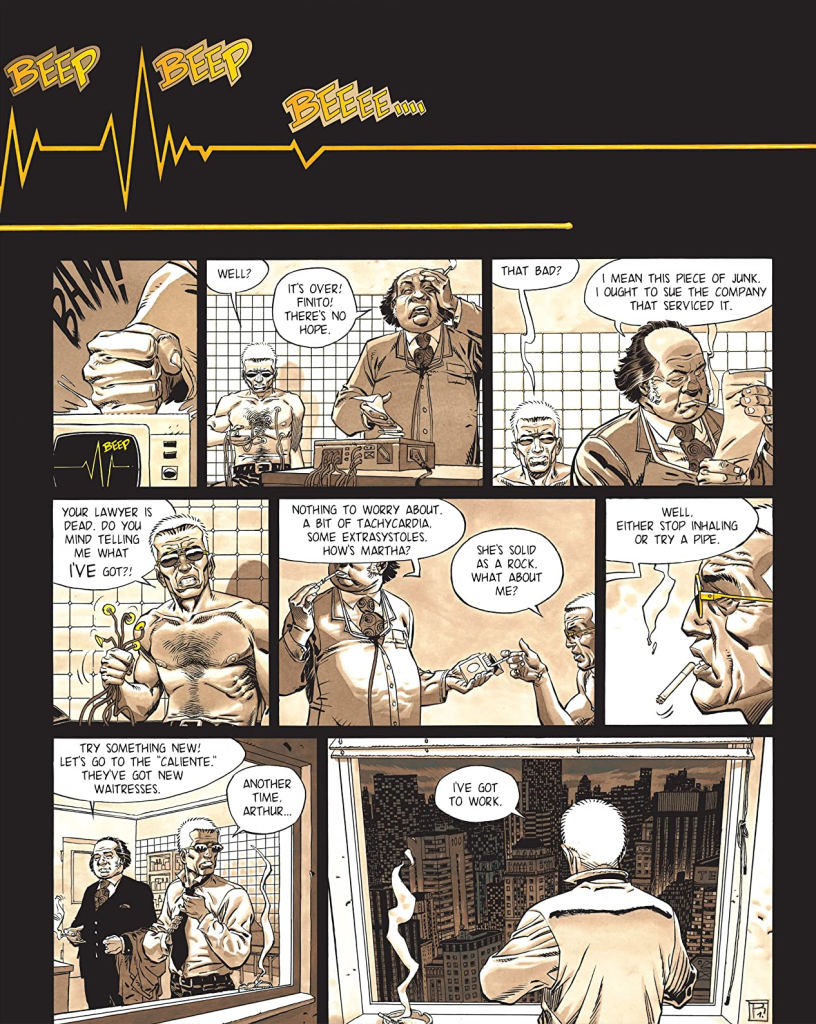

When I ranked my top 50 noir thrillers last month, I only included movies spoken in English. It was an easy way to curb the size of the list. However, this type of gritty, atmospheric crime stories has found an expression in different cultures, inspiring, for example, a ton of Eurocomics.

Lethal Lullaby: Telenko’s Heart

Lethal Lullaby: Telenko’s Heart

With this in mind, I’ve decided that it would also make sense to highlight a dozen foreign-language pictures that I highly recommend for anyone who is into film noir and interested in seeing how this awesome branch of cinema was reinvented throughout the globe, already at the time. Again, I’m sticking to the period from the mid-1940s to the late 1950s, when the world was still picking itself up from WWII and when this genre’s motifs could still be presented with a relatively straight face…

In hindsight, it’s not surprising this narrative and visual form found its way beyond Anglo-Saxon countries. Its elegance was cheap to reproduce even in places without a large-scale film industry and there is something almost universal about many of the themes. Hell, that sort of quasi-transcendence is also what makes noir movies so enduring that we can still enjoy them today (as long as you’re willing to put up with their old-fashioned gender dynamics). In fact, the appeal of trapped anti-heroes desperately trying to escape their situation or character types like the amateur criminal – which lead to stories where we find ourselves rooting for the underdog protagonist to outsmart the professionals, both of the underworld and of the long arm of the law – continue to inform recent works, from Breaking Bad and Ozark to Hannelore Cayre’s best-seller The Godmother.

