Since I did a couple of posts about The Adventures of Tintin a while back, I guess it was a matter of time before I got around to writing about Spirou & Fantasio, the other major classic series of Belgian bandes dessinées about madcap globetrotting adventure.

In particular, I want to focus on the first decade or so after World War II, when the series was both written and drawn by one of the greatest geniuses in the history of cartooning, André Franquin.

Despite its long-lasting popularity in continental Europe, most albums of Spirou & Fantasio have yet to be translated to English (although Cinebook and Europe Comics, slowly but surely, have finally been doing a praiseworthy job at fixing this). Indeed, the series never reached the same level of critical acclaim – and scholarly discussion – of The Adventures of Tinitin… not even close!

One reason for this may be, precisely, the inescapable comparison with Tintin. After all, although Spirou has different hair, a different attire (he is often dressed like a bellhop, strangely), and a different adorable pet (Spip the squirrel, instead of Snowy the dog), he has pretty much the same personality as Tintin: a young, curious, friendly, (initially) asexual hero with smarts and a kind heart. Spirou’s hotheaded-but-well-meaning sidekick, Fantasio, is a version of Captain Haddock, albeit less politically incorrect and not a sailor… in fact, he’s a reporter, like Tintin. The comparison can go on: they often hang out at a palace with an old inventor who at one point builds a model submarine!

Above all, they get involved in a very similar type of all-ages Boys’ Own thrillers…

The Wrong Head

This parallel became more superficial as the series developed its own identity and mythology – and it didn’t appear to bother readers in the first place (I remember accepting the derivative features as a serviceable springboard for fun rip-roaring yarns when I was a child… Hell, the fact that the whole thing at first seemed Tintin-like was a bonus, as I was looking for more of the same anyway!). Still, when it comes to the medium’s intelligentsia and academia, I’m not sure Spirou & Fantasio ever fully cast aside the negative connotation of being a less sophisticated copycat of a critical darling.

All of it written and drawn (or closely supervised) by Hergé, The Adventures of Tintin feels shaped by an auteur’s artistic vision and evolving personal concerns – i.e. the type of stuff scholars and critics love to scrutinize and evaluate – while Spirou & Fantasio, in turn, comes across like much more of an industrial franchise: the character of Spirou was originally created by cartoonist Rob-Vel, in 1938, for the leading strip of the magazine Le Journal de Spirou; it became property of the publisher Dupuis during WWII; Jijé introduced the co-lead Fantasio (who also went on to be a key character in Franquin’s hilarious strips about Gaston Lagaffe, known in English as Gomer Goof); and the series has been passed around from one creative team to the next throughout the ages, to the point that new albums – and spin-offs – by different writers and artists keep coming out almost every year, with flexible internal continuity (for example, some are set in the present and others in the distant past, although the characters usually have the same age).

I realize I could be describing Batman or loads of other IPs from American comics but for a long time this made Spirou & Fantasio relatively exceptional in the European scene… and probably made it earn less respect and less close attention than the finite opus that is Tintin.

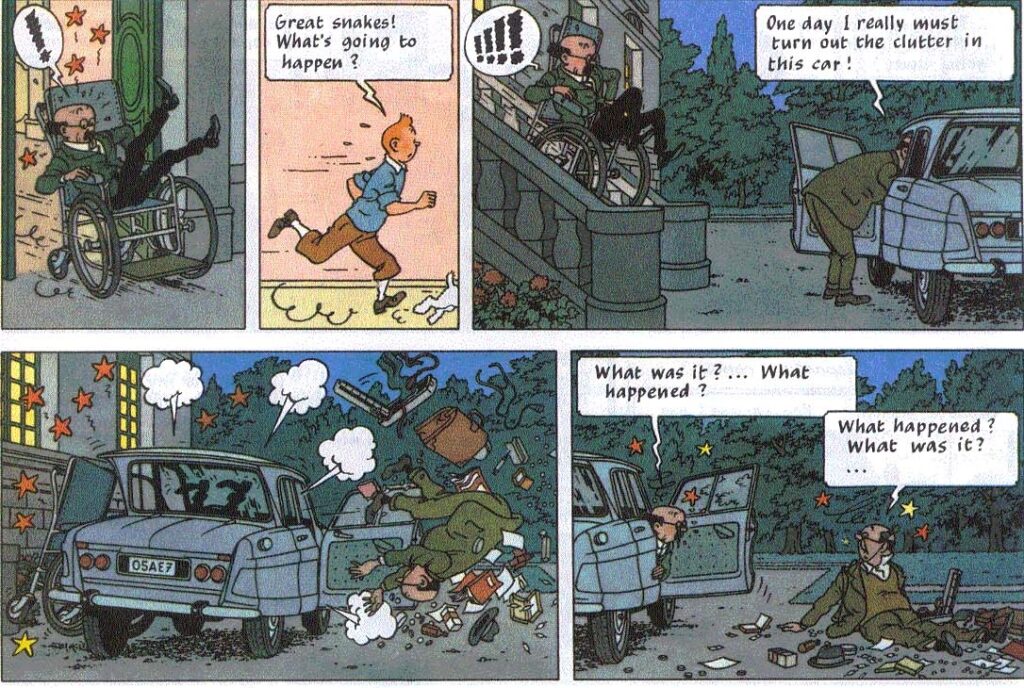

I’m sure it didn’t help that the series was more prominently comedic, as well. Don’t get me wrong, Tintin is certainly humorous…

