It has become a kind of winter tradition here at the blog to do a post spotlighting cool sci-fi comics about warfare. This started out years ago, as a one-idea post prompted by Rogue One, but there is an endless amount of material worth covering, including a bunch of futuristic weird war tales…

On retrospect, the number of interesting comics is hardly surprising. After all, on the one hand, the genre of science fiction keeps branching in new directions in order to keep up with scientific breakthroughs and the latest sociological concepts. On the other hand, war stories lend themselves to genre mash-ups fairly easily, in part because war produces such a heightened reality that otherwise outrageous, fantastical elements tend to fit right in. Moreover, the tropes of war are so firmly established in readers’ minds that the mere act of twisting or recontextualizing them can be fun.

War/horror mash-ups work particularly well, creating obvious supernatural allegories about the dehumanizing violence of combat and the distorted views of the enemy (John McTiernan’s Predator) or the overwhelming fear of civilians caught in the crossfire (Babak Anvari’s Under the Shadow). Recently, Julius Avery’s Overlord exploited the Nazis’ fixation on – and experimentation with – bodies (although the most outlandish element in the movie was the existence of a non-segregated unit in 1944). In comics, zombies and vampires and the like have shown up in World War II (Red Snow), in Vietnam (‘68), in Afghanistan (Stitched and the underrated Graveyard of Empires), and even in the Guinean liberation war (Os Vampiros).

In the case of science fiction, the appeal is usually to extrapolate about the future of military strategy, with new technology thrown into the mix or devasted landscapes forcing characters to get back to basics. Let’s look at three very different takes on it:

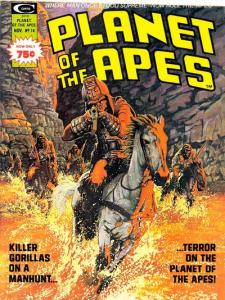

TERROR ON THE PLANET OF THE APES

Planet of the Apes is one of my all-time favorite franchises, even though I’ve conflicted feelings about the fact the it became a franchise at all. My problem is that the original 1968 movie had a perfect ending, one that was powerfully in tune with its Cold War context. It packed a punch precisely because, when those iconic final shots came up, everyone imagined what must’ve happened. The sequels (which, except for the schlocky Beneath the Planet of the Apes, are all prequels) took much of the power away from that ending by detailing what had brilliantly been suggested.

That said, the series has been boldly imaginative and strange, with most entries trying something ambitious: the shocking ending of Beneath, the quirky satire of Escape, the grim dystopia of Conquest… It’s a franchise of fascinating, politically provocative gestures, which is at its best when it blends them with eerie imagery and at its weakest when it provides stunning images without enough substance to back them up (like in the Burton remake as well as in War for the Planet of the Apes, despite the latter’s attempt to achieve transcendence through biblical riffs). I suppose the first installment was so successful that expansion was too damn irresistible, but that doesn’t explain the creativity that followed or the fans’ enduring interest… The core concept of a nightmarish planet where chimps, gorillas, and orangutans dominate humans was strong enough for creators to keep building on it, branching into various (albeit not irreconcilable) timelines. It was memorable enough for pop culture to keep echoing lines like ‘Take your stinking paws off me, you damn dirty ape!’ or ‘Ape shall not kill ape.’ It was appealing enough for suckers like me to keep coming back for more.

