When I last wrote about The Unknown Soldier – DC’s cult comic about the top US secret agent in World War II – I mentioned how David Michelinie briefly turned the series into a vicious anti-war parable, casting the hero as an anti-hero and rendering the structural brutality of war as independent of each side’s morals. In 1977, however, when the series went back to one of its earliest writers, Bob Haney, he retreated into a more morally comfortable ‘just war’ mentality just in time for the feature to be promoted to the magazine’s leading title (i.e., the comic continued to be an anthology and even kept the numbering, but instead of Star Spangled War Stories, it was now called The Unknow Soldier).

As if to signal the shift in no uncertain terms, Haney penned his comeback story, ‘The Unknown Soldier Must Die!,’ as a full-blown reversal of the spirit of Michelinie’s recent run. Instead of an opening narration contesting war, the caption above the title explained that, even though soldiers feared and questioned every battle, they always fought ‘to gain the victory,’ for that was ‘their only true glory!’ The plot illustrated this point by condemning divisionism, as Chat Noir – an African American sergeant often partnered with the Unknown Soldier – was brainwashed by the Nazis, who used ‘his deep resentment… against the Amerikaners for treating him as an inferior person because of his color.’ After betraying the Allies and trying to kill the Unknown Soldier, Chat Noir eventually regained his senses, coming around to the fact that ‘for better or for worse, the States are my home… and home is always worth fighting, and if need be, dying for!’

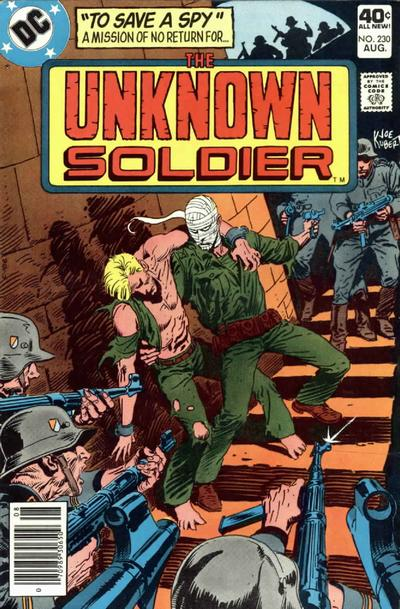

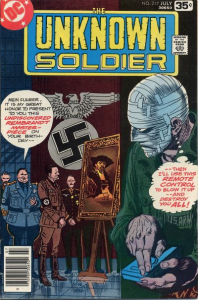

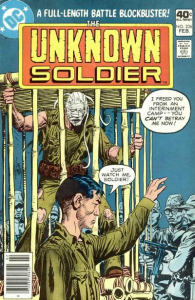

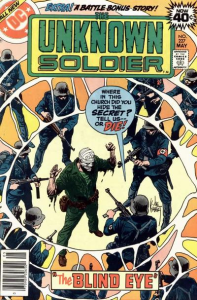

Gone was the Unknown Soldier who questioned his mission and regretted some of his actions, recognizing himself in the enemy. We now got tales of valor and righteous sacrifice, with the American military and their courageous allies outsmarting the evil Nazis and the sadistic Japanese, thus fighting for a freer world. (When Hitler showed up, he acted like an excited child.) The tone harkened back to a simpler era, as you can tell by the covers, which no longer featured the Unknown Soldier’s deformed face in the upper left corner – since he was back to being a straightforward hero, we no longer had to see his ugly scars. The real face underneath the bandages and disguises was also gone from the main images, where Joe Kubert typically depicted serial-style cliffhangers, often complemented with dialogue or thought balloons:

Bob Haney was quite at home here. A WWII veteran himself (he served in the Navy and saw action at the Battle of Okinawa), Haney had aleary penned tons of war comics since he had first joined the industry, back in 1948.

His second stab at The Unknown Soldier was still very much a product of its time, though. For one thing, it was clearly post-Civil Rights movement, both in the sense that it absorbed some of that movement’s lessons and in the sense that it deliberately tried to move away from its more radical implications. On the one hand, Chat Noir’s recurring presence could be seen as progressive, given that he was a resourceful and outspoken black character at a time when there weren’t all that many in comics. On the other hand, he ended up fulfilling the reactionary role of the black sidekick who legitimized the white lead (and in the process, despite sporadic complaints, underplayed the segregation in the US forces during WWII).