The Castafiore Emerald

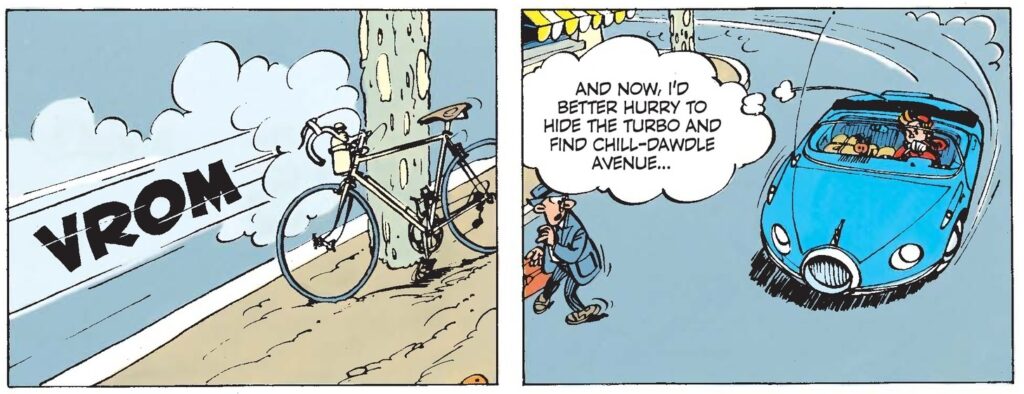

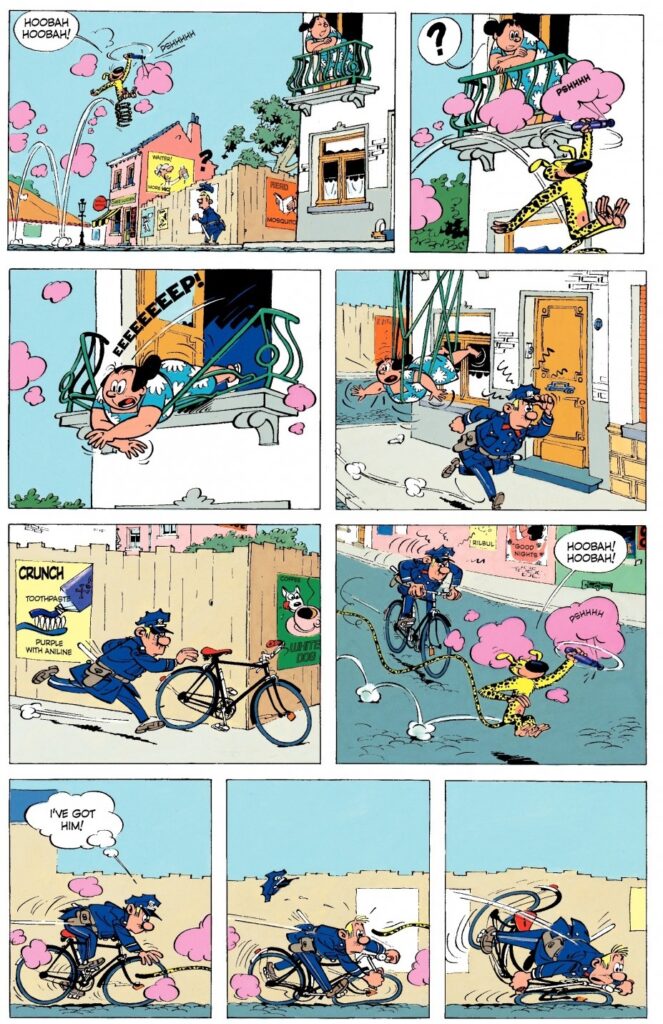

However, the tone of Spirou & Fantasio has always been much more playful (with a couple of exceptions), including outright surreal and metafictional gags. André Franquin no doubt played a major role in popularizing this aspect when he took over the series, in 1946: if Hergé’s ligne claire was sometimes used to render physical comedy in an anchored, quasi-realistic, and comparatively stiffer world (as seen above), Franquin’s Spirou pushed the slapstick further while drawing everyone – and everything – as elastically cartoony, within relative boundaries.

At one point, Franquin even came up with a gas that diegetically made solid metal soft and malleable:

The Dictator and the Mushroom

There is a case to be made that Franquin’s Spirou and Fantasio is not just a more whimsical version of The Adventures of Tintin, but ultimately a kind of good-natured parody of Hergé’s work. Like Tintin in The Broken Year, the two heroes travel to a fictional country constantly embroiled in revolution – in this case, Palombia – in Spirou et les héritiers [‘Spirou and the Heirs’, one of several albums bafflingly untranslated to English, all the more so because it introduces many recurring elements and cast members]. When Spiro and Fantasio get there, however, they find something much more frantic: every important building they look at immediately explodes and the streets are littered with chaotic gunfights and tanks. If Hergé caricatured Latin American politics, Franquin seems to be spoofing that very caricature!

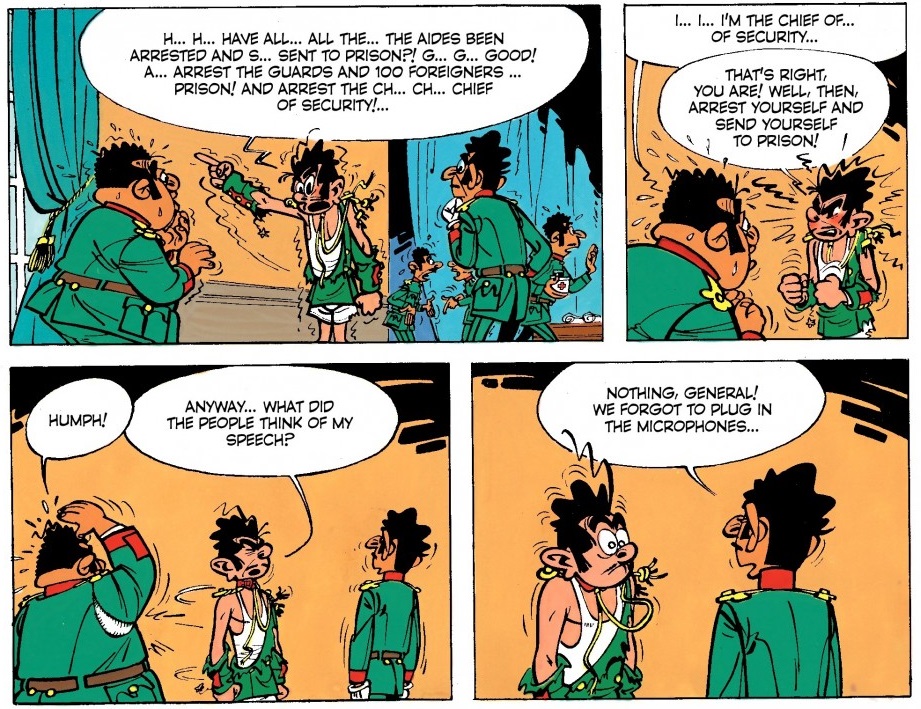

Even when he plays the material straighter, in the sequel, The Dictator and the Mushroom, Franquin seems less interested in satirizing imperialism than Hergé did in The Broken Ear or, later, Tintin and the Picaros. It is a pacifist tale (Spirou and Fantasio try to sabotage Palombia’s military arsenal before its latest leader invades a neighboring country) but the story doesn’t seem informed by specific geopolitics, only by a general impression that this part of the world is full of warmongering regimes (yes, the Cold War only fully blasted into Latin America with the coup in Guatemala of 1954, a year after this album came out, but almost two decades before Hergé had already linked the region’s violence to neo-colonial interests…).

