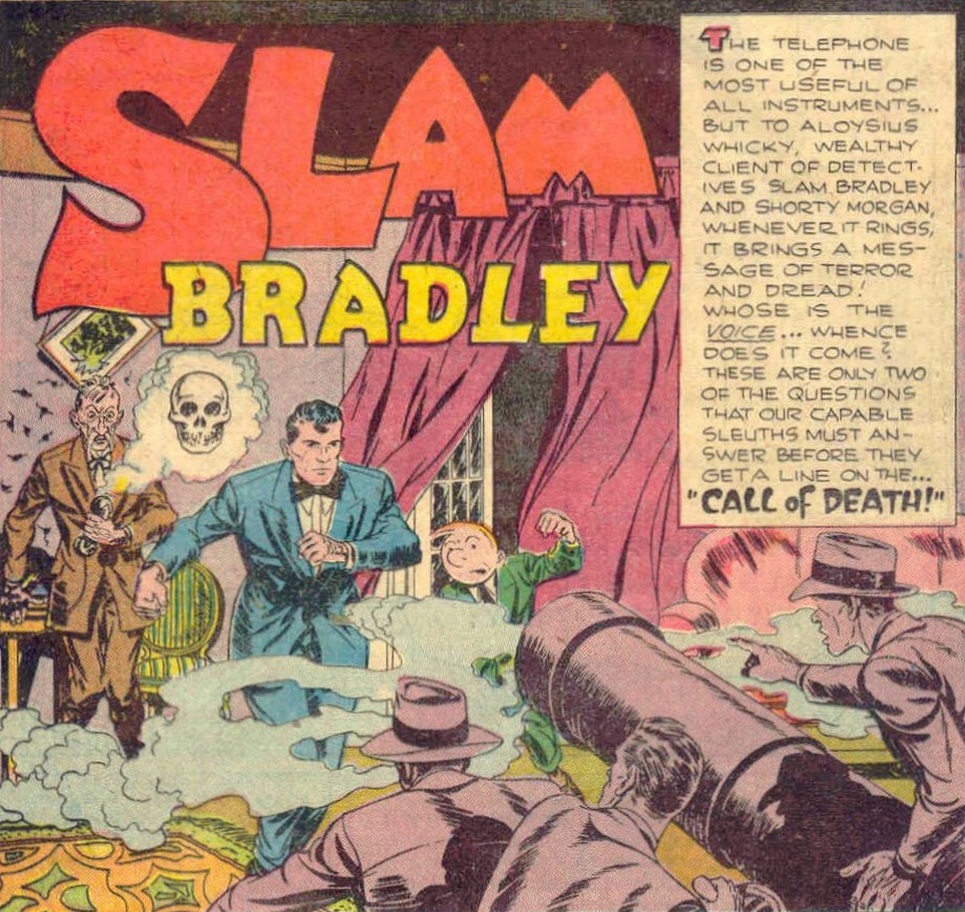

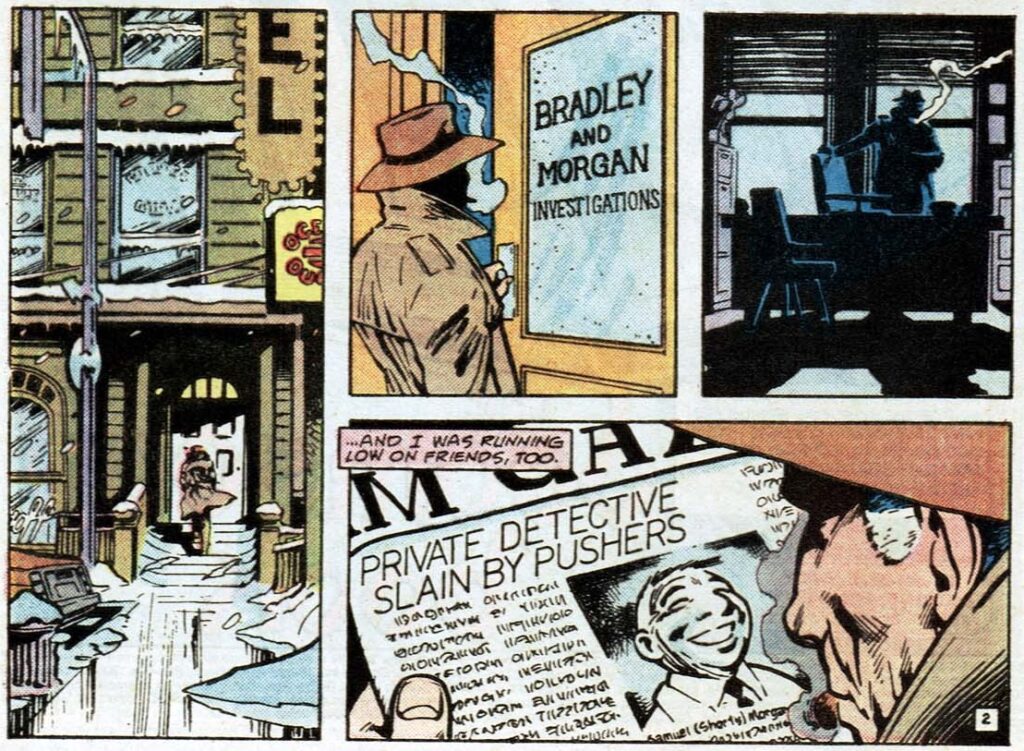

Detective Comics #2

Originally based in Cleveland and, later, Manhattan, Slam Bradley embodied his era’s dominant conception of manliness – he was strong, sharp, and attractive to the dames (even though this latter aspect was eventually downplayed).