Above all, however, this was a post-Vietnam War comic, seeking consolation for the recent defeat – and for the moral doubts ushered in by that conflict – by revisiting a war that could be seen as a source of pride rather than a source of shame and frustration (the same went for backups like Robert Starr, Frogman and Andy Stewart, Combat Nurse). In other words, by the late 1970s, The Unknown Soldier’s World War II was no longer a metaphor for Vietnam but, at its best, nostalgic escapism and, at its worst, a militaristic fantasy about winning with the proper support.

I don’t mean to say the series anticipated the kind of nationalist super-soldiers played by Sylvester Stallone and Chuck Norris in the Reagan era. Rather, like Haney’s earlier comics, this run feels like a throwback to the propagandistic thrillers the Allies put out during WWII. (For instance, one of my favorite stories, ‘The Savage Sea!,’ is a small whodunit set in a convoy that brings to mind the Bogart movie Action in the North Atlantic.) This means that, yes, there is a clear message about the need for unity and war, but it tends to be mixed with an almost perverse sense of excitement and entertainment, as the Unknown Soldier fights a sumo wrestler, performs a daring escape by posing as a circus acrobat, and keeps resorting to all sorts of surprising disguises:

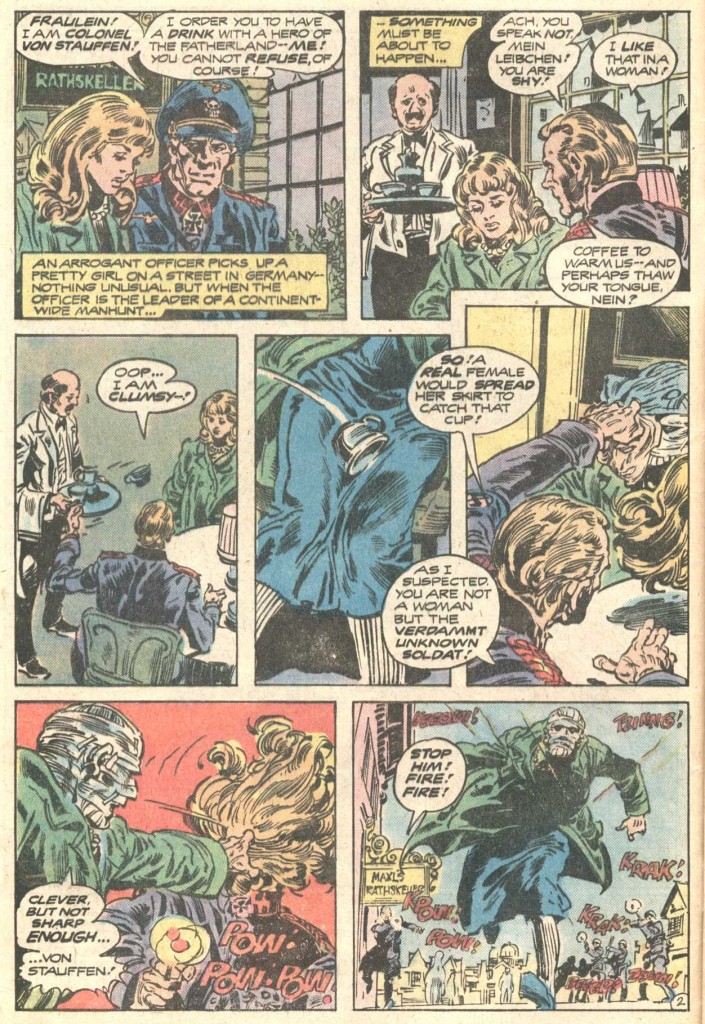

The Unknown Soldier #218

The Unknown Soldier #218

Hell, Haney even introduced a recurring foe, Major Klaus von Stauffen (aka the Black Knight), who owned up to the idea that this version of the war was ultimately a game, with the whole of Europe serving as a kind of huge board for a real-life chess match against the titular gauze-shrouded super-spy. This led to a preposterous puzzle-like plot in which Chat Noir and the Unknown Soldier found a cryptic clue in Paris, quickly moved to Normandy, and then, based on a guess, immediately went to England, constantly bumping into the Black Knight along the way. But hey, if you’re willing to forgo logic and realism and just throw yourself into the story (which is usually the best way to read Bob Haney’s comics), it’s a thrill-a-minute ride!