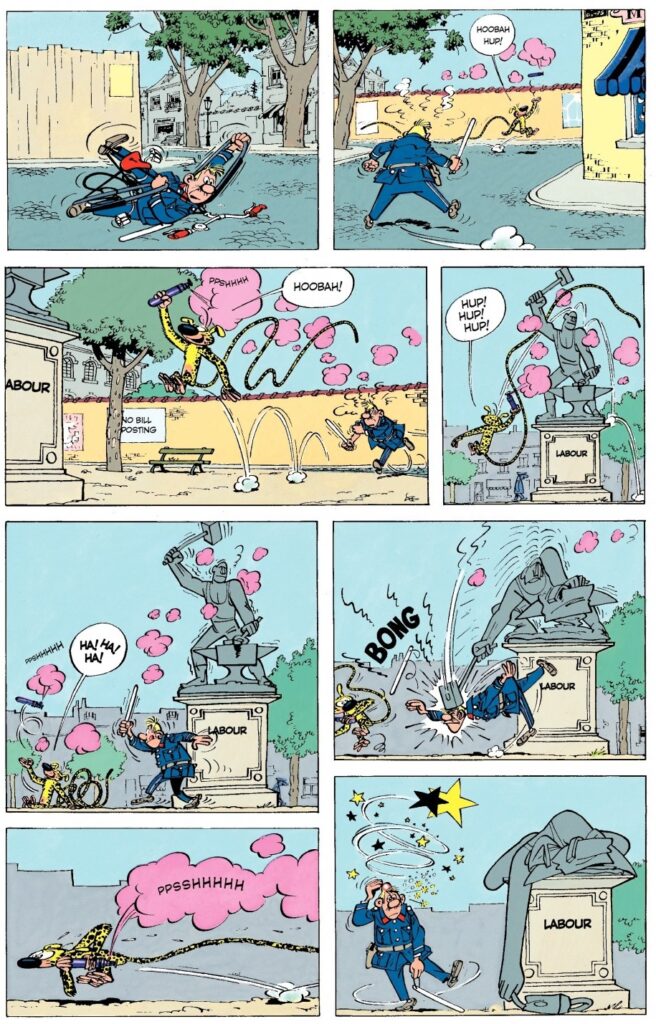

If there is a political angle here, it’s the liberating joy of laughing at buffoonish authoritarianism:

The Dictator and the Mushroom

Seen from this prism, Franquin’s run appears less like a poor imitation of The Adventures of Tintin than like a talented cartoonist taking a familiar blueprint (like Hergé had done with the works of Jules Verne and Alfred Hitchcock) and filtering it through his own idiosyncratic sensibilities. In other words, it can be read as an auteur piece on the same level of Tintin, not least because Franquin’s output was itself incredibly groundbreaking and influential.

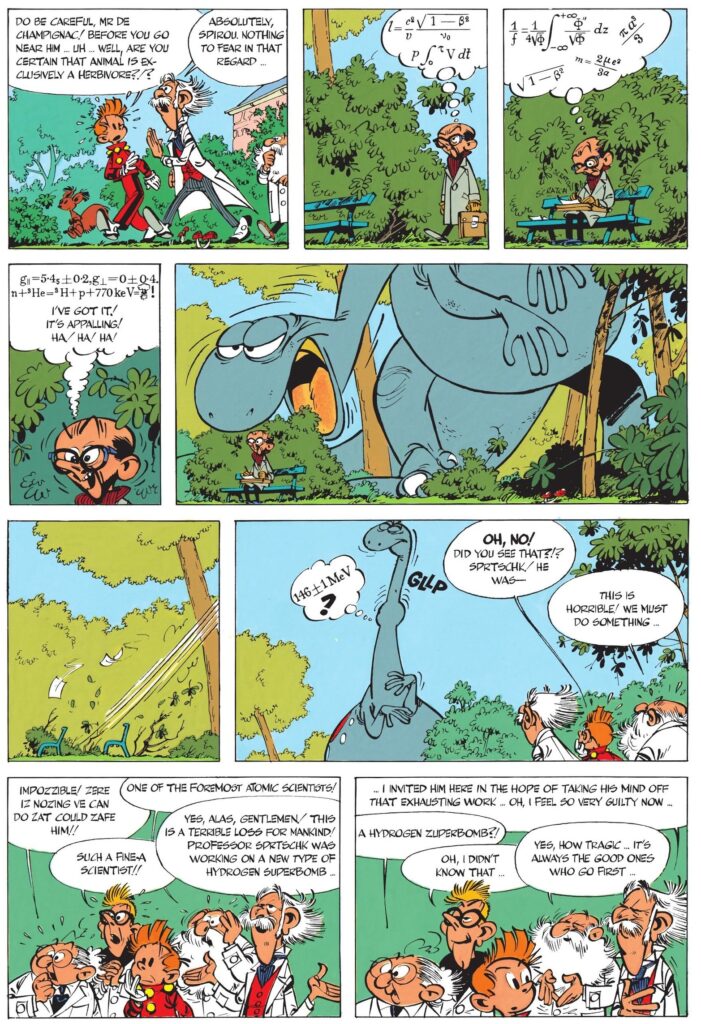

While Franquin’s plotting was thinner and probably improvisational (at least early on), he was quick to introduce a bunch of concepts and visuals that have remained a lasting staple of Spirou & Fantasio (and which have themselves been imitated by other series), from Fantasio’s despicable cousin Zantafio to the competitive reporter Cellophine (Seccoutine in the original), not to mention the exotic animal Marsupilami (a prodigy of design and frequent deus ex machina) or the village of Champignac-en-Cambrousse, with its pompous mayor (so proud of the village’s first – and apparently useless – traffic light) and its eccentric count/grandfatherly master of mad science.