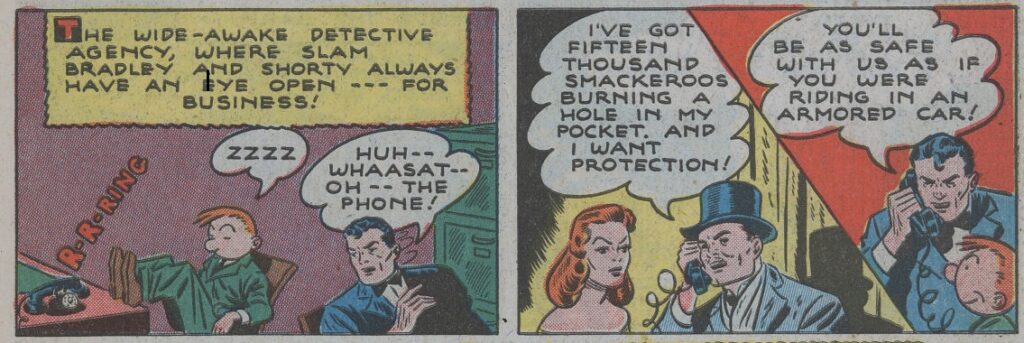

Nevertheless, his feature was one of the cartooniest in the early years of Detective Comics (albeit not as much as Batman’s, of course). Bradley even got a cute goofy – and bewilderingly horny – sidekick, Shorty Morgan, who worked with him in his Wide-Awake Detective Agency…

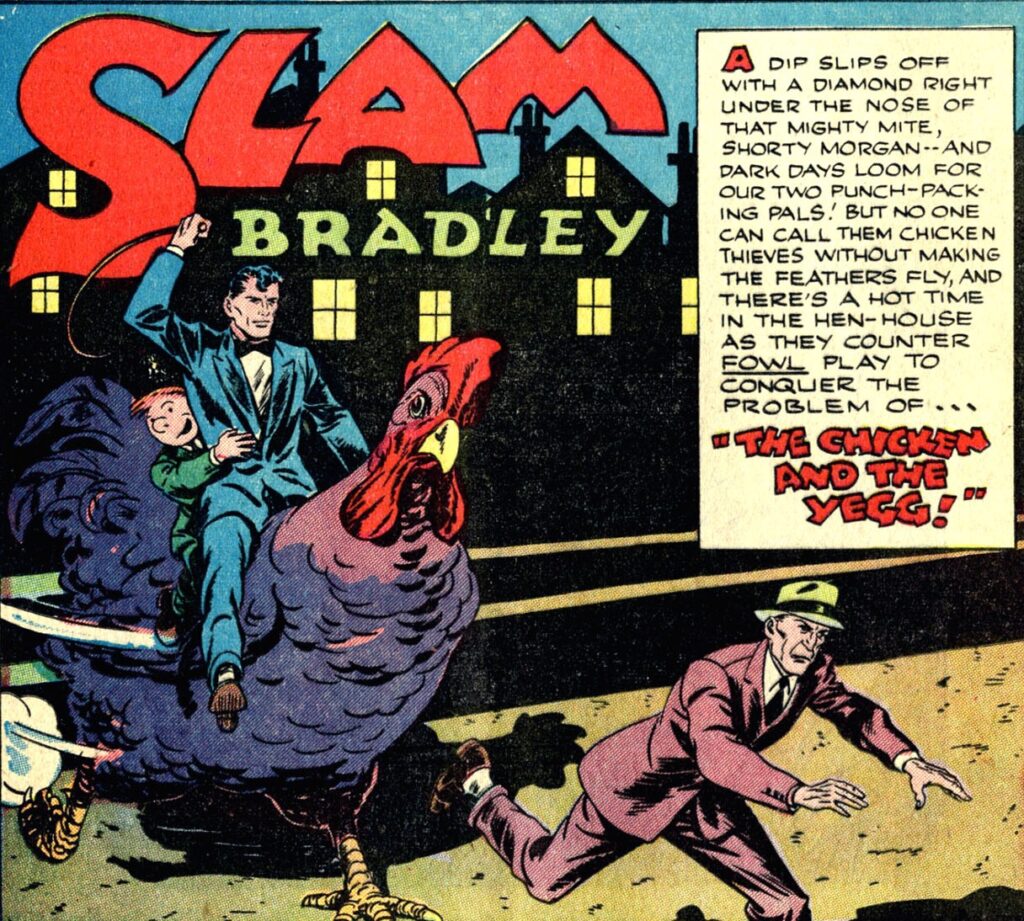

Detective Comics #59

The thing is that, while the character of Slam Bradley himself was played straight as a tough-as-nails sleuth, the tone of his escapades was quite light-hearted. Tales like ‘The Hollywood Murders,’ ‘The Mystery of the Unfortunate Teddy Bear,’ ‘The Case of the Deceased Ham,’ or ‘X Marked the Spot at the Tee!’ fused proper mystery plots with proper comedy, thus belonging to a long lineage of similar hybrids ranging from old movies like The Murderer Lives at Number 21 or The Thin Man (and its absurdly titled sequels) all the way to hilarious novels like Eduardo Mendoza’s The Mystery of the Enchanted Crypt, not to mention Rian Johnson’s recent throwbacks in Glass Onion and the very neat show Poker Face. In comics, the absolute masters of this quirky subgenre are John Allison and Max Sarin (who struck gold once again with last year’s The Great British Bump-Off).

