Writing about The Unknown Soldier last week made me think that I should expand a bit more on the specific genre that is World War II adventure. In fact, I want to go straight to the source and actually talk about the fascinating set of movies that inaugurated this subgenre, made during WWII itself.

It’s easy to see how stories of international intrigue in which globetrotting heroes thwart the plots of Nazis have achieved such an enduring appeal since the war, as they nostalgically evoke a supposedly righteous conflict where Good clearly triumphed over Evil. That said, those narratives often borrow tropes and rhetoric from works that were made in the context of the war itself and, therefore, originally conceived with quite a deliberate agenda. I find the politics of production and the films’ ideological subtext endlessly interesting subjects in their own right (which is why I highly recommend reading Robert L. McLaughing’s and Sally E. Parry’s book We’ll Always Have the Movies: American Cinema during World War II), but what I want to highlight today is the fact that, among all the gung-ho propaganda, many of these original movies managed to be genuinely enjoyable.

Exhibiting a much less respectful approach to WWII than some of the dramas filmed today, they often forgo any sense of realism and tastelessly exploit the conflict for cheap thrills and dramatic stakes. As a result, while some of them have aged poorly (especially the ones with racist depictions of the Japanese), many still hold up as highly gripping and entertaining, especially for fans of pulpy thrillers.

It all goes back to the Brits…

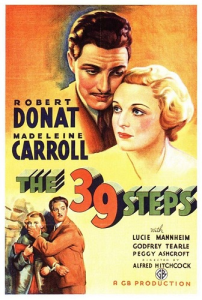

Throughout the 1930s, Alfred Hitchcock had been finessing a type of fast-paced, lighthearted British adventure film built around non-stop cliffhangers and cartoony set pieces – including plenty of dangerous chases – going at least as far back as The 39 Steps and Secret Agent, not to mention the original The Man Who Knew Too Much. That formula reached one of its first peaks with 1938’s The Lady Vanishes, mostly set during a train ride in a fictious Central European country where the ambiguous disappearance of an old lady ended up exposing a convoluted conspiracy. That movie practically kicks off as a comedy, especially because of a couple of caricatural English cricket fans, Charters and Caldicott, but it soon grows into a quirky mystery thriller (with an amusing action scene among a magician’s props and animals) before culminating in an all-out gunfight.

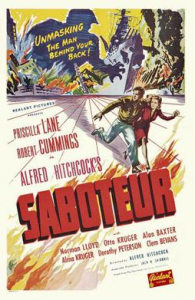

By the time the war started, Hitchcock proved ready to mobilize his skills at mixing tension, humor, and espionage in order to persuade the Americans to join the UK in the fight. In his second Hollywood production, 1940’s Foreign Correspondent, a newspaper sends crime reporter Johnny Jones to pre-war Europe to sniff out what the hell is brewing over there and, sure enough, he comes across a plot against a kind, influential peacemaker (who perhaps served as inspiration for the victim in the Hitchcock-like tale ‘The Third Door,’ from The Batman Adventures #6). Easily one of my favorite Hitchcock flicks, this one has it all: political intrigue, memorable murders, blackmail, witty dialogue, and clever games of cat-and-mouse. Ideologically, it’s a bit of a confused mess – mostly because of the Production Code Authority’s censorship – but as a thriller it contains an impressive array of striking set pieces, especially during the Netherlands sequence (like the shuffling umbrellas or the windmill turning against the wind). A few years later, Hitchcock revisited the war in the goofy home front thriller Saboteur (where rampant symbolism includes both a bearded lady who looks like Lincoln *and* a climax where the protagonist hangs from the Statue of Liberty) and in the brilliant parable Lifeboat (entirely set in a lifeboat in the North Atlantic).

Meanwhile, back in Britain, several filmmakers followed Hitchcock’s lead, addressing the conflict through dynamic films full of elusive MacGuffins and coded messages hidden in songs or cigarette papers… Carol Reed’s Night Train to Munich and, much less memorably, John Baxter’s Crook’s Tour even featured the duo of Charters and Caldicott, once again hazarding their way into comedic spy capers – the former in Germany, the latter in the Middle East. The best British thriller of this era is no doubt 1940’s Contraband, which combines a smart script with incredible sequences in a blacked-out London by the acclaimed writer-director team of Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell (who had honed their craft in this genre with the previous year’s WWI adventure The Spy in Black).

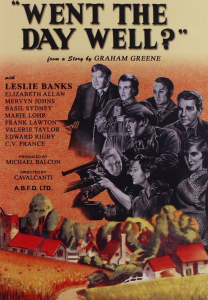

That said, if you’re looking for something a bit sicker, you may get a kick out of 1942’s Went the Day Well?, a delirious piece of propaganda about a Nazi invasion of a small English village – a premise that at the time sounded like a cautionary tale and today like a venture into Alternative History. Based on a Graham Greene story and directed by Alberto Cavalcanti (who also worked on the dark gems Dead of Night and They Made Me a Fugitive), this cult classic may start out like a seemingly harmless, almost ridiculously quaint ideal of bucolic life, but it keeps getting nastier and nastier. I’m positive its twisted depiction of occupation, resistance, and carnage went on to inspire Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds (not to mention John Milius’ Red Dawn).