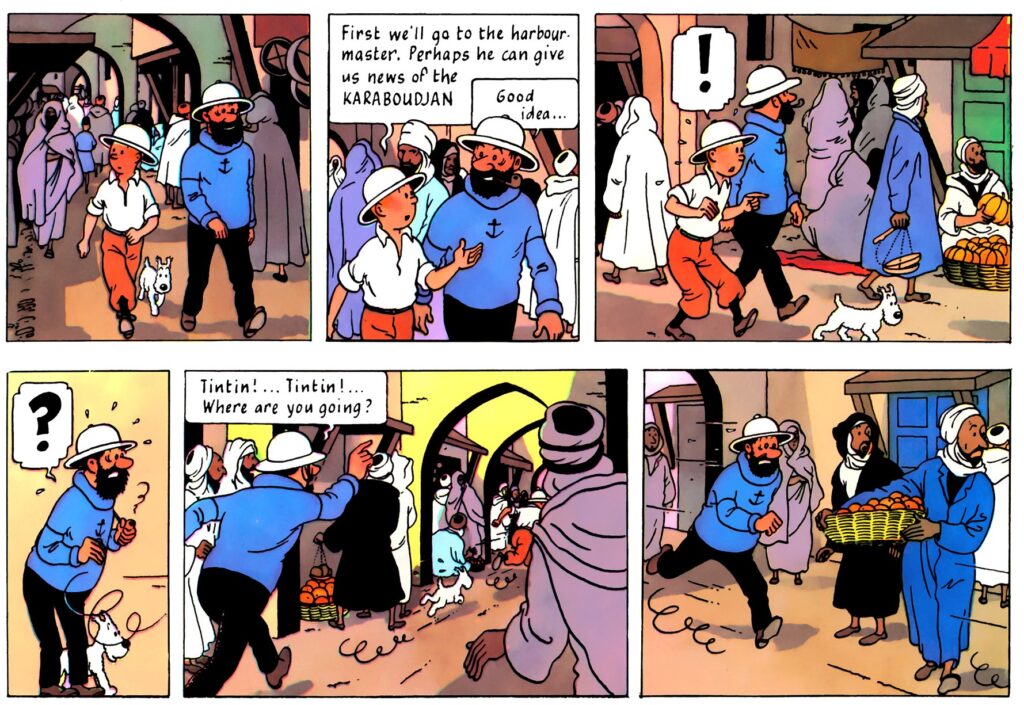

Notably, Franquin’s distinct drawing style displayed a flair for imaginative and amazingly fluid designs, which he often applied to gizmos (including some very cool vehicles!) and to action set pieces. Again, compare Hergé’s and Franquin’s depictions of North African architecture – while the former carefully traced reference photos and came up with credible backgrounds…

The Crab with the Golden Claws

…the latter filled the pages with deliberately skewed lines, less concerned with realism than with projecting the dizzying sensation of a foreign look at the seemingly labyrinthine kasbahs:

The Rhinoceros’ Horn

Is it a colonial gaze? You bet. And wait until you see his take on sub-Saharan tribalism in the same album… or the one in Le gorille a bonne mine [‘Gorilla’s in Good Shape’], for that matter. Like Will Eisner – and, yes, Hergé – Franquin, although a gifted artist and in many ways social conscious, was unfortunately not above the shameful ethnic stereotypes so in vogue at the time.

Then again, 1951’s Il y a un sorcier à Champignac [‘There is a Sorcerer in Champignac’] anticipates the subplot about racism against the Roma from the 1963 Tintin album The Castafiore Emerald. Indeed, like I mentioned about both Tintin and Lucky Luke (by Franquin’s close friend, Morris), racist imagery and humor do not preclude a compassionate undercurrent in these comics. For all of their forays into unbridled mayhem and grotesque caricature, the early stories of Spirou & Fantasio were informed by a remarkable empathy with people as well as animals.

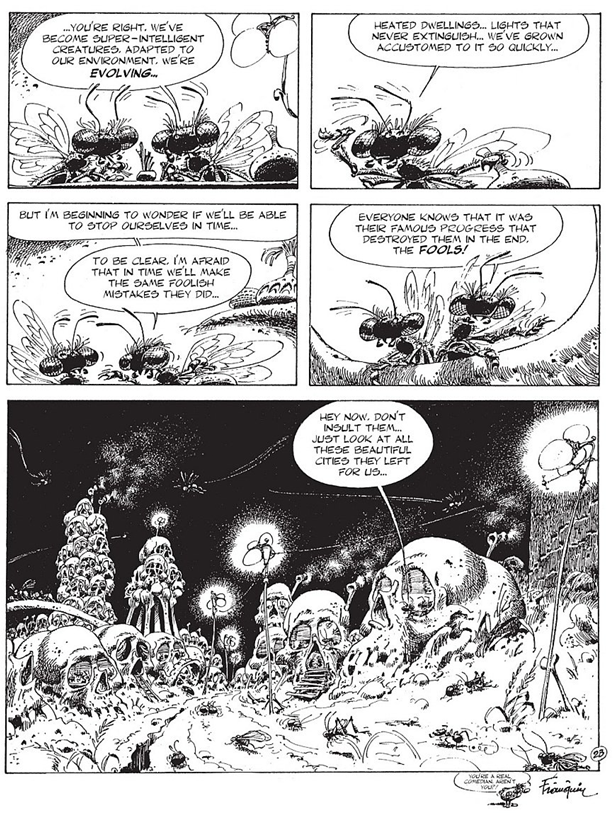

Decades later, Franquin would indulge in glorious misanthropy through the brilliant cartoon series Idées Noires (published in English as Franquin’s Last Laugh and Die Laughing):