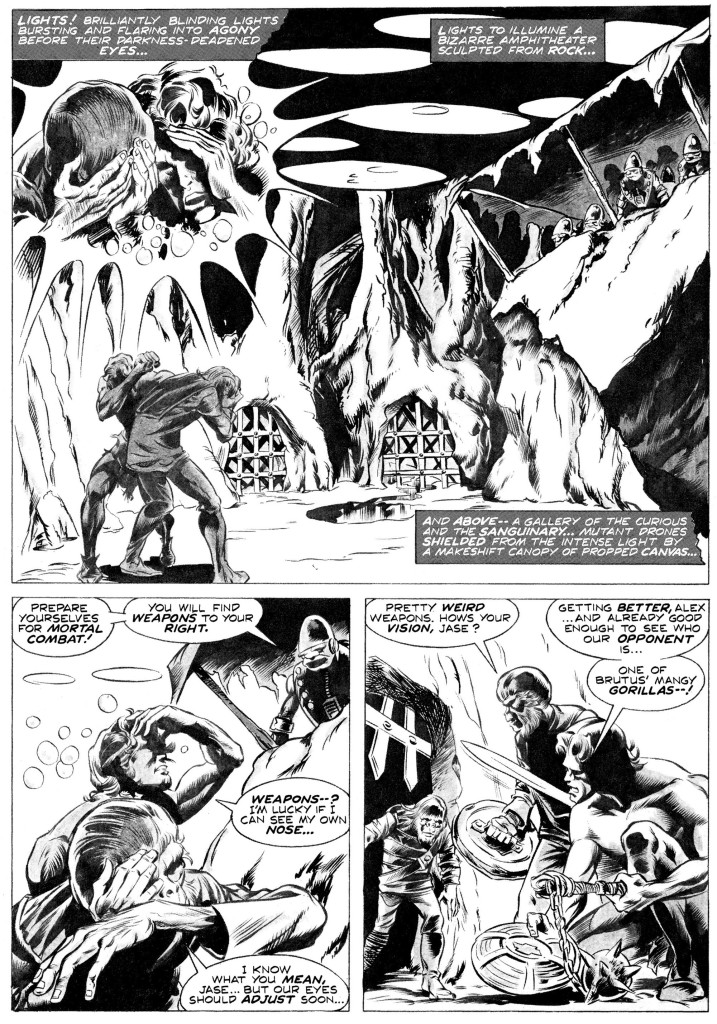

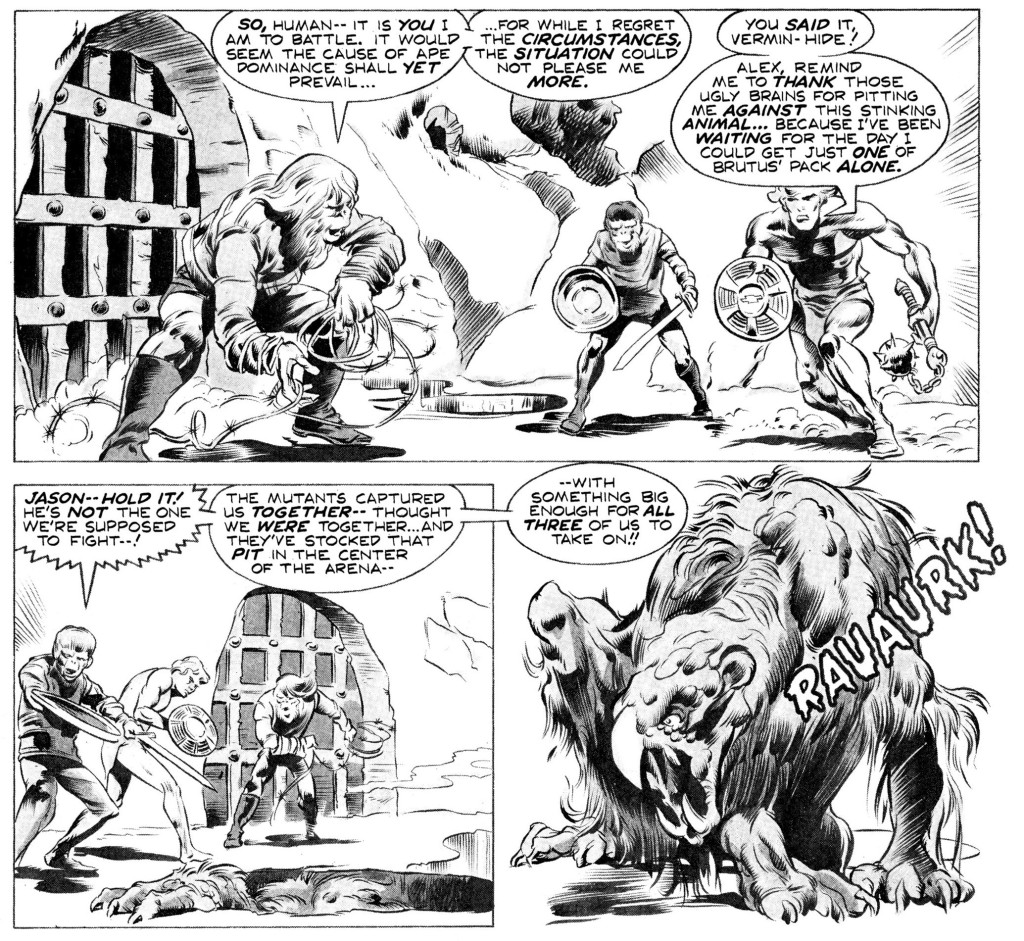

The films’ visionary ideas left quite a mark on comics, both indirectly (from Jack Kirby’s post-apocalyptic Kamandi, the Last Boy on Earth to Keenan Marshall Keller’s and Tom Neely’s trippy exploitation-tribute The Humans) and in the form of official spin-offs. Marvel’s tie-in series – which ran from 1974 to 1979 in one of those lengthy magazine formats, packed with extras about the original movies and TV show – is a great example of what I was talking about: set in an intermediary period when humans and apes still share a civilization, the ongoing storyline ‘Terror on the Planet of the Apes’ further cheapens the original premise by giving us a world that initially feels too familiar, but it still turns out to be highly engaging. After opening with an obvious allegory about racial violence (with the standard twist that white humans are now the vulnerable minority), writer Doug Moench turns the strip into a boys’ adventure saga, with characters constantly running, climbing, and fighting for their lives. Like the films, these comics approach the material with a straight face, never apologizing for the fact that they feature talking chimpanzees and all sorts of mutants. Similarly, Mike Ploog’s moody black & white art keeps things earnest and grounded, even when Moench’s scripts veer into wild territory…

War is all over this storyline. For one thing, there are constant reminders that it’s set after a nuclear holocaust. At one point, Doug Moench describes a valley as ‘splashed in vivid swirls of phosphorescent purple and scarlet… a forest gone mad with the fever of radiation.’ At another level, the first chunk of ‘Terror on the Planet of the Apes’ takes place under the looming shadow of a kind of race war (something that was even more topical in the mid-70s than it is now). Again, it’s not new ground, but, in Moench’s defense, at least he doesn’t pretend like this is an easy issue, as even the heroes have to struggle with their own impulses and prejudices.

The second part of the story is campier, with the protagonists getting stoned out of their minds and a deluded historian regularly bringing humor to the proceedings. It also expands the range of targets by taking potshots at US politics and capitalism (holding an old Bank of America passbook, the historian explains: ‘Now this was absolutely vital to the ancients. It fed God’s emissaries on earth – called computers – and if the computers weren’t fed enough, they’d get sick and report it to their God and things would start to fall apart.’). On the art front, Mike Ploog gives way to Tom Sutton, whose panel borders bend and collapse into engulfing displays of alien technology and madness. By the final stretch, the army of tank-riding gorillas is the least oddball thing around, as we also get winged monkey-demons and brainwashing machines, not to mention the possibility of yet another nuclear Armageddon!

The remaining stories weren’t as entertaining, even if ‘Evolution’s Nightmare!’ (drawn by Ed Hannigan, inked by Jim Mooney) deserves praise as a pacifist parable that revisits the franchise’s Cold War themes. As for the later comics that have gone back to the original continuity, my favorite remains Ty Templeton’s and Joe O’Brien’s Revolution on the Planet of the Apes, which was a smart follow-up to the underrated Conquest of the Planet of the Apes movie (and much cooler than that film’s lame sequel, Battle for the Planet of the Apes).

