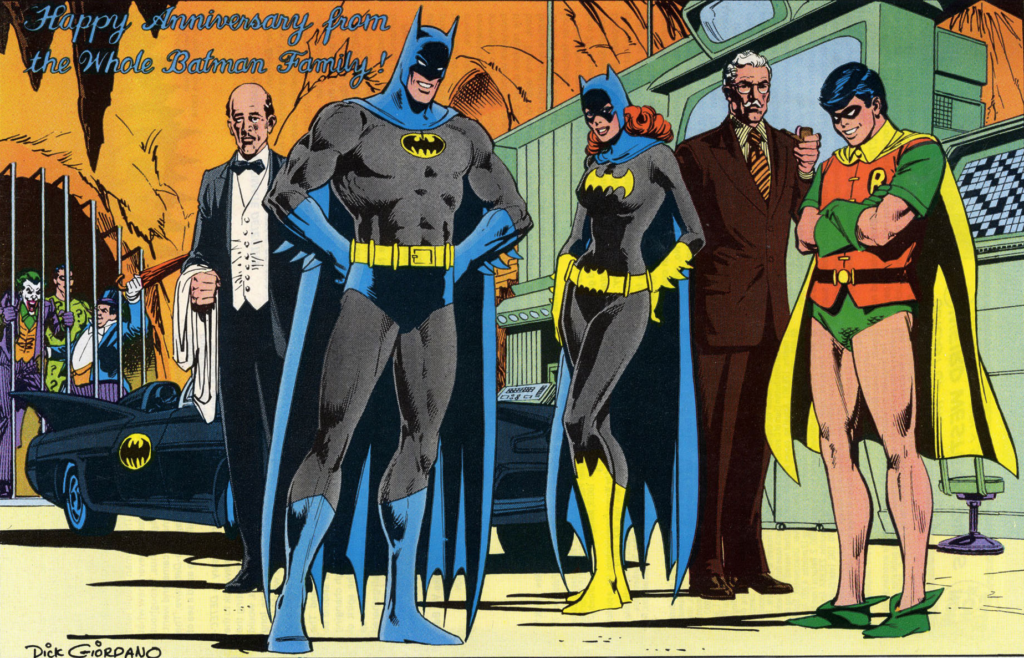

Detective Comics #483

I started this blog a decade ago in the spirit of entertainment – for others as much as for myself. I spent much of my life reading and thinking about Batman comics, so I wanted to share some of the most interesting or amusing things I’d found with those who had devoted their time to wiser pursuits.

On hindsight, I guess I also wanted a place to talk about these books because nobody around me cared to listen… I had fun overanalyzing them and recontextualizing them. Occasionally, I gently mocked them or complained about certain creative choices, but the general spirit was one of celebration – I sought to reflect about why I enjoyed these works in the first place and to explain how they could be appreciated in spite of their flaws or even because of them (after all, the most problematic aspects could actually make them more fascinating, in some way).

As it turned out, my main audience were not the uninitiated, as I had expected, but fans (and even a couple of pros) who were also into Batman and already eager to engage with his stories. Or, at least, those were the ones who posted comments and got in touch with me through the blog’s email (which I always appreciated, even though I often failed to reply).

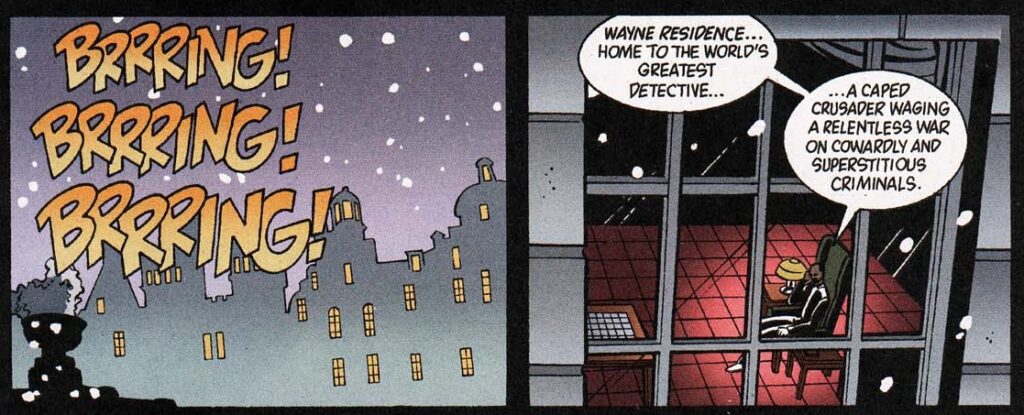

Gotham Knights #39

As time went on, Gotham Calling became more and more a means of escape – a corner of my crowded world where I could write freely, sometimes almost thoughtlessly, for an audience of unknowns, about things that were far from my job, from my love and family life, from all kinds of everyday struggles as well as from larger political and existential questions (although, of course, these would inevitably linger in the background). As it became a compartment to store my thoughts and feelings on my lonelier leisure activities, the blog actually grew more expansive, going more and more into non-Batman comics, films, and picture-less novels.

In part, this was a reflection of the fact that I was growing disenchanted with the current direction of Batman comics, so when I wrote about those I mostly looked at previous works that I remembered or reread. Much of the stuff I was drawn to at the time (including older comics) wasn’t related to the Dark Knight – and that was the stuff I felt the urge to share and discuss. Gotham Calling became a site for exploring various storytelling traditions that appealed to me, which I realized could be relatively eclectic and therefore, after five years, I broke down the blog into genre-oriented categories – so that even readers who were not into, say, crime yarns or international intrigue knew where they could find posts about superheroes or other types of fantasy…