That said, having firmly reestablished the series’ gung-ho approach to WWII adventure, Haney wasn’t afraid to gradually mess with the formula. Some of his stories did complicate the conflict’s politics, even if mostly as grist for drama that typically culminated in the reaffirmation of a larger sense of duty. ‘An Honorable Betrayal?’ acknowledged (albeit with disturbingly pragmatic resignation) that the internment camps for Japanese-Americans were ‘no way to treat people’ and briefly presented a more understanding look towards treason and empathy with the enemy. In ‘No Exit from Stalag 19!,’ a bunch of POWs in a Czechoslovak camp agreed to work on a Nazi infrastructure project, reasoning that they were ultimately contributing to eventual post-war prosperity (a subchapter had the cheeky title: ‘Barbed Wire is Neutral!’). Yep, it was The Unknown Soldier’s version of The Bridge on the River Kwai.

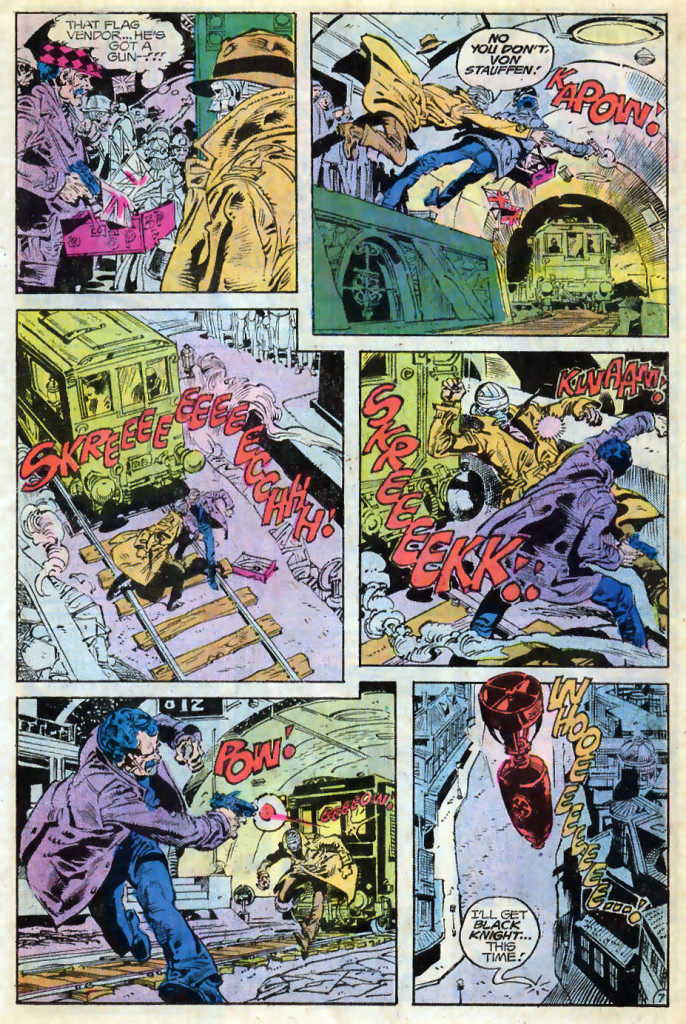

Regardless of the ideological slant, I admit I have a lot of time for Bob Haney’s sheer sense of spectacle. Each tale burst with chases, shootouts, and explosions. There were elaborate passwords, ingenious secret codes, and reworked set pieces from famous movies (‘The Invisible Traitor!’ borrowed one from Alfred Hitchcock’s Foreign Correspondent, ‘Mission: Incredible!’ seems inspired by the premise and ski action of Anthony Mann’s The Heroes of Telemark). Practically every page had a death-defying stunt or a switcheroo. The narrative usually began in media res and, after a brief expository flashback, the Unknown Soldier – or, as Haney’s narration sometimes called him, ‘the Immortal G.I.’ – hardly ever stopped moving…