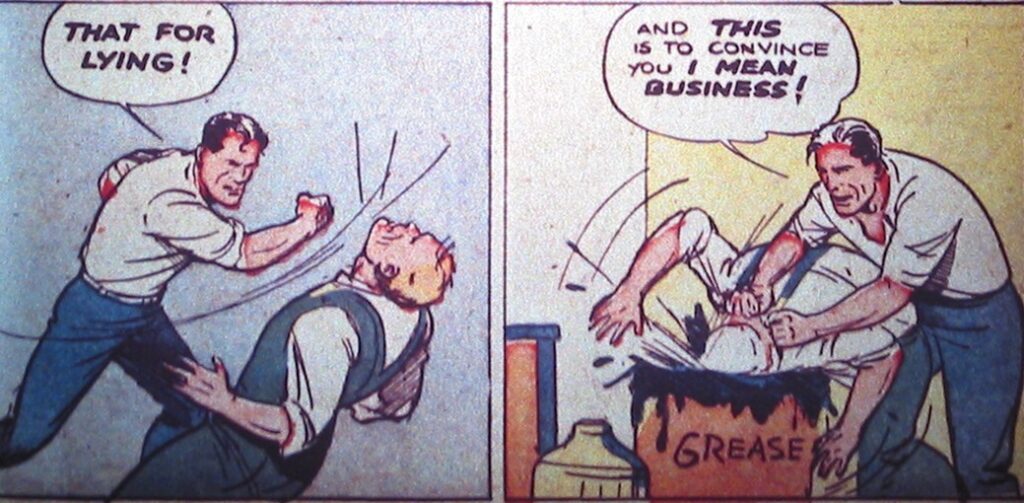

Detective Comics #92

Not that all of Bradley’s cases were necessarily comedic mysteries… A number of them were just straight-up two-fisted action yarns, including plenty of fight scenes and deathtraps that wouldn’t look out of place on a Dynamic Duo story. The twist-filled ‘Slam Bradley in the Stratosphere’ (Detective Comics #18) is pulp adventure at its purest!

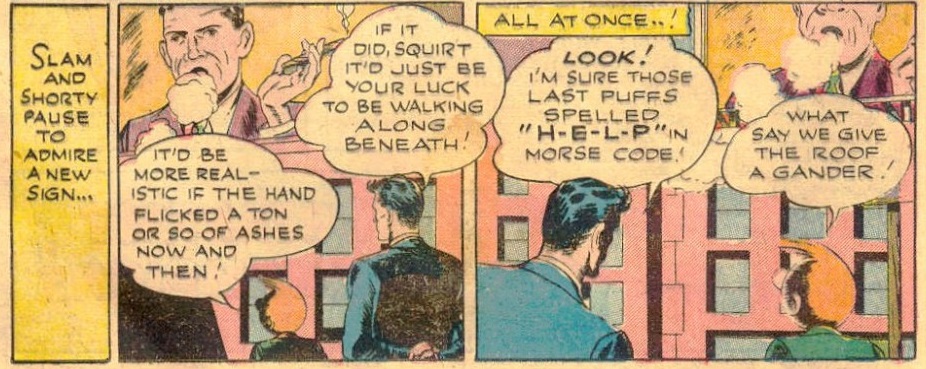

It was thrills rather than cerebral games what got highlighted in the lovely splashes that introduced each story’s premise, especially once Howard Sherman took over the pencils in the 1940s:

Detective Comics #97

And, just like with Golden Age Batman comics, the title splashes were often used to teasingly evoke rather than to accurately depict – they frequently translated the story’s key elements into symbols, creating surrealist compositions (complemented with plentiful puns):

Detective Comics #91

Although he basically disappeared for over three decades, Slam Bradley was such a staple of the initial era of Detective Comics that it’s no wonder creators brought him back for anniversary issues and special occasions.

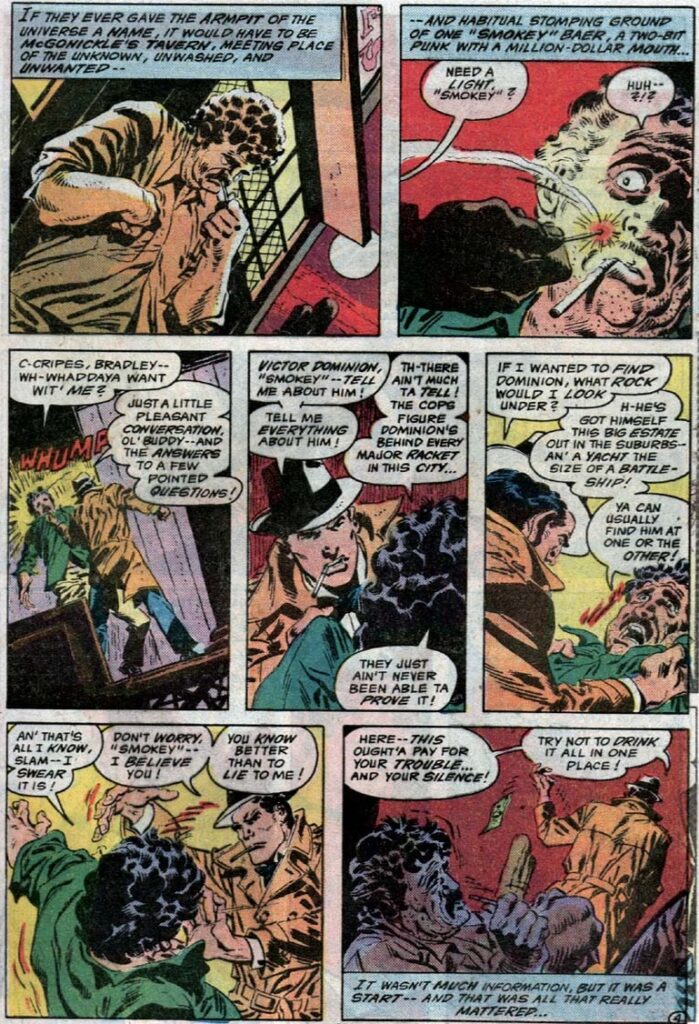

In the 1980s, when American comics were becoming increasingly self-referential and prone to explore their own history (because a new generation of lifelong fans had taken over the industry, because the direct market had developed more of a niche specialized audience with easier access to back issues, or just because postmodernism was generally expanding in the cultural zeitgeist…), Bradley repapered twice, both times in commemorative tales. The first time was for a big team-up of sleuths in Detective Comics #500 (courtesy of Len Wein and Jim Aparo), where he got some of that story’s best lines…

Detective Comics #500

The other time was for Detective Comics’ fiftieth anniversary, in 1987, which featured the awesome tale ‘The Doomsday Book.’ Scripted by Mike W. Barr – one of comics’ greatest mystery writers – that tale paid tribute to various traditions of detective fiction, with Slam Bradley’s demeanour and dialogue patterns evoking the writings of Dashiel Hammett (‘When a man’s client is kidnapped, he’s supposed to do something about it.’)

