If you read the last posts, you know that this month I’ve been discussing cool spy comics.

Historically associated with imperial rivalry and pointless carnage in the public imagination, World War I doesn’t seem to have inspired nearly as many works in the spy genre as World War II or the Cold War. Nevertheless, there are some solid films (The Spy in Black) and novels (The First Casualty) worth checking out.

There are also some very good comic books…

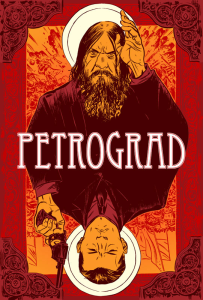

PETROGRAD

Set in its titular city during the snowy winter of 1916 and mixing fictional characters with historical figures and events, Philip Gelatt’s and Tyler Crook’s brilliant graphic novel Petrograd tells the story of the murder of Grigori Rasputin, the mystic advisor of the Romanovs, from the point of view of an exasperated British secret agent, Cleary, tasked with organizing the sordid affair.

The SIS are trying to keep the UK’s Russian allies in the war, since they suspect Rasputin has been advising the Tsarina to negotiate a separate peace with the German Kaiser (her cousin). The murky morality of this mission, coupled with the fact that from today’s vantage point we know how things turned out in Russia and in WWI, raises what could have been a merely enjoyable potboiler into an engrossing, thought-provoking read. Not only does Petrograd successfully combine elements of political thriller and period drama, it also features a touch of heartbreaking romance and deadpan humor (one running gag concerns the conspirators’ terrible plotting skills, with the aristocrats spending most of their time bickering about the symbolism of each gesture rather than considering the practical requirements).

There are three captivating characters at the heart of the book. With his sad eyes and mysterious Irish background, Cleary at first seems to be an outstanding agent, navigating through social classes, having befriended well-connected members of the aristocracy, of Bolshevik revolutionary cells, and of the Okhrana (the Tsar’s secret police). However, you gradually get the impression that what makes Cleary so adaptable may also be his greatest weakness, as he is harboring a deep-seated identity crisis. Then there is Grigori ‘Mad Monk’ Rasputin, who is such a legendary eccentric figure that he has popped up in many pulpy comics throughout the years, from The Shadow Strikes! to Firestorm, from Hellboy to the recent Rasputin series by Alex Grecian and Riley Rossmo. Finally, there is the cold city of Petrograd, who is arguably a character in its own right, evolving and constantly interacting with the rest of the cast.

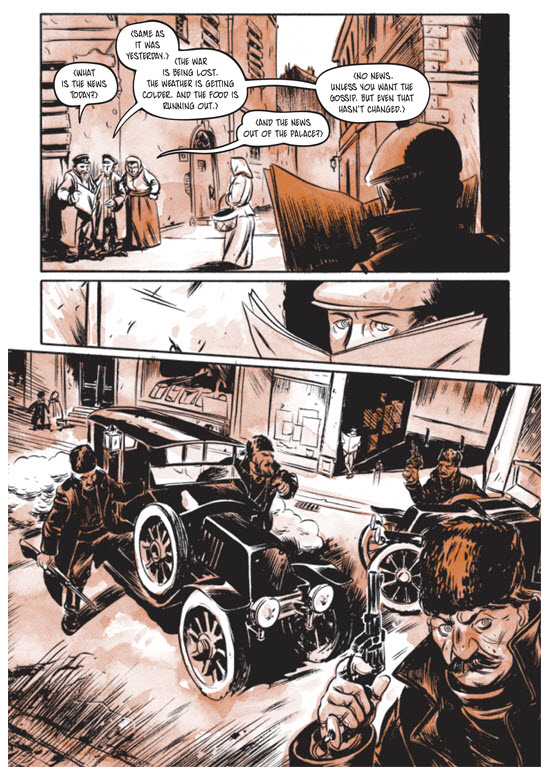

That said, all the characters have their moments, from subtle gestures, like removing a hat near the statue of the old tsar, to inspired dialogue exchanges. Cleary’s contact at the Okhrana tells him that he clings to his words but actions make him sick, to which he replies: ‘I am afraid you’re confused. It’s the vodka I cling to and the borscht that makes me sick.’ Later, during a lovely scene in the city’s outskirts, someone describes a gypsy camp as Petrograd’s own ‘land of outcast dreams,’ where ‘one day goes to die and the next comes to be born, a feast for senses starved by a day’s doldrums.’