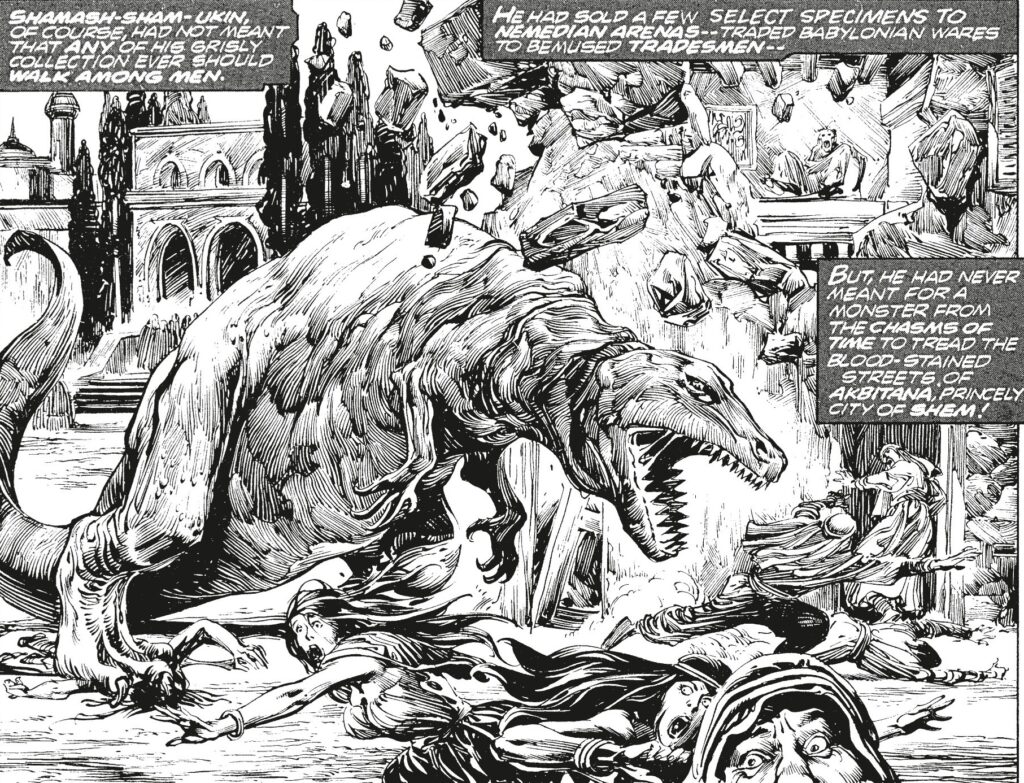

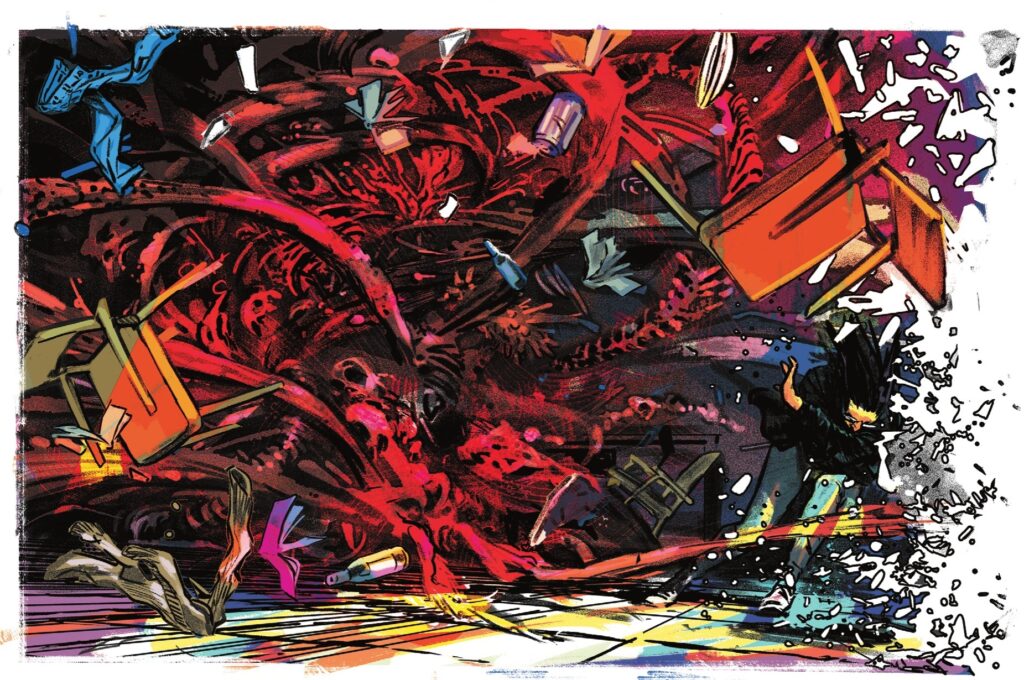

The Savage Sword of Conan #7

Five years later, things have continued to change. I’ve somehow managed to incorporate many of these objects and concerns into my professional life, which is satisfying for me although harmful for the blog – since I blog to escape, I don’t always feel like blogging about something I’m writing about for work anyway. Still, Gotham Calling has remained a testing ground for ideas, a pretext to delve into peripheral material, and a cathartic forum where I can express myself impulsively and creatively, without the formal rules (and careful rigor) of academia.

The thing is that, because my professional work has tended to focus on audiovisual history, films (and, to a lesser extent, TV and streaming) have come to occupy more and more of my time and thoughts… and, consequently, to occupy a sizeable part of this blog. It has gotten to a point that I’ve decided to actually change Gotham Calling’s tagline/mission statement to encompass both comics *and* cinema, the two visual media that have profoundly shaped my brain.

Not that they will have equal representation, necessarily… For one thing, I intend to continue posting weekly reminders that comics can be awesome every Monday. More structurally, I doubt I’ll do more than a couple of film-related posts per month, since – like I said – I already research and write enough about cinema for work, so this is just a gateway to vent informal, unpolished considerations and to recommend curious stuff I’ve come across. By contrast, whenever I have free time, I often spend it reading, thinking, and writing about comics, so there’s bound to be an endless supply of material (as long as the rest of my life doesn’t get in the way). I’m constantly fascinated by this medium’s history and potential to visually communicate not only narrative, but also intense mood and abstract ideas.