The Unknown Soldier #207

The Unknown Soldier #207

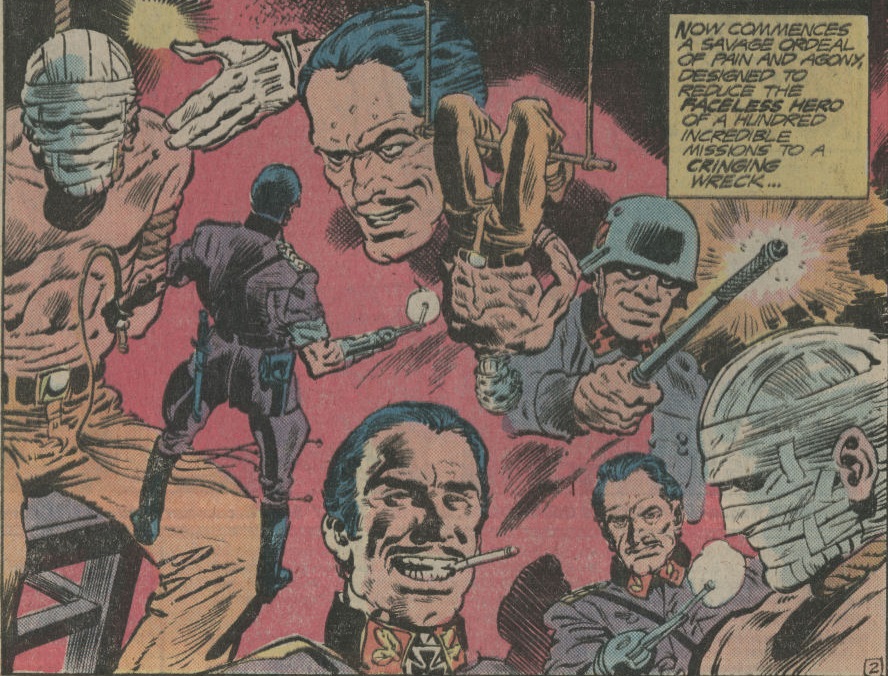

Well, I suppose he did stop for the occasional moment of patriotic contemplation… and, of course, during those countless times when he was being ruthlessly tortured…

The Unknown Soldier #231

The Unknown Soldier #231

For the comic’s sense of restless momentum, you should especially thank the art team of penciller Dick Ayers, inker Gerry Talaoc, and colorist Jerry Serpe, who always brought to the surface the contagious liveliness required by Haney’s frantic scripts. Securing a visual continuity with the previous run, Gerry Talaoc, in particular, imbued the artwork with a compelling, not-quite-cartoony style. (To appreciate Talaoc’s impact, compare his issues with those inked by Romeo Tanghal, which are rendered much more blandly.)