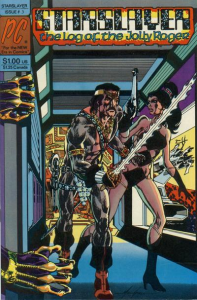

STARSLAYER: THE LOG OF THE JOLLY ROGER

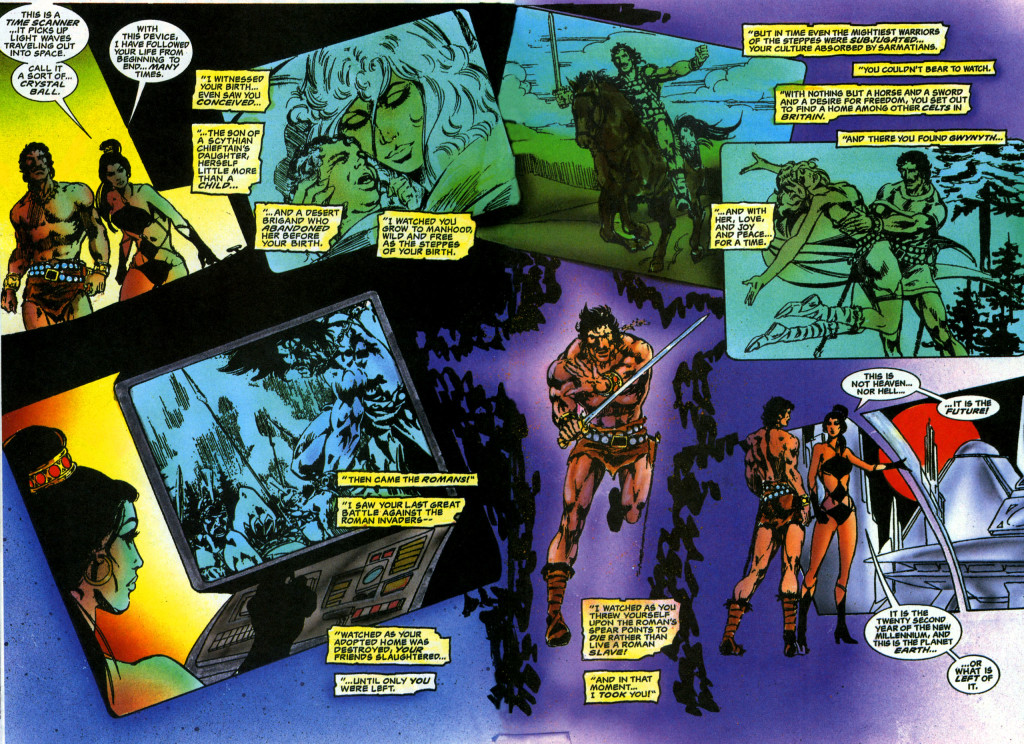

When the damage caused by industrial pollution and out-of-control population growth became irreversible, Earth scientists devised a way to colonize the rest of the solar system by genetically altering settlers so that they could adapt to other planets’ atmospheres. The ensuing confederacy of planets prospered for millennia, but then the sun went nova, engulfing Mercury and Venus while drastically changing the temperatures of the outer colonies… a shift that led settlers to abandon their dying worlds and encroach on the territories of warmer planets, culminating in interplanetary war! This is all just background, though: Starslayer is actually the saga of a Celtic warrior from the Roman era who is brought back from the past to save the cosmos, because the Earth’s Board of Directors is convinced his ‘savage instinct for survival’ may give him an edge in the conflict.

Initially written, illustrated, and lettered by Mike Grell, Starslayer – which started at Pacific Comics in 1982 before moving to First Comics the following year – is a hallmark in the field of indie publishing (not least because its backup features launched fan-favorite series such as Rocketeer and GrimJack). You can plainly see the influence of Conan, Star Wars, John Carter of Mars, pirate swashbucklers, cyberpunk sci-fi, orientalist adventures, and countless two-fisted yarns. Yet Mike Grell proves willing to match all those other works at their game: not only does he take some ballsy narrative turns, but he also raises the level of testosterone, his characters constantly spouting lines like ‘The least you owe a worthy adversary is the chance to die in battle’ or ‘Better to die a free man than to live a Roman slave.’ Moreover, Grell amusingly gives the protagonist a disco look as well as a sidekick robot that talks mostly through lines from Humphrey Bogart movies (playing with yet another ideal of masculinity), plus a spaceship equipped with nautical sails (‘People though it was more… romantic… to take a leisurely cruise of several days, rather than leaping from star to star at warp speed.’).

