At a time when pavlovian pundits and politicians seem keen to revive Cold War rhetoric and imagery, (mis)applying it to the conflict taking place in Ukraine, perhaps it is worth remembering that even during the Cold War itself there were dissident voices who rejected the mindset of simple bipolarity. With that in mind, let’s look at one of the angriest Cold War-set comics from that era:

I’ve written before about The Unknown Soldier’s original comics – especially Bob Haney’s epic runs – and how their tales of WWII military spy adventures speak to different understandings of war in general and of US foreign interventions in particular. This political angle was there from the start, but it became front and center when editor Denny O’Neil, writer Christopher Priest (then known as Jim Owsley), and artist Phil Gascoine resurrected the character for an unabashedly blunt 12-part series in 1988-9, which I love to pieces.

The project was clearly part of the post-Dark Knight Returns wave of comics reimagining old properties with a more violent, morally ambiguous lens that did double duty as political commentary. In particular, it belongs to the set of hyper-cynical spy books put out by DC at the time, including Justice, Inc. (which had pretty much the same premise of a chameleonic secret agent), Checkmate!, the revamped Blackhawk, and the more superhero-y Suicide Squad. In the case of this version of The Unknown Soldier, the comic put a twist both on the character’s previous series and on its war-related themes.

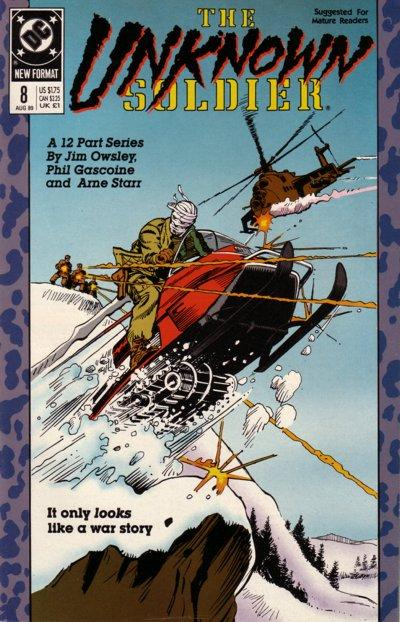

Before looking more closely at this run, let me make it clear that there is not a trace of subtlety to be found here. Like with the works of Alan Grant, Pat Mills, and Jack Kirby (hell, even much of Will Eisner’s), a lot of the pleasure derives precisely from the heightened bile and verve, as they make each point as forcefully as possible. Christopher Priest and the famously anti-militaristic Denny O’Neil never try to hide or nuance the fact that they are taking the character and formula of a war comic and putting them in the service of an anti-war comic. As you can see above, they warn you on the tagline of every cover: we’ll give you thrills, but if you’re looking for a Rambo-like product, you can just fuck off.

This brazen attitude could’ve been annoying (perhaps it is, for some readers), but the creators actually make the book’s spirit feel gripping and contagious, as they fire on all cylinders from the get-go. Indeed, this series grabbed me from the very first page:

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #1

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #1

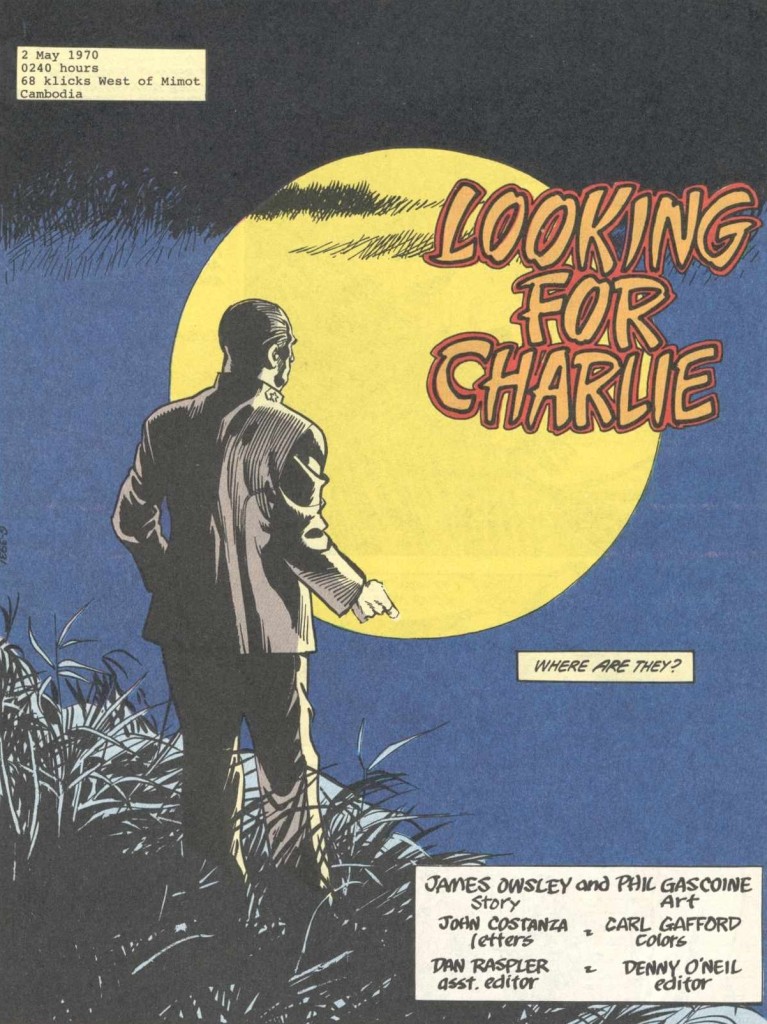

There is something cinematic about the framing, with a man’s silhouette poised against a full moon, slightly obscured by blurry clouds. It’s a still, apparently quiet image, so where does the dynamism come from? Perhaps it’s the fact that the moon’s geometric perfection feels disturbed by the scratches at the top and the wild vegetation at the bottom. Or perhaps it’s Carl Gafford’s palette, with the bright spot in the middle encroached and pierced by the surrounding darkness (which, as we’ll find out, fits in with the comic’s themes).

Veteran letterer John Costanza helps set up the tone: while the caption localizing the scene, with its raw data and military jargon, is done with a with a typeset font suggesting a report, he renders the question in the other caption with a more conventional comic book font, including an emphasized word, reinforcing the contrast between cold precision and human uncertainty… because, as we can intuitively tell, the question stems from the man’s mind (this, in itself, is also suggestive, as using isolated rectangular captions rather than thought-balloons is a convention associated with coolness). In turn, the title (more military slang) and the credits bring to mind East Asian calligraphy, promising us a globetrotting yarn.