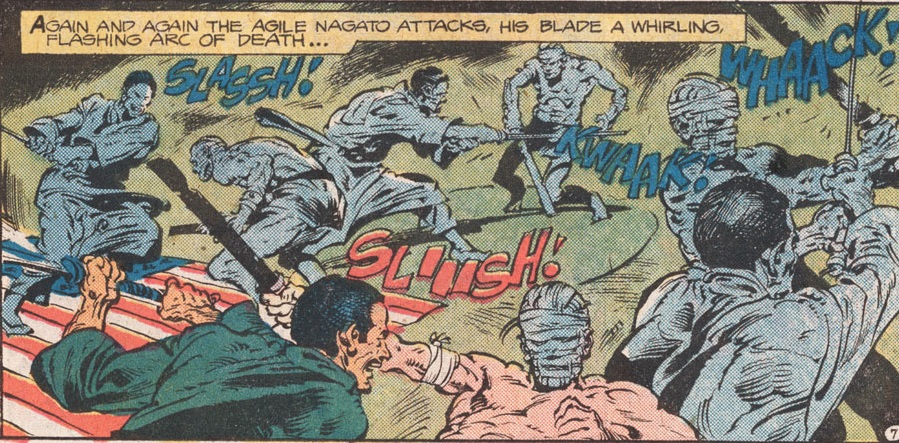

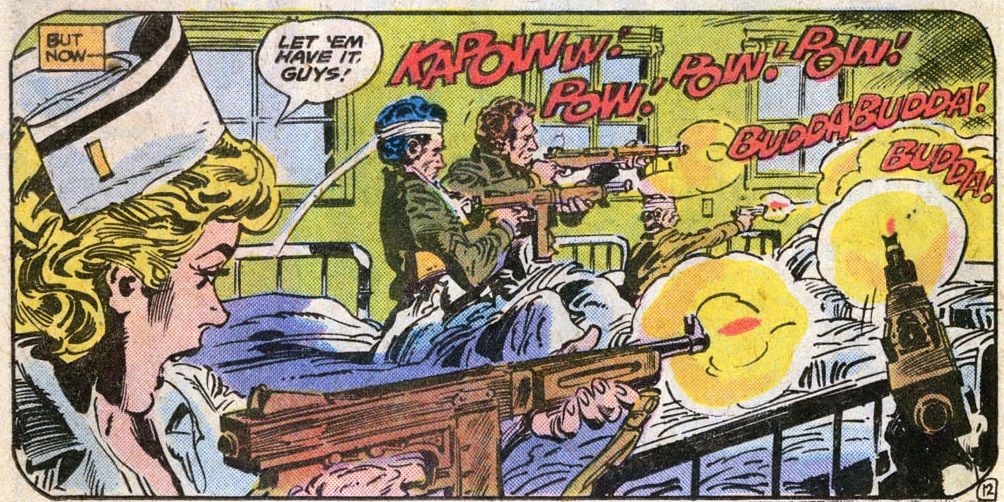

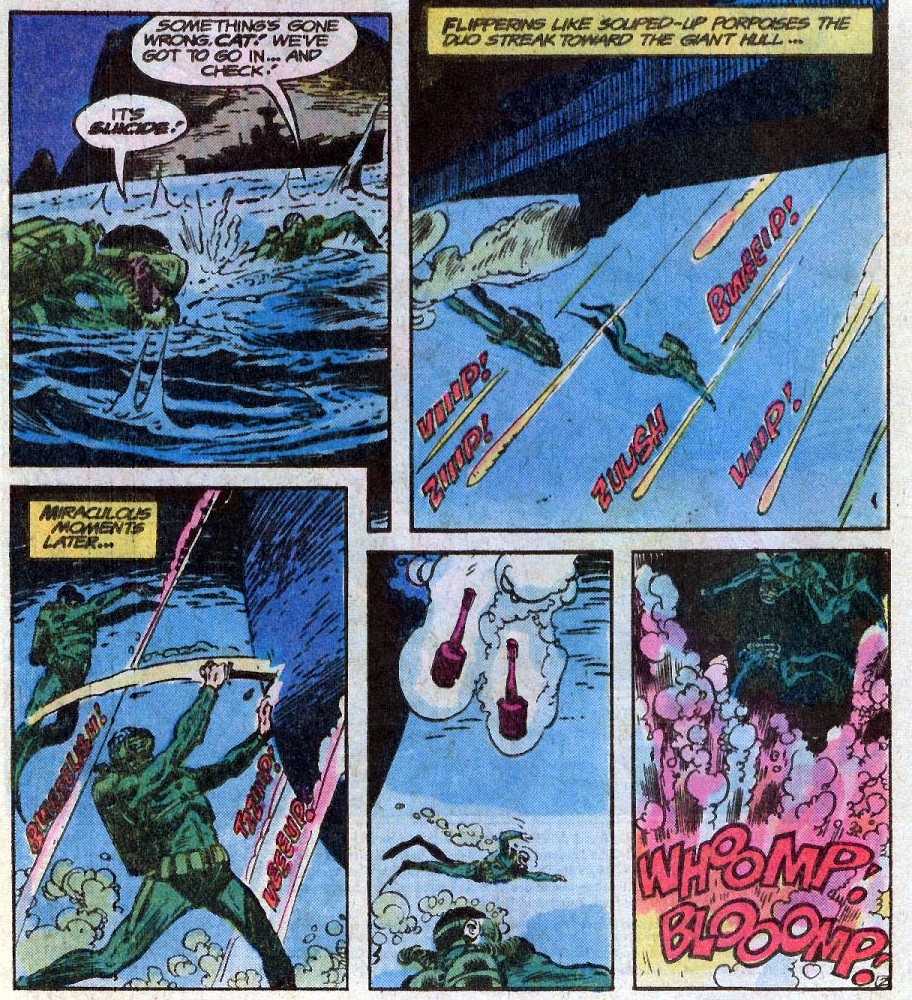

Also, I assume letterers Erick Santos Jordan and Esphid Mahilum provided the bombastic sound effects, which helped nail the action beats:

The Unknown Soldier #209

The Unknown Soldier #209

The Unknown Soldier #212

The Unknown Soldier #212

The Unknown Soldier #226

The Unknown Soldier #226

Again, you can spot Erick Jordan’s and Esphidy’s contribution by comparing their work with that of guest letterers like Milt Snappin and Jean Simek, who didn’t deliver the same oomph:

The Unknown Soldier #214

The Unknown Soldier #214

The best story of the lot is probably ‘Sunset for a Samurai!,’ in which the Unknown Soldier infiltrates Japan (yes, this means resorting to yellowface, although fortunately Jerry Serpe’s palette is relatively restrained in this one) to meet a local double agent torn between contradictory loyalties. That comic feels like a whole blockbuster crammed into sixteen forceful pages packed with battles, twists, traps, mysteries, McGuffins, and high drama.

