It turns out the most satisfying way to appreciate Todd Phillips’ Joker was to almost forget that it was a Joker movie.

Taken as a DCU entry, the project didn’t particularly appeal to me: a Joker origin story (when the character has always worked best as an enigmatic wild card who is more force of nature than relatable person) taking the Clown Prince of Crime seriously (rather than embracing his caustic wackiness) and apparently removing Batman from the proceedings (even though the Joker is much more interesting as an opponent to the hero).

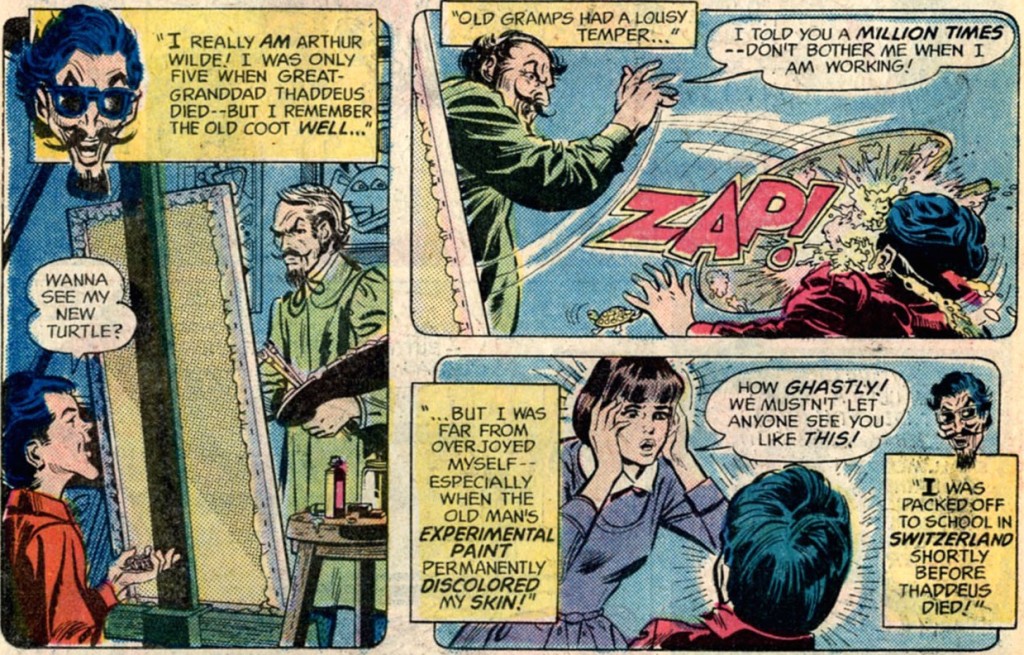

Still, at least I knew Phillipps’ origin wasn’t going to be as lame as this one:

The Joker #5

The Joker #5

In the past, I’ve enjoyed tales told from the Joker’s point of view (Robin #85, a couple of issues of the 1970s’ short-lived The Joker comic, The Brave and the Bold’s ‘Joker: The Vile and the Villainous!’ episode), but they’ve tended to exploit the amusing absurdity of the character’s surreal perspective rather than humanize him in a deliberately depressing way. And while I admit there is much to like in Alan Moore’s and Brian Bolland’s The Killing Joke (even if not all of it has aged well), I still haven’t gotten over the sour taste of Brian Azzarello’s and Lee Bermejo’s Joker graphic novel – by far one of the most atrocious works ever published by DC – so the thought of a grim, stripped-down approach to the Harlequin of Hate didn’t stir up pleasant memories.

Then again, I do love Elseworld tales, where I am much more forgiving of revisionist twists that would’ve upset me if they were canonical retcons. Making the Waynes’ murder a product of class warfare (implicitly recasting the Dark Knight as a reactionary retaliation from the 1%) and linking the Joker’s and Batman’s origins (both more *and* less directly than in Tim Burton’s blockbuster) aren’t completely new approaches, but they are elegantly pulled off – at least the latter, with both characters simultaneously realizing who they will be for the rest of their lives, thus retroactively (if subtly, offscreen) presenting the Joker as Batman’s primal counterpart.