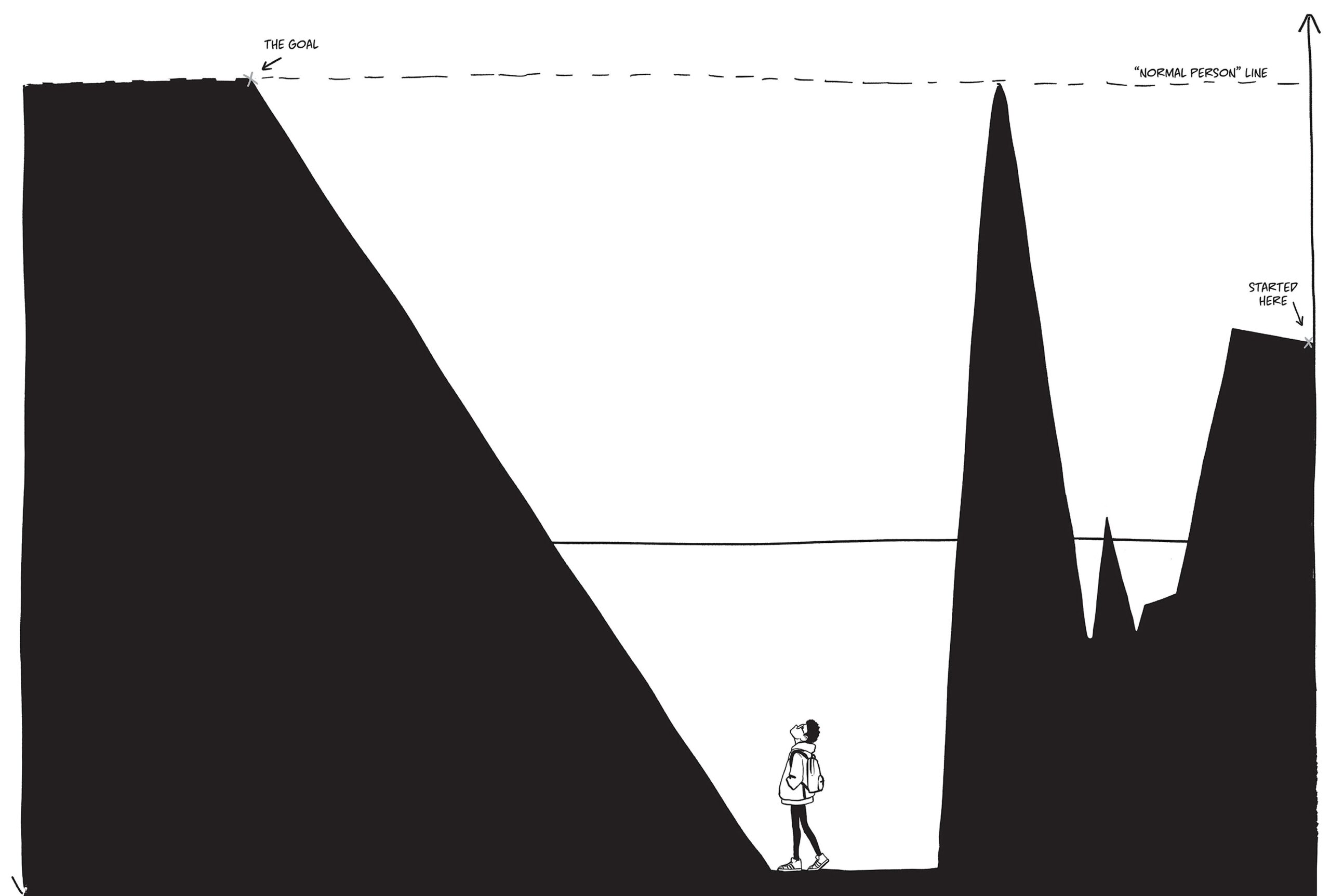

Shubeik Lubeik

Since Gotham Calling is no longer a blog just about the Batman franchise, or even just about comics, then what kind of unifying focus can readers expect? Well, the honest answer is that the running thread is my own personal sensibility, but I realize that is not particularly helpful… After all, I am now ten years older than when I started the blog and, let’s face it, my tastes and interests have evolved, even if I continue to have a passion for genre fiction and for what used to be considered the nerdier side of pop culture (which has become much more mainstream in the past two decades), especially older stuff from throughout the 20th century.

I like fun tales, but my idea of ‘fun’ can be quite broad, ranging from middlebrow fiction to ultra-trashy exploitation. Every once in a while, a book comes along that redefines my understanding of what a genre yarn can be (how it can look like, how it can approach storytelling from different angles) and I may spotlight it as Gotham Calling’s Book of the Year, although I’m more often drawn to run-of-the-mill products, showing how far you can go and what you can pull off even if you color inside the lines.

While it helps if the creators’ enthusiasm shines through, I’m not too big on analyzing intent… I suspect many of my favorite creators are probably assholes in their personal lives (indeed, some have been outed publicly). In any case, I find it more stimulating to think about the ways in which works can be read *regardless* of the intended message.

That said, I think I can single out four motifs that tend to determine most of the stories I consume, enjoy, and wish to write about.

The Nice House on the Lake #11

The first one is violence. Although I don’t dig all depictions of violence, per se, most of the works I dig do tend to have violent elements, whether physical (action, killings, gore) or psychological (abusive language, broken taboos, disturbing dilemmas), from revenge thrillers to body horror.

I’m not a violent person and, in fact, I’m generally afraid of violence in real life, but it’s something that often appeals to me in fiction – perhaps as a compensation mechanism (I get to vicariously experience it without actual danger or consequences), perhaps as a catharsis (the liberating fantasy of mayhem and destruction for someone stuck in an ordered, if stressful, life), or perhaps just as a purely aesthetic experience (films and comics are ideal vehicles for sound and fury).

The energy of explosions, the choreography of fights, the dynamism of aggression… These are just so damn cool and visual and, well, cinematic. It’s not all that cinema can give, but the potential is there to thrill our senses, to give us a rush, to push our buttons at the most primeval level.

I also find it pretty funny.

Damn Them All #8

Shock, fear, and disgust are like spices prickling the tongue and making it feel alive, their lack of subtleness providing easy and instant gratification when I’m in a lazier, less sensitive mood (which isn’t always the case, but it’s usually the case with the sort of material that brings me to this blog).

Sure, violence itself can serve different purposes (whether in the stories or outside them) and have multiple types of impact. It can feel anarchic and revolutionary, but also fascistic, oppressive, and like a scary expression of toxic masculinity. So, laughing at violence can be a way to reinforce distance – to ridicule it and feed my contempt. Yet laughter can just as well be a more instinctive, joyful response to slapstick, since most of the violence that delights me does look blatantly silly. Hell, I’ve posted over 250 images of a guy dressed like a bat kicking (and kneeing) people (and monsters) in the head. Fun!