I also have a soft spot for ‘Get the Desert Fox!,’ which amusingly turns real-world General Erwin Rommel into a full-on comic book villain. That one has a hell of an opening:

The Unknown Soldier #229

The Unknown Soldier #229

Given the title of this blog, I would be remiss if I didn’t mention that the Unknown Soldier also teamed up with Batman in ‘The Secret That Saved a World!’ (The Brave and the Bold #146, cover-dated January 1979). By then, it had been amply established that Bob Haney’s version of the Caped Crusader had been active during WWII, so the writer built on this idea by having Batman investigate a ring of Nazi saboteurs in Gotham City, which led him to none other than Klaus von Stauffen (who had come to the US to spy on the atomic program). The climax involved the Unknown Soldier posing as President Roosevelt!

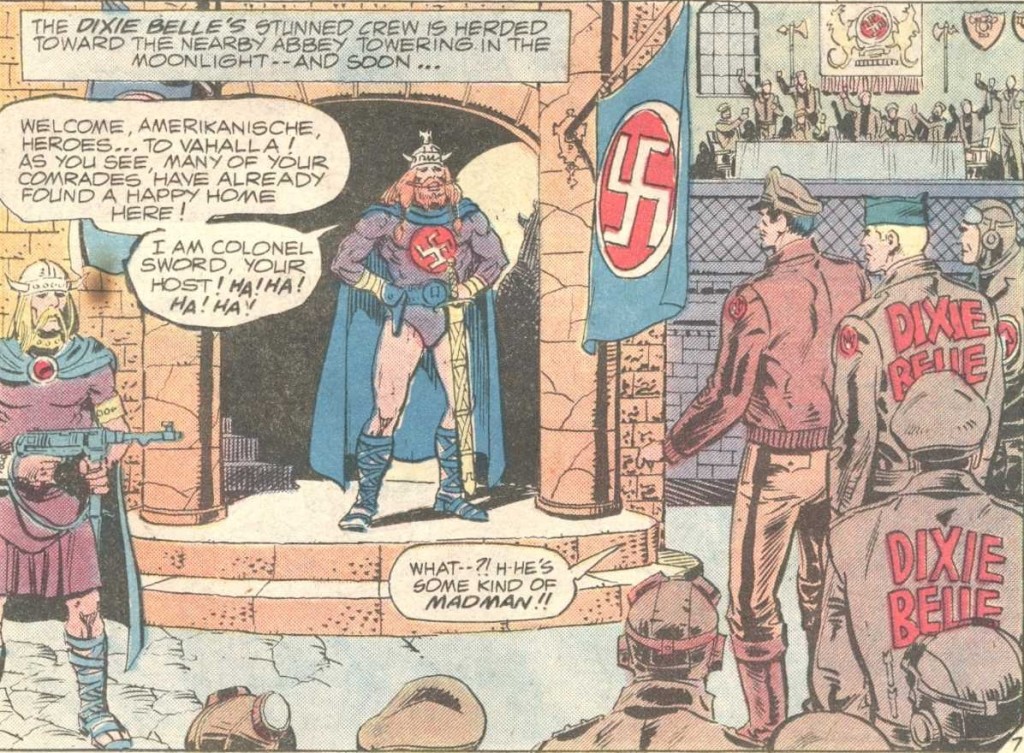

That tale eventually led into the epic ‘Jungle Showdown!’ (The Unknown Soldier #234, December 1979), which not only featured our hero fighting an alligator, but it finished off with him trapped in an exploding airplane! It’s a pretty awesome issue, although perhaps not as much as the issue where the Unknown Soldier came across yet another brainwashing operation, this time run by Nazi Vikings:

The Unknown Soldier #224

The Unknown Soldier #224

I suppose Haney could only write the comic for so long before giving in to his flair for delirious bizarreness… It’s why his run’s final years deserve their own post, some other time.