In any case, it has long been established – and the epilogue toys with this – that, when it comes to the Joker, origins and recollections aren’t meant to be accepted at face value… As Moore famously had him declare: ‘If I’m going to have a past, I prefer it to be multiple choice!’

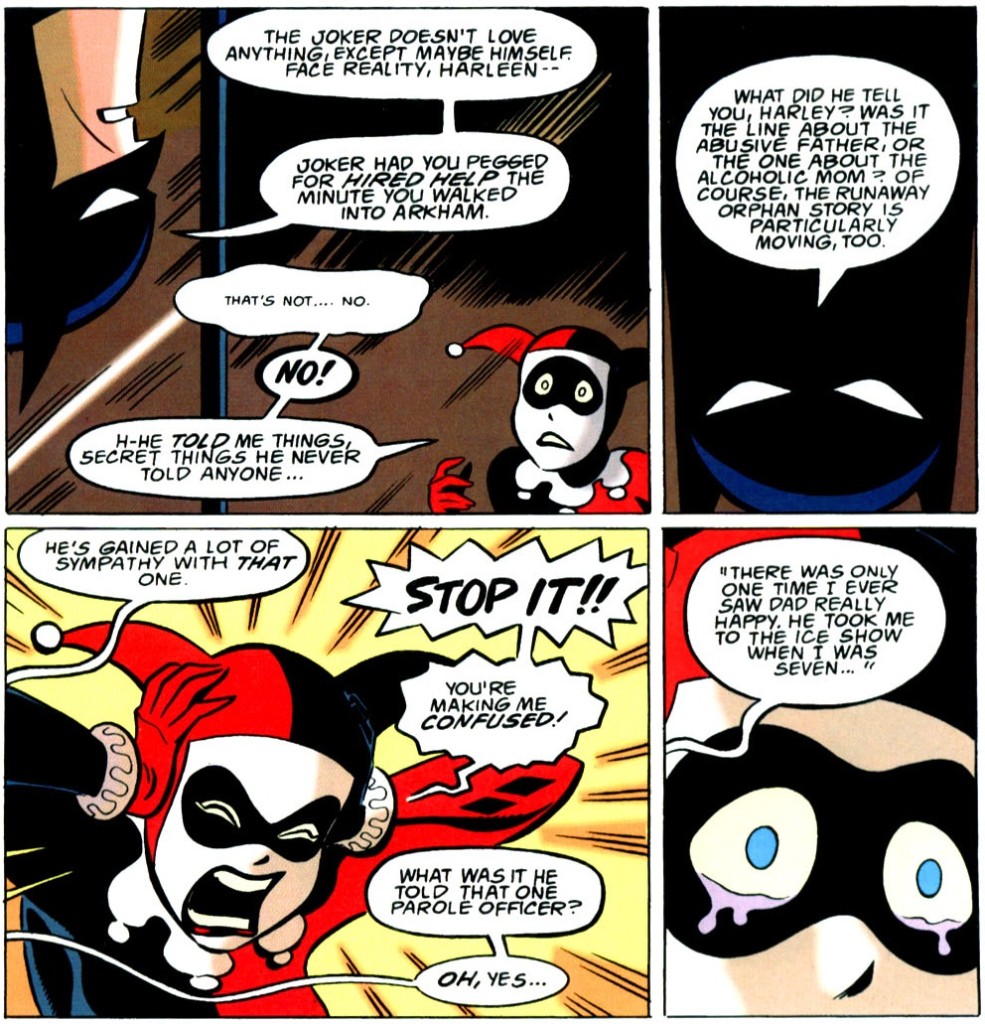

Mad Love

Mad Love

More rewarding that looking at Todd Phillips’ movie as yet another attempt to ground Batman’s cartoonier elements in sullen, self-serious pseudo-realism is to look at it from the opposite direction, approaching Joker as a quirky Joaquin Phoenix-vehicle that uses a goofy comic book character – just like it blatantly riffs on Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver and King of Comedy – to spin a tragicomic arthouse drama about mental illness. Since most of Joker can ultimately be interpreted as a sick joke the titular character came up with (along the lines of ‘What if things had actually happened like this?’), you can go further and see it as the fantasy of a real-world patient, called Arthur Fleck, who is weaving into his memories bits from old movies and comics he came across over the years.

