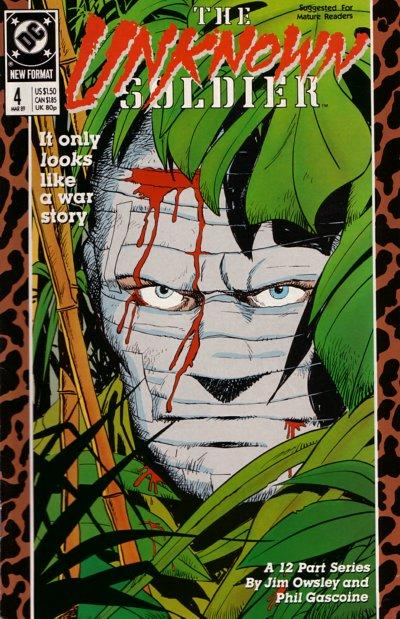

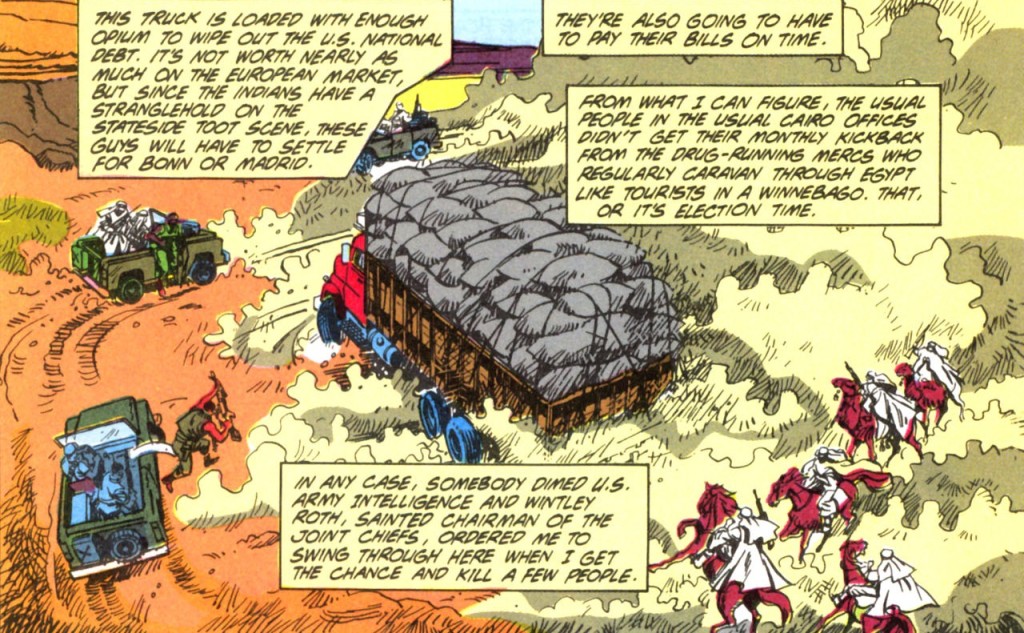

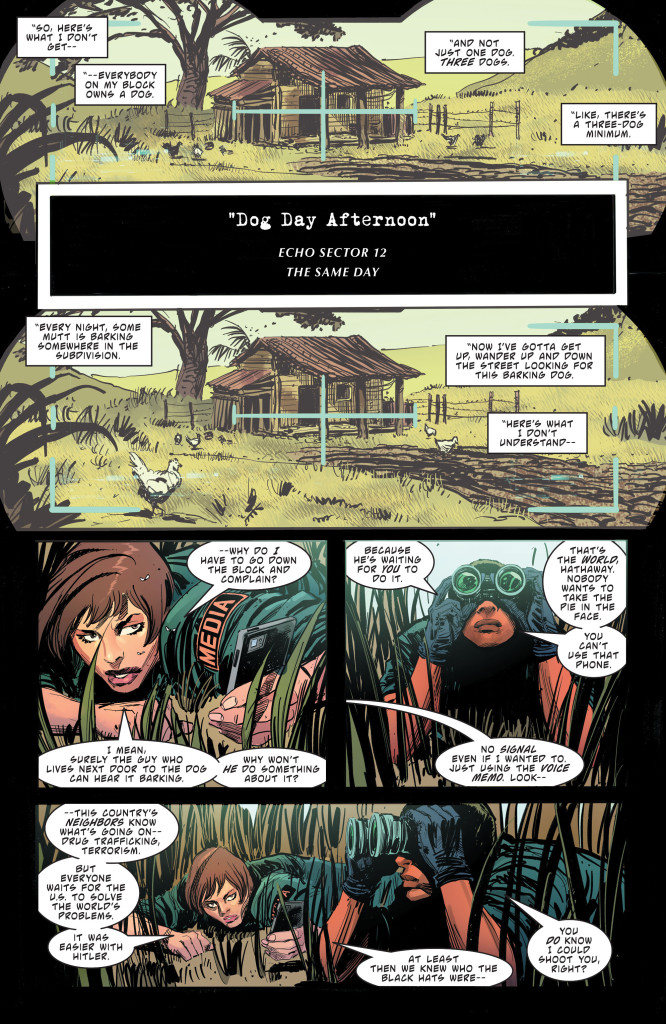

As I started to discuss last week, 1988-9’s exhilarating The Unknown Soldier limited series is miles apart from Joe Kubert’s original iteration of the character. For one thing, instead of a fully-committed agent of an unquestionably righteous American war effort, this version of the Unknown Soldier is a highly conflicted and increasingly frustrated anti-hero who often voices a harsh critique of the moral compromises that come with armed conflict and espionage. At best, he views his assignments with utter cynicism:

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #12

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #12

Still, there was a precedent for all this. Archie Goodwin, Frank Robbins, and even (sporadically) Bob Haney all wrote their fair share of anti-heroic moments into the Unknown Soldier’s saga, a tendency that was taken to the extreme during the David Michelinie run of the mid-1970s (as spotlighted here). For example, here is the ending of the two-parter that ran in Star Spangled War Stories #186-187 (cover-dated April-May 1975), about a particularly vicious mission involving dead children and the murder of a well-meaning priest… and which turned out to have been in vain:

Star Spangled War Stories #187

Star Spangled War Stories #187

As you can see, Christopher Priest’s characterization is not all that inconsistent with the past, especially if we take into account that we are looking at an older version of the Unknown Soldier, who has been through a lot and is understandably getting more and more sick of the endless march of war.

Visually, there is also a great deal of continuity, even if the original character was generally depicted as a taller, more imposing figure (when he was not in disguise, of course). Priest and artist Phil Gascoine did away with the preposterous notion that the Unknown Soldier wrapped his face in bandages as a default look and wore his perfect masks over those bandages… Instead, he is now shown normally wearing a fabricated face and, at first, we only see the bandages in his imaginary reflection when he is contemplating his darker side. Later in the series, he starts wearing the bandages more regularly, perhaps because this is such a distinctive – and cool – feature of the property (which also explains why he is shown wearing them in every cover).