Alfred Hitchcock wasn’t the only European genius to bring WWII to Hollywood… A master of German expressionism, Fritz Lang also fictionalized the conflict in the form of anti-Nazi suspense. Visually and philosophically, though, Lang displayed a darker sensibility than Hitchcock’s.

In 1941, before the US entered the war, Fritz Lang directed the uneven Man Hunt (which could’ve been the title of most of his films, really), a surreal chase story about a big game hunter caught trying to hunt Adolf Hitler himself back in 1939. He followed it with Hangmen Also Die!, co-written by Bertolt Brecht, about a man hiding in Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia after having assassinated the notorious SS officer Reinhard Heydrich (Brecht’s humanism is a neat, if awkward, match for Lang’s misanthropy). And then there is the mesmerizing Ministry of Fear (another Greene adaptation), a paranoid nightmare set in London during the Blitz, which is shot like gothic horror – including a creepy séance! – yet ends with a punchline about cake.

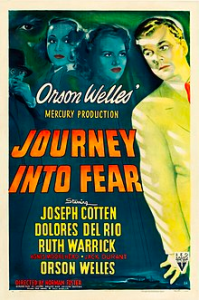

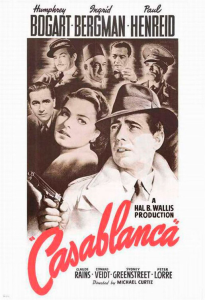

You can see Hitchcock’s and Lang’s blatant influence on a bunch of Hollywood thrillers from this era, most notably in the Turkish adventure Journey into Danger, a loose adaptation of Eric Ambler’s novel, directed by Norman Foster and Orson Welles. However, no movie was more influential than 1942’s Casablanca.

Casablanca’s romantic, proto-noir tale of resistance fighters trying to escape to neutral Lisbon was such a major success that it inspired a string of similar movies (and, later, Batman comics). They are too many to name and not all of them worth your time, but probably the one that went the farthest in terms of trying to emulate Casablanca was 1944’s The Conspirators, by the same producer, cinematographer, and music composer, once again starring Paul Henreid as a resistance leader and the duo of Peter Lorre and Sydney Greenstreet as supporting players. It features a labyrinthic plot set in Lisbon (which makes the movie feel like even more of a follow-up to Casablanca), depicting the city as a hotbed of spies and refugees hanging out in lavish casinos. Although the story is all over the place – and despite whitewashing Portugal’s fascist dictatorship at the time – there are some ultra-moody visuals, courtesy of Jean Negulesco’s direction and Arthur Edeson’s cinematography.

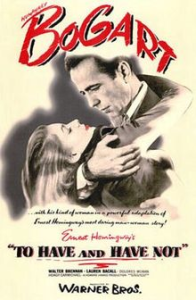

In spite of Lorre’s and Greenstreet’s typically charming performances, what The Conspirators noticeably lacks is Casablanca’s lead, Humphrey Bogart. Bogie’s rugged anti-hero (a cynical tough guy with an idealistic heart who, like America, eventually agrees to join the Allies’ cause) became an archetype for this sort of story. Sure, Bogart had already starred in the WWII adventure Across the Pacific, but that one was a rushed mess (clearly meant to quickly capitalize on The Maltese Falcon’s success), so it was Casablanca that really popularized his screen persona. That persona was then firmly cemented by Howard Hawks’ To Have and Have Not, where Bogie played virtually the same character arc, albeit this time around set in Martinique and with plenty of memorable flirting with a smoldering Lauren Bacall. It’s also a looser film than Casablanca, less about the plot than about the way the cast interacts, with the kind of moody scenes Hawks loved, where characters bonded over music (the same device he used, to great effect, in Only Angels Have Wings and Rio Bravo), including a nice rendition of ‘Am I Blue’ (although not as nice as the Caped Crusader’s).

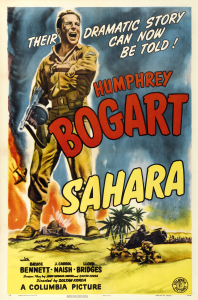

As for other Humphrey Bogart vehicles, I’m not the biggest fan of Passage to Marseille (where he plays a French gunner, reuniting with Casablanca’s director Michael Curtiz and much of that film’s cast), whose blatant promotion of French nationalism is too in-your-face, taking over the story. I much prefer Action in the North Atlantic – which follows a dangerous mission of the US Merchant Marine – because at least there the propaganda is woven into the narrative in clever and sometimes amusing ways. My favorite, though, is the gritty Sahara, where Bogie plays a tank commander in Libya, desperately fighting against Erwin Rommel’s Afrika Corps in the middle of the desert.