In any case, you can see why Gotham Calling keeps gravitating towards war, crime, superheroes, and westerns…

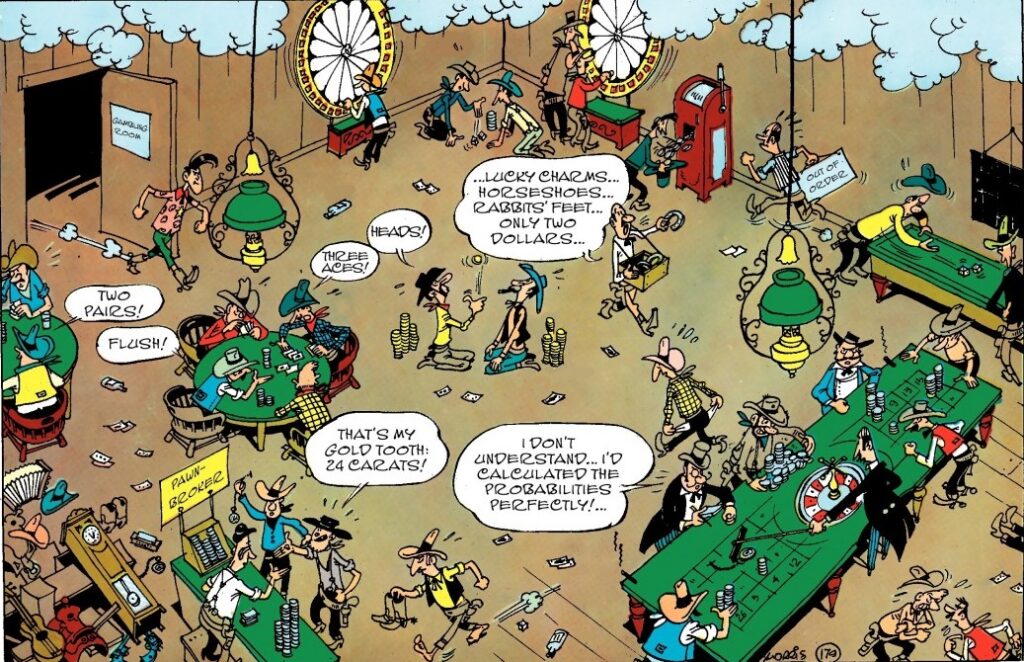

Lucky Luke versus Pat Poker

The other reason is that these are all genres that tie fairly neatly with my interest in history – by which I mean not just an interest in the past, but also in the various ways we imagine the past, from Garth Ennis’ attempts at realism in his comics about World War II all the way to Lucky Luke’s proudly absurdist caricature of the Old West. Since our translation of the past is always distorted to some degree (like all translations, by definition), I enjoy period pieces’ flagrant balancing act between such inevitable distortion and a more or less clever use of the raw material of history (or, at least, of the recognizable perceptions of history consolidated over time).

It doesn’t mean inaccuracies or anachronisms can’t be annoying, sometimes messing with my nitpicky impulses, but they’re ultimately part of the game – the game being to compare all these translations of the past and to keep envisioning history with new eyes. And so, as much as I can be moved and intrigued by accounts that make me reconsider how people used to live, I also love pulpy historical adventures that play fast and loose in the name of entertainment, approaching bygone eras as just another exotic setting to jazz up formulaic yarns while compensating for low production values with shameless verve, visual imagination, and a frantic pace, from the cardboard palace intrigue of Serpent of the Nile to the rollicking action of something like Zatoichi and the Chest of Gold or If You Meet Sartana… Pray for Your Death (or any episode of Xena: Warrior Princess, for that matter). They’re not ‘realistic,’ nor do they claim to be, but I don’t require full ‘realism’ from tales set in the present either, just enough coherence to anchor their version of ‘reality.’

And it’s not just narratives explicitly *about* the past that appeal to my historian tendencies… Ultimately, stories tend to channel the time of their own making, so they can all be historicized. Whether we’re talking about books and films made in the present or decades ago, I dig trying to discern what comes down to the creators’ own eccentricities and how much of it can actually be attributed to a wider zeitgeist. This is what typically draws me to older works: not some reactionary they-don’t-make-them-like-they-used-to mindset, but rather an appreciation for the extra layers those works acquire when looked at in hindsight. For instance, I suppose there are only so many cult thrillers from the early 1970s you can watch (Duel, Westworld, Deliverance…) before you spot a clear pattern of deconstructing male performativity and exposing masculinist fantasies as utterly disturbing, which you can then begin to explain by considering the rise of women’s rights movements in that era and how this must have informed new ways of looking at gender.

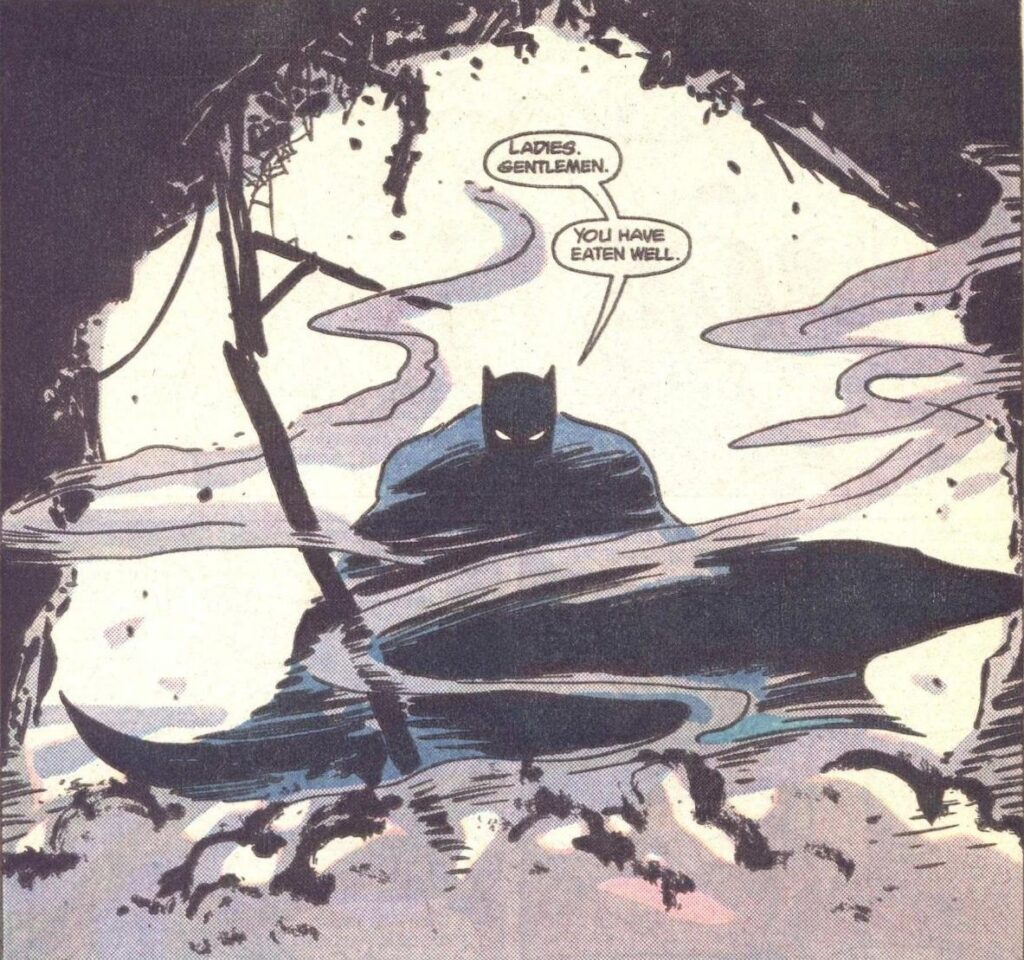

Batman #405 (1987)