Franquin’s Last Laugh

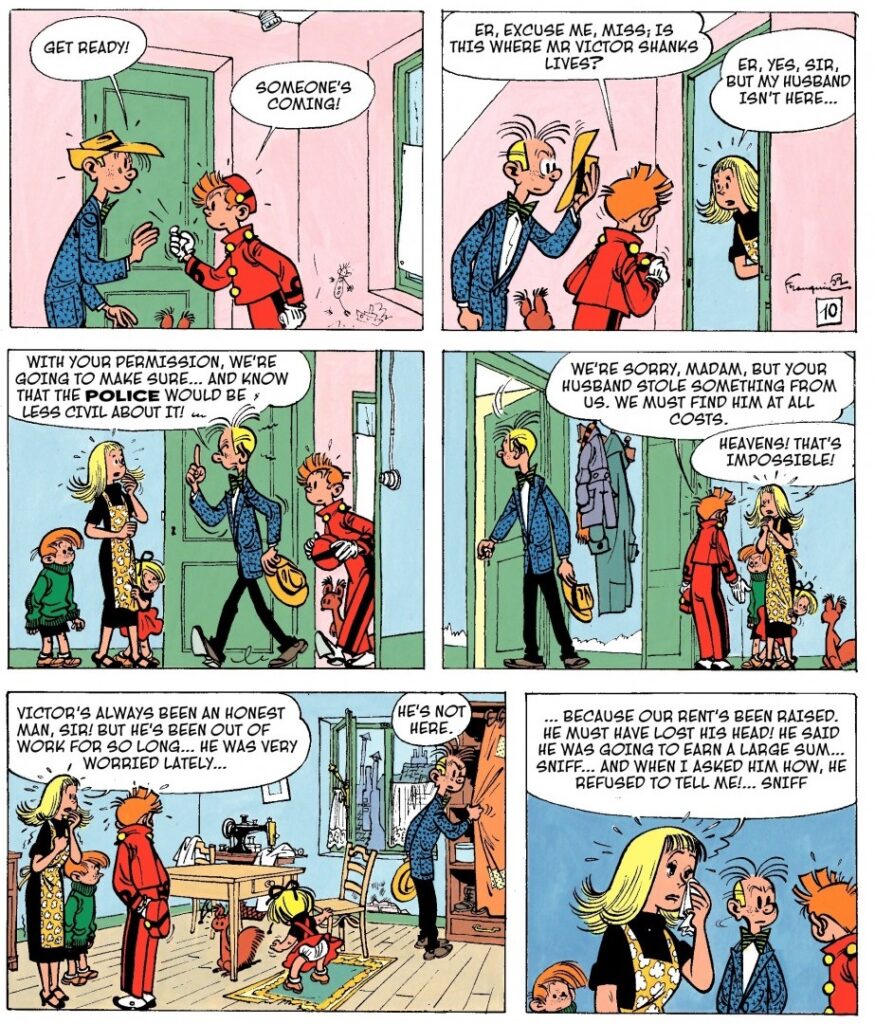

Yet Franquin actually started his career doing upbeat, lighthearted comics where the stakes were frequently somewhat low, suggesting a world of big children where even the villains seemed more mischievous than downright evil…

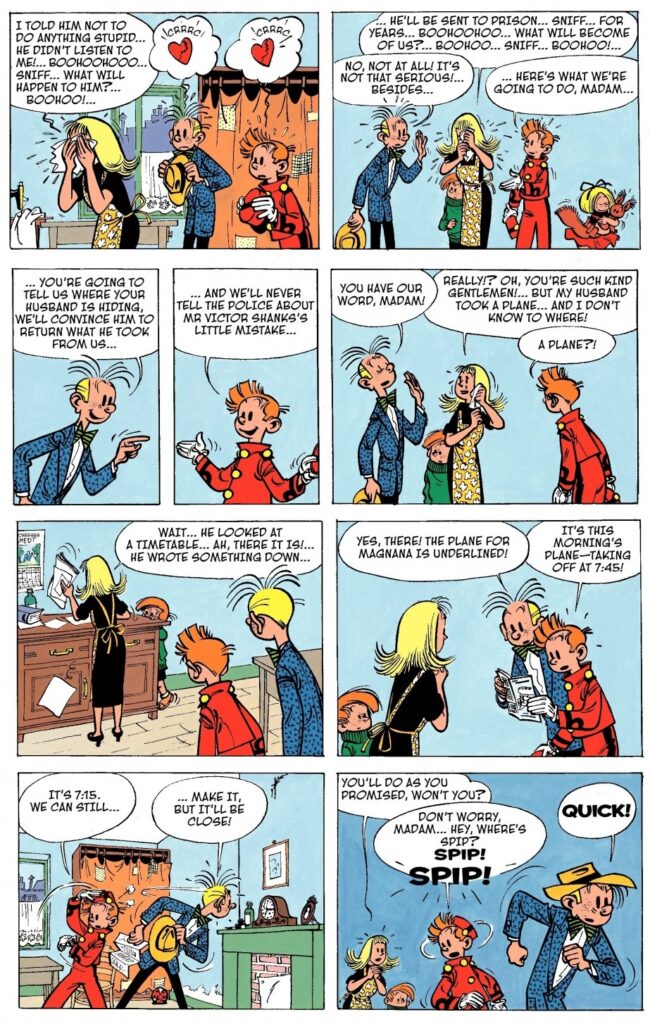

In his Spirou & Fantasio, most criminals were just trying to make a buck in a difficult situation, which was presented as understandable and ultimately forgivable:

The Marsupilami Thieves

I love how, in the pages above, Franquin enriches what could’ve been a schmaltzy exposition scene through the Spip subplot, told wordlessly almost until the end at the lower level of the panels… Indeed, his artwork is chockful of nifty details. Notice, in the final panel, an ad for the very magazine that readers are reading, proof that self-reflexive Easter Eggs have a very long tradition in pop culture (as early as 1928, Fritz Lang’s Spies featured, in the background, a poster advertising his previous film, Metropolis). The sheer aesthetic pleasure and the captivating flow of movement make these comics worth tracking down even if you can’t find them in your native language.

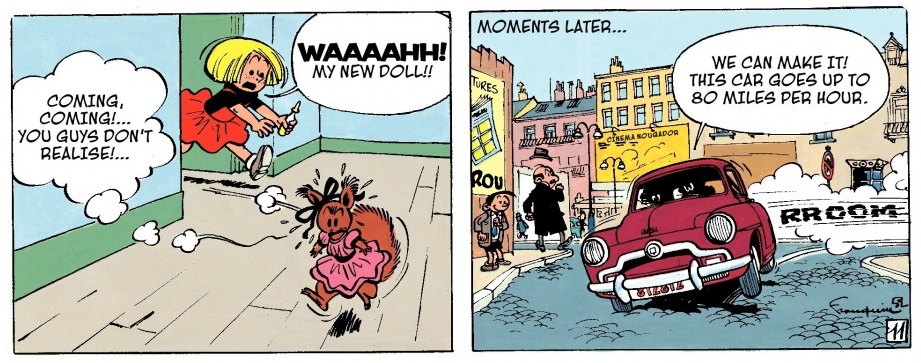

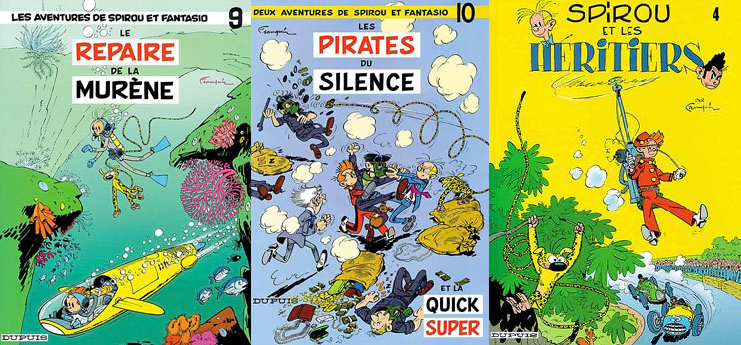

You can sense the joy in each drawing, particularly in the many extended scenes with the Marsupilami goofing around. This sort of stuff is clearly where Franquin’s heart truly was. Sure, he could pull off pulpy thrills, as proved in albums such as Le repaire de la murène [‘The Moray’s Hideout’], with its pre-Thunderball underwater action, and Les pirates du silence [‘Pirates of Silence,’ written by Maurice Rosy], where Spirou and Fantasio stumble into an ambitious heist on a secretive Jet Set city…