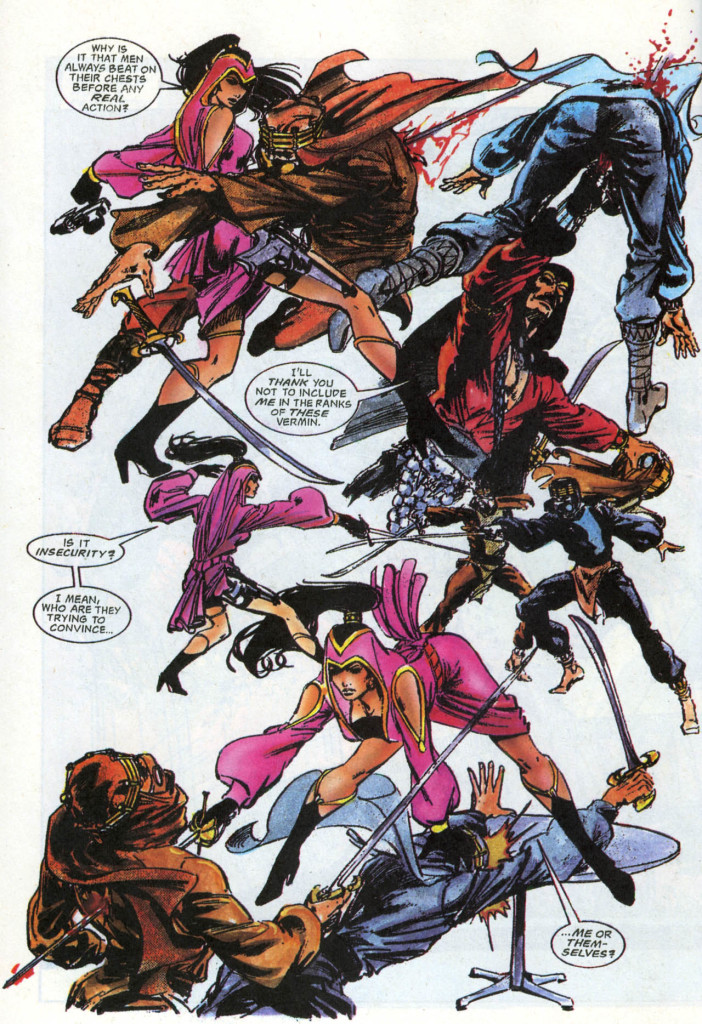

The art is as luscious as you’d expect from Mike Grell. The original colors were by Steve Oliff, but the version I own (a remastered ‘Director’s Cut’ of the first eight issues, published by Acclaim Comics in the mid-90s and recently collected by Dark Horse) is colored by Rob Prior, who tends to go for quasi-psychedelic, not-quite-neon tones. Grell, who can knock out epic splashes and fluidly choreographed action scenes like nobody’s business, feels especially inspired when drawing Starslayer’s badass, statuesque co-star, Tamra:

After Mike Grell wrapped up the interplanetary war plot and left the book, John Ostrander came in as writer with issue #9 and stayed for another couple of years. Edited by the great Mike Gold (the king of eighties’ action comics), Ostrander’s run kept the tone of absurd macho bullshit while adding quirky ideas like the contraband planet Keldomage, which is one vast black market, including its capital city (aptly named Lassay Faire), in whose Bazaar of the Bizarre you can hear loose Monty Python lines. Notably, Starslayer’s heroes travelled to the pan-dimensional city of Cynosure (‘where all possibilities are realized, where dream and reality are indistinguishable, where fact and fantasy play together like children’) and met Grimjack in one of the series’ finest moments.