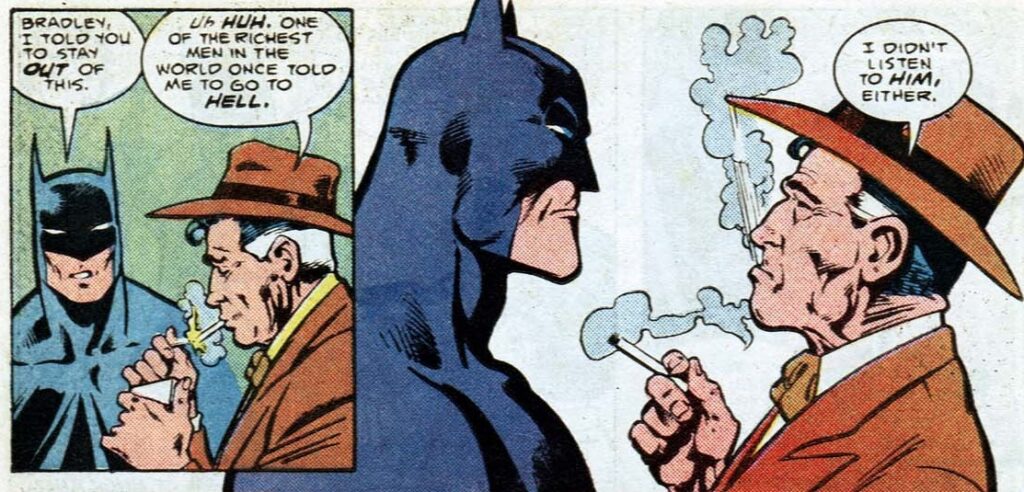

Seeing the hard-hitting Bradley interact with outlandish characters far out of his element – like Batman, Robin, and the Elongated Man – was one of the many, many cool things in that classic issue:

Detective Comics #572

What’s more, Slam Bradley even got a small character arc in ‘The Doomsday Book.’ Slam started the story as a burned out detective who felt old and, after meeting a still fresh Sherlock Holmes, he ended up with a renewed conviction that he still had much to look forward to. This, I assume, was Mike Barr’s metafictional comment about Detective Comics’ own longevity.

Bradley no doubt represented the series’ evolution. He had apparently moved to Gotham City a while back (signalling the shift in Detective Comics’ primary location) and his reality had become substantially grimmer, in contrast to the lighter misadventures he used to have alongside his old partner:

Detective Comics #572

(Shorty Morgan wasn’t just gone, he was ‘slain by pushers’ – welcome to the eighties!)

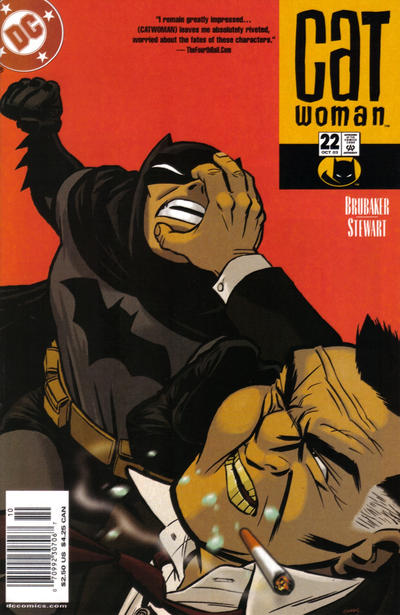

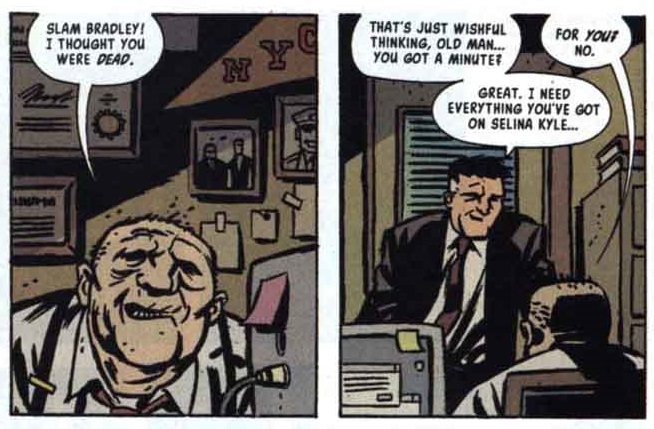

It would take until 2001 for Slam Bradley to return, but this time he came for a longer stay. His character type fit in like a glove within the works of Ed Brubaker and Darwyn Cooke, who were heavily inspired by vintage crime fiction and who fully injected their influences into Batman comics…

Detective Comics #760

Brubaker and Cooke revived Slam Bradley in Detective Comics’ backup feature ‘Trail of the Catwoman,’ where Slam was hired by Gotham’s mayor to find Selina Kyle (who was presumed dead at the time). It was essentially a housecleaning job, streamlining Selina’s post-Crisis continuity, but these two outstanding creators still managed to pull it off as a satisfying hardboiled tale, precisely by telling it from the POV of an engaging outside investigator (i.e. Bradley).