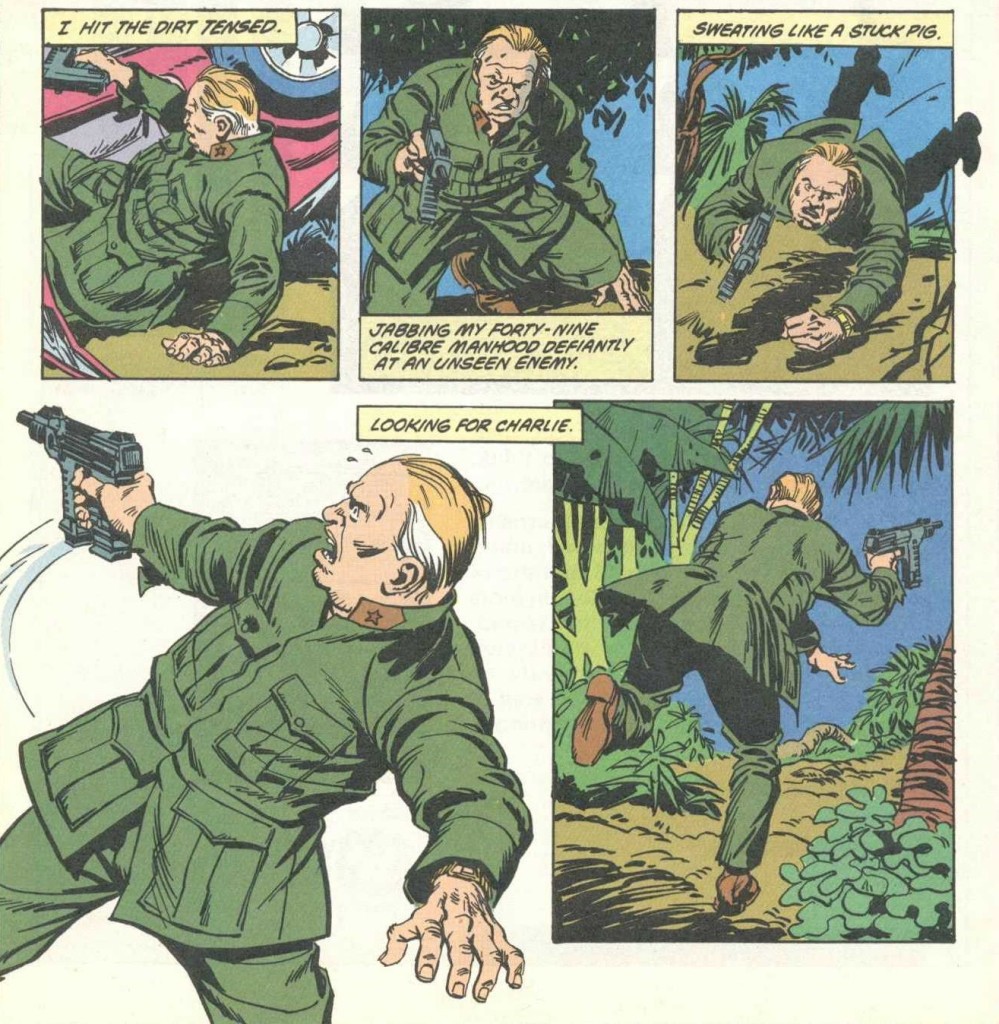

We are in the Vietnam War, following a gun-smuggling operation in Cambodia, which the Unknown Soldier is trying to bust. He is disguised as a Soviet colonel and the first time we see his (fake) face is in the mirror, accompanied by some sarcastic thoughts about his mission (‘After all, if Charlie has guns, it makes it tougher for the good guys to march into his back yard and kill him.’). The themes of identity crisis and murky politics are all in place, as is the Unknown Soldier’s terse, disenchanted inner voice. Soon, we are thrown into an all-out action set piece, which justifies the story’s title:

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #1

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #1

The rest of the series, which jumps back and forth in time to various assignments throughout the Cold War, keeps this sort of relentless momentum, throwing the Unknown Soldier into missions he despises and then watching him desperately struggle through danger and violence while insulting his superiors in his head. It never gets boring, not least because the geographical setting and time period keep changing, not to mention the Unknown Soldier’s appearance, making the most out of the fact that he is a master of disguise (as well as, implicitly, a master polyglot).