Despite Philip Gelatt’s ear for witty dialogue, most of the storytelling is visual, especially during the tour-de-force sequence that is Rasputin’s assassination attempt, which goes on for over thirty intense pages. Fortunately, the art couldn’t be in better hands: Tyler Crook draws with all the expressiveness and dynamism of Will Eisner, staying true to the script’s realistic tone and deliberately measured pace while crafting a melancholic atmosphere, enhanced by the sepia colors. I particularly like Petrograd’s scene transitions as the book moves from one social milieu to the next. Like Gelatt, Crooke is able to imbue every character with a sense of humanity, treating them with compassion, knowing that they are part of something much larger than they can perceive.

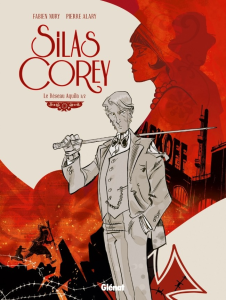

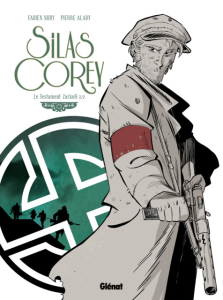

SILAS COREY

I will finish with something a bit different. The French comic series Silas Corey reimagines World War I and its aftermath through the adventures of the titular hero, a snobbish private detective with an opium habit and a skilled Vietnamese assistant. Told at a breakneck pace and with undisputable zest, this is a wonderful cloak and dagger romp that, criminally, remains unpublished in English.

The first couple of books take place during the spring of 1917. In this version of history, the pacifist Joseph Caillaux is still prime minister, so the opposition leader, Georges Clemenceau, hires our hero to search for a missing journalist who appears to have found incriminating evidence linking Caillaux to the Germans. This is only the starting point for a maze-like yarn bursting with double-crosses and misdirection, in which Silas Corey manages to also be hired by the French secret services and by the ominous arms dealer Madame Zarkoff before a powerful climax at the trenches. The second arc, set immediately after the armistice, sees Corey searching for Zarkoff’s son among the communist uprising of Bavaria, getting entangled in the chilling politics of post-war Germany.

With its WWI spies frantically running around, its sudden touches of humor, and its willingness to play fast and loose with history, Silas Corey sometimes nears the lunacy of Alfred Hitchcock’s Secret Agent and Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s A Very Long Engagement (without ever reaching either the all-out comedy of Blackadder Goes Forth or the all-out fantasy of the recent Wonder Woman flick). Nevertheless, the comic doesn’t shy away from its grim background. In fact, the protagonist is not a mere post-Holmesian caricature – underneath his cynical posture, Corey is haunted by memories of the front…

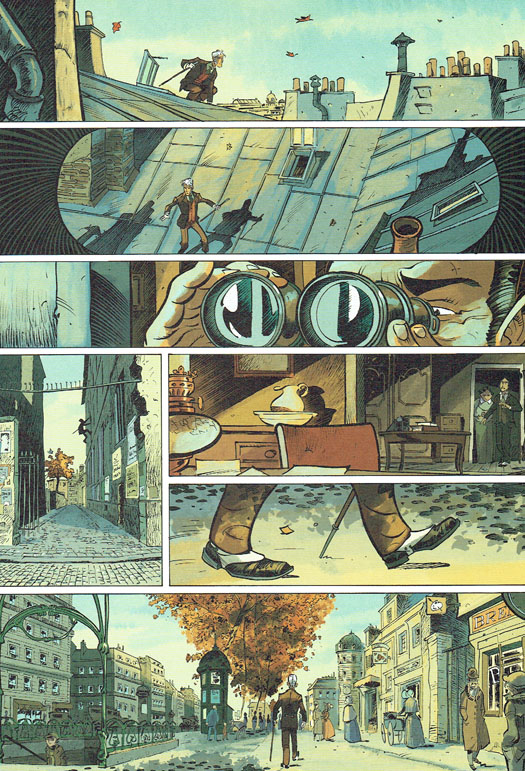

Pierre Alary’s art is cartoony yet vibrant, its POV constantly shifting from close-ups to wide angles. Alary fashions beautiful establishing shots and somber glances with the same panache as he delivers bloody fistfights, high-octane chases, and massive explosions. The colors are by Bruno Garcia, who gives each scene a distinctive tone, helping readers keep up as the stories quickly move from one setting to another.

As for writer Fabien Nury, suffice it to say that he is one of the strongest voices in French genre comics at the moment. He has a special flair for nifty period pieces, having written dozens of books inspired by various literary traditions. So far, my favorites are the hardboiled crime series Tyler Cross, set in the sixties, the darkly satirical The Death of Stalin, set in 1953, and the Kelly’s Heroes-esque graphic novel Comment Faire Fortune en Juin 40, set during the Second World War.

NEXT: Batman’s gadgets.