Sahara is the kind of military thriller that also works for fans of violent adventure (especially if you don’t stop to seriously consider the fact that it’s depicting violence that was actually taking place at the time). Another one I would put on that list is John Farrow’s China, starring an Indiana Jones-looking Alan Ladd trying to drive to Shanghai among Japanese attacks with his partner – the dependable William Bendix – and an orphaned baby boy.

If you want espionage to go with your two-fisted adventure, my main recommendation is Billy Wilder’s Five Graves to Cairo, about a soldier who stumbles into an isolated hotel in the middle of the North African desert, where Rommel sets up the temporary headquarters for a secret operation. Written by the power duo of Wilder and Charles Brackett, this one awesomely displays their flair for both sardonic wit and ingenious storytelling that relies on viewers’ ability to join the dots. Raoul Walsh’s Northern Pursuit is also worth checking out, if nothing else for the chance to watch Errol Flynn play a kickass Canadian Mountie!

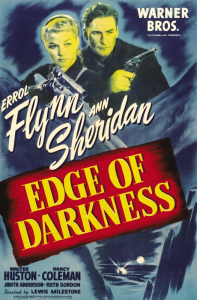

Although Flynn has become better known for his alleged fascist sympathies (spoofed in Howard Chaykin’s Blackhawk: Blood & Iron and in The Rocketeer movie), he also starred in one of the strongest anti-Nazi resistance thrillers of this era: Edge of Darkness, set in an occupied Norwegian village. It’s a pretty grim slice of propaganda, but also really well-crafted – for instance, I love how the secret meetings between Resistance members keep finding new ways to highlight their democratic values, contrasting them with the occupiers.

Resistance in Nazi Europe was the subject of several other productions, from Ernst Lubitsch’s hilarious screwball comedy To Be or Not to Be to Jean Renoir’s sentimental political drama This Land is Mine. There was even a sort of remake of the 1932 classic Grand Hotel, now reimagined as Hotel Berlin.

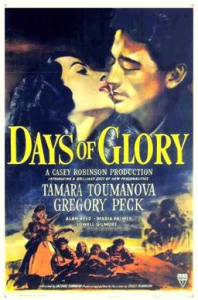

Believe it or not, one of Hollywood’s coolest Resistance thrillers, Days of Glory, actually focuses on Soviet guerrillas. It was directed by the great Jacques Tourneur, who sure knew how to turn a B-movie into a remarkable showcase of haunting imagery and nail-biting suspense. The emphasis on solidarity, culture, and sacrifice for the collective, although common to other war films, fits in particularly well with the heroes’ communist background.

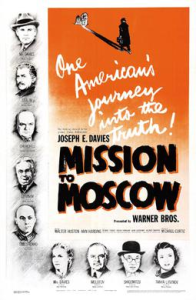

During the Grand Alliance that brought together the US, the UK, and the USSR, Hollywood churned out a bunch of other movies with a positive message about their Soviet allies, but they tend to be more fascinating as historical documents than as straightforward entertainment – not that there isn’t a sort of campy entertainment value in watching 1943’s The North Star, which starts out as an ultra-cheerful musical about the wonders of life in a Soviet collective farm before morphing into one of the most viciously violent war epics you’ll ever see (to the sound of ‘The Internationale’). Or 1944’s Song of Russia, a perversely endearing bit of hokum about a romance between an American conductor and a Russian pianist (which features an unforgettable scene where girl-next-door Susan Peters teaches children how to make Molotov cocktails). And don’t even get me started on Mission to Moscow, directed by Michael Curtiz as full-on Stalinist propaganda, complete with long sequences justifying the purges and Moscow’s pact with the Nazis! (Hey, at least the result is funnier than Police Academy: Mission to Moscow…)

Except for Casablanca, I don’t think World War II adventure films are as fondly remembered as they should be. Still, they did retain a small presence in subsequent popular culture. Most notably, 1984’s absurdist comedy Top Secret! – about Elvis Presley getting entangled in foreign intrigue during a trip to East Germany – spoofed several of this subgenre’s narrative and visual tropes (and a bunch of specific scenes from The Conspirators), mixing them with references to Presley’s musicals and The Blue Lagoon, not to mention a fair amount of fake poo and erection jokes.

To be sure, this surrealist masterpiece derives most of its gags from playing with cinematic language in general (constantly subverting typical shots, sounds, and editing in unexpected ways), including a remarkable scene at a Swedish bookshop shot backwards (because everyone knows backwards English sounds just like Swedish!). Yet there is an additional meta element that arises precisely from the fact that Top Secret! is tapping into this genre while amalgamating WWII and the Cold War (not only do the East Germans dress like Nazis, at one point Elvis joins the French Resistance… in the GDR!). The result places Hollywood propaganda in a continuum, ultimately mocking its long tradition of caricatural approaches to international politics, but also paying homage to the industry’s willingness to throw good taste and logic out the window in the name of thrilling fun.