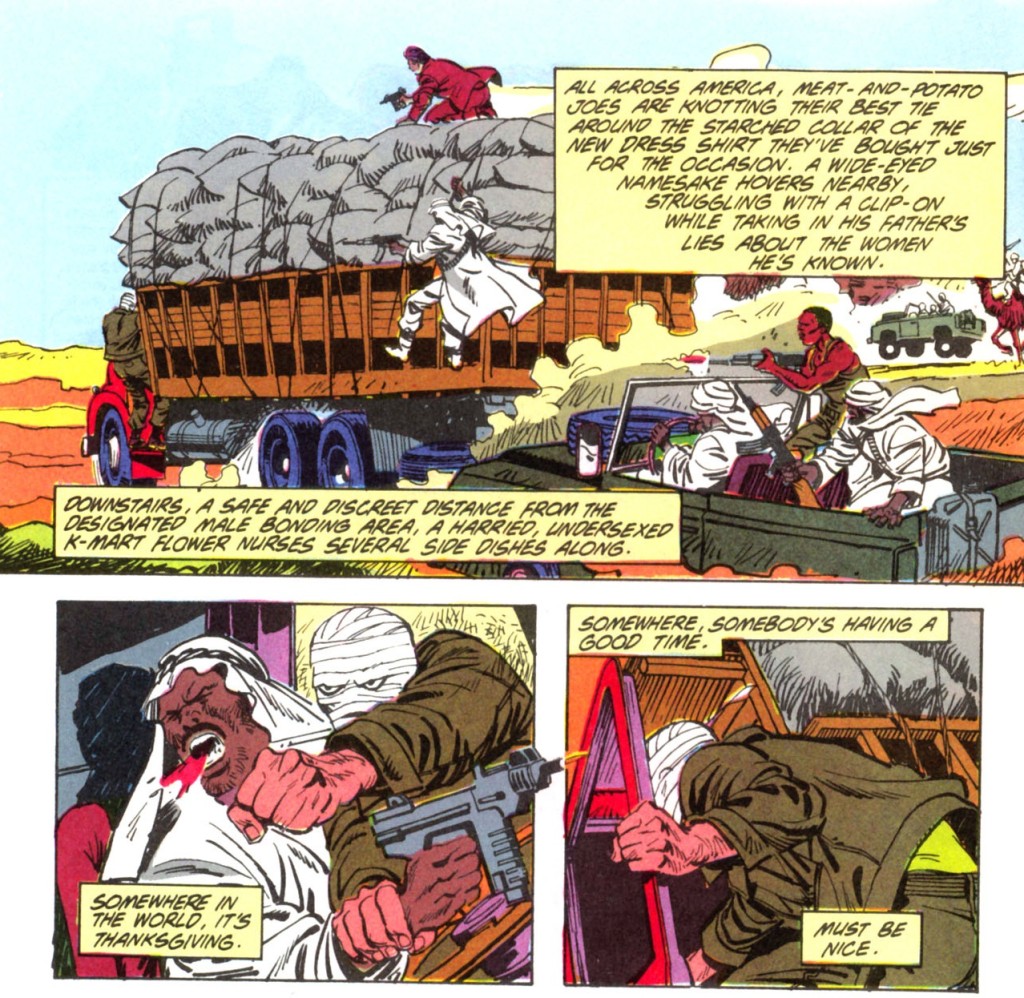

Each issue opens with a knockout image and/or line. So, for example, issue #9 gives us a North Korean platoon in the middle of the Korean War and you just know one of the soldiers is probably our protagonist, who is thinking: ‘Douglas MacArthur was never my friend.’ The last issue is even more extreme, with a chaotic sequence that visually suggests we have just walked into the heart-racing climax of an ongoing blockbuster, in clear contrast with the Unknown Soldier’s calm – if typically sardonic – narration:

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #12

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #12

Although most stories are standalone and do not end on a cliffhanger, the blurbs promoting the next issues are also a blast. One of them promises ‘violence and mystery and violence and intrigue and violence and romance and violence and food.’

Such comedic outbursts, when aligned with the series’ frantic pace, social-conscious themes, and the premise of a chameleonic action hero in a constant state of identity crisis, make The Unknown Soldier feel like an ancestor of Peter Milligan’s brilliant Human Target comics. It even has the kind of twisty plotting Milligan excels at – for instance, in the fourth issue, we follow three mercenaries in Honduras and we know one of them is the Unknown Soldier, but not which one, so the result feels both like a brutal thriller and like a neat mystery.

And sure, Milligan’s writing tends to go for a more ironic distance, but, like said, here too there is sometimes a tongue-in-cheek element to the proceedings. For all of its political critique and righteous indignation, The Unknown Soldier is not without a sense of humor…

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #6

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #6

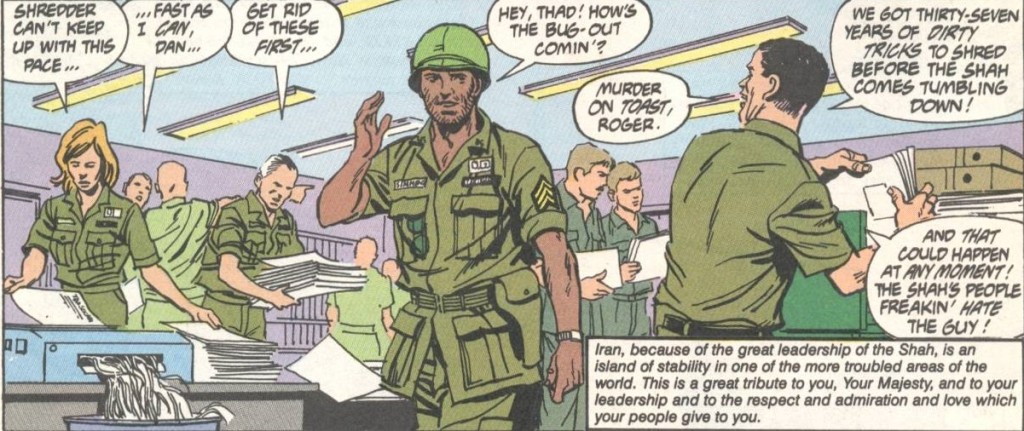

Hell, the two tendencies occasionally meet for some gleeful in-your-face satire, like in the opening of the second issue, which juxtaposes Jimmy Carter’s ‘Island of Stability’ speech with this scene at the American Embassy in Teheran, in late 1977:

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #2

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #2

For the most part, though, I admit the message is presented in quite earnest terms. When the Unknown Soldier’s inner narration isn’t condemning the United States’ obstinate anti-communist foreign policy, it’s because it’s denying even the sense of a committed, if misguided, ideological motivation behind the whole Cold War enterprise: ‘I wonder if the people who live in Central America suspect that no one gives a damn about them. The soldiers care about their strategic position. The politicians care about getting re-elected. Some of the rebels are more interested in running drugs and getting it on than they are in liberating their people.’

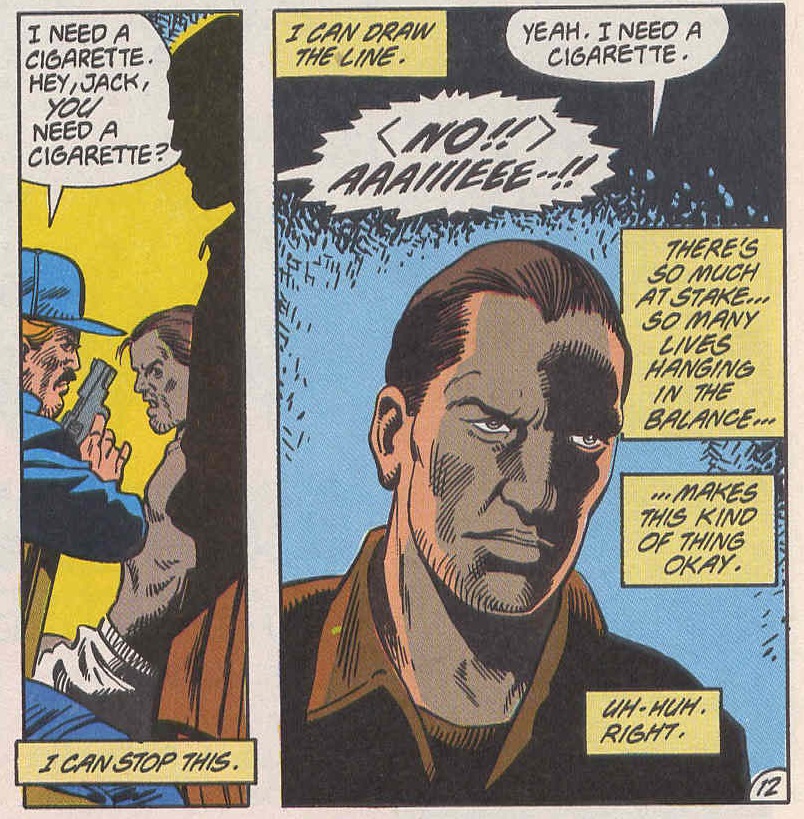

Even when the series resorts to the Jack Bauer-ish trope of justifying torture in the name of preventing an imminent terrorist attack, you can see the Unknown Soldier struggling with his conscience (although, hypocritically, he does play along, as usual):

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #7

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #7

(The guy doing the torturing is a cynical CIA agent named Barry who, in my head cannon, is totally Green Arrow’s Eddie Fyers!)

The series’ leitmotif is the notion that the Unknown Soldier, after so many years impersonating the alleged enemy, has learned to see US interventionism through the enemy’s eyes. It’s not just that he realizes the fundamental truth that even the heroes are ultimately the villains if seen from the point of view of their opponents… No, he realizes that his country’s imperialist policies are indeed despicable and dictated by utter bastards.

Seriously, don’t underestimate how radical these comics are. When the Unknown Soldier goes to Afghanistan in the early 1980s to support the Mujahedeen, he ends up sympathizing with the Soviet invaders…

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #3

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #3

For all these reasons, the series is definitely worth a look, especially as the whole thing works pretty well on its own, with absolutely no need for readers to have even gazed at the previous Unknown Soldier comics (of which there were over a hundred). If you’ve read those, though, there is an extra layer of interest in the various ways Priest radically revises the franchise, which are deeply interconnected with the series’ Cold War historical revisionism. This point has already been argued here, but I think some sequences still deserve a closer reading… This will be the focus of next week’s post.