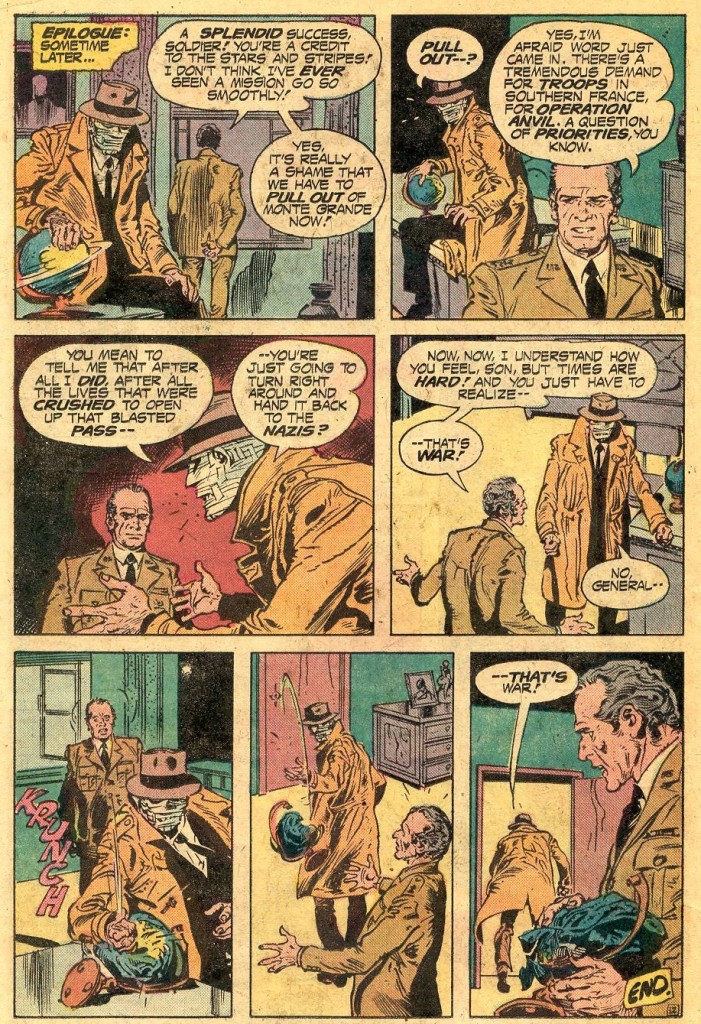

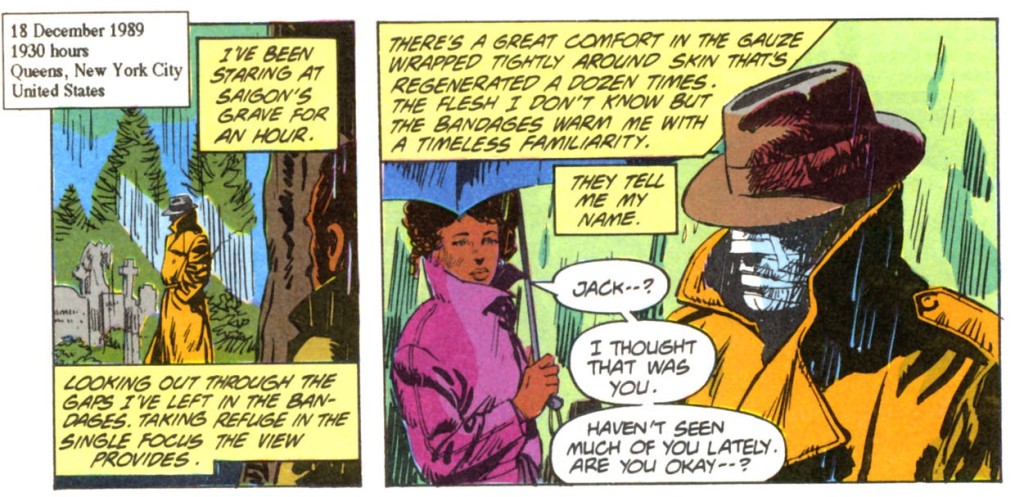

The biggest change to the Unknown Soldier himself is that he was now given super-strength and a Wolverine-like healing factor, thus literalizing the ‘Immortal G.I.’ nickname used in the old comics (and justifying the fact that a WWII vet was still kicking butt in the late 1980s). The element of immortality obviously had a toll on the character’s psychology, his constant regeneration ironically giving him more of a world-weary core. I love how Priest addresses this in a few passages that even manage to imbue a deeper meaning into the bandaged-face gimmick:

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #12

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #12

This is not to say the series follows the same continuity as the earlier stories – it’s definitely a reboot, but it does leave a lot of room open to incorporate the Unknown Soldier’s previous adventures. There is even a cameo by the former supporting character Chat Noir during a flashback to World War II, in issue #6, although it feels more like a nod to the fans than like proper piece of continuity, if nothing else because the original character wasn’t actually called Chat Noir (this was just a codename he had picked up after joining the French Resistance). That said, Christopher Priest, who is famous for his concern with racial representation in comics, does introduce two new sympathetic African-American cast members, including Roger Simmons, who becomes the Unknown Soldier’s closest friend, effectively taking the place of Chat Noir…

(Curiously, though, there is never a clear response to the fact that, while there were several stories about race in the original (for example, ‘No God in St. Just!,’ The Unknown Soldier #237), they mostly boiled down to the notion that black people should set aside their concerns with American racism and privilege the fight against foreign enemies, the subtext being a subordination of divisive Civil Rights struggles to the Cold War consensus.)