Batman #652 (2006)

Batman/Superman: World’s Finest #28 (2024)

Similarly, I enjoy considering how texts fit in – and often engage with – the history of their own media. The fact that superhero comics and blockbuster movies have become so inward-looking and obsessed with revisiting or reworking what came before means they often come across like repetitive, predictable, creatively bankrupt fan-pandering, as mega-corporations eagerly mine their IPs for all their worth while cynically exploiting easy nostalgia and brand recognition, but I can’t wholly avoid the occasional pleasure in unpacking all this wide, rich tapestry of interlocked characters, narrative threads, and visual echoes (like the one above) across the decades – and the baggage I bring to each story as a reader. For better or worse, my head is chockful of geeky knowledge, particularly regarding the DCU, as if I’ve spent my whole life in preparation to be able to pick up every single allusion, cameo, gag, and revelation in the latest iteration of World’s Finest… so it feels kind of rewarding to sense decades of study paying off.

Beyond the encyclopedic mastery of the lore of specific sagas and universes, there is a more general satisfaction that comes from putting together the intertextual pieces of the larger puzzle, uncovering paths and links that connect different works: to spend years wondering about whether it was Len Wein’s Swamp Thing or Gerry Conway’s Man-Thing that first came up with the science-gone-wrong-in-the-swamp premise, only to realize they were both probably riffing on Al Feldstein’s ‘The Thing in the Swamp!’ (from way back in Haunt of Fear #15); or to identify the brief bathroom brawl in 2006’s Casino Royale as so instantly iconic that it served as blueprint for awesome expanded set pieces in both Mission: Impossible – Fallout and, more recently, Monkey Man. And this sort of communication can also happen across media: reading Joseph Conrad’s Under Western Eyes this summer, I couldn’t help wondering to what extent it inspired the graphic novels Petrograd and Death to the Tsar, to name a couple of great books operating outside of the business logic of soulless franchises.

Whether I giddily map out what ties scattered cultural works together or tiringly roll my eyes at another ham-fisted callback may come down to my mood as much as to the spirit and skill of the works themselves. The thing is that, by now, many professional creators tend to also be geeks who are clearly into all of this stuff and who search for complicity with the audience, although some are more subtle about it while others wear it on their sleeve, like when Will Pfeifer and David López built of couple of Catwoman arcs around dozens of film references…

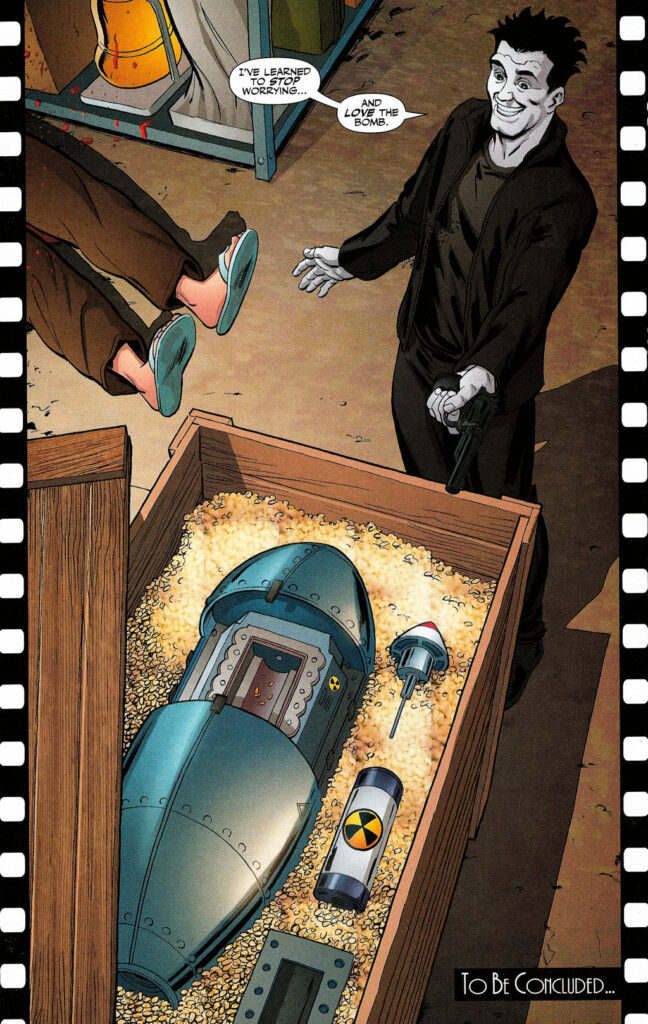

Catwoman (v2) #60

Tracing a line from these kooky comics to Kubrick’s satiric masterpiece can offer more than the mere validation of previously consumed pop culture. At their best, the niftiest works don’t just acknowledge each other but ingeniously build on a vast repository of shared references, prompting us to reconsider – and not just recognize – what we’ve seen before while providing fresh – rather than reheated – experiences.

Spotting connections can be particularly gratifying not only when it comes to metafictional tales that consciously reflect about the lineage of their genre or medium, but also when it comes to comedy, whose contrasts work better in context… In the case of Dr. Strangelove, a lot of the humor comes not so much out of the jokes themselves but out of the choice to shoot the film in a similar way to the kind of tense, self-important Cold War political thrillers of the time (including the brilliant trio Advise & Consent, Seven Days in May, and Fail Safe, not to mention the following year’s The Bedford Incident). Likewise, a big part of what made Airplane and Police Squad so hilarious was the fact that they starred character actors such as Peter Graves, Leslie Nielsen, and George Kennedy, whom audiences had seen playing a straight version of the spoofed situations about a million times in the previous decades (especially since they did it in such a deadpan way, delivering the lines in the same tone as before, without ever acknowledging their silliness).