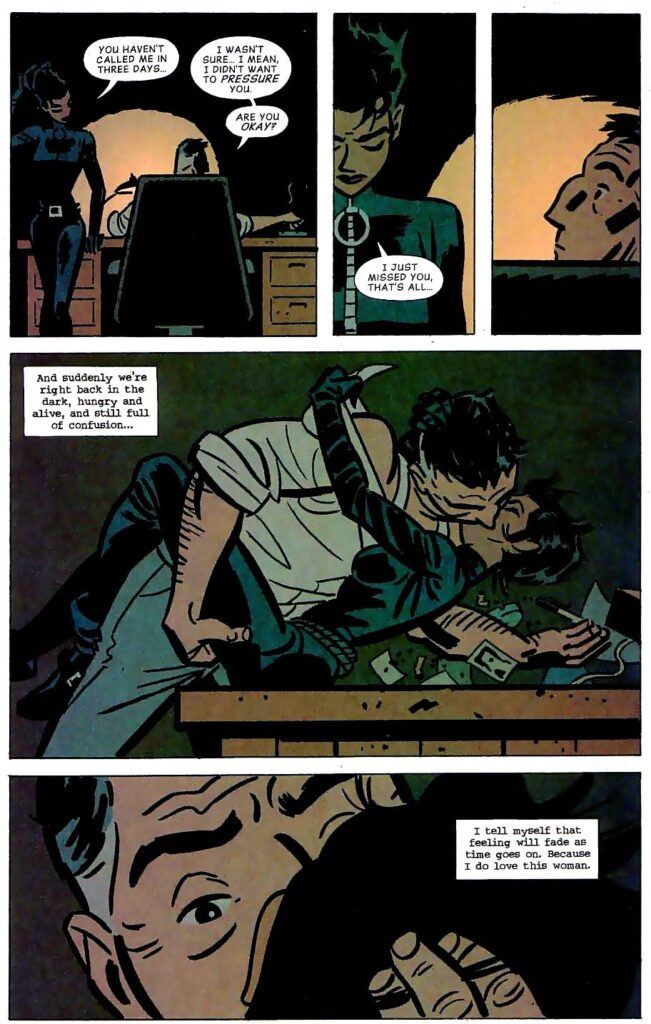

‘Trail’ would prove to be the start of a whole new era in which Slam Bradley became a regular supporting character in Catwoman’s corner of Batman comics. Crucially, the tale established quite a nice rapport between Slam and Selina:

Detective Comics #762

Like Selina, the two creators had clearly found a guy they dug. ‘Trail of the Catwoman’ took place between the pages of Darwyn Cooke’s knockout graphic novel Selina’s Big Score, where Slam Bradley also played a key role. A few years later, Cooke used him to provide the framing story in Solo #10.