To be sure, there is something more specific going on in each of the movies listed below. They use tropes like blackmail, backstabbing, cigarette smoke, tough guys, well-delineated silhouettes, and a brooding feeling of existential crisis to explore concrete historical contexts, from occupied Japan to General Franco’s dictatorship in Spain, making them all fascinating objects to discuss and analyze. And while the following list is based more on the noirness of the films’ tones and aesthetics than on their socio-political subtext, naturally there isn’t always a clear-cut distinction between the various layers…

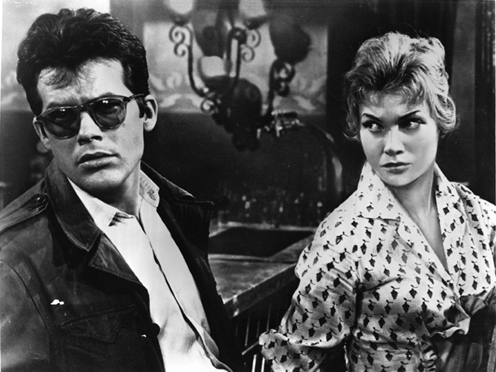

Film noir meets Italian neo-realism and a dozen other influences in this truly original, bewildering, and exciting masterpiece. It’s set in a rice plantation, of all places, where a fugitive hides a stolen diamond necklace and tries to mingle among the seasonal workers, even cynically mobilizing a bunch of illegals to struggle for jobs (thus protecting her cover). Like the story, the visuals mix the ugly reality of harsh working conditions – reflected in many of the faces – with sensationalist titillation, including plenty of curvaceous bodies (most notably the ravishing Silvana Mangano). Indeed, besides the pulpy fun of seeing the typical chases, gunfights, and double-crosses in such an atypical setting, Bitter Rice consistently delivers stirring sound and impressive images through an energetic direction that often goes for extended takes crowded with extras. With its socially conscious charge, you may think of it as a transatlantic relative of Jules Dassin’s Thieves’ Highway (which came out the same year), but this one provides a much more visceral and surprising experience, without the Hollywood polish.

The setting for this one is almost as unlikely: a war-torn Polish town, in the days immediately after the end of WWII, when the Home Army underground resistance was shifting its targets from the Nazis to the Reds. Despite the gloomy weight of war memories, there is an overwhelming sense of coolness to Ashes and Diamonds – not just because lead actor Zbigniew Cybulski appears to be channeling James Dean, but also because Andrzej Wajda’s camerawork keeps swinging around and finding the most potent angles, usually framing the action (or some arresting symbolic element) simultaneously in the foreground and background. Although this is a dark movie (I called Cybulsk the lead, but there are actually a number of subplots woven together, each of them imbued with the genre’s fatalism), it was made in a post-Stalinist context, with the filmmakers clearly having a blast with their commie-killing anti-heroes.

The French loved film noir (hell, they coined the term), but no director went as far in terms of recreating it as Jean-Pierre Melville. Bob le flambeur (‘Bob the high-roller’) opens with an homage to The Naked City (again, by Jules Dassin), but instead of New York we get Paris – and instead of cops and crooks full of piss and vinegar we get aging men, wrapped in weariness and ennui, especially the titular gambler, willing to risk it all in a fateful one-last-job. The result is a sexy, languid, beautiful love letter to American gangster movies and heist thrillers, but also to a certain lineage of French lowlifes. Besides looking back, the film shaped the future of cinema as well, with Melville’s handheld camera shots of Parisian streets inspiring the movement that came be known as Nouvelle Vague. Plus, it boasts one of noir’s niftiest closing lines.

Speaking of Jules Dassin: having been blacklisted in Hollywood, Dassin found a new home in Europe in the 1950s. This is his French – and very bleak – take on heist movies, which became as influential as John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle and Stanley Kubrick’s The Killing. The silent robbery sequence, in particular, is one of the most memorable in this entire subgenre, up there with the one in Dassin’s Topkapi (although, unlike the neat Rififi, the rest of Topkapi is a cheesy comedy that’s practically unwatchable). Many critics see in this story of loyalty and the code of silence an allusion to Dassin’s own experience with HUAC back in the US, but, as pointed out by Ginette Vincendeau in the book European Film Noir, there is a domestic resonance as well, as Rififi’s gangsters ‘may be seen as a covert critique of a generation of men who compromised with the enemy during the war and betrayed the younger generation,’ inscribing the film in a whole cycle of 1950s’ French movies focused on underground societies, torture, imprisonment, and other potential metaphors for the recent Nazi occupation.