52 #24

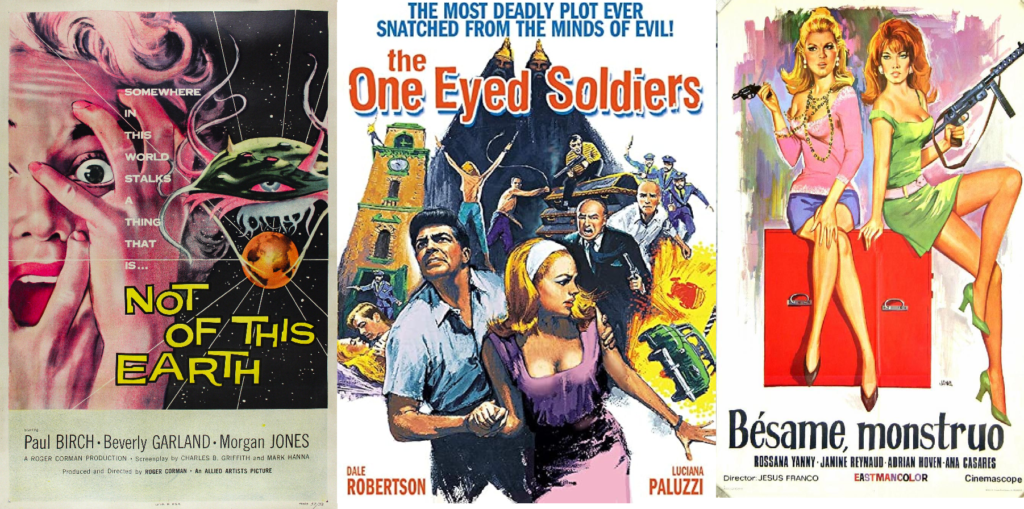

As much as I complain about the endlessly self-referential pop-eats-itself brand of postmodernism, I find something fresh and irreverent in the way some authors blow up iconic archetypes, formulas, and imagery, putting an idiosyncratic spin on them. I’m thinking of figures like trashmeister Jess Franco, who spliced pop culture with his own kitsch sensibility in Two Undercover Angels and Kiss Me Monster, a couple of utterly bizarre Spanish swinging sixties’ comedies with a hallucinatory web stringing together private detectives, masked thieves, secret agents, decadent dark magic cults, erotic dance numbers, a mad scientist, and a werewolf serial killer…

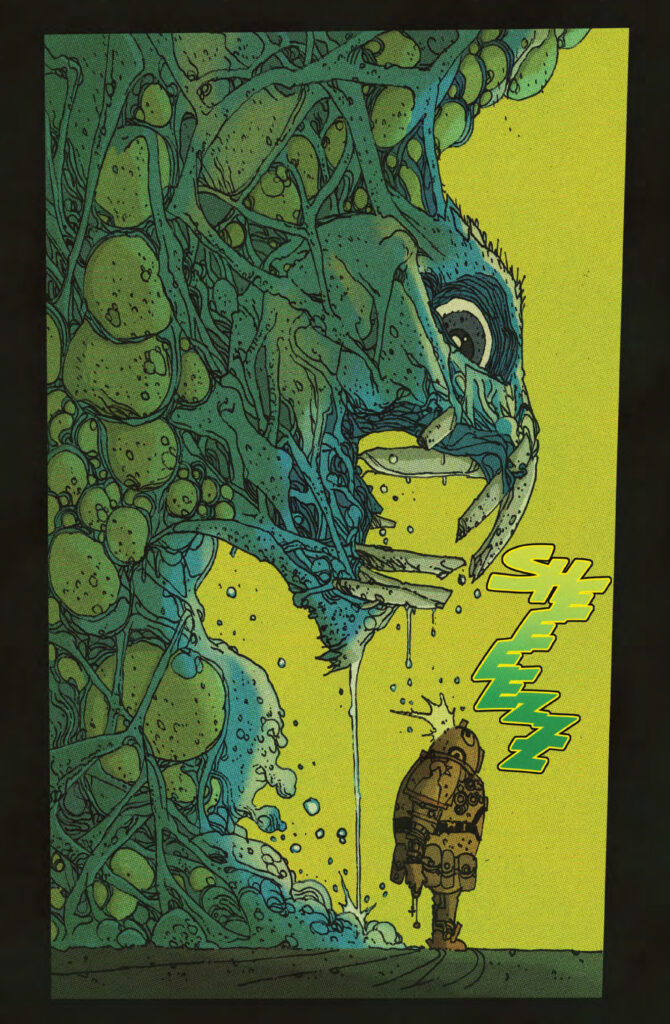

Which brings me to the third motif that recurrently pops up in the objects of Gotham Calling: surrealism. From Brendan McCarthy to Erica Henderson, I love it when artists cut loose and wildly express their kinks and visions unbound by a commitment to realism, even if I prefer it when there’s still a shred of recognition to hold on to, without going into full-blown abstract dream logic. In fact, it’s the mix that gets me – the offbeat combination of strangeness and familiarity can make a story creepy, funny, surprising, and, often, memorable.

Vanguard Illustrated #1

I’m not too much into drugs, so I look for trippy kicks somewhere else, onscreen and on the page. This even goes for works that weren’t necessarily meant to be odd but nevertheless came out that way due to their makers’ carefree attitude, whether as a result of an effervescent mind, like Jack Kirby’s eccentric cosmic operas, or just as a byproduct of stressed-out hacks throwing shit at the wall, like in several B-movies and Silver Age comics.

I suppose the allure is as much about the visceral ecstasy of losing one’s footing as it is about the cerebral challenge of understanding and adapting to new rules operating the world, embracing the very prospect of thinking and feeling differently… And if all this sounds quite vague, it is because, again, my fondness of surrealism spreads wide: it encompasses intelligent journeys into weirdness by creators who deliberately set out to expand our imagination and to disturb us out of our comfort zone, like the best works of Peter Milligan and Yorgos Lanthimos, but also to less pretentious fare, like the punk antics of Repo Man, the blaxploitation grindhouse horror of Sugar Hill, or the psychedelic sci-fi fantasy of 2000 AD.