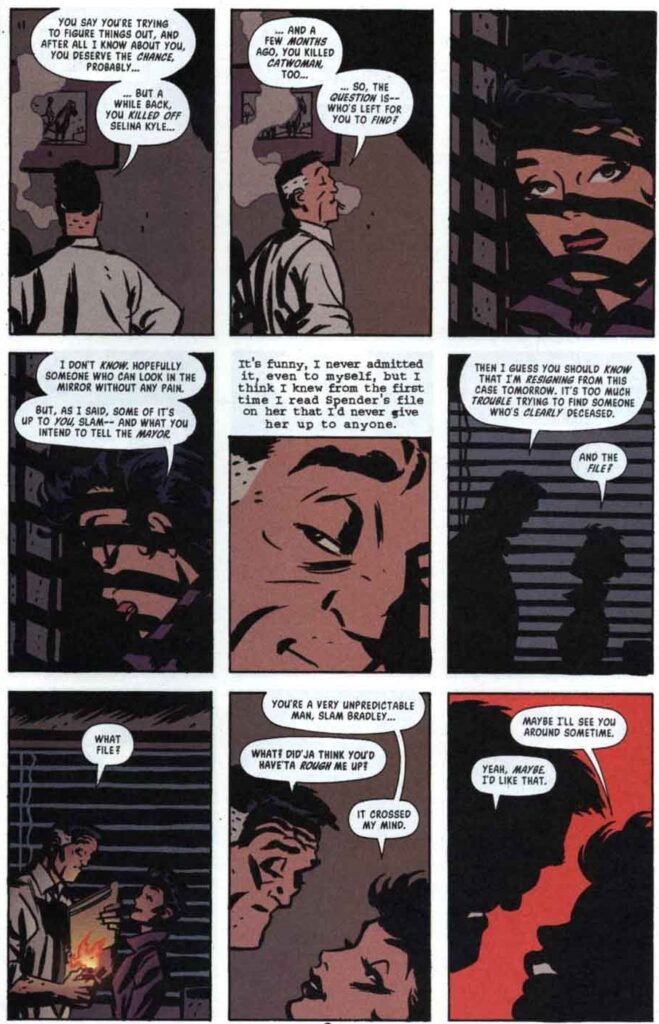

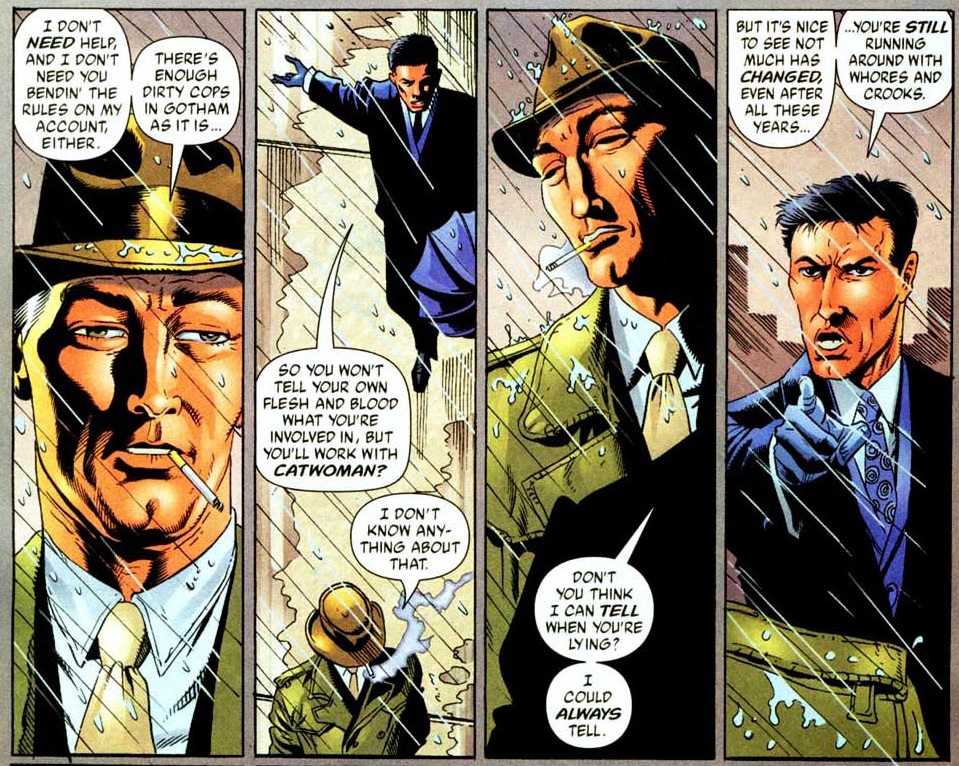

Likewise, Ed Brubaker made Slam Bradley a regular player in his acclaimed run on Catwoman. As I’ve mentioned before, Brubaker enjoys revisiting – and reimagining – the genre stuff he consumed when he was younger, so keeping Bradley around allowed him to juxtapose the ‘voice’ of older crime fiction with 21st-century modernity:

Catwoman Secret Files and Origins #1

More than a mere pastiche or empty exercise in self-reflexivity, musings like the one above helped flesh out Slam Bradley to unprecedented degrees. He gained a more complex personality than the brawling detective of the 1930s-40s. For one thing, he grew in love with Selina Kyle and became jealous of both Bruce Wayne and Batman (with whom he got into a fistfight over her… Bad call!).

Slam and Selina even developed a beautifully melancholic and precarious relationship, laden with realistic and recognizable insecurities… This tough he-man thus revealed a whole new layer of inner vulnerability:

Catwoman (v2) #17

Visually, Slam Bradley’s rugged, square-jawed PI always brought to my mind Dick Tracy, especially in the context of Catwoman’s stylized art in this era…

But then Paul Gulacy came in as artist and drastically changed the series’ aesthetics into more photorealistic designs – it was as if everyone had suddenly been recast mid-season. Typically drawing on influences from cinema, Gulacy turned Slam Bradley into Robert Mitchum (who had not only played a private eye in the amazing film noir Out of the Past, but had also gone on to play an ageing Phillip Marlowe in the 1970s’ adaptations of Farewell, My Lovely and The Big Sleep).

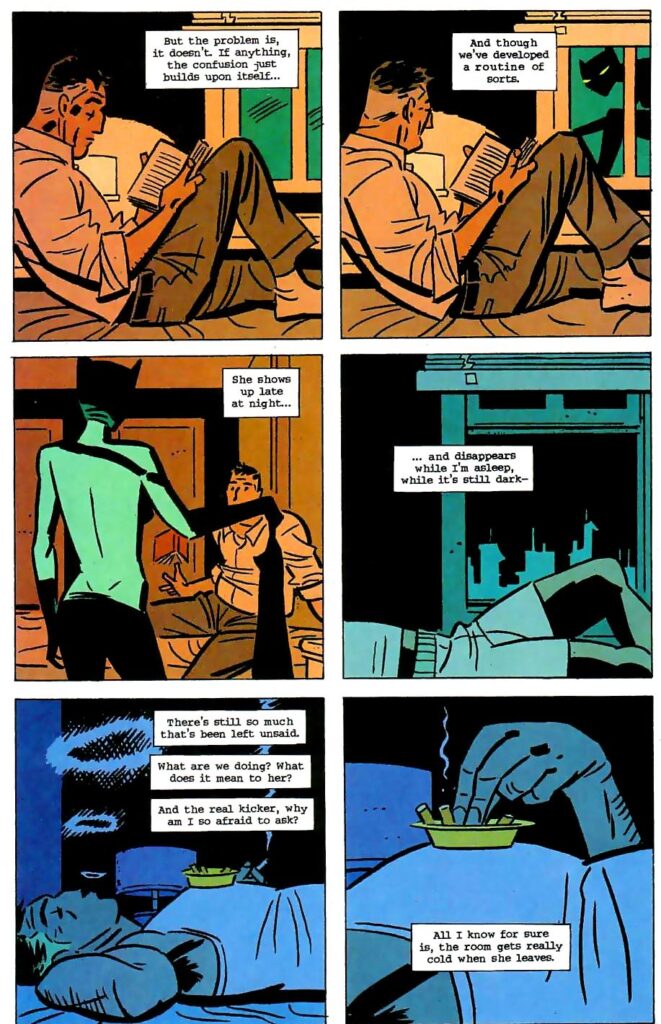

Further shaking things up, Catwoman introduced Slam’s son – a young cop named Sam with a chip on his shoulder:

Catwoman (v3) #29

Regardless of changing looks, in the early 2000s Slam Bradley had become a recognizable character once again, at least among a certain kind of mid-level fan. What’s more, he was now a bona fide Gothamite. He popped up in Gotham Central #26-27 and was seriously tortured by Black Mask in Catwoman #51. In 2014, Adam Hughes included Slam in a short story he did for Batman Black & White (v2) #6 and, five years later, the character lent his gravitas to yet another cool commemorative tale, Scott Snyder’s and Greg Capullo’s ‘Batman’s Longest Case,’ in Detective Comics #1000.