A couple of illicit lovers accidentally run over a cyclist with their car and, sure enough, they soon find themselves in a Hitchcockian spiral of tension and paranoia. Like many of the great noirs, the premise of this Spanish thriller is relatively simple, but the increasing suspense, tight editing, sharp dialogue, and moral doubt give it a powerful, mesmerizing allure. Moreover, the film taunts Madrid’s censors with small jabs at the hypocrisy of the ruling class and at the USA’s complicity with the Franco regime. Rob Stone wrote a compelling analysis of the movie in European Film Noir, arguing that, since the protagonist is a product of Francoism, his crisis of masculinity can be read as undermining the hegemony of the regime’s patriarchal pillars, namely the church and the military, ‘both exclusively male organisations which have rendered Francoist Spain in their own likeness.’

6. Elevator to the Gallows (1958)

6. Elevator to the Gallows (1958)

A killer stuck in an elevator. A young couple on the run. A desperate lover. A jazzy soundtrack. The occasional voice-over. Tragic coincidences. A maze-like plot. Neons in the night. A smoke-filled police interrogation. Industrial espionage. And, lingering above all, the ghosts from the colonial wars in Indochina (recently over) and Algeria (still ongoing) haunting French society…

A rookie Homicide cop loses his gun and has to dig deep into Japan‘s broken society to get it back. An early example of Akira Kurosawa’s amazing ability to fuse western cinema traditions with Japanese themes, Stray Dog was shot largely on location, giving us a raw, semi-documentary look into postwar Tokyo (complete with a voice-of-god narration) on top of being a twisty police procedural.

One of the main figures of American film noir, exiled Hungarian actor Peter Lorre, returned to Europe to direct, co-write, and star in this West German psychological drama about Dr Rothe, a doctor at a refugee camp who, upon encountering his former assistant (now a war criminal on the run), has a series of flashbacks about his life as a scientist during wartime, when he became a murderer. A somber mood piece which, according to Tim Bergfelder, ‘invites the viewer to compare and judge different forms of killing alongside each other – Rothe’s ‘private’ homicides; the Nazis’ use of torture and murder; and the random war casualties encountered on battlefields and in bombing raids.’ The movie even uses trains as site and instrument of murder, drawing on one of the ultimate symbols of efficient genocide. That said, along with Vaclav Vich’s expressionistic cinematography, Franz Schroedter’s claustrophobic set designs, and Lorre’s assured direction, it’s the latter’s screen presence that turns The Lost One into such a haunting experience: his spooky eyes, the unsettling voice, the peculiar way he smokes, the blocky shape of his body as he walks, the intertextual echo of Fritz Lang’s M… No wonder he inspired a whole punk jazz concept album.

One of my all-time favorite directors, Henri-Georges Clouzot, did this nasty, lurid French flick about the titular theater performer and her jealous husband, who get caught in a web of murder. At first, you may think the film noir style isn’t particularly pronounced, but soon the high-contrast lighting takes over and, if anything, the themes are even darker than in most entries on this list… The result is a cinematic tour-de-force, nonchalantly suffocating viewers with a tightening knot while taking them on a cold winter journey through the worlds of popular music halls, the pornography business, and seedy police stations, populated to bursting point by captivating, believable characters. In particular, the Maigret-ish Inspector Antoine steals the show as soon as he enters the picture (a veteran from the Foreign Legion, he is yet another reminder of France’s colonial dimension).

More Kurosawa! The story of a difficult relationship between an alcoholic doctor and a young gangster with tuberculosis, set in Tokyo’s slums. Plot-wise, this tragic character study is more of a straightforward drama than the genre-shaped Stray Dog, but Drunken Angel’s overall mood is even more noirish. (Plus, there are more symbolic water puddles here than in Batman: The Killing Joke…)

Kurosawa wasn’t the only one to bring film noir to Japan. I Am Waiting (which also opens with a puddle, perhaps as a nod to Drunken Angel) is a close relative of all those old-school potboilers about doomed lovers, violent memories, and ex-boxers fallen from grace, weaving a stylish, melancholic tale with enough flashbacks, broken dreams, and ironic twists of fate to satisfy any genre fan.

12. Don’t Ever Open That Door (1952)

12. Don’t Ever Open That Door (1952)

An Argentinian adaptation of a couple of unconnected Cornell Woolrich short stories, each of them elegantly shot and acted, with a few melodramatic moments balanced by a very slick pace and mise-en-scène. The first story is a classic noir tale of revenge and vigilante justice, but the second one takes the prize, with a bank robber hiding out at his mother’s place, only to find himself in a proto-Don’t Breathe scenario. The whole thing feels a bit surface-level, but I can’t complain too much… Even the anthology format works out fine, making the movie resemble a live-action South American version of EC’s Crime SuspenStories. (By the way, the shadowy look and cynical edge are so spot-on that I wouldn’t be surprised if comic creators José Muñoz and Carlos Trillo watched this one when they were kids!)