That said, it’s pointless to ignore the genre dimension intrinsic to any story starring a member of the Caped Crusader’s rogues’ gallery. Between the encroaching mood, the sudden bursts of violence, and the disturbing imagery (those blood stains on the white makeup…), Joker is – on top of everything else and true to the source material – a seriously mean slice of psychological horror with sprinkles of dark humor.

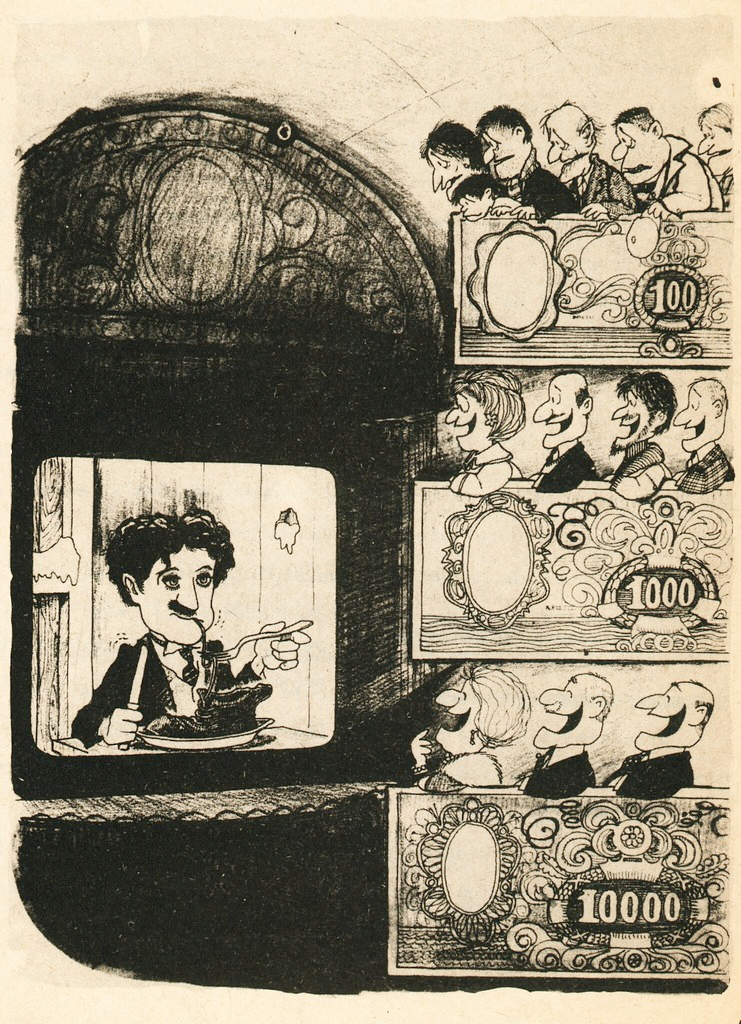

Moreover, even setting aside what I believe are pretty misguided controversies over the film’s discourse on terrorism, it sure is tempting to uncover in it a statement that goes beyond Gotham City, whether it’s a topical contribution to debates over the links between ‘lone wolf’ massacres and insufficient state provision of mental health care or just a populist indictment of social inequality (although, let’s face it, if you want to see an imaginative parable about class struggle on the big screen this year, you’ll be better served with Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite). Ambiguously playing into the ongoing culture wars, Joker suggests that comedy can be (literally) violent and its enjoyment conditioned by your position in the world. At one point, Phillips even doubles the ‘sad clown’ trope, as he slightly echoes a Quino cartoon involving Chaplin’s Little Tramp:

Yet I think reducing the film to such readings does it a disservice. Joker is at its most powerful when taken as a genuine character study, conveying the interiority of a damaged man falling apart (or, from another perspective, coming together) as he tries to simultaneously cope with a mental disorder and with everyday life’s micro- and macroaggressions, from wider social pressures to personal family drama. The protagonist himself explicitly tells his audience that he doesn’t want to be a political symbol, he wants to be treated as a human being with specific issues. Indeed, the film doesn’t justify the Joker’s actions so much as conceive a (physical and psychological) context in which they could emerge. The fact that we somehow empathize with this messed up protagonist is the greatest accomplishment of Todd Phillips’ atmospheric direction, which makes the most out of Lawrence Sher’s beautifully melancholic cinematography and plenty of effective needle drops along the way.

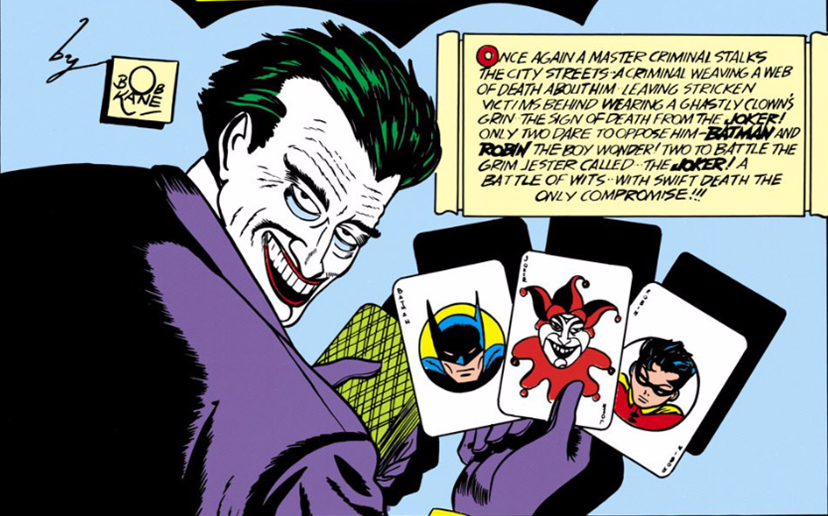

Above all, what unquestionably elevates the whole thing is Joaquin Phoenix’s nuanced, compelling performance, which, for long stretches of the film, invites you to abandon any preconceptions and just accept Arthur Fleck’s subjectivity. If part of the fun is watching Batman’s mythos turned upside down, the most enjoyable moments actually take place when you let yourself forget Joker is set in the DCU at all. Phoenix’s gentle dancing, his unsettling gaze, his unexpected mood swings, his uncontrollable laughter, his facial plasticity, and his bony, contorted body make the character more concrete than a mere metaphor for urban malaise or rampant capitalism – and surely more unique than the embodiment of a multi-media franchise harkening back to a design Bill Finger, Jerry Robinson, and Bob Kane created almost eighty years ago.

Batman #1

Batman #1

What won me over was not just finding at Joker‘s core a surprisingly rich and touching character-driven piece, but also the experience of navigating the tension between all the abovementioned layers, at times responding to the more dramatic aspects, other times to the geekier thrills of intertextuality, clearly not always in sync with the rest of the room. Like Arthur Fleck sitting in the audience at the comedy club, trying to make sense of what he’s seeing, I laughed when everyone was quiet and did so with a laughter that often betrayed discomfort, but I definitely got a kick out of it.