That said, as much as I love John Ostrander and Tim Truman (who became the regular artist for a while, working with Hilary Barta), their comics never really reached the bravado of Mike Grell’s issues (or of Ostrander’s and Truman’s later space operas in Hawkworld and in the aforementioned GrimJack). Likewise, Lenin Delson’s pencils and Mike Gustovitch’s and Mark Nelson’s inks didn’t match Grell’s raw-yet-elegant style, even if they still delivered dynamic visuals, especially when complemented with Janice Cohen’s stark colors.

All and all, Mike Grell’s Starslayer is a classic whose spirit continues to echo to this day (for example, in Robert Venditti’s and Cary Nord’s run in X-O Manowar).

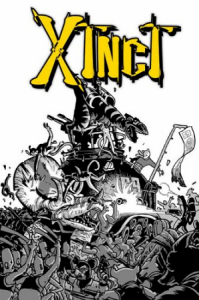

XTNCT

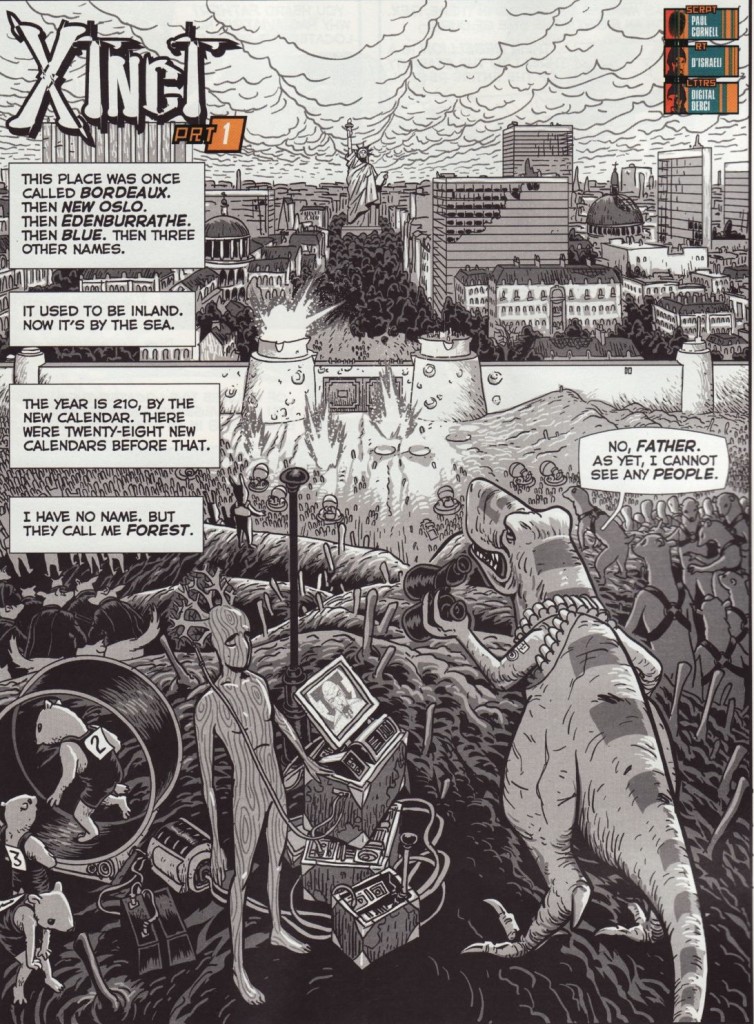

Originally published in the pages of Judge Dredd Megazine in 2003, the awesome short-lived series Xtnct takes place in a war-torn Earth and it follows a rogue commando of genetically modified dinosaurs (and a sentient tree!) chasing down the last few hundred humans on the planet. Yes, it feels like a modern spin on Pat Mill’s misanthropic cult comic Flesh and it sure lives up to that series’ violent, anarchic spirit. Not only that, but D’Israeli makes a kooky concept even kookier through the kind of cartoony, rubbery art and impeccable sense of design he also used in other surrealist sci-fi gems, such as Lazarus Churchyard and Stickleback.