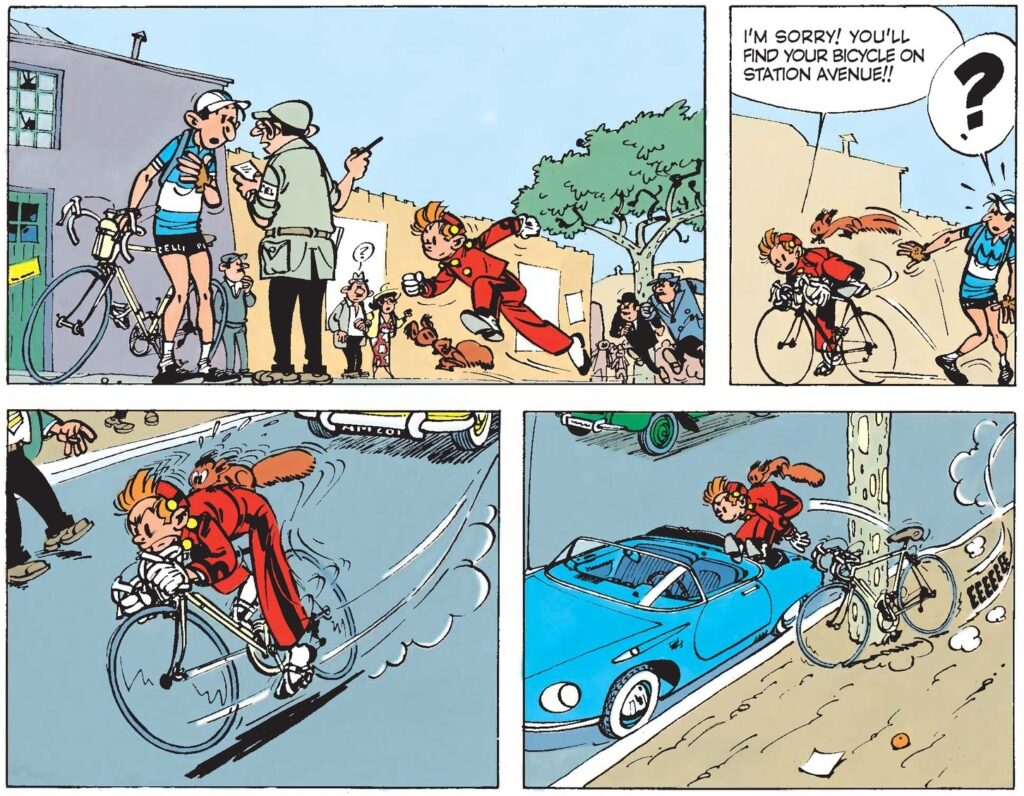

However, the more he established himself, the more Franquin turned out to be much less concerned with genre than with visual invention. Most of The Marsupilamis’ Nest – one of his strangest (yet amusing) albums – consists of a pictured documentary about the fictional animal’s eating and mating habits. Vacances sans histoires [‘Uneventful Holidays’] – which should be read right after The Marsupilamis’ Nest – is a loose short story where Franquin gets to indulge in the 1950s’ growing love affair with cars (it was a key feature of French society, as analysed in Kristin Ross’ fascinating book Fast Cars, Clean Bodies, and I don’t suppose car culture was all that different in the neighboring Belgium).