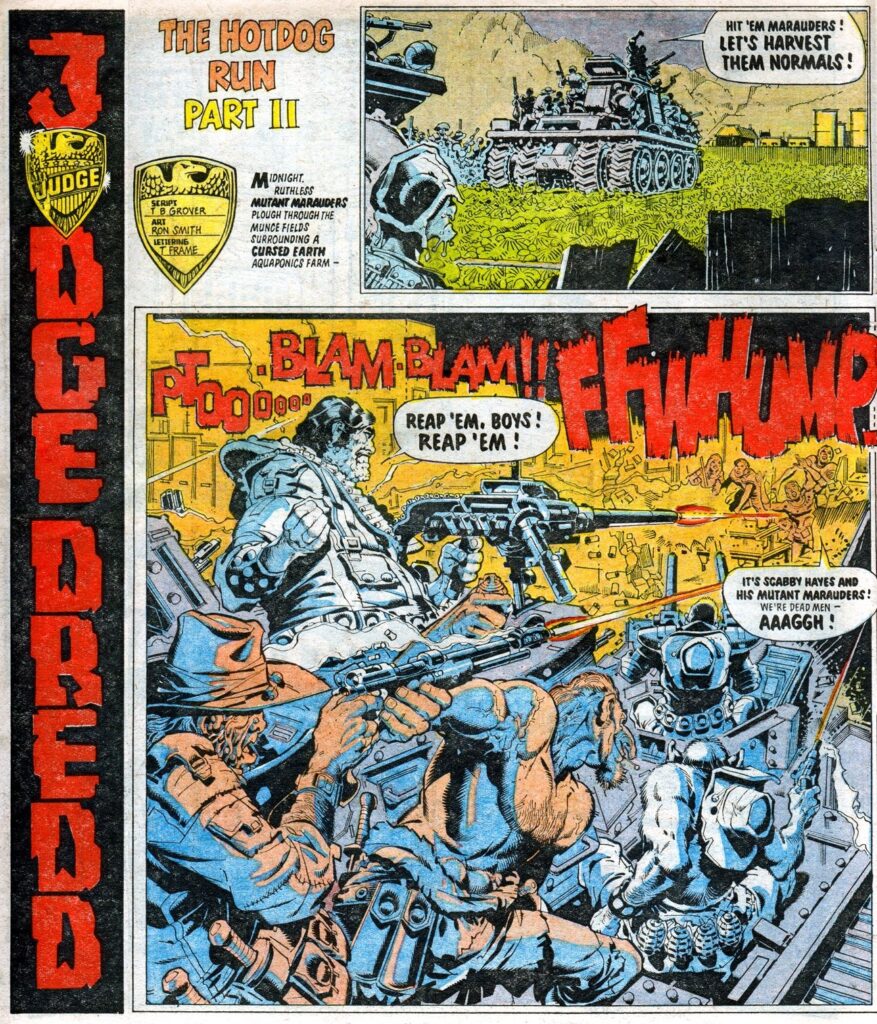

The latter magazine was the springboard for many of the writers and artists that keep reappearing in this blog, not least because several of them migrated from Mega-City One to Gotham City. Despite their markedly different editorial style, I’m quite the fan of both British and American comics, which I partly attribute to their surreal edge… While Batman and Judge Dredd can be fun characters by themselves, the major selling point for me has always been the mad cities they inhabit – they are very weird crimefighters in a cartoony world where crime itself is very, very weird.

2000AD #234

And then there’s politics. From Quino’s Mafalda and the punk-rock bands of my youth all through a lifetime of activism and academia, my brain is wired to think about the systems (in terms of both institutions and ideas) that organize much of our lives. As far as I’m concerned, power, strategic thinking, and/or clashes of ethical values are perfect ingredients for dramatically charged *and* thought-provoking narratives.

Like with historical fiction, I’m a sucker for political thrillers not so much because of what they show about the world, but because of what they show about how we view the world. They can offer original takes, or efficiently manipulate the way an issue is framed so as to push me in uncomfortable directions, or reassuringly nail perspectives that I already believe in, or come up with something bafflingly outrageous… It can be a well-reasoned polemic, but it’s even better when there’s a stark contrast between the serious weight of the subject matter and the lowbrow goofiness of the material, like in Iron Man’s comics about the Vietnam War or in Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman 1984, which turned Maxwell Lord into Donald Trump (thus treating Lord even worse than Greg Rucka did!). I don’t have to agree with their discourse and, sometimes, I don’t even have to like the works themselves in order to have a great time engaging with what they’re saying. It’s a subject that speaks to me and which I love speaking about, so it’s one that will surely keep coming back to Gotham Calling.