Because it’s written by Paul Cornell, the comic is both funny and somehow smarter than it had any right to be. At one point, the dinosaurs face hipster anti-globalizers obsessed with conspiracy theories about powerful international cabals that sound particularly ludicrous in a world without humans (‘But… there’s only one Jew left in the world.’).

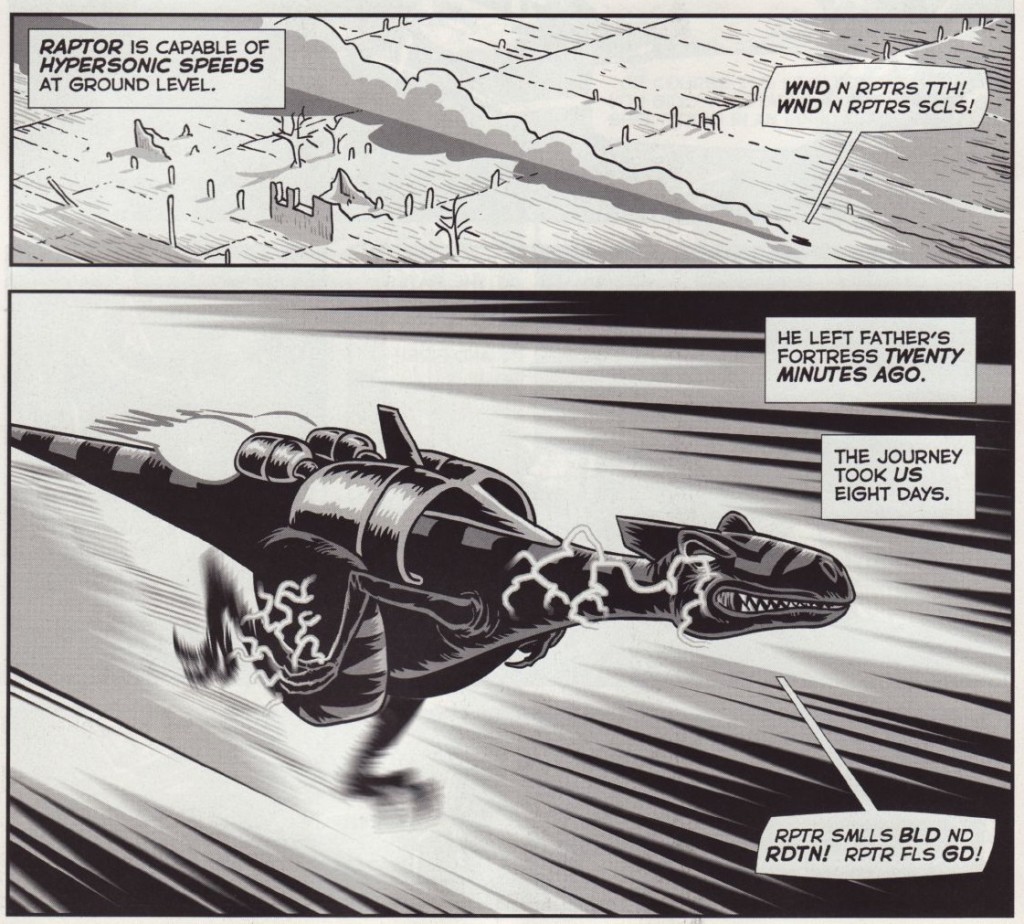

The breakout star is, inarguably, Raptor, a psychotic velociraptor with super-speed who speaks without vowels:

In a clever bit of storytelling, one of the tales is mostly told from the Raptor’s perspective, with everyone’s dialogue hilariously reduced to the basic ways he perceives their reactions (‘Surprised disagreement’; ‘Annoyed mutter.’). And all this takes place before the team causes a chain of atomic strikes, ushering in nuclear winter and spending the rest of the series covered in snow!

The entire run of Xtnct has been collected in the hardcover CM ND HV G F Y THNK YR HRD NGH as well as in the paperback anthology 2000 AD presents Sci-Fi Thrillers.