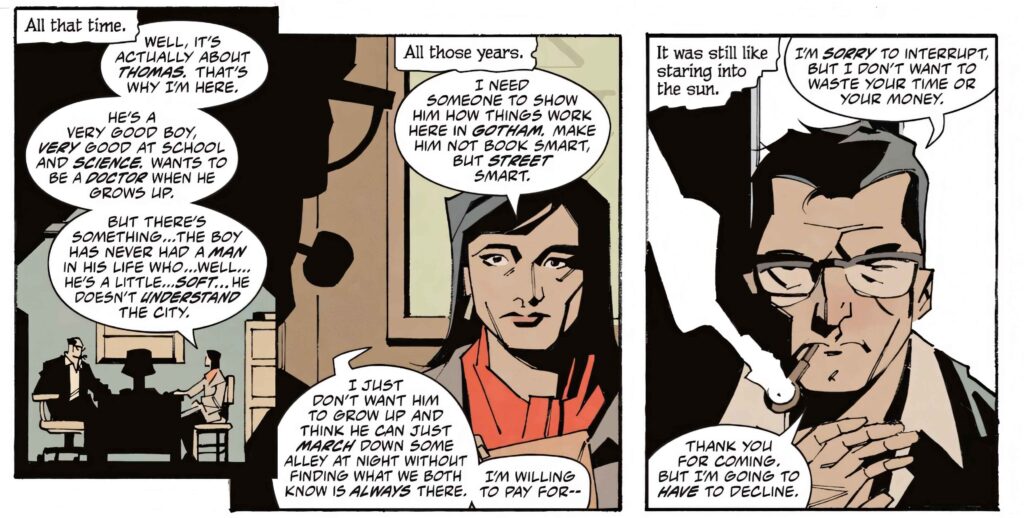

Given all this background, it makes sense that Tom King chose Slam Bradley as the protagonist of Gotham City: Year One, a noirish mystery yarn revealing/retconning the origin of Gotham’s fall from grace into urban chaos two generations ago (in the early 1960s). Bradley feels right at home in this type of story and the fact that he inaugurated Batman’s ‘home’ (he was right there at the beginning of Detective Comics, whereas the Caped Crusader only made his debut in issue #27) adds the sort of subtext King is usually fond of.

Slam Bradley’s advanced age – both as a character (he’s 94 in present day continuity) and as an intellectual property (created 87 years ago) – lends resonance to the tale’s theme of reconsidering the past, exposing how one’s clean, nostalgic era of safety and prosperity can be someone else’s dirty, traumatic nightmare of police brutality and systemic inequality. The notion of a black community starkly marginalised from the wealthier side of town plays a central role in Gotham City: Year One, which makes it even more pertinent to use Slam as a bridge between the two worlds, given the character’s historical links to racism in comics and in his wider branch of macho adventure narratives. The book is full of brutal situations, even if the swear words are replaced by symbols (because language is apparently the greatest taboo). In particular, there is an emphasis on the issue of racist violence and torture (the reason Bradley quit the force), which may be a way for Tom King to work through his own seven-year stint at the CIA’s counterterrorism operations in the early 2000s.

Before delving further into the books’ themes (including a couple of *major* spoilers), let us consider the dazzling artwork:

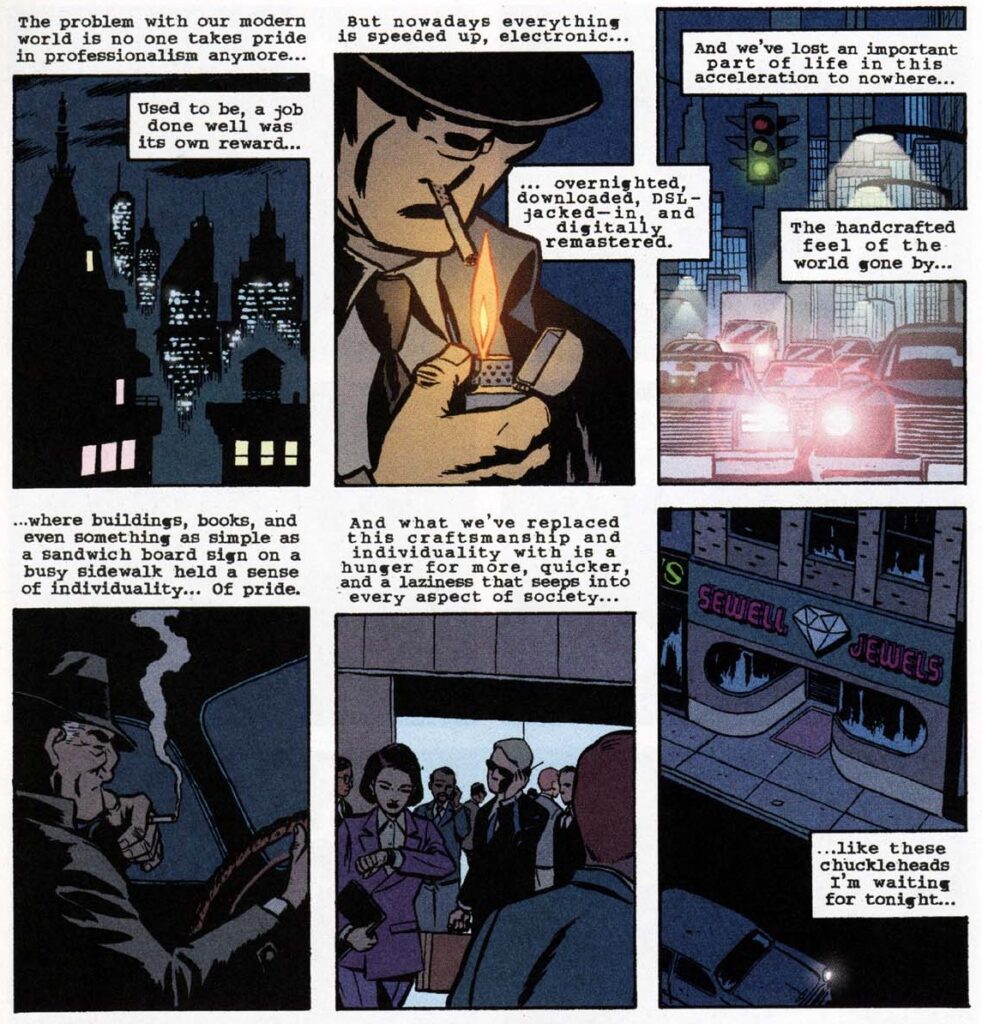

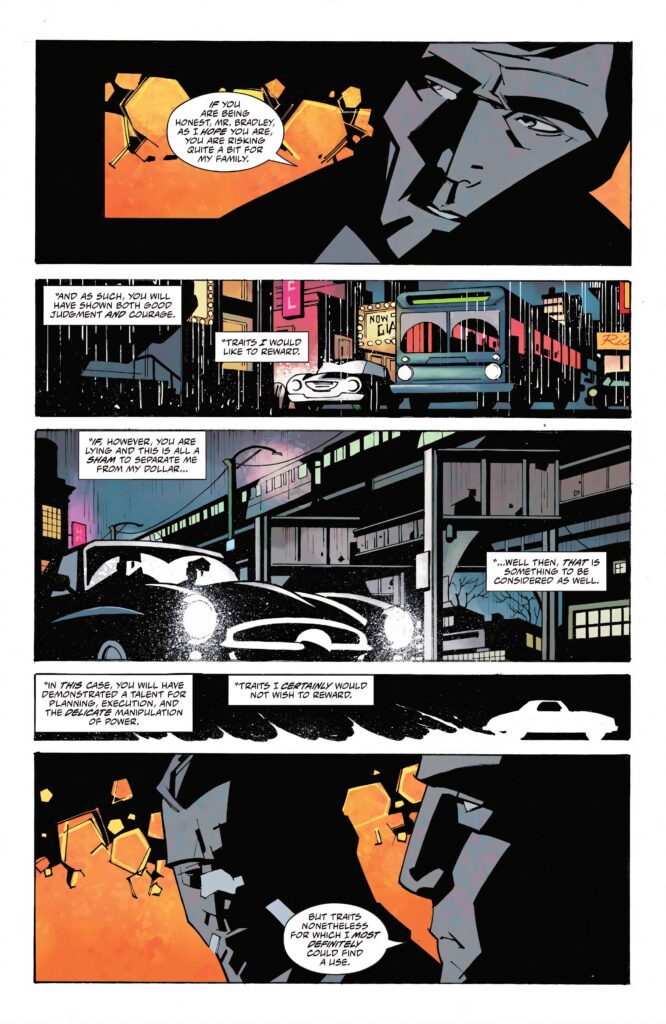

Gotham City: Year One #2

Penciller Phil Hester, inked by Eric Gapstur, pushes his typically blocky, angular figure work to Frank Miller-esque levels, which colorist Jordie Bellaire superbly builds on to create a series of mesmerizing visuals (like the orange squares in the panels above, translating the city lights through the window of a moving car). The black & white in the penultimate panel evokes classic film noir and the PI with the broken nose evokes Chinatown, perhaps filtered through Miller’s Sin City. Although you can’t see it in this scan, letterer Clayton Cowles joins the game by presenting Slam Bradley’s narration as torn pieces of typewritten paper…

Tom King’s script takes intertextuality even further. Besides doing the usual trick of naming Gotham’s streets and locations after real-world Batman creators (‘Went to the old Austin junk between Aparo and Grant.’), thus inscribing the comics’ past into the city’s toponomy, King also adds some significant twists to the franchise’s mythology, including: 1) Slam Bradley’s mother is black; 2) he is probably Bruce Wayne’s biological grandfather.

The first of these twists wouldn’t be all that remarkable, except for the fact that race and genes occupy such a vital place in US culture. I suppose it inserts Bradley into yet another subset of crime fiction, namely all those great gritty novels about the African-American experience, like Chester Himes’ Harlem Detectives series or J.F. Burke’s Sam Kelly trilogy, not to mention Gil Scott-Heron’s The Vulture. What makes this revelation more meaningful is the articulation to the second twist, since it means that Bruce Wayne has black ancestry, which can be seen as ironic given that he is often presented as a bastion of white privilege.

The second piece of revisionism works better on a meta level than on a diegetic one. Thematically, it recasts Batman as a direct descendent of a hardboiled private eye (again, one who kicked off Detective Comics). And while Gotham City: Year One tarnishes the legacy of the Wayne surname – and even of the Batcave, as it was previously used to collect sexual trophies – the series arguably makes Bruce himself a more romantic hero: rather than just a product of the elites, his history is now linked to the downtrodden masses.

In turn, the detective skills of both Slam Bradley and the Dark Knight don’t come off well, since neither of them appears to even consider the possibility that they’re related – but hey, I guess we all have our blind spots. Their failure to explicitly acknowledge what’s at stake may be just an editorial strategy to preserve ambiguity (so that DC doesn’t have to commit to this story’s implications in the future), even though the likely link between the two characters is pretty much telegraphed to the readers (Cowles even highlights the word ‘grandfather’ through bold and italics, in the final page).

Tom King is an intelligent writer, but it seems he just can’t help himself. He manages to add a connection to the Joker’s origin and, just before the series is over, he closes the larger narrative even more tightly, making Slam responsible not only for Bruce’s birth, but also for the very creation of Batman… at least according to the oddly prescient (and sexist) perspective of Bruce’s grandma:

Gotham City: Year One #6