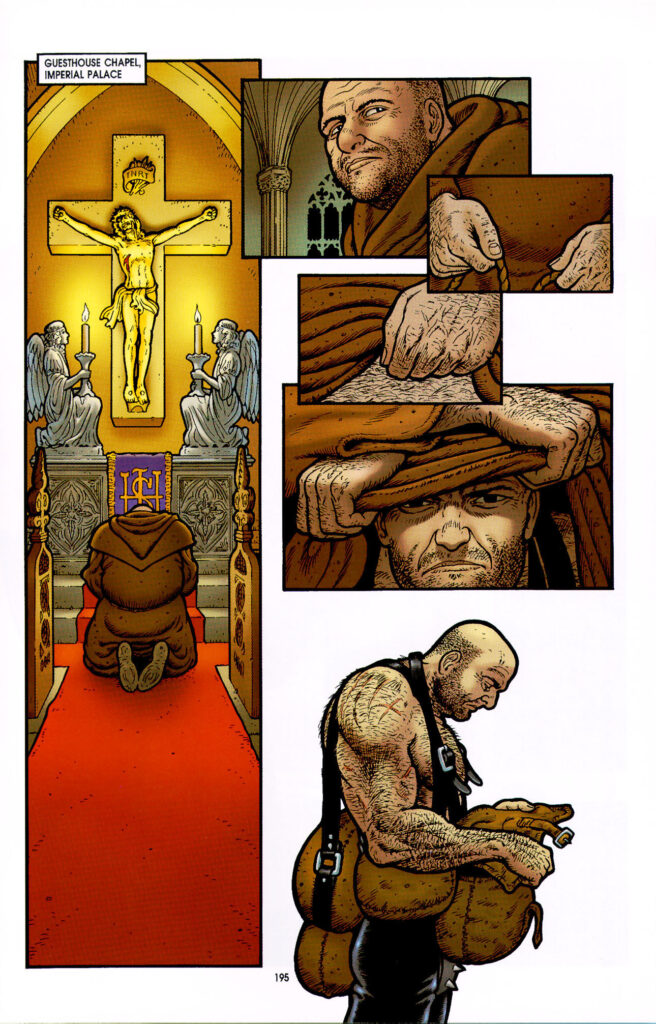

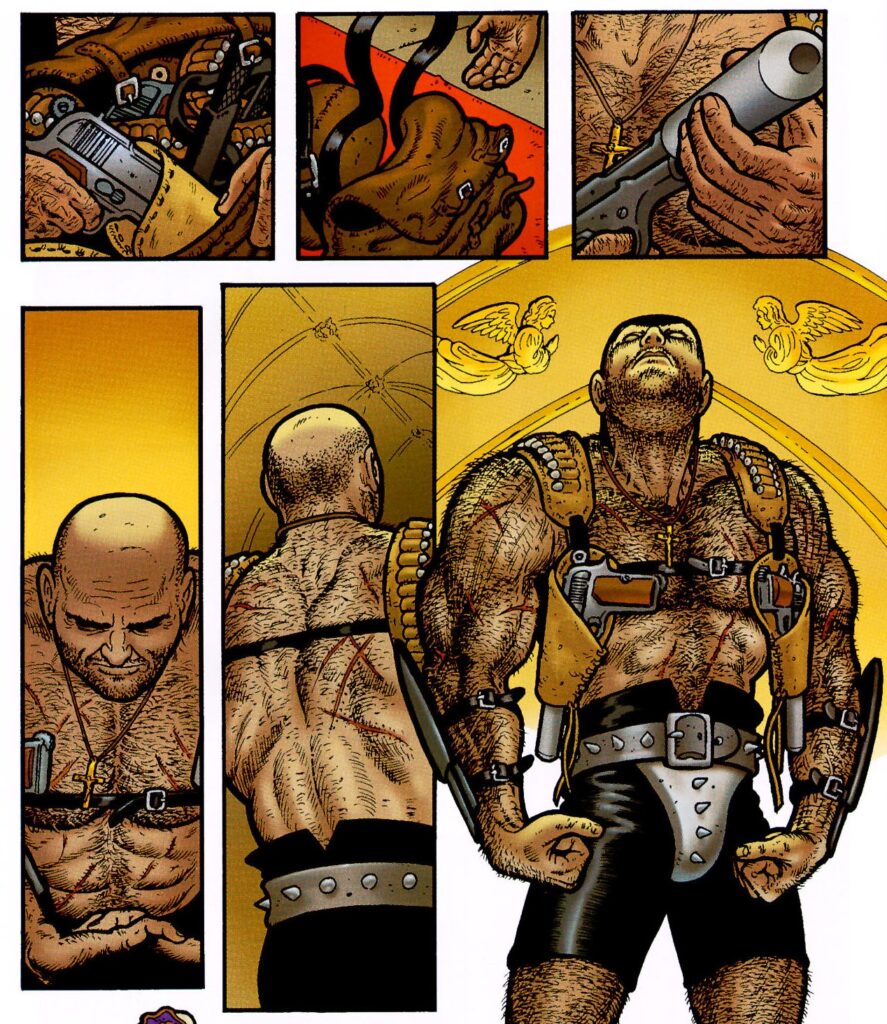

Heart of Empire: The Legacy of Luther Arkwright #6

The politics don’t even have to be explicit. I also delight in digging through layers of subtext, identifying the hidden assumptions, paradoxes, and less obvious implications of the worldviews that inform of each story. Take Ozark, a gripping show that for the most part preyed on fears of Mexican drug dealers and MAGA-looking rednecks and white trash, but which ended up critically indicting its liberal protagonists and their family values. Breaking such products apart and scrutinizing their nuts and bolts may seem like a way to suck out their enjoyment, but it also serves to find new ways of enjoying them. So, the hyperlinks in the blog are just as likely to lead you to a rock song as to a discussion of the politics of corporate characters or the underlying philosophy of a post-apocalyptic franchise.

Not that every monster has to be a coherent metaphor or part of a complex allegory to elevate my interest in a book or film… I’m not looking to raise the symbolic capital of schlock – it’s just that interpreting what lies underneath the surface can often be as amusing as switching off all common sense and just letting the lizard brain take over (which I also like to do, but it’s less likely to lead to a blog post).

Don’t Spit in the Wind #2

And so, finally, a word on schlock.

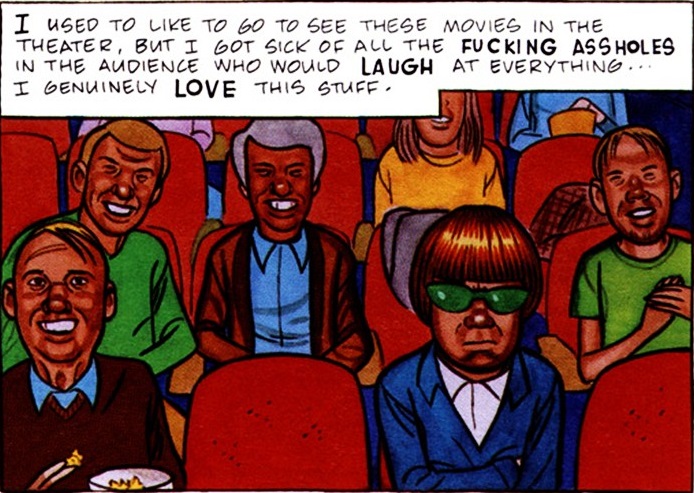

Just as some elitists avoid and sneer at tasteless, unsophisticated works, hipsters have a blast ironically hate-watching or condescendingly laughing at the incompetence and low production values of what they call so-bad-it’s-good movies and books. In general, these are not the guiding attitudes of Gotham Calling. I don’t necessarily like all that is schlocky per se and I can certainly be as smug and scoffing as anyone else, but when I mention schlockiness in this blog it tends to be an appreciative term.

I know I’m not alone in discerning a certain endearing charm in ultra-cheap products that know their limitations but unapologetically invite you to play along. At their best, these can be pretty inventive and entertaining on their own intended level, whether it’s a moody chiller about an alien vampire or a bonkers treasure-hunting adventure shot in a few days in former Yugoslavia…

When I watch a movie like 1967’s Battle Beneath the Earth, where the US Navy realize a Chinese army has dug a whole complex of tunnels under the United Sates and is about to attack, I know the film is silly, cheesy, and shoddy-looking (not to mention militaristic, racist, etc), but merely mocking its obvious flaws feels so much less gratifying than appreciating what it can offer (a mind-bending adventure whose unique logic creates an exciting scenario in an original setting, including eerie sequences, like when the heroes try to lower the whole country’s noise levels so that they can listen better) or thinking about its possible meanings (the way the picture visualizes Cold War hysteria and paranoia… or the way British filmmakers mimic Hollywood schlock from the previous decade).

To quote a classic: ‘I genuinely love this stuff.’

Eightball #16