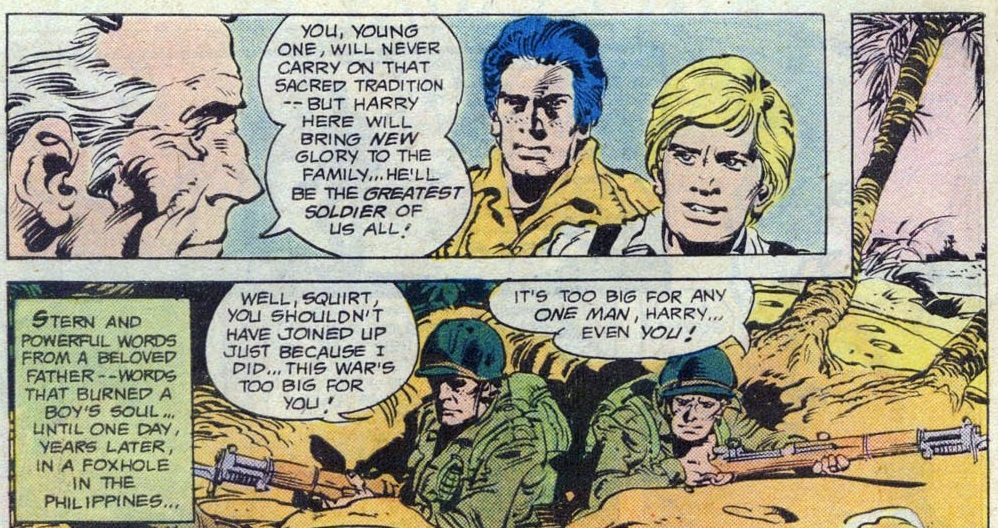

What makes this a reboot, above all, is the radical revision of the Unknown Soldier’s origin. His origin tale, which had been told multiple times by Joe Kubert and Bob Haney, used to boil down to two key aspects. One of them was the fact that his father motivated him and his brother, Harry, to fight in World War II by educating them about their family’s proud tradition of fighting in the United States’ wars, going back to the American Revolution…