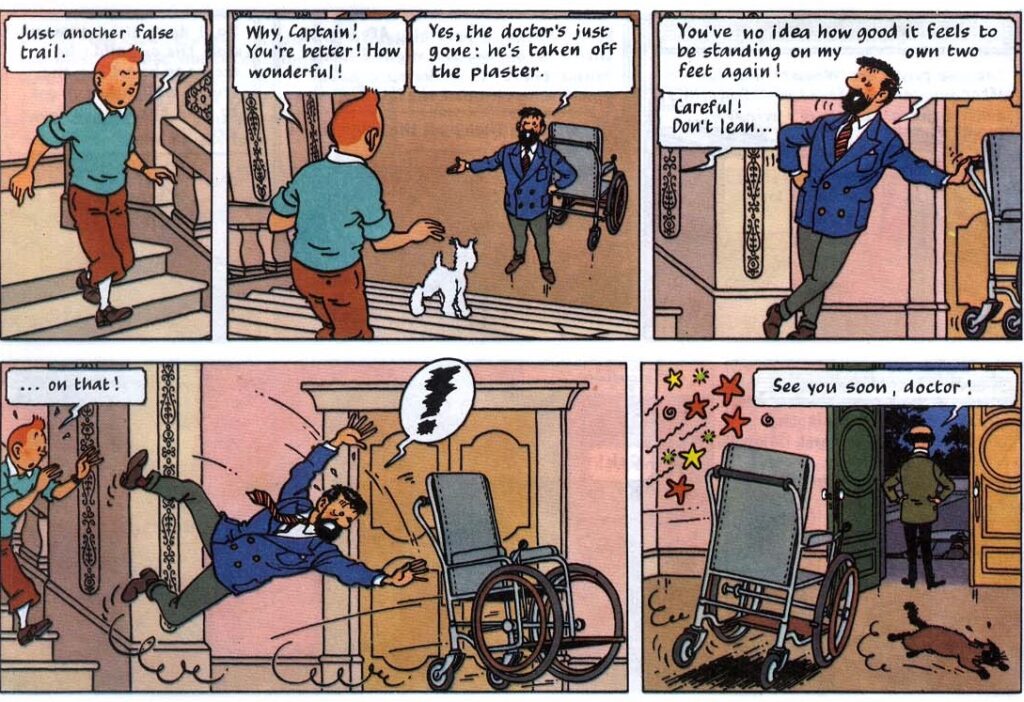

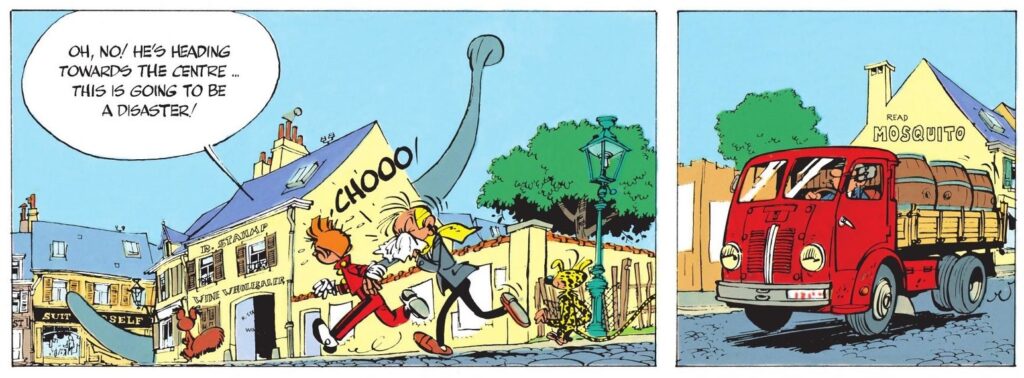

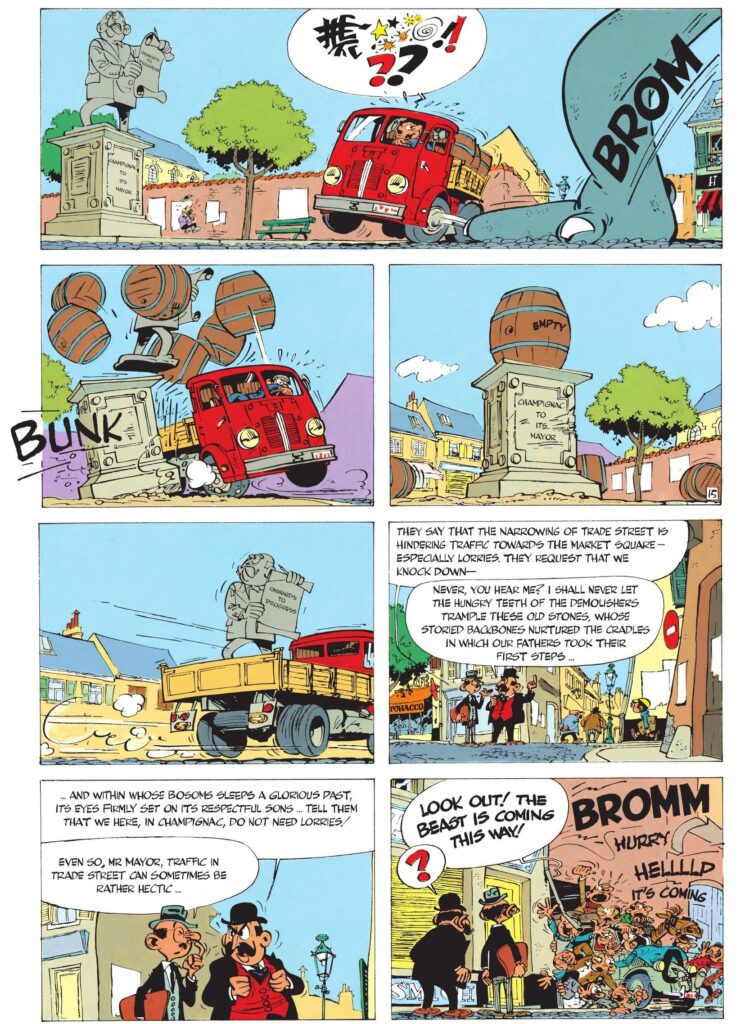

This tendency eventually reached an apex in the wonderful The Visitor from the Mesozoic, where Franquin unleashed a damn dinosaur in Champignac:

The Visitor from the Mesozoic

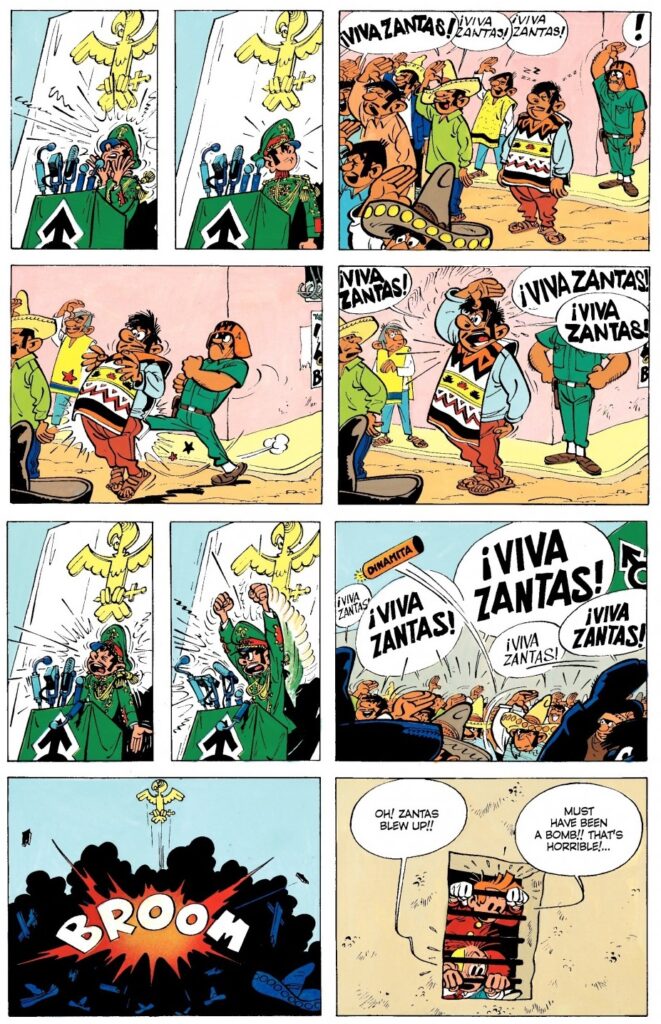

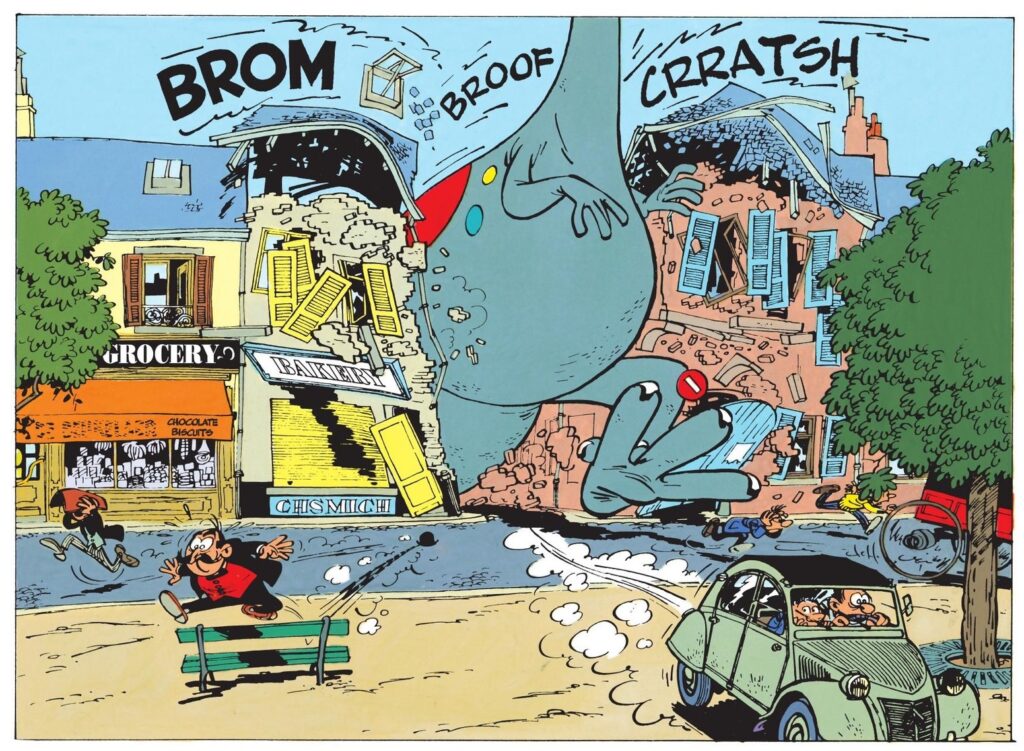

What makes The Visitor from the Mesozoic so special – and so quintessentially Franquin-esque – isn’t just that it forsakes Spirou & Fantasio’s (and Tinitin’s, for that matter) usual brand of intrigue in the name of escalating chaos, shamelessly replacing narrative with a barrage of funny moments…

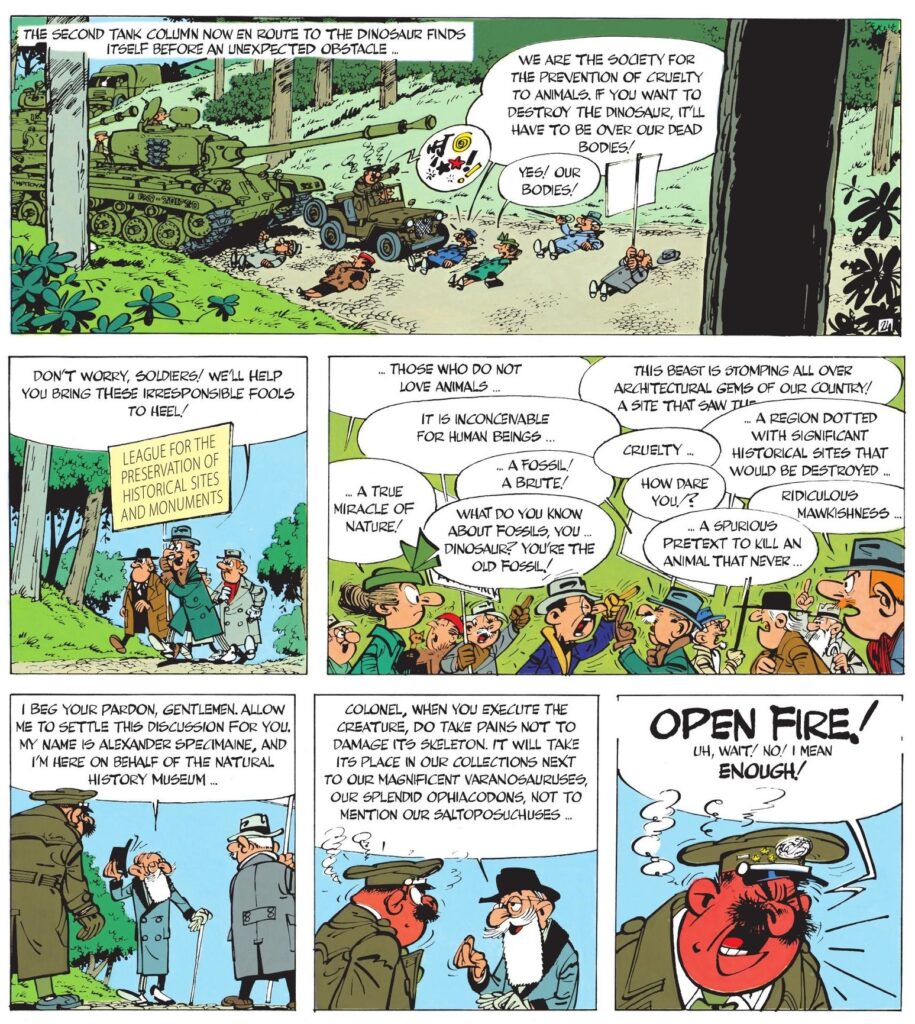

The thing is that, as you can see above, Franquin uses this Godzilla-like framing to trample over all sorts of authority symbols and figures. It’s almost as if the dinosaur represents Franquin’s own caustic id finally unchained and relentlessly smashing every institution that takes itself seriously.

The Visitor from the Mesozoic

Certainly Hergé never did anything remotely similar to The Visitor from the Mesozoic.

There is a delightful sense of freedom and iconoclasm to the whole thing. And, for a series that so far had mostly stayed away from an explicit engagement with politics, the book contains this priceless slice of cruel irony (where Spirou, appropriately, plays the straight man):

The Visitor from the Mesozoic

hey, I´m really enjoing these longer articles about european comics and looking forward to more!

That’s very nice to know! I actually have a bunch more of these I want to get to, whenever I find the time…

Thanks for the article, I really liked it. I stumbled upon it while looking for birthday present for my nephew. His mom told me he’s into comics now, he’s in second grade.

I remember being his age and going to the public library in town every couple of weeks and grabbing as many comic books as the library allowed to take home. Spirou and Fantasio were always among my favorites. I ordered the one with the car-race and the racecars on the cover as I think this is the first album I read and the one that got me hooked. Now that I look at your report, I definitely remember the first panel you posted. You called it fluidity. Look at the sheer amount of stuff happening in just a few panels! I really love the sense of speed conveyed when Spirou rounds that corner in that fast car. Part of it is obviously the speed lines that indicate the path of the car but even more so the composure and focus of the driver behind the wheel. Compare that to the lorry driver in the other panel who almost falls out of his seat trying to avoid a full frontal crash with the statue. It’s this sense of detail that makes these scenes stay in your memory even after 30 odd years. Great stuff.

You’re absolutely right that ‘speed’ is a key trait here… And besides making for some memorable comics that stand the test of time, I would argue that somehow this very sense of speed also situates them in a specific historical context, that of the burgeoning economy, technology, and consumerism of postwar Europe. I’ll probably develop this more whenever I get around to the rest of Franquin’s work on Spirou.