The Unknown Soldier #205

The Unknown Soldier #205

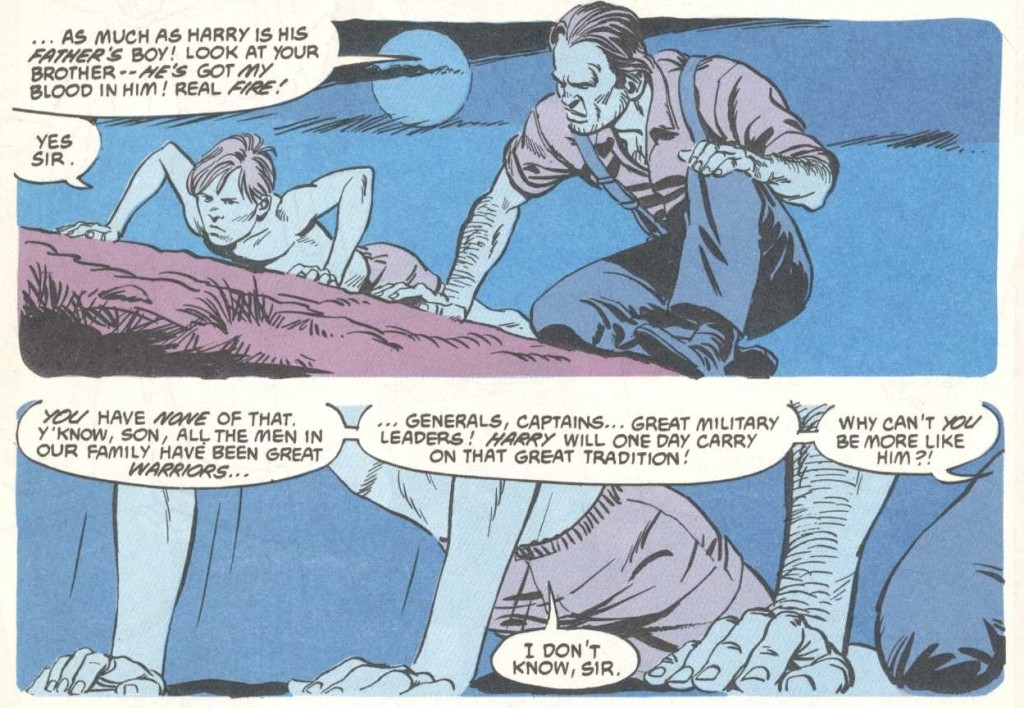

In line with the ‘anti-war’ stance of Priest’s The Unknown Soldier series, the reboot turns this premise on its head by cleverly keeping all the core ingredients while shifting the father’s posture (and thus the whole discourse about belligerent nationalism) from benign teacher to sinister drill instructor:

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #1

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #1

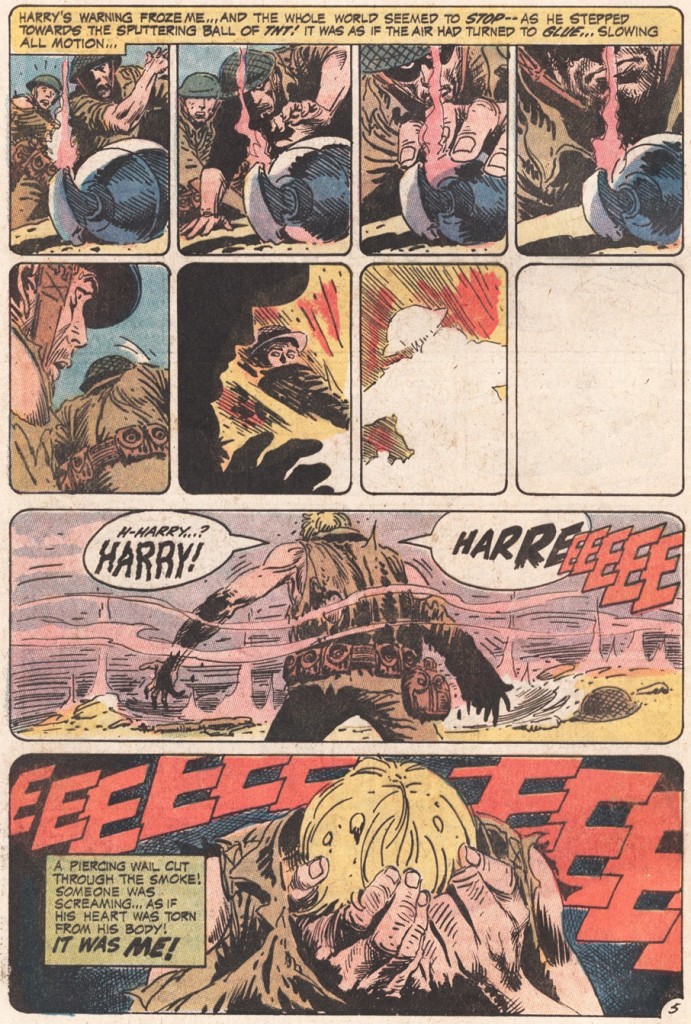

The other foundational moment took place in the Philippines, where, according to the previous accounts, Harry had bravely sacrificed himself, jumping over the grenade whose explosion nevertheless disfigured the future Unknown Soldier, inspiring him to carry on the struggle… This scene was depicted numerous times, but never in a more epic form than in Joe Kubert’s first rendition, which shifted from a wide splash to a set of tiny panels, slowing down the time to convey the historical importance of what was taking place before culminating in two powerful horizontal panels that showed the birth of the (previously hesitant, yet henceforth intrepid) faceless Unknown Soldier:

Star Spangled War Stories #154

Star Spangled War Stories #154

Again, the 1988 version keeps the basic outline while dramatically turning the tone and message upside down. Instead of an honorable sacrifice, Harry’s death is now the pointless product of a mental breakdown. To drive the contrast home, Phil Gascoine’s four-panel tiers even look like a deadpan parody of Joe Kubert’s original layout:

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #1

The Unknown Soldier (v2) #1

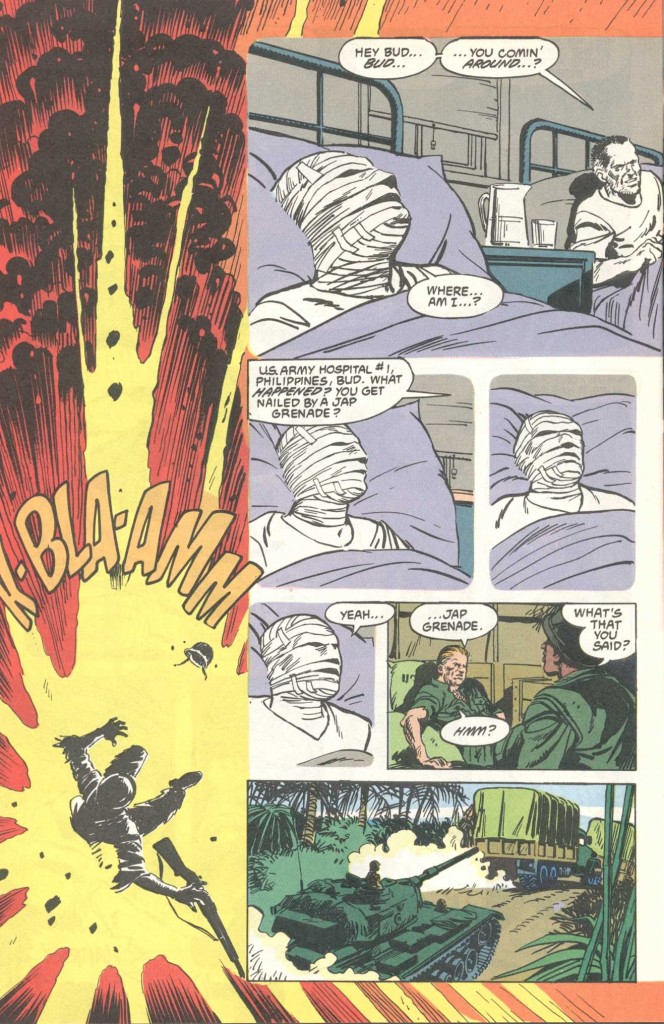

The page above is near perfect. Gascoine draws the explosion as a bleed that takes over the whole background, which makes sense because the explosion does – and will – remain in the back of the Unknown Soldier’s mind. The dialogue is provocatively ambiguous, since the protagonist’s lying answer about the Japanese grenade insinuates that perhaps what we’ve seen in the previous series was actually the version of reality the Unknown Soldier told others (and himself?) in order to cope with what happened…

Besides being quite a revisionist twist, such a reading also works thematically: the lie, although presumably told for personal reasons, is completely in tune with the Army’s reputation for whitewashing its self-inflicted casualties, so it fits into the overall propaganda about the heroic nature of World War II, which was later used to justify further foreign interventions. This allegorical interpretation is reinforced by the transition, in the lower half of the page, from the WWII era to the Vietnam War (where the Unknown Soldier, who was recalling his past, repeats the lie as he wakes up).

Priest also made a point of subverting the original’s recurring inspirational line about how ‘one man in the right place at the right time can make a difference,’ but I won’t spoil it here… Suffice to say that when that line is finally uttered, near the end of issue #6, it’s in the least inspirational tone you can imagine!

Our Fighting Forces: House Call

Our Fighting Forces: House Call

I like Christopher Priest’s take on this material so much that I wouldn’t mind reading another handful of stories by him. In 2020, DC let him have another go at it in the special one-shot Our Fighting Forces: House Call, which had a shinier look – courtesy of artist Christopher Mooneyham and colorist Ivan Plascencia – but where Priest’s voice was as distinctively cool as ever (as you can see in the page above). Let’s hope that, more than a brief sequel, this one-shot turned out to be a pilot for his return!

After all, as the last couple of weeks have painfully demonstrated, the world isn’t going to run out of international conflicts any time soon… In other words, no, it’s not all over for the Unknown Soldier.